Abstract

Cigarette smoking has been associated with both the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and a vaginal microbiota lacking protective Lactobacillus spp. As the mechanism linking smoking with vaginal microbiota and BV is unclear, we sought to compare the vaginal metabolomes of smokers and non-smokers (17 smokers/19 non-smokers). Metabolomic profiles were determined by gas and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry in a cross-sectional study. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene populations revealed samples clustered into three community state types (CSTs) ---- CST-I (L. crispatus-dominated), CST-III (L. iners-dominated) or CST-IV (low-Lactobacillus). We identified 607 metabolites, including 12 that differed significantly (q-value < 0.05) between smokers and non-smokers. Nicotine, and the breakdown metabolites cotinine and hydroxycotinine were substantially higher in smokers, as expected. Among women categorized to CST-IV, biogenic amines, including agmatine, cadaverine, putrescine, tryptamine and tyramine were substantially higher in smokers, while dipeptides were lower in smokers. These biogenic amines are known to affect the virulence of infective pathogens and contribute to vaginal malodor. Our data suggest that cigarette smoking is associated with differences in important vaginal metabolites, and women who smoke, and particularly women who are also depauperate for Lactobacillus spp., may have increased susceptibilities to urogenital infections and increased malodor.

Introduction

According to the U.S. National Health Interview Survey, 13.9 percent of U.S. women reported that they smoked cigarettes in 20161, and it has been well-documented that women who smoke have greater risks for adverse reproductive health outcomes, including premature birth, delivery of low birth weight infants, certain birth defects, and ectopic pregnancy2–6. Smokers are also more susceptible to bacterial infections than non-smokers7, however, few studies have investigated the mechanisms linking smoking and gynecologic infections. Smoking has been shown in large observational studies to be a dose-dependent risk factor for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV)8–13, as well as significantly associated with risk of other genital infections in females including Trichomonas vaginalis14, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)15 and Chlamydia trachomatis16,17. Smoking has long been implicated in higher risk for oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence and viral load, progression to cervical pre-cancer, and vulval intraepithelial neoplasia18–23. Smoking is associated with damaged cervical epithelium through DNA modification and suppressed local and systemic immune responses24, both of which may increase susceptibility to a wide range of female reproductive tract infections25,26. Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been shown to become concentrated in cervical mucus, providing evidence that smoking can directly affect the vaginal and cervical epithelium27,28. Smoking cessation was also associated with dramatic changes in the gut microbiota in one study29.

In a 2014 study, our research group confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is strongly associated with smoking30. In that study, we compared the vaginal microbiota, as determined by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, between smokers and non-smokers. We reported that women who had a vaginal microbiota that were lacking significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp. were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than women with a L. crispatus-dominated microbiota. Most Lactobacillus spp. are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections through the production of lactic acid and bacteriocins31,32. The lactic acid reduces the vaginal pH to ≤4.0 and is a potent bactericide and virucide31,33–36. Indeed, epidemiologic studies have shown that a relatively low level of Lactobacillus spp. and the presence of a wide array of strict and facultative anaerobes in the vaginal microbiota, as observed in the clinical diagnosis of BV, is associated with increased incidence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)15,37–43.

Despite advances in understanding the epidemiologic links between smoking and women’s reproductive health, the mechanistic processes by which smoking affects the vaginal microenvironment and BV is unclear. The effect of smoking on the function of the microbiome can be investigated by assessing the metabolome. The metabolome is the set of small (<1 kDa) molecule chemicals, which includes host and microbially-produced and modified biomolecules, as well as exogenous chemicals44. Measurement of the metabolomic profile from any biological sample is expected to contain numerous low molecular mass molecules with different physicochemical characteristics and concentration ranges44.

The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment and differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota45–48. For example, the presence of certain chemicals or metabolites have been shown in vitro to directly reduce or inhibit the growth of select bacterial species49–51. Biosynthesis of biogenic amines (BAs) (cadaverine, putrescine, spermine, spermidine, trimethylamine, and tyramine) may allow various bacteria to survive in low pH environments52, like that found in the healthy Lactobacillus-dominated vagina. BAs have also been shown to enhance growth rates of various pathogenic bacteria, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and shield them from host innate immunological defenses53–55. The recent applications of metabolomics with in vivo samples have identified relationships between bacterial species and vaginal metabolomic profiles. In particular Dialister, Mobiluncus, Atopobium, Prevotella, Mycoplasma and Gardnerella species were correlated with the presence of several metabolites along with vaginal odor and discharge45–48. We have hypothesized that BAs may be an important feature in the destabilization of Lactobacillus spp.-dominant vaginal microbiota and the initiation of BV, as well as the characteristic malodor of BV56. The decarboxylation of amino acid precursors to form BAs results in increased pH and may increase the risk for BV57.

In this study, we sought to characterize vaginal microbiota functional differences between smokers and non-smokers by investigating the vaginal metabolome. These data may allow enhanced understanding of the mechanism by which smoking may increase the risk of urogenital infections and may contribute to our understanding of the effect of smoking on the female reproductive tract.

Results

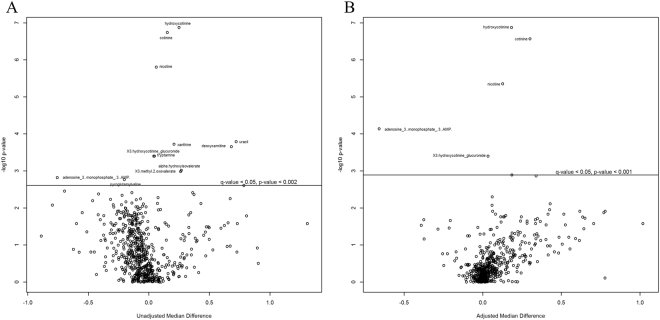

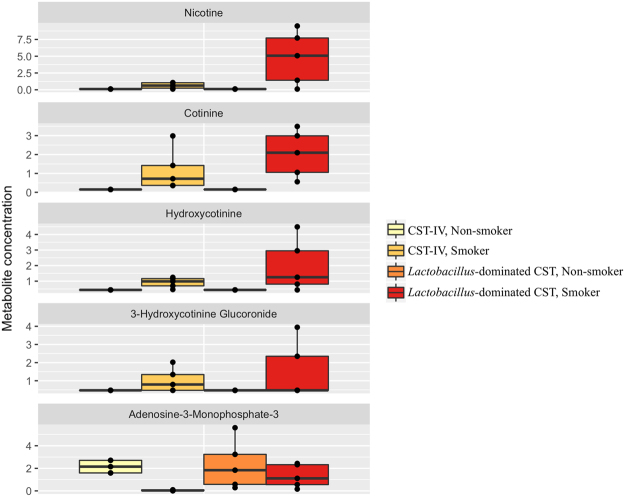

In total, 607 compounds were identified in the vaginal metabolome of 36 women. PCA indicated that the metabolomic profiles clustered by both smoking status and bacterial community state type (CST) (Figure S1). CST accounted for 23% of the metabolite variation observed in the complete data set (distance based linear model, DISTLM F = 9.9397, PPERM = 0.0001; Table 1), while smoking status explained 6%. However, the concentrations of 12 metabolites were significantly different between smokers and non-smokers (q-value = <0.05; Fig. 1A, Table S1). Tobacco constituents and their primary breakdown products (nicotine, cotinine and hydroxycotinine) represented the strongest differences between smokers and non-smokers with non-smokers having a 2- to 12-fold reduction in these compounds (q-value = <0.05). After adjusting for the influence of CST, five of the metabolites persisted in their differences between smokers and non-smokers (Figs 1B, 2).

Table 1.

Significantly fitted predicator variables to vaginal metabolites.

| Variable | SS (trace) | Pseudo-F | p-value | Proportion (%) | Cumulative Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual model test | |||||

| CST | 3181.00 | 9.94 | 0.002 | 22.62 | NA |

| Smoking status | 880.65 | 2.27 | 0.074 | 6.26 | NA |

| Race | 1120.00 | 2.94 | 0.033 | 7.96 | NA |

| Education level | 1216.90 | 3.22 | 0.038 | 8.65 | NA |

| Fitted model with selected variables, adjusted R2 = 0.26 | |||||

| CST | 3181.00 | 9.94 | 0.001 | 22.62 | 22.62 |

| Race | 817.71 | 2.68 | 0.037 | 5.82 | 28.44 |

| Education level | 533.18 | 1.79 | 0.11 | 3.79 | 32.23 |

| Smoking status | 292.20 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 2.08 | 34.31 |

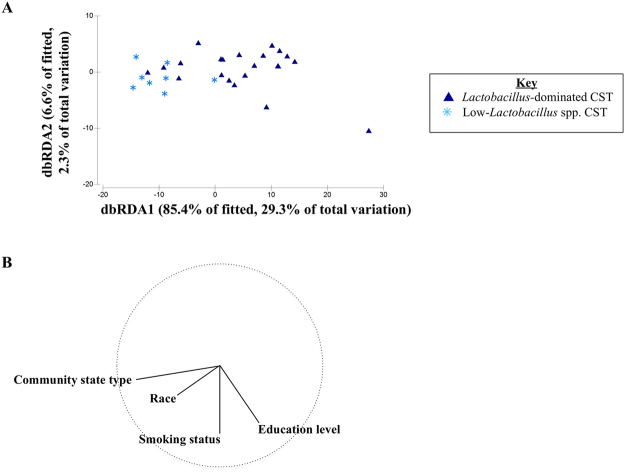

Distance based linear modelling (DISTLM) was performed on vaginal metabolites fitted with participant behavioral variables listed in Table 2. DISTLM was conducted with adjusted R2 over 9,999 permutations. DISTLM identifies the best-fit model based on all the available variables that best-explain the composition of vaginal metabolites. The visual display of these data as represented by the distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) plot is displayed in Fig. 3.

Figure 1.

Compounds differing between smokers and non-smokers with and without adjustment for CST. Volcano plots display –log10 (p-value) and the median difference in concentration between smokers and non-smokers when unadjusted (A) and adjusted for community state type (B). Quantile regression was conducted on centered and scaled metabolite concentrations. Significance testing was conducted with Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected for multiple comparisons. Metabolites that differed significantly where q-value < = 0.05 between smokers and non-smokers are shown above the line in each plot.

Figure 2.

Vaginal metabolites that differ between smokers and non-smokers. Boxplots display metabolites identified as significantly (q-value = <0.05) different in the vagina of smokers and non-smokers when unadjusted and adjusted for the impact of bacterial community state type (CST). Samples categorized as CST-I (L. crispatus-dominated) and CST-III (L. iners-dominated) were grouped and compared with CST-IV (low-Lactobacillus spp.). Quantile regression was conducted on centered and scaled metabolite concentrations. Significance testing was conducted with Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected for multiple comparisons.

Further, 142 metabolites had abundances that were marginally significantly different between smokers and non-smokers (q-value between 0.05 and 0.10) without adjustment for CST (Table S2). These compounds are involved in amino acid metabolism, including some essential for bodily functions such as lysine, tryptophan, leucine, isoleucine, histidine and methionine as well as many amino acid dipeptides required for protein hydrolysis. Interestingly, the greatest differences in the composition and abundance of the metabolomes between smokers and non-smokers were among biogenic amines, including, cadaverine (fold change in non-smokers, FC = −53.19), putrescine (FC = −15.80), agmatine (FC = −15.49), tyramine (FC = −5.15) and tryptamine (FC = −4.43), which were much higher in smokers (Table S2, Figure S2).

The associations observed between smoking and the vaginal metabolome may be explained in part by participant-specific variables, such as sexual behaviors, health, race and other confounding factors. We utilized a distance-based linear modeling (DISTLM) approach to explain the contribution of confounding participant variables to the vaginal metabolome (Table 1). Due to the relatively small sample size of our study, the model was limited to a total of four variables, which we selected as the best fit from all potential models with the inclusion of smoking status and CST. The model including CST, race, education level, and smoking status, had an adjustedR2 of 0.26, and these variables explained 34% of the observed variation in the vaginal metabolomic profiles (Table 1). Using this analytical approach based on the full metabolome, smoking status did not show a statistically significant relationship to the full spectrum of vaginal metabolites after adjustment for CST, race, and education, although in some cases, when the associations are large and the p-values do not reach significance, it may be due to the lack of power associated with the relatively small sample size (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Participant predictor variables fitted to vaginal metabolites. Distance-based linear modelling (DISTLM) was conducted on log-transformed Euclidean distance matrix of vaginal metabolites. All variables were included in the final model that when applied to the data cloud of vaginal metabolites (Table 1). Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) plot (A) displays the metabolite composition fitted to the four variables labeled with the strongest variable, CST. Variable vectors indicating strength and direction are identified (B).

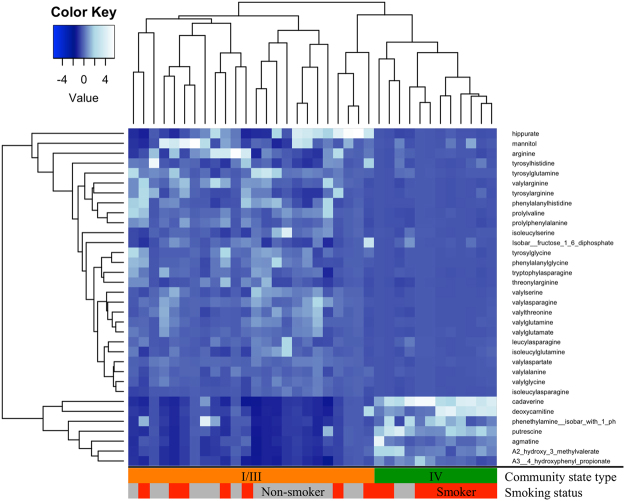

In addition to the multivariate analyses above, we also sought to directly contrast the metabolome of Lactobacillus-dominated CST-I/III and the low-Lactobacillus/diverse anaerobes observed in CST-IV. To increase the power of significance testing, we combined L. crispatus-dominated CST-I and L. iners-dominated CST-III. In bivariate analysis, there was a significant difference (q-value < = 0.05) in the concentrations of 67% of all identified vaginal metabolites between CST-I/III and CST-IV (Table S3). After adjusting for the influence of a woman being a current smoker, the abundance of 54% of vaginal metabolites still differed significantly (q-value < = 0.05). The majority of the metabolites that were elevated in the Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs were amino acids, lipids, peptides and especially dipeptides (Fig. 4). Carbohydrates, mannitol, lactate, xylulose and fucose were higher in the Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs compared to CST-IV (Table S3). The glycine conjugate of benzoic acid, hippurate, was also markedly higher (34-fold) in Lactobacillus-dominated communities. The BAs (cadaverine, putrescine, agmatine, tyramine, tryptamine) and the straight chain fatty acid deoxycarnitine were also observed to be significantly higher in CST-IV compared to Lactobacillus-dominant communities (Table S3). Correlations with pH measurement and BA concentrations were positive, yet lacked statistical significance (Table S4, Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Metabolites differ between CST. Heatmap displays selection of metabolites with a high fold change identified as significantly (q-value = <0.05) different in the vagina of bacterial community state type (CST) when unadjusted and adjusted for the impact of smoking status. Low-Lactobacillus CST-IV and Lactobacillus-dominated CST-I and CST-III are grouped. Quantile regression was conducted on centered and scaled metabolite concentrations. Significance testing was conducted with Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected for multiple comparisons.

Further, among women in CST-IV, the BAs were markedly higher in smokers versus non-smokers (q-value: <0.05, Cadaverine (89-fold), Putrescine (26-fold), Agamatine (26-fold), Tyramine (10-fold) and Trypatamine (7-fold), Figure S2).

Discussion

Our group and others have previously reported that female smokers are more likely to display a low-Lactobacillus CST-IV vaginal microbiota and are at increased risk for morbidities such as bacterial vaginosis9,30 and sexually transmitted infections39. To obtain greater insight into this relationship, we assessed the vaginal metabolome of smokers and non-smokers. Using a comprehensive metabolomics approach and multiple analyses of the data, we identified an extensive and diverse range of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. Bacterial composition (CST) was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome in our model and was associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites, suggesting vaginal microbiota are the major drivers of the vaginal metabolome. We therefore carefully controlled for CST in multivariate analysis and also conducted stratified analysis based on CST so that we could directly contrast smokers versus non-smokers, while essentially holding CST constant. As expected, nicotine and its breakdown products were markedly elevated in the vagina of smokers. In humans, 70–80% of nicotine is converted to cotinine followed by conversion to hydroxycotinine58. Hydroxycotinine is a well-known biomarker identified in the urine, plasma and serum of individuals exposed to both active and passive smoking59–61. Previous studies have identified nicotine and cotinine in the cervical mucus of smokers27 with good correlation to concentrations in blood and urine62,63. Our findings are consistent with the vaginal metabolome contributing to the mechanism linking smoking to the microbiome.

Another key finding was that we observed significant increases in the abundance of various BAs among smokers relative to non-smokers, which was far more pronounced in women with a low-Lactobacillus CST-IV. BAs are unique molecules that carry one or more amine groups (NH2). They are essential to mammalian and bacterial physiology, tightly controlled in cellular metabolisms. Cadaverine, putrescine, agmatine and tryptamine have roles in the metabolism of essential amino acids, including tryptophan and lysine. Their accumulation indicates upheaval or alterations in these metabolic systems. In particular, the odors of the amines cadaverine and putrescine are foul-smelling to humans, identifiable as indicators of tissue decomposition associated with death or bacterial contamination64,65. Several of these BAs, including cadaverine and putrescine, have previously been correlated with diagnosis of BV45,66,67 and implicated in the associated ‘fishy’ vaginal malodor of BV46,47.

Our group recently suggested a hypothetical model for the displacement of vaginal Lactobacillus spp. and increased risk of BV and urogenital infection with BAs68. We hypothesize that in the vaginal canal, BAs may favor non-Lactobacillus species, while also increasing the vaginal pH, collectively enabling colonization by a more diverse community, as is observed with CST-IV. Our hypothesis is based on two observations. First, the amino-acid decarboxylation reactions that produce BAs involve the consumption of intracellular hydrogen ions and is a well-described bacterial acid resistance and mitigation mechanism52. The consumption of hydrogen ions increases the pH of the local habitat52, overcoming what is widely considered the primary barrier to pathogen outgrowth and a clinically-recognized symptom of BV. Second, the growth of several pathogens, including the urogenital pathogen, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and their resistance to host immunological defenses has been shown to be superior in the presence of various BAs53–55,69. In this study, we observed that lactate was lower and BAs were higher, in low-Lactobacillus CST-IV participants as expected. However, lactate was higher in Lactobacillus-dominated CST-I/III even when BA concentrations were low. Lactate concentration includes both protonated lactic acid (LAH) and lactate anion (LA−) with the former being recognized as the active microbicidal form capable of inactivating BV-associated bacteria31,70. Lactate concentrations increase with increasing hydrogen ion concentrations31 and therefore the reduction in lactate and increase in BAs further supports our hypotheses, and suggest that bacteria present in low-Lactobacillus CST-IV use available hydrogen ions to perform amino acid decarboxylation and produce BAs, thus resisting acid stress56.

Our results identifying the presence of nicotine breakdown products in smokers may reflect differences in the degree of transport and/or accumulation of nicotine and its derivatives in the vagina by CST. These differences may relate to the co-variation in pH with CST33. Absorption of nicotine across biological membranes (such as cervicovaginal endothelial/epithelial cells) has previously been shown to be pH dependent56,71. Nicotine is a weak base (pKa = 8.0) and in acidic environments nicotine does not rapidly cross membranes68. Cotinine and hydroxycotinine are more acidic with a pKa = 4.8 and 4.3, respectively72. Previous studies which have measured both in serum and vaginal samples identified higher levels of nicotine in the cervical mucus compared with serum samples, yet cotinine values were similar27,63. Nicotine may be selectively concentrated in the vagina because the majority (72%) of women display a vaginal pH of 4.0 to 4.633. Conversely, women with low-Lactobacillus CST-IV vaginal microbiota have a vaginal pH of 5.3 ± 0.633 and, consistently displayed comparatively lower levels of nicotine. Alternatively, these findings may indicate microbiological metabolism of nicotine in the more diverse and low-Lactobacillus state of CST-IV.

Similarly, hippurate, a normal excretory product of urine that is increased with exposure to phenolic compounds and toluene, a byproduct of cigarette smoke73, was increased in Lactobacillus-dominated CST-I/III over CST-IV and also in non-smokers over smokers. Hippurate is a known substrate of Gardnerella vaginalis74, an organism often found in higher abundances when Lactobacillus spp. are low and commonly associated with symptomatic BV75–77. Hippurate is decreased in the low-Lactobacillus CST-IV and this may suggest that microbial utilization of hippurate and therefore smoking may move the vaginal environment closer to favor the proliferation of G. vaginalis.

Beyond metabolites directly affiliated with nicotine metabolism, we observed substantive shifts in dipeptides and biogenic amines. More than 150 dipeptides in smokers or CST-IV participants were significantly decreased relative to non-smokers and those with Lactobacillus spp.-dominated vaginal microbiota. In a previous study, Ghartey and colleagues noted significant reductions in vaginal dipeptides among women who delivered infants preterm, for which CST-IV and BV are important risk factors78. Dipeptides refer to one or more amino acid joined by a peptide bond with important roles in protein metabolism and cell signaling. CST-I and III women had higher concentrations of dipeptides relative to CST-IV, suggesting Lactobacillus spp. dominance may be important to this phenotype. Dipeptides are constituents of the peptidoglycan cell wall of bacteria and are made during its’ synthesis. Therefore, some dipeptides, such as muramyl dipeptides, serve as signal to the immune system in mammals and play a direct role in the regulation of inflammation79. Their production has also been indicated in Lactobacillus spp. and other bacteria as a mean of quorum sensing and cellular signaling80. Lactobacillus spp. may exploit dipeptides to increase their osmotolerance81, or produce dipeptides for amensalistic purposes. Various Lactobacillus spp. have been noted to produce cyclic dipeptides with anti-fungal80,82–84, anti-viral85 and anti-bacterial80,86 properties. This includes the production of dipeptides by a vaginal isolate of L. reuteri that disrupts the virulence capabilities of Staphylococcus aureus involved in toxic shock syndrome67. The increase in dipeptides in non-smokers and Lactobacillus spp.-dominant CSTs may be reflective of increased production by Lactobacillus spp. of these bioactive compounds. Conversely, the reduction in dipeptides in women with a low-Lactobacillus CST-IV vaginal microbiota may be a result of the increased proteolytic activity from bacteria present in this CST. Many BV-associated bacteria have been correlated with, or shown to be capable of secreting proteases, which break down proteins into amino acids87–91. Aside from reducing the number of detected dipeptides in the vaginal tract, proteases may also have the effect of inactivating proteins important to host defenses and make host tissues more susceptible to other organsims’ virulence factors87.

The breakdown compounds of a number of drugs, such as cocaine (norbenzoylecgonine, benzoylecogonine), antidepressants (escitalopram), common painkillers (acetaminophen glucoronide, ibuprofen) and decongestants (pseudoephedrine) were each observed in one or more samples in the study. This indicates that some drugs could possibly be assessed from vaginal metabolomic profiles. There is relatively little known about the relationship between individual drugs and their impact on the vaginal microbiome. Cocaine use has been associated with shifts in bacterial phyla in the gut92 and additionally has been associated with a greater likelihood of contracting sexually transmitted infections93,94. The use of antidepressants has been linked to menstrual disorders and hormonal changes in women95,96 both of which may cause indirect shifts in the vaginal microbiota. As these studies may suggest a potential impact of drugs and medications and their byproducts on the vaginal microbiota, further exploration is needed to make any conclusions.

Our data are consistent with recent studies of the vaginal metabolome45,47,97. In prior studies, the BAs (cadaverine, putrescine and tyramine) were consistently higher in women with BV45,47,48,97. We did not detect trimethlyamine in our samples as has previously been identified and we suspect this is due to its high volatility45,47,48,97. Srinivasan et al. reported the same issue with their lack of trimethylamine detection using similar methods yet reported lower levels of trimethylamine oxide (an intermediary product) in women with BV using separate methods97. Therefore, there are limitations to the use of metabolomics, including particle resolution, compound sensitivity, polarity and volatility98. Identification of detected metabolites is further constrained by comparison to facility-built databases98,99. However, this is best achieved by utilizing standardized collection, preparation and98 pairing liquid chromatography (LC), gas chromatography (GC) and mass spectrometry (MS) which can enhance identification of analytes with differing characteristics98.

Aside from biogenic amines, McMillian et al. reported alpha-hydroxyisovalerate and gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) as associated with BV and high bacterial diversity47. We also observed higher levels of alpha-hydroxyisovalerate and GHB in low-Lactobacillus CST-IV and additionally we observed a trend towards increases in smokers. Alpha-hydroxyisovalerate was positively correlated with diverse BV-associated bacteria such as Atopobium, G. vaginalis, Dialister and Gemella. McMillian et al. went on to show how G. vaginalis, a vaginal bacterial species commonly associated with BV is a producer of GHB47. Srinivasan et al. also identified 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) in cases of BV and we also detected a significantly high abundance of this compound in women from CST-IV over the Lactobacillus-dominant CSTs (I or III), although it was not associated with smoking status97.

A limitation of our study was the small sample size and the distribution of smokers and non-smokers within each community state type (17 CST-I, 7 CST-III, 12 CST-IV participants). As a result, we have relatively reduced power in some of these statistical tests in stratified analyses. Some of the assumptions of traditional parametric statistical tests are sensitive to small sample sizes, and the use of non-parametric statistical tests, as was employed here, can overcome these assumptions with increased robustness to skewness and outliers. The use of a false discovery rate provided a further method for conservative interpretation of these results. We combined L. crispatus-dominated CST-I and L. iners-dominated CST-III because in this study, succinate was the only metabolite with abundance significantly different between samples belonging to CST-I compared to CST-III. Combining the two CSTs allowed us to increase our statistical power by comparing CST-I/III to CST-IV, however combining the L. crispatus and L.iners-dominated communities may not be functionally optimal. There is a growing body of research focused on L. iners32,100–103 that aims to evaluate its protective value as part of the vaginal microbiota. L. iners is commonly detected in healthy women, and interestingly in women with BV, as well as being among the first Lactobacillus spp. to recover after antibiotic treatment for BV104. Further, it is often considered to be a tipping point for some women at risk for BV104. Despite the small sample size, this study is unique in its use of metabolomics and microbial abundance data in combination with extensive participant behavioral data and its rigorous evaluation of smoking status by using quantification of carbon monoxide exhaled and cotinine in saliva. The depth of the analyses performed in this study, and the results obtained, may inform where to focus resources in a larger confirmatory study.

Conclusions

It is well-documented that a vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus spp. is associated with reduced risk for urogenital infections, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and urinary tract (UTIs) infections105. In this study, we determined that overall smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CST, but several key metabolites were elevated in smokers. Among women who were smokers and depauperate for Lactobacillus spp. (classified as CST-IV), we observed that they had significantly more perturbed metabolic profile than other CSTs when compared to their non-smoking counterparts. Biogenic amines were elevated in smokers and these metabolites have known roles in anaerobic bacterial proliferation, immune- and stress-resistance with a significant link to the development of BV, and possibly other reproductive tract infections. Women who smoke may have increased susceptibility to reproductive tract infections due to the observed increase in concentrations of BAs and the finding was even more pronounced among women who had low levels of Lactobacillus spp.

The metabolite profile of the vagina was strongly influenced by the resident microbiota as well as cigarette smoking in epidemiologic analyses that controlled for possible confounders. Detection of nicotine and its breakdown products in the vagina may serve as molecular biomarkers of smoking. Our results suggest that smoking is associated with several important metabolites present in the vagina that may have implications for women’s health. This study serves as a pilot for the development of future studies of the mechanisms linking smoking to poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

Methods

Sample Collection

Forty women self-collected mid-vaginal swabs during a single visit at the Center for Health Behavior Research at the University of Maryland School of Public Health (UMSPH). The study has previously been described30. In brief, smoking burden was determined by saliva cotinine testing, carbon monoxide exhalation levels and self-report of smoking habits on a set of comprehensive behavioral surveys. Participants were excluded if they had used an antibiotic or antimycotic in the 30 days prior. Four women were excluded from this analysis due to poor DNA quality affecting the normalization of the vaginal metabolome dataset (final sample size for analysis was 36 (17 smokers and 19 non-smokers) (Table 2). All participants provided written informed consent, and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland Baltimore (UMB), Montana State University and the UMSPH. All samples were collected and analysed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Table 2.

Factors associated with smoking status, Baltimore, MD (n=36)

| Non-smoker | Smoker | p-value1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Participant details | |||||

| Age | 0.011 | ||||

| 19–28 | 16 | 44 | 4 | 11 | |

| 29–38 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 17 | |

| 39–48 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 19 | |

| Marital status | 0.066 | ||||

| Single, never married | 17 | 47 | 8 | 22 | |

| Separated, divorce, widowed | 1 | 3 | 5 | 14 | |

| Married | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| Race | 0.170 | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 | 8 | 1 | 3 | |

| White | 8 | 22 | 4 | 11 | |

| African American/black | 4 | 11 | 10 | 28 | |

| Hispanic | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multi-racial | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Education level | 1.000 | ||||

| High School, up to 12 years | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| College and graduate, > 12 years | 19 | 53 | 16 | 44 | |

| Clinical | |||||

| CST | 0.011 | ||||

| I, L. crispatus-dominated | 13 | 36 | 4 | 11 | |

| III, L. iners-dominated | 4 | 11 | 3 | 8 | |

| IV, Low-Lactobacillus spp. | 2 | 6 | 10 | 28 | |

| Nugent’s Gram stain score | 0.000 | ||||

| 0–3 | 17 | 47 | 8 | 22 | |

| 4–6 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | |

| 7–9 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 19 | |

| Vaginal pH | 0.004 | ||||

| <=4.0 | 10 | 28 | 4 | 11 | |

| 4.1–5.5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | |

| 4.6–5.0 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 6 | |

| >=5.1 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 28 | |

| Self-reported symptoms | |||||

| Vaginal odor | 0.969 | ||||

| No | 15 | 42 | 16 | 44 | |

| Yes | 4 | 11 | 1 | 3 | |

| Vaginal irritation, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vaginal itching, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vaginal burning, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pain urinating, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vaginal discharge, 24 hours prior | 0.847 | ||||

| No | 14 | 39 | 14 | 39 | |

| Yes | 5 | 14 | 3 | 8 | |

| Hygiene | |||||

| Vaginal douche, 2 months prior | 0.108 | ||||

| No | 18 | 50 | 9 | 25 | |

| Yes | 1 | 3 | 7 | 19 | |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Menstruating currently | 0.075 | ||||

| No | 9 | 25 | 9 | 25 | |

| Yes | 10 | 28 | 8 | 22 | |

| Tampon or pad, 24 hours prior | 0.456 | ||||

| No pad, no tampon | 10 | 28 | 10 | 28 | |

| Pad only | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| Tampon only | 4 | 11 | 2 | 6 | |

| Tampon and pad | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| Not recorded | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| Sexual behaviors | |||||

| Lifetime number of sexual partners | 0.25 | ||||

| 0–6 | 13 | 36 | 3 | 8 | |

| 7+ | 6 | 17 | 12 | 33 | |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | |

| Number of sex partners, 2 months prior | 0.000 | ||||

| 0 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 6 | |

| 1 | 12 | 33 | 14 | 39 | |

| 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 3 | |

| Vaginal intercourse with a condom, 24 hours prior | 0.673 | ||||

| No vaginal intercourse | 14 | 39 | 9 | 25 | |

| Vaginal intercourse no condom | 3 | 8 | 6 | 17 | |

| Vaginal intercourse with condom | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | |

| Anal intercourse, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sex toy use, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lubricant use, 24 hours prior | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 | 53 | 17 | 47 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Partner type | 0.000 | ||||

| Regular | 10 | 28 | 12 | 33 | |

| Occasional | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| New | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not recorded | 6 | 17 | 5 | 14 | |

| Receptive oral sex, 24 hours prior | 0.543 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| No | 17 | 47 | 16 | 44 | |

| Digital penetration, 24 hours prior | 0.555 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 8 | 2 | 6 | |

| No | 16 | 44 | 15 | 42 | |

| Thong use, 24 hours prior | 0.000 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 17 | 3 | 8 | |

| No | 13 | 36 | 13 | 36 | |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

1p-value determined using Fisher’s exact test.

Sample Preparation for Metabolomics

Vaginal samples were eluted from swabs (Starplex rayon swab) in 200 µl phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to both gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with Orbitrap Elite accurate mass platforms (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sample processing and analysis was performed by Metabolon (Durham, NC, USA) using an automated MicroLab STAR® system (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). Recovery standards were added prior to the first step in the extraction process for quality control purposes. Sample preparation was conducted using a proprietary series of organic and aqueous extractions to remove the protein fraction while allowing maximum recovery of small molecules. The resulting extract was divided into two fractions: one for analysis by LC and one for analysis by GC. Samples were placed briefly on a TurboVap® (Zymark, Hopkinton, MA, USA) to remove the organic solvent. Each sample was then frozen and dried under vacuum. Samples were then prepared for the appropriate instrument, either LC-MS or GC-MS.

Liquid Chromatography and Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

LC-MS measurements were conducted on a Waters ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatograph (UPLC) and a ThermoFisher Scientific Orbitrap Elite high resolution/accurate mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which consisted of a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) source and orbitrap mass analyzer operated at a resolution 30,000 mass. The sample extract was dried then reconstituted in LC-compatible solvents, each of which contained eight or more injection standards at fixed concentrations to ensure injection and chromatographic consistency. One aliquot was analyzed using acidic positive ion optimized conditions and the other using basic negative ion optimized conditions in two independent injections using separate dedicated columns. Extracts reconstituted in acidic conditions were gradient eluted using water and methanol containing 0.1% formic acid, while the basic extracts, which also used water/methanol, contained 6.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The MS analysis alternated between MS and data-dependent MS2 scans using dynamic exclusion.

Samples for GC-MS analysis were re-dried under vacuum desiccation for a minimum of 24 hours prior to being derivatized under dried nitrogen using bistrimethyl-silyl-triflouroacetamide (BSTFA). The GC column was 5% phenyl and the temperature ramp is from 40° to 300 °C in a 16 min period. Samples were analyzed on a Thermo-Finnigan Trace DSQ fast-scanning single-quadrupole mass spectrometer using electron impact ionization. The instrument was tuned and calibrated for mass resolution and mass accuracy prior to use. Peaks in the GC-MS and LC-MS data were identified using Metabolon’s proprietary peak integration software to resolve sample metabolite peaks over noise. Complete details of methods describing metabolomic profiling are described in Lawton et al. (2008)106.

Compound Identification and Preparation

Spectra corresponding to each metabolite were identified by comparison to library entries of purified metabolite standards and their distinction from more than 1,000 other commercially available purified standard compounds. The combination of chromatographic properties and mass spectra gave an indication of a match to the specific biogenic amine compound or an isobaric entity. Results were manually curated to ensure that data were accurate and to remove any system artifacts, miss assignments, and background noise.

Taxonomic Assignment and Community State Type Profiling

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons from the vaginal tract of study participants were conducted in a prior study30. Briefly, the V1-V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was PCR amplified using the primers 27F-YM + 3107 and 534R57 and pyrosequenced using a Roche 454 FLX instrument. Species level assignments of Lactobacillus were performed using higher order Markov Chain models using the software speciateIT (speciateIT.sourceforge.net)33. For each sample, community state types (CSTs) were assigned to individual samples based on diversity and relative abundances of different phylotypes as defined in the work of Gajer and Brotman et al.108. The vaginal microbiota samples were categorized into CST-I (L. crispatus-dominated), CST-III (L. iners-dominated) and CST-IV (low-Lactobacillus/high strict and facultative anaerobes) (Table 2) Two other well-documented CSTs, CST-II (L. gasseri-dominated) and CST-V (L. jensenii-dominated) were not identified in this limited sample and are less commonly found even in larger surveys of women33.

Data Analyses

The metabolomic dataset was normalized to DNA concentration and missing values were imputed with the minimum detected value for that compound which essentially assigns values based on the sensitivity limit109. Data were then centered and scaled and the median was set equal to 1 prior to log transformation. Samples were visualized using a principal components analysis (PCA) (Figure S1). We performed quantile regression to estimate the median metabolite concentration differences 1) between smokers and non-smokers, 2) between CSTs and, 3) also with adjustment for confounding factors. P-values were obtained using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To correct for multiple tests, false discovery rate (FDR) and q-values were calculated for each compound where p = <0.05. Where a p-value estimates the proportion of all tests which will result in false positives (i.e. 5% where p-value = 0.05), a q-value estimates the proportion of significant tests that will result in false positives110. Initial investigations between Lactobacillus-dominated CST-I and CST-III yielded only one significant difference in the metabolite succinate (q-value = 0.009) with adjustment for smoking status. This metabolite was not identified as differing significantly (q-value = 0.05) in all further analyses, and therefore we grouped CST-I and CST-III for further binary analyses to increase power in comparisons to CST-IV. Fold change (FC) was calculated based on Guo et al.111 where FCi = xi - yi where i is metabolite of interest for the mean value of the control (x) and treatment (y).

We performed distance based linear modeling (DISTLM) by partitioning the distances of compounds using distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA)112, a form of multivariate multiple regression that can be performed directly on a distance or dissimilarity matrix. As the number of participants limits the number of variables that can be included in the model, we planned to include just two variables, in addition to our main factors of CST and smoking status. Initially we ran individual variables against the metabolite data and selected only those variables that were significant (p < = 0.05). These were age, race, marital status, education level, thong undergarment in the prior 24 hours, and vaginal douching in the two months prior. The dissimilarity matrix of vaginal metabolites was fitted with four of the variables listed in Table 2 and the final model was selected with the greatest adjusted R2 value.

Boxplots and heatmaps were constructed using the ggplot2113 and RColorBrewer (colorbrewer2.org) packages conducted in R version 3.1.2114. PCA, correlation coefficients, DISTLM and dbRDA plots were produced in Primer version 6115.

Data availability

The questionnaire and metabolome data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) under Accession number phs001386.v1.p1. Metagenomic sequence data were submitted to the public NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA391039.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grants K01-AI080974 (Brotman), R21-AI111145 (Yeoman), NR015495 (Ravel) the University of Maryland Cancer Epidemiology Alliance Joint Research Pilot Grant sponsored by the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center (Brotman), and the University of Maryland College Park / University of Maryland Baltimore Seed Grant (Brotman and Glover).

Author Contributions

R.M.B., J.R., J.M.R. and E.G. designed and implemented the study. T.N., J.B., M.S., R.M.B., C.Y., R.M. and D.R. performed analyses of samples and/or data. T.N., R.M.B. and C.Y. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14943-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

C. J. Yeoman, Email: carl.yeoman@montana.edu

R. M. Brotman, Email: rbrotman@som.umaryland.edu

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data from the National Health Interview Survey, 2016 (2017).

- 2.Fact sheet: Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. JAMA 309 (2013).

- 3.Eschenbach DA. Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis (Nonspecific Vaginitis): Role of the Laborator. 1984;6:134–138. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tripathi R, Dimri S, Bhalla P, Ramji S. Bacterial vaginosis and pregnancy outcome. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2003;83:193–195. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Oostrum N, De Sutter P, Meys J, Verstraelen H. Risks associated with bacterial vaginosis in infertility patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction. 2013;28:1809–1815. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldkamp ML, et al. Case-control study of self reported genitourinary infections and risk of gastroschisis: findings from the national birth defects prevention study, 1997-2003. Bmj. 2008;336:1420–1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39567.509074.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagaitkar J, Demuth DR, Scott DA. Tobacco use increases susceptibility to bacterial infection. 2008;4:12–10. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson PG, Platz-Christensen JJ, Sundström E. Is bacterial vaginosis a sexually transmitted disease? International journal of STD & AIDS. 1991;2:362–364. doi: 10.1177/095646249100200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellberg D, Nilsson S, Mårdh PA. Bacterial vaginosis and smoking. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2000;11:603–606. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay PE, et al. A longitudinal study of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1995;3:320. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson DB, et al. Vaginal symptoms and bacterial vaginosis (BV): how useful is self-report? Development of a screening tool for predicting BV status. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007;135:1369–1375. doi: 10.1017/S095026880700787X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller GC, McDermott R, McCulloch B, Fairley CK, Muller R. Predictors of the prevalence of bacterial STI among young disadvantaged Indigenous people in north Queensland, Australia. Sexually transmitted infections. 2003;79:332–335. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherpes TL, Hillier SL, Meyn LA, Busch JL, Krohn MA. A delicate balance: risk factors for acquisition of bacterial vaginosis include sexual activity, absence of hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli, black race, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:78–83. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318156a5d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swartzendruber A, Sales JM, Brown JL, DiClemente RJ, Rose ES. Correlates of Incident Trichomonas vaginalis Infections Among African American Female Adolescents. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41:240–245. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Risk factors for infection with herpes simplex virus type 2: Role of smoking, douching, uncircumcised males, and vaginal flora. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:405–410. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wangnapi RA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis infection in pregnant women in Papua New Guinea. Sexually transmitted infections. 2015;91:194−+. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcone, V. et al. Epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis endocervical infection in a previously unscreened population in Rome, Italy, 2000 to 2009. 17, 16–23 (2012). [PubMed]

- 18.Miller CS, White DK. Human papillomavirus expression in oral mucosa, premalignant conditions, and squamous cell carcinoma: A retrospective review of the literature. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 1996;82:57–68. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillison, M. L. et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. 100, 407–420 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Castellsagué, X. & Muñoz, N. Chapter 3: Cofactors in human papillomavirus carcinogenesis–role of parity, oral contraceptives, and tobacco smoking. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monographs 20–28 (2003). [PubMed]

- 21.Garrett LR, Perez-Reyes N, Smith PP, McDougall JK. Interaction of HPV-18 and nitrosomethylurea in the induction of squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:329–332. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nischan, P., Ebeling, K. & Schindler, C. Smoking and Invasive Cervical-Cancer Risk - Results From a Case-Control Study. 128, 74–77 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Khan AM, Freeman-Wang T, Pisal N, Singer A. Smoking and multicentric vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:123–125. doi: 10.1080/01443610802668938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2010;34:J258–J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simons AM, Phillips DH, Coleman DV. Damage to DNA in Cervical Epithelium Related to Smoking. Tobacco. 1994;49:186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bornstein, J., Rahat, M. A. & Abramovici, H. Etiology of Cervical Cancer: Current Concepts. 50, 146 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.McCann, M. F. et al. Nicotine and cotinine in the cervical mucus of smokers, passive smokers, and nonsmokers. 1, 125–129 (1992). [PubMed]

- 28.Winkelstein, W. Smoking and Cervical-Cancer - Current Status - a Review. 131, 945–957 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Biedermann, L. et al. Smoking cessation induces profound changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans. 8, e59260 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Brotman RM, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and the vaginal microbiota: a pilot study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014;14:471. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. Vaginal pH and Microbicidal Lactic Acid When Lactobacilli Dominate the Microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:ARTN e80074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macklaim JM, Gloor GB, Anukam KC, Cribby S, Reid G. At the crossroads of vaginal health and disease, the genome sequence of Lactobacillus iners AB-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4688–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000086107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravel J, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta SD, et al. The Vaginal Microbiota over an 8- to 10-Year Period in a Cohort of HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert, A. Y. K. et al. A Study of the Vaginal Microbiome in Healthy Canadian Women Utilizing cpn 60-Based Molecular Profiling Reveals Distinct Gardnerella Subgroup Community State Types. 10, e0135620 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Srinivasan, S. et al. More Than Meets the Eye: Associations of Vaginal Bacteria with Gram Stain Morphotypes Using Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis. 8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Lurie JG, Hillier SL. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319–325. doi: 10.1086/375819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin HL, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1863–1868. doi: 10.1086/315127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brotman RM, et al. Bacterial Vaginosis Assessed by Gram Stain and Diminished Colonization Resistance to Incident Gonococcal, Chlamydial, and Trichomonal Genital Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202:1907–1915. doi: 10.1086/657320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King CC, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the natural history of human papillomavirus. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;2011:319460–8. doi: 10.1155/2011/319460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallo MF, et al. Bacterial Vaginosis, Gonorrhea, and Chlamydial Infection Among Women Attending a Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic: A Longitudinal Analysis of Possible Causal Links. Annals of epidemiology. 2012;22:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balkus JE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV-1-negative women. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41:123–128. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghartey, J. P. et al. Lactobacillus crispatus Dominant Vaginal Microbiome Is Associated with Inhibitory Activity of Female Genital Tract Secretions against Escherichia coli. 9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Klupczynska A, Derezinski P, Kokot ZJ. Metabolomics in Medical Sciences - Trends, Challenges and Perspectives. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 2015;72:629–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeoman, C. J. et al. A multi-omic systems-based approach reveals metabolic markers of bacterial vaginosis and insight into the disease. 8, e56111 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Srinivasan S, et al. Bacterial communities in women with bacterial vaginosis: high resolution phylogenetic analyses reveal relationships of microbiota to clinical criteria. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMillan A, et al. A multi-platform metabolomics approach identifies highly specific biomarkers of bacterial diversity in the vagina of pregnant and non-pregnant women. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:14174. doi: 10.1038/srep14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitali, B. et al. Vaginal microbiome and metabolome highlight specific signatures of bacterial vaginosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol 1–10 10.1007/s10096-015-2490-y (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Aroutcheva AA, Simoes JA, Faro S. Antimicrobial protein produced by vaginal Lactobacillus acidophilus that inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;9:33–39. doi: 10.1155/S1064744901000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turovskiy Y, et al. Susceptibility of Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms to natural antimicrobials subtilosin, epsilon-poly-L-lysine, and lauramide arginine ethyl ester. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;2012:284762. doi: 10.1155/2012/284762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braga PC, Dal Sasso M, Culici M, Spallino A. Inhibitory activity of thymol on native and mature Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms: in vitro study. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2010;60:675–681. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanjee, U. & Houry, W. A. Mechanisms of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. 67, 65–81 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Nasrallah, G. K. et al. Legionella pneumophila requires polyamines for optimal intracellular growth. 193, 4346–4360 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Jelsbak L, Thomsen LE, Wallrodt I, Jensen PR, Olsen JE. Polyamines are required for virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goytia M, Shafer WM. Polyamines can increase resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to mediators of the innate human host defense. Infection and immunity. 2010;78:3187–3195. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01301-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson, T. M. et al. Vaginal biogenic amines: biomarkers of bacterial vaginosis or precursors to vaginal dysbiosis? 6, 253 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Ravel J, et al. Daily temporal dynamics of vaginal microbiota before, during and after episodes of bacterial vaginosis. Microbiome. 2013;1:1. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hukkanen J, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57:79–115. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baheiraei A, Banihosseini SZ, Heshmat R, Mota A, Mohsenifar A. Association of self-reported passive smoking in pregnant women with cotinine level of maternal urine and umbilical cord blood at delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dempsey D, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Accelerated metabolism of nicotine and cotinine in pregnant smokers. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2002;301:594–598. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:188–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poppe WA, Peeters R, Daenens P, Ide PS, Vanassche FA. Tobacco Smoking and the Uterine Cervix - Cotinine in. Blood, Urine and Cervical Fluid. 1995;39:110–114. doi: 10.1159/000292390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schiffman MH, et al. Biochemical epidemiology of cervical neoplasia: measuring cigarette smoke constituents in the cervix. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3886–3888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mietz, J. L. & Karmas, E. Polyamine and histamine content of rockfish, salmon, lobster, and shrimp as an indicator of decomposition. Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (USA) (1978).

- 65.Hussain A, et al. High-affinity olfactory receptor for the death-associated odor cadaverine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:19579–19584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318596110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen KC, et al. Amine content of vaginal fluid from untreated and treated patients with nonspecific vaginitis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1979;63:828–835. doi: 10.1172/JCI109382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sobel JD, et al. Diagnosing vaginal infections through measurement of biogenic amines by ion mobility spectrometry. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012;163:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benowitz NL. Clinical Pharmacology of Nicotine: Implications for Understanding, Preventing, and Treating Tobacco. Addiction. 2008;83:531–541. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strom AR, et al. Trimethylamine oxide: a terminal electron acceptor in anaerobic respiration of bacteria. Journal of general microbiology. 1979;112:315–320. doi: 10.1099/00221287-112-2-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koumans EH, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2007;34:864–869. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074e565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li P, Beck WD, Callahan PM, Terry AVJ, Bartlett MG. Quantitation of cotinine and its metabolites in rat plasma and brain tissue by hydrophilic interaction chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HILIC-MS/MS) Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2012;907:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brunnemann KD, Kagan MR, Cox JE, Hoffmann D. Chemical Studies on Tobacco-Smoke.87. Determination of Benzene, Toluene and 1,3-Butadiene in Cigarette-Smoke by Gc-Msd. Exp Pathol. 1989;37:108–113. doi: 10.1016/S0232-1513(89)80026-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piot, P., Van Dyck, E., Totten, P. A. & Holmes, K. K. Identification of Gardnerella (Haemophilus) vaginalis. 15, 19–24 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Aroutcheva, A. A., Simoes, J. A., Behbakht, K. & Faro, S. Gardnerella vaginalis isolated from patients with bacterial vaginosis and from patients with healthy vaginal ecosystems. 33, 1022–1027 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Spiegel, C. A. et al. Gardnerella-Vaginalis and Anaerobic-Bacteria in the Etiology of Bacterial (Nonspecific) Vaginosis. 41–46 (1983). [PubMed]

- 77.Swidsinski A, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:97 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leitich H, et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: A meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:139–147. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Delbridge LM, O’Riordan MX. Innate recognition of intracellular bacteria. Current opinion in immunology. 2007;19:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strom K, Sjogren J, Broberg A, Schnurer J. Lactobacillus plantarum MiLAB 393 Produces the Antifungal Cyclic Dipeptides Cyclo(L-Phe-L-Pro) and Cyclo(L-Phe-trans-4-OH-L-Pro) and 3-Phenyllactic Acid. 2002;68:4322–4327. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4322-4327.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piuri M, Sanchez-Rivas C, Ruzal SM. Adaptation to high salt in Lactobacillus: role of peptides and proteolytic enzymes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;95:372–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Magnusson J, Ström K, Roos S, Sjögren J, Schnürer J. Broad and complex antifungal activity among environmental isolates of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;219:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)01207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Houston DR, et al. Structure-based exploration of cyclic dipeptide chitinase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5713–5720. doi: 10.1021/jm049940a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang EJ, Chang HC. Purification of a new antifungal compound produced by Lactobacillus plantarum AF1 isolated from kimchi. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;139:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sinha S, Srivastava R, De Clercq E, Singh RK. Synthesis and Antiviral Properties of Arabino and Ribonucleosides of 1,3‐Dideazaadenine, 4‐Nitro‐1, 3‐dideazaadenine and Diketopiperazine. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2004;23:1815–1824. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200040614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kwon, O. S., Park, S. H., Yun, B. S., Pyun, Y. R. & Kim, C. J. Cyclo(Dehydroala-L-Leu), an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor from Penicillium sp F70614. 53, 954–958 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Olmsted SS, Meyn LA, Rohan LC, Hillier SL. Glycosidase and proteinase activity of anaerobic gram-negative bacteria isolated from women with bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:257–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wiggins R, Hicks SJ, Soothill PW, Millar MR, Corfield AP. Mucinases and sialidases: their role in the pathogenesis of sexually transmitted infections in the female genital tract. Sexually transmitted infections. 2001;77:402–408. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.6.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Briselden AM, Moncla BJ, Stevens CE, Hillier SL. Sialidases (neuraminidases) in bacterial vaginosis and bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:663–666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.663-666.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McGregor JA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with prematurity and vaginal fluid mucinase and sialidase: Results of a controlled trial of topical clindamycin cream. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1048–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(94)70098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Straus DC, Mattingly SJ, Milligan TW, Doran TI, Nealon TJ. Protease production by clinical isolates of type III group B streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980;12:421–423. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.421-423.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Volpe GE, et al. Associations of cocaine use and HIV infection with the intestinal microbiota, microbial translocation, and inflammation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:347–357. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khan MR, et al. Non-injection and injection drug use and STI/HIV risk in the United States: the degree to which sexual risk behaviors versus sex with an STI-infected partner account for infection transmission among drug users. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1185–1194. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cavazos-Rehg PA, et al. Risky sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases: a comparison study of cocaine-dependent individuals in treatment versus a community-matched sample. Aids Patient Care St. 2009;23:727–734. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uguz F, et al. Antidepressants and menstruation disorders in women: a cross-sectional study in three centers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Urban, R. J. & Veldhuis, J. D. A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine hydrochloride, modulates the pulsatile release of prolactin in postmenopausal women. 164, 147–152 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Srinivasan, S. et al. Metabolic signatures of bacterial vaginosis. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Gika HG, Theodoridis GA, Plumb RS, Wilson ID. Current practice of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in metabolomics and metabonomics. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2014;87:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Courant, F., Antignac, J.-P., Dervilly-Pinel, G. & Le Bizec, B. Basics of mass spectrometry based metabolomics. 14, 2369–2388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Fredricks DN. Molecular methods to describe the spectrum and dynamics of the vaginal microbiota. Anaerobe. 2011;17:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Verstraelen H, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the vaginal microflora in pregnancy suggests that L. crispatus promotes the stability of the normal vaginal microflora and that L. gasseri and/or L. iners are more conducive to the occurrence of abnormal vaginal microflora. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Witkin, S. S. et al. Influence of vaginal bacteria and D- and L-lactic acid isomers on vaginal extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer: implications for protection against upper genital tract infections. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.McMillan A, Macklaim JM, Burton JP, Reid G. Adhesion of Lactobacillus iners AB-1 to human fibronectin: a key mediator for persistence in the vagina? Reprod Sci. 2013;20:791–796. doi: 10.1177/1933719112466306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mayer BT, et al. Rapid and profound shifts in the vaginal microbiota following antibiotic treatment for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:793–802. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Martin, D. H. The microbiota of the vagina and its influence on women’s health and disease. 343, 2–9 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Lawton, K. A. et al. Analysis of the adult human plasma metabolome. 10.2217/14622416.9.4.3839, 383–397 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Frank JA, et al. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74:2461–2470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gajer P, et al. Temporal Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiota. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:132ra52–132ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nature protocols. 2011;6:743–760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vinaixa M, et al. A Guideline to Univariate Statistical Analysis for LC/MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics-Derived Data. Metabolites. 2012;2:775–795. doi: 10.3390/metabo2040775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Guo L, et al. Rat toxicogenomic study reveals analytical consistency across microarray platforms. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24:1162–1169. doi: 10.1038/nbt1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Legendre, P. & Anderson, M. J. Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis: Testing Multispecies Responses in Multifactorial Ecological Experiments. 69, 1 (1999).

- 113.Warnes, G. R. et al. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. R package version2 (2009).

- 114.Ihaka, R. & Gentleman, R. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. 5, 299–314 (1996).

- 115.Clarke, K. & Gorley, R. PRIMER v6: User manual/tutorial: PRIMER E. (Plymouth) 2006.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire and metabolome data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) under Accession number phs001386.v1.p1. Metagenomic sequence data were submitted to the public NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA391039.