Abstract

Objectives

Low socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood may be associated with sleep in adulthood. We evaluated the relationships between SES in childhood through adolescence and into adulthood and sleep in mid-life men.

Design

Prospective assessment of SES in childhood and adulthood.

Setting

Population-based study of 139 Black and 105 White men enrolled since age 7 and evaluated for sleep characteristics at age 32.

Measurements

Actigraphy and diary measures of sleep duration, continuity, and quality for one week. Their parents reported their SES (a combination of educational attainment and occupational status) annually when the boys were ages 7 to 16. We estimated SES intercept (age 7) and slope (age 7 to 16) using M-Plus and conducted linear regression analyses using those values to predict adult sleep measures, adjusting for covariates.

Results

Men who had lower SES families at age 7, smaller increases in SES from ages 7 to 16, and lower SES in adulthood had more minutes awake after sleep onset. White men with greater increases in SES from ages 7 to 16 had shorter sleep.

Conclusions

SES in childhood and improvement in SES through adolescence are related to sleep continuity in mid-life men. To our knowledge this is the first report using prospectively measured SES in childhood in relation to adult sleep.

Keywords: Sleep, socioeconomic status, race, longitudinal

Sleep health is multidimensional and includes sleep duration, continuity, timing, perceived sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness (1). For the first time in five decades of public health priorities set by the U.S. Government, sleep health is in its 2020 plans. Specifically the 2020 Healthy People goal is to “increase public knowledge of how adequate sleep improves health, productivity, wellness, quality of life, and safety on roads and in the workplace” (2). The report also notes that poor sleep health is a common problem, with 25 percent of U.S. adults reporting insufficient sleep or rest at least 15 out of every 30 days.

Socioeconomic status (SES), defined by indices of access to resources and relative prestige, is considered to be one of the key contextual factors that contribute to disparities in sleep health (3). This assertion makes sense, given that SES impacts a number of factors that may impact dimensions of sleep health. For example, adverse health behaviors, including smoking, excessive alcohol, and lack of exercise, are more common among individuals from lower SES backgrounds and may impact sleep duration, continuity, and quality (4–6). SES is correlated with depressive symptoms (7). Sleep complaints often precede onset of depression, although some data suggest that the relationship may be bidirectional (8–10). Shift work affects sleep timing and may be associated with some low SES occupations (11;12). Furthermore, low SES environments may be more crowded, noisy, and less temperature-regulated, all of which can impact sleep. Finally, SES effects on sleep may reflect in part that SES tends to be lower in Blacks. As a group Blacks have shorter sleep and more evidence of sleep disordered breathing, whereas Whites have more or similar levels of sleep complaints and insomnia symptoms (see reviews by (13–16)). Thus, understanding the impact of SES must consider the racial/ethnic make-up of the study sample.

The evidence on associations of SES and sleep health primarily comes from cross-sectional survey studies. In general, lower SES is related to concurrent self-reported sleep disturbances and insomnia symptoms, with some evidence showing a relationship to very short or long sleep (17–20). Relatively few studies have examined SES in relation to other dimensions of sleep health, especially as assessed by objective measures. In a study of black and white middle-aged adults enrolled in CARDIA, those with lower income had longer sleep latency and poorer sleep efficiency as assessed by actigraphy, with associations stronger for blacks than whites (21). Among women enrolled in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) sleep study, reports of financial strain were associated with longer sleep latency and more minutes awake after sleep onset (WASO), but not with sleep duration (22). Similarly, a composite measure of SES based on education and income was related to greater PSG-assessed WASO but not to sleep duration in Black and White middle aged adults (23). Taken together, cross-sectional evidence suggests that low SES is related to perceived low sleep quality and may be related to objective indices of sleep continuity in adulthood, with possible differences due to ethnicity.

The association between lower SES and worse adult sleep characteristics may emerge early in the life span. Children from lower income families have shorter sleep duration and worse efficiency measured by actigraphy and more sleep problems than those raised in higher income families (24). Lower SES is associated with actigraphy-assessed shorter sleep duration during the school week and more variability in sleep onset among young adolescents (25). Retrospective reports of lower parental education are related to more sleep time in stage 2 and less time in slow wave sleep but are unrelated to total sleep time or WASO in Black and White adults (26). However, no longitudinal data are available about whether lower SES earlier in childhood precedes poor sleep in adulthood.

The primary objectives of the present report are to evaluate (a) whether family SES in childhood measured annually is related longitudinally to sleep duration and continuity measured by actigraphy, and perceived sleep quality measured by diary across one week in men; (b) whether the relationships differ between Blacks and Whites; and (c) whether the associations are independent of concurrent adult SES. Parents of the men in the present study reported annually their parental occupation and education when the men were ages 7 through 16. Thus, not only initial family SES but also change in family SES from ages 7 through 16 could be evaluated. Our primary hypotheses are that men who grew up in lower SES families and experienced declines or smaller increases in family SES in childhood through adolescence would have worse sleep as adults. We did not anticipate any differences by race. A secondary objective is to evaluate whether the SES associations remain significant adjusting for concurrent health behaviors, depressive symptoms, shift work, and other factors that may correlate with sleep health. The study contributes to the existing literature in a number of unique ways: its longitudinal design; repeated assessment of SES from childhood to adulthood; measurement of health behaviors reported daily and concurrent with the actigraphy measures; and inclusion of both Black and White men from a population-based urban sample.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were recruited from the youngest cohort of the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS; (27)), a longitudinal study of 503 boys initially recruited from Pittsburgh Public Schools in 1987–1988 when they were in the first grade. 849 boys were randomly chosen to undergo a multi-informant (i.e., parent, teacher, child report) screening that assessed early behavior problems, with half the sample from the top 30% of the screening measure scores, and the rest randomly selected from the remainder, hereafter called early behavior problem group. The boys’ mean age at screening was 6.9, and racial composition was predominately White (40.6%) and Black (55.7%). Nearly all primary caregivers were biological mothers (92%), with 45.3% cohabiting with a partner and 16.9% completing less than 12 years of schooling. Over half of families (61.3%) were receiving public financial assistance (e.g., food stamps).

In adulthood (mean age = 32 years; range 30–34 years), PYS participants were contacted to participate in a study examining early developmental factors associated with risk for cardiovascular disease (see Figure 1 for diagram of men in sleep study analytic sample beginning with the 503 boys who were enrolled in PYS). Eligibility criteria were still enrolled in PYS; not mentally disabled; not incarcerated; and alive. Of the 395 eligible men, 312 (79%) participated in some or all of the protocol. Of the 312, those who were in the Pittsburgh vicinity or planning on returning to Pittsburgh for holidays were invited to participate in the sleep study, provided that they were not being treated for apnea; 267 enrolled in the sleep study. Of the 267, data from 23 men were not included, usually because of lost or malfunctioning equipment (see Figure 1 for specifics). The analytic sample of 244 men did not differ from the 259 nonparticipants on race, early behavior problem group, SES, sleep or number of health problems reported by parents at study entry, ps>0.22 (See supplement Table 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh, and all men provided written, informed consent.

Figure 1.

Diagram of participant recruitment into sleep analysis group.

Overview of the protocol

Upon arrival at the University, they signed consent IRB forms, fasting blood draw was taken, and anthropometrics were measured. After resting for 10 minutes, they performed a series of challenging tasks while cardiovascular measures were taken, answered questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics, health history, health behaviors, stress and personal characteristics. At the conclusion of the laboratory portion, those who reported they did not have apnea were invited to wear an actigraph and to complete daily diaries for a week. When they completed the study, they were paid for their time and were provided a personalized set of information regarding their sleep characteristics.

Sleep measures

The Mini-mitter actiwatch model AW-16 (Philips Respironics, Bend, OR) was used to collect sleep/wake activity continuously over seven days and nights. Men were instructed to wear the watch on the non-dominant arm and to press an event marker when they tried to go to sleep. Actiwatches were configured to collect data during 1-minute epochs. Stored data were downloaded into the Actiware software program (version 5.57) for processing and analysis. The medium threshold (default) was selected to detect sleep periods of at least 3 hours in duration based upon sleep onset and offset using the 10-minute criterion of quiescence, i.e., less 40 activity counts. Sleep duration was calculated as actual sleep time from initial sleep onset to final sleep offset based on the actigraph records, excluding periods of wakefulness throughout the sleep interval. WASO was the total number of minutes between initial sleep onset and final sleep offset that were spent awake. Sleep quality was assessed in their diary after awakening on a 5 point scale from very poor sleep quality (0) to very good sleep quality (4) and averaged across study period; these data were available for 225 men. The distribution of WASO had a kurtosis of 1.398, so it was square root transformed, which improved the kurtosis to .165; sleep duration and quality were normally distributed. The three sleep measures – duration, WASO, and quality -- were not correlated with one another in the full sample or within blacks and whites separately.

Socioeconomic status

There are a number of ways SES can be measured (28). The PYS adopted the Hollingshead system that is based on occupational prestige and education of parents and/or caregivers (29). This measure is used widely in research on SES and health, although other more detailed methods are available. At the time when the boys were interviewed between the ages of 7 and 16 years, the parents or primary caretakers (who lived with them if the boys were not living with their biological parents) were asked annually about the occupation and educational attainment of the parents or primary caretakers. These were coded by the same PYS study data manager over all years into one of the 9 Hollingshead occupational prestige categories (ranging from 1, e.g., menial labor to 9, e.g., higher executive, major professional) and 7 educational categories (ranging from 1, i.e., less than 7th grade to 7, graduate/professional training) and summed after weighting the occupation category relatively more, as is standard. New occupations that were not on the original list developed by Hollingshead were categorized by the data manager following group meetings to develop consensus on appropriate categories. For those currently unemployed, the job code from the prior annual visit was used. If the child was from a 2 parent family, the higher Hollingshead score was used. Scores could range from 3 to 66, with higher scores indicating higher SES; the range in our sample was 6 to 63. Changes in family SES from ages 7 to 16 years of age were primarily driven by changes in occupational prestige categories rather than education categories as occupational prestige changed within our sample to a greater degree (correlations of occupational prestige codes among the years ranged from .34 to .68 with an average correlation of .53) than did education categories (correlations among the years ranged from .65 to .88 with an average correlation of .75).

For the present study, we adopted the same method for assessing SES in adulthood to allow comparability over time between childhood and adult SES. The men were asked for their current occupation, full-time/part-time status, and highest years of education and degree. The occupation of men not currently working and receiving unemployment compensation was based on the occupation reported at the last study visit, approximately 3 years earlier (as was used in earlier assessments within PYS). If unemployed and not having a prior occupation recorded at the last assessment, and receiving public assistance, child support, or income from illegal activities, the participant was given the lowest occupation status. As in prior years of PYS, the Hollingshead scoring system was used to code occupation and education of the men. We also recorded the number of individuals living in the household and whether or not there were children under the age of two in the household.

Potential covariates. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Recent Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (short form; 30) that was used throughout the PYS. This questionnaire containing 13 items that were rated on a 3 point scale, not true (0), sometimes true (1), and true (2). Sample items are “You felt miserable or unhappy” and “you felt like a bad person”. The total score is correlated with the scores from the Children’s Depression Inventory and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children depression scale, and discriminated clinically referred psychiatric patients from pediatric controls (30). Confirmatory factor analysis shows a unidimensional factor structure across grades 1 – 10 in a large sample of boys; factor loadings increased with age, suggesting the depression construct was measured with less error as the children matured (31).

When the participants were 7-years- old, their caregivers completed the child behavior checklist (CBCL) indicating whether the behavior was “not true” of their son, “somewhat true”, and “very true” (32). Included in the checklist were ratings for trouble sleeping, nightmares, sleeps less than most children, and sleeps more than most children during the day and/or night. In a study of children and adolescents, CBCL ratings by parents of less sleep and more trouble sleeping were correlated significantly but modestly with shorter sleep time by polysomnography and with diary ratings by children of sleep quality (33). Principal component analysis of the 4 items revealed two factors: trouble sleeping and less sleep than others, eigenvalue = 1.35; and nightmares and sleep more than others, eigenvalue = 1.05. We averaged the pairs of ratings at age 7 and used them as potential covariates.

The diary completed prior to bedtime asked if participants had during that day exercised, smoked cigarettes, used illegal drugs (including marijuana), and drank alcohol. All answers were yes/no. The proportion of days during the sleep study that they engaged in these behaviors was calculated. As part of a detailed medical interview, participants reported current medications. With consultation with a sleep medicine physician, medications were coded into yes/no medications that could affect sleep; note that only 2 men indicated they were taking medications for sleep problems and the other “sleep” medications were largely psychotropic medications and sedatives. Men reported if they were a night shift worker (working between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m.) and day sleeper (defined as sleeping after 5 a.m.) and were categorized as yes/no. These reports were corroborated by reports in their daily sleep diaries; note that night shift workers did not work every night of the study period (actual nights worked ranged from 1–6, mean = 3.44). Night shift workers and day sleepers were retained in the sample to preserve the integrity of the school-based community sampling, with the exception of 2 night shift workers with extremely late wake-up times. Height, weight, and waist and hip circumference were measured in the laboratory by a trained staff member.

Statistical analysis

Sample and sleep characteristics were compared by race using t-tests and chi squares. To assess the relationships of SES in childhood and adolescence, we used unconditional growth models to estimate the nature of change in family SES over time using maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) within M-plus (version 7.3, Muthen & Muthen, (34)). MLE estimates within-individual change using all available data rather than resorting to list-wise deletion. MLE provides unbiased parameter estimates under the assumption that missing observations are missing at random. Intercept (i.e., SES age 7) and slope (from 7 to 16) factor variances were freely estimated (vs. fixed) in order to model individual variability in initial family SES and rates of change in SES over time. A linear model fit was good: comparative fit index (CFI) = .941, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .078, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .047. Missing family SES data at each annual visit ranged from 1.2% to 6.6%; tests for the impact of missingness using the Missing Value Analysis function in SPSS showed negligible effects.

Using SAS (version 9.4), linear regression analyses were conducted predicting the three sleep variables, with the initial model addressing whether the intercept and slope of SES over childhood and adolescence were related to the outcome, adjusted for race and early behavior problem group, followed by further adjustment of adult SES. Then models were evaluated adjusting for the key covariates, day sleeper, night shift worker and other covariates associated with sleep characteristics, ps < .10. The final step tested the interactions of race and family SES slope and intercept. Significant interactions were followed by analyses stratified by race. Sensitivity analyses excluding day sleepers were conducted and showed the same pattern of results as reported below.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

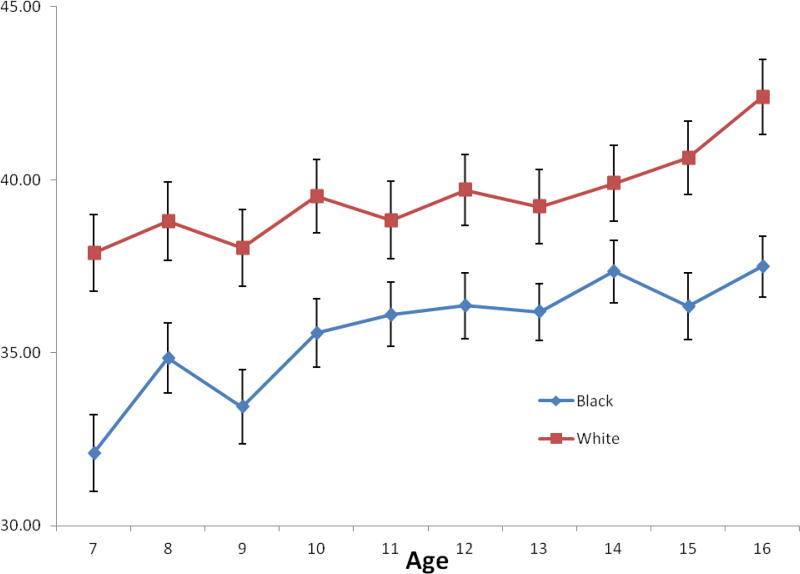

In general participants were middle- to lower-SES, with Whites reporting higher SES in adulthood and their families reporting higher at age 7 and 16. There was an increase in family SES over time, with no differences in change in SES between age 7 and 16 between Black and White participants. Figure 2 illustrates the mean SES scores across the ages; note that these scores are not the same as the intercepts and slopes calculated by M-plus but are included to provide the reader a sense of the raw data. On average the group was overweight (Table 1). More Whites than Blacks were taking medications that affect sleep. During the study protocol, Blacks reported in their diary proportionately more days that they drank alcohol and used illegal drugs than Whites, but they reported a similar proportion of days that they smoked or exercised. Participants on the whole were short sleepers, with 3.3% getting more than 8 hours of sleep and 25% getting less than 5 hours of sleep. Blacks had less sleep during their major sleep interval and across 24 hours than Whites (Table 2). Blacks also had higher WASO but reported similar sleep quality in their morning diaries.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted mean and standard deviations of family Hollingshead scores from ages 7 to 16 of Black and White participants. Higher scores reflect higher SES based on combination of education and occupational status. Note that these values are not the same as the estimated intercepts and slopes used in the analyses.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Mean (SD) or N (%).

| Black N=139 |

White N=105 |

Total N=244 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Hollingshead score *** | 28.14 (13.8) | 34.10 (14.5) | 30.73 (14.4) |

| Family Hollingshead score: | |||

| At Age 7 *** | 32.10 (13.1) | 37.88 (11.3) | 34.60 (12.7) |

| At Age 16 *** | 37.49 (10.1) | 42.40 (10.7) | 39.60 (10.6) |

| Difference between age | |||

| 7 and 16 | 5.36 (13.7) | 4.31 (10.4) | 4.91 (12.3) |

| Age (years) * | 32.24 (1.0) | 31.99 (0.9) | 32.13 (1.0) |

| BMI m2/kg | 29.63 (7.4) | 28.96 (6.5) | 29.34 (7.0) |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.92 (0.1) | 0.92 (0.1) | 0.92 (0.1) |

| Medications affecting sleep, yes * | 14 (10.1) | 23 (21.9) | 37 (15.2) |

| Current depressive symptoms | 4.51 (4.6) | 4.25 (4.4) | 4.40 (4.5) |

| Proportion days during sleep study: | |||

| Smoked | 0.53 (0.5) | 0.50 (0.5) | 0.52 (0.5) |

| Exercised | 0.23 (0.3) | 0.19 (0.3) | 0.22 (0.3) |

| Drank alcohol ** | 0.35 (0.3) | 0.23 (0.3) | 0.30 (0.3) |

| Used illegal drugs *** | 0.33 (0.4) | 0.09 (0.2) | 0.23 (0.4) |

| Daysleeper, N yes | 9 (6.5) | 9 (8.6) | 18 (7.4) |

| Night Shift Worker, N yes | 5 (3.6) | 4 (3.8) | 9 (3.7) |

| Early behavior problem group, N Positive | 73 (52.5) | 48 (45.7) | 121 (59.6) |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 race differences from t-tests and chi squares.

Table 2.

Sleep Characteristics

| Black (N=139) | White (N=105) | Total (N=244) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) major sleep duration in hours *** | 5.46 (1.1) | 6.29 (1.2) | 5.82 (1.2) |

| N (%) | |||

| <5hr | 46 (33.3) | 15 (14.3) | 61 (25.1) |

| 5 – 5.99 hr | 48 (34.8) | 23 (21.9) | 71 (29.2) |

| 6 – 6.99 hr | 35 (35.4) | 42 (40.0) | 77 (31.7) |

| 7 – 7.99 hr | 8 (5.8) | 18 (17.1) | 26 (10.7) |

| 8hr + *** | 1 (0.7) | 7 (6.7) | 8 (3.3) |

| Mean (SD) 24 hour sleep duration in hours *** | 6.02 (1.1) | 6.87 (1.4) | 6.38 (1.3) |

| N (%) | |||

| <5hr | 22 (15.8) | 7 (6.7) | 29 (11.9) |

| 5 – 5.99 hr | 54 (38.8) | 18 (17.1) | 72 (29.5) |

| 6 – 6.99 hr | 39 (28.1) | 39 (37.1) | 78 (32.0) |

| 7 – 7.99 hr | 18 (12.9) | 24 (22.9) | 42 (17.2) |

| 8hr + *** | 6 (4.3) | 17 (16.2) | 23 (9.4) |

| Mean (SD) awake after sleep onset in minutes* | 68.40 (27.6) | 61.20 (24.0) | 65.30 (26.3) |

| Median (IQR) * | 65.43 (30.6) | 58.00 (30.3) | 61.14 (29.9) |

| Mean (SD) Perceived sleep quality | 2.28 (0.7) | 2.21 (0.5) | 2.25 (0.6) |

| Less Sleep/Trouble Sleeping at age 7 | 0.11 (0.28) | 0.13 (0.30) | 0.12 (0.29) |

| Sleep More/Nightmares at age 7 | 0.22 (0.31) | 0.15 (0.29) | 0.19 (0.31) |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 race differences from t-tests.

Note perceived sleep quality based on 225 men.

Concurrent associations of adult measures and sleep characteristics

Shorter sleep duration was associated with not taking medications affecting sleep, a greater proportion of days drinking alcohol, and being a night shift worker during the sleep study (Table 3). There were trends for shorter sleepers to report more depressive symptom and being a day sleeper, ps = .07. Greater WASO was associated with a greater proportion of days using illegal drugs, a smaller proportion of days exercising during the sleep study, and lower concurrent SES, with trends for associations with depressive symptoms and not being a night shift worker, ps = .07. Lower sleep quality reported in the daily diary was associated with more depressive symptoms and being a day sleeper, with trends for being a night shift worker, p = .07, and taking medications that impact sleep, p = .09.

Table 3.

Univariate correlations between sleep measures and other variables.

| Sleep Duration | Wake After Sleep Onset |

Perceived Sleep Quality |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hollingshead scores | .01 | −.24**** | .04 |

| BMI | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Waist/hip ratio | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Medications affecting sleep | 0.18*** | 0.01 | −0.12* |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.12* | 0.12* | −0.35**** |

| Proportion days during sleep study: | |||

| smoked | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.03 |

| exercised | −0.08 | −0.15** | 0.01 |

| drank alcohol | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| used illegal drugs | −0.10 | 0.16** | −0.06 |

| Daysleeper (yes =1) | −0.12* | 0.00 | −0.16** |

| Night Shift Worker (yes =1) | −0.18*** | −0.12* | −0.12* |

| Less Sleep/Trouble Sleeping at age 7 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| Sleep More/Nightmares at age 7 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| Early behavior problem group (Positive=1) | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

p < .10,

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Note that correlations for perceived quality were based on data from 223 to 225 men, whereas the correlations for duration and wake after sleep onset were based on 242 to 245 men.

None of the adult sleep measures were associated with the child CBCL sleep scores.

Longitudinal associations of childhood and adult SES and sleep measures

Sleep duration

Longer sleep duration was associated with being White and was not associated with any of the childhood or adult SES measures, ps> .15. Test for interaction of childhood SES measures and race was significant for race by SES slope, b = .48 (.14), p <.001, but not for race by SES intercept, p = .42. Models stratified by race showed null effects for any SES measures in Blacks for sleep duration, ps >.29. In Whites, shorter sleep duration was associated with increasing slopes, b = −.97 (.28), p = .001, independent of the childhood SES intercept and adult SES, and other covariates (see Table 4). We repeated the analyses testing for curvilinear associations between SES and sleep duration, but they were nonsignificant in the full sample, ps > .38, or in whites separately, ps > .83. We then examined whether the intercepts and slopes among whites were related to bedtime or wake time as recorded in their diaries. Results showed that neither intercepts nor slopes of SES were related to timing measures, ps > .28. Because the associations for Whites were unexpected, we examined a few potential explanations relevant to household composition, i.e., number of individuals in the household, and whether there were any children under the age of 2, postulating that smaller families and those without young children would be more conducive to longer sleep and be associated with increasing family SES in childhood. However, these analyses did not change the results (data not shown).

Table 4.

Regression coefficients (SE) from multiple regression analyses of sleep duration (hours) for Whites (N=105)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early behavior problem group | −0.02 (0.22) | −0.13 (0.23) | −0.19 (0.22) |

| Childhood SES: | |||

| Intercept | −0.03 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) |

| Slope | −1.03 (0.28)*** | −0.94 (0.28)** | −0.97 (0.28)*** |

| Adult SES | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | |

| Covariates: | |||

| Sleep medications | -- | -- | 0.56 (0.27)* |

| Depressive symptoms | -- | -- | −0.19 (0.10) |

| Alcohol | -- | -- | −0.03 (0.37) |

| Daysleeper | -- | -- | −0.37 (0.41) |

| Night Shift Worker | -- | -- | −1.41 (0.59)* |

p<.05* p<.01** p<.001***

Wake after sleep onset

Greater WASO was associated with lower SES intercept and decreasing (or less increasing) slope (Table 5). Addition of adult SES to the model did not change the results for childhood SES; adult SES was also related to WASO. Significant covariates were not being a night shift worker and the greater proportion of days that men used illegal drugs and smaller proportion of days that they exercised during the sleep study week. Interactions between childhood SES intercept, p = .80 and slope, p = .99, with race were nonsignificant. Collinearity diagnostics of tolerance, variance inflation factor, and condition did not reveal significant multicollinearity. To illustrate the associations between the SES indicators and WASO, we categorized men into quartiles of SES groups for each SES indicator separately and provide estimated mean WASO scores (adjusted for other covariates in the multivariate model 3) in Figure 3.

Table 5.

Regression coefficients (SE) from multiple regression analyses of wake after sleep onset in minutes (square root transformed)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 0.17 (0.10) | 0.12 (0.10) | 0.09 (0.11) |

| Early behavior problem group | 0.06 (0.20) | −0.05 (0.20) | −0.09 (0.20) |

| Childhood SES: | |||

| Intercept | −0.03 (0.01) * | −0.03 (0.01)* | −0.03 (0.01) * |

| Slope | −0.57 (0.22) * | −0.57 (0.22)* | −0.67 (0.22) ** |

| Adult SES | -- | −0.02 (0.01) ** | −0.02 (0.01) * |

| Covariates: | |||

| Depressive symptoms | -- | -- | 0.05 (0.09) |

| Exercised | -- | -- | −1.00 (0.34) ** |

| Used illegal drugs | -- | -- | 0.63 (0.28) * |

| Daysleeper | -- | -- | 0.22 (0.44) |

| Night Shift Worker | -- | -- | −1.45 (0.60) * |

p<.05* p<.01** p<.001*** Ns for models were 244, 242, and 240 men for models 1 to 3 respectively.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the associations of mean estimated Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO) in minutes based on multivariate model 3 based according to quartiles of the distributions of scores for intercepts, slopes, and adult Hollingshead scores. Quartile 1 represents the lowest SES and quartile 4 represents the highest SES. Panel A is WASO mean estimates by quartile of intercepts (based on SES at approximately 7); Panel B is WASO mean estimates by quartile of slopes (based on SES from ages 7 to 16); and Panel C is WASO mean estimates by quartile of adult SES (based at approximately age 32). Covariates in model 3 were early behavior problem group, depressive symptoms, proportion days exercised, proportion of days used illegal drugs, daysleeper, and nightshift worker.

Perceived sleep quality

Perceived sleep quality rated in the diary was unrelated to SES in childhood or adulthood. There were no significant interactions of childhood SES slope, p = .64, or intercept with race, p > .33 (data not shown). Only greater depressive symptoms were related to poor sleep quality in the full multivariate model, b = −.19 (.04), p <. 001.

DISCUSSION

The primary finding of the present study was that a measure of sleep (dis)continuity, WASO, was greater among men who were from lower SES families at study entry when they were about seven- years- old, had less improvement in family SES from seven until 16 years of age, and were currently lower in SES as adults. Multivariate analyses showed that impact of SES from childhood to adulthood on WASO was independent of race, depressive symptoms, medications affecting sleep, being a night shift worker or day sleeper, and concurrent measures of health behaviors. These findings are by and large consistent with the cross-sectional associations in adulthood of SES and measures of sleep continuity. New is the long-term impact of lower SES in childhood and adolescence on adult sleep continuity.

Unexpectedly, white men who increased in family SES from childhood through adolescence had shorter sleep as adults. Most cross-sectional studies do not find an association between lower SES and objective measures of shorter sleep duration in adulthood; the present study also did not find a concurrent association of adult SES and sleep duration. The effect in white men is not due to the covariates that differed by race, i.e., sleep medication use and proportion of days taking illegal drugs or drinking alcohol. We explored several other possible structural factors, i.e., family size, number of young children in the home, but these further analyses were not illuminating. We believe that SES may have had an inconsequential impact on Black men’s sleep duration, in part because their sleep duration is quite short. However, we do not have a ready explanation for the impact of change in family SES across childhood through adolescence for White men.

A number of interesting associations were obtained between concurrently measured health behaviors and sleep characteristics. Reporting fewer days of any exercise and more days of drinking any alcohol and illegal drug use were associated with concurrent sleep measures across the week. While these associations have been obtained in other samples, the unique aspects are the method of assessment via daily diary concurrent with the sleep measures and the sample of men initially recruited from an urban inner city school district. From a prevention perspective, better sleep would be encouraged with more regular exercise and less use of alcohol and illegal drugs on a daily basis.

The study was not designed to identify which aspects of low SES families and environments were particularly likely to mediate the relationships with sleep continuity. Because the analyses adjusted for some of the proposed candidates, the analysis ruled out current shift work or sleeping primarily during the day, health behaviors, and depressive symptoms as primary determinants of sleep continuity in relation to SES. Other environmental features, such as noisy, excessive cold or hot sleep environment, crowded housing, air pollution, may play a role but were not measured. Regularity of life style in general may vary by SES and more unpredictable schedules may impact sleep characteristics. Accumulation of stressors during childhood and adolescence that are correlated with low SES may have residual influences on adult sleep. These are important topics for future investigation.

Part of the interest in investigating disparities in sleep health associated with SES stems from a desire to understand why low SES leads to poor health (3;17;35). Although substantial evidence indicates the importance of sleep duration in understanding health disparities, it may be a more important determinant in Blacks, who characteristically have shorter sleep. Our data and other evidence indicate that short sleep duration is less likely to be consistently associated with low SES and in consequence may not be the key sleep characteristic for understanding health disparities associated with SES. Our and other data suggest that sleep continuity may be the key healthy sleep characteristic, beyond sleep disorders, to consider in the context of mediating SES-health relationships.

The study had several limitations. First, the findings cannot be generalized to women, older populations, or ethnic groups other than Blacks and Whites. Second, the study did not measure sleep disordered breathing and relied on participant report. Those who reported being treated or diagnosed with sleep disordered breathing were not included in the sleep study. The study design oversampled boys with early behavior problems s; however, inclusion of group status did not impact the findings. Finally, although participants were comparable on specific characteristics to those not in the sleep analysis, there was the potential for bias due to attrition. Men who participated in the interview and questionnaire aspects of the protocol but not the clinic protocol tended to live more than 75 miles from Pittsburgh (data not shown). On the other hand, the study has several positive features, its longitudinal assessment of SES using the same measure throughout the study; week-long assessment of sleep using actigraphy and diary; and a population-based sample of Black and White men drawn from a large urban school district area.

In conclusion, the present study finds that SES is associated with sleep continuity in adult men, with independent associations of family SES at age 7, change in family SES from 7 through 16, and mid-life adult SES. Unexpectedly, Whites who increased in SES across childhood and adolescence had shorter sleep. To our knowledge this is the first evidence of the association of childhood SES measured prospectively rather than retrospectively on sleep characteristics in mid-life men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by HL111802.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014 Jan;37(1):9–17. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. [10-4-2016];2016 Ref Type: Online Source. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, Jean-Louis G. Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med. 2016 Feb;18:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Chen E, Matthews KA. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Feb;1186:37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dworak M, Wiater A, Alfer D, Stephan E, Hollmann W, Struder HK. Increased slow wave sleep and reduced stage 2 sleep in children depending on exercise intensity. Sleep Med. 2008 Mar;9(3):266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao MN, Blackwell T, Redline S, Stefanick ML, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL. Association between sleep architecture and measures of body composition. Sleep. 2009 Apr;32(4):483–90. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull. 2003 Jan;129(1):10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep. 2013 Jul 1;36(7):1059–68. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2014 Dec;18(6):521–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008 Apr;31(4):473–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harma M, Tenkanen L, Sjoblom T, Alikoski T, Heinsalmi P. Combined effects of shift work and life-style on the prevalence of insomnia, sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998 Aug;24(4):300–7. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilcher JJ, Lambert BJ, Huffcutt AI. Differential effects of permanent and rotating shifts on self-report sleep length: a meta-analytic review. Sleep. 2000 Mar 15;23(2):155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adenekan B, Pandey A, McKenzie S, Zizi F, Casimir GJ, Jean-Louis G. Sleep in America: role of racial/ethnic differences. Sleep Med Rev. 2013 Aug;17(4):255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrov ME, Lichstein KL. Differences in sleep between black and white adults: an update and future directions. Sleep Med. 2016 Feb;18:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiter ME, Decoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Sleep disorders in African Americans and Caucasian Americans: a meta-analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8(4):246–59. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2010.509251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiter ME, Decoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Normal sleep in African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2011 Mar;12(3):209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandner MA, Petrov ME, Rattanaumpawan P, Jackson N, Platt A, Patel NP. Sleep symptoms, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013 Sep 15;9(9):897–905. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lallukka T, Arber S, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Complaints of insomnia among midlife employed people: the contribution of childhood and present socioeconomic circumstances. Sleep Med. 2010 Oct;11(9):828–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE. Short sleep duration across income, education, and race/ethnic groups: population prevalence and growing disparities during 34 years of follow-up. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;17(12):948–55. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Grandner MA. Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep. 2014 Mar 1;37(3):601–11. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, et al. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Jul 1;164(1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: The SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2009;32(1):73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, et al. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Psychosom Med. 2008 May;70(4):410–6. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M, Keller PS, Kelly RJ. Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children's sleep and cognitive functioning: the moderating role of parent education. Child Dev. 2009 May;80(3):875–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marco CA, Wolfson AR, Sparling M, Azuaje A. Family socioeconomic status and sleep patterns of young adolescents. Behav Sleep Med. 2011 Dec 28;10(1):70–80. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.636298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomfohr LM, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Childhood socioeconomic status and race are associated with adult sleep. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8(4):219–30. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2010.509236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeber R, Farrington D, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Raskin White H. Violence and serious threat: Development and prediction from childhood to adulthood. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International journal of methods in psychiatric research. 1995;(5):237–49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messer SC, Angold A, Costello EJ, oeber R, van Kammen W, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents: Factor composition adn structure across development. Int J Meth Psychiatric Res. 1995;5:251–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregory AM, Cousins JC, Forbes EE, et al. Sleep items in the child behavior checklist: a comparison with sleep diaries, actigraphy, and polysomnography. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 May;50(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mplus [computer program] 1998–2012 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:501–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.