Abstract

Introduction

Depression often co-occurs with chronic back pain (CBP). Internet and mobile-based interventions (IMIs) might be a promising approach for effectively treating depression in this patient group. In the present study, we will evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a guided depression IMI for individuals with CBP (eSano BackCare-D) integrated into orthopaedic healthcare.

Methods and analysis

In this multicentre randomised controlled trial of parallel design, the groups eSano BackCare-D versus treatment as usual will be compared. 210 participants with CBP and diagnosed depression will be recruited subsequent to orthopaedic rehabilitation care. Assessments will be conducted prior to randomisation and 9 weeks (post-treatment) and 6 months after randomisation. The primary outcome is depression severity (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-17). Secondary outcomes are depression remission and response, health-related quality of life, pain intensity, pain-related disability, self-efficacy and work capacity. Demographic and medical variables as well as internet affinity, intervention adherence, intervention satisfaction and negative effects will also be assessed. Data will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis with additional per-protocol analyses. Moreover, a cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis will be conducted from a societal perspective after 6 months.

Ethics and dissemination

All procedures are approved by the ethics committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-University of Freiburg and the data security committee of the German Pension Insurance (Deutsche Rentenversicherung). The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented on international conferences.

Trial registration number

DRKS00009272; Pre-results.

Keywords: depression, chronic back pain, e-mental-health, health care services research, randomized controlled trial, study protocol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a protocol for the first large-scale, multicentre randomised controlled trial examining the effectiveness of a depression internet and mobile-based intervention (IMI) for individuals with chronic back pain (CBP) and depression.

This is the first trial examining the cost-effectiveness of a depression IMI for individuals with CBP and depression.

The IMI will be implemented as integrated part of routine orthopaedic healthcare, thus overcoming the self-referral bias of most prior IMI trials, examining the possibility to improve patients' medical sector transitions by means of an e-mental-health offer.

We use standardised interviews for the diagnosis and clinical rating scales for the assessment of the severity level of depression (Structured Clinical Interview and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression/Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology).

Findings will be limited to patients with back pain and depression receiving a depression IMI as aftercare intervention of a biopsychosocial focused orthopaedic inpatient treatment, which might limit the (incremental) effectiveness of the intervention.

Introduction

The two widespread conditions chronic back pain (CBP) and depression belong to the top 10 causes of years lived with disability worldwide.1 The global 1-month adult prevalence for low back pain is estimated to be 23.2% and a substantial increase during the next decades can be expected.2 Depression has been shown to be the leading cause of burden of diseases in middle-income to high-income countries with a lifetime prevalence of about 14.6% in high-income countries.3 A strong association between depression and CBP has been frequently reported with prevalence rates for depression ranging from 21% to 50% in back pain and chronic low back pain individuals.4 Several systematic reviews highlight a significant prognostic association between comorbid depression and increased morbidity of different somatic conditions and healthcare costs as well as diminished quality of life.5–7 Moreover, depression is one of the core predictors of persistent pain symptoms, increased pain-related disability and poor treatment outcomes in pain patients.4 8 9

There is evidence for the efficacy of psychological interventions for chronic pain10 and also for chronic low back pain in specific 11 aiming at pain intensity or disability/interference as primary outcomes. To the best of our knowledge however, there is no study that has examined the effects of psychological depression interventions in the population of CBP focussing on depression as the primary outcome.12 Indeed, the evidence on depression treatments for patients with chronic pain and clinical depression is very limited, mostly relying on a few collaborative/stepped care trials conducted in the last two decades.13–15

In order to improve healthcare for CBP individuals, internet and mobile-based interventions (IMIs) are considered to be a promising approach.16 17 Among numerous meta-analyses highlighting the efficacy of IMIs with regard to the reduction of depressive symptoms,18–21 one meta-analysis quantified the superiority of online depression interventions over waiting-list and treatment as usual (TAU) with standardised mean differences of d=−0.68 (95% CI −0.85 to −0.52; n=8) and d=−0.39 (95% CI −0.66 to −0.12; n=8),20 although effect moderating factors of IMIs remain unclear.22 As most trials used highly selective recruitment strategies, the evidence for the effectiveness of IMIs for depression (ie, performance of an intervention when implemented within typical clinical practice, investigated by means of pragmatic trials) is far less conclusive23 and many health systems have not included IMIs as an integrated treatment component. As an implemented part of a comprehensive care system, IMIs could reduce the deficiencies of most current healthcare systems in coordinating transitions of care, such as the transition from the inpatient to outpatient setting, where recommendations are regularly lost in transition.24–26

The present WARD-BP study (web-based aftercare depression intervention following rehabilitation for individuals with depression and chronic back pain) aims to investigate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the depression IMI ‘eSano BackCare-D’ in a study population of CBP with diagnosed depression in the aftermath of orthopaedic rehabilitation care. The primary research question is:

Is eSano BackCare-D effective in reducing depression in individuals with CBP and diagnosed depression compared to TAU?

Secondary research questions are:

Is eSano BackCare-D effective with regard to depression remission and response, health-related quality of life, pain intensity, pain-related disability, self-efficacy and work capacity in individuals with CBP and diagnosed depression compared to TAU?

Is eSano BackCare-D cost-effective in individuals with CBP and diagnosed depression compared to TAU from a societal perspective?

Which factors moderate and mediate the effects of eSano BackCare-D?

Methods and analysis

Study design

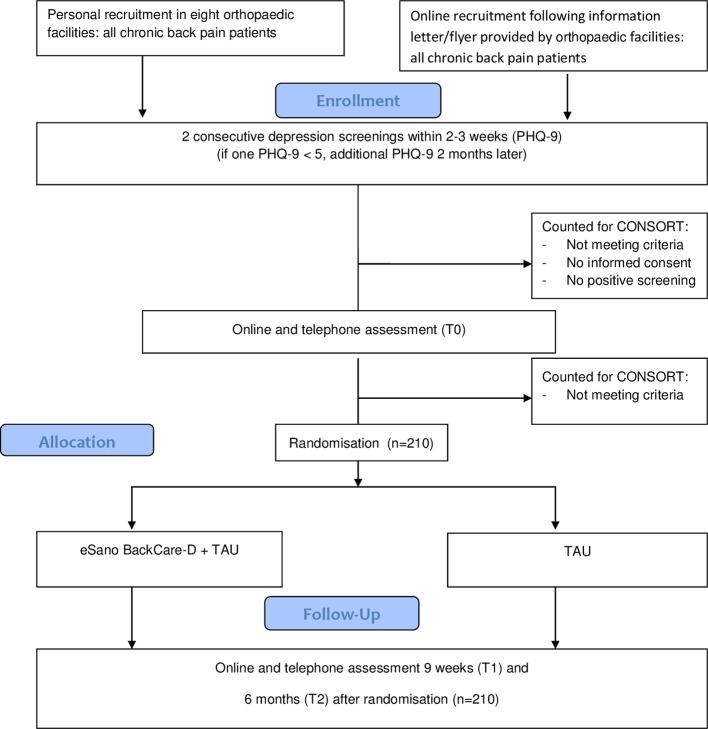

WARD-BP is a multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial (RCT) of parallel design. All participants receive TAU. We conduct assessments in both groups before randomisation (T0), 9 weeks (T1=post-treatment in case of regular IMI use) and 6 months (T2) after randomisation. Trial participants receive €15 per completed post-telephone and follow-up telephone assessment, see figure 1 for study flow.

Figure 1.

CONSORT103 Flow chart. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; TAU, treatment as usual.

Randomisation

Randomisation and allocation of participants to the two groups (intervention or TAU) was prepared in advance by an independent researcher (SaS) by means of a web-based programme (https://www.sealedenvelope.com/) using permuted block randomisation with variable block sizes of 4, 6, 8 (randomly arranged), ratio of 1:1. Participants are stratified by centre. Centres are all eight orthopaedic clinics where recruitment is conducted personally and a ninth (meta-)clinic, which includes all participants recruited by letter (see recruitment). The independent researcher (SaS) is responsible for the allocation of participants to trial arms as well as the administration of the trial and is blinded to the treatment process and assessment of the participants.

Recruitment

Recruitment has started in October 2015 and is planned to end in July 2017. While this study protocol has been submitted for publication after start of recruitment (due to usual writing-up, commenting and approving procedures by all coauthors), clinical trial registry took place prior to recruitment start.

Using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-927), we conduct two consecutive depression screenings within 2–3 weeks. In case of only one positive screening (PHQ ≥5), a third PHQ will be administered 2 months later via telephone interview. We recruit potential participants in orthopaedic rehabilitation units in Germany with two different recruitment strategies.

In the first recruitment setting (personal recruitment), patients with two positive screenings receive information on the intervention by clinic staff during their orthopaedic care. Patients providing their informed consent to the clinical trial study team (exemplary informed consent form, see online supplementary material) are contacted by the study team in order to clarify further eligibility criteria by means of an online and telephone assessment including a telephone administered clinical interview. The participating clinics are compensated for their recruitment efforts (ie, selection of back pain patients, screening procedure, informed consent, documentation according to CONSORT28–30, providing access to medical records) with €320 per randomised participant. The second recruitment strategy (recruitment by letter) involves a letter with information flyers and description of study process for back pain patients after discharge from orthopaedic rehabilitation units across Germany with a link to fill out an online PHQ-screening. Individuals screened positive and providing informed consent are contacted for the second PHQ-screening and a clinical interview via telephone equivalent to the first recruitment strategy.

bmjopen-2016-015226supp001.pdf (233KB, pdf)

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We include patients if they fulfil the following inclusion criteria:

aged 18 years or older;

CBP for at least 6 months assessed by physician;

mild-to-moderate depression or dysthymia according to the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID 31 32) during telephone interview;

sufficient knowledge of German language;

internet and PC access.

Patients are excluded in case of:

receiving ongoing psychotherapy or beginning psychotherapy within the next 3 months,

being currently suicidal or reporting suicidal attempts in the past 5 years assessed during telephone interview;

a current diagnosis of severe depression (10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) F32.2/F32.3/F33.2/F33.3 diagnosis) assessed during telephone interview, see table 1.

Table 1.

Key variables and measurements

| Variables | Measurement | Depression screenings (PHQ-9) | T0 | T1 | T2 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | |||||||

| Chronic back pain | MR+TI | x | x | ||||

| Mild-to-moderate depression or dysthymia | PHQ-9/HAM-D/QIDS/SCID | x | x | x | |||

| Severe depression (ICD-10 F32.2/F32.3/F33.2/F33.3 diagnosis) | SCID | x | x | x | |||

| Suicidality | HAM-D/QIDS/SCID | x | x | x | |||

| PHQ-9 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Further inclusion and exclusion criteria 1, 4, 5 and 6 | SRQ+TI | x | x | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| Depression severity | HAM-D | x | x | x | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Depression remission and response | HAM-D/SCID/QIDS | x | x | x | |||

| Quality of life | AQol-6D/EQ-5D-5L | x | x | x | |||

| Pain intensity | Numerical rating scale | x | x | x | |||

| Pain-related disability | ODI | x | x | x | |||

| Pain self-efficacy | PSEQ | x | x | x | |||

| Work capacity | SPE | x | x | x | |||

| Measurements for the economic evaluation | |||||||

| Costs | TiC-P | x | x | ||||

| Quality of life | AQol-6D/EQ-5D-5L | x | x | x | |||

| Covariates | |||||||

| Demographic variables | SRQ/MR | x | x | ||||

| Depression type and chronicity | SCID | x | x | x | |||

| Prior depression treatment | TI | x | x | ||||

| Back pain type and chronicity | MR | x | x | ||||

| Internet affinity | IAS | x | x | ||||

| Patient adherence* | Attrition rate | x | x | ||||

| Patient satisfaction* | CSQ-8 | x | |||||

| Negative effects of the intervention | INEP/SRQ/TI/SReC | x | |||||

*Intervention group only.

AQol-6D, Assessment of Quality of Life; CSQ-8, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; EQ-5D-5L, European Quality of Life scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IAS, Internet Affinity Scale; ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; INEP, Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects of Psychotherapy; MR, medical record; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSEQ, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire; QIDS, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview; SPE, Subjective Prognostic Employment Scale; SReC, self-report during treatment to the eCoach; SRQ, Self-Report Assessment Questionnaire, TI, telephone interview; TiC-P, Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness.

The exclusion of individuals with severe depression is due to ethical concerns and based on ICD-10 criteria for severe depression according to the German treatment guidelines for depression.33 A trained psychotherapist (HB, LS, EM or SaS) contacts the participant to initiate further actions when severe depression is classified. We invite participants with a depression severity of PHQ ≥5, who do not fulfil the criteria to participate, in a parallel conducted trial for CBP and subclinical depressive symptoms: eSano BackCare-D.34

Procedure on suicidal ideation

Participants who are currently suffering from suicidal ideation are identified by suicide screenings within the telephone interviews (SCID, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D35), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS36)) and questionnaires (PHQ-9) and potentially through communication with the eCoach or the study administration. Following a suicide protocol adapted from prior trials,37–39 we send an email with detailed information on available health services and the advice to seek professional help if participants report low suicidal ideation (HAM-D, QIDS or PHQ-9 item score=1). In case of moderate-to-high suicidal ideation during the assessments or any suicidal thoughts or intentions reported to an eCoach or the study administration, a trained psychotherapist from the study team (HB, LS, EM or SaS) contacts the participant and initiate further actions. In the case of suicidal ideation communicated to the eCoach, unblinding is regarded as permissible.

Intervention development

eSano BackCare-D is based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), systematic behavioural activation40–42 and problem solving.43 The depression-specific components are based on a prior IMI ‘GET.ON Mood Enhancer’, that has been evaluated in numerous RCTs in different samples37 44 45 and shown to be effective in lowering depressive symptoms in individuals with diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2 with an intention-to-treat (ITT) effect size of d=0.89 at 2 months post-treatment45 and d=0.83 at 6 months follow-up.46 We added CBP-relevant information, videos and audio clips, based on existing literature on psychological back pain treatment,47 48 our clinical experience and an existing IMI for chronic pain individuals based on acceptance and commitment therapy.49 50 Think-aloud interviews with five persons with CBP helped us to pilot validate the intervention and further improve its feasibility and acceptability before recruitment start. Access to the platform proceeds through a unique username password combination and is available on a 24/7 basis from all devices with internet access, however, optimised for PCs, notebooks and (large-screen) tablets. It is not possible to assess which device will be used by individual participants. Additionally, a text message coach is provided in eSano BackCare-D that is described below. All transferred data are secured via www.minddistrict.com based on ISO27001 and guidelines NEN7510.

Intervention content

eSano BackCare-D provides six minimally guided sessions with an estimated proceeding duration of 45–60 min each, developed to be processed weekly. Three optional sessions with back pain-specific topics (sleep, partnership and sexuality, returning to work) are available at the end of sessions 3 through 5. Two booster sessions following the intervention are offered to improve sustainability of intervention effects. Session-specific contents and homework assignments are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the sessions in eSano BackCare-D

| Session | Depression-specific topics | Back pain-specific topics | Assignments |

| 1 | Psychoeducational information about depression | Connection between back pain and depression Pain acceptance |

To write down medical history and set goals Homework assignment: mood diary |

| 2 | Behavioural activation Information on connection between behaviour and mood |

Worrying about back pain-related complications | To create an activity plan Homework assignment: to complete the activation plan. |

| 3 | Problem solving I Introduction in problem solving. Information on solvable and unsolvable problems |

To work with the six problem-solving steps based on own problems Homework assignment: to implement the problem-solving steps during the week |

|

| 4 | Problem solving II Information about techniques to reduce rumination. Introduction to mindfulness |

Rumination about back pain | To review the problem-solving steps and implement a technique to stop rumination Homework assignment: to practise and track mindfulness exercises |

| 5 | Behavioural activation, focus on physical activity and self-esteem. Connection between mood and movement | Physical activity and back pain. Connection between back pain and physical rest | To raise awareness of successes and strengths. To learn to value oneself Homework assignment: to implement physical activity in daily life |

| 6 | Plan for the future Collection of pleasant activities |

Conversation with a general practitioner | To improve patient-physician relationship Homework assignment: to implement positive activities and create a future plan |

| Additional (optional) sessions | |||

| a | Healthy sleep Information on sleep hygiene, sleep restriction and stimulus control |

To implement the 10 rules for healthy sleep into daily life | |

| b | Partnership and sexuality Information on communication skills, physical closeness and sexuality |

To implement communication skills and massage exercises in daily life | |

| c | Returning to the workplace Information on self-management and interpersonal competencies |

Fitness exercises at the workplace | To set priorities, to implement the six steps for problem solving at the workplace, and to review communication skills |

| Booster sessions (within 3 months after the regular sessions) | |||

| 7 | Summary: behavioural activation; review; pleasant activities; problem solving | To reflect on positive changes and update the activity plan; to practice the six steps for problem solving | |

| 8 | Summary of the key elements, behavioural activation | Choice of the intervention topics (1–6 above) | |

Session 1 provides psychoeducational information on depression, the interaction between CBP and depression as well as pain acceptance. Participants define their depression-related and CBP-related goals and get to know the mood diary as the homework assignment for the next week. In session 2, the concept of behavioural activation and the connection between pleasant activities and mood is introduced. Based on the principles of action planning and coping planning,51 52 participants create an individual list and schedule for completion of pleasant activities in the next few days. The main focus in sessions 3 and 4 is on the six-step plan to handle solvable problems and to better manage emerging issues, comparable to other studies.45 53–55 In addition, techniques to reduce rumination on unsolvable problems and the concept of mindfulness are introduced. Session 5 includes information and exercises on physical activity,42 a mindfulness exercise and techniques to strengthen self-esteem. The sixth session serves to assess intervention-related changes in mood and provides a list of additional treatment options. Participants are encouraged to create a plan for the future. At the end, they write a letter to themselves about specific goals for the next 4 weeks and choose the date of the next booster session (after 2, 4 or 6 weeks) that are developed to review what the participants have learnt in previous sessions and to provide motivation to maintain and expand learnt skills in the future.

The sleep session builds on an evidence-based IMI for insomnia, that is, GET.ON Recovery.56 57 As insomnia is a predictor and symptom of depression,58 participants learn about the principles of sleep hygiene, sleep restriction and stimulus control.59 The partnership and sexuality session provides communication skills and exercises for improving physical closeness and sexuality. In the returning to work session, participants receive information on self-management and interpersonal competences as well as exercises in problem solving and physical relaxation.

Text message coach

The text message coach in eSano BackCare-D automatically sends one supportive text message per day for the duration of 6 weeks as text message prompts have been shown to increase efficacy and adherence of IMIs.60–62 The contents include a) reminders to complete the weekly assignments, b) repetition of the content, and c) motivation enhancement components.

Guidance

Based on previous studies showing that guidance and reminders and strict deadlines seem to be important with regard to the respective primary outcomes and adherence in IMIs,20 63–65 the feedback manual of eSano BackCare-D provides instructions to remind, set deadlines and formulate standardised feedback for each session. Trained and supervised eCoaches (psychologists) serve as contact person and provide feedback within two work days after each completed session. Feedbacks are adapted to the participants' assignments and include positive reinforcement for completion of assignments and encouragement to proceed with the time spent on guidance will be approximately 60–100 min per participant.

Control condition

Participants have unrestricted access to TAU. All types of medical/psychological help received during the last 3 months are tracked at T0 and T2 with the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with mental illness.66

Proposed sample size/power calculations

The sample size calculation is based on the primary endpoint, the HAM-D score at post-treatment. According to the results of trials on online interventions for depression,20 a treatment effect (pooled effect size) of d=0.39 would be of clinical interest and is considered feasible for the type of treatment. On the basis of a two-sample t-test at two-sided significance level of 0.05, the study is planned to detect this effect with 80% power. This requires a sample of 105 individuals in each arm.

Assessments

Depression screening

Depressive symptoms are assessed by the PHQ-927 which is a well validated depression screening instrument that has also been evaluated to be delivered as online version,67 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 and 84% sensitivity and 72% specificity for major depression.68

Depression diagnosis

The 17-item HAM-D is the most widely used clinician-rated measure of depression severity and as such viewed as the gold standard for the assessment of depression severity. Additionally, we use the QIDS36, which assesses the severity of depressive symptoms, covering all criterion symptom domains of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) to diagnose a major depressive episode.31 32 Moreover, we use section A (affective syndromes) of the SCID31 as a comprehensive, structured interview designed to be used by trained interviewers for the assessment of mental disorders according to the definitions and criteria of DSM. It enables a reliable, valid and efficient assessment of depressive disorders.32 As an add-on to the SCID for DSM-IV, we use a German translation of the SCID-5-RV to allow for DSM-569 diagnoses as well.

Interviewers are trained and weekly supervised by a psychologist (LS, EM) and are blinded to randomisation condition. At the beginning of each interview, participants and interviewers will be reminded to keep blinding throughout the assessment. After an initial training session, a supervisor and the interviewers assess the same participant together, with comparison of results as follows: the inter-rater reliability (IRR) for the SCID, measured by Cohen’s kappa and the intraclass correlation (ICC) for the HAM-D and QIDS. An almost perfect Cohen’s kappa ≥0.8170 and an excellent ICC coefficient ≥0.7571 is considered as sufficient. Each interviewer is compared with trainers' rating (LS, EM) until the sufficient IRR values are met. Afterwards, the interviewers are compared with each other on a random basis to assess the IRR.

Primary outcome

Depression severity

Depression severity is the core patient-relevant outcome in trials among depressed individuals72 73 and is assessed by means of the clinician-rated HAM-D-1735; (see table 1) at post-treatment (T1) as part of the telephone interview. IRR of the SCID was reported to be high for IRR comparing telephone and face-to-face interviews.74

Secondary outcomes

Depression response and remission

HAM-D scores are used to determine depression response in accordance with the recommendations of Jacobson and Truax.75 Depression remission is assessed by means of the SCID as part of the telephone interviews.

Health-related quality of life

The AQoL-6D includes 20 items and 6 dimensions and is suitable for quality of life assessments and economic evaluations of health programme with good psychometric properties76 and α=0.89.77 We additionally obtain the most widely used quality of life assessment EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) as a basis for cost-utility analyses (CUA) with five health domains of importance to quality of life.78

Pain intensity

We use an 11-point numerical rating (0–10) of the worst, least and average pain during the last week and calculate the mean of the three scales. Additionally, we use a categorical rating of pain intensity (none, mild, moderate, severe).

Pain-related disability

We obtain the Oswestry Disability Index79 as a reliable (α=0.8680) and valid 10-item self-report questionnaire, sensitive to change in difficulties in completing activities of daily living.79

Pain self-efficacy

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a validated and reliable (internal consistency: α=0.93) 10-item instrument that assesses self-efficacy expectations related to pain.81

Work capacity

The Subjective Prognostic Employment Scale is a validated 3-item self-report questionnaire (sum score 0–3) with high internal consistency (rep (Guttman scaling)=0.9982).

Intervention adherence

The attrition rate (calculated using the percentage of individuals who no longer use the intervention, as assessed by their log in data) gives an estimate of the individuals’ intervention adherence.

Patient satisfaction

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; German: ZUF-8), optimised for the assessment of client satisfaction in IMIs (CSQ-8)83 84 is a validated eight-item instrument with high internal consistency (α=0.92).84 The adapted version for the assessment of client satisfaction in IMIs has shown to have high internal consistency in a range of studies (α=0.92–0.94)57 85 86 and to be associated with treatment adherence and outcome.

Negative effects of psychotherapy

We include different ways of monitoring serious adverse events (SAE) adapted from the National Institute for Health Research recommendations87 and Horigian et al,88 who give general principles and examples to help illustrate their definition of SAEs: participants' responses in interviews, reported SAEs to the eCoach and SAEs assessed by means of the Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects of Psychotherapy (INEP) during the online assessments.89 The INEP consists of 15 items assessing a range of common changes participants experienced in line with the intervention. Cronbach’s alpha is α=0.86.89 At the beginning of every session, participants are asked about adverse events and are also encouraged to report the events to their eCoach who monitors the SAEs and initiates further actions if needed.

Costs

We use the German version of the Cost Questionnaire ‘Trimbos Institute and Institute of Medical Technology Questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric Illness’ (TiC-P; 59), adapted for the German healthcare system by Nobis et al 39 and for CBP individuals by the present authors. The TiC-P allows assessment of all direct healthcare services received during the last 3 months. Moreover, direct non-medical costs (eg, travel costs) and indirect costs are assessed, including the number of ‘work loss’ days (absenteeism), the number of ‘work cut-back’ days (presentism) and costs associated with domestic tasks.

Covariates

Demographic variables, prior depression treatments and internet affinity level are assessed by patient self-report, see table 1. We use the German version of the Internet Affinity Scale by Haase et al 90 to assess familiarity with the internet. Depression type (major depression yes/no), baseline severity and depression chronicity are assessed by the SCID, back pain type, severity and chronicity are extracted from medical records.

Statistical analysis

Clinical analyses

The primary outcome will be analysed with the HAM-D score at T1 as dependent variable and baseline value as covariates, adjusting for sex and age. Continuous secondary outcomes will be analysed accordingly. Standardised mean differences and 95% CIs will be calculated to measure the between-group effect size at post-treatment and follow-up. Additionally, clinical significance analyses, such as number needed to treat will be conducted. All analyses will be performed on an ITT principle with multiple imputations to replace missing data.91 Completer analyses (per-protocol) will be conducted to investigate the influence of study attrition on study results. Rates of patient-reported adverse events will be compared.

Economic evaluation

We will conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and a CUA. Outcome estimates will be the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and the incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR) after 6 months. A CEA with depression response as clinical outcome will be conducted. The generic outcome for the CUA will be quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which will be based on the AQoL-6D76 and in a sensitivity analysis based on the EQ-5D-5L.78 Both analyses will be conducted from a societal perspective including all direct and indirect costs. Non-parametric bootstrapping will be used to take into account stochastic uncertainty of the ICER. Furthermore, we will calculate a cost-acceptability curve to test the likelihood that the intervention is cost-effective relative to TAU, given varying threshold for the willingness to pay for one depression response or QALY gained, respectively.

Ethics and dissemination

All procedures are approved by the ethics committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-University of Freiburg and the data security committee of the German Pension Insurance (Deutsche Rentenversicherung). The trial has been registered prior to recruitment start at the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform via the German Clinical Studies Trial Register (DRKS): (DRKS00009272).

We conduct and report the RCT in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 Statement,92 the supplement of the CONSORT statement for pragmatic effectiveness trials92 93 and current guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research 28 94. The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented on international conferences.

Quality assurance and safety

The Clinical Trials Unit Freiburg performs monitoring visits to the participating clinic centres before, during and after completion of the study to ensure that the study is conducted, recorded and reported according to the study protocol, relevant standard operating procedures and requirements of the sponsor and/or the Ethic Committees in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH -GCP, http://ichgcp.net/). Rigorous operating procedures for data management and safety have been implemented. The principal investigator and the research assistants have access to the source data that will be kept for as long as the study takes until 10 years after completion.

Furthermore, an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) consisting of two experienced scientists and psychotherapists (MHä, MHa) and one statistician (LK) with long-standing experience in clinical trials has been established. The function of the DSMB is to monitor the course of the study and, if necessary, to give recommendations to the steering committee for discontinuation, modification or continuation of the study.

Discussion

The present effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial focusses on individuals with CBP and comorbid depression as two of the most frequent, most disabling health conditions with high associated economic burden.5 94

The WARD-BP trial is innovative in several ways: (a) studies examining the effectiveness of psychological depression interventions are regularly methodologically limited as they lack diagnostic clarification of depression status.20 73 93 By carrying out the SCID and HAM-D prior to randomisation and at follow-up assessments, the present trial will be the first trial on a psychological depression intervention for people with chronic pain with verified DSM diagnosis of depression; (b) with a target sample of 210 participants, the study will be optimally powered, overcoming limitations of small scale trials on psychological depression interventions in the medically ill12 73 93; (c) the eSano BackCare-D intervention is tailored to the special needs of the target group of patients with CBP. This has been discussed to have an uptake and adherence facilitating effect,95 likely to improve the effectiveness of online interventions; (d) the implementation of the intervention into the healthcare system overcomes one of the main criticisms regarding IMI trial being only representative for a selective online population96 97; (e) the current trial design will allow examination of the reach of this IMI and will provide valuable information about which CBP individuals are willing to use such interventions. With the use of two different recruitment strategies, we will be able to compare two different ways of implementing IMIs into clinical routine. This will allow for conclusions on feasible ways of improving the adherence and uptake of IMIs in respective target populations98–100; (f) finally, as one of still few clinical trials on psychological depression interventions the present trial comprises a CEA.

If the results of WARD-BP indicate that eSano BackCare-D is effective and cost-effective, its clinical impact on depression healthcare services could be substantial. When implemented as part of the standard healthcare, IMIs have the potential to reduce the ‘lost in transition phenomenon’ caused by fragmented healthcare systems.26 101 102 Engaging individuals in treatment at the interface of different healthcare sectors, as in the present (cost-)effectiveness trial, will contribute important information on potential approaches to improve the delivery of mental healthcare and at the same time provide insights on possible ways of implementing depression IMIs into care for CPB in order to exploit their full potential. The first results of WARD-BP are expected in 2018.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kristin Kieselbach and Professor Dr Anja Göritz for their support with providing their expertise in the content of the intervention. The authors thank colleagues who were part of the development of prior interventions that partly build the basis of eSano BackCare-D. Moreover, the authors like to thank our study assistants and interns and students for their support in the development of the intervention and in conducting the study. The authors thank Ellen Meierotto for supervising the SCID interviewers. Many thanks go to the Data Safety and Monitoring Board, consisting of Professor Dr Martin Hautzinger, Professor Dr Martin Härter and Dr Levente Kriston as well as the Clinical Trials Unit Freiburg for their support in carrying out the study project. Special thanks go to the eight orthopaedic clinics Schoen Klinik, Bad Staffelstein; RehaklinikSonnhalde, Donaueschingen; RehaKlinikum Bad Säckingen; Städt. Rehakliniken Bad Wald-see; Schwarzwaldklinik Orthopädie - Abteilung Medizinische Rehabilitation, Bad Krozingen; Rheintalklinik Bad Krozingen; REGIO-Reha Tagesklinik, Freiburg and Universitäts- und Rehabilitationskliniken, Ulm as well as the further orthopaedic rehabilitation units of the second recruitment strategy. The authors are very grateful to Mary Wyman for proofreading and language editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HB, DE, MB, OM and HR initiated this study. All authors contributed to the design of this study. HB, LS, SP, DE, SaS, DL, SN, JB, HR, MB and JL developed the intervention content eSano BackCare-D is based on as well as the assessment. HB, LS, SP, SaS, DE and JL are responsible for recruitment. SaS is responsible for randomisation and allocation as well as the administration of participants. JL wrote the draft of the manuscript. HB provided expertise on depression, CBP and psychological pain interventions. All authors contributed to the further writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (project: effectiveness of a guided web-based intervention for depression in back pain rehabilitation aftercare, grant number: 01GY1330A). This funding source has no influence on the design of this study and will not influence its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data or decision to submit results.

Competing interests: JL, LS, SP, SS, JB, SN, OM, HR and HB report no conflict of interest. DE, MB and DL are stakeholders of the ’Institute for Online Health Trainings', a company aiming to transfer scientific knowledge related to the present research into routine healthcare. A committee of independent scientists has been formed (Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB)) to supervise study-related decisions and prevent any influence of a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of the Albert- Ludwigs-University of Freiburg.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028–37. 10.1002/art.34347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med 2011;9:90 http://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/ 10.1186/1741-7015-9-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, et al. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2433–45. 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumeister H, Knecht A, Hutter N. Direct and indirect costs in persons with chronic back pain and comorbid mental disorders–a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2012;73:79–85. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumeister H, Balke K, Härter M. Psychiatric and somatic comorbidities are negatively associated with quality of life in physically ill patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:1090–100. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J, et al. Quality of life in medically ill persons with comorbid mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom 2011;80:275–86. 10.1159/000323404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nicholas MK, Coulston CM, Asghari A, et al. Depressive symptoms in patients with chronic pain. Med J Aust 2009;190:S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miles CL, Pincus T, Carnes D, et al. Can we identify how programmes aimed at promoting self-management in musculoskeletal pain work and who benefits? a systematic review of sub-group analysis within RCTs. Eur J Pain 2011;15:775.e1–775.e11. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007407 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoffman BM, Papas RK, Chatkoff DK, et al. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychol 2007;26:1–9. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumeister H, Härter M. Psychische Komorbidität bei muskuloskelettalen Erkrankungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2011;54:52–8. 10.1007/s00103-010-1185-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parker JC, Smarr KL, Slaughter JR, et al. Management of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a combined pharmacologic and cognitive-behavioral approach. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:766–77. 10.1002/art.11459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2428–9. 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:2099–110. 10.1001/jama.2009.723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, et al. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2:CD010152 10.1002/14651858.CD010152.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buhrman M, Gordh T, Andersson G. Internet interventions for chronic pain including headache: a systematic review. Internet Interv 2016;4:17–34. 10.1016/j.invent.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ebert DD, Zarski AC, Christensen H, et al. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119895 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sander L, Rausch L, Baumeister H. Effectiveness of internet-based interventions for the prevention of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment Health 2016;3:e38 10.2196/mental.6061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards D, Richardson T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:329–42. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2010;5:e13196 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016;12:157–79. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andersson G, Carlbring P, Cuijpers P. Internet interventions: moving from efficacy to effectiveness. E J Appl Psychol 2010;5(2): 18–24. 10.7790/ejap.v5i2.169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American college of physicians-society of general internal medicine-society of hospital medicine-American geriatrics society-American college of emergency physicians-society of academic emergency medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:971–6. 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ebert D, Tarnowski T, Gollwitzer M, et al. A transdiagnostic internet-based maintenance treatment enhances the stability of outcome after inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2013;82:246–56. 10.1159/000345967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim CS, Flanders SA. In the Clinic. Transitions of care. Ann Intern Med 2013;158(5 Pt 1):ITC3–1. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-01003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, et al. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord 2004;81:61–6. 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH Group. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e126 10.2196/jmir.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT Statement for Randomized Trials of Nonpharmacologic Treatments: A 2017 Update and a CONSORT Extension for Nonpharmacologic Trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:40 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:e1–e37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. User’s guide for the Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version: American Psychiatric Pub, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Fydrich T. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33. DGPPN BÄ, KBV A, AkdÄ B, et al. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinieUnipolare Depression-Langfassung. 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sander L, Paganini S, Lin J, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a guided Internet- and mobile-based intervention for the indicated prevention of major depression in patients with chronic back pain-study protocol of the PROD-BP multicenter pragmatic RCT. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:36 10.1186/s12888-017-1193-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56–62. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:573–83. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ebert DD, Lehr D, Baumeister H, et al. GET.ON Mood enhancer: efficacy of Internet-based guided self-help compared to psychoeducation for depression: an investigator-blinded randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:39 10.1186/1745-6215-15-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Evaluating the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of web-based indicated prevention of major depression: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:25 10.1186/1471-244X-14-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nobis S, Lehr D, Ebert DD, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a web-based intervention with mobile phone support to treat depressive symptoms in adults with diabetes mellitus type 1 and type 2: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:306 10.1186/1471-244X-13-306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:318–26. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression: procedures, principles, and progress. Clin Psychol Rev 2003;23:699–717. 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2007;22:9–15. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buntrock C, Ebert D, Lehr D, et al. Effectiveness of a web-based cognitive behavioural intervention for subthreshold depression: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:348–58. 10.1159/000438673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nobis S, Lehr D, Ebert DD, et al. Efficacy of a web-based intervention with mobile phone support in treating depressive symptoms in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2015;38:776–83. 10.2337/dc14-1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ebert DD, Nobis S, Lehr D, et al. 6-months effectiveness of internet-based guided self-help for diabetes and comorbid depression. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med;34:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martin A, Härter M, Henningsen P, et al. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinie zur Psychotherapie somatoformer Störungen und assoziierter Syndrome: Hogrefe Verlag, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kröner-Herwig B. Rückenschmerz: Hogrefe Verlag, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin J, Paganini S, Sander L, et al. An Internet-based intervention for chronic pain—a three-arm randomized controlled study of the efficacy of guided and unguided commitment and acceptance therapy. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2017;41:681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin J, Lüking M, Ebert DD, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a guided and unguided internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: Study protocol for a three-armed randomised controlled trial. Internet Interv 2015;2:7–16. 10.1016/j.invent.2014.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krämer LV, Helmes AW, Bengel J. Understanding activity limitations in depression: Integrating the concepts of motivation and volition from health psychology into clinical psychology. Eur Psychol 2014;19:278 http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/epp/19/4/278/ [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krämer LV, Helmes AW, Seelig H, et al. Correlates of reduced exercise behaviour in depression: the role of motivational and volitional deficits. Psychol Health 2014;29:1206–25. 10.1080/08870446.2014.918978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, et al. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e44 10.2196/jmir.1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N. Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e7 10.2196/jmir.954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ebert DD, Lehr D, Boß L, et al. Efficacy of an internet-based problem-solving training for teachers: results of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40:582–96. 10.5271/sjweh.3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thiart H, Lehr D, Ebert DD, et al. Log in and breathe out: internet-based recovery training for sleepless employees with work-related strain - results of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health 2015;41:164–74. 10.5271/sjweh.3478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ebert DD, Berking M, Thiart H, et al. Restoring depleted resources: Efficacy and mechanisms of change of an internet-based unguided recovery training for better sleep and psychological detachment from work. Health Psychology 2015;34:1240–51. 10.1037/hea0000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135:10–19. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia:update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep 2006;29:1398–414. 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e4 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, et al. Internet interventions: in review, in use, and into the future. Prof Psychol 2003;34:527–34. 10.1037/0735-7028.34.5.527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e16 10.2196/jmir.1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Almlöv J, Carlbring P, Berger T, et al. Therapist factors in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for major depressive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2009;38:247–54. 10.1080/16506070903116935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kleiboer A, Donker T, Seekles W, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the role of support in Internet-based problem solving therapy for depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2015;72:63–71. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, et al. The impact of guidance on internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interv 2014;1:205–15. 10.1016/j.invent.2014.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hakkaart-Van Roijen L, van Straten A, Donker M, et al. Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness (TIC-P): Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Trimbos, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Erbe D, Eichert H-C, Rietz C, et al. Interformat reliability of the patient health questionnaire: validation of the computerized version of the PHQ-9. Internet Interv 2016;5:1–4. 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fleiss JL, The Design and analysis of clinical experiments. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Baumeister H, Hutter N. Collaborative care for depression in medically ill patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012;25:405–14. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283556c63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD008012 10.1002/14651858.CD008012.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Crippa JA, de Lima Osório F, Del-Ben CM, et al. Comparability between telephone and face-to-face structured clinical interview for DSM-IV in assessing social anxiety disorder. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2008;44:241–7. 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Richardson JR, Peacock SJ, Hawthorne G, et al. Construction of the descriptive system for the Assessment of Quality of Life AQoL-6D utility instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:38 10.1186/1477-7525-10-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Allen M, Iezzoni LI, Huang A, et al. Improving patient-clinician communication about chronic conditions: description of an internet-based nurse E-coach intervention. Nurs Res 2008;57:107–12. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313478.47379.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mannion AF, Junge A, Grob D, et al. Development of a German version of the Oswestry disability index. Part 2: sensitivity to change after spinal surgery. Eur Spine J 2006;15:66–73. 10.1007/s00586-004-0816-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wittink H, Turk DC, Carr DB, et al. Comparison of the redundancy, reliability, and responsiveness to change among SF-36, Oswestry disability index, and multidimensional pain inventory. Clin J Pain 2004;20:133–42. 10.1097/00002508-200405000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;11:153–63. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mittag O, Raspe H. [A brief scale for measuring subjective prognosis of gainful employment: findings of a study of 4279 statutory pension insurees concerning reliability (Guttman scaling) and validity of the scale]. Rehabilitation 2003;42:169–74. 10.1055/s-2003-40095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Boß L, Lehr D, Reis D, et al. Reliability and validity of assessing user satisfaction with web-based health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e234 10.2196/jmir.5952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2:197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Thiart H, Lehr D, Ebert DD, et al. Log in and breathe out: efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an online sleep training for teachers affected by work-related strain–study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:169 10.1186/1745-6215-14-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ebert DD, Heber E, Berking M, et al. Self-guided internet-based and mobile-based stress management for employees: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:315–23. 10.1136/oemed-2015-103269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Duggan C, Parry G, McMurran M, et al. The recording of adverse events from psychological treatments in clinical trials: evidence from a review of NIHR-funded trials. Trials 2014;15:335 10.1186/1745-6215-15-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Horigian VE, Robbins MS, Dominguez R, et al. Principles for defining adverse events in behavioral intervention research: lessons from a family-focused adolescent drug abuse trial. Clin Trials 2010;7:58–68. 10.1177/1740774509356575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ladwig I, Rief W, Nestoriuc Y. Welche Risiken und Nebenwirkungen hat Psychotherapie? - Entwicklung des Inventars zur Erfassung Negativer Effekte von Psychotherapie (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie 2014;24:252–63. 10.1159/000367928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Haase R, Schultheiss T, Kempcke R, et al. Use and acceptance of electronic communication by patients with multiple sclerosis: a multicenter questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e135 10.2196/jmir.2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002;7:147–77. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD008381 10.1002/14651858.CD008381.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Recruiting participants for interventions to prevent the onset of depressive disorders: possible ways to increase participation rates. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:181–7. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Baumeister H. Kein signifikanter Zusatznutzen als Add-on in der allgemeinärztlichen Routineversorgung. InFo Neurologie & Psychiatrie 2016;18:14–15. 10.1007/s15005-016-1601-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Hewitt C, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015;351:h5627 10.1136/bmj.h5627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Baumeister H, Nowoczin L, Lin J, et al. Impact of an acceptance facilitating intervention on diabetes patients' acceptance of Internet-based interventions for depression: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;105:30–9. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ebert DD, Berking M, Cuijpers P, et al. Increasing the acceptance of internet-based mental health interventions in primary care patients with depressive symptoms. A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2015;176:9–17. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Baumeister H, Seifferth H, Lin J, et al. Impact of an acceptance facilitating intervention on patients' acceptance of internet-based pain interventions: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2015;31:528–35. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Calear AL, et al. Developing a roadmap for the translation of e-mental health services for depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015;49:776–84. 10.1177/0004867415582054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:533 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340(mar23 1):c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015226supp001.pdf (233KB, pdf)