Abstract

Purpose:

This study examines whether cognitive function, as measured by the subtests of the Woodcock–Johnson III (WCJ-III) assessment, predicts listening-effort performance during dual tasks across the adults of varying ages.

Materials and Methods:

Participants were divided into two groups. Group 1 consisted of 14 listeners (number of females = 11) who were 41–61 years old [mean = 53.18; standard deviation (SD) = 5.97]. Group 2 consisted of 15 listeners (number of females = 9) who were 63–81 years old (mean = 72.07; SD = 5.11). Participants were administered the WCJ-III Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, Visual Matching, and Decision Speed subtests. All participants were tested in each of the following three dual-task experimental conditions, which were varying in complexity: (1) auditory word recognition + visual processing, (2) auditory working memory (word) + visual processing, and (3) auditory working memory (sentence) + visual processing in noise.

Results:

A repeated measures analysis of variance revealed that task complexity significantly affected the performance measures of auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and processing speed. Linear regression revealed that the cognitive subtests of the WCJ-III test significantly predicted performance across dependent variable measures.

Conclusion:

Listening effort is significantly affected by task complexity, regardless of age. Performance on the WCJ-III test may predict listening effort in adults and may assist speech-language pathologist (SLPs) to understand challenges faced by participants when subjected to noise.

Keywords: Aging, cognitive function, dual-task, listening effort, task complexity, working memory

Introduction

Recent research investigating listening effort during the performance of dual tasks has established that cognition and hearing function are tightly linked.[1,2,3,4,5] Specifically, working memory, attention, and processing speed have been identified as the dominant cognitive processes, or mental skills, which support auditory processing for speech perception.[6,7,8,9] Although cognitive and auditory resources contribute to the skills utilized to process auditory information, cognitive screens to determine function have not been routinely adopted in audiologic clinics, nor have they been consistently employed in research on cognition and listening effort. The purpose of this study was to explore whether cognitive screenings regularly performed by speech language pathologists could be used to predict listening effort in older listeners. Exploring the link between cognitive assessments (routinely used by speech-language pathologist, SLPs) and listening effort may contribute to our understanding of how noise and task difficulty during dual-task performance may influence older listeners.

Listening effort refers specifically to the mental skills, including attention, needed to understand speech.[1,2,4,10,11,12] Dual-task paradigms (DTPs) have been used successfully to study the complex and contradictory relationship between cognition and listening effort.[1,2,4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Although the employment of dual-task methodology remains highly variable across fields and warrants further exploration for the most efficacious, hierarchical use, the purpose of the current study is to explore a possible predictive relationship between cognitive function and dual-task performance.

Gosselin and Gagné[1] used DTPs to study listening effort in noise across the young (18–33 years old) and older (64–76 years old) groups of listeners. All participants demonstrated hearing and cognitive functions within normal limits during screenings. Cognitive function was established using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Participants were then administered the following three experimental conditions: (1) “closed-set sentence recognition in noise” (primary task), (2) “tactile pattern recognition in quiet” (secondary task), and (3) both the primary and secondary tasks completed simultaneously (dual task).[1 (p. 789)] During the practice session, noise levels were set for 80% performance accuracy. Results indicated that older adults exhibited increased listening effort when compared to younger adults using the dual-task methodology. Specifically, results revealed decreased performance for both accuracy and processing speed across task complexity in the older adult group. These findings suggest that older adults use more cognitive resources to identify speech, with decreased resources for additional tasks.[1] While researchers did establish participant cognitive function via the MoCA, they did not utilize a screening tool designed to assess the specific cognitive skills activated during speech in noise tasks, nor did they explore whether the cognitive function predicted listening effort performance. Specifically, the MoCA is a screening tool for mild cognitive dysfunction.[19] The MoCA is designed to screen general cognitive status, and, therefore, does not provide a rigorous assessment of the cognitive skills of working memory, sustained attention, and processing speed attention,[6,8] which are known to be activated during speech perception in noise (SPIN).

A more recent study by Degeest et al.[20] investigated the effects of age on listening effort using dual-task methodologies in 60 normal-hearing listeners ranging in age from 20 to 77 years. As in the Gosselin and Gagné[1] study, participants were screened for normal cognitive function using the MoCA; however, only participants over the age of 60 years were subjected to this screening. Participants then completed the following three experimental conditions: (1) a primary speech-recognition task in noise, (2) a secondary visual memory task, and (3) the primary and secondary tasks concurrently. Results showed that not only does listening effort increase with age, but listening effort performance begins to show greater challenge starting in the fourth decade of life, even when hearing function is accounted for. Because Degeest et al.[20] only screened cognition in participants over the age of 60 years, it is unclear whether changes in cognitive function may have been influencing the listeners below that age. Because normal cognitive decline with age can begin as early as 45 years,[21] some participants may have demonstrated undocumented typical cognitive decline with age. Therefore, increases in listening effort in younger individuals may be due to undocumented cognitive decline. Further, the MoCA is a general cognitive screener and is not designed to assess cognitive skills contributing to listening effort.

The purpose of the current study is to examine the relationship between cognitive subtests and performance during dual tasks. Specifically, do the Woodcock–Johnson III (WCJ-III) subtests of Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, Visual Matching, and Decision Speed predict auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and visual reaction time during complex tasks? We hypothesized that cognitive function would predict performance across age groups. If cognitive function predicts performance during dual task, this may provide insight regarding the types of tasks that should be included in cognitive screeners for audiologic and speech pathology services.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-nine native speakers of American English were divided into two groups based on their age. Group 1 included 14 participants (number of females = 11; number of males = 4), aged 41–61 years old [mean = 53.18; standard deviation (SD) = 5.97]. Group 2 included 15 participants (number of females = 9; number of males = 6), aged 63–81 years old (mean = 72.07; SD = 5.11). All participants demonstrated normal to near-normal hearing and normal middle ear function on audiometric assessment. Normal to near-normal hearing criterion included thresholds less than or equal to 35 dB HL from 250 to 3000 Hz.[8] The mean four-frequency pure tone average (PTA) for the right and left ears for Group 1 were 17.18 dB HL (SD = 6.11), and 15.98 dB HL (SD = 6.60), respectively. The mean four-frequency PTA for the right and left ears for Group 2 were 22.67 dB HL (SD = 5.89), and 21.42 dB HL (SD = 7.62), respectively.

Cognitive function was examined utilizing a screening battery of standardized cognitive subtests compiled from the WCJ-III[22] test of cognitive abilities. The four subtests (Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, Decision Speed, and Visual Matching) provided a baseline for the functions of processing speed and working memory across auditory and visual tasks. The Memory for Words subtest was utilized to examine participants’ short-term memory, specifically auditory memory span. For this subtest, participants repeat aurally presented sequences of up to seven unrelated words in the same order they were presented. The Auditory Working Memory subtest also examined short-term memory, specifically working memory and cognitive processes responsible for the recoding of acoustic stimuli.[23] The task involves retaining two types of information (words and numbers) presented orally in a mixed order and then reordering that information and repeating first the words and then the numbers. The Visual Matching subtest is used to assess perceptual speed for visual stimuli. Perceptual speed involves making comparisons on the basis of rapid visual searches. In this subtest, participants are presented with 60 printed sets of six numbers and are directed to identify (and circle) two identical numbers within each set, within 3 min. The six number sets range from single- to triple-digit numbers. Finally, the Decision Speed subtest is a timed task that tests processing speed, specifically semantic processing speed (symbolic and semantic comparisons).[23] In this subtest, participants are presented with sets of seven pictures, and for each set, participants are instructed to circle the two drawings that are the most closely associated. They are given 3 min to complete 40 printed sets. In accordance with WCJ-III standardized administration instructions, the Memory for Words and Auditory Working Memory subtests were not timed. The Decision Speed and Visual Matching subtests were timed tasks, but reaction time was not recorded. This screening battery provided baselines for the basic functions of processing speed and working memory using both visual and auditory tasks for each participant. Cognitive function inclusion criterion stipulated that participants needed to achieve standard scores greater than 85 on at least three of the four subtests to participate in the study. Participants completed a self-report, verifying normal or corrected vision (e.g., glasses or contacts). The standardized Edinburgh Handedness Inventory was used to establish participant handedness, wherein right-handedness is shown by a score >40.[24] Twenty-six participants were right handed, two were ambidextrous, and one participant was left-handed. All participants signed consent forms prior to participating in the protocol. This project was approved by The University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s Institutional Review Board.

Materials and Procedure

General description of task conditions

All participants completed each of the experimental conditions. The three experimental conditions employed a DTP including both auditory and visual processing in noise. The simple dual-task condition examined visual processing speed and auditory speech perception. The moderate dual-task condition involved visual processing and auditory word recall (words in isolation). The complex dual-task condition examined visual processing and working memory for auditorily presented words in the context of a sentence. The conditions were created to denote a hierarchical progression in the complexity of each skill set, engaging working memory in the higher-level conditions.[1,4,5,11,25] Task complexity was manipulated in the following two modalities: controlling the level of listening effort by increasing the amount of resources needed and the variation of the listening condition. The inclusion of the moderate task and 3-dB listening condition may provide insight into the more subtle changes to dual-task performance. The basic level in this progression was the simple dual-task condition, which involves completing a visual task and a word recognition task concurrently. Participants were asked to identify a word immediately after hearing it, which is considered a basic recognition task. In the moderate dual-task condition, participants were directed to maintain the words in memory prior to repeating them. This task taps into word recall and is more difficult than the simple dual-task condition. The complex dual-task condition was the most complex condition. During this task, participants were instructed to recall sets of words presented in sentences, in contrast to remembering words in isolation. All of these tasks were presented under varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs; 5, 3, and 0 dB SNR). All SNR levels (5, 3, and 0 dB SNR) were presented across each of the task conditions. Differences in accuracy and reaction time performance across the levels of SNR were calculated as the measures of listening effort. The experimental conditions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions

| Experimental conditions | Cognitive skills | Listening condition |

|---|---|---|

| Simple dual task | Word identification + visual processing speed | 0, 3, and 5 dB SNR |

| Moderate dual task | Working memory (word list) + visual processing speed | 0, 3, and 5 dB SNR |

| Complex dual task | Working memory (sentences) + visual processing speed | 0, 3, and 5 dB SNR |

The least challenging SNR was 5 dB, with the most difficult SNR at 0 dB. During each dual task, complexity was modified by altering the auditory task, with the visual task remaining unaltered. All experimental conditions were randomized for each participant. As a result, some participants began with the complex dual-task condition, while others started with the simple or moderate dual-task conditions.

Auditory task: stimuli

Both the simple and complex dual-task conditions used the tape-recorded revised SPIN (SPIN-R) test materials[26,27] for the auditory stimuli. The SPIN-R materials include eight word lists (50 sentences each) equally balanced for contextual predictability. Both the simple and complex dual-task conditions required complete sentence lists. Three SPIN-R lists were assigned to each of the conditions, following the randomization of all eight lists. Therefore, each participant was assigned six randomized SPIN-R sentences.

The moderate dual-task condition utilized the audio-recorded CID W-22 materials.[28] The CID W-22 materials consist of four recorded lists (50 words per list). While the CID W-22 lists originally included a carrier phrase before each word (e.g., “Say the word ‘an’”), the carrier phrase was eliminated. The target word was then the only word presented (e.g., “Day, Toe, Felt, Stove”). This modification was completed to account for any possible sentence context effects as a result from the carrier phrase.

Auditory task: procedure

The SNR conditions (5, 3, and 0 dB SNR) were presented during each of the dual-task conditions. The SPIN-R multitalker bab;1;ble was utilized as the competing noise. Specifically, the noise was modified to effect the previously mentioned SNRs, with the presentation level for speech set at 65 dB SPL. All testing was administered in a double-walled, sound-attenuating booth. The SPIN-R sentences, as well as the added CID W-22 word lists, were presented binaurally through insert earphones EAR-3A (Etymotic Research Inc., Elk Grove Village, IL, USA) routed through a Grason-Stadler 61 (Grason-Stadler Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA), two-channel audiometer. All of the following were randomized for each participant: experimental conditions (simple dual task, moderate dual task, and complex dual task), listening conditions (0, 3, and 5 dB SNR), SPIN-R sentence list, and CID W-22 word list.

Visual task: stimuli

In addition to completing the auditory task, participants were asked to execute a visual task concurrently. Participants were directed to observe a visual field on a 15-inch computer monitor and indicate via button press when a target letter appeared in a randomized series of letters. All letters, created using the SuperLab 4.5 software,[29] were presented in mid-field, with size 40 black font capital letters contrasted against a white background. The letters were presented on the screen for a maximum of 1500 ms time limit or until the participant completed the button press, whichever occurred first. The letter was automatically erased after each letter stimulus. The visual task began with the auditory task, and continued until the auditory task was finished. Approximately 290 letters and the target letter appeared a minimum of 30 times and a maximum of 40 times during the simple dual-task condition. For the moderate and complex dual-task conditions, the presentation of the visual task stimuli differed in agreement with the length of the auditory task presentations. For example, in the moderate and complex dual-task condition, the participants were administered different numbers of stimuli depending upon their working memory capacity, whereas, for the simple dual-task condition, the entire list of 50 sentences was presented to all participants. Therefore, the visual task stimuli presentation length ranged in accordance with the number of stimuli administered during the working memory task.

Visual task: procedure

During each of the dual-task conditions, the three SNR conditions (5, 3, and 0 dB SNR) were tested. A randomized target letter was selected for each of the SNR conditions. Participants were directed to monitor the computer screen and press the response button as soon as they identified the predetermined target letter. Each participant first received written instructions, which were verbally reinforced when the researcher read the instructions aloud. All participants indicated they understood the task prior to the start of the experiment. The instructions and target letter were presented on the computer screen prior to each listening condition. A small break was provided to reinstruct the participant with the new target letter for each listening condition (0, 3, and 5 dB SNR). Visual processing speed (reaction time to letter presentation as measured by button press) and visual accuracy (correct identification of target letter) responses were recorded for each trial. Processing speed data, for accurate responses only, were examined during analyses.

This section has provided a description of the stimuli and procedures for the individual auditory and visual tasks. The details of each of the dual-task experimental conditions are in the following sections.

Simple dual-task condition

The simple dual-task condition consisted of performing the visual letter identification task while concurrently completing the auditory word recognition task in noise. Participants were instructed to repeat the final word heard in a sentence while simultaneously identifying a target letter presented in the visual display monitor. All participants received written and verbal instructions read aloud by the researcher. Participants indicated that they understood the task prior to the start of the experiment. All participants completed this dual task under all three SNR conditions. For each visual processing condition, we recorded visual processing speed and percent visual accuracy letter identification; for each listening condition, we recorded percent correct auditory word recognition.

Moderate dual-task condition

For the moderate dual-task condition, a working memory (isolated words) task and visual processing speed task were completed concurrently. Word list sequences presented words in list sets of 2, 4, 6, and 8 recall levels. For each level of recall (2, 4, 6, or 8), participants were given one set of word lists at a time. Two word list sets needed to be successfully completed prior to progressing to the next set level of recall. For example, a participant received one set of two words, and then was instructed to recall the set. Upon correct recall of the first set of two words, the participant would then receive the second set of two words. If the participant was able to correctly recall the second set of two words, then the set size level of recall would be complete. The set size of recall would then progress to four word sets. Thus, to progress to the next set size level of recall, the participant had to correctly recall both sets of words for each set level [i.e., 1 set of 2 (twice), 1 set of 4 (twice), 1 set of 6 (twice), and 1 set of 8 (twice)]. If one of the words in a set was incorrect, the set ended, and the next set condition was administered. Each set condition received a percent correct score. The set score was calculated by dividing the total number of words that were correctly recalled by the maximum number of words presented (32 words) times one hundred, for each participant. Potentially, participants could receive a maximum of 40 words, if they achieved the eight-item level. As a result, not all participants were presented with equal numbers of sentences. Visual processing measures included percent correct letter identification and processing speed for accurate visual responses.

In summary, participants were asked to listen to the presented word list set and then verbally recall each word heard in the set. Any order of recall was accepted, but participants were instructed to recall the word list set in order if possible. If the word list set was correctly recalled for both sets in the recall level, then the participant progressed to the next level in the word list set recall hierarchy. Additionally, the previously described visual processing task was simultaneously performed. All participants received written and verbal instructions read aloud by the researcher. Participants indicated that they understood the task prior to the start of the experiment.

Complex dual-task condition

The complex dual-task condition involved completing the Auditory Working Memory task (words in sentence context) and performing the visual task simultaneously. The procedures for this condition were adapted from Daneman and Carpenter[30] procedures for assessing working memory and were used in the preliminary study. The SPIN-R sentences were utilized to examine working memory span for the sets of 2, 4, 6, and 8 sentences. The same procedures as described in the previous moderate dual-task condition section were used for the list sets of 2, 4, 6, and 8 recall levels. Participants were instructed to listen to a set of sentences and were asked to recall the final word of each of the sentences in the set. Participants needed to correctly recall both sets of final words in each sentence within each level. Again, similar to the moderate dual-task condition, if one of the words in a set was incorrectly recalled, the set ended, and the next set condition was administered. The scoring calculation was the same as described in the above section. As noted in earlier conditions, not all participants were presented with equal numbers of sentences. Visual processing measures included percent correct letter identification and processing speed (for accurate visual responses).

In summary, as in the moderate dual-task condition, participants were asked to listen to the presented sentence list set and then verbally recall each of the final words heard in the set. Participants were instructed to recall the word list set in order if possible, but any order was acceptable. If the sentence list set was correctly recalled for both sets in the recall level, then the participant progressed to the next level in list set recall hierarchy. Additionally, previously described visual processing task was simultaneously performed. All participants received written and verbal instructions read aloud by the researcher. Participants indicated that they understood the task prior to the start of the experiment.

Results

The current study investigated a relationship between cognitive function and performance during three levels of dual-task complexity (DT) (simple, moderate, and complex dual tasks) and by three levels of noise (5 dB SNR, 3 dB SNR, and 0 SNR). Three separate repeated measure ANOVAs were conducted for auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and processing speed measures across DT, noise, and group conditions. Further, multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to predict dual-task performance from cognitive function. Arcsine transformation was conducted for all percent accuracy scores prior to analysis to stabilize the variance. The mean data (auditory and visual) for the simple, moderate, and complex DT conditions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dual task auditory, visual accuracy, and speed average scores

| Listening condition | Auditory accuracy (%) | Visual accuracy (%) | Speed (ms) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||

| Simple | ||||||||||

| 5 dB | 96.80% | 93.87% | 93% | 99% | 610.09 | 593.92 | ||||

| (SD = 0.03) | (SD = 0.04) | (SD = 0.22) | (SD = 0.02) | (SD = 229.85) | (SD = 95.69) | |||||

| 3 dB | 94.27% | 91.20% | 99% | 97% | 559.71 | 6176.18 | ||||

| (SD = 0.05) | (SD = 0.06) | (SD = 0.02) | (SD = 0.06) | (SD = 88.97) | (SD = 104.63) | |||||

| 0 dB | 92.13% | 88.67% | 98% | 98% | 565.83 | 661.53 | ||||

| (SD = 0.05) | (SD = 0.06) | (SD = 0.03) | (SD = 0.04) | (SD = 95.14) | (SD = 216.69) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||||||

| 5 dB | 19.42% | 16.46% | 85% | 94% | 787.39 | 721.80 | ||||

| (SD = 24.58) | (SD = 20.07) | (SD = 0.21) | (SD = 0.10) | (SD = 223.38) | (SD = 130.78) | |||||

| 3 dB | 8.26% | 16.30% | 90% | 91% | 726.39 | 788.26 | ||||

| (SD = 5.96) | (SD = 12.51) | (SD = 0.18) | (SD = 0.18) | (SD = 173.52) | (SD = 270.48) | |||||

| 0 dB | 18.97% | 10.21% | 88% | 75% | 725.64 | 839.98 | ||||

| (SD = 0.15) | (SD = 9.02) | (SD = 0.22) | (SD = 0.38) | (SD = 281.106) | (SD = 348.45) | |||||

| Complex | ||||||||||

| 5 dB | 29.46% | 21.04% | 79.89% | 77.69% | 829.85 | 786.37 | ||||

| (SD = 20.61) | (SD = 7.86) | (SD = 0.35) | (SD = 0.32) | (SD = 322.92) | (SD = 249.73) | |||||

| 3 dB | 24.33% | 21.88% | 94.52% | 80.03% | 666.85 | 799.83 | ||||

| (SD = 11.70) | (SD = 11.88) | (SD = 0.08) | (SD = 0.27) | (SD = 132.65) | (SD = 232.93) | |||||

| 0 dB | 29.02% | 20.83% | 88.38% | 80.30% | 698.88 | 763.91 | ||||

| (SD = 23.75) | (SD = 12.83) | (SD = 0.096) | (SD = 0.25) | (SD = 147.828) | (SD = 250.97) | |||||

Repeated measure analysis of variance

The repeated measures analysis of variance was performed with DT (simple, moderate, and complex dual tasks) and noise (5 dB, 3 dB, and 0 dB SNR) as within-subject effects and group (Group 1: younger; Group 2: older) as a between-subject effect. There is a significant omnibus effect of DT [Wilks’ Lambda F(6,23) = 367.14, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.990]. There was no significant omnibus effect of noise or group. As a result of the small sample size, interaction effects were not explored. The effect of task on auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and visual reaction time will be explored next.

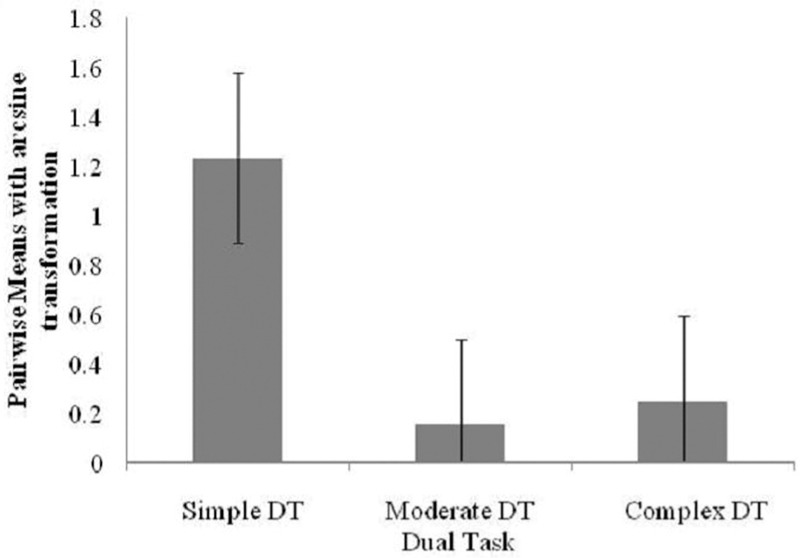

Auditory accuracy

A significant main effect of DT was found on auditory accuracy measures [F(1.71,47.81) = 963.15, P ≤ 0.001 η 2 = 0.972 (Greenhouse–Geisser Adjustment)]. To further examine this effect, a test of within-subject contrasts was conducted. Task was significant for auditory accuracy, with differences between simple DT and complex DT [F(1,28) = 1628, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.983], as well as moderate DT and complex DT [F(1,28) = 14.906, P = 0.001, η 2 = 0.347]. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections confirm that participants were more accurate during the simple DT (M = 1.23) and moderate DT (M = 0.153) tasks compared to the complex DT (M = 0.246) condition. Refer Figure 1 for details. Figure 1 includes transformed data, not percentage data.

Figure 1.

Pairwise means in auditory accuracy task performance. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

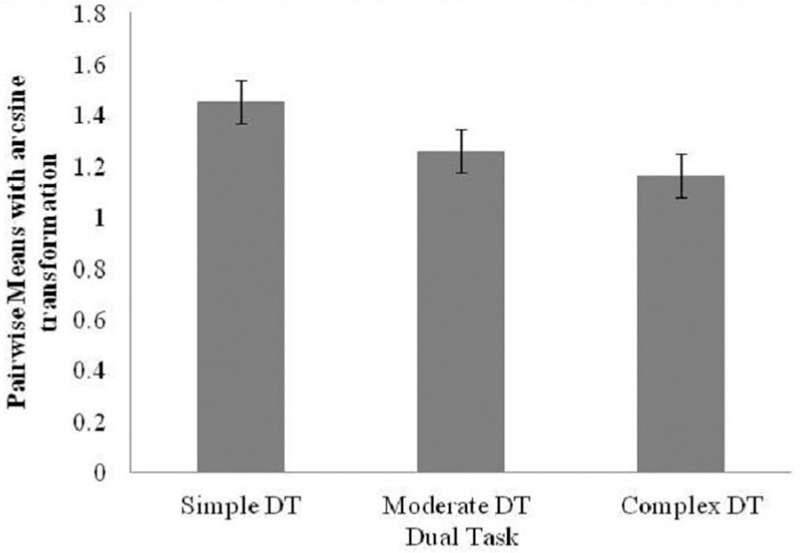

Visual accuracy

A significant main effect of DT was found on visual accuracy [F(1.91,53.46) = 15.23, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.352 (Greenhouse–Geisser Adjustment)], with the within-subject contrast revealing differences between simple DT and complex DT [F(1,28) = 28.94, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.508], as well as moderate DT and complex DT [F(1,28) = 5.01, P ≤ 0.033, η 2 = 0.152]. Using pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, it was found that the pairwise comparisons for visual accuracy were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Results suggest that in the simple DT (M = 1.45) and moderate DT (M = 1.26) levels, participants were more accurate than in the complex DT (M = 1.16) levels. Refer Figure 2 for details. Figure 2 includes transformed data, not percentage data. These findings indicate that simple DT was significantly different from both moderate DT and complex DT.

Figure 2.

Pairwise means in visual accuracy for task performance. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

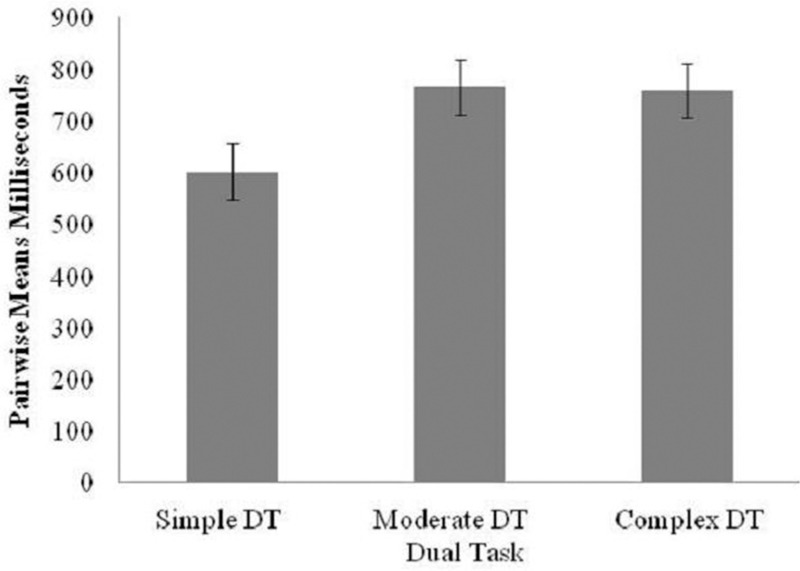

Visual processing speed

Finally, a significant main effect of task was found on visual processing speed [F(1.83,50.14) = 348.48, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.926 (Greenhouse–Geisser Adjustment)]. The within-subject contrast revealed that differences between simple DT and complex DT [F(1,28) = 515.32, P ≤ 0.001, η 2 = 0.948] were statistically significant. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections indicated that the simple task was significantly different from the complex tasks. However, the visual processing speed for the moderate task was not significantly different from the complex task. These differences suggest that for the simple DT participants were faster (M = 600) than at the moderate DT (M = 765.94) and the complex DT (M = 758.50) levels. Refer Figure 3 for details.

Figure 3.

Pairwise means in visual processing speed for task performance. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

Multivariate linear regression analysis

A multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to explore whether performance during participation in complex tasks (auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and visual reaction time) can be predicted from cognitive function as measured by the subtests of the WCJ-III test (Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, Visual Matching, and Decision Speed). The Memory for Words subtest predicted moderate DT auditory accuracy performance, with F(1,24) = 5.218, P = 0.031, R 2 = 0.216, only, suggesting that the more accurate the performance in Memory for Words, the greater auditory accuracy during the moderate dual-task condition. The Auditory Working Memory subtest predicted complex DT auditory accuracy performance [F(1,24) = 5.051, P = 0.034, R 2 = 0.549], indicating that increased Auditory Working Memory performance results in more accurate auditory accuracy in the complex dual-task condition. The Decision Speed subtest predicted simple DT visual accuracy performance [F(1,24) = 7.485, P = 0.012, R 2 = 0.420] and complex DT visual accuracy performance [F(1,24) = 4.272, P = 0.050, R 2 = 0.328], suggesting that as Decision Speed gets faster, visual accuracy increases in the simple and complex visual tasks. Decision Speed also negatively predicted complex DT visual reaction time performance [F(1,24) = 6.156, P = 0.020, R 2 = 0.376], indicating that as Decision Speed score increases, visual reaction time decreases. Thus, participants who completed more items tended to also score higher on complex visual reaction time tasks. Finally, the Visual Matching subtest predicted simple DT auditory accuracy performance [F(1,24) = 6.511, P = 0.018, R 2 = 0.236]. In summary, the following subtests of the WCJ-III test, Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, and Visual Matching all predicted auditory accuracy performance; however, the Auditory Working Memory subtests was the strongest predictor of auditory accuracy, yielding the larger R 2 = 0.549 at the complex dual task. Further, Decision Speed predicted performance for both visual accuracy and visual reaction time, but inconsistently across task complexity.

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate whether task complexity affects cognitive load and if cognitive function subtests may predict performance during complex tasks. We first discuss the results of the group data followed by the regression findings. The results of the group analysis suggest that task complexity has a significant effect on auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and visual processing speed, indicating that listening effort or cognitive load was successfully manipulated by the different levels of task. In general, auditory and visual accuracy decreased and reaction time increased with increased task complexity, suggesting increased cognitive load across tasks. During the simple dual task, auditory accuracy was not negatively affected. However, as task complexity increased, auditory accuracy decreased significantly.

This suggests that a more challenging primary task is necessary to elucidate which cognitive factors are important in explaining individual differences in auditory accuracy.

Task complexity had a more predictable effect on visual accuracy, because visual accuracy decreased with each increase in complexity. Additionally, task complexity also significantly affected visual processing speed, showing that as task complexity increased, processing speed decreased. The investigation of dual-task performance is important for the study of listening effort across age groups and cognitive skill.[11,14] The results of this study highlight the fact that task complexity or difficulty significantly affects the results of dual-task methodologies in listeners with normal cognitive screening results and near-normal hearing. Additionally, a simple dual task may not show cognitive loading if it does not challenge the listener significantly, and, subsequently, performance may be overestimated. By including more challenging dual tasks, investigators may begin to see the level of complexity at which performance may start to break down, thus providing a deeper understanding of function during more challenging tasks. These findings support previous literature that show that listening effort is increased in DTPs and contributes to the understanding of cognitive function across task complexity. On the basis of these findings, cognitive processing breakdown occurs between simple dual-task condition and the moderate and/or complex dual-task conditions.

Unexpectedly, the analysis of the group data did not reveal an effect of age on cognitive load. This is surprising because previous research[1,5,20,31] has found that older listeners show increased listening effort compared to younger listeners. However, in many of these studies, the younger listeners are often college-aged students (18–25 years old), increasing the likelihood of finding an age effect.[12] In the current study, listeners in the young group (Group 1) ranged in age from 41 to 61 years, whereas the older listeners were from 63 to 81. This covers a smaller range of age and leaves a smaller age gap between groups compared to other studies.[1,5,31] The reason for the different age selection here was to maximize variation in cognitive function within the normal range for older adults. However, Degeest et al.[20] did find an effect of age with a similar separation between age groups. Zekveld et al.[17] have discussed this limitation for a similar subject design for a speech-perception-in-noise pupil-dilation study in older and middle-aged adults. As a result of the continued change of cognition and neurocognitive processes with age, appropriate age selection criteria are unclear. Choosing a larger age separation and including a young adult age group may have revealed a significant age effect. Regardless, age effects likely include a strong cognitive component, as discussed in the following section. Second, all of the participants included in this study demonstrated normal cognition within the cognitive skills contributing to listening effort. Of the studies that have shown an effect of age on cognitive load, some have used cognitive screens only for the older participants,[20] and others have used abbreviated cognitive screens that may not have been sensitive to listening effort.[1,20] Thus, it is unclear whether age differences found in some of the studies may be due to a lack of sensitivity of cognitive screening protocol, thereby potentially including some participants with possible cognitive decline in the older group. Furthermore, including much younger participants as the control group may conflate age with changes in hearing.A second goal of the current study was to explore whether performance on the dual tasks could be predicted from the WCJ-III battery. The current results suggest that the WCJ-III test of cognitive abilities subtests Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, Visual Matching, and Decision Speed each predict performance on dual tasks, regardless of age. Specifically, each of the subtests predicts different levels of dual-task performance across task complexity. Auditory accuracy, across all levels of DT, was predicted by Memory for Words, Auditory Working Memory, and Visual Matching. Further, Decision Speed predicted visual accuracy performance at the simple DT level and visual reaction time in both the simple and complex DT levels. These results suggest that examining participant cognitive function across working memory and processing speed may predict performance across dual tasks of varying complexity. Because we only included participants who had normal cognitive function, the relationship between these variables may become stronger as participants with declining cognitive function are included.

The dual-task hierarchy we designed for this study warrants review. While the purpose of the current study was to investigate a possible predictive relationship cognitive function and dual-task performance, the use of dual-task methodology remains highly variable across fields and merits further exploration. The current study included recall of words in isolation part of the moderate DT, with recall of words in a sentence part of the complex DT. We reasoned that recall of words in a sentence would be more difficult than recall of words in isolation, because cognitive processing of sentences may require additional resources. However, our results indicate that the recall of words in isolation may be more challenging in sentence context, because no sentence context was used to guide perception. Further investigation of more challenging levels of dual-task hierarchy may inform researchers and clinicians regarding multitasking performance during tasks of everyday life across varying populations and age groups. In additional to dual-task hierarchy, further investigation with a larger sample size is warranted. Despite the small sample size, which limits statistical power, significant prediction of dual-task performance was found, which addresses the aim of the study.

Implications of results

As our understanding of the relationship between cognition and listening effort improves, it becomes increasingly apparent that an audiological test battery may need to include a cognitive screening to better understand daily function. This study identifies four cognitive subtests which, in combination, significantly predict auditory accuracy, visual accuracy, and visual reaction time during dual-task performance of varying complexity. These findings may inform both researchers and clinicians regarding the relationship between cognitive screens and listening effort when working with individuals during complex speech recognition in noise tasks. Further, this finding highlights that collaborative relationships between speech-language pathologist and audiologist are likely needed to better understand the communicative capacity of participants.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gosselin PA, Gagné JP. Older adults expend more listening effort than younger adults recognizing speech in noise. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54:944–58. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0069). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser S, Gagné JP. Evaluating the effort expended to understand speech in noise using a dual task paradigm: The effects of providing visual speech cues. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010;53:18–33. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0140). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichora-Fuller MK. How cognition might influence hearing aid-design, fitting, and outcomes. Hear J. 2009;62:32, 34, 36, 38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarampalis A, Kalluri S, Edwards B, Hafter E. Objective measures of listening effort: Effects of background noise and noise reduction. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52:1230–40. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0111). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tun PA, McCoy S, Wingfield A. Aging, hearing acuity, and the attentional costs of effortful listening. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:761–6. doi: 10.1037/a0014802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akeryod MA. Are individual differences in speech reception related to individual differences in cognitive ability? A survey of twenty experimental studies with normal and hearing-impaired adults. Int J Audiol. 2008;(Suppl 2):S53–71. doi: 10.1080/14992020802301142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCoy SL, Tun PA, Cox LC, Colangelo M, Stewart RA, Wingfield A. Hearing loss and perceptual effort: Downstream effects on older adults’ memory for speech. Q J Exp Psychol. 2005;58:22–33. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pichora-Fuller MK, Schneider BA, Daneman M. How young and old adults listen to and remember speech in noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97:593–608. doi: 10.1121/1.412282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salthouse T. When does age-related cognitive decline begin. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downs DW. Effects of hearing aid use on speech discrimination and listening effort. J Speech Hear Disord. 1982;47:189–93. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4702.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosselin P, Gagné JP. Use of dual task paradigm to measure listening effort. Can J Speech Lang Pathol Audiol. 2010;34:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desjardins JL, Doherty KA. The effect of hearing aid noise reduction on listening effort in hearing-impaired adults. Ear Hear. 2014;35:600–10. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holtzer R, Stern Y, Rakit B. Predicting age-related dual-task effects with individual differences on neuropsychological tests. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:18–27. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picou EM, Ricketts TA. The effect of changing the secondary task in dual-task paradigms for measuring listening effort. Ear Hear. 2014;35:611–22. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picou EM, Ricketts TA, Hornsby BW. Visual cues and listening effort: Individual variability. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54:1416–30. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0154). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudner M, Lunner T, Behrens T, Sundewall-Thoren E, Ronnberg J. Working memory capacity may influence perceived effort during aided speech recognition in noise. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23:577–89. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.7.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, Festen JM. Cognitive load during speech perception in noise: The influence of age, hearing loss, and cognition on the pupil response. Ear Hear. 2011;32:498–510. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31820512bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zekveld AA, Festen JM, Kramer SE. Task difficulty differentially affects two measures of processing load: The pupil response during sentence processing and delayed cued recall of the sentences. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2013;56:1156–65. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0058). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montréal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degeest S, Keppler H, Corthals P. The effect of age on listening effort. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2015;58:1592–600. doi: 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-H-14-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, Glymour MM, Elbaz A, Berr C, Ebmeier KP, et al. Timing of onset of cognitive decline: Results from Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodcock RW, Mather N, McGrew KS. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities – Examiner’s Manual. Itasca: Riverside; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrank FA, Wendling BJ. Educational interventions and accommodations related to the Woodcock-Johnson® III Tests of Cognitive Abilities and the Woodcock-Johnson III Diagnostic Supplement to the Tests of Cognitive Abilities (Woodcock-Johnson III Assessment Service Bulletin No. 10) Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologica. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornsby BW. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained processing demands. Ear Hear. 2013;34:523–34. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828003d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilger RC, Neutzel JM, Rabinowitz WM, Rzeczkowski C. Standardization of a test of speech perception in noise. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1984;27:32–48. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2701.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalikow DN, Stevens KN, Elliott LL. Development of a test of speech intelligibility in noise using sentence materials with controlled word predictability. J Acoust Soc Am. 1977;61:1337–51. doi: 10.1121/1.381436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsh IJ. The Measurement of Hearing. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cedrus Corporation. SuperLab (Version 4.5) [Computer Software] United States: Cedrus Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1980;19:450–66. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desjardins JL, Doherty KA. Age-related changes in listening effort for various types of masker noises. Ear Hear. 2013;34:261–72. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826d0ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]