Abstract

The Tat machinery catalyzes the transport of folded proteins across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and the thylakoid membrane in plants. Using fluorescence quenching and cross-linking approaches, we demonstrate that the Escherichia coli TatBC complex catalyzes insertion of a pre-SufI signal peptide hairpin that penetrates about halfway across the membrane bilayer. Analysis of 512 bacterial Tat signal peptides using secondary structure prediction and docking algorithms suggest that this hairpin interaction mode is generally conserved. An internal cross-link in the signal peptide that blocks transport but does not affect binding indicates that a signal peptide conformational change is required during translocation. These results suggest, to our knowledge, a novel hairpin-hinge model in which the signal peptide hairpin unhinges during movement of the mature domain across the membrane. Thus, in addition to enabling the necessary recognition, the interaction of Tat signal peptides with the receptor complex plays a critical role in the transport process itself.

Introduction

Bacteria and archaea utilize two general export systems to translocate proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane to the periplasm. The Sec machinery threads unfolded polypeptides through a gated, permanent pore utilizing ATP and the proton-motive force (pmf). The Tat machinery transports folded proteins, requires at least one component of the pmf, and assembles upon demand (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). “Tat” (twin arginine translocation) signal peptides are characterized by a RRXFLK consensus motif, which includes the twin-arginine namesake (RR-motif) (7, 8). A structurally and functionally conserved Tat system is found in plant thylakoids (2, 9). Tat substrates perform key roles in many cellular processes, including respiration, photosynthetic energy metabolism, nitrogen fixation, cell division, cell motility, and virulence (10).

In Escherichia coli, Tat-dependent transport minimally requires TatA, TatB, and TatC (8). TatA and TatB both have an N-terminal membrane domain, followed by an amphipathic helix, and a highly charged, intrinsically disordered C-terminal tail (4). TatC, the largest and most conserved of the three Tat components, has six transmembrane helices spanning the inner membrane (11, 12). TatB and TatC form a receptor complex (13, 14, 15) in which TatC provides numerous critical interactions with Tat signal peptides (16, 17). TatB modulates the signal peptide’s interaction with TatC and is in close proximity to both the bound signal peptide and the mature domain (18, 19). X-ray structures of TatC from Aquifex aeolicus reveal a glovelike shape (11, 12). Although the signal peptide binding site and mode of interaction has not been definitively established, two glutamic acid residues on the TatC cytoplasmic face are essential for a high affinity signal peptide interaction (12) and likely interact with the RR-motif. A deep groove in the side of TatC (the “palm” of the “glove”) exposed to the bilayer interior seems ideally suited to accommodate the signal peptide in a membrane inserted configuration (11).

Signal peptide binding is clearly an important trigger for initiating the Tat transport process, and therefore, a significant effort has sought to establish the identity and nature of this interaction. Numerous studies have verified the stability and 1:1 stoichiometry of the TatBC heterodimer (20, 21, 22, 23). However, the oligomerization state of TatBC heterodimers remains controversial. Models have been proposed in which the substrate binds to a central cavity formed by a dimer, trimer, or a tetramer (24, 25, 26). Single particle electron microscopy suggests that the substrate interacts with the outside of a substantially larger TatBC complex (27), consistent with biochemical studies that support an octomeric TatBC complex (13, 14, 20, 28). Because the TatBC interaction with Tat signal peptides is pmf-independent and of relatively high affinity (KD ≈ 10–20 nM) (29), the properties of the receptor-substrate complex can be readily probed. Cross-linking studies have identified residues of TatB and TatC in proximity to signal peptides (16, 17, 18, 24, 30, 31). However, the structural features of the signal peptide binding site and the conformation of the bound signal peptide in regard to the membrane bilayer remains uncertain.

The Tat machinery performs the challenging task of transporting globular proteins of variable diameters (up to ∼6 nm) through a membrane bilayer without collapsing essential ion gradients (32, 33). The composition of the transient translocation pore has remained elusive. Electron microscopy revealed that homo-oligomers of TatA form ring-shaped structures with a pore size of 3–7 nm, consistent with the expected dimensions of a variable diameter Tat translocation channel (32). TatA molecules oligomerize in the presence of transport substrate and the pmf in ∼20–40 s (15, 29), suggesting that Tat translocation pores assemble de novo in response to the formation of cargo-receptor complexes. In some models, the translocation pore is not formed entirely from TatA, but also includes TatB and TatC (24, 25, 26).

Exactly when and how the signal peptide penetrates the membrane bilayer is a matter of considerable debate. Tat signal peptides bind to membranes devoid of Tat proteins (34, 35, 36, 37), suggesting that Tat precursors initially bind to the membrane lipids and then diffuse to the TatBC complex. Based on protease protection, it was concluded that membrane-bound signal peptides spontaneously insert into the membrane (38, 39, 40). In contrast, premature signal peptide cleavage in membranes with TatC alone suggested that TatC is a signal peptide insertase (18), thus arguing against spontaneous signal peptide insertion into the membrane bilayer. Most models postulate that the signal peptide binds to the interior of an oligomeric TatBC receptor complex (11, 16, 24, 25, 26, 41, 42).

The goal of the work reported here was to clarify how Tat signal peptides interact with the membrane lipids and with the TatBC complex. Specifically, we sought to determine the penetration depth of the signal peptide, its environment, and how these might influence subsequent steps of the transport process. Using nitroxide fluorescence quenching and cross-linking approaches, we establish that the TatBC complex inserts the pre-SufI signal peptide into the membrane in a hairpin configuration that extends about halfway across the bilayer. Cross-linking studies indicate that the C-terminal half of this hairpin contacts TatB. Docking simulations of Tat signal peptides with the TatC structure plus the TatB membrane domain support the hypothesis that the large groove on the side of TatC accommodates the signal peptide hairpin. These results, among others, motivated, to our knowledge, a novel hairpin-hinge model of Tat translocation, which is supported by signal peptide cross-linking experiments designed to test this model. This model elucidates how the precursor protein remains continuously bound to the TatBC complex while the mature domain migrates through the translocation pore.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids

E. coli strains MC4100(DE3) and MC4100ΔTatABCDE were described earlier (8, 43). Bacterial cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (44) at 37°C supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL). Plasmids encoding single cysteine mutants of pre-SufI were generated from pSufI-IAX by the QuikChange protocol (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA; see Table S1 for forward and reverse primers). pSufI-IAX encodes pre-SufI with mutations C17I and C295A and a stop codon after the C-terminal 6×His-tag (36). Plasmids pTatBC, pTatAC, and pTatC, which encode the indicated Tat proteins under arabinose control, were generated by deleting TatA, TatB, and TatAB sequences from pTatABC (43), respectively. All mutants were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA).

Immunoblotting

SufI was detected by immunoblotting using rabbit polyclonal anti-SufI antibodies (43) or mouse anti-6×His antibodies (No. MA1-21315; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), both at 1:10,000 dilution. TatA, TatB, and TatC were detected using anti-TatA, anti-TatB, and anti-TatC antibodies (18, 43) (1:5000 dilutions). All blots were probed in 1× PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) with 3% nonfat dry milk, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.5% Tween-20. Polyclonal goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) and polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (Cat. No. R-21455; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used as secondary antibodies (both at 1:10,000), and bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (45). Band intensities were quantified with a phosphorimager (model FX; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Isolation of inverted membrane vesicles

Inverted membrane vesicles (IMVs) were isolated from E. coli strains MC4100(DE3) and MC4100ΔTatABCDE with or without overproduced Tat proteins (induced with 0.7% arabinose), as described (29). The translucent brown band on the 0.5 M sucrose cushion contained the inner membrane fraction. Total protein was quantified as the absorbance at 280 nm in 2% SDS. Typical IMV stock solutions had an A280 ≈ 45–55.

Protein expression, purification, and dye labeling

Pre-SufI cysteine mutants were overproduced in BL21(DE3) (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). All proteins were purified under native conditions by Ni-NTA chromatography. Luria-Bertani cultures (500 mL) were incubated at 37°C until the A600 reached 0.5–0.6. The pH of the culture was raised with 25 mL of 100 mM Tris, 25 mM CAPS, pH 9.0 and induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 2.0 h. Cultures were chilled in an ice-bath and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were rapidly resuspended on ice in 40 mL lysis buffer (0.1% CelLytic B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 100 mM Tris, 25 mM CAPS, pH 9.0) containing 0.5 M urea, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.2% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (10 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; from 0.2 M stock solution in isopropanol), 100 μg/mL trypsin inhibitor, 20 μg/mL leupeptin, and 100 μg/mL pepstatin). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the cleared supernatant was stirred with 2 mL Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) that had been preequilibrated with lysis buffer for 10 min on ice (36). The protein-saturated resin was transferred to a 10 × 1 cm column, and washed as described earlier (5). The 6×His-tagged protein was eluted with 250 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 50% glycerol, and pH 8.0. Pre-SufI concentrations were determined by SDS-PAGE using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Spot intensities after Coomassie Blue staining were quantified with a model FX phosphorimager. Purified pre-SufI proteins were reduced with 1 mM tris[2-carboxyethylphosphine] hydrochloride (TCEP) for 10 min and labeled with a 10-fold molar excess of BODIPY-FL maleimide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. Reactions were quenched with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), and excess dye was removed using a Zeba Spin Desalting Column, 7K MWCO (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of BODIPY-FL in solutions was determined from their absorbance (ε504 = 90,000 M−1 cm−1). Typical dye-to-protein concentration ratios after labeling suggested that 80–90% of the cysteines were successfully tagged.

Membrane binding

Membrane binding reactions (35 μL) were performed in Binding Buffer (BB; 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 200 mM sucrose, 1.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (40,000 average molecular weight), 25 mM MOPS, 25 mM MES, pH 8.0) as described (36). In short, pre-SufI (90 nM) was incubated with IMVs (A280 = 2) at 37°C for 10 min in protein LoBind microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 16,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C to sediment the IMVs. The pellets were washed with BB (200 μL) and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The reisolated precursor-bound IMVs were suspended in BB for further experiments.

Transport reactions

In vitro Tat transport assays (35 μL) were performed in Translocation Buffer (5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 200 mM sucrose, 57 μg/mL bovine serum albumin, 25 mM MOPS, and 25 mM MES, pH 8.0) (5). Solutions of IMVs (A280 = 5) and pre-SufI (90 nM) were prewarmed at 37°C for 5 min before the addition of NADH (4 mM). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then quenched in an ice bath for 2 min. The samples were digested with proteinase K (0.73 mg/mL) for 40 min at room temperature. Digestions were quenched with PMSF (68 mM), diluted twofold with 2× Gel Buffer (4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue, 0.4% β-ME, 10 M urea, 200 mM Tris, pH 6.8), and incubated in a boiling water bath for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged briefly at 16,000 × g, and then were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE with known standards. Gels were electroblotted onto PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with anti-SufI antibodies.

Fluorescence quenching

All fluorescence measurements were made on an SLM 8100 spectrofluorometer (OLIS, Bogart, GA). For nitroxide quenching assays, samples of IMV-bound BODIPY-labeled precursor protein were resuspended in 0.8 mL BB, aliquoted into a 4 × 4 mm quartz microcell maintained at 37°C, and mixed with a 2 × 2 mm magnetic Teflon-coated stir bar. Fluorescence emission intensity was collected continuously using excitation and emission wavelengths of 495 and 510 nm, respectively, with a typical bandpass of 4 nm. The nitroxide quenchers, 3-Carboxy-PROXYL (3-CP) and 5-DOXYL and 16-DOXYL stearic acids (5-D and 16-D; Sigma-Aldrich), were solubilized in DMSO (3 M for 3-CP; 20 mM for 5-D and 16-D) and were used to probe the accessibility of the BODIPY probe. Averaged fluorescence readings were recorded at least 200 s after each addition of nitroxide quencher to allow the signal to stabilize. For the urea dependence of tryptophan fluorescence, purified pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) (10 nM) was suspended in 0.8 mL of BB and the fluorescence was measured continuously using excitation and emission wavelengths of 295 and 340 nm, respectively. Readings were recorded at least 300 s after each addition of 9 M urea in BB. For reduced pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C), the protein was pretreated with 1 mM TCEP.

Protease susceptibility

Pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) (0.2 mM) was preincubated with low (0.35 M) or high (2 M) urea concentrations in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.2 for 15 min, and then incubated with 10 μg/mL proteinase K (≥30 U/mg; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. Digestions were stopped by addition of 3 μL 0.2 M PMSF.

Photocross-linking

For UV photocross-linking reactions, single cysteine mutants of pre-SufI were labeled with 4-(N-maleimido)benzophenone (46) (Sigma-Aldrich) and repurified using the protocol used to attach the BODIPY dye. Benzophenone-modified pre-SufI was incubated with IMVs for 10 min at 37°C in LoBind tubes as described for the membrane binding assay. Cross-linking was initiated in a Stratalinker UV Crosslinker 1800 (Agilent Technologies) by 254 nm irradiation for 5 min in an ice-bath (open upright tubes within 1 inch of the UV bulbs). Irradiated samples were centrifuged at 16,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C to sediment precursor protein bound to IMVs. Reisolated IMVs were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. For transport assays following photocross-linking, the irradiated samples were incubated for 10 min in a 37°C water-bath before the addition of NADH (4 mM). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then quenched in an ice bath for 2 min. The samples were centrifuged at 16,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C and the pellets were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. To reduce TatC aggregation, samples that were probed for TatC cross-links were not boiled.

Mass spectrometry

Purified pre-SufI samples were digested with trypsin using the filter-aided sample preparation method (47) with slight modifications to detect the disulfide under nonreducing conditions. Samples (200 μL, ∼50 μg) were divided into two equal aliquots, which were then denatured by the addition of 250 μL 8 M urea, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5 with or without the disulfide-reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT; 100 mM) in a microfilter centrifuge tube with a 10-kDa cutoff-filter (Nanosep 10K; Pall, Port Washington, NY). Samples were washed three times with 500 μL NH4HCO3 buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0), and then digested with sequencing grade trypsin (1:50 enzyme/protein; reaction volume = 50 μL) for 16 h at 37°C. The digestion products were then filtered through a 10-kDa microfilter (described earlier) and air-dried with a stream of nitrogen gas. Samples were solubilized in 20 μL 0.1% formic acid (FA) and injected (3 μL) into the mass spectrometer.

Mass spectrometry (MS) experiments were performed at the University of Texas Medical Branch Mass Spectrometry Core Facility. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Nano LC-MS/MS) was performed on an Orbitrap Fusion system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) with collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron transfer dissociation capability, coupled with an UltiMate 3000 nano-LC and autosampler (Dionex). Samples were injected into a nano-trap (C18 PepMap 100, 100 μm (i.d.) × 1 cm (length)) that was connected to a C18 reverse-phase home-packed column containing 5 μm SB-C18 beads (75 μm × 10 cm, ZORBAX; Agilent Technologies) using a flow rate of 400 nL/min. Solutions A (5% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA) and B (100% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA) were used to separate the polypeptide fragments as follows: 0–5 min, isocratic with 0% B; 5–45 min, linear gradient to 50% B; 45–52 min, linear gradient to 90% B; 52–60 min, linear gradient to 0% B. The eluent was sprayed through a charged emitter tip (PicoTip Emitter, 10 ± 1 μm; New Objective, Woburn, MA) into the mass spectrometer under the following conditions: +2.2 kV tip voltage, FTMS mode (Orbitrap; Dionex) for MS acquisition of precursor ions (resolution 120,000 full width half-maximum), and ITMS mode (linear ion trap) for subsequent MS/MS of the top 10 most abundant ions. CID was used to perform MS/MS.

The MS data were analyzed by searching for expected m/z values assuming +2, +3, and +4 ionizations states using the Xcalibur Qual Browser (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In silico fragmentation signatures of cross-linked peptides were calculated using the NIST Mass and Fragment Calculator Software (http://www.nist.gov/mml/bmd/bioanalytical/massfragcalc.cfm) and compared with observed fragmentation patterns. The disulfide percentage was estimated by comparing the total ion intensities for one of the cysteine containing peptides (residues 25–43) between the DTT treated and nontreated samples normalized to a closely eluting peptide, which was assumed to be invariant in the presence and absence of DTT.

Purification of pre-SufI with an internally cross-linked signal peptide

As mass spectrometry ion intensities indicated that the internally disulfide-linked form of as-isolated pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) was only ∼10–15% of the purified protein, the fraction of cross-linked protein was increased by incubating the sample with SulfoLink coupling resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which is activated with thiol-reactive iodoacetyl groups and thus binds the reduced form of the protein, and then recovering the unbound protein, most of which was cross-linked. The resin slurry (1 mL) was mixed with four resin-bed volumes of equilibration buffer (20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 50% glycerol, pH 8.0) and centrifuged (1,000 × g, 5 min). This equilibration/wash step was repeated five times. After the final wash, purified pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) (0.5 mL) was added to the resin. The mixture was shaken for 3 h at 4°C and centrifuged (1000 × g, 5 min). The supernatant contained ∼60% internally disulfide-linked pre-SufI(S12C/A25C), as estimated from MS ion intensities using a single cysteine mutant, pre-SufI(S12C), and DTT-reduced pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) as controls.

Signal peptide structural propensity and molecular docking

The secondary structure of E. coli Tat signal peptides was modeled using PEP-FOLD 1.5 (48). To probe the generality of the observed features (see Results), the probability of predicted secondary structures (helix, β, disordered) at different positions was determined using JPRED (49, 50, 51) for 512 bacterial Tat signal peptides (PROSITE: PS51318, http://prosite.expasy.org/doc/PS51318; 535 proteins manually curated to 512, includes both predicted and experimentally verified sequences). The secondary structures of five representative signal peptides were docked with the TatBC complex using ZDOCK (52). The TatBC complex was generated by docking residues L7-G21 of the TatB (PDB: 2MI2) membrane domain (53) onto the TatC structure (SWISS-MODEL: P69423). The sites of interaction between TatC (M205 and L206 of transmembrane domain 5 (TM5)) and TatB (L9, L10, and L11) were identified by cysteine-cysteine cross-linking results (12).

Fluorescence quenching

The Stern-Volmer equation describing the effects of both dynamic and static quenching is

| (1) |

where F0 is the initial fluorescence, F is the fluorescence measured in the presence of a quencher at concentration [Q], and KD and KS are the dynamic and static quenching constants, respectively (54). For all the mutant-quencher combinations in Fig. 2, a single quenching constant for each species present (lipid- and translocon-bound forms) was sufficient to fit the quenching data. Because static and dynamic quenching constants are indistinguishable in these types of quenching experiments and nitroxide quenching does not require contact with the fluorophore (55), we assumed that the quenching constants required to fit these data were the dynamic quenching constants. Consequently, the ΔTat data (Fig. 3, A–C) were fit to

| (2) |

For fluorescent pre-SufI bound to Tat++ IMVs, the lipid- and translocon-bound populations were expected to respond differently to the nitroxide quenchers. The total fluorescence in the absence of quencher is

| (3) |

where the subscripts L and T indicate the fluorescence arising from the precursor bound to the lipid and to the Tat translocon, respectively. In the presence of quencher,

| (4) |

and, using Eq. 2,

| (5) |

where it is assumed that the fluorescence emitted from the lipid- and translocon-bound precursor proteins was quenched according to the different dynamic quenching constants KD,L and KD,T, respectively. Dividing by F0 and taking the reciprocal yields the Stern-Volmer equation for a solution containing a fluorophore in two distinct environments:

| (6) |

where α = F0,T/F0 is the translocon-bound fraction.

Figure 2.

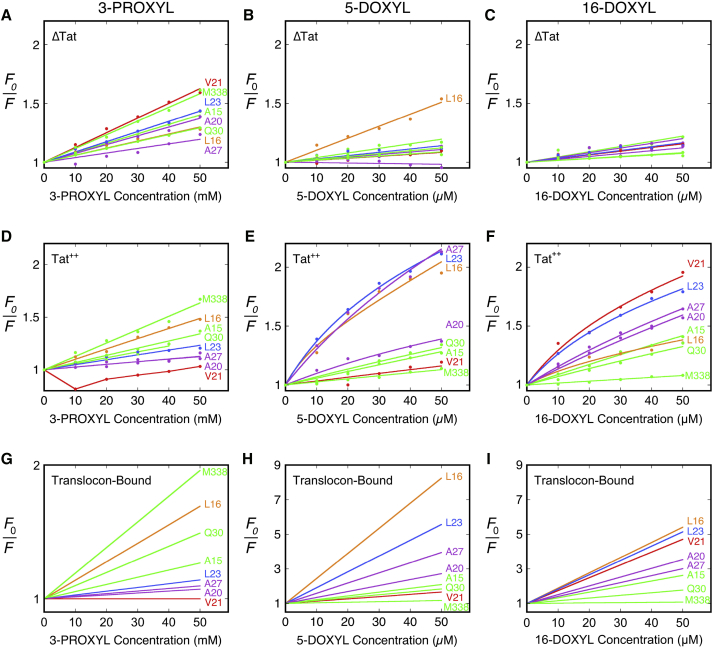

Stern-Volmer quenching of BODIPY-tagged pre-SufI single cysteine mutants bound to ΔTat and Tat++ IMVs. (A–C) Shown here is the quenching of various BODIPY-tagged pre-SufI mutants bound to IMVs in the absence of Tat translocons (ΔTat) by (A) 3-carboxy-PROXYL (3-CP), (B) 5-DOXYL stearic acid (5-D), and (C) 16-DOXYL stearic acid (16-D). Data were fit to Eq. 2 (Materials and Methods), which assumes a single fluorescent species (lipid-bound pre-SufI) and dynamic quenching. The slope of each line yields KD,L. (D–F) Same as (A–C), except in the presence of overproduced TatABC (Tat++). Data were fit to Eq. 6, which assumes two fluorescent species (lipid- and translocon-bound pre-SufI) and dynamic quenching, using the KD,L values from (A), (B), and (C), respectively, and the average acceptable α-value (see text, Fig. S4; Materials and Methods). (G–I) Shown here are predicted quenching curves for the quenching of translocon-bound pre-SufI mutants by 3-CP, 5-D, and 16-D. Slopes are the average KD,T values (summarized in Fig. 3) obtained from the fits in (D–F), respectively, which were estimated from the KD,T values obtained using the two extreme acceptable α-values. The mutants shown and the color-coding is the same in all panels. For clarity, error bars are not shown, but were typically ∼2–10% (N = 3, except for the V21C mutant, for which N = 6 for all three quenchers for the Tat++ conditions).

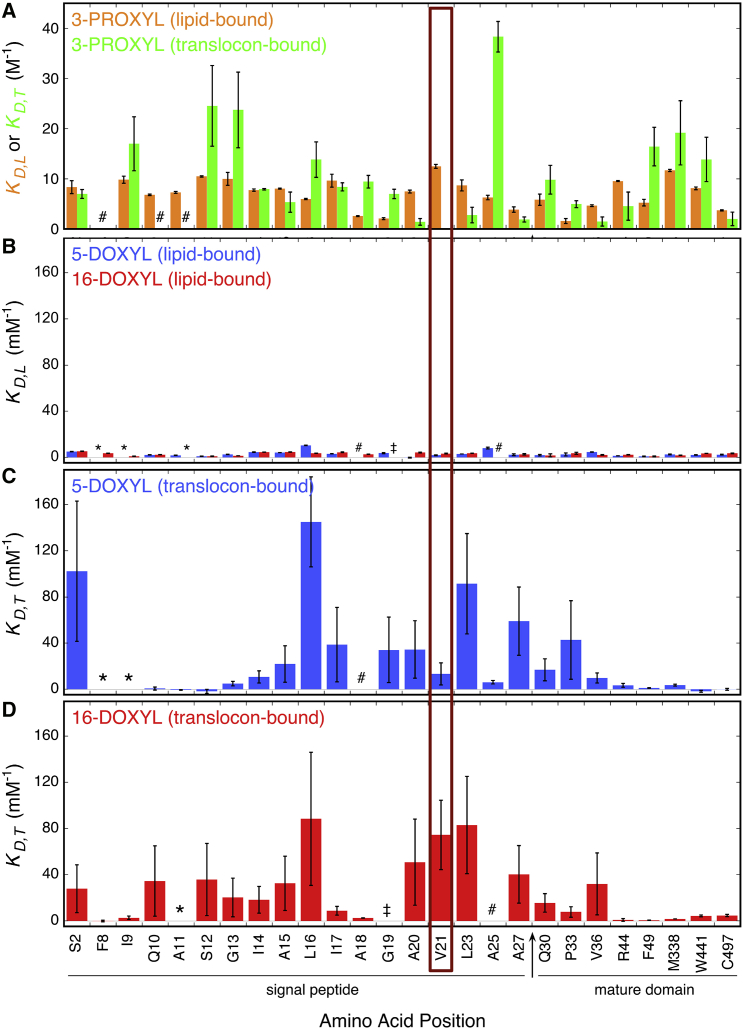

Figure 3.

Hairpin insertion of the pre-SufI signal peptide. (A–D) Shown here are quenching constants (KD,L and KD,T) for BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI single cysteine mutants, as indicated. The increase in quenching by the DOXYL stearic acids in the presence of TatABC for signal peptide residues (compare (C and D) with (B)) indicates insertion of the signal peptide into the membrane. These data indicate that the point of deepest penetration is near V21 (maroon box). For some mutant-quencher combinations, the KD determinations were considered unreliable or did not fit the simple models described by Eqs. 2 and 6. These situations are indicated as ∗, #, or ‡ and are discussed in Materials and Methods. For KD,L values, errors are the standard error of the mean. For KD,T values, error bar limits were determined by the limiting acceptable α-values (see Materials and Methods; Fig. S4). This is a highly conservative method of determining error, which would typically be substantially smaller if translocon binding affinities were assumed not to vary for the different dye-labeled pre-SufI mutants (i.e., if α was constrained; see text for additional discussion). The KD values for 5-D and 16-D are two-to-three orders of magnitude smaller than those for 3-CP because the stearic acids strongly partition into the membrane bilayer, which increases their local concentration (57).

For some mutant-quencher combinations, three distinct constants (KD,L, KD,T, and α) were indeed required to fit the quenching data obtained in the presence of TatABC, as predicted by Eq. 6. However, an approximately linear relationship was often obtained under Tat++ conditions, which is consistent with the condition that KD,L ≈ KD,T. Under these circumstances, α was poorly constrained by the data. The range for α was assumed to be 0.1–0.9, unless otherwise constrained by the data. This large range is conservative, leading to relatively high errors in KD,T values, but reasonable because all α-values constrained by quenching data were within this range (Fig. S4), all BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI mutants bound to the ΔTat membranes (Fig. S3 B), and all mutants were transport-competent (Fig. S3 A), and hence bind to the TatBC complex. The α-value is constrained by the data in two ways: first, by fitting according to Eq. 6; and second, by the quenching observed under ΔTat and Tat++ conditions. For this latter situation, assume a, b, and c are the total quenching observed (F0/F) under ΔTat, Tat++, and translocon-bound only conditions (a < b < c). Then, F/F0 = 1/b under Tat++ conditions is given by

| (7) |

Solving for 1 – α (the lipid-bound fraction) yields

| (8) |

implying that α > 1 – a/b. For a > b > c, the lower limit for α occurs when c = 1, leading to α ≥ (b – a)/b(1 – a). For a = b (implying that a = c), α could be any value from 0 to 1.

For some mutant-quencher combinations, the KD determinations were considered unreliable or did not fit the simple model discussed in this section, and were therefore eliminated from further evaluation. These situations are indicated as ∗, #, or ‡ in Fig. 3. In three cases (∗), KD,L values were <−2 mM, indicating enhancement of fluorescence, which was not expected. In five cases (#), upward or downward curvature (the latter under ΔTat conditions only) was observed, suggesting one or more quencher binding sites, or multiple environments of the fluorophore. In 1 case (‡), KD,T was extremely poorly constrained by varying α over a narrow range.

Analysis

All of the data presented here represent a mean of at least three experiments and the error bars are the SE of the mean, unless otherwise indicated. Quenching constants were obtained by using the software KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Paramus, NJ) to fit the quenching data to Eqs. 2 or 6.

Results

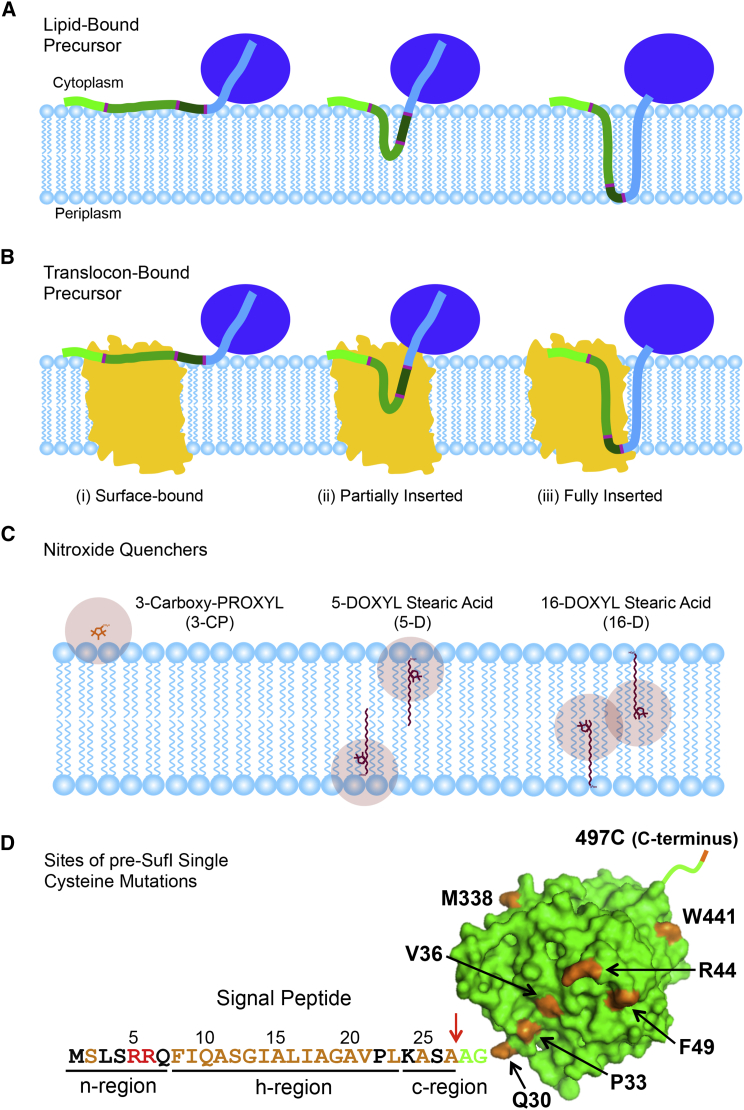

Fluorescence quenching approach to probe lipid and aqueous accessibility

To probe the environment and penetration depth of the Tat signal peptide during the initial stages of transport (Fig. 1, A and B), we used nitroxide quenchers to determine the relative accessibility of a BODIPY-FL fluorescent probe (Fig. S1) attached to different single cysteine mutants of pre-SufI, a natural Tat substrate. Nitroxide quenchers have a quenching distance of ∼10–12 Å—it is typically assumed that fluorescence quenching occurs if the nitroxide approaches within this distance to the probe, and that quenching does not occur if the distance of closest approach is larger than this cutoff (55). 3-Carboxy-PROXYL (3-CP) (Fig. S1) is a water-soluble, membrane-impermeant nitroxide (56) that was used to determine if the BODIPY-FL probe was accessible from the cis-aqueous phase (Fig. 1 C). 5-DOXYL and 16-DOXYL stearic acids (5-D and 16-D) (Fig. S1) have nitroxides at the indicated positions on the 18-carbon saturated fatty acid. When added from aqueous stock solutions, fatty acids rapidly partition into both leaflets of lipid bilayers with their carboxylate headgroup at the aqueous-lipid interface and their hydrocarbon tail aligned with the lipid tails. Thus, guided by a previous study (57), we assumed that the fluorescence of a probe positioned near the middle of the membrane bilayer would be better quenched by 16-D than 5-D (see Fig. S2) and that the fluorescence of a probe that shallowly penetrates the membrane would be strongly quenched by 5-D and moderately quenched by 3-CP and 16-D (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

Experimental strategy of the fluorescence quenching experiments. (A and B) Shown here are three possible modes of signal peptide interaction with both the lipids (A) and the Tat translocon (B). The light, medium and dark green colors denote the n-, h-, and c-regions of the signal peptide, respectively (N-terminal, hydrophobic, and C-terminal regions). Dark blue represents the folded mature domain, and light blue represents a portion of the mature domain that can potentially unravel allowing the majority of the mature domain to remain folded (see later). An outline of an E. coli model of the TatC structure is shown in yellow (SWISS-MODEL: P69423) (12). (C) Shown here is the approximate membrane penetration depth of the three nitroxide quenchers used in this study and their approximate quenching radii (∼10–12 Å) relative to the membrane bilayer. 3-Carboxy PROXYL is membrane-impermeant, and the DOXYL stearic acids rapidly flip-flop between the two leaflets of the bilayer (55). (D) Shown here are locations in pre-SufI used to create single cysteine mutations. The three signal peptide regions and the pre-SufI mature domain (green; PDB: 2UXV) are identified. The 26 amino acids individually replaced with cysteine are identified in orange, the RR-motif is identified in red, and the signal peptidase I cleavage site is indicated by a red arrow.

Twenty-six different single cysteine pre-SufI mutants were generated (Fig. 1 D). In all cases, single cysteine mutants were labeled with BODIPY-FL maleimide. The fluorescence emission of BODIPL-FL is insensitive to environment hydrophobicity (58, 59). The C-terminal cysteine mutant, pre-SufI(497C), served as our wild-type (wt) reference because a C-terminal dye does not affect transport efficiency (36). Transport efficiencies for most BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI mutants were ∼80–120% of wt (Fig. S2 A), indicating a minimal effect of the probe on transport for most labeled proteins. Notable exceptions were the F8C and I9C mutants for which transport efficiencies were reduced to ∼20% and ∼50% of wt, likely because these sites are near the RR-motif (see Fig. 1 D).

Hairpin insertion of the signal peptide

Representative plots for the concentration-dependent quenching of the fluorescence of BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI mutants bound to IMVs by 3-CP, 5-D, and 16-D are shown in Fig. 2. Although all 26 BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI mutants were analyzed with all three nitroxide quenchers in the presence and absence of TatABC, nine mutant-quencher combinations proved difficult to evaluate (see Materials and Methods) and were removed from the summary and analysis described below, which disregards these unusual situations. All of our binding experiments with BODIPY-labeled pre-SufI mutants were done in the absence of NADH (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4), and thus, the mature domain remained on the cytosolic side of the membrane.

Figure 4.

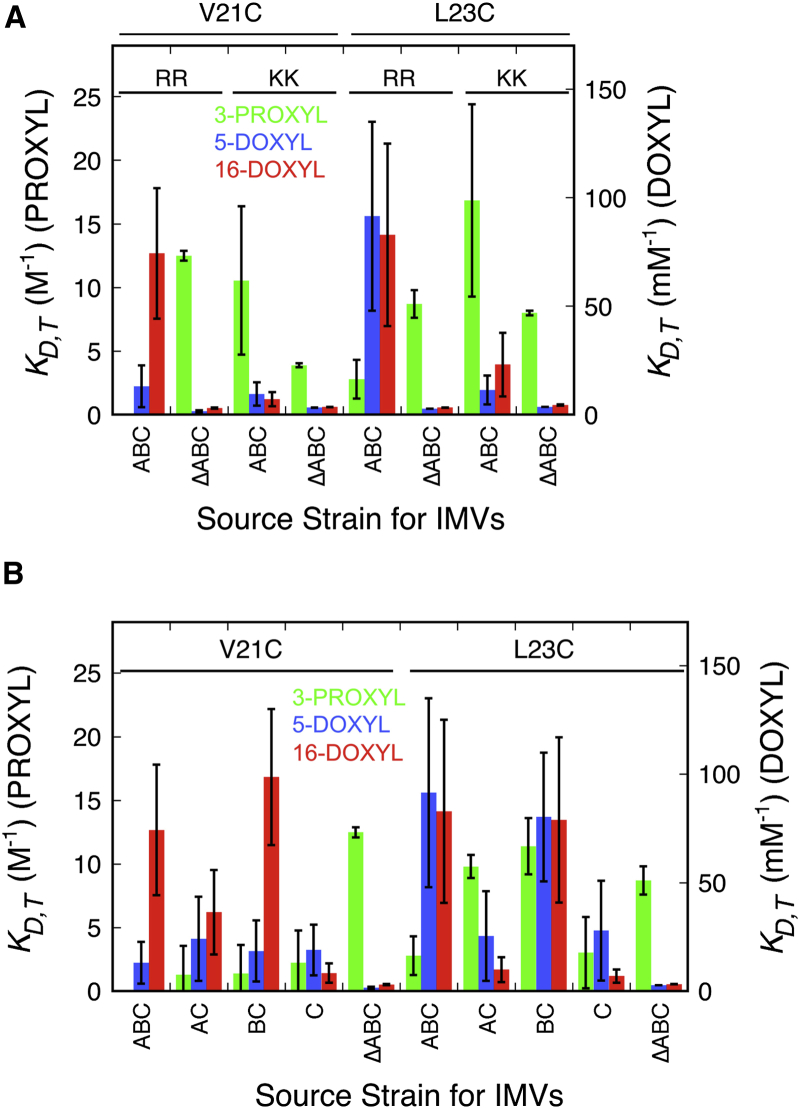

Pre-SufI signal peptide insertion requires the RR-motif, TatB, and TatC. (A) Signal peptide insertion requires the RR-motif. The membrane-inserted nitroxide quenching signatures observed for the V21C and L23C BODIPY-tagged pre-SufI mutants under Tat++ conditions (ABC) were lost when the RR-motif was replaced by KK. Instead, the observed signature resembles the lipid-bound signature obtained under ΔTat (ΔABC) conditions. (B) Signal peptide insertion requires TatB and TatC. The nitroxide quenching signatures for the V21C and L23C BODIPY-tagged pre-SufI mutants were examined in the presence of various combinations of overproduced TatA, TatB, and TatC. The DOXYL quenching diagnostic for membrane insertion required TatB and TatC. However, full protection from 3-CP for the L23C mutant also required TatA.

In the absence of Tat translocons (ΔTat), the amount of quenching was linearly dependent upon the quencher concentration (typical Stern-Volmer quenching; Fig. 2, A–C). In the presence of overproduced TatABC (Tat++), the fluorescence quenching sometimes yielded a concave-down quadratic dependence on quencher concentration (Fig. 2, D–F), suggesting the presence of multiple fluorescent species with significantly different quenching constants (54). This interpretation is consistent with our earlier finding that the pre-SufI precursor protein binds to both the lipid surface and the Tat translocon (36). Although static and dynamic quenching are each possible for both the lipid- and translocon-bound precursor proteins, only a single quenching constant was necessary for each of the two species to fit the quenching data, which were assumed to be the dynamic quenching constants KD,L and KD,T for the lipid-bound (L) and translocon-bound (T) precursor proteins, respectively (see Materials and Methods). The ΔTat data were analyzed first to obtain KD,L using Eq. 2, which assumes that the translocon-bound fraction (α) is zero. Using this KD,L value, we then estimated KD,T and α from the Tat++ data using Eq. 6. The corrected translocon-bound quenching curves (the prediction if all IMV-bound pre-SufI was bound to Tat translocons) are shown in Fig. 2, G–I. The corrected data are all linear because slope = KD,T at the average acceptable α-value. The quenching constants and the range of acceptable α-values obtained using this approach are summarized in Figs. 3 and S4, respectively. Note that each labeled pre-SufI mutant can reasonably be expected to have small differences in binding affinity for the TatBC complex due to the position of the BODIPY dye in the signal peptide. Small differences in affinities are not expected to influence our general conclusions. More importantly, however, the described approach specifically corrects for differences in translocon binding affinity.

The quenching constants obtained for the different pre-SufI mutants bound to the lipid or to Tat translocons revealed a strikingly different accessibility profile for the signal peptide under these two conditions. When pre-SufI was bound to membranes without Tat translocons, the fluorescence of the dye attached to all signal peptide mutants was largely unquenched by 5-D or 16-D (Fig. 3 B). In most cases, a moderate quenching was observed with 3-CP (Fig. 3 A, orange). Because the signal peptide mediates membrane binding of pre-SufI (36), these quenching data indicate that the signal peptide binds in the aqueous-lipid interfacial region, and that it does not significantly penetrate the membrane in the absence of Tat translocons (e.g., as in Fig. 1 A(i)). In contrast, it was concluded that a plant Tat precursor protein fully inserts its signal peptide into the membrane in the absence of any Tat proteins (38, 40). In the presence of Tat translocons, there was a substantial increase in 5-D and 16-D accessibility to the BODIPY-FL dye attached to signal peptide residues downstream of the RR-motif. As a striking example, when TatABC was present, the V21C attached dye was inaccessible to 3-CP and 5-D, and substantially quenched by 16-D (Fig. 3 A (green), Fig. 3, C and D). Overall, numerous dye-labeled residues within the signal peptide displayed a substantially increased quenching by the DOXYL stearic acids in the presence of Tat translocons. In contrast, the dye attached to surface-exposed residues of the mature domain far from the signal peptide (residues ≥ 44) was not accessible to the lipid quenchers. The simplest interpretation is that the signal peptide was inserted into the membrane by the Tat proteins and that the region around V21C was positioned near the center of the membrane bilayer (e.g., as a hairpin such as that depicted in Fig. 1 B(ii) or (iii)).

As discussed in the last paragraph, the nitroxide quenching data were interpreted from a global perspective rather than trying to decipher the reasons behind individual quenching constants. There are multiple reasons why a smooth trend was likely not observed for the quenching constants as the dye probe was moved within the signal peptide: the fluorophore-nitroxide quenching distance of ∼10–12 Å (which defines the resolution of the fluorescence method), the ∼14 Å tether length between the cysteine and the fluorescent probe (i.e., the probe could be a significant distance from its attachment site), the exact position/orientation of the fluorescent probe with respect to the signal peptide, and the likely possibility that the probe at each position is differentially protected from the quenchers by the Tat proteins. Together, these factors likely led to variability in the position of the probe relative to its attachment site and its accessibility to the nitroxide quenchers, which in turn likely led to the large changes in quenching constants as the probe was moved in small steps along the signal peptide. Nonetheless, there is a striking global difference in probe accessibility in the absence and presence of Tat translocons (compare Fig. 3 B with Fig. 3, C and D).

Signal peptide insertion requires TatB, TatC, and a functional signal peptide

We next tested the minimal essential protein requirements for hairpin insertion of the signal peptide. Previous work indicated that mutation of the RR-motif to KK blocks Tat transport (14) and results in loss of binding to the Tat translocon (36). Using our nitroxide quenching approach, we examined the effect of this KK mutation on the signal peptide insertion process using the V21C and L23C pre-SufI mutants, both of which yielded strong insertion signatures for all three nitroxide quenchers. For both the KK-V21C and KK-L23C mutants under Tat++ conditions, 16-D quenching was largely eliminated and 3-CP quenching was strongly enhanced by the KK mutation (Fig. 4 A), indicating that recognition of the RR-motif by the Tat translocon is required for membrane insertion. We then selectively eliminated Tat proteins from the IMVs. The nitroxide quenching constants obtained for the V21C and L23C pre-SufI mutants indicate that the signal peptide insertion signatures were produced for 5-D and 16-D in the absence of TatA with only TatC and TatB present (Fig. 4 B). This is consistent with multiple previous studies that have identified a complex of TatC and TatB as the initial receptor complex for Tat precursor proteins (13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 60). However, full protection from 3-CP for the L23C mutant additionally required TatA (Fig. 4 B), agreeing with previous reports that indicate the presence of TatA in the receptor complex (20, 26, 60, 61).

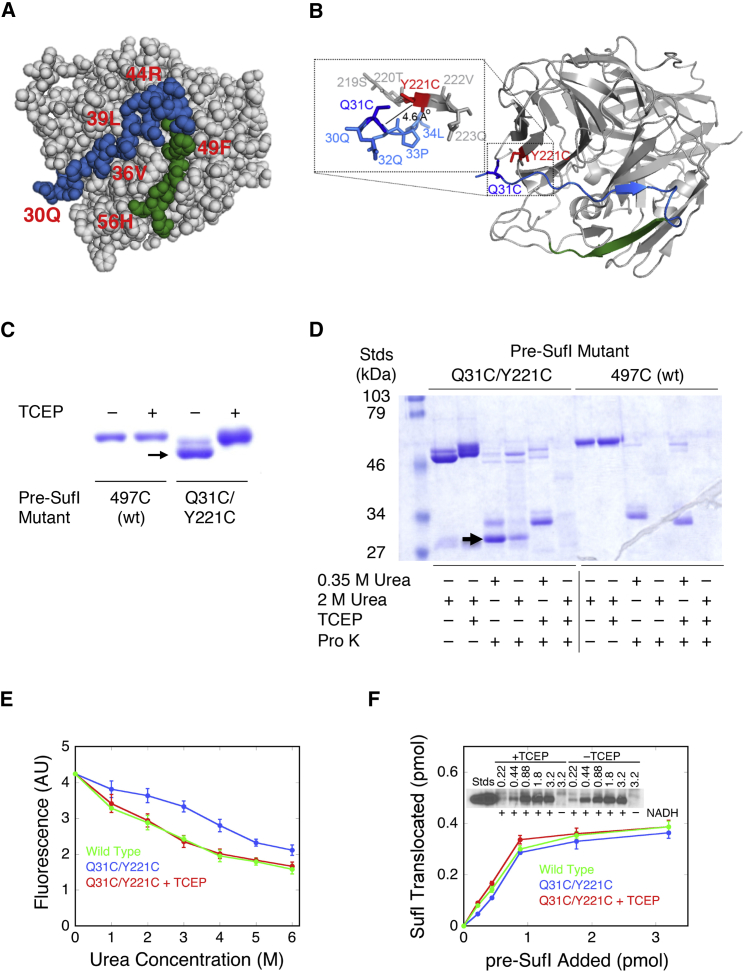

The translocon-bound signal peptide hairpin of pre-SufI penetrates partway across the membrane bilayer

A hairpin loop that fully penetrates the membrane bilayer crosses the membrane midplane twice (see Fig. 1 B(iii)), and therefore, there could be two locations in pre-SufI where an attached dye molecule could be strongly quenched by 16-D and not by 5-D or 3-CP. We only observed one such location (V21C) in our quenching experiments (Fig. 3). Ultimately, the N-terminal end of the signal peptide (likely including the RR-motif) remains on the cis (cytoplasmic) side of the membrane (43, 62), whereas the signal peptide cleavage site must reach the trans (periplasmic) side of the membrane, allowing signal peptidase I to release the signal peptide from the mature domain (43, 63, 64, 65). The folded mature domain of pre-SufI begins at residue 30, and the signal peptide cleavage site is between residues 27 and 28. Therefore, for a model of the precursor-receptor complex in which the pre-SufI signal peptide cleavage site fully crosses the membrane whereas the mature domain remains on the cis side of the membrane, the mature domain must partially unfold (Figs. 1 A(iii) and B(iii) and 5 A). To test this possibility, the double cysteine mutant pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) was generated. Q31 and Y221 are close enough to form a disulfide after mutation to cysteines. This disulfide was expected to block/reduce unfolding of the mature region (Fig. 5 B). The presence of an internal disulfide cross-link in pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) was assessed by SDS-PAGE mobility shift, protease susceptibility, and denaturant-dependent tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 5, C–E). A large fraction (∼80%) of the as-isolated form of this double cysteine mutant protein migrated faster than its reduced form or the single cysteine mutant pre-SufI(497C), suggesting the presence of an internal disulfide cross-link (Fig. 5 C). This as-isolated protein was more resistant to protease and urea denaturation than wild-type pre-SufI (Fig. 5, D and E). These data support the hypothesis that the presence of a disulfide bond between residues 31 and 221 of pre-SufI enhanced the stability of the folded mature domain. Addition of TCEP, a disulfide-reducing agent, had essentially no effect on transport efficiency even in the linear portion of the saturation curve (<1 pmol pre-SufI; Fig. 5 F), indicating that the reduced and the internally cross-linked forms of pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) transport with similar efficiencies. In total, these data strongly support the hypothesis that mature domain unfolding does not occur during pre-SufI transport. Consequently, these data support a model in which the signal peptide cleavage site has not migrated across the membrane in the initial receptor-precursor complex. Unless the signal peptide binds to the Tat receptor complex in a fully extended conformation, the length of the signal peptide hydrophobic domain is insufficient to cross the membrane bilayer twice. Instead, the propensity of h-domains of Tat signal peptides to adopt helical structures (see later Discussion) (37) suggest that the translocon-bound signal peptide hairpin of pre-SufI penetrates only partway, not completely, across the membrane bilayer (i.e., as in Fig. 1 B(ii) but not as in Fig. 1 B(iii)).

Figure 5.

The pre-SufI mature domain remains folded during transport. (A) Shown here are surface-exposed residues of the SufI mature domain (PDB: 2UXV) immediately downstream of the signal peptide cleavage site. Residues 30–47 (blue) and 47–55 (green) could potentially unravel to allow full signal peptide insertion (Fig. 1, A(iii) and B(iii)) whereas the rest of the mature domain could remain folded. The signal peptide cleavage site between residues 27 and 28 was not recovered in the structure. (B) Shown here is the structural proximity of the cysteines in the pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) double mutant. Residues Q31 (dark blue) and Y221 (red) are close enough (Cα-Cα ≈ 6.2 Å; Cβ-Cβ ≈ 4.6 Å) to generate a disulfide after mutation of both to cysteine. (C) Shown here is the disulfide in the purified pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) double mutant. On an SDS-PAGE gel, the as-isolated protein was detected as two bands, which coalesced into one band when reduced with TCEP (1 mM). As the upper/reduced band migrated similarly to the single cysteine pre-SufI(497C) (wt) protein, the lower band was assumed to be internally cross-linked protein (arrow; ∼80% of the total protein). (D) Shown here is the protease resistance of disulfide cross-linked pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C). The as-isolated wt and pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) proteins were incubated with proteinase K (Pro K, 10 μg/mL) at room temperature for 30 min in the presence of low (0.35 M) or high (2 M) urea concentrations. A protease-resistant band (arrow) was observed under low urea and no TCEP conditions only for pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C). (E) Shown here is the structural stability of disulfide cross-linked pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C). Tryptophan fluorescence of wt pre-SufI decreased at higher urea concentrations, consistent with denaturation. The TCEP-reduced pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) protein behaved similar to wt. However, the fluorescence of the as-isolated pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C) protein was less sensitive to urea concentration, consistent with an increased stability of the disulfide cross-linked protein. (F) Shown here is the in vitro Tat transport efficiency of disulfide cross-linked pre-SufI(Q31C/Y221C). Transport was unaffected by the presence (blue) or absence (red) of a disulfide cross-link. Transport conditions were as in Fig. S3A.

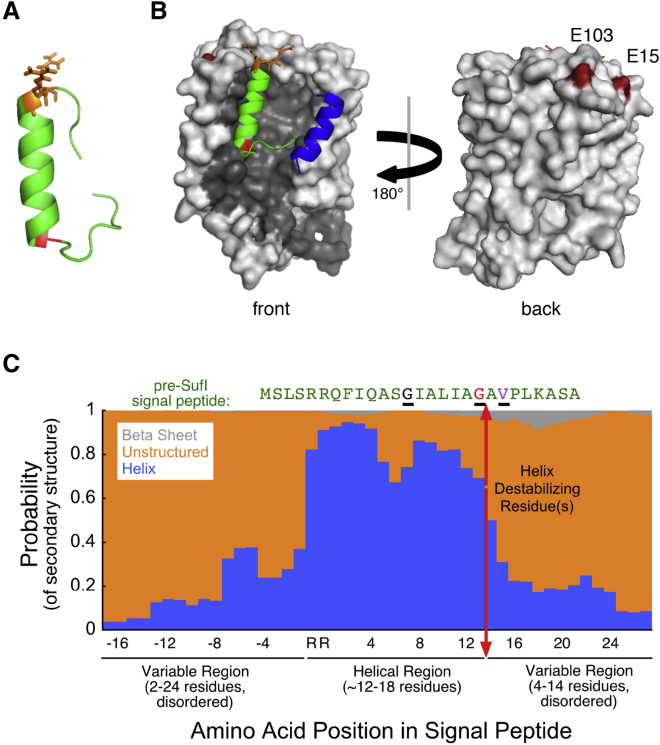

Structural modeling of TatBC-signal peptide interactions

To establish a structural framework for understanding the implications of a translocon-bound signal peptide hairpin and to investigate whether partial membrane penetration of a signal peptide hairpin is generally feasible for Tat substrates, we used a predictive/computational approach to probe signal peptide structural propensities and model their interactions with the TatBC complex. For the pre-SufI signal peptide, PEP-FOLD (48) predicted a short helix (∼21 Å), beginning after the RR-motif followed by a C-terminal disordered region (Fig. 6 A). Using the ZDOCK docking algorithm (52), this unaltered signal peptide structure was readily accommodated inside the transmembrane groove on the side of TatC with its C-terminal region positioned near the known TatB binding region (Fig. 6 B), suggesting that the inherent structural propensity of the signal peptide is designed to be recognized by the receptor complex with minimal perturbations. To explore whether this design might be a general feature, signal peptide structures were predicted for 25 E. coli Tat substrates (Fig. S5). Notably, although the length of the helix immediately following the RR-motif varied considerably, the C-terminal end of the helix was typically followed by a glycine (80%), a known helix-destabilizing residue (66). Helix termination is necessary for generating a hairpin. Although the position of this glycine residue was variable, it was commonly found 12–17 residues away from the RR-motif (Fig. S6). Four representative signal peptide structures were docked into the TatBC receptor complex (Fig. S7). Extending our analysis, JPred (50) was used to predict the secondary structural propensities of 512 bacterial Tat signal peptides, including both predicted and experimentally verified Tat substrates. This analysis revealed a strong preference for a helical region following the RR-motif (Fig. 6 C), followed by a strong preference for a glycine residue (Fig. S8). Generalizing, our analysis suggested that Tat signal peptides are organized with five structural features (in order): 1) a disordered region of variable length; 2) the RR-motif; 3) a helical structure (typically ∼12–17 amino acids); 4) one or more helix destabilizing residues (usually glycine—see Discussion); and 5) a second disordered region of variable length (Fig. 6 C). These design similarities suggest that a single binding pocket could accommodate the diversity of Tat signal sequences.

Figure 6.

Secondary structure of Tat signal peptides. (A) Shown here is the predicted secondary structure of the pre-SufI signal peptide (residues 1–27). The PEP-FOLD peptide structure prediction algorithm (48) yielded an h-region helix connected to an unstructured C-terminal region by a glycine (G) helix-breaking residue (red). The RR-motif (orange) is found at the N-terminal end of the helix. (B) Shown here is the pre-SufI signal peptide docked into the TatBC complex. Using ZDOCK (52), the TatB membrane domain (blue; residues L7-G21) was first positioned onto the TatC structure (gray; SWISS-MODEL: P69423) based on previous data indicating interactions with TM5 of TatC (12, 26). The pre-SufI signal peptide structure from (A) was then docked into this TatBC complex (lowest energy interaction) without any conformational relaxation of the Tat proteins or the signal peptide. The resultant signal peptide/receptor complex structure is consistent with the hairpin insertion by the TatBC complex. The RR-motif is near the two glutamic acid residues (dark red; E15 and E103) at the top of TatC involved in binding this motif, the tip of the hairpin is near the center of the bilayer, and the C-terminal end of the signal peptide is near TatB (see later cross-linking studies and the Discussion). (C) Shown here is the predicted secondary structures for 512 Tat signal sequences. The JPred structural propensity algorithm (50) predicts that the RR-motif and h-domain are largely helical, and that this central region of Tat signal peptides is flanked by unstructured domains. One or more helix-destabilizing residues (see text) at the C-terminal end of the h-domain helix is consistent with the bend necessary to form a hairpin. Note that some signal peptides have one or more helix-destabilizing residues within the h-domain (e.g., G13 of pre-SufI; black) before the helix-destabilizing residue(s) at the end of the helical domain (e.g., G19 of pre-SufI; red) (see also Fig. S6). V21, which deeply penetrates the membrane (Fig. 3) when the pre-SufI signal peptide is bound to TatBC, is identified in purple. Black underlines help to identify these three residues in the pre-SufI sequence.

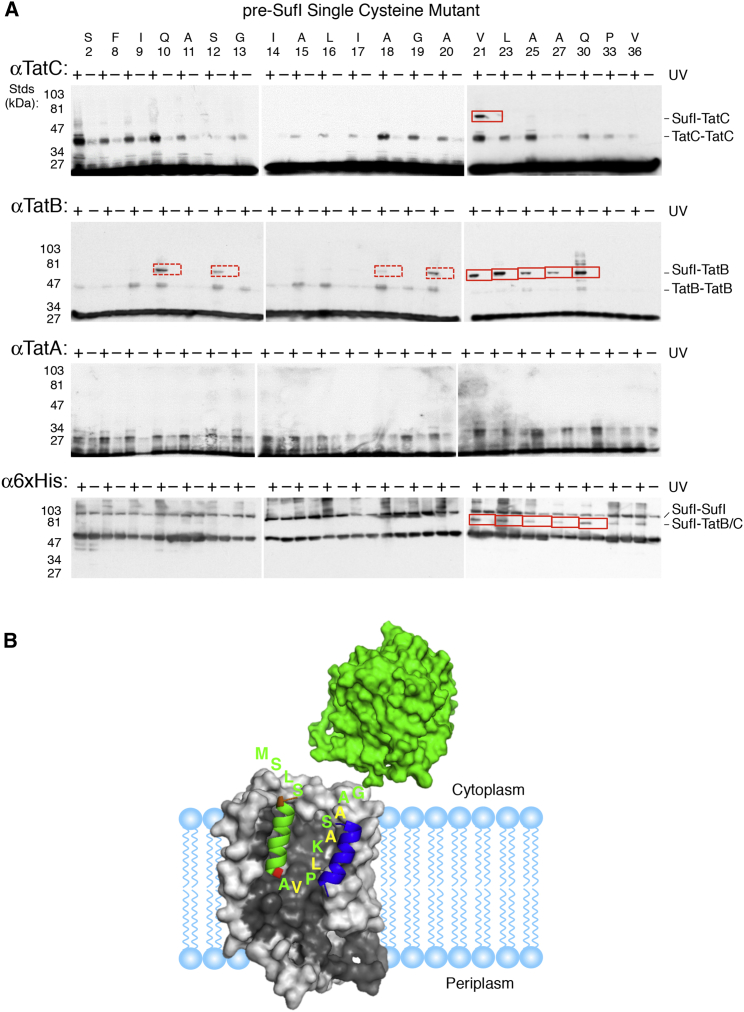

Signal peptide binding interactions with the TatBC complex

Fluorescence quenching data revealed that membrane insertion of the signal peptide requires both TatB and TatC (Fig. 4). To more precisely probe the interactions of the signal peptide hairpin structure with the TatBC complex, we turned to photocross-linking. Single cysteine mutants of pre-SufI were labeled with 4-(maleimido)benzophenone (Fig. S1), which has a linker length of ∼9–11 Å (67), and photo-cross-linking was induced by UV illumination after incubating the benzophenone derivatives of pre-SufI with Tat++ IMVs. TatB was the most frequently cross-linked translocon protein, yielding an adduct of ∼80 kDa. Out of 18 signal peptide mutants, major cross-links (detected in 100% of attempts) to TatB were observed when the photocross-linker was attached at positions V21, L23, A25, and A27 of pre-SufI. A major cross-link between the SufI mature domain (Q30) and TatB was also observed. A major cross-link to TatC (also an adduct of ∼80 kDa) was only observed for the V21 mutant. Cross-links to TatA were not observed. The major TatB and TatC cross-linked products were also observed on a 6×His immunoblot, which probes for SufI (Fig. 7 A). These data suggest that the C-terminal half of the signal peptide hairpin contacts TatB, and that the hinge region (near V21) contacts both TatB and TatC (Fig. 7 B).

Figure 7.

Photocross-linking of pre-SufI single cysteine mutants with Tat components. (A) Shown here is cross-linking of pre-SufI with TatABC. The indicated single cysteine mutants of pre-SufI were modified with 4-(maleimido)benzophenone, incubated with Tat++ IMVs, and irradiated with UV light for 5 min. Membrane-bound pre-SufI was recovered by centrifugation (16,200 × g, 30 min). The samples were resolved via SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with TatA, TatB, TatC, and 6×His antibodies as indicated. Pre-SufI-TatB and pre-SufI-TatC adducts are both ∼80 kDa. Major (solid red box) and occasional (dashed red box) cross-links were observed in 100% and <50% of reactions, respectively (N ≥ 3). (B) Shown here is a cartoon of the interaction of the C-terminal half of the pre-SufI signal peptide hairpin with TatB. Highlighted residues (yellow) strongly cross-link to TatB (blue), as shown in (A). The helical domain of the signal peptide is colored as in Fig. 6A, and its interaction with the TatC structure (gray) is reproduced from Fig. 6 B. The globular pre-SufI mature domain (green; PDB: 2UXV) remains cytoplasmic when bound to TatBC in the absence of a pmf.

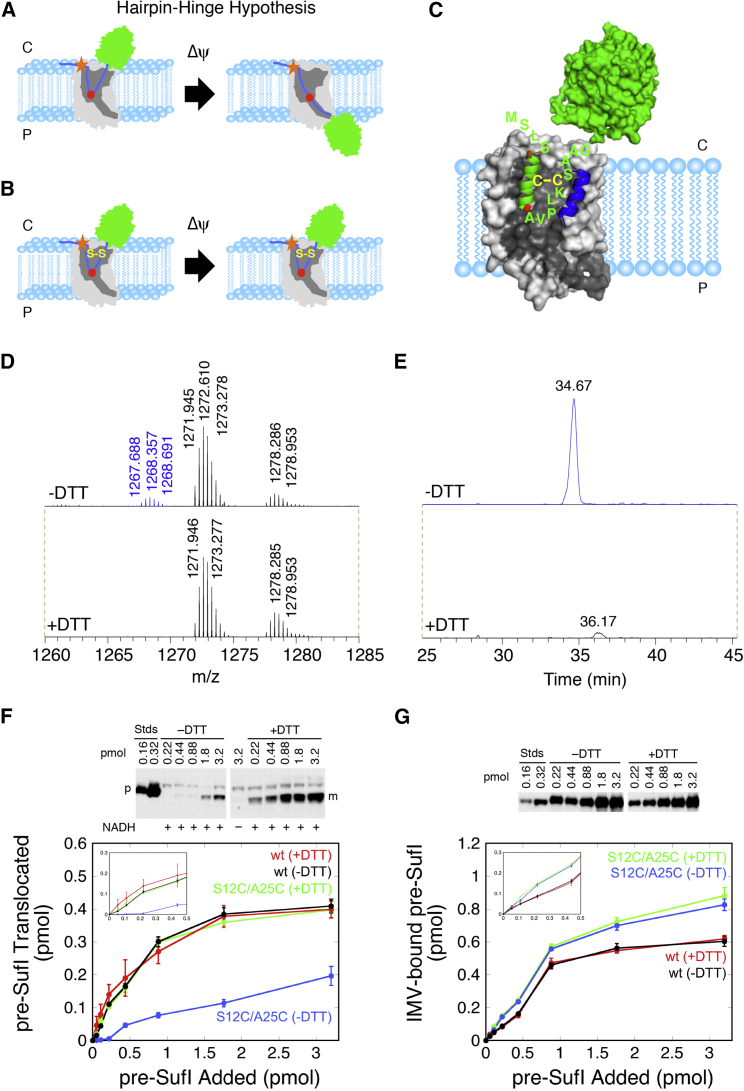

Hairpin-hinge hypothesis

The data discussed thus far strongly suggest that a signal peptide hairpin of pre-SufI is inserted into the membrane by the TatBC receptor complex and reaches about halfway across the membrane. During the translocation process, the mature domain and the C-terminal end of the signal peptide must migrate across the membrane, whereupon the signal peptide is cleaved from the precursor protein in the periplasm by the LepB protease (signal peptidase I) (43, 63, 64, 65). How can this translocation process occur while maintaining the signal peptide binding interaction? Flexibility at the point of deepest penetration of the signal peptide hairpin was suggested by the helix-destabilizing residue(s), typically glycine, discussed in Structural Modeling of TatBC-Signal Peptide Interactions. Therefore, we hypothesized that unhinging of the signal peptide hairpin would allow mature domain translocation while the N-terminal half of the signal peptide remained anchored within its binding/recognition site (Fig. 8 A). To test this hairpin-hinge hypothesis, we introduced cysteines at S12 and A25 in the signal peptide of pre-SufI, anticipating that a disulfide cross-link between these two positions would block transport (Figs. 8, B and C). Mass spectrometry analysis established that a fraction (∼10–15%) of the as-isolated pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) protein was disulfide cross-linked (Figs. 8, D and E; Fig. S9 A). In vitro Tat transport assays with an enriched preparation of the disulfide-linked pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) protein revealed that DTT significantly enhanced transport yield, particularly at lower precursor concentrations (by ∼3–5-fold; Fig. 8 F). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the cross-linked protein cannot be transported (or is transported substantially less efficiently than the uncross-linked protein). Importantly, the internal disulfide did not reduce membrane and translocon binding efficiency (Fig. 8 G; Fig. S10), indicating that the cross-link does not interfere with binding to the TatBC complex, as expected (Fig. 8 C), although the cross-linked protein may not bind to the TatBC complex in the same conformation as the un-cross-linked protein. Cross-linking of the V21C mutant to TatC blocked pre-SufI transport (Fig. S11), consistent with the hypothesis that signal peptide residues after the hinge residue (G19) must move during transport. These data strongly support a model in which a conformational change in the signal peptide is required during transport, consistent with the hairpin-hinge hypothesis (Fig. 8 A).

Figure 8.

Testing the hairpin-hinge hypothesis with an internally cross-linked signal peptide. (A) Shown here is the hairpin-hinge hypothesis. During translocation of the mature domain (green) from the cytoplasm (C) to the periplasm (P), the hairpin formed by the signal peptide (blue) is hypothesized to open via a hinge (high flexibility) region (red) at the tip of the hairpin. The position of the RR-motif is indicated (orange star). (B) Shown here is how a disulfide can block unhinging of the signal peptide hairpin. According to the hairpin-hinge hypothesis, an internally disulfide-cross-linked signal peptide hairpin cannot unhinge under energized conditions, thus blocking translocation. Binding is predicted to be unaffected (compare with (A)). (C) Shown here is the predicted interaction of the oxidized double-cysteine mutant pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) with the TatBC complex (compare with Fig. 7B). (D) Shown here is liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of trypsin-digested as-isolated pre-SufI(S12C/A25C). The peak centered at m/z = 1268.357 is consistent with a +3H ion consisting of two peptides (amino acids 12–24 and 25–43) linked by a disulfide bond between S12C and A25C. Trypsin digests peptides after lysine and arginine residues—in particular, digesting pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) after R11, K24, and R43. Under +DTT conditions, the m/z = 1268.357 peak was substantially diminished, consistent with reduction of the disulfide. Other peaks were unchanged and used for calibration. CID analysis confirmed the identity of the two indicated peptides (Fig. S9A). (E) Shown here is extracted ion chromatography of the disulfide-linked peptide identified in (D). The ion intensity was reduced by ∼97% under +DTT conditions. (F) Shown here is the transport yield of pre-SufI(S12C/A25C). After enriching the disulfide-linked form of pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) to ∼60% (see Materials and Methods; Fig. S9B), transport assays with Tat++ IMVs were performed over a range of initial precursor concentrations. In the presence of DTT, pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) transported similarly to the pre-SufI(497C) (wt) protein. However, in the absence of DTT, pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) transport was substantially diminished. This effect was largest at lower precursor concentrations, suggesting that at higher concentrations more of the un-cross-linked protein is transported (p, precursor; m, mature). (G) Shown here is membrane-bound pre-SufI(S12C/A25C). The high amount of pre-SufI(S12C/A25C) bound to Tat++ IMVs in the presence and absence of DTT indicates that the lower transport yield observed under –DTT conditions in (F) cannot be explained by weaker membrane binding interactions. The disulfide cross-linked pre-SufI protein binds to Tat translocons with similar affinity as the wt protein (Fig. S10).

Discussion

This work focuses on the interactions of the Tat signal peptide with the membrane lipids and the Tat translocon, and how the conformational structure of the signal peptide changes during the translocation process. Our results revealed that: 1) in the absence of Tat proteins, the pre-SufI signal peptide binds to the phospholipid bilayer of IMVs, but does not penetrate significantly into the membrane; 2) the pre-SufI signal peptide is inserted into the membrane by the TatBC receptor complex, likely as a hairpin that extends approximately halfway across the membrane bilayer; 3) the C-terminal end of the pre-SufI signal peptide interacts extensively with TatB; 4) the C-terminal portion of the pre-SufI signal peptide undergoes a significant conformational change during translocation, consistent with an unhinging of the initial hairpin structure; and 5) the general structural propensities of Tat signal peptides are consistent with a hairpin-hinge hypothesis describing signal peptide interactions and conformational changes. We now expand on these conclusions, and discuss a number of important implications.

Because nitroxides have a quenching distance of ∼10–12 Å (55), the fluorescence emission of a probe buried within the precursor-receptor complex could still be quenched by nitroxides. A useful point of scale is that quenching can occur if the probe is located at most an α-helical diameter (∼12 Å) away from the nitroxide quencher. Thus, signal peptide binding within the center of a receptor oligomer, such as in models described earlier involving dimeric, trimeric, or tetrameric TatBC structures (16, 17, 18, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31), is formally consistent with the observed nitroxide quenching data. However, a protected signal peptide binding site seems inconsistent with the transport competence of lipid-bound precursor protein (36)—how can a lipid-bound signal peptide be transferred into the center of an oligomeric receptor complex without dissociating from the membrane? To us, the number of labeled positions yielding quenching suggests that direct exposure of the signal peptide to the lipid bilayer interior is more likely. A lipid-exposed binding pocket would be readily accessible to precursor bound to the membrane surface (34, 36, 38, 40, 68). Thus, we currently consider it more likely that the signal peptide binds to an outside surface of the receptor complex in contact with the membrane lipids. This conclusion does not rule out an oligomeric receptor complex, as long as the signal peptide binding site is on the periphery exposed to the membrane lipids. For example, an octomeric structure for the receptor complex, as suggested by multiple lines of evidence (13, 14, 22, 23, 27), could have lipid exposed signal peptide binding sites, particularly because electron microscopy provides evidence for binding of pre-SufI to the periphery of such a complex (27).

Our results generally agree with the current consensus on the identity and structural characteristics of the signal peptide binding site of the Tat receptor complex. There is general agreement that TatC and TatB form the core of the receptor complex (13, 14, 15), consistent with the results of our membrane insertion assay using various Tat deletion strains (Fig. 4). Our photocross-linking data (Fig. 7) indicate that L23, A25, A27, and Q30 of receptor-bound pre-SufI are near TatB while the hairpin bend region (V21) contacts both TatB and TatC. These data are consistent with previous results indicating that TatB interacts with the bound signal peptide (16, 17, 19) and with Cys-match cross-linking data demonstrating that the signal peptide interacts with L205 of E. coli TatC (V270 of cpTatC) (24). The latter result established an interaction of the signal peptide (seven residues from the cleavage site) about halfway across the membrane in the TatC transmembrane groove near TatB, which interacts with TM5 of TatC (12, 24, 26). In total, these data form the basis for our placement of the signal peptide hairpin within the large groove formed on the side of the TatBC complex (Fig. 7 B).

Although the majority of TatA assembles with the receptor-precursor complex in the presence of a pmf (15, 69), previous results differ over whether a fraction of TatA is a component of the receptor complex in unenergized membranes. Our membrane insertion assay revealed that the signal peptide insertion signature was not fully established without all three Tat proteins (TatABC). Nonetheless, this signature was mostly recovered with TatB and TatC only (Fig. 4 B, L23C mutant). The defect in the absence of TatA was a greater accessibility to 3-CP, suggesting greater aqueous accessibility within the signal peptide binding pocket. Hence, TatB and TatC may be sufficient to fully insert the signal peptide, but the pocket may be more open, consistent with the lower affinity observed in energized membranes without TatA (29). Such binding pocket differences may indeed be difficult to detect depending on the approach used, explaining why some investigators have concluded that the receptor complex is formed from TatB and TatC (18, 20, 70), whereas other have concluded that TatA must be a part of this complex (22, 26, 29, 60, 61, 71, 72).

Considering our structural model for signal peptide interactions with the TatBC receptor complex (Fig. 6 B), we were surprised by the paucity of cross-links to TatC (Fig. 7 A), particularly because previous investigators were more successful at obtaining such cross-links (16, 24, 25). However, Western blotting, as we used here, is less sensitive to detecting inefficiently formed cross-links than autoradiography, which was used in the previous studies. In addition, the photocross-linking efficiency of benzophenone toward the different amino acid side chains varies considerably, with hydrophobic side chains typically having moderate reactivity (73). Thus, photocross-linking efficiency to the hydrophobic TatBC pocket was expected to be moderate, at best. The size of the photocross-linking agent could certainly influence signal peptide interactions with the binding pocket, although we note that the BODIPY probe is actually a bit larger (Fig. S1) and it had little influence on transport, in most cases (Fig. S3 A). The signal peptide binding pocket must accommodate a diverse set of sequences, and therefore, it is unlikely that recognition occurs through a tight lock-and-key type of interaction. Consequently, a fair amount of flexibility in signal peptide interactions and orientation are likely, and thus, a bulky side chain (or attached probe) may simply cause the signal peptide to reorient in the pocket. Such reorientation, according to our model, would likely force the dye or photocross-linker to often be extended toward the lipids, rather than toward the receptor surface, resulting in ready accessibility to nitroxide quenchers, but reducing cross-linking probability.

It was concluded earlier that TatC alone catalyzes insertion of the signal peptide (18). According to this work, six additional residues in the pre-SufI signal sequence enabled the signal peptide cleavage site to reach the periplasmic side of the membrane where the signal peptide was removed by signal peptidase (18). The pre-SufI membrane insertion reported herein differs from the insertion of this extended signal sequence construct (pre-SufI-ss-ex) on three points. First, the nitroxide fluorescence quenching signature diagnostic for pre-SufI signal peptide insertion in the presence of TatABC was not observed with TatC alone (Fig. 4 B). Therefore, pre-SufI-ss-ex must interact differently with TatC than wild-type pre-SufI. Second, an internally cross-linked pre-SufI protein that cannot unfold to allow the signal peptide cleavage site to deeply insert into the membrane was fully transport-competent (Fig. 5). Thus, the TatBC complex inserts the signal sequence of pre-SufI about halfway across the membrane with the signal sequence cleavage site near the cytoplasmic face of the membrane. And third, an internal disulfide cross-link within the pre-SufI signal peptide was fully competent for binding to the Tat receptor complex (Fig. 8). This disulfide between residues 12 and 25 establishes the “register” of the hairpin, because the binding of pre-SufI was unaffected when the signal peptide was locked by this cross-link. These data further establish that the signal peptide cleavage site in the pre-SufI/receptor complex is near the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. Thus, if pre-SufI-ss-ex is indeed cleaved on the periplasmic side of the membrane, the six additional residues in its signal sequence do not simply allow a slightly deeper membrane penetration, but instead enable a substantially different interaction.

The presence of a helix-destabilizing glycine residue immediately after the helical N-terminal portion of the inserted pre-SufI hairpin suggested flexibility, leading to the proposal of a hinge near the tip of the signal peptide hairpin. This hinge hypothesis was tested by determining whether mature domain translocation could occur when the signal peptide was cross-linked to the receptor complex. As the hairpin-hinge hypothesis predicts, translocation did not occur when the V21 position, two residues after the postulated pre-SufI hinge glycine, was cross-linked to TatC (Fig. S11). These data establish that the hinge occurs before V21 of pre-SufI. These data are consistent with previous results that demonstrated no translocation when the signal peptide was cross-linked to Hcf106 (chloroplast TatB) in a region corresponding to the C-terminal half of a signal peptide hairpin (17). Moreover, the same report also demonstrated that transport occurred when the signal peptide was cross-linked to TatC near the RR-motif (17), consistent with the hairpin-hinge hypothesis (Fig. 8 A).

A bioinformatics approach was used to probe the generality of the hairpin-hinge translocation mechanism, and to predict common features in Tat signal peptides. Based on secondary structure predictions (Fig. S5) and observed frequencies and similarities over all 512 Tat signal peptides examined (Fig. 6 C; Fig. S8), we conclude that a signal peptide helical motif is typically disrupted ∼12–17 residues after the RR-motif by a single G (39%), S (4%), or P (5%) residue. In 46% of cases, more than one of these residues is present. G, S, and P are known helix-destabilizing residues (66, 74). Although in 6% of cases a G, S, or P was not found 12–17 residues following the RR-motif, such residues were frequently found earlier, suggesting flexibility earlier in the signal peptide. Secondary structure predictions are consistent with the hypothesis that, in some cases, the hinge may occur earlier, leading to a shorter signal peptide hairpin (Fig. S5). A shorter helix before the hinge accounts for the dip in helix propensity 5–7 residues after the RR-motif in Fig. 6 C. In some cases, neighboring sequences seem sufficient to override the helix destabilization propensities of certain residues (Fig. S6)—for example, the pre-SufI signal peptide has a glycine-7 residues after the RR-motif (G13), yet a helical structure is predicted to continue until G19 (Fig. 6).

A notable feature of the hairpin-hinge hypothesis is that it does not require identical hairpin structures for all Tat signal peptides. Although the TatBC binding pocket could certainly be designed to coerce all signal peptides to adopt helix-hinge-disordered structures similar to that predicted for receptor-bound pre-SufI (Fig. 6 B), the high variability of predicted signal sequence secondary structures and the lack of a strict conservation for helix destabilizing residues (Figs. S6 and S8) suggest that this is unlikely. Importantly, the length of the helix after the RR-motif, and consequently, the position of the hinge, does not have to be the same for all signal peptides. Translocation using a hairpin-hinge mechanism can occur for either shallower or deeper membrane penetration depths of the signal peptide in the initial receptor-substrate complex. Note that the attachment of a BODIPY dye to the G19 hinge of pre-SufI (or the neighboring A18 or A20 residues) could certainly hinder the normal postulated hinging function of this residue, but because the signal peptide residues after this position are predicted to be disordered (Fig. 6 A), other residues can provide the necessary flexibility for unhinging of the hairpin.

The hairpin-hinge hypothesis provides a simple, yet elegant, solution for how the signal peptide can remain bound to the receptor complex for the duration of the transport cycle while simultaneously allowing mature domain movement across the membrane. We now speculate on the nature of the translocation passageway. Due to the short linker between the signal peptide hairpin and the mature domain, it is structurally impossible for translocation to occur through a preformed or independently assembled distinct channel (69, 75, 76) while retaining significant signal peptide binding interactions (unless the signal peptide penetrates through the walls of this channel). Instead, we propose that a translocation conduit is created in the vicinity of the signal peptide binding site by recruitment of TatA. In the case of a proteinaceous pore, the signal peptide binding site would line the inside of the translocation channel, and translocation could readily occur by Brownian motion due to the hinge in the signal peptide. Disassembly of the translocation pore could reset the system for another round of transport. These concepts are schematically illustrated in Fig. 9. Note that recruitment of enough TatA to sufficiently weaken the membrane seal, but insufficient to form a complete proteinaceous pore, is also possible (77, 78). This is consistent with the hypothesis that TatA functions similarly to antimicrobial peptides (79, 80).

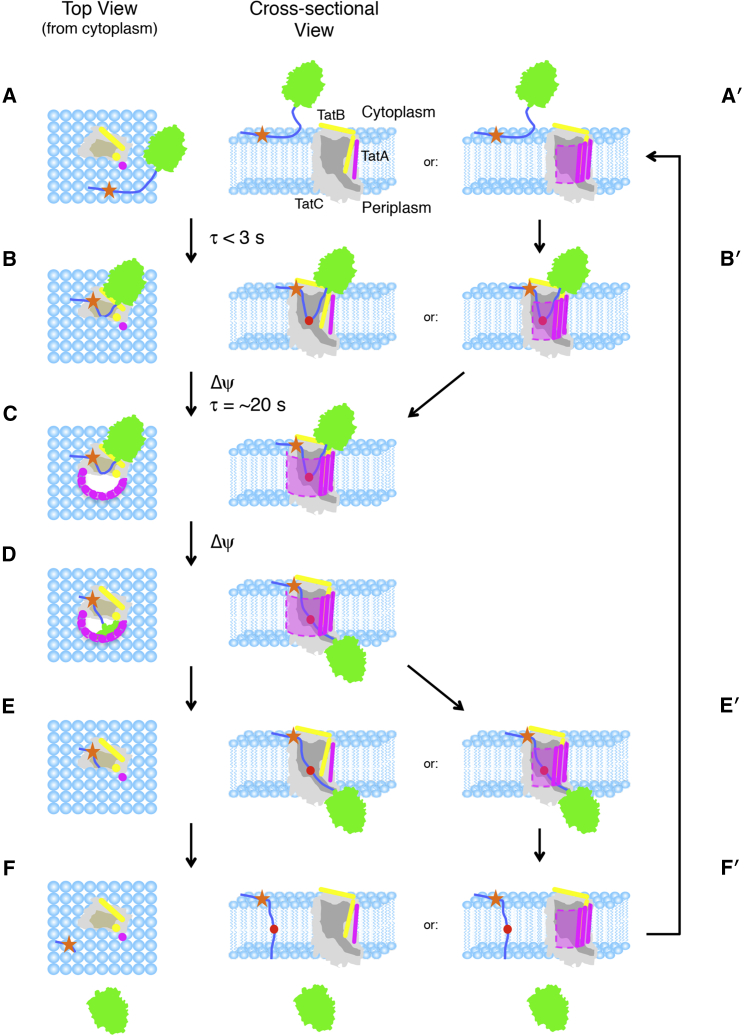

Figure 9.

Hairpin-hinge model of Tat translocation. (A) The precursor protein (green) binds to the membrane lipids via its signal peptide (dark blue) (34, 36). (B) Binding to the membrane surface, diffusion to the receptor complex, and membrane insertion of the signal peptide hairpin occurs rapidly (<3 s) and is pmf-independent (29). The RR-motif (orange star) interacts with E15 and E103 of TatC (gray) (12) and the C-terminal end of the signal peptide after the hinge (red) interacts with TatB (yellow). The amphipathic helix of TatB likely contacts the mature domain (19). (C) In the presence of a transmembrane electric field gradient (Δψ), TatA (purple) is recruited to the precursor/receptor complex, resulting in formation of a translocation conduit (pink and dashed outline) with a time constant of ∼20 s (15, 29). (D) Unhinging of the signal peptide hairpin allows the mature domain to translocate across the membrane. (E) The translocation conduit disintegrates after transport. When the pmf is collapsed, TatA dissociates with a time constant of ∼10 s (15). (F) The signal peptide is cleaved from the mature domain by signal peptidase and diffuses into the membrane bilayer, where it is subsequently degraded (81). (E′) In a variation of this model, TatA does not completely dissociate from the receptor complex after mature domain translocation. In this scenario, the translocation conduit can be gated (sealed closed) by movement of lipids into the translocation passageway (not shown). (F′) The signal peptide is released through the lateral lipid-filled gate into the membrane. (A′ and B′) In the presence of high precursor concentrations, recruitment of a new cargo molecule occurs before complete pore disassembly. For clarity, the cytoplasmic domains of TatA and TatB are not shown. These domains may play a role in gating the translocation channel and/or the formation of the pore itself.

The translocation mechanism proposed in Fig. 9 allows for an interesting solution to the problem of gating, which we define as the opening and closing of a translocation conduit. Recruitment of TatA to the precursor-receptor complex resulting in a pore-shaped structure does not automatically produce a hole through the membrane because the lipids surrounding the original independent entities are expected to occlude any potential pore. The lipids remaining within such a pore could simply diffuse away from the membrane, or, more likely, escape laterally into the membrane bilayer as the pore nears completion. A lateral escape route for the lipids blocking the translocation channel implies that pore gating could be accomplished by controlling the escape and reentry of the lipids. Thus, the translocation channel could close without complete disassembly of the translocation complex after each substrate is transported (see variation to the model in Fig. 9). In this way, multiple translocation events could occur per assembly cycle, with the signal peptide leaving through the same gate used by the lipids after each cycle. This mechanism is consistent with recent in vivo observations in which translocation complexes remained intact as long as precursor and pmf were present (15). This lipid-gating concept is conceptually similar to the membrane-weakening hypothesis (77, 78). These intact translocation complexes would therefore be “active” translocons, in contrast with the TatBC oligomers observed in the absence of a pmf, which may be more appropriately termed “resting” configurations. Although these concepts require further testing, the hairpin-hinge hypothesis provides a framework to build on to test these ideas.

Author Contributions

S.H. and S.M.M. designed research. S.H., U.K.B., and S.M.M. developed methods. S.H. and T.S.A. performed research. S.H., T.S.A., and S.M.M. analyzed data, and S.H., T.S.A., and S.M.M. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. L. Yahr for pET-SufI, pTatABC and antibodies to TatA, TatB, and TatC; M. Mueller for antibodies to TatC; T. Palmer for MC4100(DE3) and MC4100ΔTatABCDE; and J. Wiktorowicz, X. Luo, and the Mass Spectrometry Core in the University of Texas Medical Branch Biomolecular Resource Facility for mass spectrometry.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (under GM065534 and GM116995 to S.M.M.) and the Welch Foundation (under BE-1541 to S.M.M.).

Editor: Joseph Falke.

Footnotes

Eleven figures and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)31091-3.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Santini C.L., Ize B., Wu L.F. A novel Sec-independent periplasmic protein translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1998;17:101–112. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cline K., Ettinger W.F., Theg S.M. Protein-specific energy requirements for protein transport across or into thylakoid membranes. Two lumenal proteins are transported in the absence of ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:2688–2696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer T., Berks B.C. The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:483–496. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berks B.C. The twin-arginine protein translocation pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:843–864. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bageshwar U.K., Musser S.M. Two electrical potential-dependent steps are required for transport by the Escherichia coli Tat machinery. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:87–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun N.A., Davis A.W., Theg S.M. The chloroplast Tat pathway utilizes the transmembrane electric potential as an energy source. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1993–1998. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.098731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berks B.C. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol. Microbiol. 1996;22:393–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargent F., Bogsch E.G., Palmer T. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:3640–3650. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mould R.M., Robinson C. A proton gradient is required for the transport of two lumenal oxygen-evolving proteins across the thylakoid membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:12189–12193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berks B.C., Palmer T., Sargent F. The Tat protein translocation pathway and its role in microbial physiology. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2003;47:187–254. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(03)47004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramasamy S., Abrol R., Clemons W.M.J., Jr. The glove-like structure of the conserved membrane protein TatC provides insight into signal sequence recognition in twin-arginine translocation. Structure. 2013;21:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]