Abstract

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of death from cancer. Early diagnosis of LC is of paramount importance in terms of prognosis. The health authorities of most countries do not accept screening programmes based on low-dose chest CT (LDCT), especially in Europe, because they are flawed by a high rate of false-positive results, leading to a large number of invasive diagnostic procedures. These authorities advocated further research, including companion biological tests that could enhance the effectiveness of LC screening. The present project aims to validate early diagnosis of LC by detection and characterisation of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) in a peripheral blood sample taken from a prospective cohort of persons at high-risk of LC.

Methods and analysis

The AIR Project is a prospective, multicentre, double-blinded, cohort study conducted by a consortium of 21 French university centres. The primary objective is to determine the operational values of CTCs for the early detection of LC in a cohort of asymptomatic participants at high risk for LC, that is, smokers and ex-smokers (≥30 pack-years, quitted ≤15 years), aged ≥55 years, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The study participants will undergo yearly screening rounds for 3 years plus a 1-year follow-up. Each round will include LDCT plus peripheral blood sampling for CTC detection. Assuming 5% prevalence of LC in the studied population and a 10% dropout rate, a total of at least 600 volunteers will be enrolled.

Ethics and dissemination

The study sponsor is the University Hospital of Nice. The study was approved for France by the ethical committee CPP Sud-Méditerranée V and the ANSM (Ministry of Health) in July 2015. The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals and national and international conference presentations.

Trial registration number

Keywords: screening, lung cancer, copd, cytopathology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study focuses on an unmet need, that is, identification of persons at high risk for lung cancer (LC).

Previous results from our group suggest that circulating tumour cells (CTCs) is an early event in LC and therefore could be used as a screening tool for LC.

The main limitation is the insufficient power of this study to show a clinical benefit (ie, reduction of LC mortality).

Another limitation may be the detection of CTCs from a cancer developing in another organ (such as the bladder) in this high-risk population, although ancillary methods are under development to better characterise the origin of the detected CTCs.

Background and rationale

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of death from cancer. In France, LC is the first and second cause of cancer-related death in men and women, respectively, before prostate and colorectal cancers in men and after breast cancer in women.1 In 2015 for the first time, the LC death rate in women overtook that of breast cancer in some European countries (UK and Poland).2

Despite recent progress in therapeutic strategies, overall survival marginally decreased in the past 30 years, and almost all patients with a symptomatic LC die of their disease within 5 years of diagnosis.3 4 The main reason is that surgery can be offered to less than 25% of patients because more than 75% of LCs are diagnosed at advanced stages or are associated with comorbidities that contraindicate surgery.5 6

Beside tobacco control, screening for early stage LC makes great sense. The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), a methodologically rigorous trial conducted by the National Cancer Institute, provided evidence on the effect of low-dose chest CT (LDCT) screening on LC mortality.7 This trial conducted in patients aged 55 to 74 years, current or former smokers (at least 30 pack-years) who quitted within 15 years prior to recruitment, showed that LDCT screening decreased LC-specific mortality by at least 20% compared with chest X-ray screening. Several other LDCT screening trials are currently under way in Europe8 9 but may not reach definite conclusions.10

Implementation and generalisation of LDCT screening generates a substantial number of patients seeking advice for lung nodules of an undetermined nature and is therefore under debate.10 False-positive tests (ie, identified at least one nodule ≥4 mm in size) occur in close to one-third of LDCT screening examinations, and less than 3% of the patients who underwent the three rounds ultimately had a confirmed LC.7 11–13 In addition to generating anxiety and being costly, these ‘incidental’ nodules lead to multiple additional investigations that may per se be harmful to the patients. Even in North America, where LDCT screening is recommended, there is a large debate on improving the LC screening efficiency by (1) enhanced risk-based approaches, that is, focusing on the appropriate high-risk patients, such as patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)14–22; (2) setting more conservative thresholds for a positive nodule (eg, ≥6 mm) instead of the current ‘minimal size’ of 4 mm23or (3) development of novel biomarkers measured in different biological samples (eg, blood and urine) that improve the ability to predict LC risk24 or to distinguish benign from malignant screen-detected nodules. Non-invasive biomarkers under investigation include circulating tumour cells (CTCs),25 26 circulating specific non-protein-coding RNA27–29 and methylation of circulating DNA.30 Migration of CTCs into the blood stream is an early event of human carcinogenesis, and tumours measuring around 300 μm can be associated with the presence of CTCs. Up to now, CTCs have been mainly analysed in patients with an established diagnosis of cancer and used to monitor response to chemotherapy or to look for genomic alterations associated with a targeted therapy.25 31 32 We recently showed that in high-risk patients, that is, patients with COPD, CTCs detected with the isolation by size of epithelial tumour cell (ISET) technique (Rarecells) were present up to 4 years before LC was identified on LDCT.26 The CTCs detected had a heterogeneous expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers, which was similar to the corresponding lung tumour phenotype.33 No CTCs were detected in control smoking and non-smoking healthy individuals. With these preliminary results, we demonstrated for the first time that in high-risk patients, CTCs can be detected very early in the course of LC and, therefore, could be used as a screening tool in high-risk patients or be a biomarker that helps in focusing LDCT efforts on individuals who are at highest risk for LC. It also might help in distinguishing benign from malignant lesions in the patients who show lung nodules on LDCT in screening programme. To confirm these hypotheses, a national prospective cohort study will be run with high-risk participants.

Study design and objectives

The AIR Project is a prospective, non-randomised, multicentre, double-blinded, cohort study that evaluates CTCs as a screening tool for LC in a population at high risk. Study participants and investigators will be blinded to the results of the CTC analysis. On inclusion in the trial study, participants will undergo LDCT. In participants without prevalent cancer at baseline, two additional LDCTs, 1 and 2 years after baseline, will be offered for search of incidental cases. Search for CTC will be performed at baseline along with LDCT (±1 month of LDCT) and then one time per year for 2 years along with LDCT. The study sponsor is the University Hospital of Nice (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice). Twenty-one sites throughout France will participate in this study. The total duration is 4 years (inclusion period=16 months; follow-up=1 to 4 years; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02500693).

The primary objective is to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of CTCs for the early detection of LC in a cohort of asymptomatic participants at high risk for LC.

The secondary objectives are (1) to determine whether CTC and/or miRNA signature from plasma and/or DNA methylation from circulating free DNA can distinguish benign from malignant screen-detected pulmonary nodules in asymptomatic persons at high risk for LC, (2) to check whether the presence of CTCs should prompt a special follow-up in a population at high risk of LC with negative LDCT screening, (3) to study the relationship between the severity and the distribution of emphysema and LC development, (4) to study the exposure of the cohort to professional carcinogens and (5) to study the effect of screening on smoking behaviour in smokers and to study the psychological impact of LDCT detection of lung nodules.

Study population

The study population will consist of at least 600 participants who will be enrolled in 21 centres in France. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

*Compatible medical history and fixed airflow limitation as defined by postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7.39

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

The main inclusion criteria combine the NLST criteria,7 that is, age 55 years, tobacco pack-years ≥30, previous smoker, quit within 15 years and presence of COPD.

We chose to add the ‘COPD’ criteria because we aim to focus on a population at high risk for LC. In fact, accumulating data suggest that the presence of COPD or emphysema, not considered in the NLST trial,7 dramatically improves the selection process for LDCT cancer screening. For instance, it was shown that after adjusting for sex, age and history of smoking, COPD is associated with a twofold increase and emphysema with a threefold increase in the LC risk.16 18 20 34 35

Inclusion and procedures

Participants who meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria will be enrolled by a designated investigator from each centre, after signing written informed consent. Inclusion will be performed online (secured Internet protocol) using a dedicated web based platform; the participant’s inclusion number will be allocated online with the format: 00–00/centre number/number of inclusion. No randomisation is planned in this study. Participants and investigators are blinded to the results of CTC analysis.

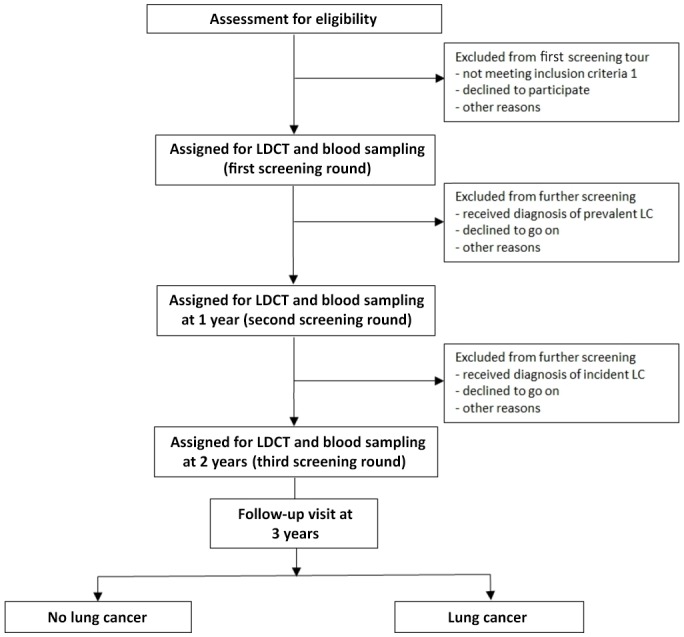

The study flow diagram is displayed in figure 1. After the assessment for eligibility, enrolled participants will undergo a LDCT and a blood test for CTC search (CTCs detected with the ISET technique (Rarecells)) once a year for 3 consecutive years. Participants will be excluded from further screening when diagnosed with LC after an LDCT. All participants will be followed for at least 1 year after the last screening tour.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the AIR Project. LC, lung cancer; LDCT, low-dose chest CT.

For LDCT, multidetector scanners (≥16 detectors) will be used to ensure that the whole chest can be scanned in a single maximal breath hold. Unenhanced acquisitions (ie, without contrast media) will use a low radiation exposure protocol consistent with LC screening protocols with flexibility for making adjustments based on the participants’ body mass index (BMI). The tube voltage will range from 100 to 140 kVp, and the effective tube current time product will range from 20 to 60 mAs, according to the participants’ BMI and on the CT apparatus. Each low-dose CT will result in an average effective dose ≤1.5 mSv,36 37 for an average 70 kg adult. T corresponds to a dose length product of about 75 mGy-cm.

During each round, 20 mL of peripheral blood on Streck tubes (Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes; Streck, Omaha, Nebraska, USA) will be taken from each participant. These tubes will be sent at ambient temperature to the coordinator centre (Nice Biobank) within 48 hours. ISET will be carried out as previously described.26 To compare the immediate delayed filtration, during the first round, the coordinator centre (Nice) and the four other centres equipped with the ISET machines (Strasbourg, Toulouse, Nancy and Grenoble) will collect an additional 10 mL in an EDTA tube, which will be processed for immediate ISET filtration. The ISET non-coloured filters, stored at 4°C, will be shipped later to the coordinator centre for further CTC analysis.

Management of radiologically significant incidental findings

As in the NLST trial,7 no formal recommendation will be made as to how a suspicious lesion should be managed in each centre. For the management of a suspicious lesion, all the centres involved in the present study will follow the strategies recommended by the French thoracic oncology groups35 and the Fleischner society.38 However, specific clinical presentations may fall outside of this general approach and may require specific discussion in a multidisciplinary team meeting, which is the standard of care in all the centres involved in the present study.

Outcomes

The primary end point will be evaluated at the end of the follow-up period and will be represented by the rate of detection of CTCs in participants for whom LC is detected during the study.

The secondary end points will include the following: (1) rate of detection of CTCs in the whole study population, (2) predictive value of CTC detection for the diagnosis of LC in participants identified as having a pulmonary nodule, (3) time span between detection of CTC and detection of LC with LDCT and vice versa, (4) microRNA and DNA methylation profile in the study population, (5) smoking cessation rate and (6) pretest or post-test changes in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale.

For participants for whom a suspicious lung nodule has been identified and in whom a final and definite diagnosis of cancer cannot be established because of premature death, a dedicated adjudication committee will review the entire medical chart and available documents to establish the probability of cancer.

Two interim analysis are planned, one at the end of the first screening tour and one at the end of the second one, in order to check whether the number of cases with CTCs is significantly higher than we would expect.

Collection of data and monitoring

The usual demographic data will be recorded. The COPD phenotype will be recorded and thus will include measurement of airflow limitation by pulmonary function tests and assessment of COPD severity by the ABCD grading system (ie, the ABCD grading system considers COPD symptoms along with the exacerbation frequency and severity: A is better, and D is worse).39 Professional exposure to carcinogens will be evaluated with the RECAP questionnaire.40 Lastly, the HAD scale will be measured during each protocol visit.

An electronic case report form has been created and is connected to a dedicated web-based biobank management module (Biobank 06, Nice and Naeka, Grenoble, France).

All chest CT will be anonymised and stored in electronic (DICOM) format for further centralised analysis.

Quality control will be done by clinical research monitors appointed by the sponsor. The nature and frequency of monitoring will be based on the rate of inclusion. They will check for the accuracy and completeness of the Case Report Form entries, source documents and other trial-related records. They will verify that written informed consent was obtained and that the trial is in compliance with the currently approved protocol/amendment(s) in each centre, with good clinical practice and with the applicable regulatory requirement(s).

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) is defined as any untoward medical occurrence occurring during the participation of a subject in the trial, independently of the relationship with the study-related interventions and procedures. A serious adverse event (SAE) is defined as any AE that results in death, is life-threatening, requiring participants’ hospitalisation or prolongation of an existing hospitalisation and results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity. Each AE must be judged by the investigator and the sponsor, for assessment of the severity of the causal link between AE and the procedure and the character expected or unexpected. A suspected unexpected severe adverse reaction is an adverse reaction that is both unexpected (not consistent with the study-related interventions and procedures) and also meets the definition of an SAE. According to the law of 9 August 2004 of the Code of Public Health, any occurrence of an SAE will immediately be reported to the sponsor. The sponsor will declare SAE likely to be related to biomedical research to the EC and to the French Agence Nationale du Medicament et des produits de Santé (ANSM) without delay and no later than 7 calendar days in case of death or life-threatening and without delay and at the latest within 15 days for the other SAE.

Statistical analysis and sample size

Statistical analyses will be performed on the whole study population, those with LC (LC positives) and those without (LC negatives), detected by means of LDCT or by any others means. Data from both groups will be summarised separately for all criteria, demographics and baseline characteristics by descriptive statistics. A flow diagram presenting the progress of both groups throughout the study (enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up and techniques for definite LC diagnosis) in each case will be displayed. The sensitivity and specificity of the ISET technique (detection of CTCs) for the detection of LC will be determined and presented with their 95% CI based on the Wilson score calculation method. PPV and NPV will be estimated assuming a 5% prevalence of LC in the studied population. The PPV and NPV of detection of CTCs for diagnosing LC in the participants for whom clinically significant incidental findings will be revealed during the study course will be calculated, assuming a 25%–35% prevalence of such findings in the studied population. In the LC-positive group, descriptive statistics describing the temporal relationship (first sign suggestive of LC) and positivity of CTC detection will be provided. Test assumptions will be verified before analyses. The p values below 0.05 will be considered to denote statistical significance. Based on the prevalence (baseline screening round) and incidence (repeat screening rounds) of LC in this high-risk population and considering a 10% dropout rate, if we aim to study a total of 25–35 detected LC, including baseline and repeat screening rounds, we need to enrol a total of 600 participants.

Ethics, regulatory clearances and dissemination

Liability insurance: Hospital Mutual Insurance Company (SHAM no 145.017); ClinicalTrial.gov no : NCT02500693. ISET-Rarecells CE mark was obtained on 12 May 2013. A steering committee has been set up to monitor ethical aspects of the project. The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals and national and international conference presentations.

Milestones

The first study participant was enrolled on 30 October 2015; last participant was enrolled (cohort completed) on 28 February 2017. The last follow-up visit of the last enrolled participant is on February 2020.

Discussion

The AIR Project is the first study to prospectively assess the value of CTC detection for LC screening. We expect that in this high-risk population, CTC detection (via the ISET technology) will improve the detection rate of LC and perhaps also reduce the rate of false-positive chest CT by distinguishing benign from malignant screen-detected pulmonary nodules in persons at high risk for LC. Concurrent biomarker analysis (miRNA and DNA methylation) in blood samples may also offer the opportunity to validate a multimodal signature predictive of LC in a high-risk populations with screen detected pulmonary nodules.

The main limitation of this study is that LC-related mortality will not be assessed as the primary outcome. Therefore, the power of this study may not be adequate to show a clinical benefit. Another limitation may be the detection of CTCs from a cancer developing in another organ (such as the bladder) in this high-risk population. However, ancillary methods are under development to better characterise the origin of the detected CTCs.33

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank especially B Pollner, B Faidhi and I Kondratyeva for their generous contribution to the realisation of this study.

Footnotes

SL, JB, PH and CHM contributed equally.

Contributors: SL, CHM, PH, VH, MI, JB, BP and AM designed the study and protocol submission. SL, CHM and PH wrote the manuscript. DI-B, CP, PC, JC and JM revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by public funding (Conseil Départemental 06, Fondation UNICE, Fondation de France, and Ligue Contre le Cancer -Comité des Alpes-Maritimes).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Ethics Committee approval (CPP Sud Méditerranée V on 5 July 2015 (registration no 15.072) and ANSM (Ministry of Health) authorisation were obtained on 8 and 10July 2015.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: The members of the AIR Project Study Group include all authors and François Chabot, MD (HôpitalUniversitaire de Nancy); Gaetan Deslee, MD; Jeanne Marie Perotin, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Reims); Hervé Mal, MD (Hôpital Bichat); Romain Kessler, MD (Hôpital Universitaire deStrasbourg); Jean-Michel Vergnon, MD; Isabelle Pelissier, MD (HôpitalUniversitaire de St Etienne); Antoine Cuvelier, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Rouen); Arnaud Bourdin, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Montpellier); Nicolas Roche, MD (Hôpital Cochin); Stephane Jouneau, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Rennes); Philippe Bonniaud, MD; Ayoube Zouak, MD (HôpitalUniversitaire de Dijon); Arnaud Scherpereel, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Lille); Jean Francois Mornex, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Lyon); Francois Steenhouwer, MD (Hôpital de Roubaix); Johanna Pradelli, MD; Maureen Fontaine; Jennifer Griffonnet; Ariane Guillemart (Hôpital Universitaire deNice); Catherine Butori, MD; Eric Selva(Hôpital Universitaire de Nice); Laurent Plantier, MD; Gaelle Fajolle, MD;Melanie Rayez, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Tours); Vincent Falle, MD;Nouha Chaabane, MD; Anne Marie Ruppert, MD (Hôpital Tenon); Damien Rouviere, MD; Emilie Bousquet, MD (HôpitalUniversitaire de Toulouse); Faiza Bentayeb, MD; Laurie Pahus, PharmD (Hôpital Universitaire de Marseille); Bernard Aguilaniu, MD; Gilbert Ferretti, MD; and Anne-ClaireToffart, MD (Hôpital Universitaire de Grenoble).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the AIR Project Study Group, François Chabot, Gaetan Deslee, Jeanne Marie Perotin, Hervé Mal, Romain Kessler, Jean-michel Vergnon, Isabelle Pelissier, Antoine Cuvelier, Arnaud Bourdin, Nicolas Roche, Stephane Jouneau, Philippe Bonniaud, Ayoube Zouak, Arnaud Scherpereel, Jean Francois Mornex, Francois Steenhouwer, Johanna Pradelli, Maureen Fontaine, Jennifer Griffonnet, Ariane Guillemart, Catherine Butori, Eric Selva, Laurent Plantier, Gaelle Fajolle, Melanie Rayez, Vincent Falle, Nouha Chaabane, Anne Marie Ruppert, Damien Rouviere, Emilie Bousquet, Faiza Bentayeb, Laurie Pahus, Bernard Aguilaniu, Gilbert Ferretti, and Anne-claire Toffart

References

- 1. INCA. Cancers in France in 2016: the main facts and figures, 2017. http://www.e-cancer.fr/Actualites-et-evenements/Actualites/Les-cancers-en-France-en-2016-l-essentiel-des-faits-et-chiffres

- 2. Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Rosso T, et al. . European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2015: does lung cancer have the highest death rate in EU women? Ann Oncol 2015;26:779–86. 10.1093/annonc/mdv001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanchon F, Grivaux M, Asselain B, et al. . 4-year mortality in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: development and validation of a prognostic index. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:829–36. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70868-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2016. SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, April 2017 https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgensztern D, Ng SH, Gao F, et al. . Trends in stage distribution for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a national cancer database survey. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:29–33. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c5920c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Locher C, Debieuvre D, Coëtmeur D, et al. . Major changes in lung cancer over the last ten years in France: the KBP-CPHG studies. Lung Cancer 2013;81:32–8. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. . Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395–409. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Field JK, van Klaveren R, Pedersen JH, et al. . European randomized lung cancer screening trials: Post NLST. J Surg Oncol 2013;108:280–6. 10.1002/jso.23383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manser R, Lethaby A, Irving LB, et al. . Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;6:CD001991 10.1002/14651858.CD001991.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. HAS. Pertinence du dépistage du cancer broncho-pulmonaire en France - Point de situation sur les données disponibles - Analyse critique des études contrôlées randomisées, 2016. http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_2001613/fr/pertinence-du-depistage-du-cancer-broncho-pulmonaire-en-france-point-de-situation-sur-les-donnees-disponibles-analyse-critique-des-etudes-controlees-randomisees.

- 11. Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. . Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 2012;307:2418–29. 10.1001/jama.2012.5521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berg CD, Aberle DR, Wood DE. Lung cancer screening: promise and pitfalls. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2012:450-7 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, et al. . Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1980–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Torres JP, Bastarrika G, Wisnivesky JP, et al. . Assessing the relationship between lung cancer risk and emphysema detected on low-dose CT of the chest. Chest 2007;132:1932–8. 10.1378/chest.07-1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Y, Swensen SJ, Karabekmez LG, et al. . Effect of emphysema on lung cancer risk in smokers: a computed tomography-based assessment. Cancer Prev Res 2011;4:43–50. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Young RP, Hopkins RJ. Diagnosing COPD and targeted lung cancer screening. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1063–4. 10.1183/09031936.00070012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arenberg D. Searching for red shirts. Emphysema as a lung cancer screening criterion? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:868–9. 10.1164/rccm.201502-0381ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de-Torres JP, Wilson DO, Sanchez-Salcedo P, et al. . Lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Development and validation of the COPD Lung Cancer Screening Score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:285–91. 10.1164/rccm.201407-1210OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowry KP, Gazelle GS, Gilmore ME, et al. . Personalizing annual lung cancer screening for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a decision analysis. Cancer 2015;121:1556–62. 10.1002/cncr.29225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sanchez-Salcedo P, Wilson DO, de-Torres JP, et al. . Improving selection criteria for lung cancer screening. The potential role of emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:924–31. 10.1164/rccm.201410-1848OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katki HA, Kovalchik SA, Berg CD, et al. . Development and validation of risk models to select ever-smokers for CT lung cancer screening. JAMA 2016;315:2300–11. 10.1001/jama.2016.6255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. NCCN guidelines version 1. Lung cancer screening, 2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf

- 23. Yip R, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. . CT screening for lung cancer: alternative definitions of positive test result based on the National Lung Screening Trial and International Early Lung Cancer Action Program databases. Radiology 2014;273:591–6. 10.1148/radiol.14132950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vachani A, Sequist LV, Spira A. AJRCCM: 100-year anniversary. The shifting landscape for lung cancer: past, present, and future. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:1150–60. 10.1164/rccm.201702-0433CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ilie M, Hofman V, Long E, et al. . Current challenges for detection of circulating tumor cells and cell-free circulating nucleic acids, and their characterization in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients. What is the best blood substrate for personalized medicine? Ann Transl Med 2014;2:107 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.08.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ilie M, Hofman V, Long-Mira E, et al. . "Sentinel" circulating tumor cells allow early diagnosis of lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e111597 10.1371/journal.pone.0111597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazières J, Catherinne C, Delfour O, et al. . Alternative processing of the U2 small nuclear RNA produces a 19-22nt fragment with relevance for the detection of non-small cell lung cancer in human serum. PLoS One 2013;8:e60134 10.1371/journal.pone.0060134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montani F, Marzi MJ, Dezi F, et al. . MiR-Test: a blood test for lung cancer early detection. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107 10.1093/jnci/djv063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hofman P. Liquid biopsy for early detection of lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2017;29:73–8. 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu Y, Li S, Zhu S, et al. . Methylated DNA/RNA in body fluids as biomarkers for lung cancer. Biol Proced Online 2017;19:2 10.1186/s12575-017-0051-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hofman V, Bonnetaud C, Ilie MI, et al. . Preoperative circulating tumor cell detection using the isolation by size of epithelial tumor cell method for patients with lung cancer is a new prognostic biomarker. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:827–35. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ilie M, Long E, Butori C, et al. . ALK-gene rearrangement: a comparative analysis on circulating tumour cells and tumour tissue from patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2907–13. 10.1093/annonc/mds137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hofman VJ, Ilie M, Hofman PM. Detection and characterization of circulating tumor cells in lung cancer: Why and how? Cancer Cytopathol 2016;124:380–7. 10.1002/cncy.21651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Balkan A, et al. . Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:738–44. 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith BM, Pinto L, Ezer N, et al. . Emphysema detected on computed tomography and risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2012;77:58–63. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Couraud S, Cortot AB, Greillier L, et al. . From randomized trials to the clinic: is it time to implement individual lung-cancer screening in clinical practice? A multidisciplinary statement from French experts on behalf of the French intergroup (IFCT) and the groupe d’Oncologie de langue francaise (GOLF). Ann Oncol 2013;24:586–97. 10.1093/annonc/mds476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lederlin M, Revel MP, Khalil A, et al. . Management strategy of pulmonary nodule in 2013. Diagn Interv Imaging 2013;94:1081–94. 10.1016/j.diii.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. . Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the fleischner society 2017. Radiology 2017;284:228–43. 10.1148/radiol.2017161659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD, 2017. http://goldcopd.org

- 40. Pélissier C, Dutertre V, Fournel P, et al. . Design and validation of a self-administered questionnaire as an aid to detection of occupational exposure to lung carcinogens. Public Health 2017;143:44–51. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.