Abstract

Modification of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins by the addition or removal of O-GlcNAc dynamically impacts multiple biological processes. Here, we present the development of a chemoenzymatic histology method for the detection of O-GlcNAc in tissue specimens. We applied this method to screen murine organs, uncovering specific O-GlcNAc distribution patterns in different tissue structures. We then utilized our histology method for O-GlcNAc detection in human brain specimens from healthy donors and donors with Alzheimer’s disease and found higher levels of O-GlcNAc in specimens from healthy donors. We also performed an analysis using a multiple cancer tissue array, uncovering different O-GlcNAc levels between healthy and cancerous tissues, as well as different O-GlcNAc cellular distributions within certain tissue specimens. This chemoenzymatic histology method therefore holds great potential for revealing the biology of O-GlcNAc in physiopathological processes.

Keywords: chemoenzymatic detection, GalT1, glycan labeling, histology, O-GlcNAc

Introduction

Modification of the amino acid residues serine and threonine by adding or removing O-GlcNAc has emerged as a critical post-translational modification that has a dynamic impact on multiple biological processes.[1] This form of glycosylation, which consists of a single N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) linked to serine or threonine residues, occurs primarily in nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins.[2] The addition and removal of O-GlcNAc from serine or threonine residues is a reversible process catalyzed by just two enzymes: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA).[3] OGT catalyzes the transfer of GlcNAc from a high-energy donor substrate (UDP-GlcNAc), which is an end product of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), providing a link to glucose metabolism, and serving as the basis for defining O-GlcNAc as a glucose sensor.[4] OGA in turn hydrolyzes O-GlcNAc from protein carriers and, together with OGT, dynamically regulates the cycling of O-GlcNAc.[3] Protein stabilization and transcriptional regulation are among other functional roles identified for the O-GlcNAc modification in addition to nutrient sensing.[5,6] It has been shown that O-GlcNAc can compete with and/or allosterically regulate phosphorylation in multiple proteins and that the crosstalk between O-GlcNAc and phosphorylation is a complex global system in which both post-translational modifications regulate each other and generate a vast array of chemical diversity amongst substrates.[7]

Aberrant O-GlcNAc modifications have been implicated in the pathology of metabolic[8,9] and neurodegenerative diseases,[10–12] as well as in cancers[13–15] and autoimmunity.[16] Therefore, reliable methods for O-GlcNAc monitoring and manipulation are in constant demand.[17] Although several anti-O-GlcNAc antibodies have proven useful in biological experiments, they are biased toward particular carrier proteins. Different anti-O-GlcNAc antibodies often show distinct detection profiles for the same specimens.[18,19]

A complementary method to antibody-based glycan detection is chemoenzymatic glycan labeling, which exploits unnatural nucleotide sugar donors equipped with a bioorthogonal chemical tag and glycosyltransferases to directly label specific glycan acceptor substrates.[20] This strategy has been used to detect Fucα (1–2)Gal,[21] N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc),[22] core 1 and 2 O-glycans,[23] and a few other higher order glycans.[20] Coincidentally, O-GlcNAcylation was originally discovered through a chemoenzymatic approach that exploited β1-4 galactosyltransferase (GalT1) to incorporate radiolabeled [3H]-Gal from UDP-[3H]-Gal to O-linked N-acetylglucosamine.[2] Subsequent refinement of this method and the development of a GalT1 mutant (Y289L) with donor promiscuity enabled the incorporation of a chemical tag to the donor substrate to replace the radioactive label.[24,25] This strategy has been extensively used to introduce various chemical tags to probe O-GlcNAc biology in cell lysates for downstream applications such as immunoblotting, proteomics,[26,27] as well as cellular imaging.[28] However, O-GlcNAc detection in histological specimens has barely been explored. Despite the discovery that aberrant O-GlcNAcylation is associated with multiple disease states, little is known about the distribution of O-GlcNAc across different organs and tissues. To date, no comprehensive histological study of O-GlcNAc has been reported.[29,30]

Previously, the Wu laboratory adapted chemoenzymatic LacNAc labeling to detect changes in LacNAc expression in tissue specimens, a method termed chemoenzymatic histology of membrane polysaccharides (CHoMP).[22,31] Here, we expanded the scope of CHoMP for the detection of O-GlcNAc in tissue samples by using GalT1 (Y289L) and highlight the power of this new method through the analysis of O-GlcNAc glycosylation patterns in murine tissues and human clinical specimens.

Results and Discussion

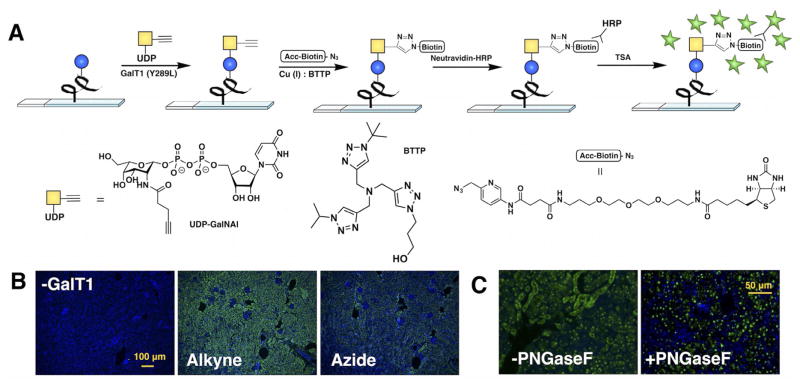

GalT1 (Y289L) is known to accept unnatural UDP-GalNAc analogues, including donors bearing ketone and azide groups. It has been shown that alkyne substrates coupled to a chelating azide probe through ligand-assisted copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) can increase the labeling efficiency up to 38-fold compared to the reaction with azide donors in flow cytometry experiments.[32] Therefore, we first assessed whether this enzyme could also accept an alkyne-bearing donor analogue. We chose BTTP, a ligand developed in our lab, for CuAAC because it has been shown to dramatically accelerate the rate of this reaction by coordination with the CuI generated in situ.[33,34] Using α-crystallin, an O-GlcNAc-bearing protein purified from bovine eye lens, we found that GalT1 (Y289L) could indeed accept the alkyne-tagged donor UDP-N-pentynylgalactosamine (UDP-GalNAl). However, when compared side-by-side with UDP-N-azidoacetylgalactosamine (UDP-GalNAz) in western blot analyses, GalT1 (Y289L) showed higher activity toward the azide donor (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Nevertheless, a combination of UDP-GalNAl and the accelerated biotin azide was found to afford a higher labeling signal in histological specimens (Figure 1B) in which neutravidin-HRP and tyramide signal amplification (TSA) were used for signal amplification.[31] The better labeling afforded by this protocol suggests that the high efficiency of the click reaction in the complex tissue environment might have compensated for the lower enzyme activity in the initial step.

Figure 1.

Development of a chemoenzymatic histology method for O-GlcNAc detection. A) General scheme for O-GlcNAc labeling on histological samples. B) Comparison between UDP-GalNAz and UDP-GalNAl donors, as well as a negative control lacking GalT1. C) Effect of pretreatment of tissue slides with PNG-aseF to remove nonspecific labeling. Histology images were acquired from 5 μm FFPE murine kidney tissue serial sections; Green = O-GlcNAc, blue = DAPI nuclear stain.

We further confirmed that GalT1 (Y289L) has unusual reaction conditions for tissue labeling compared with most glycosylation enzymes. Although most glycosyltransferases exhibited optimal activity at 37 °C, GalT1 (Y289L) preferred lower temperatures in histological specimens (e.g., 4°C; Figure S2). Furthermore, GalT1 (Y289L) on tissue sections required minimal concentrations (≈10–20 μg mL−1) for optimal activity, and the reaction efficiency surprisingly decreased with increasing concentrations (Figure S3), presumably due to self-inactivation. Donor concentration (Figure S4) and incubation time (Figure S5) behaved normally, with increased labeling correlating with longer reaction times or higher concentrations of donor until the signal reached a plateau. GalT1 (Y289L) was previously reported to possess nonspecific activity toward the acceptor substrate, accepting terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues in N-glycans.[35] Cell fractionation or pretreatment with PNGaseF to remove N-glycans is often employed to enhance specificity.[36] In histological specimens, pre-treatment with PNGaseF can also abolish N-glycan signals (Figure S6). In tissues pre-treated with PNGaseF, the highest signal intensity for O-GlcNAc labeling by GalT1 (Y289L) colocalized with DAPI nuclear stain (Figure 1C). The schematic representation of our optimized method for detection of O-GlcNAc in tissue sections is shown in Figure 1A.

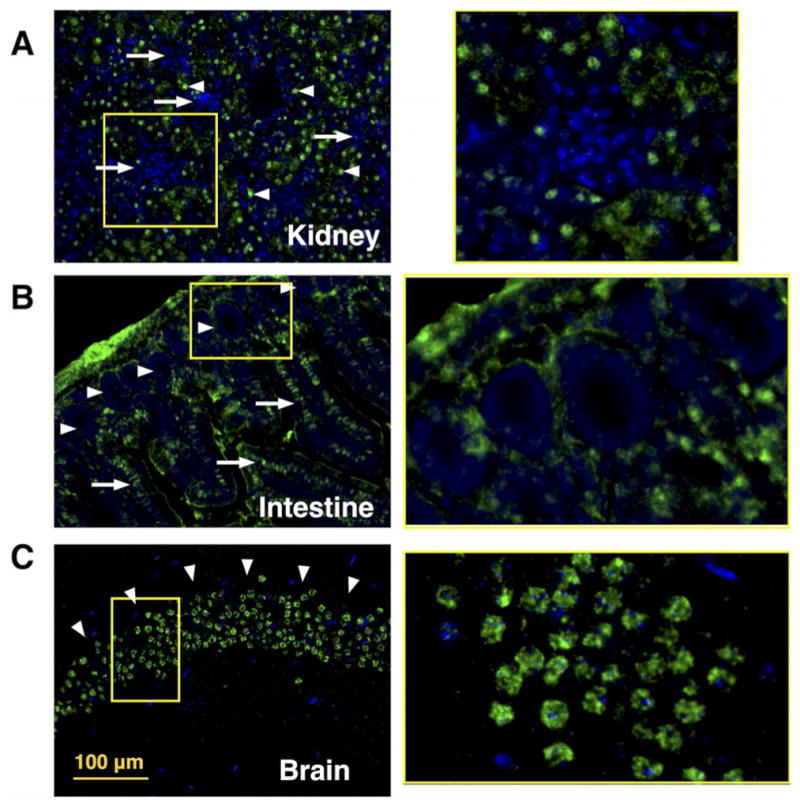

With an optimized protocol in hand, we proceeded to screen murine tissue specimens for O-GlcNAc distribution patterns. Although the cellular distribution of O-GlcNAc has been extensively studied in cell cultures and tissue homogenates, little is known about tissue distribution of O-GlcNAc, apart from the relative abundance of RNA transcripts encoding O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes (NCBI public database).[1] Using our O-GlcNAc chemoenzymatic histology analysis, we succeeded in determining the distribution of O-GlcNAc in mouse tissues including kidney, brain, and intestine (Figure 2), as well as in lung, stomach, testis, spleen, heart, skin, and pancreas (Figure S7). Most organs exhibited distinct patterns of O-GlcNAc expression in different tissue structures, and even within different cellular compartments. For example, duct cells in kidney showed the highest O-GlcNAc expression (Figure 2A), with the signal mostly localized to the nuclei. By contrast, very low levels of O-GlcNAc were observed in the glomeruli, the cluster of capillaries where waste products are filtered from the blood. In the intestine, most cells in the villi showed intense O-GlcNAc labeling, but the crypts located at the base of the villi, housing intestinal stem cells and niche cells, showed remarkably little staining (Figure 2B). In brain sections, we observed the highest O-GlcNAc expression localized to the hippocampus (Figure 2C), the elongated ridges on the floor of each lateral ventricle of the brain thought to be the center of emotion, memory, and the autonomic nervous system, which is consistent with a previous observation by antibody-based immunohistochemistry (IHC).[29] Notably, the resolution achieved by our chemoenzymatic histology method is significantly higher than that afforded by IHC. In lung sections, the cells in the alveoli showed significant O-GlcNAc staining, but little was observed in the bronchioles. In the testis, the seminiferous tubules stained strongly, whereas ducts in the epididymis showed a pattern of intercalating cells with high levels of O-GlcNAc. In the pancreas, most cells contained little O-GlcNAc; however, the Islets of Langerhans stained strongly. Hair follicles contained alternating cells with high levels of O-GlcNAc. A low O-GlcNAc signal was detected in murine spleen and stomach (Figure S7).

Figure 2.

O-GlcNAc distribution in murine organ samples as revealed by chemoenzymatic histology analysis. O-GlcNAc chemoenzymatic staining on 5 μm FFPE murine tissue sections; frames in right panels are amplifications of selected sections of left panels. Green = O-GlcNAc, blue = DAPI nuclear stain, Scale bar: 100 μm. A) Kidney: strong O-GlcNAc staining in ducts (arrowheads) and low O-GlcNAc signal in glomeruli (arrows); amplification shows a glomerulous. B) Intestine: O-GlcNAc labeling along the villi (arrows) and staining of the intestinal crypts (arrowheads); amplification shows a the crypt compartment. C) Brain: high O-GlcNAc signal localized in the brain hippocampus (arrowheards); amplification of a cross-section of hippocampus.

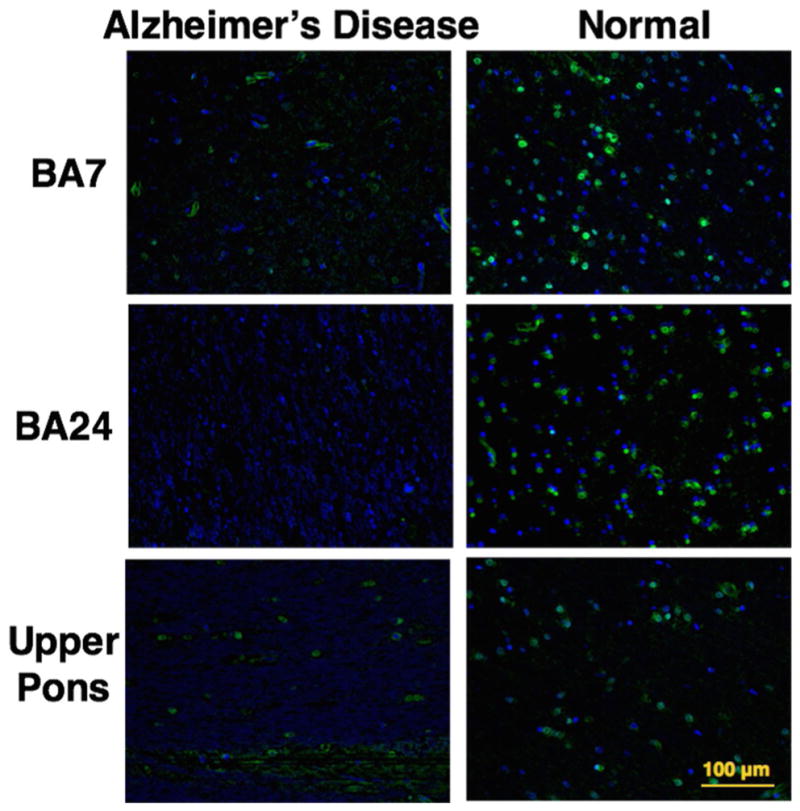

Having confirmed that distinct O-GlcNAc expression patterns could be characterized in murine tissue samples by using our chemoenzymatic histology method, we investigated whether this approach could be used to analyze human clinical samples. We chose brain samples as the first targets for our analysis. It has been observed that O-GlcNAc within the brain is present on hundreds of proteins, including tau and the amyloid precursor protein, which are involved in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease.[10] We obtained brain tissue sections from healthy donors and from donors with Alzheimer’s disease (Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center) and applied our chemoenzymatic histology method to examine O-GlcNAc expression. The difference in O-GlcNAc labeling was striking, clearly showing higher levels of O-GlcNAc labeling in healthy brain specimens versus brain specimens from patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Brodmann areas 7 and 24, as well as in the upper pons, but not on the cerebellum (Figures 3 and S8, n = 3). Our observation is consistent with previous studies that reported an overall decrease in O-GlcNAcylation in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by immunostaining of brain lysates, immunoprecipitation,[12] and IHC.[11] This experiment also nicely confirmed the utility of our chemoenzymatic histological method in clinical settings.

Figure 3.

Healthy brain tissues express higher levels of O-GlcNAc than brain tissues from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. O-GlcNAc chemoenzymatic staining of 5 μm FFPE human brain tissue sections, samples from Brodmann areas 7 and 24, and upper pons. Left: samples of brain tissue from Alzheimer’s disease patients; right: the same brain areas sampled from healthy donor brains. Green = O-GlcNAc, blue = DAPI nuclear stain, Scale bar: 100 μm.

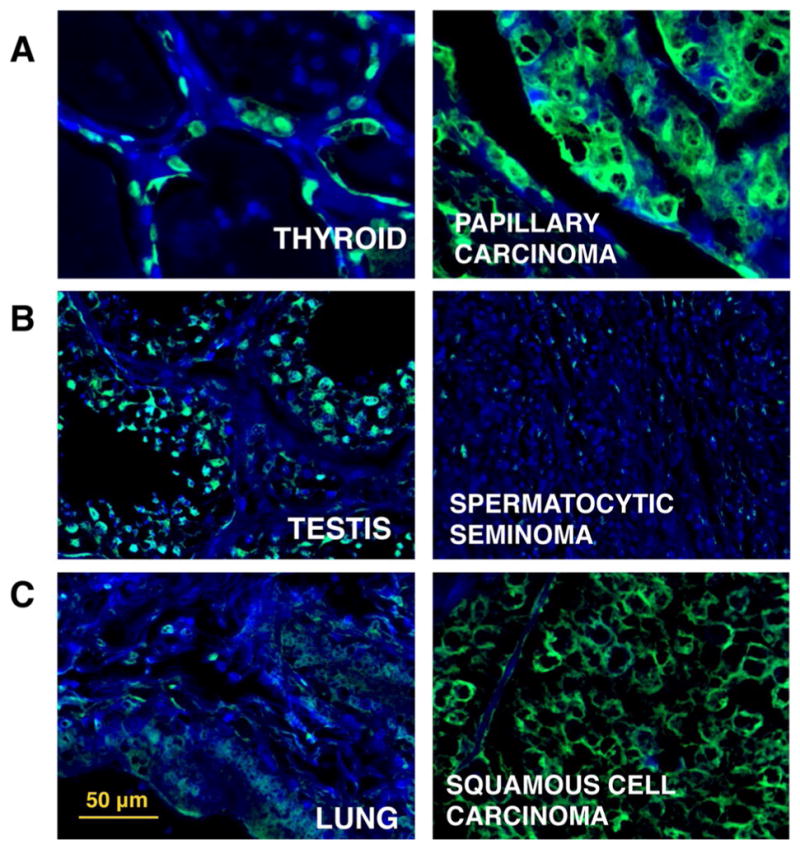

Multiple studies have provided evidence that aberrant levels of O-GlcNAc exist in breast,[37,38] colon,[39] and prostate cancer.[40] As a second application, we applied chemoenzymatic histology analysis of O-GlcNAc to a commercial tissue array containing normal and cancerous specimens from 12 different organs to examine the differences in O-GlcNAc expression. We observed pronounced differences between healthy and tumor specimens in most organs, particularly in thyroid, testis, and lung tissues. The key findings from our tumor array screening are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of O-GlcNAc levels and distribution between normal and cancerous tissues. O-GlcNAc chemoenzymatic staining by using multiple organ array MC245a (US Biomax) of FFPE human normal (left) and cancerous tissue (right). Green = O-GlcNAc, blue = DAPI nuclear stain, scale bar: 50 μm. a) Thyroid tissue versus papillary carcinoma: mainly nuclear staining in healthy tissue. Cancerous sample shows higher, mostly cytoplasmic O-GlcNAc signal. B) Testis tissue versus spermatocytic seminoma: high O-GlcNAc signal in healthy spermatocytes, but very low levels of labeling in cancerous sample. C) Lung tissue versus squamous cell carcinoma: low levels of staining in healthy lung, but high cytoplasmic O-GlcNAc labeling in cancerous sample.

It has been suggested that hyperproliferation of thyroid cancer cells might be related to an overall increase in O-GlcNAc levels.[41] Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed qualitatively higher staining in the cancerous tissue (papillary carcinoma) compared to the normal thyroid tissue (Figure 4A), which was confirmed by the quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the full tissue specimens and coverage area percentage of O-GlcNAc signal (Figure S9). Interestingly, in the healthy tissue, O-GlcNAc staining was located primarily in the nucleus, whereas a diffuse cytoplasmic signal was observed for cancerous specimens.

In testis, we observed that spermatocytes in the healthy tissue showed significant O-GlcNAc staining. By contrast, very little signal limited to a few scattered cells was detected in the spermatocytic seminoma specimen (Figures 4B and S8). We refrained from drawing population-wide conclusions from a single tissue specimen observation; however, most reports of aberrant O-GlcNAcylation in cancer have described increased levels of this post-translational modification linked to tumor hyperproliferation, the decrease in O-GlcNAc signal in seminoma might suggest a different proliferation mechanism.[42,43]

Although healthy lung tissue showed little O-GlcNAc staining, the lung squamous cell carcinoma sample showed a significant signal increase. Similar to what was observed for the thyroid cancer specimen, we detected a cytoplasmic staining pattern in the cancerous tissue (Figures 4C and S9). The observed higher O-GlcNAc staining levels with chemoenzymatic histology analysis were in agreement with a report observing an overall increase in O-GlcNAc expression in lung cancer.[39] Among other organs included in the array, prostate, colon, bladder, and larynx also showed increased O-GlcNAc staining in cancerous tissues compared to normal specimens. No significant differences were detected between tumor and normal tissues in tongue, lymph node, pancreas, and muscle specimens. The healthy breast core contained little ductal tissue to establish a relevant comparison (Figure S9).

Conclusions

In this work, we developed a method for the detection of O-GlcNAc in histological specimens based on chemoenzymatic glycan labeling. Valuable and integral information regarding the distribution of O-GlcNAc within organs and cell compartments can be obtained by using this strategy. By analyzing murine tissue sections, we uncovered patterns of differential O-GlcNAc distribution associated with tissue structures such as the hypothalamus in the brain, the glomeruli in the kidney, or the crypts in the intestine. We further applied this chemoenzymatic histology method to analyze human brain samples from healthy donors and donors with Alzheimer’s disease. Higher levels of O-GlcNAc were detected in specimens from healthy donor brains in agreement with published observations.[10] We then analyzed a multiple cancer tissue array discovering different O-GlcNAc levels between healthy and cancerous tissues, in addition to different O-GlcNAc cellular distribution for some specimen pairs. Our results suggest possible aberrant O-GlcNAc in spermatocytic seminoma, a form of cancer that has not yet been studied in the context of O-GlcNAcylation.

We are aware that no population-wide conclusions can be drawn from observations made from such a limited sample size. However, our results clearly demonstrated that chemoenzymatic glycan labeling can be applied to tumor biopsies to provide valuable information regarding distribution patterns of O-GlcNAc within tissue structures and cell compartments, as well as changes in O-GlcNAc levels during tumor development. As we previously reported for LacNAc-bearing glycans, chemoenzymatic histology analysis can generate quantitative information of glycan expression for tissue arrays with large sample sizes. Population-wide changes or possible trends related to tumor grade or stage can be discovered from such analysis.[31] Significantly, the efficacy and utility of chemoenzymatic histology for such applications has been validated by mass-spectrometry-based glycomics analysis.38

Experimental Section

General methods and materials

All reagents and solvents were acquired from Fisher Scientific and were used as received unless otherwise stated. Electrophoresis and western blotting were performed by using Bio-Rad equipment. Primary antibodies were obtained from various sources: O-GlcNAc antibody from Biolegend, GAPDH antibody from R&D Systems, and PARP antibody from TACS. α-Crystallin was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Photomicrographs were acquired on a BZ-X700 Keyence Microscope, and all images were processed by using ImageJ software. Statistical analysis and graph generation was completed by using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Human brain tissue specimens were obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. The human tissue array MC245a was purchased from US Biomax.

Mice

All animal studies were carried out under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Scripps Research Institute. C57BL/6 mice were bred and housed in the vivarium of The Scripps Research Institute, and were euthanized at 6–8 weeks and immediately perfused with 4 % formalin. Organs were harvested and immediately immersed in zinc formalin fixative for 24 h. Tissues were paraffin embedded by the TSRI Histology Core Facility and sectioned on a microtome at 5 μm.

Chemoenzymatic histology

Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated according to standard protocols. Specifically, the slides were sequentially immersed in coplin jars for 5 min in 40 mL of: Histo-Clear II (National Diagnostics) twice, ethanol twice, 70 % aqueous ethanol twice, 50 % aqueous ethanol twice and dH2O once. A hydrophobic barrier was drawn around the tissue samples on the slides with a PAP pen. Tissues were immersed in TBS +0.1 % Tween-20 (TBST, 50 mL) for 10 min. Slides were then placed in a humidified chamber, and PNGaseF NEB standard reaction solution (100 μL) was added (1× G1 buffer, 1 % NP-40, and 2 μL PNGaseF). Slides were incubated overnight at 37 °C, followed by TBST wash (3×5 min). Slides were placed again in a humidified chamber, and the enzyme solution was added. The enzyme solution contained GalT1 (25 μg mL−1), UDP-GalNAl (500 μM), MnCl2 (1 mμ), NaCl (50 mμ), HEPES (20 mμ), NP-40 (2 %), pH 7.9. The slides were incubated for 3 h at 4 °C. The slides were then washed with TBST (3×5 min). The slides were returned to a humidified chamber and blocked with avidin/biotin. Avidin solution (1 drop; Biolegend kit) was added to the tissue, and the slides were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed by TBST wash (3×3 min each). Biotin solution (1 drop) was then added to the tissue, and the slides were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed by TBST wash (3×3 min each). The slides were placed again in a humidified chamber and “clicked” to a biotin probe with a solution containing accelerated azide-biotin probe (50 μM),[32] CuSO4 (75 μM), BTTP ligand (150 μM), sodium ascorbate (2.5 mμ) in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Following three washes in TBST (5 min each), the tissues were blocked for 10 min in 0.3 % hydrogen peroxide diluted in TBS at room temperature and then washed with TBST (3×5 min) to remove the H2O2. The slides were placed in a humidified chamber and incubated with neutravidin-HRP (1:100 in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature, then subsequently washed with TBST (3×5 min). The slides were placed in a humidified chamber and incubated with TSA-Plus FITC reagent, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (1:50 dilution for 5 min at room temperature, protected from light), then washed with TBST (3×5 min) and mounted with Prolong anti-fade gold with Dapi (Invitrogen).

Image processing

All tissues were prepared with a negative control (same treatment without GalT1) in serial sections. Images were acquired at the maximum microscope gain to achieve 80 % signal saturation with a monochrome camera, and negative controls were acquired with the same acquisition parameters. By using Image J, minimum intensity was increased until signal was undetectable in negative controls, and this value was established as background and subtracted from each positive image. Pseudo RGB color was assigned to each channel, usually Green for O-GlcNAc and blue for nuclear DAPI stain. Each specimen pair in the tumor array (healthy and cancerous specimens from the same organ) were processed with the same parameters. MFI quantification was performed for the full tissue selection, and the percentage coverage area was determined by automatic particle selection after threshold setting (80/255) and comparison to the total tissue area.

Immunoblotting

In vitro test reactions were performed as described in the ThermoFisher O-GlcNAc Click-It kit with α-crystallin (50 μL). In short, α-crystallin (20 μg) was labeled overnight at 4 °C in a reaction solution (20 μL) containing MnCl2 (7.5 μM), UDP-GalNAz (25 μM), GalT1 (1 μg), NaCl (50 mμ), HEPES (20 mμ, pH 7.9), and NP-40 (2 %). The crude mixture was further diluted to 50 μL in a reaction solution containing accelerated azide-biotin probe (50 μM),[32] premixed CuSO4 (75 μM) and BTTP ligand (150 μM), and sodium ascorbate (2.5 mμ). The reaction mixture was shaken for 1 h at room temperature, and the crude mixture was directly loaded and run in 4–12 % Bis·Tris gels (Novex) with MES running buffer for 1.5 h at 100 V. Gels were then transferred by using Novex Blotting buffer onto nitrocellulose membranes at 300 mA for 2 h. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature by using 5 % powdered nonfat milk in TBST and subsequently incubated overnight with anti-biotin-HRP antibody (1:5000 in 5 % milk-TBST) at 4 °C with shaking. Membranes were then washed 3 × 5 min with TBST and SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoFisher) for 3 min and subjected to X-ray exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for samples provided by the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, which is supported in part by Public Health Service (PHS) contract HHS-NIH-NIDA (MH)-13-265. We thank the Histology Core Facility at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) for providing access to their equipment and support. This work was performed at TSRI with financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM113046 to P.W. and AI083754 and GM085267 to P.G.W.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information and the ORCID identification numbers for the authors of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201700515.

References

- 1.Bond MR, Hanover JA. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:869–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres CR, Hart GW. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:2208–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vocadlo DJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond MR, Hanover JA. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013;33:205–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaidyanathan K, Durning S, Wells L. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:140–163. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.884535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qina W, Lv P, Fan X, Quan B, Zhua Y, Qina K, Chen Y, Wang C, Chen X. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E6749–E6758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702688114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeidan Q, Hart GW. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:13–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springhorn C, Matsha TE, Erasmus RT, Essop MF. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4640–4649. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker G, Taylor R, Jones D, McClain D. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20636–20642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y, Shan X, Yuzwa SA, Vocadlo DJ. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:34472–34481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.601351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F, Shi J, Tanimukai H, Gu J, Gu J, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. Brain. 2009;132:1820–1832. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-iqbal I, Hart GW, Gong C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis RJ, Taylor EJ, Macauley MS, Stubbs KA, Turkenburg JP, Hart SJ, Black GN, Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fardini Y, Dehennaut V, Lefebvre T, Issad T. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Queiroz RM, Carvalho É, Dias WB. Front Oncol. 2014;4:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y, Tomic J, Wen F, Shaha S, Bahlo A, Harrison R, Dennis JW, Williams R, Gross BJ, Walker S, Zuccolo J, Deans JP, Hart GW, Spaner DE. Leukemia. 2010;24:1588–1598. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cecioni S, Vocadlo DJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashima Y, Stanley P. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11132–11142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comer FI, Vosseller K, Wells L, Accavitti MA, Hart GW. Anal Biochem. 2001;293:169–177. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguilar AL, Briard JG, Yang L, Ovryn B, Macauley MS, Wu P. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:611–621. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaubard JL, Krishnamurthy C, Yi W, Smith DF, Hsieh-Wilson LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4489–4492. doi: 10.1021/ja211312u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng T, Jiang H, Gros M, Del Amo DS, Sundaram S, Lauvau G, Marlow F, Liu Y, Stanley P, Wu P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4113–4118. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2011;123:4199–4204. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mbua NE, Li X, Flanagan-Steet HR, Meng L, Aoki K, Moremen KW, Wolfert MA, Steet R, Boons GJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:13012–13015. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2013;125:13250–13253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13132– 13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403471101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khidekel N, Arndt S, Lamarre-Vincent N, Lippert A, Poulin-Kerstien KG, Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK, Hsieh-Wilson LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16162–16163. doi: 10.1021/ja038545r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Clark PM, Bryan MC, Swaney DL, Rexach JE, Sun YE, Coon JJ, Peters EC, Hsieh-wilson LC. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rexach JE, Rogers CJ, Yu SH, Tao J, Sun YE, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:645–651. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark PM, Dweck JF, Mason DE, Hart CR, Buck SB, Peters EC, Agnew BJ, Hsieh-Wilson LC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11576–11577. doi: 10.1021/ja8030467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Li X, Yu Y, Shi J, Liang Z, Run X, Li Y, Grundke-iqbal I, Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong C-X. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes JW, Tian L, Heresi GA, Farver CF, Asosingh K, Comhair SAA, Aulak KS, Dweik RA. Circulation. 2015;131:1260–1268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouhanifard SH, Lopez-Aguilar A, Wu P. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:2667–2673. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang H, Zheng T, Lopez-Aguilar A, Feng L, Kopp F, Marlow FL, Wu P. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:698–706. doi: 10.1021/bc400502d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang W, Hong S, Tran A, Jiang H, Triano R, Liu Y, Chen X, Wu P. Chem Asian J. 2011;6:2796–2802. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.del Amo DS, Wang W, Jiang H, Besanceney C, Yan AC, Levy M, Liu Y, Marlow FL, Wu P. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16893–16899. doi: 10.1021/ja106553e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boeggeman E, Ramakrishnan C, Kilgore B, Khidekel N, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Simpson JT, Qasba PK. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:806–814. doi: 10.1021/bc060341n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J, Hart GW. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu Y, Mi W, Ge Y, Liu H, Fan Q, Han C, Yang J, Han F, Lu X, Yu W. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6344–6351. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sodi VL, Khaku S, Krutilina R, Schwab LP, Vocadlo DJ, Seagroves TN, Reginato MJ. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:923–933. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mi W, Gu Y, Han C, Liu H, Fan Q, Zhang X, Cong Q, Yu W. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2011;1812:514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itkonen HM, Gorad SS, Duveau DY, Martin SES, Barkovskaya A, Bathen TF, Moestue SA, Mills IG. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7039. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Krześlak A, JóŸwiak P, Lipińska A. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:743–749. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.JóŸwiak P, Forma E, Bryś M, Krześlak A. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5:145. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrer CM, Lynch TP, Sodi VL, Falcone JN, Schwab LP, Peacock DL, Vocadlo DJ, Seagroves TN, Reginato MJ. Mol Cell. 2014;54:820–831. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.