Abstract

Objectives

To assess the demographic, behavioural, psychosocial and structural factors associated with non-utilisation of HIV testing and counselling (HTC) services by female sex workers (FSWs) and men who have sex with men/transgender (MSM/TG).

Methods

This study involved a cross-sectional design. We used the national surveillance survey data of 2012, which included 610 FSWs and 400 MSM/TG recruited randomly from 22 and three districts of Nepal, respectively. Adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) using modified Poisson regression was used to assess and infer the association between outcome (non-utilisation of HTC in last year) and independent variables.

Results

Non-utilisation of HTC in the last year was 54% for FSWs and 55% for MSM/TG. The significant factors for non-utilisation of HTC among FSWs were depression (aPR=1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.6)), injectable drug abuse (ever) (aPR=1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.8)), participation (ever) in HIV awareness programmes (aPR=1.2 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.4)), experience of forced sex in previous year (aPR=1.1 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.3)) and absence of dependents in the family (aPR=1.1 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.3)). Non-utilisation of HTC among MSM/TG had significant association with age 16–19 years (aPR=1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.7)), non-condom use (aPR=1.2 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.4)), participation (ever) in HIV awareness programmes (aPR=1.6 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.0)), physical assault in previous year (aPR=1.8 (95% CI 1.0 to 3.1)), experience of forced sex in previous year (aPR=0.5 (95% CI 0.3 to 0.9)).

Conclusion

Although limited by cross-sectional design, we found many programmatically relevant findings. Creative strategies should be envisaged for effective behavioural change communication to improve access to HIV testing. Psychosocial and structural interventions should be integrated with HIV prevention programmes to support key populations in accessing HIV testing.

Keywords: key populations, HIV voluntary testing and counselling, MSM, transgender, FSW, SORT IT, Nepal

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Psychosocial and structural factors were assessed for the first time in the national surveillance survey of 2012.

Social desirability bias and recall bias due to the assessment of past exposures might have influenced the self-reported variables.

The cross-sectional design of the study limits conclusion on causality.

Introduction

Globally, at the end of 2015, an estimated 36.7 million people were living with HIV, of which 47% did not know their HIV status and hence were deprived of antiretroviral therapy and care.1 According to UNAIDS 90-90-90 target, by 2020, 90% of all individuals living with HIV should know their HIV status, 90% of all individuals with diagnosed HIV infection should receive sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 90% of all individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy should have viral suppression. By 2030 the AIDS epidemic will no longer be a public health threat if these three targets are achieved.2

The key population are those who have a high risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Global studies have shown that key populations are 13–22 times more likely to be infected with HIV than the general population.3 The key population includes female sex workers (FSWs) and men who have sex with men (MSM)/transgender (TG).4 FSWs and MSM/TG are 13–14 times more likely to be infected with HIV than the general population.3

WHO recommended an integrated biological and behavioural surveillance (IBBS) survey to monitor HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among key populations. In the late 1990s, IBBS was started by the government of Nepal as part of a response plan against an HIV/AIDS epidemic.5 HIV testing and counselling (HTC) is the entry point for HIV care services in Nepal and is provided free of cost to all. HTC is a critical intervention in achieving the first 90, that is, people living with HIV should know their HIV status. Though the first step is crucial in identifying people living with HIV (PLHIV), the retention in care of PLHIV in the second 90 and third 90 is equally necessary to maximise the treatment and prevention benefits of antiretroviral therapy.6 7 National consolidated guidelines for preventing and treating HIV in Nepal had recommended various approaches for maximising HIV testing in facility- and community-based settings.4 5 Different surveillance surveys conducted in Nepal found that the non-utilisation of HTC was low, around 50% in FSWs and MSM/TG.8

There was a substantial decline in the proportion of FSWs visiting HTC in 2016 compared with 2012 as revealed by IBBS 2016.9 Among FSWs, a decreasing trend in HIV prevalence was accompanied by an increasing trend in lack of comprehensive knowledge regarding HIV.9 10 The UNAIDS target of 90% assessment of HIV status by 2020 might not be reached in Nepal unless factors associated with non-utilisation of HTC are identified and addressed.2 11 12

Psychosocial variables like distress/depression were included only in the IBBS 2012 survey and were found to be high (40–50%) in the key population studied (people who inject drugs, FSWs and MSM/TG).10 13 14 Different studies demonstrate that the psychosocial problems (depression, drug abuse and suicidality) increase the likelihood of HIV-related risk behaviours among FSWs and MSM/TG in Nepal.15 16 Studies conducted outside of Nepal (India and USA) among key populations (MSM/TG and FSWs) found that psychosocial (depression, substance abuse, violence) and structural factors not only increase their risk behaviours but also lower the uptake of behavioural interventions.17–19 The identification of effects of psychosocial and structural factors in the uptake of HTC would help us to improve existing challenges of reaching key populations in Nepal. However, such evidence is very limited in Nepal. Therefore, using the IBBS 2012 data, we aimed to determine the demographic, behavioural, psychosocial and structural risk factors associated with non-utilisation of HTC in the last year by FSWs and MSM/TG in Nepal.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional study involving secondary data of FSWs and MSM/TG collected from the IBBS survey of 2012 in Nepal.

Setting

Nepal, with a population of 27 million, is a low-income, beautiful landlocked country in Southeast Asia.20 It shares borders with China in the north and India to the south, east and west. Nepal is divided into 75 districts and consists of a Himalayan mountainous region in the north and open terrain (Terai in local language) in the south. The HTC service was first started in Nepal in 1995 by the National Programme for AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Disease. There are over 235 HTC service sites in Nepal as of July 2016.

HTC in Nepal

In Nepal, HTC is the entry point for HIV prevention and treatment services, the primary aim of which is to identify people living with HIV and link them to treatment. It is voluntary and provided free of cost. Health facilitators should maintain confidentiality and obtain informed consent during pre-test and post-test counselling. According to national guidelines, key populations are expected to visit HTC every 6–12 months.5 Besides that, community-based interventions are also prioritised in which peer educators and outreach workers are mobilised in the community. Peer educators are volunteers who convey crucial information (proper condom use, HIV testing, etc) to key populations in informal (cruising areas like bus parks or public parks) and formal settings (drop-in centres). They also distribute condoms, safe needles/syringes or make them aware about available treatment, care and support services.

IBBS 2012 survey, Nepal

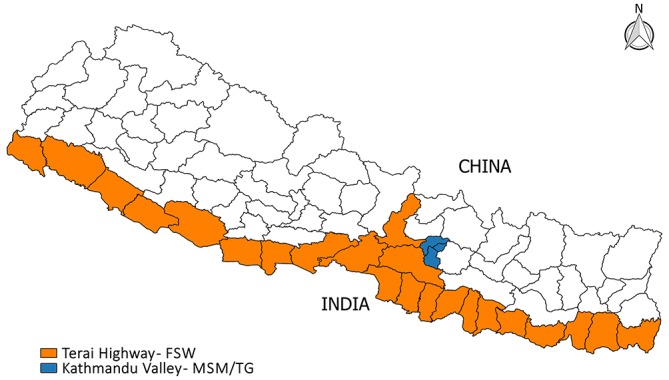

The National Centre for AIDS and STD Control (NCASC), Nepal conducted two separate cross-sectional IBBS surveys between September and November 2012 for FSWs and MSM/TG, respectively. FSWs were defined as ‘women aged 16 years and above reporting to have been paid in cash or kind for sex with a male within the last 6 months’. MSM/TG were defined as ‘men aged 16 years or above who have had sexual relations (either oral or anal) with another male in the 12 months preceding the survey’.7 A survey among FSWs was conducted in 22 Terai highway districts and for MSM/TG in three districts of Kathmandu valley (Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur)figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study districts included in the integrated biological and behavioural surveillance (IBBS) survey 2012, Nepal. FSW – female sex workers; MSM/TG – men who have sex with men/transgender.

Study population and sampling

The FSWs were recruited using two-stage cluster sampling: stage one was the selection of clusters, and stage two was the random selection of an equal number of participants from each selected cluster to ensure a self-weighted sample. A cluster was defined as having at least 30 sex workers in that area; those with fewer than 30 sex workers were merged with nearby locations to form a cluster. To identify clusters, mapping was performed with the support of local non-governmental organisations to determine areas where sex work is common and noting the estimated number of possible survey participants in each area. Seventy clusters out of a total of 401 clusters were selected based on probability proportionate to size (PPS).

The MSM were recruited using respondent-driven sampling (RDS)20 in three districts of Kathmandu valley. To begin with, a total of eight MSM/TG were recruited as seeds. Those seeds were informed about survey protocols and procedures, and were encouraged to randomly recruit other eligible individuals from their social networks to participate in the survey. These initial seeds were provided with three coupons to pass to their peers who were eligible to participate in the survey.

Detailed methodology and sampling strategies for IBBS surveys have been described previously.10 13–15

Data variables for the present study

The IBBS survey included information on behavioural factors like uptake of interventions for HIV, demographic, behavioural, psychosocial and structural variables.10 13 14 Structural factors included environmental/context conditions which were outside the control of the individual, but which could influence his/her perceptions, behaviour and health.21 Psychosocial variables (social support and depression) were assessed using the Social Support Questionnaire Short form (SSQS) and the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, respectively. The CES-D tool showed high reliability and validity in assessing depression in diverse groups such as PLHIV, women and MSM, with Cronbach’s α≥0.85 and comparative fit indices more than 0.90.22 The CES-D is an extensively normed and validated tool.23 Similarly the reliability and construct validity of the SSQS has been reported as high (>0.90) in different studies.24 25

A median score of <5 in theSSQS scale was interpreted as ‘dissatisfied with available social support’. CES-D scores of 16–21 and ≥22 were classified as distress and depression, respectively. We also assessed suicidality under psychosocial-related variables. Prevalence of demographic, behavioural, psychosocial and structural factors is summarised in supplementary web-only tables 1 and 2.

A self-reported visit to an HTC facility in the past year by FSWs and MSM/TG was chosen as the outcome variable. The outcome variable was assessed by asking ‘Have you visited (yes vs no) any HTC centres in the last 12 months?’ (Reasons for visiting: pre–post HIV/AIDS test counselling, information on HIV/AIDS window period, HIV test result, counselling on using condom correctly in each sexual intercourse). In addition to reasons above, discussion on safe injecting behaviour was also one of the self-reported reasons among people who inject drugs (PWID) for visiting HTC. The independent variables (demographic, behavioural, psychosocial and structural risk variables) selected in this study have been described in online supplementary web-only box 1.

bmjopen-2017-017408supp003.pdf (21.1KB, pdf)

Analysis and statistics

Data analysis was done separately for FSWs and MSM/TG. Data were analysed using STATA (version 12.1, STATA Corp., College Station, Teas, USA). Categorical variables were described using frequency and proportions. The unadjusted and adjusted analysis was performed separately for FSWs and MSM/TG to assess the association of factors with the outcome variable (not utilising HTC in last year). All the RDS-related descriptive outputs were adjusted to represent the structure of the study population (MSM/TG), which was based on information regarding who recruited whom, and the relative size of the respondent’s network using the Volz–Heckathorn estimator (RDS II).(20) To assess the network size among MSM/TG, the following question was asked: ’How many other MSM/TG do you know who also know you well? (Knowing someone is defined as being able to contact them and having had contact with them in the past 12 months)'. RDS-adjusted values are presented in the supplementary material (supplementary web-only tables 1 and 2). A convergence plot for outcome variables is also shown in the supplementary material (supplementary file web only figure 1). Adjustment for clustering of two-stage cluster sampling was not required for FSW data as it was a self-weighted sample.

bmjopen-2017-017408supp001.pdf (89.5KB, pdf)

Bivariate associations between each independent variable and non-utilisation of HTC were calculated using a variance inflation factor after assessment for multicollinearity. Variables with a p value <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included in the regression model (enter method). Adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by fitting a Poisson regression with robust variance estimates. The variables included in the multivariate model (aPR) for FSWs were age group, educational status, condom use at last sex, ever inject drugs, ever participated in HIV awareness programme, physical assault in last year, forced sex in last year, having dependents, police detention in last 6 months, stigma towards HIV and distress/depression. The variables included in the aPR for MSM/TG were age group, condom use at last sex, drinking alcohol, ever participated in HIV awareness programme, physical assault in last year, forced sex in last year, and discrimination in job and suicidal thought ‘ever’.

Initially, we used the log-binomial model to assess the association between independent and outcome variables of interest. However, the log-binomial model failed to converge. To overcome the effects of failed convergence, we used Poisson regression with robust variance estimates as recommended by Tyler et al.26 Poisson regression with robust variance can be used as an alternative to logistic regression and also provides accurate estimates in the cross-sectional study with a binary outcome of interest.27 We calculated the prevalence ratio because it was easier to interpret than the odds ratio. We also assessed associations between outcome and independent variables via the Poisson model using individualised RDS weights (online supplementary web-only table 3).

bmjopen-2017-017408supp005.pdf (113.8KB, pdf)

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for the IBBS survey 2012 was given by the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), Kathmandu, Nepal. Approval for the analysis of secondary data for this study was obtained in 2016 from the Ethics Advisory Group, the International UnionAgainst Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France. Administrative approval was also received from NCASC and Public Health and Environment Research Centre (PERC) Nepal. Waiver of informed consent was sought and approved by the ethics committee as this study involved analysis of secondary data.

Results

The IBBS survey 2012 included 610 FSWs with a response rate of 88.9%. The non-responders were replaced by other randomly selected FSWs of the same cluster. The HIV prevalence was 1% among FSWs. The proportion of FSWs in the age group 16–19 was 13.9%. The prevalence of non-utilisation of HTC in last year was 54% among FSWs. More than half of FSWs (59%) were married, 24% of them were divorced or separated. Two-thirds of FSWs (68%) were literate (table 1 and online supplementary web-only table 2).

Table 1.

Factors associated with non-utilisation of HIV testing and counselling (HTC) centres among female sex workers surveyed under the integrated biological and behavioural surveillance survey, 2012, Nepal

| Variables | Total | HTC not utilised† | Adj. PR‡ |

| N | n (%) | ||

| Total | 610 | 330 (54) | |

| Demographic | |||

| Age in years | |||

| 16–19 | 85 | 51 (60) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| 20–24 | 130 | 73 (56) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| >25 | 395 | 206 (52) | Ref. |

| Educational status | |||

| Illiterate | 196 | 98 (50) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) |

| Literate | 414 | 232 (56) | Ref. |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 360 | 197 (55) | Ref. |

| Unmarried | 102 | 60 (59) | – |

| Separated/divorced | 148 | 73 (49) | – |

| Having dependents | |||

| Yes | 341 | 169 (50) | Ref. |

| No | 269 | 161 (60) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3)* |

| Behavioural | |||

| Condom use at last sex | |||

| Yes | 461 | 256 (56) | Ref. |

| No | 149 | 74 (32) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) |

| Ever inject drugs | |||

| Yes | 40 | 29 (73) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8)* |

| No | 570 | 301 (53) | Ref. |

| Structural | |||

| Ever participated in HIV awareness programme | |||

| Yes | 169 | 102 (52) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4)* |

| No | 441 | 228 (60) | Ref. |

| Physical assault in last year | |||

| Yes | 81 | 36 (44) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) |

| No | 529 | 294 (56) | Ref. |

| Housing instability | |||

| Homeless | 15 | 6 (40) | – |

| Own home | 320 | 169 (53) | – |

| Rented | 275 | 155 (56) | |

| Forced sex in last year | |||

| Yes | 125 | 84 (67) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3)* |

| No | 485 | 246 (51) | Ref. |

| Police detention in last 6 months | |||

| Yes | 81 | 37 (46) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) |

| No | 529 | 293 (55) | Ref. |

| Client refusal to pay in last year | |||

| Yes | 153 | 89 (58) | – |

| No | 457 | 241 (53) | – |

| Psychosocial | |||

| Stigma towards HIV | |||

| Yes | 295 | 168 (57) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| No | 315 | 162 (51) | Ref. |

| Suicidal thoughts (ever) | |||

| Yes | 210 | 117 (56) | – |

| No | 399 | 212 (53) | – |

| Depression§ | |||

| Euthymic | 342 | 159 (46) | Ref. |

| Distressed | 156 | 100 (64) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.5)* |

| Depressed | 112 | 71 (63) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.6)* |

| SSQS | |||

| Satisfied | 530 | 289 (55) | – |

| Dissatisfied | 80 | 41 (51) | – |

*P<0.05.

†Not utilised in last 1 year.

‡Adjusted prevalence ratio (Adj. PR) using Poisson regression with robust variance estimates (enter method); factors with unadjusted PR with P<0.2 included in the model and collinearity checked.

§Depression measured using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale.

Ref., Reference category; SSQS, Social Support Questionnaire Short form.

bmjopen-2017-017408supp002.pdf (90.3KB, pdf)

The IBBS survey 2012 included 400 MSM/TG, and we did not record non-response among MSM/TG because of the nature of the sampling technique; that is, study participants enrol the other possible participants in the study. The HIV prevalence was 3.3% among MSM/TG. The proportion of MSM/TG in the age group 16–19 was 17.2%. Non-utilisation of HTC in last year was 55% for MSM/TG. The majority of MSM/TG were unmarried (72%) whereas very few of them were illiterate (3%). Other characteristics of the FSWs and MSM/TG are presented in online supplementary web-only tables 1 and 2.

The factors associated with non-utilisation of HTC in last year among FSWs and MSM/TG are summarised in table 1 and table 2, respectively. In the multivariable analysis, the association between non-utilisation of HTC and distress/depression remained significant. FSWs experiencing distress (aPR 1.4; 95% C 1.1 to 1.5) and depression (aPR 1.4; 95% C 1.1 to 1.6) were more likely not to use HTC in the past year. Similarly, FSWs who were injecting drugs (ever) (aPR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 1.8), ever participated in HIV awareness programmes (aPR 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.4), or had no dependents in the family (aPR 1.1; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.3) were more likely not to use HTC. FSWs who experienced forced sex (aPR 1.1; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.3) in the last 12 months were also more likely not to use HTC (table 1).

Table 2.

Factors associated with non-utilisation of HIV testing and counselling (HTC) centres among men having sex with men/transgender surveyed under the integrated biological and behavioural surveillance survey, 2012, Nepal

| Variables | N | HTC not utilised† | Adj. PR‡ |

| n (%)§ | |||

| Total | 400 | 221 (55) | |

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age in years | |||

| 16–19 | 69 | 54 (78) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7)* |

| 20–24 | 129 | 73 (57) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

| >25 | 202 | 94 (47) | Ref. |

| Educational status | |||

| Illiterate | 13 | 7 (54) | – |

| Literate | 387 | 214 (55) | – |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | 289 | 163 (56) | – |

| Married | 111 | 58 (52) | – |

| Behavioural | |||

| Condom use at last sex | |||

| Yes | 339 | 177 (72) | Ref. |

| No | 61 | 44 (52) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4)* |

| Drinking alcohol | |||

| Yes | 323 | 186 (58) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| No | 77 | 35 (45) | Ref. |

| Structural | |||

| Ever participated in HIV awareness programme | |||

| Yes | 185 | 62 (34) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0)* |

| No | 215 | 159 (74) | Ref. |

| Physical assault in last year | |||

| Yes | 57 | 10 (18) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.1)* |

| No | 343 | 211 (62) | Ref. |

| Housing instability | |||

| Homeless | 8 | 4 (50) | – |

| Own home | 75 | 42 (56) | – |

| Rented | 317 | 175 (55) | – |

| Forced sex in last year | |||

| Yes | 52 | 10 (19) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9)* |

| No | 348 | 211 (61) | Ref. |

| Discrimination in job | |||

| Yes | 79 | 17 (22) | Ref. |

| No | 321 | 204 (64) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) |

| Psychosocial factors | |||

| Stigma towards HIV | |||

| Yes | 253 | 138 (54) | – |

| No | 147 | 83 (56) | – |

| Suicidal thought ever | |||

| Yes | 107 | 33 (31) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) |

| No | 293 | 188(64) | Ref. |

| Depression¶ | |||

| Euthymic | 220 | 121 (59) | – |

| Distressed | 83 | 49 (53) | – |

| Depressed | 97 | 51 (55) | – |

| SSQS | |||

| Satisfied | 390 | 216 (55) | – |

| Dissatisfied | 10 | 5 (50) | – |

*P<0.05.

†Not utilised in last 1 year.

‡Adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) using Poisson regression with robust variance estimates (enter method); factors with unadjusted PR with P<0.2 included in model and collinearity checked.

§Unweighted descriptive statistics for RDS-weighted estimates, refer to online supplementary web-only table 3

¶Depression measured using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale.

RDS, respondent-driven sampling; SSQS, Social Support Questionnaire Short form.

MSM/TG who were adolescents aged 16–19 years (aPR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7) and experienced physical assault (aPR 1.8; 95% CI 1.0 to 3.1) were more likely not to use HTC. However, MSM/TG who experienced forced sex (aPR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.9) were less likely not to use HTC. MSM/TG who did not use a condom during their last sex (aPR 1.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.4) or participated in an HIV awareness programme (aPR 1.6; 95% CI 1.3 to 2.0) were more likely not to use HTC (table 2).

We also assessed the association between independent variables and outcome variable via a Poisson model using individualised RDS weights. However, not much variation was observed in the results of the weighted and unweighted analysis (online supplementary web-only table 3).

Discussion

In the IBBS 2012 survey, in addition to individual-level variables, psychosocial and structural factors were added. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the relation between psychosocial and structural factors with HTC non-utilisation among FSWs and MSM/TG in Nepal. The uptake of HTC was low (around 55%) among MSM/TG in Nepal, which is consistent with the findings of studies conducted in Assam and Andra Pradesh, India; Zhejiang province, China; and Bangkok, Thailand.28–31Our study also demonstrates a low level of uptake of HTC among key population in Nepal, which is even lower (33%) among key population of Manipur and Nagaland in India.32 The current scenario suggests that the low uptake of HTC among MSM/TG and FSWs not only challenges timely identification and referring them for treatment to improve their health, but also increases the risk of secondary transmission from HIV-infected MSM/TG and FSWs to their partners. Community-based HTC with different approaches (mobile testing and door-to-door testing, etc) that was found to be effective in increasing uptake of HTC and linking people to HIV care among MSM/TG and FSWs in other settings33 needs to be evaluated in the context of Nepal. Otherwise, the 90-90-90 targets prioritised to improve health and prevention of secondary HIV transmission will not be possible in Nepal. This study also found different risk factors for non-utilisation of HTC in the last year among FSWs and MSM/TG. They were demographic: late adolescents (MSM/TG), absence of dependent members (FSWs); behavioural: injectable drug abuse (FSWs) and no condom use at last sex (MSM/TG); structural: participation in HIV awareness programmes (FSWs and MSM/TG), forced sex in last year (risk factor among FSWs and protective factor among MSM/TG), physical assault in last year (MSM/TG); and psychosocial: being distressed/depressed (FSWs).

Psychosocial factors play an important role in health services utilisation.16 FSWs who were distressed or had depression (4 out of every 10) had a higher prevalence of non-utilisation of HTC. This could have resulted in disempowerment and resulted in not accessing HTC services when needed.13 14 Studies have found that FSWs used alcohol and drugs to reduce stress and to help them cope with their work.17 34 A Gambian study showed that women who experienced forced sex reported severe depression.35 A study conducted among FSWs working outside of the capital city (Kathmandu) found a very high prevalence of depression, and the experience of any form of violence (verbal, physical or sexual) was also common and associated with depression.36 Currently, there are no targeted programmes to address the mental health problems of FSWs in Nepal and the lack of laws that protect the rights of sex workers also exacerbates the experience of violence among them. Efforts to address violence and its consequences (depression) among FSWs are essential in Nepal otherwise it will be difficult to increase uptake of HTC among them.

According to the IBBS survey of 2012, older MSM/TG were found to use condoms more often compared with younger MSM/TG. Similarly, the median age of first sexual intercourse being 16 years and the fact that older adolescent MSM/TG (16–19 years) did not significantly access HTC are causes of concern.10 13 The risk-taking behaviour in adolescents can compound their risk of acquiring HIV, and therefore this group needs to be targeted. In Nepal, the blanket approach to implementing interventions (HTC) without considering the specific needs of adolescents or young people belonging to key populations might have an impact on the low uptake of HTC. Evidence from China suggests that the use of a peer-led community-based rapid HIV test increases the uptake of HIV testing among young MSM.37

Not visiting an HTC facility was also associated with not using a condom during last sex among MSM/TG. FSWs who were injecting drugs were also less likely to use HTC in the last 12 months. Our study findings are consistent with the study conducted among FSWs in Vietnam where unprotected sex and injecting drug use were associated with a lower likelihood of having a voluntary HIV test.38 The findings suggest that we are failing to reach those FSWs who are at increased risk of HIV due to their dual risky behaviours, such as unprotected sex or injecting drugs.

Some factors affecting utilisation of HTC by MSM/TG were different from those of FSWs. Events like forced sex in the last year among FSW reduced the utilisation of HTC among FSWs. Among MSM/TG, the experience of forced sex led to the utilisation of HTC. The difference might be due to the fact that MSM/TG are a more highly networked population than FSWs39; most of them are directly or indirectly associated with their community organisations (Blue Diamond Society), which work for the rights of gender and sexuality minorities in Nepal. That may have resulted in MSM/TG seeking available services after experiencing sexual abuse.

Participation in HIV awareness programmes by key populations has shown a decreasing trend over the years.10 13 Participation as a risk factor for non-utilisation of HTC for both FSWs and MSM/TG is intriguing. The activities which enlisted more participation were short duration events like condom/AIDS day celebration compared with effective training methods like demonstration classes, workshops, and so on (online supplementary web only table 2). These aforementioned short-term awareness activities might not affect the knowledge levels of FSWs and MSM/TG about the importance of HTC. The other explanation for this could be the cross-sectional nature of the data. Those who had visited HTC in the last year might not have felt the need for attending HIV awareness programmes.

Despite being limited by a cross-sectional design, the findings of this study bring out three significant policy implications. First, the intervention to address the burden of depression needs to be an integral part of programmes for FSWs and MSM/TG at all levels. Second, HTC should be developed as an empowerment centre or training to improve the skills that help FSWs and MSM/TG to tackle physical and sexual abuse. Third, specific prevention programmes should be rolled out to reach adolescent FSWs and MSM/TG, and FSWs who are practising dual risk behaviours such as inconsistent condom use or injecting drug use. The HTC centre should also consider the specific needs of adolescent FSWs or MSM/TG.

Our study adhered to STROBE guidelines for conduct and reporting of the study.40 The findings are generalisable to FSWs and MSM/TG of Nepal as a standard sampling strategy was followed for the IBBS survey.10 13–15 The present study had inherent limitations of analysing secondary data. Certain pertinent variables (for example, injectable drug abuse in the last 12 months among MSM/TG) could not be included in the analysis due to missing data. The limitations of the original survey like social desirability bias and recall bias due to the assessment of past exposures might have influenced the self-reported variables. The cross-sectional design may result in difficulties in ascertaining temporality between various factors studied and non-utilisation of HTC.

Conclusion

To conclude, psychosocial and structural factors are influencing the utilisation of HIV testing and counselling centres among FSWs and MSM/TG in Nepal. In addition to focusing on these risk factors, there is a need to improve HTC to provide psychosocial support or to address the needs of specific adolescent FSWs and MSM/TG or FSWs who also inject drugs. Creative behaviour change and communication strategies or interventions to improve the skills to tackle physical and sexual abuse should be implemented to overcome the limitations of current programmes for key populations in Nepal.

bmjopen-2017-017408supp004.jpg (134.7KB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The specific SORT IT programme which resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by: The Union South-East Asia Office, New Delhi, India; the Centre for Operational Research, The Union, Paris, France; The Union, Mandalay, Myanmar; the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), MSF Brussels Operational Center, Luxembourg; Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India; Department of Community Medicine, Government T.D. Medical College, Alappuzha, India; College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Exeter University, UK; Velammal Medical College Hospital & Research Institute, Madurai, India; and Institute of Medicine, University of Chester, UK.

Footnotes

Contributors: RS, SP, HDS and KD were involved in conception and design of the study; all authors were involved in analysis and interpretation of data; RS prepared the first draft, and all authors were involved in critically reviewing the draft and approving the final draft for submission.

Funding: All the IBBS survey-related activities were funded by The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM). This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the corresponding author and will be provided on request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. HIV factsheet. 2015.

- 2. UNAIDS. 90-90-90 an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS. 2013. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results impact and opportunities. Geneva: WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Review of the national HIV surveillance system: strengthening the HIV second generation surveillance in Nepal. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. National consolidated guidelines for treating and preventing HIV in Nepal. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. . The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793–800. 10.1093/cid/ciq243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koirala S, Deuba K, Nampaisan O, et al. . Facilitators and barriers for retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in Asia-A study in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Lao, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines and Vietnam. PLoS One 2017;12:1–20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Factsheet HIV epidemic update of Nepal, as of Dec 2015. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) survey among female sex workers in 22 terai highway districts of Nepal Round V. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) Survey among Men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender (TG) people in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization. Preventing HIV/AIDS in young people: a systematic review of the evidence from developing countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006, WHO Technical Report No: 938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lightfoot M. HIV prevention for adolescents: where do we go from here? Am Psychol 2012;67:661–71. 10.1037/a0029831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey (IBBS) among Male Injecting Drug Users (IDUs) in Western to Far Western Terai of Nepal. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Centre for AIDS And STD Control. Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) survey among Female sex workers in 22 Terai highway districts of Nepal. Kathmandu: National Centre for AIDS And STD Control, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deuba K, Anderson S, Ekström AM, et al. . Micro-level social and structural factors act synergistically to increase HIV risk among Nepalese female sex workers. Int J Infect Dis 2016;49:100–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deuba K, Ekström AM, Shrestha R, et al. . Psychosocial health problems associated with increased HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men in Nepal: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 2013;8:e58099 10.1371/journal.pone.0058099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. . Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2003;93:939–42. 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, et al. . Substance use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69(Suppl 2):1–15. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel SK, Saggurti N, Pachauri S, et al. . Correlates of mental depression among female sex workers in Southern India. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:809–19. 10.1177/1010539515601480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Volz E, Heckathorn D. Probability based estimation theory for respondent-driven sampling. J Offic Stat 2008;24:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21. UNAIDS. Combination HIV Prevention: tailoring and coordinating biomedical behavioural and structural strategies to reduce new HIV infections UNAIDS; Geneva, Switzerland, 2010:36. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Natamba BK, Achan J, Arbach A, et al. . Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale in screening for depression among HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal services in northern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:303 10.1186/s12888-014-0303-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, et al. . Relationships between stigma, social support, and depression in HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2010;21:144–52. 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yi MS, Mrus JM, Wade TJ, et al. . Religion, spirituality, and depressive symptoms in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williamson T, Eliasziw M, Fick GH. Log-binomial models: exploring failed convergence. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2013;10:14 10.1186/1742-7622-10-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jha UM, Raj Y, Venkatesh S, et al. . HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in India: national scenario of an unfinished agenda. Hiv Aids 2014;6:159–70. 10.2147/HIV.S69708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li R, Pan X, Ma Q, et al. . Prevalence of prior HIV testing and associated factors among MSM in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1152 10.1186/s12889-016-3806-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dandona R, Dandona L, Kumar GA, et al. . HIV testing among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS 2005;19:2033–6. 10.1097/01.aids.0000191921.31808.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vutthikraivit P, Lertnimitr B, Chalardsakul P, et al. . Prevalence of HIV testing and associated factors among young men who have sex with men (MSM) in Bangkok, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 2014;97(Suppl 2):S207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ganju D, Ramesh S, Saggurti N. Factors associated with HIV testing among male injecting drug users: findings from a cross-sectional behavioural and biological survey in Manipur and Nagaland, India. Harm Reduct J 2016;13:21 10.1186/s12954-016-0110-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. . Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001496 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Go VF, Srikrishnan AK, Parker CB, et al. . High prevalence of forced sex among non-brothel based, wine shop centered sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Behav 2011;15:1477–90. 10.1007/s10461-010-9758-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sherwood JA, Grosso A, Decker MR, et al. . Sexual violence against female sex workers in the Gambia: a cross-sectional examination of the associations between victimization and reproductive, sexual and mental health. BMC Public Health 2015;15:270 10.1186/s12889-015-1583-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sagtani RA, Bhattarai S, Adhikari BR, et al. . Violence, HIV risk behaviour and depression among female sex workers of eastern Nepal. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002763 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan H, Zhang R, Wei C, et al. . A peer-led, community-based rapid HIV testing intervention among untested men who have sex with men in China: an operational model for expansion of HIV testing and linkage to care. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:388–93. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xuan Tran B, Thanh Nguyen L, Phuong Nguyen N, et al. . HIV voluntary testing and perceived risk among female sex workers in the mekong delta region of vietnam. Glob Health Action 2013;6:20690–7. 10.3402/gha.v6i0.20690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deuba K, Ojha B, Shrestha R, et al. . Optimizing the implementation of integrated biological and behavioural surveillance surveys of HIV in resource limited settings-lessons from Nepal. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2014;4:S605–15. 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60688-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017408supp003.pdf (21.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017408supp001.pdf (89.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017408supp005.pdf (113.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017408supp002.pdf (90.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017408supp004.jpg (134.7KB, jpg)