Abstract

Objectives

Responding to the serious shortage of physicians in rural areas, the Japanese government has aggressively increased the number of entrants to medical schools since 2008, mostly as a chiikiwaku, entrants filling a regional quota. The quota has spread to most medical schools, and these entrants occupied 16% of all medical school seats in 2016. Most of these entrants were admitted to medical school with a scholarship with the understanding that after graduation they will practise in designated areas of their home prefectures for several years. The quota and scholarship programmes will be revised by the government starting in 2018. This study evaluates the intermediate outcomes of these programmes.

Design

Cross-sectional survey to all prefectural governments and medical schools every year from 2014 to 2017 to obtain data on medical graduates.

Settings

Nationwide.

Participants

All quota and non-quota graduates with prefecture scholarship in each prefecture, and all the quota graduates without scholarship in each medical school.

Primary outcome measures

Passing rate of the National License Examination for Physicians and the percentage of graduates who have not bought out the scholarship contract after graduation.

Results

Most prefectures and medical schools in Japan participated in this study (97.8%–100%). Quota graduates with scholarship were significantly more likely to pass the National License Examination for Physicians than the other medical graduates in Japan at all the years (97.9%, 96.7%, 97.4% and 94.7% vs 93.9%, 94.5%, 94.3% and 91.8%, respectively). The percentage of quota graduates with scholarship who remained in the scholarship contract 3 years after graduation was 92.2% and 89.9% for non-quota graduates with scholarship.

Conclusions

Quota entrants showed better academic performance than their peers. Most of the quota graduates remained in the contractual workforce. The imminent revision of the national policy regarding quota and scholarship programmes needs to be based on this evidence.

Keywords: physician, geography, health policy, japan

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study shows intermediate outcomes of quota admission programmes of medical schools and prefecture scholarship programmes, one of the largest national policies enacted to improve Japan’s geographic maldistribution of physicians.

With support from concerned ministries and the representative body of medical schools, almost all of Japan’s prefectural governments and medical schools participated in this study, which enabled the collection of reliable information on study subjects every year.

The passing rates of the National License Examination for Physicians of the quota graduates with scholarship, quota graduates without scholarship and non-quota graduates with scholarship were compared with that of the other medical graduates in Japan.

The percentages of quota and non-quota graduates with scholarship who have not bought out the scholarship contract were calculated and compared with each other.

The geographic location of the quota graduates and scholarship recipients are not shown in this study, which will be assessed in the ongoing cohort study of which this study is a part.

Introduction

Geographic distribution of physicians in Japan

The geographic inequity of physician distribution has long been a social problem in Japan and in many other countries. Japan’s national and local governments have attempted to solve this problem by establishing public hospitals and clinics in rural areas since 1950s, creating at least one medical school in each prefecture in 1960s and 1970s, including Jichi Medical University in 1972, which is exclusively responsible for producing rural physicians.1 2

Over the long term, these policies have increased the number of physicians in rural areas,3 but many studies revealed that the disparity in proportional representation of urban and rural physicians has persisted.3–8 This maldistribution of physicians has worsened since 2004 when the new residency training programme for the physicians within the first 2 years after graduation was introduced nationwide.4 8 Furthermore, additional specialty training for physicians after residency training, scheduled to start in 2018, has caused concern among healthcare professionals and policy makers that young physicians will be even more likely to cluster in large cities.9–12

Chiikiwaku (regional quota) and prefecture scholarship as a national policy

In response to such a situation, the national government has aggressively increased the number of entrants to medical schools since 2008. Most of these entrants were admitted as a chiikiwaku, a regional quota of a medical school. The model of these quotas was Jichi Medical University. The quota had spread to 67 of the 80 medical schools by the end of 2016.13 The quota is a special admission quota of a medical school in which entrants were admitted under the condition that they practise in designated areas of their home prefectures, usually in rural areas in exchange for a scholarship by the prefectural government.14 The scholarship is given for the all 6 years of undergraduate medical education, and the graduate is required to work in the prefecture for 9 years after graduation including 4 years in rural areas of the prefecture. The prefecture governments allocate a budget for the scholarship according to the national policy. Some medical schools have a regional quota without the scholarship. Entrants under this form of quota thus are not contractually required to work in designated areas though they are expected to do so.15 The number of entrants to any form of regional quota is now 1504, accounting for 16% of all medical school students in Japan.16 17

Apart from the scholarship coupled with the quota admission, there are scholarship programmes of prefectural governments for non-chiikiwaku students. These scholarships are also based in the national policy. The scholarship is given to a medical student who has been admitted to a medical school through a conventional admission process and then applies to the scholarship programme. The recipients of these scholarships are also required to work in the designated areas of the prefecture for a certain amount of time, usually 1.5 times the length of the term of the scholarship. Half of that contractual period is to be spent practising in rural areas of the prefecture.15

Academic performance and compliance of scholarship contract

Admission to medical schools in Japan has been highly competitive. In 2016, one in four applicants of public medical schools and one in 16 applicants of private medical schools were accepted.18 19 Medical schools have not traditionally imposed restrictions on the geographic background of applicants, so each medical school, even rural ones, attracts applicants from all over Japan. Most of the medical schools require a few days of written tests coupled with a short interview of all the applicants, so given the lack of time for interviews, admission decisions are largely based on scores of written test.

Entrance examination for regional quota is different. Most medical schools admit students only from the prefecture in which the students live and/or from which the scholarship is given. In addition, many medical schools consider only applicants who have been recommended by their high schools. Thus, there are far fewer applicants to the quotas. The application process for quota applicants is usually a combination of written test, academic records in the high school, a personal statement and an interview. The academic test thus carries less weight as compared with the conventional admission process. Because of these differences, the general population and medical educators are concerned about the academic performance of quota entrants. In addition, there is a concern that many quota entrants may buy out their contract to avoid practising in the prefecture and/or in rural areas.15 However, so far, no researchers seem to have compared the academic and contractual outcomes of quota and non-quota students in Japan.

Objectives of this study

In this study, we compared the results of the National License Examination for Physicians among graduates of quota with scholarship, quota without scholarship, non-quota with scholarship and all the other new medical graduates in Japan. We also examined the percentages of those graduates who have not bought out the scholarship. We assessed the intermediate outcomes of quota and scholarship programmes, so that the results can be used to inform political decision makers for future revision of the quota and scholarship programmes.

Methods

Design and settings

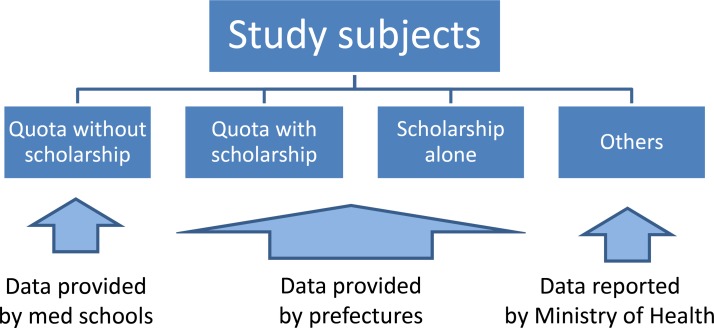

This study is a part of the nationwide cohort study conducted by the Japanese Council for Community-based Medical Education (JCCME).15 Yearly cross-sectional outcomes of the cohort study are reported in this study. The study period is from 2014 to 2017. The study includes three groups of subjects: quota graduates with scholarship, non-quota graduates with scholarship (scholarship alone) and quota graduates without scholarship (quota alone). Data on the former two groups were collected from prefectures and that on the last group were collected from medical schools (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study subjects and data collection. ‘Quota with scholarship’ are students who entered a regional quota and received a prefecture scholarship, ‘quota alone’ are students who entered the quota but did not receive the scholarship, ‘scholarship alone’ are students who received the scholarship but did not enter the quota and others are all medical students excluding quota and scholarship ones.

Every November, the cohort study office of JCCME sent a presurvey questionnaire to all the 47 prefectures and all the 77 medical schools except for Jichi Medical University, National Defence Medical College and University of Occupational and Environmental Health to ask which prefectures and medical schools have eligible subjects. Every year, all the prefectures and medical schools responded to this. In June of the survey year, the study office sends a survey questionnaire to each prefectural government to obtain information on the number of new graduates who had received scholarship, the number who passed the National License Examination for Physicians and the number who have bought out the scholarship. The cohort office sends a questionnaire to each medical school to obtain information on the number of quota students without scholarship and number who passed the National License Examination for Physicians. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Association of Japan Medical Colleges supported this study by requesting prefectures and/or medical schools to participate.

Definitions of quota and scholarship

In this study, a quota student is one whose ‘geographic background or location of graduated high schools of applicants are restricted and/or working place or specialty after graduation is clearly specified’. A scholarship is ‘given by a prefecture to a medical student which needs not to be paid back if the student works in designated areas by the prefecture for a certain period’.

Statistical analyses

Based on the data obtained from the prefectures and medical schools, passing rates of the National License Examination for Physicians were calculated for the subjects in quota with scholarship, quota without scholarship (quota alone) and non-quota with scholarship (scholarship alone). The rates in 2014 and 2015 have been reported previously,15 and in this study, results in 2016 and 2017 were added. These rates were compared with the passing rate of all the other medical graduates in Japan. The passing rate of the other graduates was calculated by subtracting the numbers of passed and failed subjects in quota with scholarship, quota alone and scholarship alone from those of all new graduates in Japan reported every year by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.20 21 The comparisons were conducted with the Fisher’s exact test for a part of 2014 analysis, because there were fewer than five failed subjects in quota with scholarship. All the other comparisons were conducted with the χ2 test of independence.

Also based on the data from the prefectures, retention rates for contractual workforce of subjects in quota with scholarship and subjects with scholarship alone were calculated. The retention rate is the percentage of graduates who are complying with the terms of being admitted to a quota and/or receiving scholarship. The retention rate of each group was calculated in each cohort of graduation year. The retention rate of all those who graduated between 2014 and 2017 was also calculated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis in which subjects with various observation periods were analysed. The retention rates were compared between the two groups with the log-rank test.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS V.24 (IBM-SPSS, Tokyo, Japan) and R V.3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P values less than 0.05 (two-sided test) were regarded as statistically significant.

All the data were provided and analysed anonymously.

Results

Response rates

Almost all prefectures and medical schools with eligible subjects participated in this study (response rates 97.8%–100%) (table 1). The response rate is the percentage of those who returned a completed questionnaire to the study office among all the prefectures or medical schools that have eligible subjects.

Table 1.

Response rates of prefectures and medical schools

| Year | Prefectures | Medical schools | |||||

| n* | Response rate (%) | Subjects | n* | Response rate (%) | Subjects | ||

| Quota with scholarship | Scholarship alone | Quota alone | |||||

| 2014 | 36/36 | 100 | 144 | 322 | 19/19 | 100 | 166 |

| 2015 | 45/46 | 97.8 | 305 | 391 | 22/22 | 100 | 253 |

| 2016 | 46/47 | 97.8 | 498 | 340 | 29/29 | 100 | 308 |

| 2017 | 47/47 | 100 | 609 | 376 | 31/31 | 100 | 382 |

*Both the number of eligible prefectures (medical schools) and that of responded prefectures (medical schools) are shown.

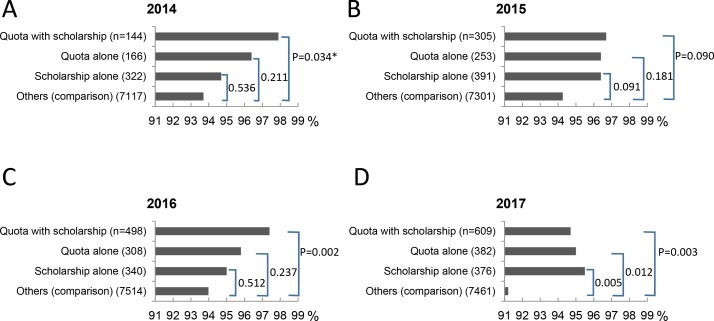

Passing rates of the National License Examination for Physicians

Throughout the study period, the passing rates of quota graduates with scholarship, quota graduates without scholarship and non-quota with scholarship were higher than the passing rate of all the other new medical graduates in Japan (figure 2A–D). The percentage of quota with scholarship was substantially higher than the percentage of all the other graduates in all the years (97.9%, 96.7%, 97.4% and 94.7% vs 93.9%, 94.5%, 94.3% and 91.8%, respectively), and the difference was statistically significant in all years except for 2015 (P=0.034, 0.090, 0.002 and 0.003, respectively). The passing rate of quota with scholarship was the highest among all the groups except for 2017 in which the percentage of scholarship alone was the highest.

Figure 2.

Passing rates of the National Licence Examination for Physicians: (A) 2014, (B) 2015, (C) 2016 and (D) 2017. Control data were from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.20 21 Rates in 2014 and 2015 have been reported previously.15 *Fisher’s exact test.

The passing rate of quota with scholarship was still higher than that of the comparison group except for 2017 even when the comparison group was limited to the graduates of public (ie, national or prefectural) medical schools (93.6%, 94.8%, 95.3% and 95.1%, respectively). The difference was however significant only in 2016 (P=0.16, 0.31, 0.02 and 0.31, respectively) (data not shown in the figure).

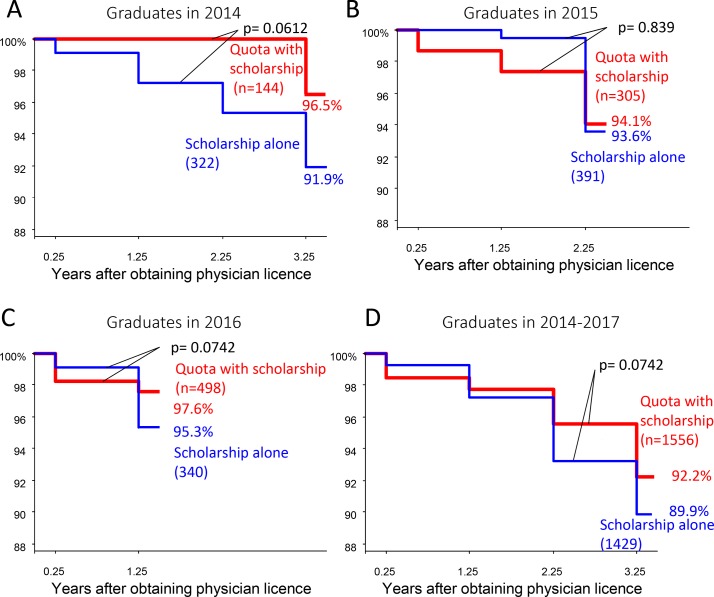

Retention rates for contractual work (non-buying-out rates)

Figure 3A–C shows the retention rates of subjects in quota with scholarship and those in non-quota with scholarship. Figure 3D shows the rates of all the graduates between 2014 and 2017. The retention rate varied by graduation year and at intervals after graduation. In all graduation years, the retention rate of quota with scholarship was higher than that of scholarship alone at the end of follow-up, but the difference was not statistically significant (figure 3A–C). The survival analysis including all the subjects who obtained physician licence between 2014 and 2017 showed that the retention rate 3.25 years after graduation was 92.2% for those in quota with scholarship and 89.9% for those with scholarship alone (statistically not significant: figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Retention rates of subjects in quota with scholarship and those in non-quota with scholarship (scholarship alone). (A) graduates in 2014, (B) 2015, (C) 2016 and (D) 2014–2017.

The 2014–2017 retention rate of quota with scholarship varied substantially among prefectures (78.4%–100%). The rate of scholarship alone likewise varied among prefectures (70.8%–100%) (data not shown in the figure).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the graduates of regional quota with scholarship were more likely to pass the National License Examination for Physicians than the other new graduates of medical schools. The percentage of those who remained in the contractual workforce accompanied with scholarship 3.25 years after graduation was 92.2% among those of quota with scholarship and 89.9% among those with scholarship alone.

There has been a concern about the academic level of quota entrants because they are admitted to medical school under different criteria.15 The results of this study, however, show that the concern is invalid at least for the observed period. In Japan, the length of undergraduate medical education is 6 years, which is long enough to obscure the correlation between academic performance at entrance and that at graduation.22 Also in the usual admission process, many applicants are examined over the course of a few days, which forces medical schools to choose entrants solely based on their test scores. Elements other than the written test score, such as the personal statement and interview result, are not as valued. In contrast, the admission process in many of the regional quotas is a combined evaluation of the applicant’s high school activities, a recommendation letter from the high school, an interview, an academic test and a personal statement. The variety of elements valued in the process may have contributed to a better academic performance of quota students, and subsequently the better outcome on the physician licence examination. The results of this study thus offer a warning to Japan’s conventional medical school admission process. The government of Japan is scheduled to revise, on a nationwide basis, the process of university entrance in 2021. This revision should make the selection of medical school applicants more effective.

There is a room for argument whether the contract retention rates shown in this study are high or low. The results shown are the overall value of all the subjects in all prefectures of Japan. In reality, however, there is a substantial difference among prefectures. It is thus necessary to evaluate the result in each prefecture or in each medical school. The retention rate of graduates from Jichi Medical University, founded in 1972 solely to produce rural physicians and became the model when making regional quota programmes all over the country, is 97%.23 The percentage is obviously higher than that of quota graduates shown in this study. However, the total amount of prefecture scholarship given to a Jichi student for 6 years is 23 million yen (equivalent to US$209 090), which is double the average amount of scholarship for a quota student: 12.2 million yen (US$110 909).13 24 In order to make the quota programme sustainable, we need to consider the balance between the financial burden of the country/prefecture and the certainty to secure physicians in needed areas. Also the differences in the training offered to students, in the focus of the school and in postgraduate training programmes may have contributed to the gap in retention rates between Jichi and quotas.

Internationally, there are many financial incentive programmes to recruit physicians to practise in rural areas.25 26 The estimated retention rate of the pooled subjects of these programmes was reported to be 71%.26 The retention rate of subjects in state scholarship programmes for medical students in the USA was 66.5%.27 While international data are favourable, it is not known if the relationships would hold for Japan. Thus, further study is needed in Japan.

This study has the following limitations. First, as this study gathered information about graduates, their academic performance and scholarship buy-out rate before graduation are unknown. According to the Association of Japan Medical Colleges, the straight graduation rate, which is the proportion of students who have finished their 6-year medical programme without repeating a school year, of quota students who entered in 2008 was 89.6% nationwide, which was higher than the rate of all the medical school entrants in the year (85.4%). The rate of quota entrants in 2009, which was 89.0%, was also higher than that of all medical students (84.2%).13 The report also mentioned that 0.7% of undergraduate quota students bought out their prefectural scholarship each year.13 This information should be added to the results of this study when assessing the effectiveness of quota and scholarship programmes. The geographic location of the quota graduates and scholarship recipients are not shown in this study. Their location, particularly after their contractual periods, is the most important outcome of these programmes and will be assessed in the near future, based on the data from the ongoing cohort study.

Regional quotas and prefecture scholarships are based on temporary legislation by the national government, and thus the programmes will be revised starting in 2018. In most of the prefectures, however, the first generation of the quota entrants is still undergoing its clinical training or have just started their practice in rural areas. So, as of this writing (summer 2017), we cannot assess the final outcomes of these programmes. All we can do is to collect intermediate outcomes like those shown in this study, analyse them in a variety of dimensions and engage in evidence-based decision making for the future national policies while accumulating data for the next assessment.

Conclusion

The passing rate of the entrants to the chiikiwaku, regional quota of entrants to medical schools, for the National License Examination for Physicians was higher than the rate of non-quota medical graduates. The passing rate of prefecture scholarship recipients was also higher than non-recipients. More than 90% of quota physicians with scholarship were complying with the terms of their contract for more than 3 years after obtaining the physician licence during which we observed. The imminent revision of the national policy regarding the quota and scholarship programmes should be based on these intermediate outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MM contributed to the study design, tools, study administration, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data and writing the draft. KT and TM contributed to the study design, tools, study administration, data interpretation and writing the draft. ST and KI contributed to the study design, interpretation of data and writing the draft. SK contributed to the analysis and writing the draft. TO and SI contributed to the study administration and data collection.

Funding: This study is funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), Grant Number (25460803).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee for epidemiological research of Hiroshima University (ref. no. 778) and the Research Ethics Committee of Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (ref. no. 13091342).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Conditions of the ethical approvals permit the cohort office (Department of Community-Based Medical System, Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University) and the suboffice (Department of Community Medicine, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Science) to share the aggregated data with stakeholders or researchers.

References

- 1. Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E, et al. . Retention of physicians in rural Japan: concerted efforts of the government, prefectures, municipalities and medical schools. Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsumoto M, Takeuchi K, Yokobayashi K, et al. . Geographic maldistribution of physicians in Japan: increasing the number of generalists is one solution. J Gen Fam Med 2015;16:260–4. 10.14442/jgfm.16.4_260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inoue K, Matsumoto M, Toyokawa S, et al. . Transition of physician distribution (1980–2002) in Japan and factors predicting future rural practice. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toyabe S. Trend in geographic distribution of physicians in Japan. Int J Equity Health 2009;8:5 10.1186/1475-9276-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanihara S, Kobayashi Y, Une H, et al. . Urbanization and physician maldistribution: a longitudinal study in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:260 10.1186/1472-6963-11-260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kobayashi Y, Takaki H. Geographic distribution of physicians in Japan. Lancet 1992;340:1391–3. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92569-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Bowman R, et al. . Geographical distributions of physicians in Japan and US: impact of healthcare system on physician dispersal pattern. Health Policy 2010;96:255–61. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hara K, Otsubo T, Kunisawa S, et al. . Examining sufficiency and equity in the geographic distribution of physicians in Japan: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013922 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iwata K, Mosby DJ, Sakane M. Board certification in Japan: corruption and near-collapse of reform. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:436 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-134994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Japan Association of City Mayors. Kokumin-fuzai no shinsenmoni-seido wo kigushi sessoku ni susumeru kotoni hantaisuru kinkyu youbou (Objecting the new programs for producing specialist doctors. 2017. http://www.mayors.or.jp/p_opinion/documents/290412shinsenmoni_kinkyuyoubou.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2017).

- 11. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Shakai-hosyou-shingikai iryoubukai dai46kai gijiroku (Discussion record of the 46th meical group meeting of the Social Security Committee. 2016. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/gijiroku46.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2017).

- 12. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Shakai-hosyou-shingikai iryoubukai dai47kai gijiroku (Discussion record of the 47th meical group meeting of the Social Security Committee). 2016. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000149697.html (accessed 25 Apr 2017).

- 13. Association of Japan Medical Colleges. Heisei 28 nendo chiikiwaku-nyugaku-seido to chiiki-iryo-shien-senta no jitsujou ni kansuru chousahoukoku (Survey report on regional subquota admission and community health support centers in 2016). Tokyo: AJMC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Takeuchi K. Quality of care in Japan: an additional strategy. Lancet 2011;378:e17 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61841-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsumoto M, Takeuchi K, Tanaka J, et al. . Follow-up study of the regional quota system of Japanese medical schools and prefecture scholarship programmes: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011165 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsumoto M, Mizooka M, Tazuma S. General practice departments of university hospitals and certified training programs for general practitioners in Japan: a nationwide questionnaire survey. J Gen Fam Med 2017;18:244–8. 10.1002/jgf2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Heisei28nendo igakubu nyugakuteiinnzou ni tuite (Increase in the number of entrants to medical schools in 2016. 2016. http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/houdou/27/10/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2015/10/23/1363060_4_1.pdf (accessed 22 Jun 2016).

- 18. Sapix Yozemi Group. 2016-nendo kokukouritsudaigaku-nyushi joukyou to bunseki (Results and analysis of public medical school admission in 2016. 2016. http://juken.y-sapix.com/articles/3640.html (accessed 19 Aug 2017).

- 19. Sapix Yozemi Group. 2016-nendo shiritsudaigaku-nyushi joukyou to bunseki (Results and analysis of private medical school admission in 2016. 2016. http://juken.y-sapix.com/articles/3668.html (accessed 19 Aug 2017).

- 20. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Kokka-shiken-gokaku-happyou (Results of the national license examinations). 2017. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/kouseiroudoushou/shikaku_shiken/goukaku.html (accessed 15 Aug 2017).

- 21. TECOM Inc. Kokkashiken-jouhou dai 108-111 kai (Information on the 108th-111th national licese examinations). 2017. https://www2.tecomgroup.jp/igaku/topics/kokushi/ (accessed 15 Aug 2017).

- 22. Sakemi T. Heisei 14-15nendo igakubu-igakuka-nyugakusya no nyugakugo-seiseki ni kansuru bunseki (Academic performance of medical students after admission). Daigakukyouiku Nenpo 2010;6:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsumoto M, Kajii E. Medical education program with obligatory rural service: analysis of factors associated with obligation compliance. Health Policy 2009;90:125–32. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jichi Medical University. Syugaku-shikin, shogakushikin (Scholarship system). 2017. https://www.jichi.ac.jp/exam/medicine/campus/backup.html (accessed 15 Aug 2017).

- 25. Frehywot S, Mullan F, Payne PW, et al. . Compulsory service programmes for recruiting health workers in remote and rural areas: do they work? Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:364–70. 10.2471/BLT.09.071605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE. Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:86 10.1186/1472-6963-9-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, et al. . Outcomes of states’ scholarship, loan repayment, and related programs for physicians. Med Care 2004;42:560–8. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128003.81622.ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.