Abstract

Background

Transgender/non-binary (trans/NB) individuals face major challenges, including within healthcare.

Objectives

Transform Health Arkansas (THA) engaged trans/NB Arkansans in defining their greatest health-related concerns to inform responsive, partnered, participatory research.

Methods

The THA partnership engaged trans/NB individuals through an interactive, trans/NB-led process in nine summits across the state and collected surveys on research interests. Descriptive analysis examined respondent characteristics by gender identity, mode of survey completion, and most pressing concerns.

Results

The summits, attended by 54 trans/NB and 29 cisgender individuals, received positive evaluations. The top five priorities among 140 survey respondents included: 1) transition-related insurance coverage, 2) access to transition care, 3) education of healthcare providers, 4) public education, and 5) supportive healthcare systems. The THA has also led to trans/NB individuals educating a range of audiences about transgender issues.

Conclusions

Next steps include dissemination, identification of evidence-based interventions addressing prioritized issues, and joint development of a research agenda.

INTRODUCTION

Transgender/non-binary (trans/NB) (Table 1) individuals face major challenges, including within healthcare. Discrimination in healthcare settings and provider lack of knowledge about transgender issues create unsafe environments, poor quality of care, underutilization of essential services, and limited access to transgender care.1–4 While advances in access to care due to the Affordable Care Act have increased health insurance coverage among trans/NB individuals, many of their health-related needs remain unmet. The extent of these challenges varies across the U.S., with greater disparities in rural areas and certain geographic regions, including the south.1, 3, 4

Table 1.

Definition of Terms

| • | Transgender is an adjective referring to those whose gender identity is different, at least some of the time, from the sex assigned to them at birth |

| • | Nonbinary is an adjective describing those whose gender identity is not limited to the gender binary, that is, for individuals who don’t identify as just female or just male. |

| • | Cisgender is an adjective used to describe individuals who identify their gender as the same as that assigned to them at birth. |

Trans/NB individuals may, of necessity, choose not to be out in order to maintain their safety, employment, housing, and personal relationships.3, 5 They may lack trust in cisgender (Table 1) researchers and providers and related institutions due to concerns about or actual experiences of harassment, abuse, exploitation, outing, ridicule, or other damaging encounters.3,5 Participatory research approaches with trans/NB individuals have succeeded in improving recruitment and retention, quality of information about lived experiences, and appropriateness of intervention designs.6–8 However, continued exploration is needed to better understand how participation can truly enhance empowerment and capacity.9

This paper reports on some of the efforts of a partnership between trans/NB individuals, researchers, providers, and transgender advocates in the rural, southern state of Arkansas. This partnership’s goal is to learn the most pressing health and healthcare concerns of trans/NB Arkansans to inform design and implementation of responsive, partnered, participatory research addressing barriers to trans/NB health.

BACKGROUND OF THE PARTNERSHIP

Organizational development

In February 2014, two transgender Arkansans established the Arkansas Transgender Equality Coalition (ArTEC) as a statewide, transgender-led organization to advance justice and inclusiveness for trans/NB Arkansans. ArTEC developed community relationships via a website and private Facebook group and through town-halls with the transgender community.

Early on, the transgender community indicated a need to prioritize their healthcare concerns. An online health survey of 84 trans/NB Arkansans conducted in 2013/2014 in collaboration with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health (COPH) found 33% reported postponing either medically needed or preventive healthcare due to discrimination on the part of a healthcare provider; 19% had been refused treatment by a healthcare provider; and 39% reported having to teach their medical provider about trans/NB people to receive appropriate care.10

Consistent with these concerns, ArTEC’s current director began an online resource directory listing Arkansas healthcare and mental health providers identified by trans/NB individuals as “trans-friendly.” ArTEC maintains this resource on their website with continued input from trans/NB individuals who have experienced the services it contains.

Partnership development and operation

In 2012, faculty, staff, and students at UAMS partnered with the University of Arkansas at Little Rock to develop a Safe Zone program in support of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (LGBTQ) individuals within their institutions.11 LGBTQ individuals, including ArTEC members, served as Safe Zone trainers and ArTEC members began serving as guest presenters on transgender issues in UAMS courses. In May 2015, ArTEC partnered with faculty at the COPH to obtain a community engagement award from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). This “Pipeline to Proposals Tier One” award enabled ArTEC to engage trans/NB individuals across the state in defining their health-related research interests and priorities and form a Research Working Group (RWG) partnership comprising trans/NB individuals, researchers, providers, and advocacy organizational members. The original trans/NB members of the RWG were recruited by ArTEC’s trans leadership to achieve diverse representation of the trans/NB community. Academic and provider members were recruited primarily by COPH faculty though some were engaged by trans members based on their existing relationships. Once formed, the RWG jointly developed a partnership governance document describing the RWG’s purpose, membership, expectations, roles and responsibilities, meeting guidelines, and communication and decision- making processes. The RWG meets face-to-face monthly for one-and-a-half to two hours to network, share, and update each other on their activities, problem solve, develop plans, and make decisions. Non-local members join by skype and all members interact via a private google group between meetings.

Achieving diverse representation of trans/NB RWG members on the RWG has been a key challenge faced by the partnership. RWG has worked to identify and address barriers to engagement including moving the meetings to a more accessible location within the community, scheduling meetings in the evenings when more people are available, and providing transportation. Diversity and social committees have recently been formed to focus on more intentional inclusion efforts.

Herein we describe the group facilitation process the RWG partnership used to engage trans/NB Arkansans, share what was learned from the community, and detail some of the current and planned activities.

METHODS

Pre-Summit Activities

Promotion of Transform Health Arkansas Initiative (THAI)

In June 2015, ArTEC did a press release, provided information about the project through interviews with the press, and posted information on the private ArTEC Facebook page. The implementing team (ArTEC leadership and COPH partner) also conducted public information sessions and held regular potlucks to build relationships within the trans/NB community and with allies in central Arkansas. Working with the RWG, the team named the project “Transform Health Arkansas”, developed a logo and an interactive website, and used social media to communicate about the THAI. RWG members unable to attend in person due to travel barriers participated via Skype or conference calling.

Development and content of health concerns survey instrument

A key objective was to engage the trans/NB community in defining their most pressing health and healthcare concerns. RWG members developed a short instrument including selection of language, terms, and wording of questions led by the trans/NB members of the RWG with demographic questions and an open- ended question asking trans/NB individuals and allies to “list up to five transgender health or healthcare related issues you are the most concerned about and you would like this research group to focus on” (Appendix A). The instrument was pretested informally by members of the RWG with each other and friends and family and updated before finalizing. An information cover sheet stated the survey’s purpose, that it was voluntary and anonymous. A letter of determination regarding this survey about health concerns of the trans/NB community was submitted to the UAMS Institutional Review Board, which determined that this activity did not meet the definition of human subjects research.

Regional Summits

RWG members and partners organized a series of nine interactive regional summits to generate dialogue and build relationships with, and discuss the most pressing health concerns of, trans/NB Arkansans. The original project plan was to have at least one summit in each of Arkansas’s five main geographic regions, including central, northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast Arkansas. Lack of contacts in southeast Arkansas, a less populated region, caused the summit planned in this region to be relocated and then canceled when no trans/NB participants attended. Multiple sessions were held in the two regions (central and northwest) with the largest populations and most organized trans/NB communities in the state.

Recruitment to summits

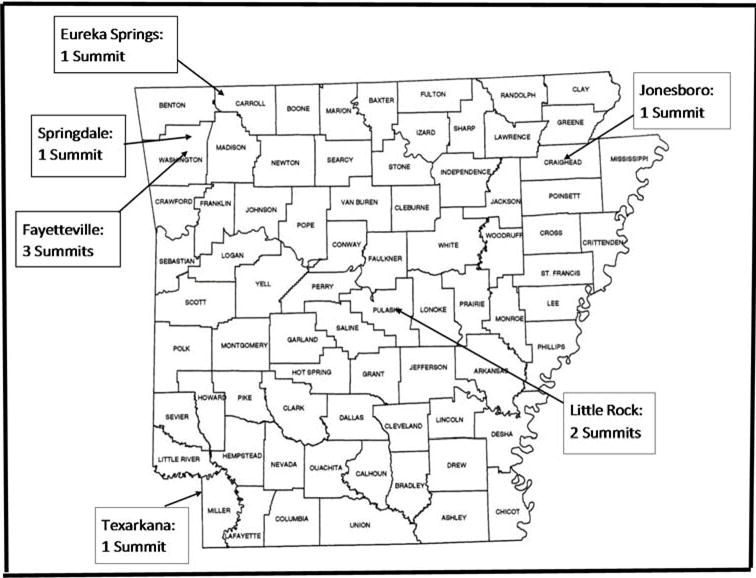

Several locations (Figure 1) with local trans/NB leaders were selected and information about the summits was shared through their networks, as well as through Facebook, email, the ArTEC website, LGBTQ organizations, PRIDE events, and word of mouth. Trans/NB individuals were encouraged to bring cisgender allies, including partners, healthcare providers, and other community members, to the summits to participate in a separate discussion and receive education about transgender health. Allies on the private ArTEC facebook also learned about the summit and were invited through that mechanism.

Figure 1.

Map of Summit Locations

Summit Description

The implementing team recruited local trans/NB individuals to serve as facilitators, provided them with training, a written facilitator’s guide (Appendix B) and summit materials developed by the RWG. Table 2 describes summit preparation activities and materials. At registration, volunteers greeted participants, asked them to complete their information on the sign in sheet, provided summit packets, nametags and a button to wear to indicate their personal pronouns. Food was served during registration.

Table 2.

Summit Preparation Activities

| • Secure a meeting place with two separate spaces that the local trans group considers neutral and safe |

| • Negotiate availability of at least one gender neutral bathroom |

| • Arrange for food |

| • Prepare summit packets1 and pronoun buttons2 |

| • Identify and orient volunteers to staff the table and provide assistance |

| • Set up registration table with packets and buttons and two separate meeting spaces |

Packets: agenda, resource list, THAI information sheet, index cards for stories exercise, post-it notes and round stickers for prioritizing exercise, health interest survey, a post-session evaluation.

Pronoun buttons: “he/him/his”, “she/her/hers”, “they/them/theirs”, “zie/zim/zir”, etc. show the importance of using the pronouns each individual wants others to use when talking about them. These buttons help us show respect in affirming each person’s identity.

The summit facilitator welcomed participants, introduced themselves and the THAI team members and volunteers, gave the location of gender neutral bathroom(s), and explained the purpose of designating gender neutral bathrooms for those unaware of the need. The facilitator then gave the project overview explaining the goal of the summits to obtain trans/NB individuals’ perceptions of the most pressing issues affecting their community. The facilitator also led a discussion with participants to develop a joint space agreement to establish expectations and get buy-in regarding how the meeting would be conducted and listed points (e.g. silence phones, avoid side conversations, respect all opinions, speak up but don’t dominate, maintain confidentiality, respect others’ privacy, etc.) on flip chart pages for each room. They also explained that much of the discussion would be conducted separately for trans/NB individuals and allies to assure trans/NB participants had the freedom to express themselves openly and honestly without having to worry about offending cisgender allies and providers and without bias or pressure that might influence their discussion. The decision to have separate sessions was made by trans/NB RWG members and summit facilitators.

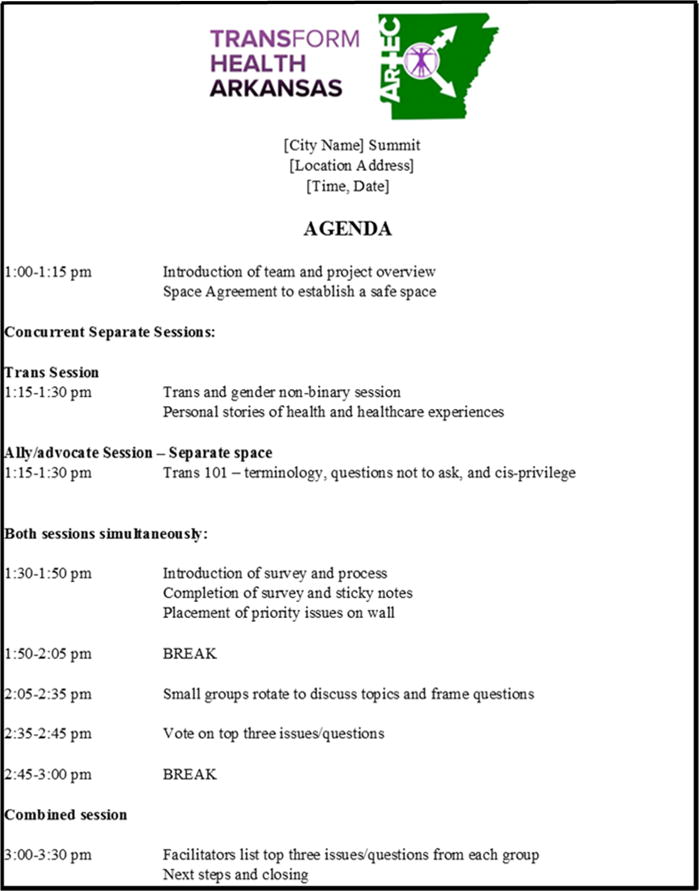

Figure 2 illustrates the agenda for the concurrent sessions. Volunteers were available to assist with mobility, literacy, writing, vision, or other limitations and answer questions, re-explain tasks, and help as needed. The trans/NB session began with a story-telling exercise to get participants thinking about their health concerns. Facilitators asked participants to write about a positive and/or negative healthcare experience on a large post-it note and place on a wall around the room. Participants were then asked to select one story that especially resonated with them, and volunteers shared the reason for their selection. In the ally session, a transgender facilitator provided a brief orientation to trans/NB terminology, discussed questions not to ask trans/NB people, and introduced examples of cisgender privilege.

Figure 2.

Transform Health Arkansas – Regional Summit Sample Agenda

After these introductory exercises, facilitators explained the purpose, content, and anonymous, voluntary nature of the survey about the health and healthcare concerns related to the trans/NB community before asking participants to complete it. Next, participants wrote each of their top three concerns from the survey on different colored post-it notes and stuck them on the wall according to rank. Then a 15-minute break was given.

During the break, facilitators reviewed the notes, grouped them into overarching topics (e.g. insurance coverage for transition care), and placed them on the wall at stations around the room labeled with the topics. After the break, participants divided into small groups and rotated through the stations to discuss the topics and write relevant questions they would like to see studied on the large flip chart pages.

After the question generating session, facilitators asked participants to rotate through the room to review each question and vote to rank their top three priority questions for study using three round, colored stickers in their packets (3 points for red, 2 points for yellow, and 1 point for green). Facilitators counted up the votes and listed the five highest ranking topics in the trans/NB and ally groups. Trans/NB and cisgender ally participants then came together to review and compare each list. During the joint closing session, facilitators from each group presented their results and opened a discussion to request feedback from participants about the topics and process used to identify priorities. Prior to closing, facilitators thanked participants and asked them to complete the post-summit evaluation (Appendix C.). Both trans/NB and cisgender ally participants were encouraged to network with other participants at the end of each summit.

Additional Data Collection

Due to concerns that the sample did not capture the diversity of the trans/NB population in Arkansas and to allow for input from individuals who were unable to attend a summit, surveys were administered in other formats and settings. Specifically, surveys were distributed online through a link posted on the THAI page of the ArTEC website and on ArTEC’s Facebook page and sent through email, and on paper through personal contacts made by trans/NB individuals, advocates, and providers. The opportunity to complete the survey was promoted through the ArTEC webpage, through personal contacts, at trans/NB/ally potlucks, and through social media.

Trans/NB summit participants were asked to write on a sticky note about one or more of their healthcare experiences. Since this exercise was primarily intended to engage participants in the topic of the summit, the notes were not processed to use as data for this paper. However, because the healthcare issues prioritized persistently pervade our ongoing work we have many accounts of trans/NB individuals’ experiences that illustrate these issues. To provide this context we have documented, with permission, some of these stories in anonymous quotes.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Analysis

The open-ended survey responses on top priority health/healthcare issues were analyzed using conventional content analysis12 to identify major themes. Two of the researchers (MKA and MKS) independently read through all of the open-ended survey responses related to high priority health and healthcare concerns several times to identify themes emerging from the data. These two researchers compared the initial themes they identified in their independent review and agreed upon ten themes captured in the data. One of the senior researchers (MKS) created a code book and definition sheet of the ten identified themes. Using this code book and set of defined themes, she coded the responses from all participants. A third researcher (SAM) then reviewed and coded all of the responses independently using the same code book and set of defined themes. These two researchers (MKS & SAM) then compared the similarities and differences between their independently coded data. Discussion and deliberation over each of the codes occurred until each of their disagreements in coding were resolved for all of the responses. One of the initial researchers (MKA) reviewed and confirmed the coding generated from this process. Then, all of the coded responses were counted using SPSS to identify the five most reported themes overall and disaggregated for trans/NB and cisgender allies. The researchers performed member checks with trans/NB members of the RWG by sharing the identified themes and confirming that the themes resonated with our community partners.

After identifying the themes, top ranking questions generated at the summits related to each of the top five themes were collected and presented with each theme.

Quantitative Analysis

Data from pre-coded responses, combined with coded, open-ended data, were analyzed by a trans member of the research team using SPSS to describe the respondent sample and produce descriptive statistics. Because of the diversity of ways that transgender individuals describe their gender, it is challenging to create categories that capture everyone. However, for the purposes of this analysis, transgender was defined as anyone whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth. Non-binary gender was defined as trans participant whose gender identity was not exclusively man, woman, trans man, or trans woman were analyzed. Differences in respondent characteristics and most commonly reported themes are reported by source of data (i.e. collected through a summit, online, or through personal contacts.)

RESULTS

Survey Respondent Demographics

In total, nine summits were held throughout the state (Figure 1) between July 2015 and April 2016, and 54 trans/NB and 29 cisgender allies participated. Table 3 shows respondent characteristics including gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship status, ethnicity, race, age, health insurance status, education, employment status, gross annual income, and veteran status for trans/NB individuals and cisgender allies who participated in the summits. Roughly one third each of all trans/NB participants reported being a man and/or transman (31%); a woman and/or a trans woman (36%); or a gender included under non-binary as described above (32%). The most common sexual orientation reported was bisexual/pansexual/queer (46%) followed by heterosexual (20%). Twenty percent of trans/NB participants were non-white and 8% were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. Forty percent had incomes of $20,000 or less and 50% did not have a degree beyond high school. Only 5 of the 22 under age 22 were under 18 (not shown) and only 4 were 65 years or older.

Table 3.

Demographic Variables based on Gender Identity and Completion Method for Participants with Complete Responses

| Cisgender Ally Participants | Trans/NB Participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summit, Paper, or Online n (%) |

Summit n (%) |

Paper Elsewhere n (%) |

Online n (%) |

Total n (%) |

||

| Total | 29 (100%) | 54 (65.06%) | 19 (22.89%) | 23 (27.71%) | 96 (100%) | |

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Man/Trans man | 12 (41.38%) | 18 (33.33%) | 2 (10.53%) | 10 (43.48%) | 30 (31.25%) | |

| Woman/Trans woman | 17 (58.62%) | 18 (33.33%) | 12 (63.16%) | 5 (21.74%) | 35 (36.46%) | |

| Non-binary | N/A | 18 (33.33%) | 5 (26.32%) | 8 (34.78%) | 31 (32.29%) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 14 (48.28%) | 10 (18.52%) | 4 (21.05%) | 5 (21.74%) | 19 (19.79%) | |

| Gay/Lesbian | 5 (17.24%) | 6 (11.11%) | 2 (10.53%) | 6 (26.09%) | 14 (14.58%) | |

| Bisexual/Pansexual/Queer | 8 (27.59%) | 28 (51.85%) | 8 (42.11%) | 8 (34.78%) | 44 (45.83%) | |

| Asexual/Other | – | 8 (14.81%) | 3 (15.79%) | 1 (4.35%) | 12 (12.50%) | |

| Questioning/Prefer not to say | 2 (6.90%) | 2 (3.70%) | 2 (10.53%) | 3 (13.04%) | 7 (7.29%) | |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single | 5 (17.23%) | 24 (44.44%) | 9 (47.37%) | 10 (43.48%) | 43 (44.80%) | |

| Partnered | 11 (37.93%) | 18 (33.33%) | 8 (42.11%) | 8 (34.78%) | 34 (35.42%) | |

| Married/Civil Union | 11 (37.93%) | 5 (9.26%) | 1 (5.26%) | 3 (13.04%) | 9 (9.38%) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 2 (6.90%) | 7 (12.96%) | 1 (5.26%) | 2 (8.70%) | 10 (10.42%) | |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (6.90%) | 5 (9.26%) | 3 (15.79%) | – | 8 (8.33%) | |

| No | 27 (93.10%) | 49 (90.74%) | 16 (84.21%) | 23 (100%) | 88 (91.67%) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 22 (75.86%) | 43 (79.63%) | 13 (68.42%) | 21 (91.30%) | 77 (80.21%) | |

| Racial Minority | 7 (24.14%) | 11 (20.37%) | 6 (31.58%) | 2 (8.70%) | 19 (19.79%) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 13–21 | 2 (6.90%) | 10 (18.52%) | 5 (26.31%) | 5 (21.74%) | 20 (20.83%) | |

| 22–29 | 6 (20.69%) | 18 (33.33%) | 8 (42.11%) | 6 (26.09%) | 32 (33.33%) | |

| 30–39 | 3 (10.34%) | 10 (18.52%) | 2 (10.53%) | 5 (21.74%) | 17 (17.71%) | |

| 40–64 | 11 (37.93%) | 15 (27.78%) | 3 (15.79%) | 5 (21.74%) | 23 (23.96%) | |

| 65+ | 7 (24.14%) | 1 (1.85%) | 1 (5.26%) | 2 (8.70%) | 4 (4.17%) | |

| Have health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (93.10%) | 51 (94.44%) | 14 (73.68%) | 18 (78.26%) | 83 (86.46%) | |

| No | 2 (6.90%) | 3 (5.56%) | 5 (26.32%) | 5 (21.74%) | 13 (13.54%) | |

| Highest educational degree | ||||||

| High school or equivalent | 6 (20.69%) | 24 (44.44%) | 14 (73.68%) | 10 (43.48%) | 48 (50.00%) | |

| Associate’s degree | 2 (6.90%) | 11 (20.37%) | 1 (5.26%) | 5 (21.74%) | 17 (17.71%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 (24.15%) | 14 (25.93%) | 1 (5.26%) | 6 (26.09%) | 21 (21.88%) | |

| Graduate degree | 14 (48.28%) | 5 (9.26%) | 3 (15.79%) | 2 (8.70%) | 10 (10.42%) | |

| Currently enrolled student | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (17.24%) | 18 (33.33%) | 4 (21.05%) | 5 (21.74%) | 27 (28.13%) | |

| No | 24 (82.76%) | 36 (66.67%) | 15 (78.95%) | 18 (78.26%) | 69 (71.88%) | |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed/self-employed | 21 (72.41%) | 41 (75.93%) | 12 (63.16%) | 13 (56.52%) | 66 (68.75%) | |

| Unemployed | 8 (27.59%) | 13 (24.07%) | 7 (36.84%) | 10 (43.48%) | 30 (31.25%) | |

| Gross annual household income | ||||||

| Less than $10,000 | 1 (3.45%) | 6 (11.11%) | 5 (26.32%) | 6 (26.09%) | 17 (17.71%) | |

| $10,001–$20,000 | 4 (13.79%) | 13 (24.07%) | 5 (26.32%) | 3 (13.04%) | 21 (21.88%) | |

| $20,001–$35,000 | 1 (3.45%) | 14 (25.93%) | 3 (15.79%) | 4 (17.39%) | 22 (22.92%) | |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 5 (17.24%) | 9 (16.67%) | 2 (10.53%) | 3 (13.04%) | 14 (14.58%) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 4 (13.79%) | 6 (11.11%) | 4 (21.05%) | 2 (8.70%) | 12 (12.50%) | |

| Greater than $75,000 | 11 (37.93%) | 2 (3.70%) | – | 3 (13.04%) | 5 (5.21%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (10.34%) | 4 (7.41%) | – | 2 (8.70%) | 6 (6.25%) | |

| Veteran | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (13.79%) | 8 (14.81%) | 3 (15.79%) | 3 (13.04%) | 14 (14.58%) | |

| No | 25 (86.21%) | 46 (85.19%) | 16 (84.21%) | 20 (86.96%) | 82 (85.42%) | |

Demographic variables for trans/NB survey respondents based on other participation methods (paper and online) are also presented in Table 3. Inclusion of online and personal contact surveys allowed for an additional 42 trans/NB respondents. Although the online survey was less successful at recruiting racial minority trans/NB participants than the summits (8.70% compared with 20.37%), distributing by hand through personal contacts allowed for more participation from this demographic (31.58%). Alternative distribution also resulted in more participants who were unemployed, had lower educational attainment, and living in extreme poverty (less than $10,000 gross annual household income). Additionally, a total of 15 respondents were recruited online or through personal contacts from 11 counties that did not have participants at one of the summits. It is important to note, however, that only 19% of survey respondents who did not participate in a summit listed a total of the five requested health/healthcare concerns, compared with 45% of summit participants. Therefore, although inclusion of additional completion methods allowed for engagement of more difficult to reach segments of the trans/NB population, surveys were more complete when respondents participated in a summit.

Health and Healthcare Concerns

Table 4 lists the main themes identified through the content analysis of the open-ended responses related to the most pressing health and healthcare concerns as well as examples of survey responses that generated these themes. The five health and healthcare concerns reported most frequently were: 1) insurance coverage for transition-related care, 2) access to/availability of transition-related care, 3) education of healthcare providers about trans/NB patients and issues, 4) public education to address stigma and discrimination and non- healthcare systems change, and 5) healthcare systems and policies that are supportive and trans/NB-inclusive. Table 5 shows percentages of trans/NB respondents whose responses reflected each of these top five themes for both summit participants and nonparticipants. Illustrative quotes from trans/NB individuals about experiences they have had related to the top three themes prioritized in the summits are shown in Table 6. Table 7 presents the highest ranking questions that were generated at summits related to the top five issues.

Table 4.

Main themes and examples from responses on most pressing health/ healthcare concerns

| Themes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Insurance Coverage for Transition-related Care | “Trans-inclusive insurance coverage” “Lack of inclusive insurance coverage” “Lack of insurance coverage for all of my transition related healthcare” |

| Access to / Availability of Transition-Related Care | “Support/help/access in rural and isolated communities” “Access to sex positive, trans positive sex ed and healthcare.” “Access to hormones.” “Access to gender affirming surgeries.” |

| Education of Healthcare Providers about trans/NB patients and issues | “Doctors and medical staff that are fully informed on transgender related health issues” “Many health providers are not educated in transgender issues” “Doctors and nursing and other staff being educated about being respectful to trans folks.” “Education among healthcare workers relating to how trans bodies and minds work.” “Lack of trans health curriculum in nursing / pre-med programs (includes medical / law schools)” |

| Public Education to Address Stigma and Discrimination and Non-Healthcare Systems Change | “Better exposure of information and transgender services to the public” “Religious…education. We’re not all going to hell, you know.” “Public education including parents.” |

| Healthcare Systems and Policies that are Supportive and Trans/NB-Inclusive | “Options on paperwork for more than physical sex and biological/legal name including preferred name, preferred pronouns, and gender identity, etc.” “Allowed to use preferred gender and name on official documentation.” “Rights a person has in a hospital.” “Medical records having the preferred name on them.” |

| Access to Trans/NB-Knowledgeable Mental Health Care Providers | “Finding a supporting/properly trained mental health care [provider].” “Mental health services geared to or with knowledge of transgender identities” “Mental Health–affordable, competent counseling resources to use in order to further the transitioning process.” |

| Concerns for Transgender/Non-Binary/Gender Non-Conforming Youth | “Support and access for trans youth” “Access for pre-puberty treatment.” “Youth counseling” |

| Physical Health Concerns | “Help with hair removal for MtF patients” “Current public health data/implications for prevention of STIs among transgender persons” “Interactions of ART and HRT.” “HIV in the transgender community” “Sexual assault” “What comorbidities may affect ability to medically transition? (i.e., does diabetes contraindicate HRT?)” |

| Suicide and Suicide Prevention | “Psychologist and support for suicidal issues, depression” “Suicide rate and altogether safety of trans folks.” |

| Homelessness | “Homeless Transgender Youth” “How do we reach the homeless population” |

Table 5.

Top 5 healthcare concerns for trans/NB respondents who did and did not attend a summit

| Participated in Summit n (%) |

Online/Paper Elsewhere n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Priority | Concern | 1st Priority | Concern | |

| Insurance | 26 (48.15%) | 41 (75.93%) | 14 (33.33%) | 18 (42.86%) |

| Access | 14 (25.93%) | 40 (74.07%) | 10 (23.81%) | 17 (40.48%) |

| Provider Education | 13 (24.07%) | 41 (75.93%) | 4 (9.52%) | 8 (19.05%) |

| Public Education | 8 (14.81%) | 30 (55.56%) | 5 (11.90%) | 8 (19.05%) |

| Supportive Systems | 9 (16.67%) | 26 (48.15%) | 3 (7.14%) | 4 (9.52%) |

Table 6.

Illustrative Quotes about Three Healthcare Issues Most Prioritized in Summits

| Insurance coverage for therapy and trans-related care: | |

| • | “My insurance denied coverage of my therapy because of my gender dysphoria. Fortunately, my hormones are covered because of the way my doctor codes it, but coverage for my surgery was denied. I saved and paid for that myself.” (Trans man in his 30’s) |

| • | “Even with Medicare [which is supposed to cover it], I’ve had issues with getting coverage for HRT. I had issues with gatekeeping by an endocrinologist who wanted a referral from a psychiatrist instead of a therapist. He also wanted me to pay despite Medicare covering the procedure, because he didn’t believe Medicare would pay for it. The second doctor I went to didn’t give me any referral issues but did ask me to pay. The doctor I finally went to was backed up but didn’t need a referral and was able to bill Medicare.” (Trans woman in her 50’s on disability) |

| • | “I was denied coverage for hormones until my gender marker was changed and I still can’t get mental health care through [my insurance provider] because they pay so poorly none of the few available gender affirming therapists will take it.” (Trans woman in her 40s) |

| Availability of providers willing to provide/capable of providing transition care: | |

| • | “I waited for 10 years to transition because I didn’t know of anyone who would prescribe hormones. I finally found a therapist who knew [doctor who provides HRT] and was able to start on T.” (Trans man in his 30’s) |

| • | “I bounced from therapist to therapist just to get a letter to get hormones. I eventually went to [a trans clinic out of state 5 hours away] to get hormones.” (Trans man in his 30s) |

| • | “It took me five different attempts after months and months to get an appointment with a therapist [to talk about my gender dysphoria]. There was no psychotherapist in my [small rural town] so I finally went to the [community mental health center] in [larger town]. When I put “gender dysphoria” on the paperwork, the office staff just said ‘Well you aren’t going to get help with that around here’ and they didn’t refer me to another provider.” (Trans woman in her 40’s) |

| Need for provider sensitivity/education/cultural competency: | |

| • | “I waited three months for an appointment with a highly regarded eye specialist for treatment of an ongoing serious eye condition. When the doctor saw me, he said he wasn’t going to treat me and told me to ‘get out of’ his practice. I drove 10 hours from [rural hometown], only to be dismissed by this specialist.” (Trans woman in her 40’s) |

| • | “Doctors often ask about my transition when it’s totally unrelated to the care I need from them that day. They ask me in all kinds of ways. ‘Where are you in your transition?’ ‘Have you had all your surgeries?’ It’s like they’re saying ‘Reassure me that you are who you say you are or I won’t believe you’re really a man.” (Trans man in his 30’s) |

| • | “I’ve spent a lot of time in the mental healthcare system starting at the age of 12 after attempting suicide. I was in residential care in a religiously affiliated facility where the staff were openly homophobic and transphobic, and I was treated poorly. I was a patient there multiple times over a span of years. They justified their ineffectual and often damaging treatment by noting that their religious beliefs mandated it.” (Trans man in his 20’s) |

| • | “When I went to the emergency room for a suicide attempt they put the wrong gender (F) on my arm band even though I had already legally changed my name and gender with my insurance. When I tried to get her to fix it the clerk rolled her eyes and blew me off. Then, when I told the doctor I had gender dysphoria he said, ‘I don’t know how to deal with this’ and made notes and left the room. Later when I was institutionalized in [mental healthcare facility] they kept me in their lobby area for what seemed like hours, then finally moved me to a room in the female wing. When I pitched a fit, they pulled me aside and asked about my genitals. They finally put me in a room by myself. Then later, when another trans guy was being admitted they actually talked about his personal information with me, which was a HIPAA violation, and ended up putting us in a room together. They also called my partner and talked about me using my deadname.” (Trans man in his 20’s) |

| • | “I had the doctor in the emergency room say ‘shame on you!’ for not telling them I’m trans. I didn’t tell them when I was admitted because I didn’t think it had anything to do with the problem I was there for and I was afraid of how I would be treated. I didn’t think it was medically necessary to tell them. His attitude certainly didn’t help.” (Trans man in his 30’s) |

| • | “I’m not out yet in [small rural hometown] and I can’t go to a dentist locally because they all want to see your med list which would “out” my status/identity.” (Trans woman in her 40’s) |

Table 7.

Top Ranking Questions from Summits for Top 5 Issues

| INSURANCE COVERAGE FOR TRANSITION RELATED CARE | |

| • | What steps need to be taken to acquire proper healthcare through insurance policy change? |

| • | How do we establish concise and fair insurance policies for trans individuals? |

| • | How can we mandate transition related care to be covered by employers/insurance companies across the nation? |

| ACCESS TO / AVAILABILITY OF TRANSITION CARE | |

| • | How can we improve access [to trans care] for low income people? |

| • | How do we improve access to services in isolated and rural communities? |

| • | EDUCATION OF HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS ABOUT TRANS/NB PATIENTS/ISSUES |

| • | How can we improve the sense of safety for patients seeking medical care? |

| • | Best ways to train providers to provide HRT in areas with little access to services? |

| • | How do we influence schools/specifically nursing or medical programs to include transhealth curriculum? |

| • | How do we get textbooks in the education system to include trans issues so patients don’t have to teach providers? |

| • | How do we get a LGBTQIA focused clinic/medical facility for general specified treatment in our area? |

| • | What existing methodologies have [been] shown successful in increasing provider competence? |

| • | How important is it for trans people to be involved in conducting training? |

| • | How can we foster more understanding towards non-binary people, especially those desiring physical transition? |

| PUBLIC EDUCATION TO ADDRESS STIGMA AND DISCRIMINATION AND NON-HEALTHCARE SYSTEM CHANGE | |

| • | How do we educate legal and judicial community to not let personal bias keep them from upholding the law? (eg. Judges grilling you over name changes) |

| • | What are the best methods for educating the general public regarding trans-related issues and trans people? |

| • | How do we educate first responders and law enforcement to respectfully deal with trans people in crisis? |

| HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS CHANGE | |

| • | How to remove gender marker from insurance to ensure care for all trans patients’ needs? (i.e. Trans man needing gynecology exam and having male marker on insurance) |

Summit Evaluation

Fifty-five attendees completed summit evaluations. For the question regarding to what extent respondents felt comfortable and safe to participate, the weighted average on a scale from 1 to 5 was 4.64, with 1 being “not at all comfortable” and 5 being “totally comfortable”. Similarly, the weighted average was 4.65 for the question “To what extent do you feel your opinions were heard and incorporated?” Some of the main themes in the open-ended responses to the question, “What did you like best about the summit?” mentioned the inclusive nature of the event, that trans/NB voices were heard, that separate spaces were made available to assure their safety, and the opportunity to learn about trans/NB issues (Appendix D).

DISCUSSION

The work described herein elicited rich information about issues that must be addressed to improve health and quality of life for trans/NB Arkansans and has resulted in an important network of trans/NB individuals, providers, advocates, and researchers that continues to grow and build capacity for future action.

Summit participants were more likely to provide a total of five health issues, but non-summit participants were on average lower income, more rural, and had less formal education. In particular, those engaged through personal contacts were more racially diverse as well. These findings suggest that although the summit process allowed for better survey completion and dialogue, it was not the most successful method for reaching harder to engage portions of the trans/NB community. At the same time, all three groups gave similar priority to the five issues that ranked highest overall. In addition, summit participants gave very positive evaluations of their experiences with this engagement approach.

Each of the healthcare-related issues prioritized in our survey could be positively affected by the May 13, 2016 issuance of the final Section 1557 Rule for the ACA which interprets Section 1557’s sex nondiscrimination protections to include explicit protections for transgender individuals on the basis of gender identity. This rule required health plans to include provisions for not discriminating on the basis of gender identity effective January 1, 2017.13

Limitations

Only five of our survey respondents were minors; thus this group and their concerns are underrepresented by our results. Likewise, we were not able to identify local partners in the southeast region of the state, which is more rural and has a higher percentage of African Americans. These shortcomings of our efforts are particularly concerning because of the high risk of depression, anxiety, violence against, and suicidality among unsupported trans/NB youth,14 and the overlapping, intersectional oppression that can occur for racial minorities identifying as transgender.1 We are working to increase our engagement of these groups by engaging new providers for young trans/NB individuals, using our personal contacts to reach trans/NB people of color, and establishing the RWG diversity committee.

Local successes, current activities and plans

A number of positive outcomes have resulted locally from this work including: recruitment of trans/NB patients from UAMS to serve as advisors to the Emergency Department through service on their Patient and Family Advisory Council; achievement at UAMS of LGBTQ Leadership status based on the national Healthcare Equality Index benchmarking tool;15 recruitment of new providers to provide transition-related care; human resources support for UAMS’s first employee transitioning on the job; and establishment of a trans/NB education working group to increase public and professional understanding of trans/NB people and present results of the Transform Health survey. These changes have resulted from relationships developed between RWG members and in an effort to address problems identified in meetings and through the summits and other surveys. The education working group formed to address the priority identified by participants to improve public and professional understanding of trans/NB people, but also to have the capacity for trans/NB individuals to proactively respond to requests for education about transgender issues. Trans/NB members of this education group have given such presentations for UAMS nursing students, graduate social work students, faith groups, the annual conferences of the Arkansas Community Health Workers Association and the Arkansas Society for Public Health Education, the executive Leadership team for Patient and Family Centered Care at UAMS, and UAMS’ Cancer Institute grand rounds.

The THAI RWG is currently implementing phase two of this work with Tier II PCORI funding, holding summits and using social media to disseminate our results, and incorporating community feedback. We are redoubling our efforts to engage more trans/NB people of color and developing a national network of trans/NB and academic partners. We will also identify evidence based interventions addressing the issues identified in Tier I and jointly develop a comparative effectiveness research question to pursue for future grant funding.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the consistent efforts of the Transform Health Arkansas Research Working Group, which has guided and supported this work in countless ways. We also want to thank all of the members of the Arkansas trans/NB community and their allies who attended summits or otherwise shared their perspectives with us by completing the survey of research interests and telling their stories. This work was supported through a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pipeline to Proposals Tier I award (Project Number: 3414216) and was also partially supported by the Arkansas Center for Minority Health Disparities: A National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Exploratory Center of Excellence through a grant provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NIMHD (Grant Award ID: 5 P20 MD002329) and by the Translational Research Institute, grant UL1TR000039 through the NIH National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of PCORI or NIH.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

Introduction

TRANSform Health Arkansas is administering this Health Research Interest Survey to gain information about the healthcare and health-related research interests of the Arkansas transgender, gender non-conforming, non-binary population, and their allies and providers. Survey participants will remain anonymous and privacy will be protected.

In order to complete the survey a participant must be 13 years or older, currently living in Arkansas and should identify as transgender, gender non-conforming, non-binary, or as an ally or provider for this population. For purposes of this survey, we define transgender/gender non-conforming/non-binary as people whose gender identity or expression is different, at least part of the time, from the sex assigned to them at birth.

We will use the information gathered in this survey to develop a health research agenda with the transgender, gender non-conforming, and non-binary population of Arkansas with a goal of transforming their health and healthcare.

Invitation to Participate

We are inviting you to complete this survey if you are at least 13 years old, live in Arkansas, and identify as either transgender, gender non-conforming, non-binary, or are an ally or provider for this population.

Confidentiality

You are not being asked to provide your name or other personally identifying information and your responses to the survey will remain confidential. No one will be able to identify your individual answers.

Voluntary

Your participation in this survey is voluntary. If you decide to participate, you do not have to answer any questions on the survey that you do not wish to answer and you can choose to withdraw your responses at any time before you submit your answers. You will not suffer any negative consequences if you refuse to complete this survey.

By completing the survey, your informed consent to participate is implied.

If you have questions about this survey or about the Transform Health Arkansas project, please contact:

Andrea Zekis: [emai]; [phone] or

Kate Stewart: [email]: [phone]

□ Please check this box if you have read and understood the information above and wish to complete the survey.

Date: ___________________________

The following questions ask about your socio-demographic characteristics to help us determine whether we are reaching a diverse group of individuals with this survey.

Please answer BOTH questions about Hispanic origin and race.

- Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?

-

□Yes

-

□No

-

□

- What is your race? Mark all items that apply.

-

□White

-

□Black or African American

-

□American Indian or Alaska Native

-

□Asian or Pacific Islander

-

□Arab or Middle Eastern

-

□Multi-racial

-

□Other (specify) _____________________

-

□

- What is your age group?

-

□13–17 years

-

□18–21 years

-

□22–29 years

-

□30–39 years

-

□40–49 years

-

□50–64 years

-

□65–74 years

-

□75 or older

-

□

What is the county in AR where you live? _________________________________

- Do you identify as trans?

-

□Yes

-

□No

-

□

- What is the biological sex you were assigned at birth?

-

□Female

-

□Male

-

□Intersex assigned female

-

□Intersex assigned male

-

□

- What is your current gender identity? Mark all that apply.

-

□Female

-

□Male

-

□Intersex

-

□M to F/Transwoman

-

□F to M/Transman

-

□Genderqueer

-

□Genderfluid

-

□Gender non-conforming

-

□Non-binary

-

□Agender/genderless

-

□Neutrois

-

□Polygender

-

□Other (please specify) ______________

-

□

- What is your sexual orientation?

-

□Heterosexual

-

□Gay

-

□Lesbian

-

□Bisexual

-

□Pansexual

-

□Asexual

-

□Queer

-

□Questioning

-

□Prefer not to say

-

□Other (please specify) ____________________________

-

□

- Do you have health insurance?

-

□Yes

-

□No

-

□

- What is the highest educational degree you have received?

-

□None

-

□Elementary school diploma

-

□Middle school diploma

-

□High school diploma or the equivalent (GED)

-

□Associate’s degree

-

□Bachelor’s degree

-

□Master’s degree

-

□Professional degree (MD, DDS, JD, etc.)

-

□Doctorate degree (PhD, DrPH, EdD)

-

□

- What is your gross annual household income level?

-

□Less than $10,000

-

□$10,001-$20,000

-

□$20,001-$35,000

-

□$35,001-$50,000

-

□$50,001-$75,000

-

□$75,001-$100,000

-

□$100,001-$125,000

-

□$125,001-$150,000

-

□Greater than $150,000

-

□I don’t know

-

□

- What is your current work status?

-

□Employed

-

□Self-employed

-

□Un-employed

-

□

- Are you currently a student?

-

□Yes

-

□No

-

□

- What is your current relationship status?

-

□Single

-

□Partnered

-

□Civil union

-

□Married

-

□Separated

-

□Divorced

-

□Widowed

-

□Common law marriage

-

□

- Are you a veteran or active military?

-

□Yes, a veteran

-

□Yes, active military

-

□No

-

□

- Please list up to five transgender health or healthcare related issues you are the most concerned about and you would like this research group to focus on in order of their importance to you.

- 1. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 2. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 3. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 4. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 5. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

PLEASE DO NOT SUBMIT THIS SURVEY IF YOU HAVE ALREADY COMPLETED IT IN THE PAST.

Appendix B. Summit Facilitator’s Guide

FACILITATOR GUIDE

Registration: Volunteers should direct everyone to sign the contact sheet when they come in. After signing in, everyone will get a packet, and a nametag sticker. Packets will include the agenda, the project information sheet, the resource sheet, the survey, and post-session evaluation on the right side and on the left side there will be note paper sticky notes for the stories exercise, post-it notes for the issues exercise, and round stickers for the prioritizing exercise.

| 1:00–1:15 pm | Introduction of team and project overview |

Introduction of the team:

Welcome the participants and thank them all for coming and then introduce any members of the team, members of the Research Working Group, or any volunteers who are present to stand or wave and be recognized. Tell where the bathrooms are and if we have been able to create gender neutral bathrooms, tell the group about that and what that means.

Project Overview:

Give an overview of the project and tell the purpose of the summit in less than five minutes. Describe that the process for the day will be explained later but that we have designed it to be interactive and participatory to allow everyone to give their input. If there will be separate sessions, explain that wear are doing this to assure a safe space for the trans community members, while also emphasizing our appreciation for allies and advocates and providers who may have come to participate.

Space Agreement

Explain that we want to agree on what is needed to have a safe space for discussions. Start by listing some things we know we want included and ask the participants to add to the list. Facilitators or volunteers will write these on two separate sheets for the two rooms. The list needs to, at a minimum, include:

Silence phones. (Ask people to leave the space if they feel like they have to answer a call or text)

Stay present in the conversation – please no side conversation

Respect others’ opinions

Step up, step back (speak up but don’t dominate. If you have spoken already, allow others to talk.)

Maintain confidentiality

Respect others’ privacy.

When the overview and discussion of ground rules is complete ask the allies and advocates and others who do not identify as trans, gender non-conforming or non-binary to go to the separate room for their session.

Concurrent Sessions (Separate spaces):

| Trans Session | |

| 1:15 – 1:30 pm | Personal stories of health and healthcare experiences |

You have 15 minutes for this exercise.

Facilitator(s): Start off by welcoming everyone to the discussion and thanking them again for coming to the summit. Explain the stories exercise in your own words. Here are the steps:

Explain the purpose of the exercise – To get everyone thinking about health and healthcare issues that matter to the trans and non-binary community.

Give them a few minutes to think about their own health and healthcare experiences, both good and bad.

Ask them to find the notepaper sticky notes in their folders (have extras available just in case).

Tell them to write down one positive story/experience and one not so positive (maybe even terrible) experience – one on each of two pieces of notepaper. Tell them not to write their name.

After a few minutes, when it looks like most have finished, ask them to all go up to the wall and stick the positive stories on one side of the wall and the more negative story to the other side of the wall. If anyone has mobility limitations make sure someone assists them in getting their stories on the wall.

After all of the stories are posted, tell them to walk along the wall and read the notes. Ask them to pick one that especially speaks to them. If anyone has mobility limitations see if there’s a way to assist them in reading the notes on the wall.

Ask if anyone will volunteer to read one that especially spoke to them. If you have time, ask for several volunteers to read – including some who have chosen positive stories.

If you have time, after they read the story, ask them to say briefly why they chose it. • Adjust discussion based on the time left.

After a few have read (you may only have time for one positive and one negative), invite everyone to sit down again.

Ally/advocate Session (Separate space)

| 1:15–1:30 pm | Trans/NB 101 – terminology, questions not to ask, and cis-privilege |

We have 15 minutes for this exercise.

This will include a very brief trans/NB 101 discussion with the cis-group including terminology, questions not to ask, and what is cis-privilege.

Both sessions simultaneously:

| 1:30–1:50 pm | Introduction of survey and process |

| Completion of survey and sticky notes | |

| Placement of priority issues on wall |

You have 20 minutes to complete this exercise.

Explain the instructions using your own words. Here are the steps:

Introduce the survey and its purpose. The main goal of the summit today is to learn about the health and healthcare issues that are most important to the trans/ non-binary community.

Explain that we will be combining their input with that of others around the state who will be participating in similar summits.

We also have several questions about the personal characteristics on the survey. Explain why we are asking these questions. We want to be sure that we are getting responses from enough people that represent the whole community. This information allows us to see if we are reaching a diverse group of people. The survey is anonymous so we will not be able to link this information to any specific individuals.

Explain that the survey asks for everyone’s top five issues they would like to see studied. The issues can be personal but they don’t have to be. Think about the issues people raised on the cards if you are having a hard time thinking of something. (Facilitators need to avoid giving examples even when asked because we want to avoid priming them to focus on any one particular issue.)

After explaining the content, ask them to complete the survey.

When most have completed the survey, ask them to copy their top three issues from their list of issues (on the last page of the survey) on a different post-it note. Number 1 on Pink notes, Number 2 on Yellow notes, and Number 3 on Green notes.

After they have finished writing on the post-it notes, ask them to stand up and stick them to the wall according to the number of the issue as they have listed it. If anyone has mobility limitations make sure someone assists them in getting their notes on the wall.

Once they have stuck their notes to the wall, they can go on break for 15 minutes. Tell them what time to come back.

Ask them to turn in their surveys as they leave to go to the break.

| 1:50–2:00 pm | BREAK |

We have 10 minutes to do this.

While participants are taking a break, the facilitators will work with the Project Team to organize the issues into overarching topics and put them on flip chart pages around the room labeled by topics. Each page labeled with the overarching topic and its associated post-it notes will serve as a station. Put markers at each station and spread them out so small groups can congregate to discuss each one separately. Together you will determine how many small groups are needed to rotate through the stations – this is the number facilitators will have them number off to in order to form the small groups. (e.g. if there are 3 stations, ask them to number off from 1 to 3, etc.)

| 2:00–2:25 pm | Small groups rotate to discuss topics and frame questions |

You have 25 minutes to complete this exercise.

Explain the instructions in your own words. Here are the steps:

When they return, have them number off into as many small groups as there are topics at stations.

Assign them to starting stations and instruct each group to read the notes at their assigned station. After reading the notes together, they are to develop unanswered questions about the topic that they would like to see studied and write them on the flip chart paper.

You will have to allot an equal time for each group to spend at each station. Using a timer, have them rotate through all the stations over the course of the 30 minutes so that each group gets to discuss each of the overarching topics. We will try to have trained volunteers assigned to each of the stations so they can help to keep the discussion going and write the notes on the flip chart. This should help if anyone has literacy, writing, or vision limitations. Facilitators should float between groups to answer questions, reexplain the task, keep them on track, etc.

At the end of the exercise, invite all of them to take their seats.

| 2:25–2:40 pm | Vote on top three issues/questions |

You have 15 minutes to complete this exercise.

Here are the steps to explain:

Explain that this last step of the process will allow the whole group to prioritize across all of the topics and questions the group has come up with together. We want each person to vote on the three they want to rank as the highest priority.

Ask each person to take out the round circle stickers in their folders. Tell them to put the Red circle on their first priority issue, the Yellow circle on their second priority, and the Green circle on their third issue. Once they have selected their top three issues/questions, they can take a break.

Tell them to come back to the Trans/NB Session room at the end of the 15 minute break for a combined group wrap-up session.

Before they leave, ask them if anyone objects to leaving the notes on the wall for the other group of allies/advocates to see when they come in for the combined session. If anyone objects, take the flip charts off the wall and fold them for later recording.

| 2:40–2:45 pm | BREAK |

We have 5 minutes to do this. While the participants are on break the facilitators and project team will count up the votes on the topics and list the five that were ranked the highest in each of the two sessions (trans/NB and ally/advocate/provider).

Combined session – Trans/NB Room

| 2:45–3:00 pm | Facilitators list top three issues/questions from each group |

| Next steps and closing |

We should have 15 minutes left for this exercise.

We will welcome the combined group back to the closing session and again thank them for the great work they have done. Each of the facilitators from each session will report on the top five topics/questions that were identified by the two groups. After both groups have reported out we can hold a brief discussion of peoples’ thoughts and feedback and ask them to complete the evaluation. Before we close, we will describe next steps and let people know how they can stay involved, thank them for coming, and then close the session.

Appendix C. Post-Summit Evaluation Instrument

EVALUATION

Thank you for coming today. Your feedback will help us to improve our next summit.

- To what extent did you feel comfortable and safe to participate? (Circle number below)

1 2 3 4 5 Not at all Completely comfortable - To what extent do you feel your opinions were heard and incorporated? (Circle number below)

1 2 3 4 5 Not at all Totally - I felt that the amount of time allotted for the sessions in the summit was:

- Too much time for exercises, it was too long

- Too little time for exercises, it was too short

- Just right

What did you like the best about the summit? ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What could we do to improve future summits? ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

How did you hear about this event? _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

- 1.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. pp. 1–228. [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz TM. Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: a consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Soc Sci Med [Internet] 2014 Jun;110:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032. [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953614002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead J, Shaver J, Stephenson R. Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilization among rural LGBT populations. PLoS ONE. 2016 Jan 5; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146139. [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26731405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.R29 Editors. TransAmerica. How does your state rank on “the civil rights issue of our time”? 2015 Mar 9; [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: http://www.refinery29.com/2015/03/83531/transgender-rights-by-state.

- 5.Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1820–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796. [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780721/pdf/AJPH.2012.300796.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siskind RL, Andrasik M, Karuna ST, Broder GB, Collins C, Liu A, Lucas JP, Harper GW, Renzullo PO. Engaging transgender people in NIH-Funded HIV/AIDS clinical trials research. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016 Aug 15;72(Suppl 3):S243–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanner AE, Reboussin BA, Mann L, Ma A, Song E, Alonzo J, Rhodes SD. Factors influencing health care access perceptions and care-seeking behaviors of immigrant Latino sexual minority men and transgender individuals: baseline findings from the HOLA intervention study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014 Nov;25(4):1679–97. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun CJ, García M, Mann L, Alonzo J, Eng E, Rhodes SD. Latino sexual and gender identity minorities promoting sexual health within their social networks: process evaluation findings from a lay health advisor intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2015 May;16(3):329–37. doi: 10.1177/1524839914559777. Epub 2014 Nov 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guta A, Flicker S, Roche B. Governing through community allegiance: a qualitative examination of peer research in community-based participatory research. Crit Public Health. 2013 Dec;23(4):432–51. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2012.761675. Epub 2013 Jan 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coley C, Zekis A, Bellamy J, Stewart MK. “My PCP has virtually no idea how to treat transgender patients” Findings from a survey of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in Arkansas. Poster presentation at the American Public Health Association 143rd Annual Meeting; 2015 Nov; Chicago, IL.. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart MK, Allison K, Zekis A, Crutcher P, Sandusky M, Downs S, DeJohn T, Nelson R, Ballard A, Stacey T, Lieblong BJ. Development of a volunteer-led safe zone program at an academic health center and land-grant university in the South. Poster presentation at the American Public Health Association 143rd Annual Meeting; 2015 Nov; Chicago, IL.. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker K. LGBT Protections In Affordable Care Act Section 1557. 2016 Jun 26; [cited 2017 Jan 9] in Health Affairs Blog [Internet], about 1 screen. (place unknown) Copyright 1995 – 2017 by Project HOPE: The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc., eISSN 1544-5208 Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/06/06/lgbt-protections-in-affordable-care-act-section-1557/

- 14.Connolly M, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ, II, et al. The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health Epub. 2016 Aug 17;:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012. [cited 2016 Sept 5]. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com.libproxy.uams.edu/S1054139X1630146X/1-s2.0-S1054139X1630146X-main.pdf?_tid=faf9e2fe-73cd-11e6-96fa-00000aab0f27&acdnat=1473124099_6cb257aa9d95c0c700c4a44f5c0bd7f6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Human Rights Campaign. [Internet] Healthcare Equality Index. [cited 2017 Jan 9]. [about 1 page] Available from: http://www.hrc.org/hei.