Abstract

The crosstalk of multiple cellular signaling pathways is crucial in animal development and tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation may result in tumor formation and metastasis. The Hedgehog (Hh) and Wnt signaling pathways are both considered to be essential regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation and oncogenesis. Recent studies have indicated that the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways are closely associated and involved in regulating embryogenesis and cellular differentiation. Hh signaling acts upstream of the Wnt signaling pathway, and negative regulates Wnt activity via secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1), and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway downregulates Hh activity through glioma-associated oncogene homolog 3 transcriptional regulation. This evidence suggests that the imbalance of Hh and Wnt regulation serves a crucial role in cancer-associated processes. The activation of SFRP1, which inhibits Wnt, has been demonstrated to be an important cross-point between the two signaling pathways. The present study reviews the complex interaction between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways in embryogenesis and tumorigenicity, and the role of SFRP1 as an important mediator associated with the dysregulation of the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways.

Keywords: Hedgehog signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, interaction, secreted frizzled-related protein 1

1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the predominant causes of human mortality worldwide. Despite several decades of unremitting efforts towards preventing and curing cancer, the translation of detailed molecular knowledge into more efficient cancer therapies remains a significant medical challenge. Cancer cells harbor a considerable number of genetic and epigenetic alterations; however, only a limited number of these alterations drive cancer progression. Tumor formation and metastasis is dependent on intracellular and intercellular signal transduction (1–5). Emerging data indicate that the crosstalk of multiple signaling pathways may account for malignant proliferation and metastasis (6–9). However, recent research has mainly focused on single pathways, ignoring the complexity of signaling networks. Exploration of the cross-regulation of signaling pathways may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dissemination of information in such networks.

The most active field of research is that of the Hedgehog (Hh) and Wnt signaling pathways, which represent essential regulators of cell proliferation and differentiation during embryogenesis and tumorigenicity (10,11). Convergence of the two pathways involving secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1) has been demonstrated (12,13). Nevertheless, studies regarding the interactions among signaling pathways are rare. The current review summarizes the most relevant literature regarding the cooperative interaction between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways, and the role of SFRP1 as an important mediator of certain oncogenic and pro-metastatic activities that are associated with the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways. The targeted inhibition of this key point in the pathways has potential with regard to the development of therapies for cancer.

2. The Hh signaling pathway

The Hh signaling pathway is an important cascade for cellular growth and differentiation during the embryonic development. The pathway was first identified in Drosophila fruit flies, and has been shown to be highly conserved in vertebrates and invertebrates (14–16). The Hh signaling pathway is complex and involves numerous regulatory proteins. In vertebrates, three Hh homologs have been identified: Sonic Hh (Shh), Indian Hh (Ihh), and desert Hh (Dhh) (17–19). Notably, the three Hh ligands activate the same signal transduction pathway, but regulate different organ systems: Shh is most widely expressed in the central nervous system, lungs, teeth, gut and hair follicles (20–24), while Ihh is involved in endochondral bone formation (25), and Dhh is expressed mostly in the gonads (26).

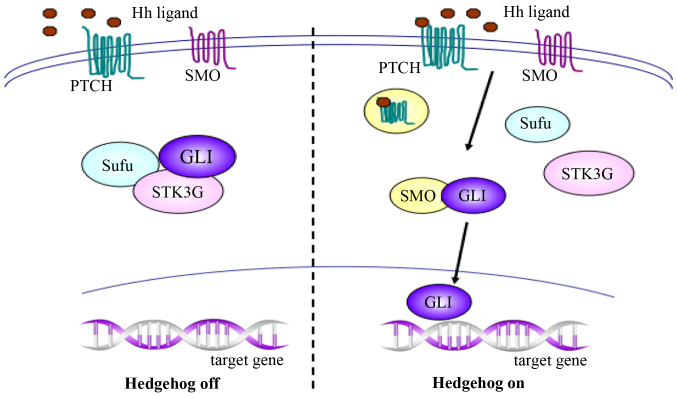

To initiate the signaling pathway, the Hh ligand binds to its receptor, a 12-transmembrane Patched (PTCH) protein, which also has two known human homologs, PTCH1 and PTCH2. In the absence of Hh, PTCH forms an inactive complex with the downstream protein Smoothened (SMO), and works as a suppressor or inhibitory protein of SMO. When Hh is activated, binding of the Hh ligand to PTCH results in endocytosis of the PTCH-ligand complex, followed by migration of activated SMO to the cytoplasm and association with glioma-associated oncogene homolog (GLI) proteins. The GLI proteins subsequently migrate into the nucleus and promote the transcription of target genes, which are responsible for cellular growth and differentiation during embryonic development, and are involved in tissue repair and cancer occurrence and development in adults (Fig. 1) (7,27).

Figure 1.

Activation of the Hh signaling pathway results in the activation of SMO and migration of GLI into nucleus. Hh, Hedgehog; SMO, Smoothened; GLI, glioma-associated oncogene homolog; PTCH, Patched; Sufu, Suppressor of fused; STK3, serine/threonine kinase 3.

Dysregulation of the Hh signaling pathway has now been implicated in various types of human malignancy, including gastrointestinal, bladder and ovarian carcinomas, lung cancer, and hematological malignancies (28–35). Aberrant activation of the Hh signaling pathway in human cancers can occur in three ways. In the first, mutated component proteins can be secreted from cells and constantly activate Hh signaling pathway. An example of this is the inactivation of PTCH or oncogenic activation of SMO, which have been demonstrated to be common features in a high proportion of tumors. To date, this mode of Hh signaling is considered the most important for tumor development (36–40). The second mode of aberrant activation is autocrine: The Hh ligand is secreted by tumor cells and also affects the tumor cells themselves (41,42). In the third mode, which is paracrine activation, tumor cells secrete Hh ligands to act on peripheral stroma cells, which activates vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor and Wnt signaling pathways to promote self-proliferation (43,44). A paracrine pattern in which stromal cells secret Hh ligands, thus contributing to the activation of Hh signaling in the tumor cells, has also been described (45).

Based on the etiological study of the Hh signaling pathway, molecular targeted therapy is considered a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer. For example, methods for increasing the inhibitory action of PTCH or suppressing the activation of SMO may be utilized the treatment of tumors with a hyper-activated Hh pathway. A number of small molecule SMO antagonists have been evaluated in clinical trials and demonstrated promising therapeutic benefits (46,47). Vismodegib, a small 2-pyridyl amide molecule, blocks Hh signaling by selectively inhibiting SMO, and thus prevents the consequent induction of target genes (48). The therapeutic success of Hh inhibitors also depends on their appropriate combination with other drugs that target cooperative signaling pathways (49–51); therefore, the points of interaction between Hh and other signaling pathways in malignancies may be potential therapeutic targets.

3. The Wnt signaling pathway

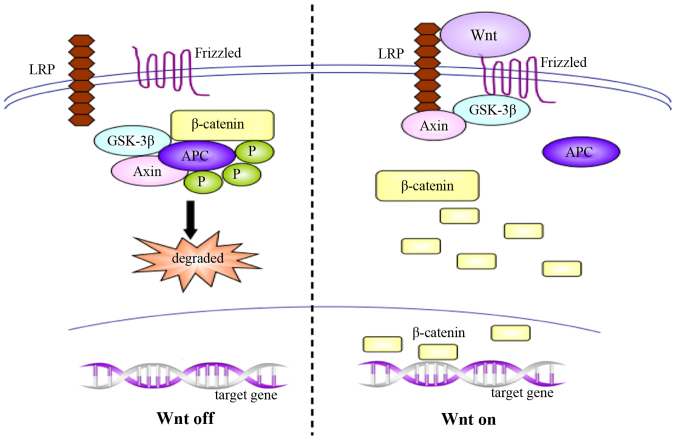

The Wnt signaling pathway participates in the physiological processes of embryonic development, cellular proliferation and differentiation, and also plays an important role in the occurrence and development of various malignancies (52–55). Wnt signaling is conducted via three pathways, as follows. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is considered the most important pathway, results in the accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus and initiates the expression of target genes. In normal organisms, Wnt pathway is inactivated, and unconjugated β-catenin is scarce; the majority of the β-catenin molecules are combined with glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and Axin, which lead to the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin via the ubiquitin pathway. Conversely, activation of the Wnt signaling pathway inhibits the GSK-3β/APC/Axin complex, inducing the abnormal accumulation and translocation to the nucleus of β-catenin, and resulting in gene transcription (Fig. 2) (56–58). In another pathway, Wnt5a and Wnt11 activate cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and protein kinase C to increase cellular Ca2+ concentration, and promote nuclear factor of activated T-cells-induced gene transcription; this pathway is designated the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway (59). The third pathway, Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling pathway mainly participates in the regulation of cytoskeletal rearrangement during embryonic development (60). The present review primarily focuses on the functional interaction between the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and the Hh signaling pathway.

Figure 2.

The Wnt signaling pathway leads to the accumulation of β-catenin in nucleus. LRP, lipoprotein receptor-related protein; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; P, phosphate.

Inappropriate activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is associated with a variety of malignant diseases, such as gallbladder, lung and breast cancers (61–63); therefore, the development of drugs targeting this pathway is an area of interest with regard to cancer therapy research. Several Wnt inhibitors have been investigated in preclinical studies; for example, Lu et al(64) demonstrated that salinomycin is a potent inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway and acts by interfering with lipoprotein-related receptor 6 phosphorylation, and an anti-Frizzled antibody is currently being tested as potential cancer therapy (65,66). Although therapies targeting the Wnt signaling pathway are attractive in theory, in practice it has been difficult to create specific therapeutic agents, as numerous components of the Wnt signaling pathways are also involved in other cellular processes. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway has been demonstrated to have crosstalk with other signaling pathways, such as the Hh, NOTCH, Hippo and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways (12,13,67–69). Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms and biological functions of these pathways may reveal potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of tumors.

4. Interaction between Hh and Wnt signaling promotes embryogenesis and cellular differentiation

The network of signaling pathways, including Hh, Wnt, signal transducer and transcription activator (STAT) and NOTCH, contributes to cellular proliferation and differentiation, and to maintaining the stability of the internal environment (14–16,52–55). In invertebrates and lower vertebrates, activation of Wnt and Hh signaling pathways is crucial in embryogenesis and cellular differentiation (70,71). Previous evidence has indicated that the expression of myogenic basic helix-loop-helix genes in embryonic somites can be induced by the Wnt and Shh signaling pathways (65). Despite complete truncation, the limbs of amphibians show remarkable regeneration through wound healing, blastema formation and tissue differentiation (72–74). Pharmacological research has revealed the integration between Hh and Wnt signaling via active and inhibitory drugs. The Hh pathway acts upstream of Wnt to inhibit the activation of Wnt signaling; however, Wnt activation may rescue the suppressive signaling of Hh in regulating amphibian limb regeneration (75). The synergetic interaction was postulated by Day et al(76), who reported that Ihh signaling is activated at an early stage of osteoblast maturation during fracture repair, and that Wnt signaling is subsequently upregulated in differentiated osteoblasts. Further research has indicated that the deletion of the motor protein kinesin family member 3A in dental mesenchyme results in the suppression of Hh and activation of Wnt, affecting incisor and molar development (77). These findings may reveal as association between the two signaling pathways at the gene level. In addition, Oberhofer et al(78) investigated Hh and Wnt signaling in the head anlagen and growth zone of early insect embryos, and indicated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling acts upstream of Hh in the growth zone, yet downstream of Hh in the head, anlagen, suggesting the different roles of Hh and Wnt in these two regions (78).

Shin et al(79) reported a proliferative response to bacterial infection and chemical injury within the bladder in a mouse model, and demonstrated that the response is regulated by signal feedback between basal cells and stromal cells. In bacterial injury, Shh expression in the basal cells is activated and induces increased Wnt protein expression in the stromal cells. The increased activity of this signal circuit may help prevent the further spread of infection, and stimulate the restoration of urothelial and stromal cells (79). These findings demonstrate an interaction between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways. Thus, there is evidence to suggest that organisms require a precise balance of these signaling pathways to control proliferation and differentiation.

5. The Hh signaling pathway attenuates Wnt activity through activated SFRP1.

Although a number of studies have demonstrated that synergy between the two pathways promotes embryogenesis and cellular differentiation, conflicting data has also been reported that the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways are functionally antagonistic in vertebrates and invertebrates (80–84). The crosstalk protein SFRP1, which acts as an antagonist of Wnt signaling, was initially identified in 1998, and has subsequently been shown to be regulated by Hh in the developing spinal cord and gastric cancer cells (12,80–82). Borday et al(83) investigated the potential cross-regulation between the Wnt and Hh signaling pathways in neural stem/progenitor cells in the ciliary marginal zones using pharmacological tools. They detected Wnt activity and subsequently Hedgehog inhibition by 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime treatment, which worked as a selective activator of the canonical Wnt pathway. By contrast, Hedgehog signaling restricts Wnt activity, using Smoothened agonist purmorphamine, which was sufficient for activation of Hedgehog signaling. Furthermore, Hh signaling pathway negatively regulates Wnt activity via transcriptional regulation of SFRP1, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway downregulates Hedgehog activity through et al transcriptional regulation. The reciprocal inhibition between Hh and Wnt signaling pathways regulates a delicate balance between proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells (83).

Although the Wnt and Hh signaling pathways participate in the physiological processes of cellular proliferation and differentiation, recent research has indicated that the two pathways also serve a crucial role in the pathological processes of various diseases, particularly malignancies. For example, enhanced Shh signaling restricts canonical Wnt signaling in the lambdoidal region by promoting the expression of genes encoding Wnt inhibitors, which is involved in the development of cleft lip (85). In addition, downregulation of Ihh expression may contribute to the activation of Wnt signaling via APC mutation, and subsequently lead to the development of colorectal tumors (86). Further studies have indicated that Wnt signaling may be a downstream pathway of Hh signaling, and that SFRP1 acts as an important cross-point to repress the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and restrict the expression of Wnt target genes. A gene chip assay of squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix revealed that the expression of Hh signaling molecules was significantly increased in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II/III and carcinoma, while SFRP1 gene expression was silent or low, which strongly suggests that the differential activation of the Wnt and Hh pathways may be involved in the development of uterine cervical carcinoma (87).

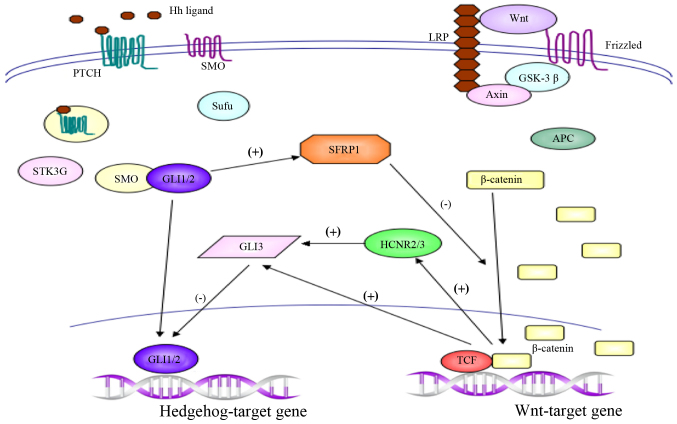

Kim et al(84) investigated differentiation-associated signal interactions between the Wnt and Hh signaling pathways in gastric cancer cells, and indicated that the expression levels of Shh signaling components were increased, whereas those of the Wnt signaling pathway were decreased. Further research indicated that ectopic expression of GLI1 increased the level of SFRP1 transcript, and that increased expression of GLI1 decreased nuclear β-catenin staining. By contrast, inhibition of GLI1 reduced SFRP1 expression. Thus, the Shh and Wnt pathways are differentially involved according to the differentiation of gastric cancer cells (84) (Fig. 3). Clinical studies have also demonstrated that the upregulation of Shh protein is associated with age, pathological status, tumor differentiation, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis of gastric cancer, and Shh protein overexpression is considered a significant independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer (88).

Figure 3.

Crosstalk between the Hh and Wnt pathways forms regulatory loops. The Hh signaling pathway negative regulates Wnt activity via SFRP1, and Wnt/β-catenin pathway feedback regulates Hh activity via GLI3 transcriptional regulation. Hh, Hedgehog; SFRP1, secreted frizzled-related protein 1; GLI, glioma-associated oncogene homolog; PTCH, Patched; SMO, Smoothened; Sufu, Suppressor of fused; STK3, serine/threonine kinase 3; LRP, lipoprotein receptor-related protein; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; HCNR2/3, highly conserved non-coding DNA region 2/3; TCF, T cell factor.

6. Wnt/β-catenin pathway feedback regulates Hh activity through transcriptional regulation of GLI3.

GLI3 is known to be a transcriptional repressor of the Hh signaling pathway in the absence of ligand stimulation (89). Alvarez-Medina et al(90) investigated dorsoventral neuron development, which is achieved by the combined activity of signaling pathways. In their study, the canonical Wnt signaling pathway was demonstrated to be important in dorsoventral patterning of the spinal cord, and this role was largely dependent on GLI activity. Furthermore, the study revealed that the expression of GLI3 within the dorsal neural tube is directly controlled by Wnt activity, as mice with mutated Wnt1 and Wnt3a exhibited diminished GLI3 expression, and gain and loss of β-catenin/T cell factor (β-catenin/Tcf) function in chick embryos also directly regulated GLI3 expression (90). Furthermore, previous studies characterized four highly conserved non-coding DNA regions (HCNRs) within the human GLI3 locus that work as potential enhancer modules; it was demonstrated that HCNR2 and HCNR3 contain sufficient information to direct the expression of GLI3 in the dorsal spinal cord, and that the activity of these two modules is dependent on β-catenin/Tcf transcriptional activity (90–92). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway downregulates GLI3 expression, indicating an indirect mechanism initiated by Wnt signaling to repress Shh activity in the dorsal neural tube (90–92).

Borday et al(83) performed a pharmacological study using 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO) to selectively inhibit GSK-3, which resulted in a significant increase in GLI3 expression. In addition, treatment with IWR-1, which prevents Axin protein degradation, led to the opposite phenotype. Furthermore, morpholino-mediated GLI3 knockdown could rescue the decreased PTCH1 expression observed in BIO-treated tadpoles (83). This evidence suggests that GLI3 represents a key downstream effector of the Wnt pathway, which may account for its negative effect on Hh activity (82,93,94). Based on the research into the etiological roles of Wnt/β-catenin inhibition of Hh signaling, the preclinical study of Shh-dependent medulloblastoma is in progress, with the aim of developing novel therapeutic strategies for patients (95).

7. Conclusion

As a whole, the network of signaling pathways, such as Hh, Wnt, STAT and NOTCH, is crucial in cellular differentiation and tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation may result in tumor occurrence and metastasis. Studies from numerous laboratories have made great efforts in exploring the complexity of the regulatory networks and the interaction between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways. Inappropriate activation of Hh and Wnt signaling has been demonstrated in certain types of cancer. However, the mechanism of interaction between the two signaling pathways remains unclear, and several key questions remain to be addressed. Firstly, research has mainly been limited to cell and animal experiments, and the findings reviewed in the present study must be demonstrated in appropriate preclinical investigations. Secondly, some of the apparently conflicting reports regarding the interactions between the different signaling pathways must be studied and discussed in greater depth.

More than 20 years after the discovery of the Hh and Wnt pathways, we have entered an exciting era of research into these signaling pathways. A single pathway is susceptible to be affected by other pathways, and does not fully represent the entire signaling network. Therefore, further investigation of the crosstalk between different transcriptional signals could overcome this limitation of single pathways, and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the importance of these signaling pathways in the development of cancer. The therapeutic benefits of pathway antagonists are gradually being revealed in clinical studies, and the outcomes may have a far-reaching impact on the design of novel cancer therapies. In summary, the interactions between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways in malignancies may provide a theoretical basis for potential cancer therapies.

Acknowledgements

This review article was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81270598 and 81473486), the National Public Health Grand Research Foundation (grant no. 201202017), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant nos. 2009ZRB14176 and ZR2012HZ003), the Technology Development Projects of Shandong Province (grant nos. 2010GSF10250 and 2014GSF118021), the Program of Shandong Medical Leading Talent, and the Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province.

References

- 1.Parmigiani G, Boca S, Lin J, Kinzler KW, Velculescu V, Vogelstein B. Design and analysis issues in genome-wide somatic mutation studies of cancer. Genomics. 2009;93:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenman CP, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, Winckler W, Laframboise T, Lin WM, Wang M, Feng W, Zander T, MacConaill L, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng0407-567a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangelberger D, Kern D, Loipetzberger A, Eberl M, Aberger F. Cooperative Hedgehog-EGFR signaling. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:90–99. doi: 10.2741/3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushita S, Onishi H, Nakano K, Nagamatsu I, Imaizumi A, Hattori M, Oda Y, Tanaka M, Katano M. Hedgehog signaling pathway is a potential therapeutic target for gallbladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:272–280. doi: 10.1111/cas.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/nrd2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:1–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karamboulas C, Ailles L. Developmental signaling pathways in cancer stem cells of sol-id tumors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:2481–2495. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodge ME, Lum L. Drugging the cancer stem cell compartment: Lessons learned from the hedgehog and Wnt signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:289–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.JP IV Morris, Wang SC, Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:683–695. doi: 10.1038/nrc2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoh Y, Katoh M. WNT antagonist, SFRP1, is Hedgehog signaling target. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bovolenta P, Esteve P, Ruiz JM, Cisneros E, Lopez-Rios J. Beyond Wnt inhibition: New functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:737–746. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nüsslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varjosalo M, Taipale J. Hedgehog signaling. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson CW, Chuang PT. Mechanism and evolution of cytosolic Hedgehog signal transduction. Development. 2010;137:2079–2094. doi: 10.1242/dev.045021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Corcoran RB, Scott MP. Hedgehog signal transduction by Smoothened: Pharmacologic evidence for a 2-step activation process; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2009; pp. 3196–3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varjosalo M, Taipale J. Hedgehog: Functions and mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2454–2472. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulate hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marigo V, Tabin CJ. Regulation of patched by sonic hedgehog in the developing neural tube; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 1996; pp. 9346–9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellusci S, Furuta Y, Rush MG, Henderson R, Winnier G, Hogan BL. Involvement of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) in mouse embryonic lung growth and morphogenesis. Development. 1997;124:53–63. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardcastle Z, Mo R, Hui CC, Sharpe PT. The Shh signalling pathway in tooth development: Defects in Gli2 and Gli3 mutants. Development. 1998;125:2803–2811. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Litingtung Y, Lei L, Westphal H, Chiang C. Sonic hedgehog is essential to foregut development. Nat Genet. 1998;20:58–61. doi: 10.1038/1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, Botchkarev VA, Li J, Danielian PS, McMahon JA, Lewis PM, Paus R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vortkamp A, Lee K, Lanske B, Segre GV, Kronenberg HM, Tabin CJ. Regulation of rate of cartilage differentiation by Indian hedgehog and PTH-related protein. Science. 1996;273:613–622. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bitgood MJ, Shen L, McMahon AP. Sertoli cell signaling by Desert hedgehog regulates the male germline. Curr Biol. 1996;6:298–304. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Jiang J. Decoding the phosphorylation code in Hedgehog signal transduction. Cell Res. 2013;23:186–200. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merchant JL. Hedgehog signaling in gut development, physiology and cancer. J Physiol. 2012;590:421–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertrand FE, Angus CW, Partis WJ, Sigounas G. Developmental pathways in colon cancer: Crosstalk between WNT, BMP, Hedgehog and Notch. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:4344–4351. doi: 10.4161/cc.22134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu Y, Li F, Tang B, Shi Y, Hao Y, Yu P. Clinicopathological correlation and prognostic significance of sonic hedgehog protein overexpression in human gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5144–5153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kai K, Aishima S, Miyazaki K. Gallbladder cancer: Clinical and pathological approach. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:515–521. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i10.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nigam A. Breast cancer stem cells, pathways and therapeutic perspectives 2011. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:170–180. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0616-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang J, Kang MH, Yoo YA, Quan YH, Kim HK, Oh SC, Choi YH. The effects of sonic hedgehog signaling pathway components on non-small-cell lung cancer progression and clinical outcome. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:268. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ok CY, Singh RR, Vega F. Aberrant activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway in malignant hematological neoplasms. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irvine DA, Copland M. Targeting hedgehog in hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2012;119:2196–2204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harwood CA, Attard NR, O'Donovan P, Chambers P, Perrett CM, Proby CM, McGregor JM, Karran P. PTCH mutations in basal cell carcinomas from azathioprine-treated organ transplant recipients. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soufir N, Gerard B, Portela M, Brice A, Liboutet M, Saiag P, Descamps V, Kerob D, Wolkenstein P, Gorin I, et al. PTCH mutations and deletions in patients with typical nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and in patients with a suspected genetic predisposition to basal cell carcinoma: A French study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:548–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nitzki F, Tolosa EJ, Cuvelier N, Frommhold A, Salinas-Riester G, Johnsen SA, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Hahn H. Overexpression of mutant Ptch in rhabdomyosarcomas is associated with promoter hypomethylation and increased Gli1 and H3K4me3 occupancy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9113–9124. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim CB, Prêle CM, Cheah HM, Cheng YY, Klebe S, Reid G, Watkins DN, Baltic S, Thompson PJ, Mutsaers SE. Mutational analysis of hedgehog signaling pathway genes in human malignant mesothelioma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Li S, Tong C, Zhao Y, Wang B, Liu Y, Jia J, Jiang J. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 promotes high-level Hedgehog signaling by regulating the active state of Smo through kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2054–2067. doi: 10.1101/gad.1948710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Liu Z, Jang F, Xiang C, Li Y, He Y. Autocrine Sonic hedgehog attenuates inflammation in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice via upregulation of IL-10. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ertao Z, Jianhui C, Chuangqi C, Changjiang Q, Sile C, Yulong H, Hui W, Shirong C. Autocrine Sonic hedgehog signaling promotes gastric cancer proliferation through induction of phospholipase Cy1 and the ERK1/2 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:63. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0336-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levi B, James AW, Nelson ER, Li S, Peng M, Commons GW, Lee M, Wu B, Longaker MT. Human adipose-derived stromal cells stimulate autogenous skeletal repair via paracrine Hedgehog signaling with calvarial osteoblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:243–257. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan IS, Guy CD, Chen Y, Lu J, Swiderska-Syn M, Michelotti GA, Karaca G, Xie G, Krüger L, Syn WK, et al. Paracrine Hedgehog signaling drives metabolic changes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6344–6350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scales SJ, de Sauvage FJ. Mechanisms of Hedgehog pathway activation in cancer and implications for therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, Yauch RL, Callahan CA, Fu L, Holcomb T, Stinson J, Gould SE, Coleman B, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1173–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Von Hoff DD, LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Yauch RL, Tibes R, Weiss GJ, Borad MJ, Hann CL, Brahmer JR, et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1164–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubey AK, Dubey S, Handu SS, Qazi MA. Vismodegib: The first drug approved for advanced and metastatic basal cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2013;59:48–50. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.109494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stecca B, Ruiz I, Altaba A. Context-dependent regulation of the GLI code in cancer by HEDGEHOG and non-HEDGEHOG signals. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:84–95. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lauth M, Toftgård R. Non-canonical activation of GLI transcription factors: Implications for targeted anti-cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2458–2463. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riobo NA, Lu K, Emerson CP., Jr Hedgehog signal transduction: Signal integration and cross talk in development and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1612–1615. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muñoz-Descalzo S, Hadjantonakis AK, Arias AM. Wnt/ß-catenin signalling and the dynamics of fate decisions in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem (ES) cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;47-48:1–109. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sokol SY. Maintaining embryonic stem cell pluripotency with Wnt signaling. Development. 2011;138:4341–4350. doi: 10.1242/dev.066209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang K, Wang X, Zhang H, Wang Z, Nan G, Li Y, Zhang F, Mohammed MK, Haydon RC, Luu HH, et al. The evolving roles of canonical WNT signaling in stem cells and tumorigenesis: Implications in targeted cancer therapies. Lab Invest. 2016;96:116–136. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohammed MK, Shao C, Wang J, Wei Q, Wang X, Collier Z, Tang S, Liu H, Zhang F, Huang J, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an ever-expanding role in stem cell self-renewal, tumorigenesis and cancer chemoresistance. Genes Dis. 2016;3:11–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalderon D. Similarities between the Hedgehog and Wnt signaling pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:523–531. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He X, Semenov M, Tamai K, Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: Arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peifer M, McEwen DG. The ballet of morphogenesis: Unveiling the hidden choreographers. Cell. 2002;109:271–274. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shigemitsu K, Sekido Y, Usami N, Mori S, Sato M, Horio Y, Hasegawa Y, Bader SA, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, et al. Genetic alteration of the beta-catenin gene (CTNNBI) in human lung cancer and malignant mesothelioma and identification of a new 3p21.3 homozygous deletion. Oncogene. 2001;20:4249–4257. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kimura Y, Furuhata T, Mukaiya M, Kihara C, Kawakami M, Okita K, Yanai Y, Zenbutsu H, Satoh M, Ichimiya S, Hirata K. Frequent beta-catenin alteration in gallbladder carcinomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coscio A, Chang DW, Roth JA, Ye Y, Gu J, Yang P, Wu X. Genetic variants of the Wnt signaling pathway as predictors of recurrence and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer patients. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1284–1291. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li S, Li S, Sun Y, Li L. The expression of β-catenin in different subtypes of breast cancer and its clinical significance. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:7693–7698. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1975-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu D, Choi MY, Yu J, Castro JE, Kipps TJ, Carson DA. Salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells; Proc Matl Acad Sci USA; 2011; pp. 13253–13257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Price MA. CKI, there's more than one: casein kinase I family members in Wnt and Hedgehog signaling. Genes Dev. 2006;20:399–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.1394306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhee CS, Sen M, Lu D, Wu C, Leoni L, Rubin J, Corr M, Carson DA. Wnt and frizzled receptors as potential targets for immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:6598–6605. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collu GM, Hidalgo-Sastre A, Brennan K. Wnt-Notch signaling crosstalk in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3553–3567. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1644-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu F, Zhang J, Ma D. Crosstalk of Hippo/YAP and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Yi Chuan. 2014;36:95–102. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1005.2014.00095. (In Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimobayashi M, Hall MN. Making new contacts: The mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:155–162. doi: 10.1038/nrm3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moussaif M, Sze JY. Intraflagellar transport/Hedgehog-related signaling components couple sensory cilium morphology and serotonin biosynthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4065–4075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0044-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brás-Pereira C, Potier D, Jacobs J, Aerts S, Casares F, Janody F. dachshund Potentiates Hedgehog Signaling during Drosophila Retinogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poss KD, Keating MT, Nechiporuk A. Tales of regeneration in zebrafish. Dev Dyn: 2003;226:202–210. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Akimenko MA, Mari-Beffa M, Becerra J, Géraudie J. Old questions, new tools, and some answers to the mystery of fin regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:190–201. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Riehle KJ, Hubbert C, Major MB, Fausto N, Moon RT. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh BN, Doyle MJ, Weaver CV, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry DJ. Hedgehog and Wnt coordinate signaling in myogenic progenitors and regulate limb regeneration. Dev Biol. 2012;371:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Day TF, Yang Y. Wnt and hedgehog signaling pathways in bone development. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 1):S19–S24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu B, Chen S, Cheng D, Jing W, Helms JA. Primary cilia integrate hedgehog and Wnt signaling during tooth development. J Dent Res. 2014;93:475–482. doi: 10.1177/0022034514528211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oberhofer G, Grossmann D, Siemanowski JL, Beissbarth T, Bucher G. Wnt/β-catenin signaling integrates patterning and metabolism of the insect growth zone. Development. 2014;141:4740–4750. doi: 10.1242/dev.112797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin K, Lee J, Guo N, Kim J, Lim A, Qu L, Mysorekar IU, Beachy PA. Hedgehog/Wnt feedback supports regenerative proliferation of epithelial stem cells in bladder. Nature. 2011;472:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu Q, D'Amore PA, Sokol SY. Functional and biochemical interactions of Wnts with FrzA, a secreted Wnt antagonist. Development. 1998;125:4767–4776. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.He J, Sheng T, Stelter AA, Li C, Zhang X, Sinha M, Luxon BA, Xie J. Suppressing Wnt signalling by the hedgehog pathway through sFRP-1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35598–35602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alvarez-Medina R, Le Dreau G, Ros M, Marti E. Hedgehog activation is required upstream of Wnt signalling to control neural progenitor proliferation. Development. 2009;136:3301–3309. doi: 10.1242/dev.041772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borday C, Cabochette P, Parain K, Mazurier N, Janssens S, Tran HT, Sekkali B, Bronchain O, Vleminckx K, Locker M, Perron M. Antagonistic cross-regulation between Wnt and Hedgehog signalling pathways controls post-embryonic retinal proliferation. Development. 2012;139:3499–3509. doi: 10.1242/dev.079582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim JH, Shin HS, Lee SH, Lee I, Lee YS, Park JC, Kim YJ, Chung JB, Lee YC. Contrasting activity of Hedgehog and Wnt pathways according to gastric cancer cell differentiation: Relevance of crosstalk mechanisms. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kurosaka H, Lulianella A, Williams T, Trainor PA. Disrupting hedgehog and WNT signaling interactions promotes cleft lip pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1660–1671. doi: 10.1172/JCI72688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fu X, Shi L, Zhang W, Zhang X, Peng Y, Chen X, Tang C, Li X, Zhou X. Expression of Indian hedgehog is negatively correlated with APC gene mutation in colorectal tumors. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2150–2155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xuan YH, Jung HS, Choi YL, Shin YK, Kim HJ, Kim KH, Kim WJ, Lee YJ, Kim SH. Enhanced expression of hedgehog signaling molecules in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and its precursor lesions. Mod Patho. 2006;19:1139–1147. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yanai K, Nakamura M, Akiyoshi T, Nagai S, Wada J, Koga K, Noshiro H, Nagai E, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M, Katano M. Crosstalk of hedgehog and Wnt pathways in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;263:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jacob J, Briscoe J. Gli proteins and the control of spinal-cord patterning. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:761–765. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alvarez-Medina R, Cayuso J, Okubo T, Takada S, Marti E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135:237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muroyama Y, Fujihara M, Ikeya M, Kondoh H, Takada S. Wnt signalling plays an essential role in neuronal specification of the dorsal spinal cord. Genes Dev. 2002;16:548–553. doi: 10.1101/gad.937102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abbasi AA, Paparidis Z, Malik S, Goode DK, Callaway H, Elgar G, Grzeschick KH. Human GLI3 intragenic conserved non-coding sequences are tissue-specific enhancers. PLoS One. 2007;2:e366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meijer L, Skaltsounis AL, Magiatis P, Polychronopoulos P, Knockaert M, Leost M, Ryan XP, Vonica CA, Brivanlou A, Dajani R, et al. GSK-3-selective inhibitors derived from Tyrian purple indirubins. Chem Biol. 2003;10:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signalling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pöschl J, Bartels M, Ohli J, Bianchi E, Kuteykin-Teplyakov K, Grammel D, Ahlfeld J, Schüller U. Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibits the Shh pathway and impairs tumor growth in Shh-dependent medulloblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:605–607. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]