Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of 0.1% curcumin mouthwash and to compare it with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate as an antiplaque agent and its effect on gingival inflammation.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and fifty subjects, age between 20 and 30 years were recruited. Study population were randomly divided into three groups. In Group A, 50 subjects were advised the experimental mouthwash. Group B subjects used placebo mouthrinse, and chlorhexidine mouth wash was given to Group C. The subjects were advised to use 10 ml of mouthwash for 1 min twice a day 30 min after brushing. Parameters were recorded for plaque, gingival, and sulcus bleeding indices at day 0, 7, 14, and 28 days along with subjective assessment of taste.

Results:

On intragroup comparison between curcumin, chlorhexidine, and placebo mouthwash, the mean percentage reduction of the plaque index (PI) between 0 and 28 days were 0.58,0.57 and 1.17, respectively (P < 0.01), percentage reduction of gingival index (GI) between 0 and 28 days were 0.65, 0.66, and 1.09, respectively (P < 0.01) and sulcus bleeding index (SBI) showed a percentage reduction of 0.69, 0.66, and 1.13, respectively The intergroup comparison revealed chlorhexidine and curcumin mouthwash were statistically significant with P < 0.001 as compared to placebo.

Conclusion:

Curcumin mouthwash has shown an antiplaque and antigingivitis properties comparable to chlorhexidine mouthwash. Thus, curcumin mouthwash and chlorhexidine gluconate can be effectively used as an adjunct to scaling and root planning.

Key words: Curcumin mouthwash, chlorhexidine mouthwash, gingivitis

INTRODUCTION

The oral cavity approaching the time of birth starts getting colonized by various nature of microbiota. Among the lot, few microbiota eventually can adhere to the host forming dental plaque leading to the induction of infectious diseases such as gingivitis and periodontal disease. The dental plaque is considered the sole prominent factor for initiation and progression of periodontal disease.[1]

Plaque control can be advocated by means of mechanical (brushes, floss, and interdental aids) and chemical means. Along with mechanical mode of plaque control, chemical plaque control too has gained popularity due to its unique characteristics.

In the field of dentistry, the most popularly rewarded chemical means of maintaining a good oral hygiene has been gained by chlorhexidine. It is considered the gold standard due to its diverse properties. The antimicrobial and antiplaque activity of it brings the best bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity.[2] However, it too has shown certain side effects such as brown discoloration of the teeth, oral mucosal erosion, and bitter taste.[3]

Ayurveda system of medicine has its root in Indian subcontinent which is being globalized and practices as alternative medicine in the Western world. It is typically based on complex herbal compounds, minerals, and metal substances.[4] Curcumin was primarily isolated by Vogel (1842); it is a bright yellow spice, obtained from the rhizome of Curcuma longa Linn plant. The structure of circumin was characterized by Milbedzkar et al., in the year 1910[5] and was synthesized in 1913 by Lampe et al.[5] The usage of Curcumin has a long history from the time China, India, and Iran used it as traditional medicine, and it has been used in various forms for the treatment of many diseases such as diabetes, liver disease, rheumatoid diseases, atherosclerosis, infectious diseases, and cancers.[6] Various formulations of curcumin in the form of powder, paste, gel, and poultice has been extensively used proving its various pleiotropic effect. It is known for its formidable effect as an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, along with its hepatoprotective, immunostimulant, antiseptic, and antimutagenic properties.[7]

Therefore, the present study reckoned the effect of antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of curcumin and chlorhexidine mouthwash in moderate-to-severe gingivitis subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The research was conducted in the Department of Periodontics, Oxford Dental College, Bengaluru, where 150 subjects were recruited. The subjects were recruited based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria included subjects of age group of 20–40, with minimum 20 permanent erupted teeth, mild-to-moderate gingivitis with gingival index (GI) score less than ≥1 score,[8] plaque score ≥1 as per plaque index (PI) score,[9] no history of previous periodontal surgery, and systemically healthy subjects. The subjects known allergic to curcumin, with discharge of pus, involvement of the root furcation and deeper pocketing, had oral prophylaxis and antibiotic therapy in the past 6 months, breathing habits, smoking, and subjects with orthodontic and prosthetic appliances, pregnant and lactating mothers were excluded from the clinical trial.

Study design and clinical parameters

The study design was double-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial in which 150 subjects fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly divided into Group A, B, and C.

The randomization was performed with randomization software (http://www.randomization.com/)

Group A: Experimental mouthwash (curcumin mouthwash)

Group B: Placebo

Group C: Control (chlorhexidine mouthwash) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Formulation A: Experimental (curcumin) mouthwash (Group A), formulation B: placebo mouthwash (Group B), formulation C: Chlorhexidine mouthwash (Group C)

The preparation of experimental (curcumin) mouthwash and placebo mouthwash was carried out by Sanso Syre pharmaceutical company. The main ingredient used in the formulation was Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), a polyphenol derived from C. longa plant, which comprises 0.3%–5.4% of raw turmeric. The flavonoid curcumin (diferuloylmethane) and volatile oils including tumerone, atlantone, and zingiberone are the various active constituents of turmeric. Other constituents include sugars, proteins, and resins. The placebo mouthwash contained saline which was used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP).

The Group B mouth wash used was a placebo group which consisted of 2 g of coconut oil, 1 g of mint, 15 g of propylene glycol, tween 60 of 20 g, and distilled water.

The Group C mouthwash used in the clinical trial was chlorhexidine mouthwash at a concentration of 0.2% which is considered the gold standard in the chemical plaque control measures.

Informed consent was obtained from the participating subjects. At baseline, the subjects were assessed for PI,[9] GI,[8] and sulcus bleeding index (SBI).[10] Following the recordings of clinical parameters, SRP were performed. Oral hygiene instructions along with the usage of designated mouthwash were advised to the respective groups.

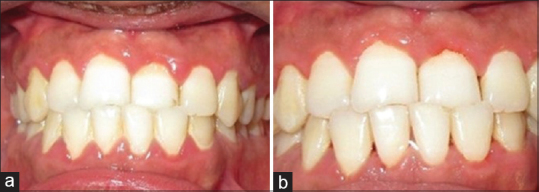

The clinical trial was conducted for 28 days. The patients were instructed to follow the mouthwash usage as per the instruction and advised to rinse for 1 min twice a day after 30 minutes of tooth brushing. The clinical parameters were recorded again at 7 days, 14 days and 28 days. Figures 2–4 illustrates the baseline and 28th day follow up period in Group A, B and C respectively.

Figure 2.

Group A: Baseline (a) and 28th day (b)

Figure 4.

Group C: Baseline (a) and 28th day (b)

Figure 3.

Group B: Baseline (a) and 28th day (b)

The subjective criteria included the taste acceptability which was graded as acceptable, tolerable, and unacceptable based on a questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analysis was done using SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago, IL, USA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Intergroup analysis of clinical parameters between the Group A, B, and C was done with ANOVA test. Intragroup analysis was performed by repeated ANOVA test. The subjective criteria for taste acceptability were calculated with Fisher's extract test.

RESULTS

A total of 150 subjects were statistically evaluated after the periodic recall visits for the present study.

At baseline Group A (Curcumin), Group B (placebo), and Group C (Chlorhexidine) did not show any significant statistical difference in respect PI, GI, SBI).

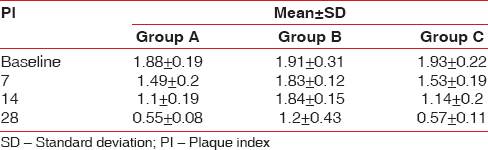

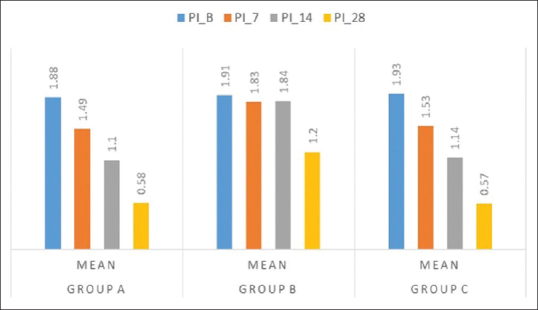

Plaque index

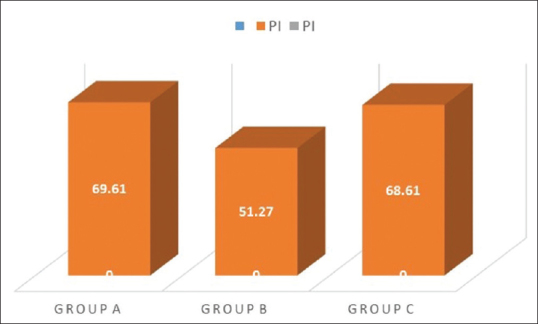

The PI reduced during the study period in all the three groups, and statistical significant difference was obtained in Group A and Group C as observed in [Table 1 and Figure 5]. On comparison between Group A, Group B, and Group C, a statistical significant reduction in PI was observed in curcumin and chlorhexidine mouthwash as compared to placebo where the percentage reduction of PI for the 3 groups showed 68.61 ± 7.18, 51.27 ± 13.21, and 69.81 ± 7.49, respectively. The mean percentage reduction in PI was statistically significant in Group A and Group C as compared to Group B. The PI % score was statistically significant in Group A as compared to placebo and control mouthwash [Figure 6 and as tabulated in Table 2].

Table 1.

The intergroup comparison of plaque index at various interval

Figure 5.

Intergroup comparison of mean plaque index at various interval period

Figure 6.

Plaque index percentage score mean of Group A, B, and C

Table 2.

Percentage reduction of plaque index in Groups A, B and C

Group A: The mean PI was 1.88 ± 0.19 on day 0 and 0.58 ± 0.11 at 28th day follow-up period showing statistically significant difference with P < 0.001

Group B: The PI at day 0 was 1.95 ± 0.23 which reduced to 1.17 ± 0.43 at 28 days follow-up period which was statistically not statistically significant

Group C: The mean PI at baseline was 1.93 ± 0.22 which reduced to 0.57 ± 0.11 at 28 days follow-up period (statistically significant P < 0.001).

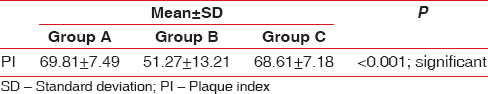

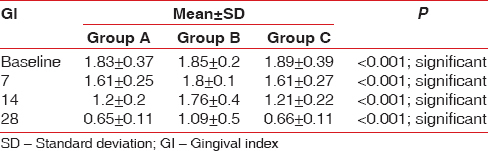

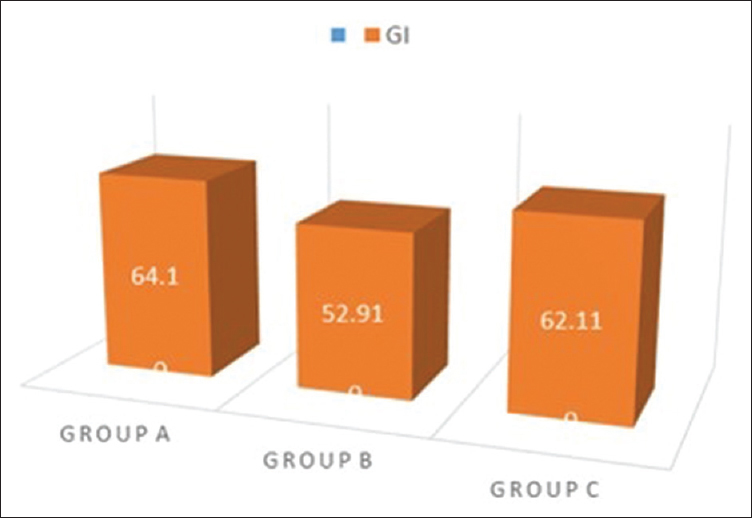

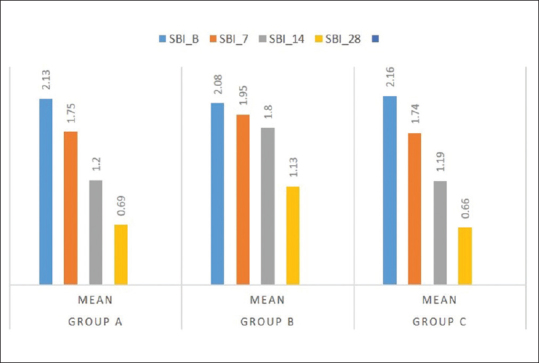

Gingival index

The GI score showed a satisfying decrease in the groups clinically, and statistical significant difference was obtained in Group A and Group C as compared to Group B [Table 3 and Figure 7]. Comparing the percentage reduction of GI in the three groups, Group A and Group C have statistically significant difference with mean values of 68.6 ± 7.18 and 69.81 ± 7.49, respectively. The GI percentage score was statistically significant in Group A and Group C as compared to Group B [Figure 8 and Table 4].

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of gingival index at baseline, 7, 14, and 28 days in Groups A, B, and C

Figure 7.

Mean gingival index values at various interval for Group A, B, and C

Figure 8.

Gingival index percentage score seen in Group A, B, and C

Table 4.

Percentage reduction in gingival index

Group A: The mean GI at baseline and 28th day follow-up showed a statistical significant difference with values of 1.83 ± 0.37 and. 65 ± 0.11, respectively

Group B: The difference in mean at day 0 and 14th follow-up period showed 1.95 ± 0.42 and 1.09 ± 0.47, respectively, showing no significant difference in the intragroup comparison

Group C: At day 0, the mean GI was 1.89 ± 0.39, and at 28th day follow-up period, it showed 66 ± 0.11 showing a statistically significant difference with P < 0.01.

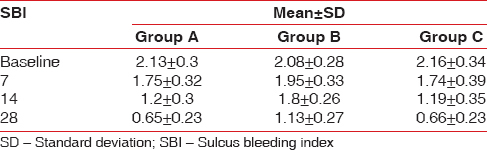

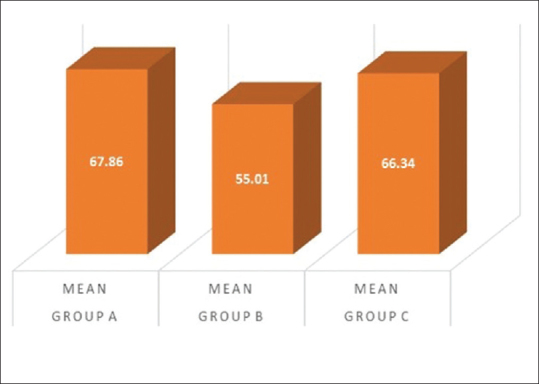

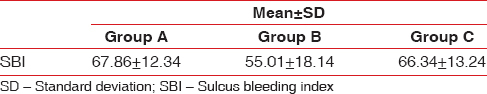

Sulcus bleeding index

The SBI score showed a satisfying decrease in the groups clinically, and statistical significant difference was obtained in Group A and Group C as summarized in [Table 5 and Figure 9]. Comparing the percentage reduction of SBI in the three groups, Group A and Group C have statistically significant difference with mean values of 66.34 ± 12.92and 67.86 ± 13.17, respectively, as summarized in Figure 10 and as tabulated in Table 6.

Table 5.

Intergroup analysis of sulcus bleeding index at periodic recall interval

Figure 9.

At various follow-up period, the mean sulcus bleeding index scores in Group A, B, and C

Figure 10.

Percentage reduction of sulcus bleeding index in Group A, B, and C

Table 6.

Percentage reduction in sulcus bleeding index

Group A - The mean SBI at baseline and 28th day follow-up showed a significant statistical difference with values of 2.13 ± 0.30 and. 66 ± 0.23, respectively

Group B - The difference in mean at day 0 and 14th follow-up period showed 2.08 ± 0.28 and 1.13 ± 0.27, respectively, showing no significant difference in the intragroup comparison

Group C - At day 0, the mean SBI was 2.16 ± 0.34, and at 28th day follow-up period, it showed 0.66 ± 0.23 showing a statistically significant difference with P < 0.01.

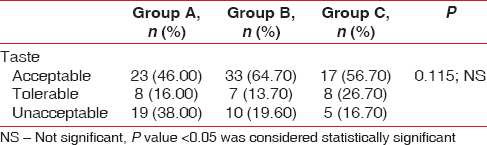

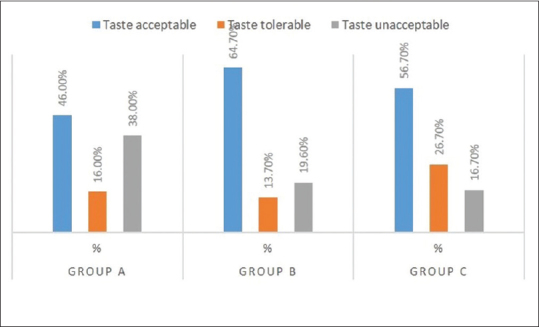

Subjective criteria

When the taste perception of the mouthwash was evaluated, the Group A mouthwash has unacceptable taste of 38%, as compared to Group B and C which showed unacceptable test of 19.65 and 16.7%. However, the data obtained were notstatistically significant as observed in Table 7 and Figure 11.

Table 7.

Percentage of taste perception in Groups A, B, and C

Figure 11.

Mean scores of subjective criteria (taste perception) in Group A, B, and C

DISCUSSION

The consideration of the present clinical trial was to evaluate the antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of an herbal mouthwash (curcumin) with the most established chlorhexidine mouthwash which was considered the gold standard in the field of chemical plaque control. The subjects recruited were compliant and met the follow-up visits after a single setting of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. A clinically significant reduction was seen in experimental (curcumin) group and control (chlorhexidine) group as compared to placebo in moderate-to-severe gingivitis.

Curcumin has plethora of activities including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant agent. The lipophilic nature of the molecule allows rapid permeability of cell membrane. The PI in the Group A and Group C was comparable from Group C. The reduction in the plaque level at 28th day follow-up period could be attributed to bactericidal property of the herbal product. The curcumin mimics various events that happen during apoptosis process by causing change in the function and structure of cell membrane.[11]

The GI score and sulcus bleeding index score of both curcumin and chlorhexidine showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline to 14 and 28 days. This result of the experimental mouthwash group could be best explained by its anti-inflammatory property, which inhibits tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-dependent NF-B activation, reducing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).[12] The curcumin is also known to be immune modulating agents which downregulates the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme and inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory enzyme. Downregulation of various inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, interferon, and some other chemokines are also carried by the circumin.[13] Considering the anti-inflammatory effect of turmeric and chlorhexidine mouthwash, the results of the present study were consistent with the results of Waghmare et al.,[14] Van der Weijden et al.,[15] Grundemann et al.,[16] and Leyes, et al.[17] The progression of disease progression was markedly reduced by the activity of curcumin as pro-oxidant and antioxidant by scavenging the free radical, a reducing agent and a DNA damage inhibitor.[18] The curcumin inhibits ROS and nitric oxide (NO) production in macrophages.[19,20] A study done by Mali et al. evaluating turmeric mouthwash with chlorhexidine showed a considerable decrease in plaque and gingival score which was further emphasized with the use of microbiological testing showing a reduction in supragingival microbial load.[21] Muglikar et al. in 2013 evaluated 30 subjects for 21 days and observed that circumin mouthwash was comparable to chlorhexidine mouth wash as a potent anti-inflammatory agent.[22]

The curcumin mouthwash was biocompatible to oral tissues and was acceptable in taste. Observation from the present study from subjective criteria stated that bitter taste was experienced by few subjects using curcumin mouthwash but was not statistically significant when compared to the gold standard chlorhexidine mouthwash. No side effects were reported by the subjects in using the three mouthwash during the study. Group C showed a mild stain formation on the lingual surface of mandibular anterior segment by few of the subjects.

Although multiple pharmacological effects of curcumin have showed a wide variety of activities, it has been found to be quite safe in both animals and humans. Fewer research with different concentrations of circumin has been evaluated for short-term and long-term Toxicity. The doses evaluated were at 50, 250, 480, 1300 for periods of 13 weeks or 2 years in rats and mice where side effects such as increase in liver weight, discoloration of face and when received at a dose of 2600 mg/kg showed mucosal epithelium hyperplasia in the cecum and colon of animals but were considered as relative toxicity.

However, considering the recent outlook, the Food and Drug Administration has declared curcumin as “generally safe.”

Standardizing the dose of curcumin and the formulation is known to have a wide array of usage in the field of periodontology and can be compared to the gold standard chemical plaque control due to its diverse property as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal therapy.

CONCLUSION

Thus, the results obtained from the present clinical trial, proves the antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of curcumin mouthwash. It could, therefore, be used as an adjunct to mechanical therapy and is comparable with the usage of chlorhexidine mouthwash.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 11th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012. p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones CG. Chlorhexidine: Is it still the gold standard? Periodontol. 2000;1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang NP, Jan L. London, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard; 6th ed. London, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2015. Textbook of Clinical Periodontology and Implantology Dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milobedzka J, Kostanecki S, Lampe V. Curcumin. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1910;43:2163–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammon HP, Wahl MA. Pharmacology of curcuma longa. Planta Med. 1991;57:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilak JC, Banerjee M, Mohan H, Devasagayam TP. Antioxidant availability of turmeric in relation to its medicinal and culinary uses. Phytother Res. 2004;18:798–804. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noorafshan A, Ashkani-Esfahani S. A review of therapeutic effects of curcumin. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:2032–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mühlemann HR. Psychological and chemical mediators of gingival health. J Prev Dent. 1977;4:6–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaruga E, Salvioli S, Dobrucki J, Chrul S, Bandorowicz-Pikuła J, Sikora E, et al. Apoptosis-like, reversible changes in plasma membrane asymmetry and permeability, and transient modifications in mitochondrial membrane potential induced by curcumin in rat thymocytes. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:287–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amit S, Ben-Neriah Y. NF-kappaB activation in cancer: A challenge for ubiquitination-and proteasome-based therapeutic approach. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Kuo J, Jiang H, Deeb D, Liu Y, Divine G, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of curcumin: Suppression of lymphocyte proliferation, development of cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and cytokine production in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waghmare PF, Chaudhari AU, Karhadkar VM, Jamkhande AS. Comparative evaluation of turmeric and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in prevention of plaque formation and gingivitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:221–4. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Weijden GA, Timmer CJ, Timmerman MF, Reijerse E, Mantel MS, van der Velden U, et al. The effect of herbal extracts in an experimental mouthrinse on established plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antunes LM, Araujo MC, Da Luz Dias F, Takahashi CS. Effects of H2O2, Fe2+and Fe3+on curcumin-induced chromosomal aberrations in CHO cells. Genet Mol Biol. 2005;28:161–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gründemann LJ, Timmerman MF, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Reduction of stain, plaque and gingivitis by mouth rinsing with chlorhexidine and peroxyborate. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2002;109:255–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyes Borrajo JL, Garcia VL, Lopez CG, Rodriguez-Nuñez I, Garcia FM, Gallas TM, et al. Efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthrinses with and without alcohol: A clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:317–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ak T, Gülçin I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;174:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreejayan, Rao MN. Nitric oxide scavenging by curcuminoids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:105–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mali AM, Behal R, Gilda SS. Comparative evaluation of 0.1% turmeric mouthwash with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate in prevention of plaque and gingivitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:386–91. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.100917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muglikar S, Patil KC, Shivswami S, Hegde R. Efficacy of curcumin in the treatment of chronic gingivitis: A pilot study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:81–6. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]