Abstract

Objectives

Older adults frequently visit the emergency department (ED). Socioeconomic status (SES) has an important impact on health and ED utilisation; however, the association between SES and ED utilisation in elderly remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between SES in older adult patients visiting the ED on outcomes.

Design

A retrospective study.

Participants

Older adults (≥65 years) visiting the ED, in the Netherlands. SES was stratified into tertiles based on average household income at zip code level: low (<€1800/month), intermediate (€1800–€2300/month) and high (>€2300/month).

Primary outcomes

Hospitalisation, inhospital mortality and 30-day ED return visits. Effect of SES on outcomes for all groups were assessed by logistic regression and adjusted for confounders.

Results

In total, 4828 older adults visited the ED during the study period. Low SES was associated with a higher risk of hospitalisation among community-dwelling patients compared with high SES (adjusted OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7). This association was not present for intermediate SES (adjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.4). Inhospital mortality was comparable between the low and high SES group, even after adjustment for age, comorbidity and triage level (low OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.8 to 2.6, intermediate OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.8 to 2.2). Thirty-day ED revisits among community-dwelling patients were also equal between the SES groups (low: adjusted OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.4, and intermediate: adjusted OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.1).

Conclusion

In older adult ED patients, low SES was associated with a higher risk of hospitalisation than high SES. However, SES had no impact on inhospital mortality and 30-day ED revisits after adjustment for confounders.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, elderly, emergency department

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the few studies to provide detailed insight into the impact of different socioeconomic status groups of older adults in the emergency care.

Additionally, in this study, the living situation was used to differentiate between community-dwelling patients and institutionalised patients to observe differences in outcomes.

This study used a retrospective cohort study and linked patient zip code with income data based on a well-defined database by Statistics Netherlands.

A strength of our study is that we investigated a large undifferentiated group of older adult emergency care patients.

Limitations were that we were not able to extract the data of cardiology and gynaecology patients and that we used zip code to define the socioeconomic status.

Introduction

The burden on the emergency department (ED) capacity has been increasing over the past decades, which is mostly due to a substantially increasing number of older adults (≥65 years old).1 Given the extent and complexity of the problems in these patients, it is essential to identify determinants that lead to the ED visits in order to maintain high quality of care of older adult ED patients.2

Low socioeconomic status (SES) has already been identified as an important determinant of health status and is strongly associated with poor adverse health outcomes.3 Patients with a low SES visit the general practitioner (GP) more and the specialist less often than patients with a high SES.4 5 Moreover, patients with a low a SES use the ED more frequently and are admitted to the hospital more often than those with a high SES.4 6–10 However, most studies focused on the influence of SES on the quantity of ED utilisation, rather than on the reasons for and outcomes of these ED visits in general.8 10–12

It is well known that older adults are vulnerable and prone to adverse health outcomes, such as ED visits, ED return visits, hospitalisation and mortality.13 However, research on the effect of SES on ED visits and adverse health outcomes in these older adults is scarce.10 14 15 Some of these studies demonstrated conflicting results as where low SES patients showed higher risk of adverse health outcomes,8 16 17 while other studies did not find such an increased risk.11 12 18 Moreover, most studies focused on patients with a specific diagnosis (eg, heart failure, pneumonia or injury) and other studies merely studied ED utilisation.10 14 18

To understand the ED utilisation patterns of older adults, it is important to take their SES into account. Understanding the characteristics of older adult ED patients, including their SES, may be the first step to maintain or improve high quality of acute care. We hypothesise that low SES influences the risk of adverse health outcomes in the ED setting in a negative way and adds to the vulnerability of older adult ED patients even in a country in which healthcare access is organised for every inhabitant, regardless of SES.

The aim of this study was to determine differences between different SES groups among older adults, and additionally and most importantly, we investigated the association of SES with hospitalisation, inhospital mortality and ED revisits.

Method

Study design, setting and population

A retrospective cohort study was performed in the Maxima Medical Centre, a 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands. Yearly, approximately 30 000 patients visit the ED,19 of whom 30% are older adults (≥65 years). In the Netherlands, patients are usually referred to the ED by a GP. The GPs provide acute care all days of the week and every hour of the day, including out of office hours.

Older adults who visited the ED for all medical (including oncology) and surgical specialties in 1 year (between 1 September 2011 and 31 August 2012) were included. Data from the acute cardiac care unit and gynaecology unit were not available in the database, because these patients do not visit the ED.

Data of the ED visits were automatically extracted from the electronic patient records (Chipsoft-EZIS, V.5.2). Categorisation of the data was done according to a fixed data extraction form by one researcher (JJHW). A random sample of all variables was checked by another researcher (IvD). The patients’ zip code (on average 17 households per zip code) was used to determine the SES at a neighbourhood level by combining the median household income per month and mean value of the houses. Data on income were provided by Statistics Netherlands.20 This data set excluded zip codes with less than 10 households to guarantee anonymity. The median income data derived from zip codes in the database from Statistics Netherlands were linked to our database and subsequently divided into tertiles21: low (<€1800/month), intermediate (€1800–€2300/month) and high (>€2300/month). It was impossible to retrieve SES data for patients with unknown zip code or patients living abroad (Belgium), and therefore, these patients were excluded (n=511, 6.9%).

To investigate the effect of the living situation in the three SES groups, we conducted a subgroup analysis for the outcomes of community-dwelling patients and for patients who were institutionalised. Living situation was determined on the basis of zip codes, including those of the nursing and care home patients. The first ED visit in the study period was considered the index visit; other visits after the index visit were excluded to avoid duplicate analysis of the patients’ characteristics and outcomes.

Data collection and definitions

The following data were retrieved from the electronic patient record: age, gender, zip code, comorbidity, number of used medications. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to quantify comorbidity.22 All electronic patient (both ED and hospital) records were assessed to retrieve comorbidity. For a random sample of 50% of the patients per SES group, comorbidity was manually retrieved. It was not feasible to do this for all patients. The patients’ living situation was categorised into community-dwelling patients (living independently or with home care) and institutionalised patients (care home and nursing home).

To assess the severity of illness at presentation, the Manchester Triage System (MTS),23 vital parameters (systolic blood pressure, heart rate), laboratory tests (C reactive protein and leucocytes) and the ED diagnoses were retrieved. The triage level based on the five-level MTS was categorised into three groups: urgent (red and orange), moderate (yellow) and low (green). In our ED, the triage colour blue is not used because these patients almost never visit our ED. Classification of ED diagnoses was done according to the International Classification of Disease-10 (ICD-10).24 The group ‘other’ consisted out of the following diseases: nervous system, musculoskeletal and connective tissue, skin and subcutaneous tissue, eye and adnexa, ear and mastoid and psychiatric disorders.

Organisational factors retrieved were time of arrival, mode of referral (self-referral, GP, ambulance, specialist and other), specialty, number of diagnostic tests (sum of radiological tests, ECG, arterial blood gas analysis, laboratory tests, urinalysis, urine and blood culture), number of specialist consultations in the ED, ED length of stay (LOS) and hospital LOS. Time of presentation was classified into three shifts: day (08:00–18:00), evening (18:00–12:00) and night (12:00–08:00). The following specialties were considered surgical: (general) surgery, plastic surgery, urology and orthopaedics. Pulmonology, neurology, internal medicine and gastroenterology were considered medical specialties. Hospital LOS was defined as the number of days between hospital admission and hospital discharge. Dates of death during hospital stay and of the ED return visit were retrieved. The data were extracted by one trained medical abstractor who was blinded for the study hypothesis.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.22.0. Comparisons between two SES groups (low vs intermediate, low vs high and intermediate vs high) were conducted using analysis of variance (post hoc Tukey’s test) for continuous data and the χ2 test for categorical data. For continuous variables that were not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used. Missing data were categorised as ‘unknown’ and included in the analyses of categorical parameters to explore the influence of missing values. To investigate the independent effect of SES on hospitalisation, inhospital mortality and 30-day ED return visits, logistic regression analyses were performed. Multivariable analysis was performed to calculate the adjusted OR and in order to estimate the effect of confounders of age, gender, triage level and CCI. Age, CCI and medications were included as a linear variable in this analysis. For day of the week, a weekday was reference, and for sex, female was reference. Triage level was categorised as follows: urgent, intermediate and low (reference). Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of ED revisits on mortality. For this analysis, those who died during hospitalisation were excluded (n=199). To estimate the effect of the living situation on the SES and their outcomes, patients were divided into community-dwelling patients and institutionalised patients. OR and corresponding 95% CI were calculated for each of the outcomes. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

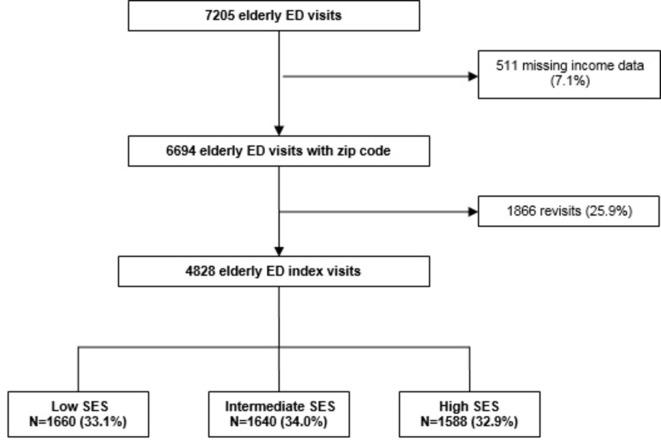

During the study period, 7205 ED visits by older adult patients were registered in our ED. In total, 511 patients (7.1%) were excluded because income data were missing and 1866 visits (25.9%) because the visit was a revisit. In total, 4828 index visits were included. Of these, 1660 visits (33.1%) were classified as having a low SES, 1640 (34.0%) as intermediate and 1588 (32.9%) as having a high SES (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of older adult patients divided into three SES groups. ED, emergency department; SES, socioeconomic status.

Patient characteristics

The mean age of the study population was 77±7.7 years, and slightly less patients were men (44.5%) (table 1). In total, 4381 (90.7%) were community-dwelling patients and 9.2% lived institutionalised. Patients were mostly referred by a GP (58.5%) and were triaged as having moderate urgency (43.8%). More than half (56.5%) of the patients were hospitalised, and their median hospital LOS was 5 days. Inhospital mortality was 4.1%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and SES of older adult patients visiting the ED

| Characteristics | Total population n=4828 |

Socioeconomic status | P value | ||

| Low n=1660 (33.1%) |

Intermediate n=1640 (34.0%) |

High n=1588 (32.9%) |

|||

| Age, years | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 77 (7.7) | 80 (7.6) | 76 (7.6) | 75 (7.4) | <0.001† |

| Median (IQR)* | 77 (12) | 80 (11) | 76 (12) | 74 (12) | |

| Gender, n (%)* | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 2149 (44.5) | 618 (38.6) | 759 (46.3) | 772 (48.6) | |

| Female | 2679 (55.5) | 982 (61.4) | 881 (53.7) | 816 (51.4) | |

| CCI, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.0 (0–8) | 1.0 (0–10) | 1.0 (0–11) | 0.09 |

| Unknown, n (%) | 45 (5.3) | 49 (5.3) | 54 (6.2) | ||

| No of medications, mean (SD)* | 2.5 (4.3) | 3.3 (4.7) | 2.4 (4.2) | 1.9 (3.9) | <0.001‡ |

| Mode of referral*, n (%) | |||||

| General practitioner | 2680 (55.5) | 937 (61.8) | 905 (57.8) | 838 (56.0) | 0.03 |

| Self-referral | 852 (17.6) | 215 (13.4) | 292 (17.8) | 345 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Ambulance | 664 (13.8) | 244 (15.3) | 237 (14.5) | 183 (11.5) | 0.01 |

| Specialist | 632 (13.1) | 204 (9.6) | 206 (9.9) | 222 (10.8) | 0.75 |

| Living situation*, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Community-dwelling | 4381 (90.7) | 1266 (79.1) | 1556 (94.9) | 1559 (98.2) | |

| Institutionalised | 443 (9.2) | 330 (20.6) | 84 (5.1) | 29 (1.8) | |

| Missing | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 0 | 0 | |

P values low, intermediate and high SES: using the χ2 test, analysis of variance (post hoc Tukey’s test) and Mann-Whitney U test.

*P<0.05.

†P value low vs intermediate <0.001, low vs high <0.001, intermediate vs high 0.001.

‡P value low vs intermediate 0.001, low vs high <0.001, intermediate vs high 0.042.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ED, emergency department; SES, socioeconomic status.

Patient characteristics and socioeconomic status

Patients with a low or intermediate SES were older than patients with a high SES (80 vs 76 and 75 years, respectively, P<0.001) (table 1). Male patients less frequently had a low SES than intermediate and high SES patients (38.6% vs 46.3% and 48.6%, respectively, P<0.001). The GP had referred patients in the low SES group more often than in the intermediate and high SES group (61.8% vs 57.8% and 56.0%, respectively, P=0.03). Patients in the low SES group used more medications than the high SES group (3.3 vs 1.9, P<0.001).

Organisational and clinical parameters in the ED and SES

There were no differences in the specialties (surgical vs medical) that treated the patients nor in time of presentation between the three SES groups (table 2). In addition, the vital parameters at presentation were comparable between the three groups. Patients with a low SES more often had a higher urgent triage level than the high SES group; however, this difference was not significant (15.4% vs 12.1%, P=0.02). In the low and the intermediate SES group, more diagnostics tests were performed than in the high SES group (mean 2.3 vs 2.1 vs 2.0, respectively, P<0.001). Patients with low SES had a longer ED LOS than patients with intermediate and high SES (140 min vs 133 vs 133, respectively, P=0.01). Diagnoses differed between the three groups: endocrine diseases were more common in the low SES group (3.1%) than in the intermediate or high SES group (1.7% and 1.6%, P=0.03), and the same was observed for infectious diseases (table 2).

Table 2.

Organisational and clinical parameters of older adult ED patients within the different SES groups

| Socioeconomic status | P value | |||

| Low n=1660 (33.1%) |

Intermediate n=1640 (34.0%) |

High n=1588 (32.9%) |

||

| Specialism, n (%) | 0.16 | |||

| Medical | 879 (54.9) | 858 (52.3) | 822 (51.8) | |

| Surgical | 721 (45.1) | 782 (47.7) | 766 (48.2) | |

| Shift, n (%) | 0.15 | |||

| Morning | 1130 (70.9) | 1148 (70.2) | 1169 (73.7) | |

| Evening | 240 (21.3) | 354 (21.7) | 318 (20.0) | |

| Night | 124 (7.8) | 133 (8.1) | 100 (6.3) | |

| Level of triage, n (%) | ||||

| Low* | 628 (39.8) | 640 (39.7) | 687 (44.0) | 0.02 |

| Moderate | 702 (44.5) | 730 (35.3) | 683 (43.7) | 0.69 |

| Urgent | 246 (15.4) | 242 (14.8) | 192 (12.1) | 0.02 |

| No triage | 24 (1.5) | 28 (1.7) | 26 (1.6) | 0.98 |

| Extra consultations at ED, n (%) | 0.80 | |||

| None | 1376 (86.0) | 1407 (85.6) | 1365 (86.0) | |

| 1 | 200 (12.5) | 215 (13.1) | 199 (12.5) | |

| ≥2 | 24 (0.5) | 18 (1.1) | 24 (1.4) | |

| Vital parameters | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 152 (31.7) | 153 (31.3) | 152 (30.8) | 0.94 |

| Missing, n (%) | 428 (26.9) | 530 (32.4) | 545 (35.5) | |

| Heart rate (min), mean (SD) | 81.5 (17.0) | 82.5 (18.1) | 82.1 (17.7) | 0.32 |

| Missing, n (%) | 734 (45.9) | 806 (49.1) | 819 (51.6) | |

| Medical procedures at ED | ||||

| No of diagnostic tests, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.7) | <0.001† |

| Laboratory test, n (%)* | 1081 (67.9) | 1046 (64.1) | 974 (61.7) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 16 (60) | 14 (55) | 15 (66) | 0.47 |

| Leucocytes (x109/L), median (IQR) | 9.2 (6) | 9.3 (5) | 8.8 (5) | 0.91 |

| Diagnosis at ED, n (%) | ||||

| Injury | 487 (30.6) | 504 (30.8) | 508 (32.2) | 0.56 |

| Otherwise | 280 (17.6) | 286 (17.5) | 289 (18.3) | 0.79 |

| Circulatory/Respiratory | 232 (14.6) | 257 (15.7) | 201 (12.7) | 0.06 |

| Other | 202 (12.7) | 217 (13.3) | 218 (18.3) | 0.64 |

| Digestive | 163 (10.2) | 175 (10.8) | 169 (10.7) | 0.88 |

| Genitourinary | 68 (4.3) | 73 (4.5) | 58 (3.7) | 0.51 |

| Infectious | 65 (4.1) | 52 (3.2) | 45 (2.8) | 0.14 |

| Endocrine/Metabolic | 50 (3.1) | 28 (1.7) | 25 (1.6) | 0.03 |

| Neoplasm/haematology | 47 (2.9) | 52 (3.2) | 70 (4.4) | 0.05 |

| Missing | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 9 (0.6) | |

| ED LOS in minutes, median (IQR)* | 140 (83) | 133 (90) | 133 (87) | 0.01‡ |

ED diagnosis ‘other’ (ICD-10 classification)=diseases of the nervous system, musculoskeletal and connective tissue, skin and subcutaneous tissue, eye and adnexa, ear and mastoid and mental. P values low, intermediate and high SES: using the χ2 test, analysis of variance (post hoc Tukey’s test) and Mann-Whitney U test.

*P<0.05.

†P value low vs intermediate <0.001, low vs high <0.001, intermediate vs high <0.01.

‡P value low vs intermediate 0.01, low vs high 0.004, intermediate vs high 0.93.

CRP, C reactive protein; ED, emergency department; LOS, length of stay; SES, socioeconomic status.

Patient outcomes and SES

Patients with a low SES were more frequently hospitalised than the intermediate and high SES group (62.3% vs 55.4% vs 52.3%, respectively, P<0.001, table 3). In addition, patients with a low SES had a longer hospital LOS than patients with a high SES (6.0 vs 5.0 days, P<0.001). However, the hospital LOS did not differ between intermediate SES and high SES patients (5 days in both groups, P=0.45). The finding that low SES patients were more often hospitalised than the high SES group turned out not to be independent of age and comorbidity (adjusted OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.4, table 3). When stratified according to living situation, low SES community-dwelling patients had a higher risk of hospitalisation with an OR of 1.3 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.7) compared with patients with a high SES. In contrast, institutionalised low SES patients had a lower risk of hospitalisation with an OR of 0.2 (95% CI:0.1 to 0.7). Intermediate SES patients did not have a higher odd for hospitalisation (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.4) than high SES patients.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of the effect on SES on ED outcomes and within different living situations

| Socioeconomic status | Number (%) | All patients n=4828 (OR 95% CI) |

Community-dwelling patients n=4381 (OR 95% CI) |

Institutionalised patients n=443 (OR 95% CI) |

|

| Hospitalisation* | Low | 996/1660 (62.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.7) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.7) |

| Intermediate | 909/1640 (55.4) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.1 (0.95 to 1.4) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.2) | |

| High | 830/1588 (52.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Inhospital mortality† | Low | 86/996 (5.4) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.6) | 0.8 (0.1 to 6.8) |

| Intermediate | 58/909 (3.5) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) | 0.4 (0.1 to 4.0) | |

| High | 55/830 (3.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 30 day ED revisitsठ| Low | 184/1514 (11.5) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.2 to 4.7) |

| Intermediate | 220/1582 (13.5) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.2 to 4.6) | |

| High | 196/1533 (12.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

*Adjusted variable include age and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

†Adjusted for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index and triage level.

‡Adjusted for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index and gender,

§without patients who died during hospitalisation.

ED, emergency department; SES, socioeconomic status.

Inhospital mortality was higher for the low SES group (5.4%) compared with the intermediate (3.5%) and the high SES group (3.5%, P=0.01, unadjusted ORlow vs high: 0.6 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9). The difference in inhospital mortality between low and high SES patients was no longer significant when adjusted for age, comorbidity and triage level (adjusted OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.7 to 2.0).

There was no difference in 30-day ED revisit rate between the low, intermediate and high SES group (21.3%, 20.4% vs 20.8%, respectively, P=0.88). Neither was the 30-day ED revisit rate different after correcting for age, comorbidity and gender (adjusted OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.4). Moreover, adjusting for the living situation did not alter the results significantly (table 3).

Discussion

Our study was a large population-based study that investigated the association of SES with ED visits of older adult (≥65 years) patients. We found that older adult community-dwelling ED patients with a low SES have a higher risk of hospitalisation than patients with a high SES. Moreover, low SES patients had more often a higher triage level, had more diagnostics test and longer ED LOS compared with other SES groups. However, inhospital mortality and the number of ED return visits were not different between the three SES groups.

We hypothesised that patients with low SES would be less healthy than those with a higher SES, which indirectly would result in higher admission rates and inhospital mortality after presentation at the ED. Our data allowed us to determine important confounders, such as comorbidity, organisational factors and the severity of illness at the ED, which makes it possible to contribute important information to already existing evidence on the topic of SES, where some studies did not adjust for potential and important confounders.7 25 Our study indeed observed a higher chance of hospitalisation (OR 1.3, CI 1.1 to 1.7) for community-dwelling patients with a low SES than for patients with intermediate/high SES. This finding is in line with other studies.9 26 27 It may be possible that part of the community-dwelling frail patients were admitted for care problems, which is not a reason for admission for institutionalised patients as extra care is available for these patients. Future studies should elaborate the living arrangements and social network of older adults to investigate the influence of these matters on ED usage.

Inhospital mortality and ED revisits within 30 days were not associated with SES. This contrasts with other studies that found a higher risk of inhospital mortality and readmissions in older adult patients with a low SES,8 16 17 but is in line with other studies that did not find an association.11 12 18 The association of low SES and adverse outcomes was found in studies that included patients with a specific diagnosis (eg, pneumonia or heart failure)18 28 or that analysed the number of ED visits per SES category,4 6 9 29 whereas our study focused on an undifferentiated, and therefore, more generalisable, older adult ED population. Another reason for not finding an association between low SES and outcomes might be that most studies did not account for differences in living situation.17 30 31 We found that care and nursing homes were mostly situated in low SES areas, while their inhabitants will probably belong to all three SES.32 Additionally, institutionalised patients may influence revisit rates because they are treated by their own doctor in the nursing home. It may be useful to take the living situation into account when using SES based on zip code because care facilities structures at home influence ED outcomes.

The fact that we did not find an association between SES and inhospital mortality and revisits may be due to the organisation of the healthcare system in the Netherlands and may underscore/reflect that our healthcare is indeed accessible to all patients, regardless of their SES. In the Netherlands, the healthcare system consists of a well-organised GP network, with 24 hours a day access for acute care patients, which is equally accessible for every inhabitant.29 In the Netherlands, care provided by the GP is fully covered by the basic obligatory health insurance.33 Therefore, this system provides equal access to healthcare by the GP to every resident, independent of their SES.5 34–36 In addition, this care selects the most severely ill patients for referral to the ED. The acute healthcare system differs over the countries, and in some countries, for instance the USA, the ED is used as a safety net for underserved and uninsured patients.37 Also, equally important, the financial healthcare structure is different worldwide. In short, specifically regarding acute care, differences in organisation and financial coverage of acute care make comparisons between countries difficult.38

In the Netherlands, older adults are, in general, financially well covered,39 as only 3.5% of them are poor.39 Concerning other studies on older adults and SES, the methods of determining SES differed substantially, and some included education, income and occupancy, but none of the methods have proved to be comprehensive enough.40 One study in Canada among older adults that determined factors of ED usage matched postal codes with several indicators, such as income, employment and living alone.10 In a Mediterranean study, SES was defined based on years of education and the mean annual income of the family.41 In conclusion, the comparison of studies on SES is complicated by different levels of SES in the general population and by the way SES is defined.

Apart from the above mentioned, the following study limitations should be mentioned. First, our results are not generalisable to cardiology and gynaecology patients as we excluded these patients. For these cardiology patients, it is known that low SES may have a stronger association with adverse outcomes,42 and excluding these from our study may explain that we did not find associations between SES and outcome (except for hospitalisation in community dwelling patients). Second, we retrieved SES on the basis of zip codes, which may be imprecise and yield smaller associations of SES with adverse outcomes.43 However, one zip code in the database of Statistics Netherlands covers only 17 households and, therefore, we consider this way of retrieving SES rather reliable.44 45 Thirdly, retrieving SES of patients living in a nursing home or other care home facilities on the basis of zip code is probably not reliable. Therefore, we made subgroup analysis of community-dwelling patients and institutionalised patients, which is a strong point of our study. Lastly, coding for the living situation may not be precise, but we think that this does not lead to an underestimation since the percentage of institutionalised patients (9.1%) is almost similar to percentages given in another study (9.0%).46

In this study, we provided important information in terms of health outcomes on the SES in the acute healthcare setting in the vulnerable older adult population. We investigated a large unselected group of older adult ED patients stratified to living situation, which provides additional knowledge on the care and problems of older adult patients in the ED. Our study shows that in a country with assumed equal healthcare access, only minor outcome differences were observed between different SES groups. Therefore, physicians should be aware of the potential differences between SES groups given the higher chance of hospitalisation. Improvement in adequately diagnosing and treating older adult patients is important, but the additional value of SES in the emergency care should be evaluated further to develop effective interventions to ensure high quality of care. Future studies should elaborate the living arrangements and social network of older adults because these probably influence access to the ED and the number of (re-)admissions.

In conclusion, low SES community-dwelling older adults were more often hospitalised than high SES community-dwelling patients, but there were no differences in inhospital mortality and ED revisits between the SES groups.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

ID and PMS contributed equally.

Contributors: JJHW and SHAB conceived the study and designed the protocol. SLEL contributed to the design for the overall older adults project. JJHW, PMS and IvD analysed and interpreted the data. HRH supervised the conduct of the study and data collection. JJHW, PMS and IvD drafted the manuscript. MJA helped with the statistical analyses. JJHW designed the database. JJHW, IvD, PMS, SHAB, MJA, SLEL and HRH contributed substantially to its revision and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of Máxima Medical Centre approved this study and confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO) was not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data of the study are available from the Data Governance Board of Maxima Medical Centre Instituional Data Access/Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Data are from the socioeconomic status study when contacting the data governance board (Jolanda.Luime@mmc.nl).

References

- 1.Hoogendijk EO, van Hout HP, Heymans MW, et al. . Explaining the association between educational level and frailty in older adults: results from a 13-year longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Ann Epidemiol 2014;24:538–44. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowthian JA, Curtis AJ, Cameron PA, et al. . Systematic review of trends in emergency department attendances: an Australian perspective. Emerg Med J 2011;28:373–7. 10.1136/emj.2010.099226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. . Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2468–81. 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Droomers M, Westert GP. Do lower socioeconomic groups use more health services, because they suffer from more illnesses? Eur J Public Health 2004;14:311–3. 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, van der Burg H, et al. . Equity in the delivery of health care in Europe and the US. J Health Econ 2000;19:553–83. 10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan Y, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, et al. . A population-based study of the association between socioeconomic status and emergency department utilization in Ontario, Canada. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:836–43. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tozer AP, Belanger P, Moore K, et al. . Socioeconomic status of emergency department users in Ontario, 2003 to 2009. CJEM 2014;16:220–5. 10.2310/8000.2013.131048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begley C, Basu R, Lairson D, et al. . Socioeconomic status, health care use, and outcomes: persistence of disparities over time. Epilepsia 2011;52:957–64. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filc D, Davidovich N, Novack L, et al. . Is socioeconomic status associated with utilization of health care services in a single-payer universal health care system? Int J Equity Health 2014;13:115 10.1186/s12939-014-0115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ionescu-Ittu R, McCusker J, Ciampi A, et al. . Continuity of primary care and emergency department utilization among elderly people. CMAJ 2007;177:1362–8. 10.1503/cmaj.061615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho KM, Dobb GJ, Knuiman M, et al. . The effect of socioeconomic status on outcomes for seriously ill patients: a linked data cohort study. Med J Aust 2008;189:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alter DA, Chong A, Austin PC, et al. . Socioeconomic status and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:82–93. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, et al. . Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:261–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos M. Impact of socioeconomic status on Brazilian elderly health. Rev Saude Publica 2007;41:616–24. 10.1590/S0034-89102006005000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cournane S, Conway R, Byrne D, et al. . Social deprivation and the rate of emergency medical admission for older persons. QJM 2016;109:645–51. 10.1093/qjmed/hcw029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchings A, Raine R, Brady A, et al. . Socioeconomic status and outcome from intensive care in England and Wales. Med Care 2004;42:943–51. 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rathore SS, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, et al. . Socioeconomic status, treatment, and outcomes among elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the National heart failure project. Am Heart J 2006;152:371–8. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izquierdo C, Oviedo M, Ruiz L, et al. . Influence of socioeconomic status on community-acquired pneumonia outcomes in elderly patients requiring hospitalization: a multicenter observational study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:421 10.1186/1471-2458-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouns SH, Dortmans MK, Jonkers FS, et al. . Hyponatraemia in elderly emergency department patients: a marker of frailty. Neth J Med 2014;72:311–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centraal bureau voor de statistiek. Inhoud kerncijfers postcodegebieden 2008-2012, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunst AE, Bos V, Mackenback JP. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in health in the european union: guidelines and illustrations. EU working group on socio-economic inequalities in health. 2011.

- 22.Needham DM, Scales DC, Laupacis A, et al. . A systematic review of the charlson comorbidity index using canadian administrative databases: a perspective on risk adjustment in critical care research. J Crit Care 2005;20:12–19. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachariasse JM, Seiger N, Rood PP, et al. . Validity of the manchester triage system in emergency care: a prospective observational study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170811 10.1371/journal.pone.0170811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. . Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagher A, Andersson L, Wingren CJ, et al. . Socio-economic status and major trauma in a scandinavian urban city: a population-based case-control study. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:217–23. 10.1177/1403494815616302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stern RS, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The emergency department as a pathway to admission for poor and high-cost patients. JAMA 1991;266:2238–43. 10.1001/jama.1991.03470160070034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonelli-Incalzi R, Ancona C, Forastiere F, et al. . Socioeconomic status and hospitalization in the very old: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2007;7:227 10.1186/1471-2458-7-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhayana R, Vermeulen MJ, Li Q, et al. . Socioeconomic status and the use of computed tomography in the emergency department. CJEM 2014;16:288–95. 10.2310/8000.2013.131102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Meer JBW, van den Bos J, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic differences in the utilization of health services in a Dutch population: the contribution of health status. Health Policy 1996;37:1–18. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)87673-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cressman AM, Macdonald EM, Yao Z, et al. . Socioeconomic status and risk of hemorrhage during warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation: a population-based study. Am Heart J 2015;170:133–40. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Govindarajan P, Gonzales R, Maselli JH, et al. . Regional differences in emergency medical services use for patients with acute stroke (findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Emergency Department Data File). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:e257–63. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arendts G, Howard K. The interface between residential aged care and the emergency department: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2010;39:306–12. 10.1093/ageing/afq008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Linden MC, Lindeboom R, de Haan R, et al. . Unscheduled return visits to a Dutch inner-city emergency department. Int J Emerg Med 2014;7:23 10.1186/s12245-014-0023-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. . International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Linden MC, Lindeboom R, van der Linden N, et al. . Self-referring patients at the emergency department: appropriateness of ED use and motives for self-referral. Int J Emerg Med 2014;7:28 10.1186/s12245-014-0028-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes JL. Emergency medicine in the Netherlands. Emerg Med Australas 2010;22:75–81. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Somma S, Paladino L, Vaughan L, et al. . Overcrowding in emergency department: an international issue. Intern Emerg Med 2015;10:171–5. 10.1007/s11739-014-1154-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grundy E, Holt G. The socioeconomic status of older adults: how should we measure it in studies of health inequalities? J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:895–904. 10.1136/jech.55.12.895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smits CH, van den Beld HK, Aartsen MJ, et al. . Aging in the Netherlands: state of the art and science. Gerontologist 2014;54:335–43. 10.1093/geront/gnt096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martelin T. Mortality by indicators of socioeconomic status among the finnish elderly. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1257–78. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90190-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katsarou A, Tyrovolas S, Psaltopoulou T, et al. . Socio-economic status, place of residence and dietary habits among the elderly: the Mediterranean islands study. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:1614–21. 10.1017/S1368980010000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlsson AC, Li X, Holzmann MJ, et al. . Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease in individuals between 40 and 50 years. Heart 2016;102:775–82. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aarts MJ, van der Aa MA, Coebergh JW, et al. . Reduction of socioeconomic inequality in cancer incidence in the South of the Netherlands during 1996-2008. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2633–46. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bos V, Kunst AE, Mackenback J. verslag aan de programmacommissie sociaal-economische gezondheidsverschillen II [In Dutch]. Rotterdam: Instituut Maatschappelijke Gezondheidszorg, Erasmus Universiteit, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smits J, Keij I, Mackenbach JP. Sociaal-economische gezondheidsverschillen: van verklaren naar verkleinen [In Dutch]. Den Haag: Zon/MW, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ribbe MW, Ljunggren G, Steel K, et al. . Nursing homes in 10 nations: a comparison between countries and settings. Age Ageing 1997;26(Suppl 2):3–12. 10.1093/ageing/26.suppl_2.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.