Abstract

Purpose: To determine the clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) according to different histological subtypes.

Methods: Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, we included TNBC cases in 2010-2013. The effect of histological subtype on breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed using univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results: A total of 19,900 patients were identified. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified accounted for 91.6% of patients, followed by metaplastic carcinoma (2.7%), medullary carcinoma (1.4%), mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (1.4%), lobular carcinoma (1.3%), apocrine carcinoma (1.0%), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (0.6%). Medullary carcinoma was more frequently poorly/undifferentiated. Significantly more lobular carcinoma, mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma, and metaplastic carcinoma patients had larger tumors. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, and apocrine carcinoma were more frequently node-negative. Lobular carcinoma (16.0%) and mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (10.4%) more frequently had distant stage at initial diagnosis. Histologic subtype was an independent prognostic factor of BCSS and OS. Compared with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, medullary carcinoma and apocrine carcinoma had better BCSS and OS, while mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma and metaplastic carcinoma had worse survival. Adenoid cystic carcinoma survival was not significantly different from that of infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

Conclusions: TNBC histological subtypes have different clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes. Medullary carcinoma and apocrine adenocarcinoma have excellent prognosis; mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma and metaplastic carcinoma are the most aggressive subtypes.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Triple-negative, histological subtype, Survival outcomes.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Prognoses and responses to treatment of its subtypes differ based on estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status 1-3. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined as the negativity for hormone receptors (estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor) and HER2 status, accounts for about 15-20% of breast cancer patients. Recurrence rates are particularly high within the first years; relapse risk is highest 3 years after surgery, and the risk of recurrence decreases rapidly 4. TNBC is also considered a heterogeneous subtype; the prognostic role of classic pathological characteristics such as tumor size, nodal status, and tumor grade could be impaired in patients with TNBC 5.

Histologically, TNBC is a highly heterogeneous disease. Most patients with TNBC have invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS). The remaining 10-25% of patients comprise medullary carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, apocrine carcinoma, and mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma 5-9. Morphological classification of these specific histological subtypes is very important, as tumor behavior and prognosis differ between subtypes. Studies on the clinicopathological characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of the different TNBC histological subtypes are limited 7, 8. In the present study, we used a population-based national registry (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results, SEER) to investigate the clinicopathological features, treatment, and survival outcomes of TNBC patients based on their histological subtypes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Data were obtained from the current SEER dataset, which is maintained by the National Cancer Institute and consists of 18 population-based cancer registries 10. Patients with female TNBC as the primary cancer were diagnosed with positive histology, and the diagnosis of specific histological subtypes required more than 100 cases. Tumors were classified based on their primary site of presentation using the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3). Access to SEER database data did not require informed patient consent, and the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Cancer Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, approved this study.

Demographic and clinical variables

The relationship between histological subtypes and clinical characteristics, including year of diagnosis, age, race/ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor size, nodal status, distant metastatic status, and treatment was analyzed. The primary endpoints were breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc.). Differences between qualitative data were analyzed using the χ2 and Fisher exact probability tests. Continuous variables in patients were compared using analysis of variance. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. Significant and independent risk factors of BCSS and OS were identified by Cox proportional hazard models. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

We included 19,900 patients in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of the TNBC patients according to histological subtypes. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS accounted for about 91.6% of patients (18,233), followed by metaplastic carcinoma (2.7%, 538), medullary carcinoma (1.4%, 278), mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (1.4%, 269), lobular carcinoma NOS (1.3%, 268), apocrine adenocarcinoma (1.0%, 199), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (0.6%, 115). The median follow-up was 20 months.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | n | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS (%) | Lobular carcinoma NOS (%) | Mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (%) | Medullary carcinoma (%) | Metaplastic carcinoma (%) | Apocrine adenocarcinoma (%) | Adenoid cystic carcinoma (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 18233 | 268 | 269 | 278 | 538 | 199 | 115 | ||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 57.8±13.9 | 57.5±13.8 | 65.9±13.5 | 60.4±15.1 | 53.5±13.2 | 62.5±14.1 | 66.0±12.6 | 59.3±12.9 | < 0.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| 2010 | 4954 | 4511 (24.7) | 71 (26.5) | 70 (26.0) | 88 (31.7) | 124 (23.0) | 58 (29.1) | 32 (27.8) | 0.097 |

| 2011 | 5104 | 4652 (25.5) | 70 (26.1) | 80 (29.7) | 67 (24.1) | 153 (28.4) | 55 (27.6) | 27 (23.5) | |

| 2012 | 4964 | 4570 (25.1) | 77 (28.7) | 51 (19.0) | 66 (23.7) | 132 (24.5) | 41 (20.6) | 27 (23.5) | |

| 2013 | 4878 | 4500 (24.7) | 50 (18.7) | 68 (25.3) | 57 (20.5) | 129 (24.0) | 45 (22.6) | 29 (25.2) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-hispanic white | 12001 | 10929 (59.9) | 183 (68.3) | 179 (66.5) | 120 (43.2) | 368 (68.4) | 133 (66.8) | 89 (77.4) | < 0.001 |

| Non-hispanic black | 3962 | 3688 (20.2) | 34 (12.7) | 38 (14.1) | 78 (28.1) | 79 (14.7) | 30 (15.1) | 15 (13.0) | |

| Hispanic | 2404 | 2197 (12.0) | 29 (10.8) | 37 (13.8) | 64 (23.0) | 57 (10.6) | 15 (7.5) | 5 (4.3) | |

| Other and unknown | 1533 | 1419 (7.8) | 22 (8.2) | 15 (5.6) | 16 (5.8) | 34 (6.3) | 21 (10.6) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Tumor grade | |||||||||

| Well differentiated | 375 | 268 (1.5) | 19 (7.1) | 9 (3.3) | 3 (1.1) | 17 (3.2) | 11 (5.5) | 48 (41.7) | < 0.001 |

| Moderately differentiated | 3307 | 2845 (15.6) | 144 (53.7) | 98 (36.4) | 7 (2.5) | 60 (11.2) | 119 (59.8) | 34 (29.6) | |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 15442 | 14505 (79.5) | 70 (26.1) | 157 (58.4) | 251 (90.3) | 389 (72.3) | 61 (30.7) | 9 (7.8) | |

| Unknown | 776 | 615 (3.4) | 35 (13.1) | 5 (1.9) | 17 (6.1) | 72 (13.4) | 8 (4.0) | 24 (20.9) | |

| Tumor size | |||||||||

| T0 | 22 | 19 (0.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| T1 | 8316 | 7699 (42.2) | 91 (34.0) | 99 (36.8) | 119 (42.8) | 124 (23.0) | 123 (61.8) | 61 (53.0) | |

| T2 | 8215 | 7509 (41.2) | 92 (34.3) | 104 (38.7) | 142 (51.1) | 264 (49.1) | 54 (27.1) | 50 (43.5) | |

| T3 | 1695 | 1494 (8.2) | 45 (16.8) | 36 (13.4) | 10 (3.6) | 95 (17.7) | 13 (6.5) | 2 (1.7) | |

| T4 | 1231 | 1118 (6.1) | 30 (11.2) | 20 (7.4) | 5 (1.8) | 50 (9.3) | 8 (4.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 421 | 394 (2.2) | 8 (3.0) | 10 (3.7) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Nodal stage | |||||||||

| N0 | 12546 | 11401 (62.5) | 140 (52.2) | 124 (46.1) | 212 (76.3) | 420 (78.1) | 138 (69.3) | 111 (96.5) | < 0.001 |

| N1 | 4879 | 4574 (25.1) | 59 (22.0) | 78 (29.0) | 46 (16.5) | 80 (14.9) | 40 (20.1) | 2 (1.7) | |

| N2 | 1240 | 1142 (6.3) | 21 (7.8) | 29 (10.8) | 13 (4.7) | 23 (4.3) | 12 (6.0) | 0 (0) | |

| N3 | 992 | 897 (4.9) | 40 (14.9) | 31 (11.5) | 4 (1.4) | 11 (2.0) | 9 (4.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 243 | 219 (1.2) | 8 (3.0) | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Metastases status | |||||||||

| M0 | 18811 | 17251 (94.6) | 225 (84.0) | 241 (89.6) | 276 (99.3) | 509 (94.6) | 194 (97.5) | 115 (100) | < 0.001 |

| M1 | 1089 | 982 (5.4) | 43 (16.0) | 28 (10.4) | 2 (0.7) | 29 (5.4) | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | 8159 | 7442 (40.8) | 126 (47.0) | 107 (39.8) | 119 (42.8) | 231 (42.9) | 91 (45.7) | 43 (37.4) | 0.456 |

| Married | 10625 | 9757 (53.5) | 135 (50.4) | 147 (54.6) | 142 (51.1) | 279 (51.9) | 99 (49.7) | 66 (57.4) | |

| Unknown | 1116 | 1034 (5.7) | 7 (2.6) | 15 (5.6) | 17 (6.1) | 28 (5.2) | 9 (4.5) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Surgery | |||||||||

| No | 1406 | 1296 (7.1) | 43 (16.0) | 28 (10.4) | 8 (2.9) | 25 (4.6) | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 18232 | 16686 (91.5) | 220 (82.1) | 237 (88.1) | 268 (96.4) | 513 (95.4) | 194 (97.5) | 114 (99.1) | |

| Unknown | 262 | 251 (1.4) | 5 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 9463 | 8636 (47.4) | 151 (56.3) | 132 (49.1) | 125 (45.0) | 278 (51.7) | 93 (46.7) | 48 (41.7) | 0.033 |

| Yes | 9368 | 8621 (47.3) | 103 (38.4) | 123 (45.7) | 130 (46.8) | 234 (43.5) | 93 (46.7) | 64 (55.7) | |

| Unknown | 1069 | 976 (5.4) | 14 (5.2) | 14 (5.2) | 23 (8.3) | 26 (4.8) | 13 (6.5) | 3 (2.6) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No/unknown | 5402 | 4757(26.1) | 117(43.7) | 87 (32.3) | 62 (22.3) | 188 (34.9) | 86 (43.2) | 105 (91.3) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 14498 | 13476 (73.9) | 151(56.3) | 182 (67.7) | 216 (77.7) | 350 (65.1) | 113 (56.8) | 10 (8.7) |

N, node; NOS, not otherwise specified; M, metastasis; SD, standard deviation; T, tumor.

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics according to histological subtypes. The mean age of lobular carcinoma NOS (65.9 years) and apocrine adenocarcinoma (66.0 years) was higher than the other subtypes (range, 53.5-62.5 years). Medullary carcinoma was more frequent in black patients (28.1%) than the other subtypes (range, 12.7-20.2%). Medullary carcinoma was also more frequently of poorly/undifferentiated (90.3%) than the other subtypes (infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS, 79.5%; metaplastic carcinoma, 72.3%; mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma, 58.4%; apocrine adenocarcinoma, 30.7%; lobular carcinoma NOS, 26.1%; adenoid cystic carcinoma, 7.8%).

Significantly more patients with lobular carcinoma NOS, mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma, and metaplastic carcinoma had larger tumor (T3-4). There was negative lymph node involvement in 96.5% of adenoid cystic carcinomas, 78.1% of metaplastic carcinomas, 76.3% of medullary carcinomas, and 69.3% of apocrine adenocarcinomas; 46.1-62.5% of infiltrating ductal and/or lobular carcinoma was node-negative. Patients with lobular carcinoma NOS (16.0%) and mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (10.4%) more frequently had distant stage at initial diagnosis and most did not undergo local surgery.

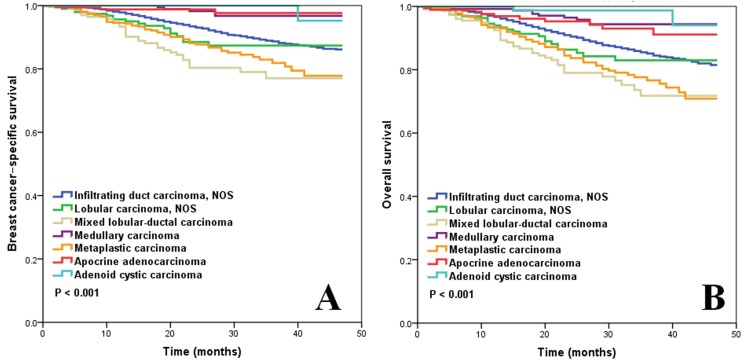

Figure 1A shows the BCSS according to histological subtypes of M0 patients who underwent local surgery (n=17,738). Mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma had the worst survival: the 3-year BCSS rate was 77.1%. The 3-year BCSS rate of infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS, lobular carcinoma NOS, and metaplastic carcinoma was, 88.9%, 87.4%, and 81.9%, respectively. Medullary carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma had better BCSS, where the 3-year BCSS rate was 96.6%, 97.7%, and 100%, respectively (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

BCSS (A) and OS (B) of TNBC for different histological subtypes.

Figure 1B shows the OS according to histological subtypes of M0 patients who underwent local surgery. The 3-year OS rate for patients with mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma, infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS, lobular carcinoma NOS, and metaplastic disease was 71.8%, 85.1%, 83.0%, and 76.8%, respectively. Medullary carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma had better OS than the other subtypes: the 3-year OS rate was 94.0%, 93.0%, and 98.7%, respectively (p < 0.001).

Univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 2 and 3, respectively) were performed on 17,738 M0 patients who underwent surgery. In univariate analysis, patients with medullary carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma had better BCSS and OS compared to patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Conversely, patients with mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma, and metaplastic carcinoma had worse BCSS and OS compared to patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors of BCSS and OS.

| Characteristic | BCSS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p | HR | 95%CI | p | |

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.010 | 1.006-1.014 | < 0.001 | 1.027 | 1.023-1.030 | < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-hispanic white | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Non-hispanic black | 1.287 | 1.120-1.478 | < 0.001 | 1.255 | 1.115-1.413 | < 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.960 | 0.796-1.159 | 0.673 | 0.855 | 0.724-1.010 | 0.065 |

| Other and unknown | 0.747 | 0.577-0.967 | 0.027 | 0.744 | 0.598-0.925 | 0.008 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.630 | 0.858-3.099 | 0.136 | 1.785 | 1.039-3.067 | 0.036 |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 2.551 | 1.368-4.757 | 0.003 | 2.47 | 1.459-4.182 | 0.001 |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| T0-T1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| T2 | 2.759 | 2.357-3.229 | < 0.001 | 2.342 | 2.064-2.658 | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 7.076 | 5.876-8.521 | < 0.001 | 5.229 | 4.468-6.120 | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 11.667 | 9.553-14.249 | < 0.001 | 8.885 | 7.502-10.522 | < 0.001 |

| Nodal status | ||||||

| N0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| N1 | 3.108 | 2.697-3.581 | < 0.001 | 2.229 | 1.979-2.510 | < 0.001 |

| N2 | 6.076 | 5.109-7.225 | < 0.001 | 4.307 | 3.709-5.002 | < 0.001 |

| N3 | 11.276 | 9.506-13.376 | < 0.001 | 7.862 | 6.784-9.113 | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.851 | 0.768-0.942 | 0.002 | 0.751 | 0.688-0.821 | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.000 | 0.878-1.139 | 0.998 | 0.656 | 0.592-0.726 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Married | 0.677 | 0.602-0.761 | < 0.001 | 0.583 | 0.527-0.645 | < 0.001 |

| Histological subtypes | ||||||

| Infiltrating duct carcinoma NOS | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Lobular carcinoma, NOS | 1.315 | 0.826-2.096 | 0.249 | 1.271 | 0.849-1.903 | 0.244 |

| Mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma | 2.380 | 1.674-3.383 | < 0.001 | 2.046 | 1.482-2.823 | < 0.001 |

| Medullary carcinoma | 0.252 | 0.105-0.607 | 0.002 | 0.368 | 0.198-0.686 | 0.002 |

| Metaplastic carcinoma | 1.798 | 1.371-2.358 | < 0.001 | 1.706 | 1.346-2.161 | < 0.001 |

| Apocrine adenocarcinoma | 0.219 | 0.071-0.680 | 0.009 | 0.532 | 0.286-0.990 | 0.047 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 0.125 | 0.018-0.891 | 0.038 | 0.183 | 0.046-0.730 | 0.016 |

BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; N, node; NOS, not otherwise specified; OS, overall survival; T, tumor.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors of BCSS and OS

| Characteristic |

BCSS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p | HR | 95%CI | p | |

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.014 | 1.010-1.019 | < 0.001 | 1.022 | 1.018-1.026 | < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-hispanic white | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Non-hispanic black | 1.159 | 1.004-1.338 | 0.044 | 1.196 | 1.058-1.351 | 0.004 |

| Hispanic | 0.876 | 0.724-1.061 | 0.177 | 0.876 | 0.740-1.038 | 0.128 |

| Other and unknown | 0.757 | 0.584-0.980 | 0.035 | 0.778 | 0.625-0.968 | 0.025 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.021 | 0.535-1.951 | 0.949 | 1.262 | 0.731-2.178 | 0.403 |

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 1.323 | 0.704-2.488 | 0.384 | 1.626 | 0.953-2.774 | 0.074 |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| T0-T1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| T2 | 2.043 | 1.737-2.403 | < 0.001 | 1.996 | 1.749-2.277 | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 3.999 | 3.279-4.877 | < 0.001 | 3.784 | 3.194-4.484 | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 4.745 | 3.819-5.896 | < 0.001 | 4.482 | 3.717-5.405 | < 0.001 |

| Nodal status | ||||||

| N0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| N1 | 2.514 | 2.168-2.915 | < 0.001 | 2.024 | 1.786-2.294 | < 0.001 |

| N2 | 4.296 | 3.574-5.163 | < 0.001 | 3.293 | 2.807-3.864 | < 0.001 |

| N3 | 6.891 | 5.722-8.299 | < 0.001 | 5.308 | 4.516-6.239 | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.675 | 0.599-0.761 | < 0.001 | 0.713 | 0.641-0.792 | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/unknown | — | 1 | ||||

| Yes | — | — | — | 0.617 | 0.545-0.700 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Married | 0.844 | 0.747-0.953 | < 0.001 | 0.787 | 0.708-0.876 | < 0.001 |

| Histological subtypes | ||||||

| Infiltrating duct carcinoma NOS | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Lobular carcinoma, NOS | 0.768 | 0.476-1.238 | 0.278 | 0.660 | 0.437-0.998 | 0.049 |

| Mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma | 1.682 | 1.178-2.402 | 0.004 | 1.447 | 1.045-2.004 | 0.026 |

| Medullary carcinoma | 0.327 | 0.136-0.788 | 0.013 | 0.479 | 0.257-0.893 | 0.021 |

| Metaplastic carcinoma | 1.634 | 1.235-2.163 | 0.001 | 1.334 | 1.043-1.706 | 0.022 |

| Apocrine adenocarcinoma | 0.219 | 0.070-0.683 | 0.009 | 0.486 | 0.260-0.907 | 0.023 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 0.300 | 0.042-2.162 | 0.232 | 0.299 | 0.074-1.213 | 0.091 |

BCSS, breast cancer-specific survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; N, node; NOS, not otherwise specified; OS, overall survival; T, tumor.

After adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor size, nodal status, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and marital status in Cox regression multivariate analysis, histological subtype remained an independent prognostic factor of BCSS and OS. Compared to patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, patients with medullary carcinoma (BCSS, hazard ratio [HR] 0.327, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.136-0.788, p = 0.013; OS, HR 0.479, 95% CI 0.257-0.893, p = 0.021) and apocrine adenocarcinoma (BCSS, HR 0.219, 95% CI 0.070-0.683, p = 0.009; OS, HR 0.486, 95% CI 0.260-0.907, p = 0.023) had better BCSS and OS. Conversely, patients with mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (BCSS, HR 1.682, 95% CI 1.178-2.402, p = 0.004; OS, HR 1.447, 95% CI 1.045-2.004, p = 0.026) and metaplastic carcinoma (BCSS, HR 1.634, 95% CI 1.235-2.163, p = 0.001; OS, HR 1.334, 95% CI 1.043-1.706, p = 0.022) had worse BCSS and OS. Lobular carcinoma NOS had better OS (HR 0.660, 95% CI 0.437-0.998, p = 0.049) bur not BCSS than infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS. The BCSS and OS of adenoid cystic carcinoma were not significantly different compared to survival in infiltrating ductal carcinoma (Table 3). Age, race/ethnicity, tumor size, nodal status, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, marital status were also the independent prognostic factors of survival outcomes.

Discussion

We assessed the clinicopathological characteristics and survival of TNBC according to histological subtypes using the SEER data. The histological subtypes had different clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes, demonstrating that TNBC can be divided into several distinct biological entities.

TNBC is a unique subtype of breast cancer with poor survival compared to other breast cancer subtypes. TNBC are histologically heterogeneous; apart from the predominant invasive ductal carcinoma, TNBC includes metaplastic, medullary, apocrine, adenoid cystic, and invasive lobular carcinomas 5-9. Due to the limited number of patients with the unique TNBC subtypes, previous studies did not find prognostic differences between the TNBC histological subtypes 7,8. In our study, the incidence of the specific histological subtypes was similar to that of previous studies 7,8. Taking infiltrating ductal carcinoma as the reference, multivariate analysis showed that patients with medullary carcinoma and apocrine carcinoma had excellent prognosis and that patients with metaplastic carcinoma and mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma had poor survival outcomes; adenoid cystic carcinoma had similar survival. The specific clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of each subtype could partly explain the differing reported outcomes.

Metaplastic carcinoma is a rare heterogeneous tumor of TNBC. About 50% of metaplastic carcinoma developed local or distant metastases within 5 years after surgery 11-13. Metaplastic carcinoma has larger tumors, less nodal positivity, and higher histologic grade. The survival outcomes are significantly worse than that of infiltrating ductal carcinoma 11,14,15. Dreyer et al. (n = 28) and Montagna et al. (n = 10), who had limited patients, did not report differences in metaplastic carcinoma survival as compared with invasive ductal carcinoma 7,8. In this study, the clinicopathological characteristics of metaplastic carcinoma were similar to that described above, and survival was significantly poorer than that of invasive ductal carcinoma. Metaplastic carcinoma has a higher histologic grade and high Ki-67 expression 8,11. Lien et al. found that epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related gene markers were differentially upregulated in metaplastic carcinoma compared to invasive ductal carcinoma 16. Hennessy et al. also found that the stem cell-like related markers were enriched in metaplastic carcinoma, rendering metaplastic carcinoma more likely to behave aggressively than infiltrating ductal carcinoma 17. These may account for the specific disease characteristics and poor prognosis of metaplastic carcinoma.

We found that mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma had significantly worse survival outcomes compared to invasive ductal carcinoma. Patients with lobular carcinoma NOS (16.0%) and mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma (10.4%) had more distant metastases at the initial diagnosis. Dreyer et al. also showed that, in newly diagnosed patients, invasive lobular carcinoma (20%) and mixed ductal-lobular carcinoma (100%) had a higher tendency to distant metastases compared to invasive ductal carcinoma (4.2%) 7, which could partly explain the worse prognosis of mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma in our study. In the multivariate analyses, the OS but not BCSS of lobular carcinoma NOS was better than infiltrating ductal carcinoma NOS. There are conflicting findings on the survival outcomes between lobular carcinoma and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in previous studies 18-20. The median follow-up of our study was only 20 months. Therefore, a longer follow-up time is need to confirm the survival difference between lobular carcinoma and infiltrating ductal carcinoma with TNBC.

Recurrence risk is higher in black patients and higher-grade TNBC 5, 21, 22. In our study, medullary carcinoma was more frequent in black patients and of higher histologic grade. However, we found excellent prognosis for medullary carcinoma. Our results are similar to that of previous studies 23,24. The excellent prognosis of medullary carcinoma could be explained through gene expression profiling. Vincent-Salomon et al. showed that cytokeratin 5/6 was expressed more frequently in medullary carcinoma 25, for which there is better patient survival 26. Moreover, Bertucci et al. reported a biological basis for the excellent prognosis of medullary carcinoma, which included effective host immune response, enhanced cancer cell apoptosis, upregulated expression of metastasis-inhibiting factors, and decreased expression of metastases-promoting factors 27. In addition, medullary-like TNBC has the characteristics of prominent inflammation and anastomosing sheets, and fewer tumors with fibrotic focus features, which are associated with better prognosis 28.

In our study, patients with apocrine adenocarcinoma subtype were more likely to be node-negative, well/moderately differentiated, and diagnosed at older age compared to the other subtypes, which is similar to that of previous studies 7, 29. These findings suggest that apocrine carcinoma may be less aggressive. In our study, apocrine adenocarcinoma was also a TNBC subtype with better survival. However, a previous study found that survival was similar in apocrine carcinoma and infiltrating ductal carcinoma 29. An immunohistochemical study found that apocrine-type TNBC more often had p53 overexpression, lower Ki-67 expression, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) overexpression compared to non-apocrine TNBC 30. However, p53 and EGFR overexpression in TNBC is associated with shorter survival 31-33, which does not shed light on the better survival of apocrine adenocarcinoma in our study. In our study, the better survival of apocrine adenocarcinoma as compared to infiltrating ductal carcinoma was mainly due to the presence of better clinical features, including node-negative status and well to moderate differentiation. Future studies should analyze the biological and survival differences between infiltrating ductal carcinoma and apocrine adenocarcinoma.

The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that adenoid cystic carcinoma had excellent prognosis, the 3-year BCSS and OS rates of adenoid cystic carcinoma were 100% and 98.7%, respectively. Multivariate analysis showed that survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma was not significantly different compared to that of infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The reason for these results is unclear. However, several studies have confirmed the excellent survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma 34, 35.

In this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. The first is the inherent biases in any retrospective study. However, the primary strength of the present study is that we were able to describe the epidemiology, prognostic factors, and treatment trends of these rare histological subtypes of TNBC using a SEER registry. Second, the SEER database does not include information on central pathology review, margin status, lymphovascular invasion, details of radiation therapy and chemotherapy, and local and distant recurrence data. Third, the data of radiotherapy and chemotherapy had a high specificity but the overall sensitivity was 80% and 68% in the current SEER program, respectively 36. In addition, the median follow-up time was only 20 months, as the SEER database only began recording HER2 statuses in 2010.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that the unique histological subtypes of TNBC is associated with different clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes. Medullary carcinoma and apocrine adenocarcinoma have excellent prognosis, while mixed lobular-ductal carcinoma and metaplastic carcinoma are the most aggressive subtypes and require adjuvant systemic treatment. The histological subtypes of TNBC should be taken into consideration for tailoring treatment. Further studies are needed to confirm our results.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2016J01635), the Science and Technology Planning Projects of Xiamen Science & Technology Bureau (No. 3502Z20174070), and the Guangdong Medical Research Foundation (No. A2017023).

Abbreviations

- BCSS

breast cancer-specific survival

- CI

confidence interval

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD-O-3

International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition

- NOS

not otherwise specified

- OS

overall survival

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer.

References

- 1.Arvold ND, Taghian AG, Niemierko A. et al. Age, breast cancer subtype approximation, and local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(29):3885–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunstein LZ, Niemierko A, Shenouda MN. et al. Outcome following local-regional recurrence in women with early-stage breast cancer: impact of biologic subtype. Breast J. 2015;21(2):161–7. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu SG, He ZY, Li Q. et al. Predictive value of breast cancer molecular subtypes in Chinese patients with four or more positive nodes after postmastectomy radiotherapy. Breast. 2012;21(5):657–61. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4429–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouckaert O, Wildiers H, Floris G. et al. Update on triple-negative breast cancer: prognosis and management strategies. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:511–20. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S18541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigelt B, Reis-Filho JS. Histological and molecular types of breast cancer: is there a unifying taxonomy? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(12):718–30. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreyer G, Vandorpe T, Smeets A. et al. Triple negative breast cancer: clinical characteristics in the different histological subtypes. Breast. 2013;22(5):761–6. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montagna E, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N. et al. Heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer: histologic subtyping to inform the outcome. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto Y, Iwase H. Clinicopathological features and treatment strategy for triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15(4):341–51. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Custom Data (with chemotherapy recode), Nov 2015 Sub (2000-2013) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S, 1969-2014 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released July 2016, based on the November 2015 submission. http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 11.Jung SY, Kim HY, Nam BH. et al. Worse prognosis of metaplastic breast cancer patients than other patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120(3):627–37. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayson D, Adjei AA, Suman VJ. et al. Metaplastic breast cancer: prognosis and response to systemic therapy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(4):413–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1008329910362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cimino-Mathews A, Verma S, Figueroa-Magalhaes MC. et al. A Clinicopathologic Analysis of 45 Patients With Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145(3):365–72. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqv097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luini A, Aguilar M, Gatti G. et al. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast, an unusual disease with worse prognosis: the experience of the European Institute of Oncology and review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101(3):349–53. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pezzi CM, Patel-Parekh L, Cole K. et al. Characteristics and treatment of metaplastic breast cancer: analysis of 892 cases from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(1):166–73. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lien HC, Hsiao YH, Lin YS. et al. Molecular signatures of metaplastic carcinoma of the breast by large-scale transcriptional profiling: identification of genes potentially related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2007;26(57):7859–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K. et al. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009;69(10):4116–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Yang J, Li S. et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: A special histological type compared with invasive ductal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0182397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim ST, Yu JH, Park HK. et al. A comparison of the clinical outcomes of patients with invasive lobular carcinoma and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast according to molecular subtype in a Korean population. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azim HA, Malek RA, Azim HA Jr. Pathological features and prognosis of lobular carcinoma in Egyptian breast cancer patients. Womens Health (Lond) 2014;10(5):511–8. doi: 10.2217/whe.14.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez CA, Zumsteg ZS, Gupta G. et al. Black race as a prognostic factor in triple-negative breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving therapy: a large, single-institution retrospective analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139(2):497–506. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao L, Gomez SL, Keegan TH. et al. Breast Cancer Mortality in African-American and Non-Hispanic White Women by Molecular Subtype and Stage at Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(7):1039–45. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu Z, Lin H, Liang X. et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of typical medullary breast carcinoma: a retrospective study of 117 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang XX, Jiang YZ, Liu XY. et al. Difference in characteristics and outcomes between medullary breast carcinoma and invasive ductal carcinoma: a population based study from SEER 18 database. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):22665–73. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent-Salomon A, Gruel N, Lucchesi C. et al. Identification of typical medullary breast carcinoma as a genomic sub-group of basal-like carcinomas, a heterogeneous new molecular entity. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(2):R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda T, Nakanishi Y, Hirotani Y. et al. Immunohistochemical co-expression status of cytokeratin 5/6, androgen receptor, and p53 as prognostic factors of adjuvant chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer. Med Mol Morphol. 2016;49(1):11–21. doi: 10.1007/s00795-015-0109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertucci F, Finetti P, Cervera N. et al. Gene expression profiling shows medullary breast cancer is a subgroup of basal breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2006;66(9):4636–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marginean F, Rakha EA, Ho BC. et al. Histological features of medullary carcinoma and prognosis in triple-negative basal-like carcinomas of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(10):1357–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeuchi H, Tsuji K, Ueo H. et al. Clinicopathological feature and long-term prognosis of apocrine carcinoma of the breast in Japanese women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88(1):49–54. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-9495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsutsumi Y. Apocrine carcinoma as triple-negative breast cancer: novel definition of apocrine-type carcinoma asestrogen/progesterone receptor-negative and androgen receptor-positive invasive ductal carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(5):375–86. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K. et al. Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(16):5367–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Y. Potential prognostic tumor biomarkers in triple-negative breast carcinoma. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2012;44(5):666–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C. et al. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1368–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun JY, Wu SG, Chen SY. et al. Adjuvant radiation therapy and survival for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Breast. 2017;31:214–18. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghabach B, Anderson WF, Curtis RE. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast in the United States (1977 to 2006): a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(4):R54. doi: 10.1186/bcr2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noone AM, Lund JL, Mariotto A. et al. Comparison of SEER Treatment Data With Medicare Claims. Med Care. 2016;54(9):e55–64. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]