Abstract

Background:

Periodontal disease prevalence in children is an indicator of future disease burden in the adult population. Knowledge about the prevalence and risk status of periodontal disease in children can prove instrumental in the initiation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic measures.

Aim:

This school-based cross-sectional survey estimated the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease among 15–17-year-old children in Kozhikode district and assessed the risk factors.

Materials and Methods:

Multistage stratified random sampling and randomized cluster sampling were used in the selection of schools and study participants, respectively, in three educational districts of Kozhikode. Periodontal disease was assessed among 2000 school children aged 15–17 years, by community periodontal index. A content validated questionnaire was used to evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics and other risk factors.

Results:

The prevalence of periodontal disease was estimated as 75% (72% gingivitis and 3% mild periodontitis). The prevalence was higher in urban population (P = 0.049) and males had significantly (P = 0.001) higher prevalence. Lower socioeconomic strata experienced slightly more periodontal disease burden. Satisfactory oral hygiene practices (material and frequency) were observed, but oral hygiene techniques were erroneous. Unhealthy dental treatment-seeking practices and unfavorable attitude toward dental treatment (ATDT) significantly influenced periodontal health status. Overall awareness about dental treatment was poor in this study population.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of periodontal disease among 15–17-year-old school children in Kozhikode district is 75% and is influenced by sociodemographic characteristics. Other risk factors identified were unhealthy dental treatment-seeking practices and unfavorable ATDT. Implementation of well-formulated oral health education programs is thus mandatory.

Key words: Adolescent, community periodontal index, gingivitis, periodontal disease, periodontitis, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is one of the most common oral diseases affecting humankind from time immemorial. The different forms of periodontal disease which can affect children and adolescents include gingivitis, periodontitis, etc.[1] The prevalence and severity of periodontal disease depend not only on the local factors but also on various modifiable risk factors. The behavioral risk factors such as dental health awareness, attitude, and dental health-care seeking practices of the individual may play a crucial role in the periodontal disease burden of the population.

An epidemiological study reported a low prevalence of gingivitis during preschool age, followed by a gradual increase, and reaching a peak around puberty.[2] Puberty gingivitis is due to increased inflammatory gingival response which may be caused by plaque bacteria, the inflammatory response and hormonal changes, other local factors such as malocclusion, functional habits, and dietary habits.[3]

Dental plaque biofilm is the principal etiological factor in the development of puberty gingivitis. Several studies have demonstrated that regular removal of dental plaque can prevent the occurrence and progression of early periodontal disease.[4,5,6] Adolescence is a period, whereby an individual develops behavioral patterns that might persist into adulthood.[7] Regular dental checkups, good awareness about dental health maintenance, good dental health-care seeking practices, and a favorable attitude toward dental specialist and dental treatment is thus imperative for optimal oral health.

The prevalence of periodontal disease above the age of 35 years is reported to be 78.6% in Kerala population as per the National Oral Health Survey conducted by Dental Council of India in 2003, in India.[8] Kozhikode is a socially and educationally forward district of the Kerala state. There is no authoritative data or studies, so far describing the distribution of periodontal disease among school children in Kozhikode district. Knowledge about the prevalence and risk status of periodontal disease in children can prove instrumental in the initiation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic measures. Hence, this study was undertaken to estimate the prevalence of periodontal disease among the 15–17-year-old school children in Kozhikode district and to assess the role of sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, location, and socioeconomic status) and other modifiable risk factors on the prevalence. The modifiable risk factors included the oral hygiene habits, the presence of personal habits and crowding, general awareness and attitude about dental health and treatment as well as their dental health-care seeking practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This school-based cross-sectional survey was conducted among children aged 15–17 years in Kozhikode district. Data collection was carried out by clinical examination and structured questionnaire. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC no: 48/2014/DCC dated 22/12/14). Kozhikode district is subdivided into 3 educational districts, namely, Kozhikode, Thamarassery, and Vadakara Educational District. This survey was conducted among government higher secondary schools located in the urban and rural areas of these three educational districts. Permissions were obtained from the District Educational Officers as well as the Principals of the selected schools. Informed consent and assent were obtained.

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated on the basis of a previous study[9] using the formula,

Where, Z α = 1.96, Z β = 0.84, P = prevalence (average of expected change in prevalence), q = 100 − p, d = effect size.

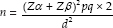

According to this, the sample size in each group (urban and rural) was calculated as 965 school children. A sample of 1000 students each was included in the urban and rural group, thus making the total sample size as 2000 students. A multistage stratified random sampling and randomized cluster sampling were done in the selection of schools and study participants, respectively [Figure 1]. All school children between 15 and 17 years of age with minimum of 20 teeth were included. The children whose parents had not given the informed consent and/or assent, uncooperative and medically compromised students were excluded from this study.

Figure 1.

Study design flow chart

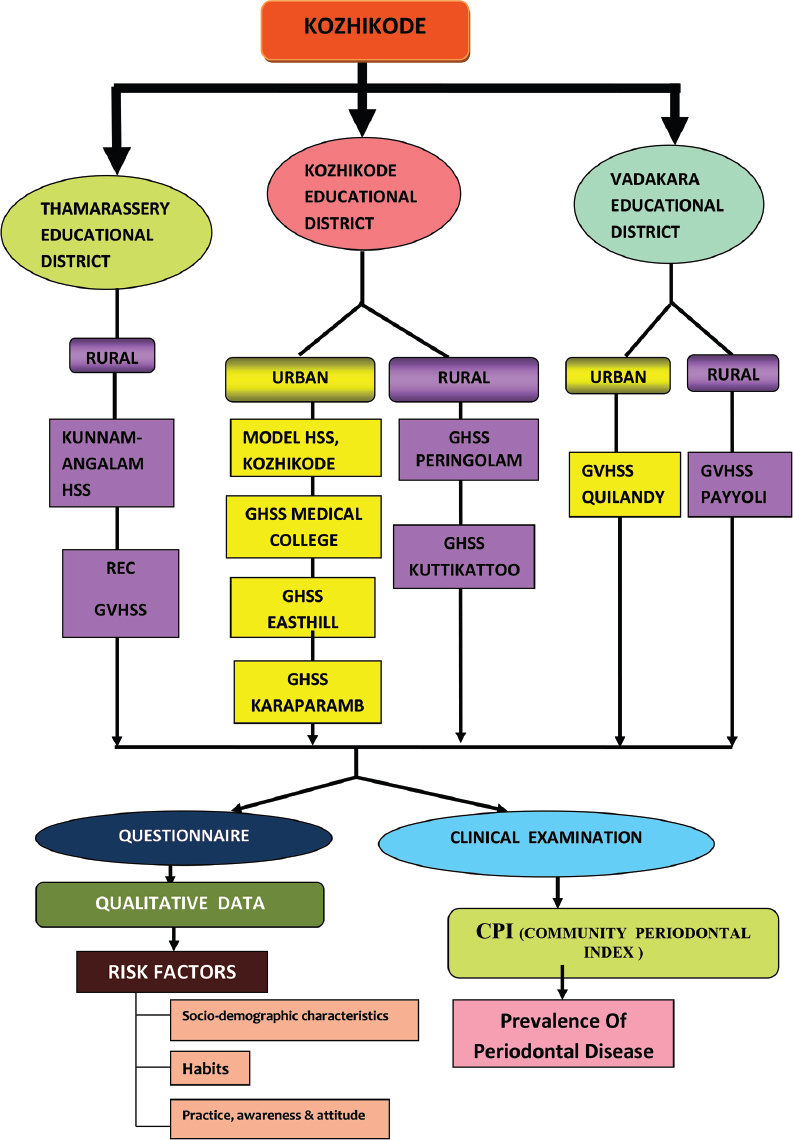

Periodontal status was assessed by community periodontal index (CPI). A content validated, structured questionnaire [Figure 2] was used for assessing the Dental Health Attitude. It comprises of dental treatment-seeking practices (DTSP), awareness about dental treatment (DA) and attitude toward dental treatment (ATDT). The socioeconomic status was assessed using the Kuppusamy's criteria for socioeconomic status assessment, 2014.[10]

Figure 2.

Dental health attitude questionnaire

The oral and periodontal examinations were conducted by a single calibrated examiner (UMD), using a standard mouth mirror and CPI probe. Distribution of study participants by their highest CPI Score was recorded, and the participants were further categorized as normal group (CPI code 0), gingivitis group (CPI code 1 and code 2), and periodontitis group (CPI Code 3) for the purpose of this study. The data were again classified as periodontally healthy (code 0) and periodontally diseased (code 1, code 2, and code3). DMFT index was also recorded.

For assessment of the DTSP, awareness about dental treatment (DA) and ATDT, a structured questionnaire was used after content validation. Each component was assessed using a questionnaire containing 5 questions. Scores were assigned to each response. Sum of each set of 5 questions was calculated and the median of the sum obtained. All values above the median were taken as favorable response (healthy practice, good awareness, and favorable attitude) while the median and values below it were considered as unfavorable response (unhealthy practice, poor awareness, and unfavorable attitude).

For statistical analysis, mean ± standard deviation [SD] was calculated for quantitative variables and frequency for qualitative variables. Frequency of the highest CPI score of each participant was calculated for the estimation of prevalence of periodontal disease. The prevalence was expressed in percentage. Chi-square test was used to compare sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors (oral hygiene practices and personal habits) between the periodontally healthy and diseased groups. Comparison of dental treatment seeking practice, awareness, and attitude scores among the different CPI score categories was performed using Chi-square test, and their association was assessed. DMFT was calculated as mean DMF ± SD.

RESULTS

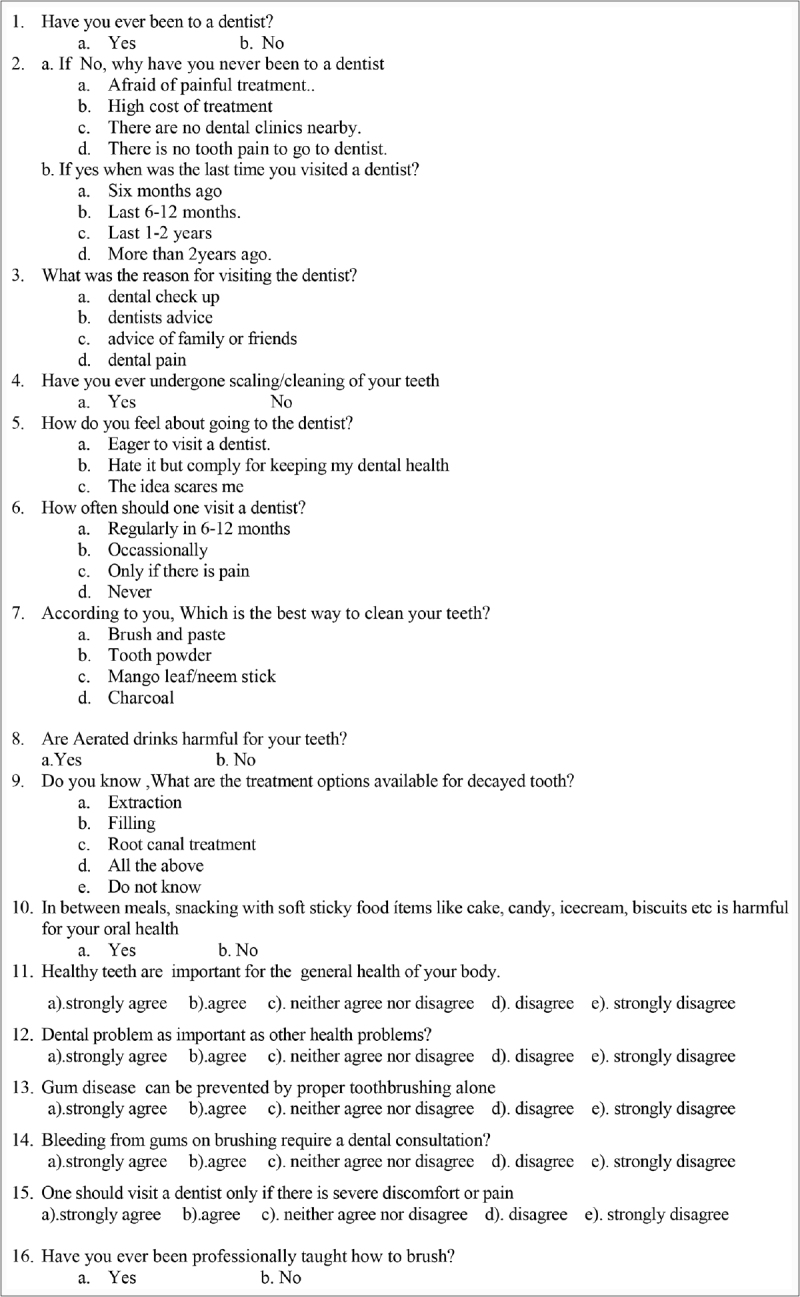

In this study, it was observed that 25% were periodontally healthy (Code 0), 20% had bleeding on probing (Code 1), 52% had calculus (Code 2), and 3% had mild periodontitis with probing pocket depth of 4–5 mm (Code 3 with loss of attachment score 0) [Table 1]. Among this study population, the total periodontal disease burden is 75% [Table 2] with 72% having gingivitis, 3% having periodontitis, and 25% being periodontally healthy.

Table 1.

Percentage of students by their highest community periodontal index score in the study participants

Table 2.

Distribution of periodontal health status among school children aged 15-17 years in Kozhikode district

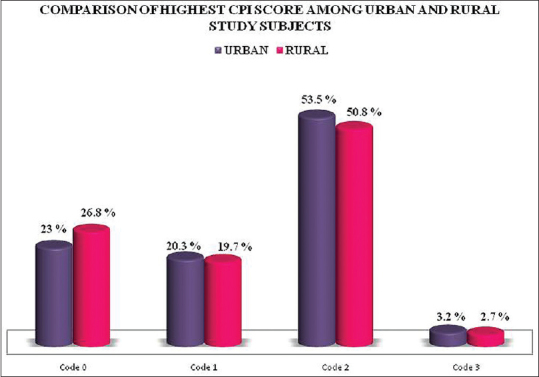

The prevalence of periodontal disease was more in the urban population. Bleeding on probing was detected in 20.3% of the urban population as compared to 19.7% of rural population. About 53.5% of the urban population had calculus deposits, whereas the rural population comprises of 50.8%. In urban population, 3.2% had periodontal destruction, and in rural population, it was 2.7% [Figure 3]. About 77% of the urban population experienced periodontal disease either gingivitis or periodontitis, whereas in the rural population, it was 73.2% and this difference was statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Comparison of distribution of students by the highest community periodontal index score in rural and urban areas. CPI: Community periodontal index

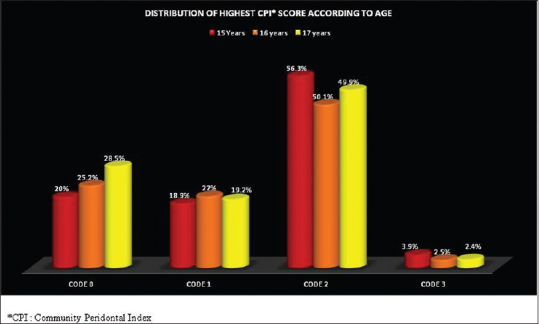

The periodontal disease burden in 15 years, 16 years, and 17 years old students was found to be 79.1%, 74.8%, and 71.5%, respectively, and the difference between the age groups was found to be statistically significant [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Distribution of highest community periodontal index score according to age

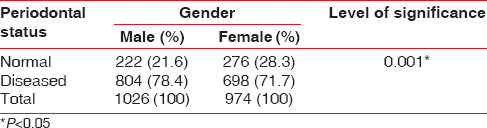

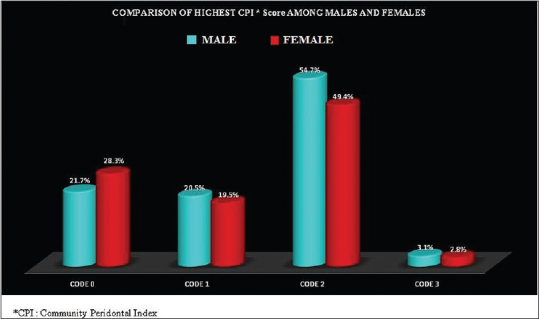

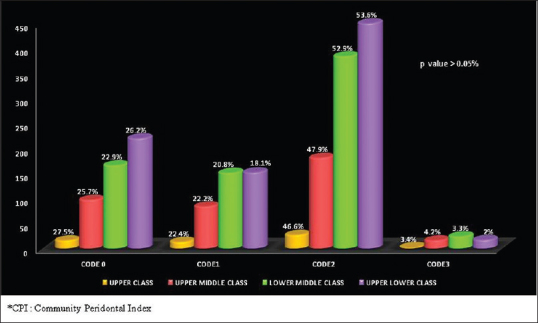

Periodontal disease was present among 78.4% of the males as compared to 71.7% in the females and the difference was statistically significant [Table 3]. Distribution of highest CPI Score according to gender is depicted in Figure 5. The prevalence of periodontal disease was more in the lower socioeconomic strata [Figure 6].

Table 3.

Distribution of periodontal health status according to gender

Figure 5.

Distribution of highest community periodontal index score among males and females

Figure 6.

Distribution of highest community periodontal index score according to socioeconomic status

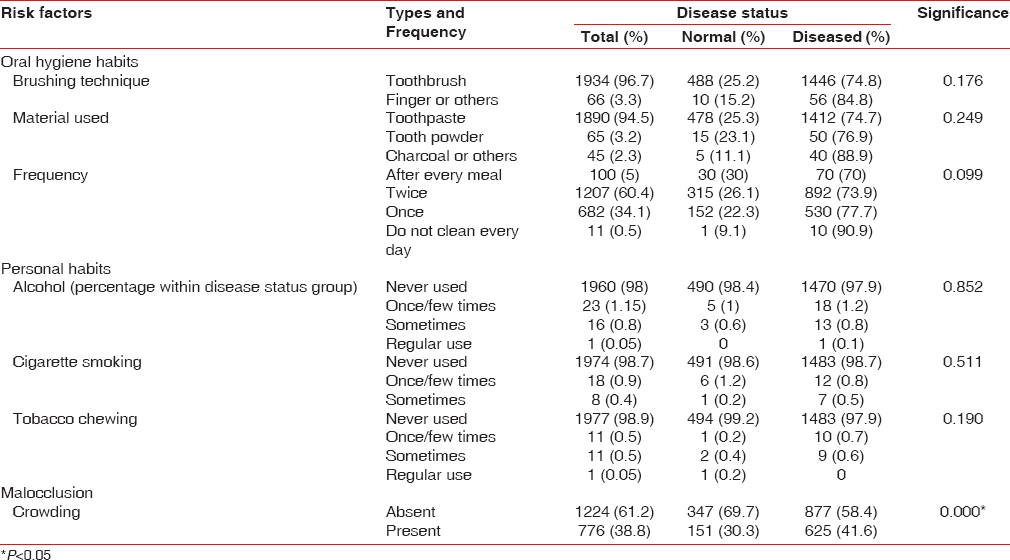

An assessment of the impact of modifiable risk factors such as oral hygiene practices, personal habits and anatomic factors such as crowding on the periodontal health status of the study participants was done. Among the study population, 96.7% of the students were using toothbrush, and among these, 74.8% had periodontal disease. Although 94.5% of the study population used toothpaste, 74.7% of them had periodontal disease. Out of the 60.4% of the study population who brushed twice daily, 73.9% had periodontal disease [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of modifiable risk factors among periodontally diseased and normal study participants

About 4% of the study population had personal deleterious habits such as smoking, alcohol usage, and tobacco chewing. Nearly 41.6% of periodontally diseased (gingivitis or periodontitis) participants had statistically significant crowding.

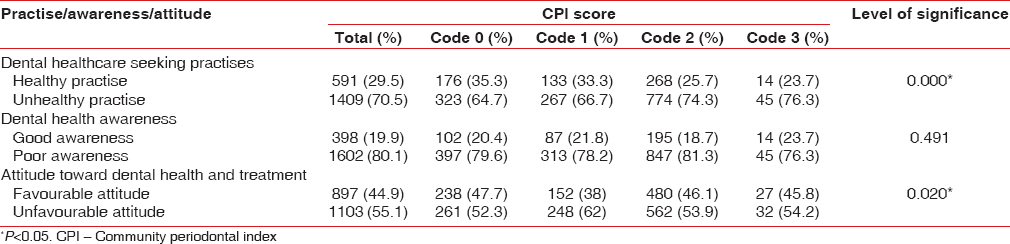

Table 5 shows the effect of DTSP, DA, and ATDT on the periodontal health status analysis. Out of the study population, 70.5% was found to have unhealthy DTSP. Out of these, 66.7% had bleeding on probing (Code 1) as compared to 33% with healthy practices [Table 5]. In code 2 (calculus deposits), 74.3% had unhealthy DTSP. Among those with periodontitis (4–5 mm pockets [Code 3]), 76.3% belonged to the group with unhealthy DTSP. These differences were statistically significant. This indicates that unhealthy DTSP act as a risk factor for the development of periodontal disease. Poor DA was seen among 80.1% of the respondents. Among Code 1, Code 2, and Code 3, 78.2%, 81.3%, and 76.3%, respectively, had poor awareness. Although the percentage of students with poor dental awareness was high, its effect on periodontal health status was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Practise, awareness and attitude among study participants

About 55.2% of the study participants showed an unfavorable attitude toward dental health and treatment. Assessment of the effect of ATDT on highest CPI score showed that 62% of participants with Code 1, 53.9% with Code 2, and 54.2% with Code 3 had an unfavorable attitude. The association of ATDT with periodontal disease was found to be statistically significant.

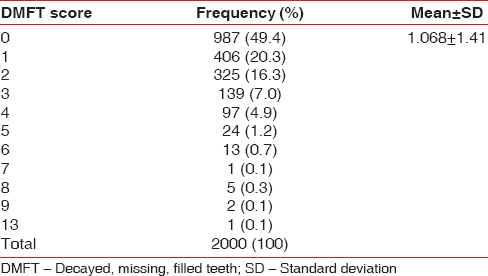

The mean DMFT was found to be 1.068 (±1.413). The prevalence of dental caries among the study participants was found to be 50.6% [Table 6].

Table 6.

Decayed missing filled teeth score for the study population

DISCUSSION

The overall oral health depends on the health of teeth and supporting structures which in turn is influenced by the attitude and awareness of the participant about oral health and dental treatment. Relative risks of various risk factors in periodontal disease, overtime, have been investigated by means of epidemiologic surveys and clinical studies.[11,12,13,14]

Periodontitis is always preceded by gingivitis,[15] and it is widely accepted that marginal gingivitis begins in early childhood, increases in prevalence and severity to the early teenage years. Thus, the periodontal disease prevalence in children is an indicator of future disease burden in the adult population. Although various epidemiological studies were conducted in Kerala, overtime, no data is available regarding the prevalence of periodontal disease among the school children in Kozhikode district.

The high prevalence of periodontal disease (75%) found in this study was in accordance with earlier studies.[9,16] We observed 72% gingivitis and 3% periodontitis which is in accordance with a study by Singh in 2014.[9] Identifying the possible risk factors that are contributing to such a high prevalence of periodontal disease is vital to ameliorate the oral health status in the study population. In this study, we found that the prevalence of periodontal disease is higher by 4% in the urban population. This was in corroboration with Singh and Soni in 2005,[17] and they reported that advanced stages of periodontal disease are significantly more prevalent in urban areas as compared to rural areas in Ludhiana, Punjab. However, these findings are contrary to the findings in studies spanning rest of the country where rural areas were consistently found to have a higher prevalence of periodontal disease.[18,19] It is difficult to draw sharp demarcation between urban and rural areas in a state like Kerala. The population density of Kerala is 859 persons/km2 which is three times more than the national average. This would imply that all areas of Kerala are almost equally developed.[20] The comparatively higher prevalence of periodontal disease in the urban population found in this study could possibly be attributed to the dietary habits of the urban children that have a major proportion of junk food, which is mainly refined carbohydrates and sweet sticky food substances. Holmes and Collier[21] reported that the consistency of the diet may be responsible for reducing the efficiency and effectiveness of tooth brushing. In 2007, an in vitro study on the effect of some dietary components on calculus showed that carbohydrate and oil enhance calculus formation while side dishes of protein food would decrease it.[22]

Distribution of periodontal health status was assessed with respect to age; it was found that 15 years old had a higher proportion (79.1%) of periodontal disease as compared to 16 years (74.8%) and 17 years (71.5%). A peak in the prevalence and severity of gingivitis around the age 9–14 years, which coincides with prepuberty and puberty, is well documented.[2,23] The increase in gingivitis from infancy to puberty may be attributed to the increase in number of sites at risk, to the plaque accumulation and inflammatory changes associated with tooth eruption and exfoliation and to the influence of hormonal factors in puberty. The decline in gingivitis that is common during adolescence may reflect an increased social awareness and better oral hygiene.

In this study, periodontal disease either in the form of gingivitis or periodontitis was significantly more in males. This finding was supported by Das et al. 2009[24] and Mahesh Kumar et al. 2005.[25] Contrasting results were reported by Dhar et al. 2007[16] who observed higher prevalence in girls. In our study, boys showed a greater prevalence than girls probably because oral hygiene habits have a gender relation. Personal hygiene is more of concern for girls than boys, and a health-directed behavior is also seen more among girls than boys.[26]

The periodontal disease was more prevalent in the students belonging to the lower socioeconomic strata (lower-middle class and upper lower class). This is consistent with the study by Mathur et al. in 2016[27] which reported that there was a socioeconomic gradient in poor oral hygiene, with higher prevalence observed at each level of deprivation. The difference in periodontal disease burden among the different socioeconomic strata was not statistically significant in the present study. This could be attributed to the fact that Kerala (2011 census of India) has a high literacy rate of 93.91%.[20] Greater literacy rates imply greater awareness about oral hygiene habits as supported by a study by Gundala and Chava in 2010.[28]

It was interesting to see, however that, only very few of the study participants used the traditional oral hygiene materials. About 96.7% of the study participants used toothbrush as the cleaning aid, and 94.5% used toothpaste as oral hygiene material. These findings together with a brushing frequency of two times a day (60.4%), for the majority of study participants, demonstrate an increased awareness toward oral hygiene in the study population. However, it remains disturbing that even with such amount of awareness about oral hygiene, the prevalence of periodontal disease still remains at a high level of 75%. Furthermore, a large number of participants with CPI code 2 (calculus) were observed. This could possibly be attributed to the fact that 71% of the respondents had never been professionally taught the correct brushing technique, which points to a lack of Dental Health Promotion Program. Faulty tooth brushing technique leads to improper removal of plaque, especially from the interdental region, which overtime gets converted into calculus that further acts as a nidus for plaque accumulation and this vicious cycle continues resulting in bleeding and pocketing. In this study, even though the effect of personal habits (cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, and use of smokeless tobacco) on periodontal health status was statistically insignificant, interventions aiming to create awareness about the deleterious effects of these habits need to be undertaken as an emergency measure, considering the young age of the respondents.

The impact of crowding on the periodontal health status was statistically significant. This is consistent with a study by Ainamo in 1972.[29] However, in contrast to our study, Abu Alhaija and Al-Wahadni[30] reported that there was no association between irregularity of teeth and periodontal diseases in the presence of good oral hygiene. Hence, it was inferred that the high occurrence of periodontal disease in our study participants with crowding may be due to ineffective oral hygiene measures. Apart from the periodontal health status, overall caries prevalence was also high (50.6%).

It is alarming that in spite of the good awareness about oral hygiene (use of toothbrush and paste and brushing twice daily), the periodontal disease burden is quite high in the study participants. In this study, we also made an attempt to explore the DTSP, DA, ATDT among these participants. It is interesting to notice that high proportion of study participants had unhealthy DTSP and poor awareness about dental treatment. Majority of the respondents showed an unfavorable ATDT. A number of studies reported similar findings.[31,32] D'Cruz and Aradhya in 2013[33] observed that active involvement of school children with reinforcement of oral hygiene education can improve oral hygiene knowledge, practices, and gingival health and decrease plaque levels among 13–15-year-old school children.

One of the limitations of the study was that only government schools were selected. The usage of self-administered questionnaires despite its numerous advantages, introduces elements of information bias, in forms of recall and social desirability biases.

Unhealthy DTSP, poor awareness about and unfavorable ATDT have contributed to the high prevalence of periodontal disease and dental caries. Professional intervention in patient education and guidance for good oral hygiene practices are thus mandatory and call for the implementation of Oral Health Education programs is the need of the hour.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to

Mrs. Jayashree, the District Education Officer of the Kozhikode educational district, Kozhikode

Mrs. Sreelatha, the District Education Officer of the Thamarassery educational district, Kozhikode

Mr. Surash Kumar, the District Education Officer of the Vadakara educational district Kozhikode for their support and encouragement, by permitting us to conduct this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamm JW. Epidemiology of gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:360–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bimstein E, Matsson L. Growth and development considerations in the diagnosis of gingivitis and periodontitis in children. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on caries and periodontal disease in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:133–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badersten A, Egelberg J, Koch G. Effect of monthly prophylaxis on caries and gingivitis in schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1975;3:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1975.tb00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamp SE, Lindhe J, Fornell J, Johansson LA, Karlsson R. Effect of a field program based on systematic plaque control on caries and gingivitis in schoolchildren after 3 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1978;6:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1978.tb01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman HL. The health of adolescents: Beliefs and behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:309–15. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bali R, Mathur V, Talwar P, Chanana H. National Oral Health Survey and Fluoride Mapping 2002-2003 India. Dental Council of India and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Government of India) 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh AK. Prevalence of gingivitis and periodontitis among schools children in Lucknow region of Uttar Pradesh, India. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gururaj M. Kuppuswamy's socio-economic status scale-a revision of income parameter for 2014. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2014;11:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden GJ, Mullally BH. Cigarette smoking and periodontal destruction in young adults. J Periodontol. 1994;65:718–23. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albandar JM. Periodontal diseases in North America. Periodontol 2000. 2002;29:31–69. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Axelsson PA. Commentary: Periodontitis is preventable. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1303–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhar V, Jain A, Van Dyke TE, Kohli A. Prevalence of gingival diseases, malocclusion and fluorosis in school-going children of rural areas in Udaipur district. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25:103–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.33458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh G, Soni B. Prevalence of periodontal diseases in urban and rural areas of Ludhiana, Punjab. Indian J Commu Med. 2005;30:128–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene JC. Periodontal disease in India: Report of an epidemiological study. J Dent Res. 1960;39:302. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramfjord SP, Emslie RD, Greene JC, Held AJ, Waerhaug J. Epidemiological studies of periodontal diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1968;58:1713–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.58.9.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Registrar General I. Census of India 2011: Provisional Population Totals-India Data Sheet. Office of the Registrar General Census Commissioner, India. Indian Census Bureau. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes CB, Collier D. Periodontal disease, dental caries, oral hygiene and diet in adventist and other teenagers. J Periodontol. 1966;37:100–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1966.37.2.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hidaka S, Oishi A. An in vitro study of the effect of some dietary components on calculus formation: Regulation of calcium phosphate precipitation. Oral Dis. 2007;13:296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutcliffe P. A longitudinal study of gingivitis and puberty. J Periodontal Res. 1972;7:52–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1972.tb00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das UM, Beena JP, Azher U. Oral health status of 6 - And 12-year-old school going children in Bangalore city: An epidemiological study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2009;27:6–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.50809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahesh Kumar P, Joseph T, Varma RB, Jayanthi M. Oral health status of 5 years and 12 years school going children in Chennai city – An epidemiological study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2005;23:17–22. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.16021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaborskyte A, Bendoraitiene E. Oral hygiene habits and complaints of gum bleeding among schoolchildren in Lithuania. Stomatologija. 2003;5:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathur MR, Tsakos G, Parmar P, Millett CJ, Watt RG. Socioeconomic inequalities and determinants of oral hygiene status among Urban Indian adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:248–54. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gundala R, Chava VK. Effect of lifestyle, education and socioeconomic status on periodontal health. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.62516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ainamo J. Relationship between malalignment of the teeth and periodontal disease. Scand J Dent Res. 1972;80:104–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1972.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abu Alhaija ES, Al-Wahadni AM. Relationship between tooth irregularity and periodontal disease in children with regular dental visits. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;30:296–8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.30.4.gu76270w876250p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen LB, Petersen PE, Bhambal A. Oral health and oral health behaviour among 11-13-year-olds in Bhopal, India. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Omiri MK, Al-Wahadni AM, Saeed KN. Oral health attitudes, knowledge, and behavior among school children in North Jordan. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Cruz AM, Aradhya S. Impact of oral health education on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, plaque control and gingival health of 13 to 15-year-old school children in Bangalore city. Int J Dent Hyg. 2013;11:126–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2012.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]