Abstract

Cell-based therapy is an exciting, promising, and a developing new treatment for cardiac diseases. Stem cell–based therapies have the potential to fundamentally transform the treatment of ischemic cardiac injury and heart failure by achieving what would have been unthinkable only a few years ago—the Holy Grail of myocardial regeneration. Recent therapeutic approaches involve bone marrow (BM)-derived mono-nuclear cells and their subsets such as mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), endothelial progenitor cells as well as adipose tissue–derived MSCs, cardiac tissue–derived stem cells, and cell combinations. Clinical trials employing these cells have demonstrated that cellular therapy is feasible and safe. Regarding delivery methods, the safety of catheter-based, transendocardial and -epicardial stem cell injection has been established. However, the results, while variable, suggest rather modest clinical efficacy overall in both heart failure and ischemic heart disease, such as in acute myocardial infarction. Future studies will focus on determining the most efficacious cell type(s) and/or cell combinations and the most reasonable indications and optimal timing of transplantation, as well as the mechanisms underlying their therapeutic effects. We will review and summarize the clinical trial results to date. In addition, we discuss challenges and operational issues in cell processing for cardiac applications.

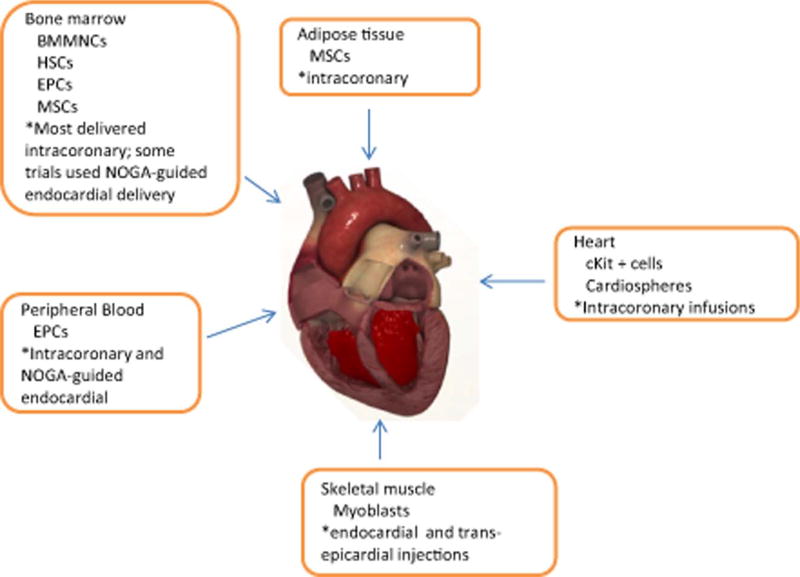

Heart failure (HF) due to ischemic injury, such as myocardial infarctions (MIs), contributes to 250,000 deaths annually with 500,000 new cases every year and an economic burden that exceeds $500 billion annually.1, 2 Current therapies seek to slow the progression to HF, but they do not stimulate regeneration to recover functional myocytes.2, 3 The endogenous regenerative capacity of the heart is inadequate to repair injured myocardium.4 Thus, stem cell therapy has emerged as a strategy aimed at preventing or reversing myocardial injury and promoting cardiac tissue regeneration. Preclinical models of ischemic heart disease and HF employing large animals have been instrumental in advancing phenotypic and mechanistic insights underlying stem cell therapy using different cell sources as well as the safety and efficacy of various methods of cell delivery modalities.5–11 The major cell types used have been skeletal myoblasts, unfractionated bone marrow (BM)–derived mononuclear cells (BMMNCs), and other BM- or blood-derived cells: mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), enriched CD34+ cells, and CD133+ cells. Other tissue-derived cells such as adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs), skeletal muscle–derived myoblasts, and more recently, cardiac-derived progenitor cells (cKit+ cells and cardiospheres) have also been used in clinical trials (Fig. 1). Approximately 2000 patients have been treated with unfractionated BMMNCs, which represent a greater number of patients than all other cell types combined.12 Thus far, three application routes have been used to transplant cells into the heart. The major route utilized has been direct intracoronary injection through an inflated over-the-wire balloon catheter.13 In addition, a few trials have utilized transendocardial or direct transepicardial injection.14, 15

Fig. 1.

Variety of cells from different sources and mechanism of delivery have been used in clinical trials for cardiac cell therapy. HSCs (i.e., CD34+) = hematopoietic stem cells

CELL TYPES AND ASSOCIATED CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Skeletal myoblasts expanded in culture from isolated satellite cell progenitors from a muscle biopsy were one of the first cells to be tested in clinical studies.16, 17 There have been a few randomized placebo-controlled studies evaluating the effect of injected skeletal myoblasts in patients with severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.16 There were no significant differences in cardiac function but in a substudy, it was found that patients treated with 800 million cells had a modest improvement in remodeling.16 A more recent Phase IIa randomized open-label trial (SEISMIC) using intramyocardial transplantation of myoblasts in HF patients did not show any improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) although there was improvement in 6-minute walk distance.18 A different double-blind randomized placebo-controlled multi-center study of intramuscular administration of myoblasts in HF (MARVEL) ended prematurely due to rising costs and occurrence of sustained ventricular tachycardias.19 Taken together, largely negative results and issues of arrhythmias make it unlikely that myoblast-based cardiac cell therapy will be further pursued.

The BM harbors a great variety of cell types such as hematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+ or CD133+), MSCs, EPCs, and more committed lineages that in turn are composed of yet poorly defined subsets. Injection of unfractionated, heterogeneous BMMNCs has been used in the greatest number of clinical trials (Table 1). These trials have shown that both intracoronary and intramuscular injection of BMMNCs is feasible and safe.20–24 To date the largest study of cardiac cell therapy is the Reinfusion of Enriched Progenitor Cells and Infarct Remodeling in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REPAIR-AMI) trial, a multicenter double-blind trial of the intracoronary infusion of BMMNCs after successful percutaneous coronary intervention for acute MI.20 At 4 months, the absolute improvement in LVEF measures by angiography was greater in patients with BMMNC versus placebo (5.5 vs. 3.0; p = 0.01). Subgroup analysis suggested that the benefit was greatest in patients with the worst LVEF at baseline. The recent Bone Marrow Transfer to Enhance ST-Elevation Infarct Regeneration (BOOST) trial reported that the relative improvement in LVEF after infusion of BMMNCs at 6 months was significant but not significant at 18 months.21, 25 One possibility is that it may be challenging to achieve significant sustained improvements in LVEF in cohorts of patients with preserved ventricular function receiving current therapies. In addition, aspects such as total ischemic time before percutaneous coronary intervention may also play a role in who benefits. A smaller Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Acute Myocardial Infarction (ASTAMI) trial involving three noninvasive imaging methods did not find a significant improvement in LVEF at 6 months in the BMMNC group versus control.26 Janssens and colleagues22 also did not detect an improvement in global ventricular function at 4 months in the BMMNC group compared with the control group, although infarct size was reduced and regional wall motion was improved in the BMMNC group. In the Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Recovery of LV Function in Patients with Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease (TOPCARE-CHD) study in which patients with nonischemic dilative cardiomyopathy were treated with approximately 200 million BMMNCs, there was a 3-month modest improvement in LVEF of 3.7 ± 4%.27 Overall, meta-analysis of many clinical trials using BMMNCs suggests a similar level of modest improvement due to reduced infarct size and improved remodeling.28, 29 The rate of adverse clinical events was found to be significantly lower at 6 months to 1 year among patients receiving BMMNCs than among those receiving placebo, including reduced incidence of death, recurrent MI, and stent thrombosis in patients with ischemic heart disease. It is important to recognize that some recent randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trials have shown negative results.24, 30, 31 Also, it is uncertain if the improvement is sustained long term (i.e., years). Refinement of therapy might be achievable by targeting cell therapies to patients with specific pathologic conditions (i.e., longer ischemic time and/or poor LVEF).

TABLE 1.

Major randomized controlled trials of BMMNCs

| Trial or investigator group | Setting | Design | Number of cells administered in treatment group |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost | AMI | 30 patients in treated and no infusion control; LVEF assessed by MRI | 2.5 ×109 | At 6 months: LVEF 6% greater in cell group |

| At 18 months: no significant difference in LVEF | ||||

| Janssens et al.22 | AMI | Double blind with 33 patients received cell; 34 received placebo infusion; LVEF was assessed by MRI | 3 ×108 | At 4 months: no significant difference in overall LVEF; decreased infract size and better regional LV motion in cell group |

| TOPCARE-CHD | Chronic LV dysfunction | Crossover trial: 24 patients received EPCs, 28 received BMMNCs, 23 received no infusion. LVEF assessed by angiography | 2 × 108 BMMNCs or 2 ×107 peripheral blood-derived EPCs | At 3 months: greater increase in LVEF (2.9 percentage points) in BMMNC group than in EPC group or control group |

| ASTAMI | AMI | Randomized trial: 47 patients received BMMNCs; 50 received no infusion LVEF assessed by SPECT, echocardiography, and MRI | 7×107 | At 6 months: no significant difference in LVEF between the two groups |

| REPAIR-AMI | AMI | Randomized, double-blind trial: 101 patients received cells; 98 received placebo infusion LVEF assessed by LV angiography | 2.4×108 | At 4 months: greater LVEF in cell group than in placebo group (5.5% vs. 3.0%) |

| At 1 year: reduction in combined adverse clinical events in cell group vs. placebo | ||||

| CCTRN (TIME) trials | AMI with infusions 3 or 7 days (early TIME) vs. 2–3 weeks (late TIME) | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing LVEF, LV volume, and infarct size | 1.5 × 108 | Global or regional function not different from placebo in either TIME cohorts |

| CCTRN (FOCUS) | Symptomatic HF with LVEF < 45% | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing LVEF | 1.0 × 108 | LVEF using SPECT showed no difference from control |

AMI = acute myocardial infarction.

The effect of BM cell populations such as CD34+ cells, CD133+ cells, MSCs, or EPCs have been evaluated in a significantly smaller cohort of patients. The TOPCARE-CHD trial evaluated BMMNCs or EPCs in patients with ventricular dysfunction.27 In this randomized crossover trial, the absolute change in LVEF was significantly greater among patients receiving BMMNCs than among those receiving EPCs derived from outgrowth of cultured circulating cells. However, the benefit in BMMNCs infusion was modest at 2.9%. A number of clinical trials with MSCs (TAC-HFT, POSEIDON, etc.) are ongoing but the preliminary data suggest a small benefit.32 Most recently, a small feasibility and safety randomized trial studied administration of MSCs injected during left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation (Table 2). The results suggest that MSCs in this setting are safe with a potential for efficacy as reflected by more successful temporary weaning from LVAD in the cell-treated group.33 MSCs, which can be easily cultured and expanded ex vivo to large therapeutic doses, represent a promising source of cellular therapy if the initial results can be confirmed. ASCs are being used in ongoing trials (PRECISE and APOLLO) for treatment of nonrevascularizable ischemic myocardium.34 Standardization of the definition of MSC by the International Society for Cellular Therapy may aid in standardizing cell potency for current and future trials.35 However, MSC preparations are composed of subsets with different phenotype and function,36, 37 and it is not yet understood how this heterogeneity could affect therapeutic efficacy. Most recently, a multicenter, randomized Cardiopoietic Stem Cell Therapy in Heart Failure (C-CURE) trial is using a approach of MSCs that have been “preprimed” by a cardiogenic cocktail before endomyocardial injection into areas of dysfunctional myocardium (Table 2).38 Patients receiving preprimed MSCs showed improved cardiac function and remodeling and improved exercise tolerance compared to patients receiving standard care.38 These findings merit follow-up in larger trials, in particular, as other studies did not provide evidence of cardiomyogenic differentiation of MSCs.39, 40 If the results can be replicated and if preprimed MSCs actually perform better than nonpreprimed MSCs, the application of preprimed MSCs may be potentially applied to vascular or neural repair. More specialized cell populations such as hematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+ or CD133+ populations) used in both ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy provided improvement in regional perfusion and LV remodeling.12 These studies were limited by small trial size and difficulty in obtaining specialized cells.

TABLE 2.

Randomized controlled trials of MSCs and CPCs for cardiac disease*

| Trial or investigator group | Setting | Design | Number of cells administered in treatment group |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSEIDON | Transendocardial injections into 10 LV sites to patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy | Randomized trial of 30 patients; 15 patients received escalating dose of either autologous or allogeneic MSCs | Approximately 2 × 107–8 BMMSCs | At 12 months, both recipients of allogeneic and autologous MSCs were suggestive of reduced infarct size, improved remodeling measured by sphericity index |

| C-CURE | NOGA-guided endoventricular injections | Randomized, two-arm study of 32 patients receiving cardiopoietic MSCs vs. 15 patients receiving standard of care. | Approx. 6×108–12×108 cardiopoietic autologous MSCs | At 6 months: LVEF was improved by approx. 5% with favorable remodeling and improved 6% in walk-in cell therapy arm |

| SCIPIO | Intracoronary after 4 months after CABG surgery | Randomized, open label. In the second phase, 24 patients received CPCs, 32 control patients with no catheterization | 5 × 105–10 × 105 cKit+ autologous CPCs | Improved LVEF at 4 months and 1 year. Decreased infarct size in CPC-treated patients |

| CADUCEUS | Intracoronary within 36 days of biopsy in patients with recent Ml and moderate LV dysfunction | Randomized trial. 17 patients received cardiospheres; 14 received standard of care | 6 × 109–12 × 109 autologous cardiospheres | At 1 year, scar mass decreased with increased viable tissue; better regional LV function and overall EF |

LV remodeling was determined by calculating LV volumes using echocardiography-derived LV dimensions.

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft.

Two recent clinical trials demonstrate that cKit+ cardiac progenitor cells can be isolated from human cardiac tissue and clonally expanded in vitro to sufficient numbers for clinical cellular therapy (Table 2).41, 42 In the CADUCEUS trial, autologous cardiospheres (which include a small population of cKit+/lin− cells but also other progenitor populations, such as CD105+ and CD90+)43 injected a few weeks after MI into the affected coronary artery resulted in “an unprecedented increase in viable myocardium” at 6 months, albeit a modest effect in EF (38.8% at baseline vs. 41.2% after treatment).42, 44 At 1 year, the improvements in scar size and viable myocardium were still noted, albeit there were no significant changes in global function.43 In the SCIPIO trial, autologous cKit+/lin− cells isolated from right atrial appendage were expanded ex vivo and injected by intracoronary infusion a few months after coronary artery bypass grafting.41 The results showed significant LV functional improvement and reduction in infarct size at 4 months in patients. The improvements became more pronounced at 8 months and 1 year with a striking 13.6% increase in ejection fraction at 1 year concomitant with an increase in mass of viable LV. These results are both exciting and promising and need to be repeated in larger clinical trials. The observed increase in viable myocardium is suggestive of muscle regeneration, but does not prove that actual regeneration from progenitor cells is occurring.41

MECHANISTIC BASIS OF OBSERVED CLINICAL EFFICACY

The mechanisms by which cellular therapies improve organ function remain under intense study. With regard to BM-derived cellular therapies, animal studies support the importance of the release of trophic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory factors (i.e., particularly MSCs) as important mechanisms driving the observed improved LV variables and clinical outcomes.45 These studies suggest that the release of paracrine factors modulate cardiac cell apoptosis, neovascularization, fibrosis, and even stimulation of endogenous cardiac stem cell recruitment and differentiation.45 A number of studies provide evidence of therapeutic efficacy in MI by factors that are secreted by MSCs: activin A, epiregulin, endothelin, glypican-3, IGFBP-7, LRP-6, osteoprotegerin, sFRP-4, Smad4/7, thrombospondin-1, TIMP-1/2, VEGF, various growth factors (review, Williams and Hare46), IGF-1 (review, Schafer and Northoff47), and also MSC-conditioned medium improves cardiac function after MI.48, 49 Yet, many details of which paracrine factors or how these effects are orchestrated are unknown. Other mechanisms, such as engraftment and differentiation into muscle of neovasculature, have been shown in animals, albeit at very low levels, but not demonstrated in humans. It is clear that we need to continue to enhance our understanding of both cellular and molecular mechanisms underpinning organ repair with stem cell therapy. The enrollment of HF patients with LVADs (used to provide bridge to transplantation) may provide an opportunity to analyze cardiac tissue at the time of transplantation and thereafter to address some of these unanswered questions.

Overall, the benefits of most BM cell–derived therapies remain modest. While multiple variables (cell type, dose, timing, degree of organ dysfunction, etc.) play a role, it is well recognized that implanted cells survive briefly after implantation. In animal studies, only 20% of the cells remain in 24 hours.50, 51 In the BOOST trial using BMMNCs, only 3% of the implanted cells remained at 30 days.51 Together, the data suggest a lack of even short-term survival of implanted cells in the ischemic milieu. Regardless of whether the mechanisms of repair reflects their differentiation (direct contribution) or paracrine effects, the stem cells must be able to successfully reach the wound, survive, and possibly expand within it to enhance repair.51 Hence, low survival and poor engraftment of stem cells greatly limit their therapeutic efficacy.

THE REGULATORY CHALLENGES IN MANUFACTURING CELL THERAPY PRODUCT FOR CARDIAC APPLICATIONS

As outlined, a steadily increasing variety of cell types for cell therapy of cardiac diseases is available. However, there are considerable bumps on the road from a cell type candidate to a clinical cell product. As discussed, the great variety of options (cell source, timing, dose, route of administration) and still surprisingly poor mechanistic insights pose major challenges to this undertaking.52 The production of cell products poses complex challenges, particularly with product characterizations. These challenges include the variability and complexity of the cells, need for sterile processing, limitation on amount of product, difficulty in assessing potency, and challenges to product storage and distribution.

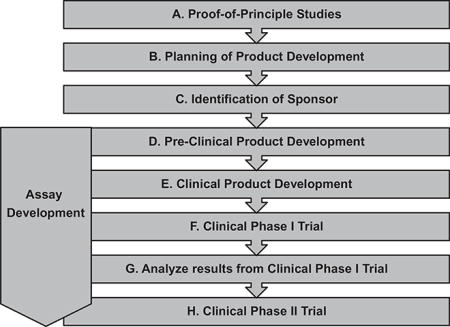

Regulatory institutions such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency are not only approving authorities but also serve as resourceful and supportive partners in cell therapy development. These oversight and regulatory agencies ensure that applications of cell therapies are manufactured according to current Good Tissue Practice requirements, which address the methods, facilities, and controls used for manufacturing cell therapy products to prevent the introduction, transfusion, and spread of communicable diseases.53 In cases where the cell therapy products require more complex manipulations, current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) and quality systems regulations, which are already in place for products such as drugs, biologics, and devices, also apply.54 It is valuable to closely interact with the appropriate agency at each phase of the product development process. A generalized overview and roadmap to a cell therapy product that does not yet have market approval is delineated in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

A possible roadmap to a cell therapy product for cardiac applications

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Objective | Features | Design/ establish SOPs |

Specific features/challenges/ possible solutions |

Consult regulatory authorities (FDA, EMA) |

Consult supportive resources (PACT, AABB) |

| A. Proof-of-principle studies | To identify novel cell therapy candidate and to provide scientific rationale for future clinical application. | (Basic) characterization of cell type candidate. In vivo proof of efficacy (animal model). | ||||

| Insights of mechanisms of action. | ||||||

| B. Planning of product development | To elaborate a detailed plan of the whole process. | Defining goals, needs, and timelines. Reassemble the team. | Academic institutions with little experience in product development: consider consulting experienced industry. | X | X | |

| C. Identification of sponsor | To allocate sustainable financial support for the entire process (preclinical and clinical). | Detailed financial outline for product development process including projected and preliminary business plan. | To stratify risks: consider sustainable sponsoring from different sources (e.g., Sponsor A until IND filing. Sponsor B for clinical studies). Consider/plan commercialization and patent filing. | |||

| D. Preclinical product development | ||||||

| D.1. Optimization of cell culture and storage according to cGMP | To develop isolation, in vitro expansion. and cryopreservation protocols of elected cell type. | Identify cGMP grade supply material for manufacturing (media, supplements, consumables). | X | Ensure sustainable supply of manufacturing material (e.g., specific lots) as development process could extend to several years. | ||

| D.2. Up-scaling of cell manufacturing | To conduct scale-up studies. | Adjust protocols for up-scaled production under cGMP | X | |||

| D.3. Assay development | To develop assays to assess identity purity efficacy and safety of cell product. | Design and validate in vitro assays (flow cytometry, qPCR, functional assays, cytogenetics). | X | Start with basic assays (viability, purity, safety). Develop efficacy assays in parallel with clinical studies (based on clinical data correlated to product specifications). | ||

| E. Clinical product development | ||||||

| E.1. Elect cGMP manufacturing site/service | To manufacture and store cell banks and clinical lots according to cGMP | State-of-the art cGMP facility featuring clean rooms(s), experienced staff, and quality management system. | Identify and audit certified GMP facility that accommodate the specific needs of the manufacturing process. | |||

| E.2. Technology transfer | To transfer technology from the development site to the cGMP production site. | Transfer SOPs and know-how. | X | Ensure complete implementation of preclinical product development process to cGMP manufacturing site as this is key for successful production of cell product. Consider frequent face-to-face meetings and audits. Establish convenient and efficient communication platform accessible for development and manufacturing teams and clinical application sites. | ||

| E.3. Master cell bank | To generate a master cell bank. | Generate sufficient cell material that serves as resource and backup for all downstream manufacturing processes. Determine optimal cell number per vial for cryopreservation. | X | Estimate cell supply (+20% extra back-up) to accommodate mid- to long-term clinical need. Consult clinicians who consider future application of cell product. Consider different clinical applications for one cell product | ||

| E.4. Working cell bank(s) | To generate (a) working cell bank(s). | Generate sufficient cell material that serves as resource for downstream manufacturing processes. | X | |||

| File pre-IND | X | |||||

| E.5. Determine application procedure | To determine definitive route of administration for clinical study | Identify and work with clinical partners who will apply cell product according to cGCP. | X | Technical adjustments of application procedure/device (e.g., catheter) might be needed to apply cell product in sufficient numbers and optimal condition. | ||

| E.6. Dose finding | To determine cell dose for clinical Phase I study | Conduct in vivo animal studies to assess dose depending efficacy. | X | |||

| E.7. Safety and toxicity studies | To assess in vivo safety and toxicity | Conduct in vivo animal studies in a Good Laboratory Practice-certified institution to assess safety and toxicity. | X | X | ||

| E.8. Transfer of cell product to the clinical application site | To determine and establish transportation procedure of cells to the clinical application sites. | Design and establish SOPs for transportation (including monitoring) from banking site(s) of clinical lot(s) to application sites. | X | Ensure complete implementation of clinical product development process to clinical application sites as this is key for successful translation of the | ||

| E.9. Training plans for clinical application sites |

To develop training plans for the clinical application sites. |

Design and establish SOPs for training plans for the clinical application sites. | X |

cell product to the clinic. Consider frequent face-to-face meetings and audits. Establish convenient and efficient communication platform accessible for development team and clinical application sites. | ||

| File IND | X | |||||

| F. Clinical Phase I trial | To assess safety of the cell product in patients. | Identify clinical endpoints. Identify most appropriate study sites (patient groups, physician specialization, resources for trial management). | X | X | ||

| G. Analyze results from clinical Phase I trial | If encouraging consider clinical Phase II trial | |||||

| H. Clinical Phase II trial | To assess efficacy of the cell product in patients. | Consider multicenter study (one cell bank/source serves patients in different clinical application sites). | X | X | ||

| Identify most appropriate study sites (patient groups, physician specialization, resources for trial management). | ||||||

cGMP = current Good Manufacturing Practice; EMA = European Medicines Agency; qPCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SOPs = standard operation procedures.

Many of the cardiac cell therapy trials have utilized unfractionated BMMNCs, which are often minimally manipulated and feature relatively simple release criteria including cell viability, nucleated cell count, and sterility.54 If the cell-based product used is a minimally manipulated product for homologous use and not combined with a FDA-regulated article, it falls under the regulation of Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act and does not require premarket approval (i.e., an investigational new drug [IND] application).54 A homologous application requires that cells (after minimal manipulation such as thawing and dilution) are administered into the tissue of origin (BM cells are injected into BM space). However, if BM cells are injected into the joint space or heart, for example, an IND is necessary. Thus all cardiac cellular therapies utilized thus far, including cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) due to their extensive processing, would require an IND.

DETERMINATION OF REGENERATIVE POTENCY OF CELL THERAPY PRODUCT REMAINS A CHALLENGE

Product characterization and analysis of product potency of cell products are complex and not well established. Potency measurements should theoretically correlate with the intended biologic activity or function in preclinical animal models and clinical outcomes. It is unclear how meaningful in vitro performance of MSCs (e.g., trilineage differentiation, proliferation, suppression of T-cell proliferation) correlates with their in vivo efficacy after transplantation into the heart. In many cases, since a single assay does not adequately measure potency of the cell, the development of an assay matrix may be useful.53 Identifying true potency assays are additionally hampered by the difficulty to correlate in vitro characteristics with in vivo efficacy in real time. There is much interest and ongoing effort within the cell processing community to identify meaningful standardization guidelines and potency and/or release assays. Assessing potency is of particular importance when cells are manipulated and expanded in culture. To determine the scalability of various cell sources such as CPCs, MSCs, or ASCs, it will be critical to elucidate the molecular pathways required to maintain the self-renewal, survival, and genomic stability.

Although the use of autologous therapies does not use a cell banking system, the establishment of cell banks is a viable consideration for allogeneic MSC or ASCs. The benefit of autologous cell source is that it requires no HLA matching, no worries of immune rejection or alloreactivity (i.e., generation of HLA antibodies in recipient), or immunosuppression. The question of whether autologous and allogeneic MSCs will exert similar therapeutic efficacy was explored in the POSEIDON trial (see Table 2).32 Although small, this trial suggests that allogeneic MSCs are similar in efficacy to autologous with no significant immune effects in the host, setting the stage for future allogeneic MSC-based regenerative trials.32 Both MSC and ASCs can be expanded in vitro and cryopreserved over prolonged time, aspects that are prerequisites to generate a master cell bank. Although a working master cell bank allows for more practical management of donor(s) and in-process and release testing of cell therapy products, the drawbacks are that these cells may be of higher passage number. Without reliable potency assays, it is difficult to assess the therapeutic potential of the banked cells.

CONSIDERATION OF SCALABILITY OF CELL SOURCES

A major bottleneck in some types of cell therapy productions (i.e., cardiopoietic MSCs and CPCs) is scalability.38, 55 These involve complex differentiation media that are expensive and that make it difficult to manufacture by GMP production from protocols developed in the research lab.38, 55 In the SCIPIO trials, the time required to expand sufficient cKit+ CPCs from small biopsy material was months. The isolation, maintenance requirement, and expansion capacity of cardiac progenitors are all challenging and successful large-scale production have only been performed in a few sites using conventional two-dimensional tissue culture.56 Currently, there are relatively few publications describing successful scalability platforms for these cell therapy sources.57

NIH-SUPPORTED CARDIAC CELL THERAPY

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) recognized the numerous challenges (i.e., cost, technical expertise, regulatory) of translating cellular therapies from preclinical to the clinical phase. To foster the growth of novel cardiovascular cellular therapies the Production Assistance for Cellular Therapies (PACT) program, which consists of five cell-processing facilities scattered across the United States, was initiated as a scientific, regulatory, and educational resource to the cell therapy community. PACT provides product development and manufacturing support to investigators for clinical-grade cellular therapies. PACT centers at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Minnesota have provided cell-processing services to the NHLBI Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (CCTRN)-sponsored trials involving BMMNCs after acute MI (TIME and lateTIME) and in HF (FOCUS).

The CCTNR-supported trials represented the first multicenter evaluation of BMMNC-based therapy in the United States. Harvested BM was processed on site via a closed, automated cell processing system (Sepax, Biosafe Group SA, Eysins, Switzerland) and the isolated cells were suspended in and delivered in 5% human serum albumin. A rationale for using the Sepax system was that it enabled GMP-grade processing as well as standardization of methodology across multiple centers. Cells were injected within 12 hours of harvesting. The average number of cells in CCTRN-sponsored trials was 1 × 108 to 1.5 × 108 nucleated cells. Transplanted cell doses of BMMNCs for cardiac applications ranged from 1 × 105 cells/kg up to 2.4 × 109 cells, underwent different enriching techniques (i.e., manual processing via Ficoll gradient vs. automated enrichment for MNCs via Sepax) and also distinct vehicles for infusion, highlighting at least some source of variability in clinical outcome.58

One of the challenges with cardiac cell BMMNC-based cell therapy is delivering fresh products within a small window of time. At our institution (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN), a processing lab technologist (PLT) was present during the BM harvest, which occurred early in the morning in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The PLT arrived to the BM harvest with a dozen heparinized syringes and returned with approximately 90 mL of BM distributed into multiple syringes for further processing in the laboratory. The product was subsequently transferred to the Sepax kit and underwent automated processing. After automated processing, the product was then sampled to enumerate the total nucleated count, for endotoxin testing and stat Gram stain. Additional samples were set aside for bacterial and fungal culture, CD34 enumeration, and CFU tests as well as protocol-related archiving and testing. Once the stat test results were received, the PLT could log into the CCTRN Web site for randomization. For the TIME trials, the product (approx. 30 mL) was subsequently transferred into bags. However, for the FOCUS trial, the 3-mL product was transferred into sterile syringes suitable to enter the sterile field. The transfer and preparation of this syringe required two PLTs to accomplish. The product was delivered to the catheterization suite by the PLT for infusion. Typically, the process took approximately 4 to 6 hours of processing time by a PLT. Additional time was required to obtain and deliver the product as well as complete and submit the paperwork after all testing results were available. Using off-the-shelf cell therapy products should significantly facilitate the time and effort required from the cell therapy lab.

CONCLUSION

The hope and enthusiasm for a future in which cell-based therapies may serve as a therapeutic foundation for cardiac repair remain high. There are many outstanding hurdles, not only from the clinical angle, which include identifying the eligible patient, selecting timing and method of cell administration, and selecting the correct type of cell, but also from the cell processing lab in terms of establishing process standardization to produce a safe, pure, and potent cellular product. Continued research in preclinical and clinical studies is needed to ensure the realization of cardiac regeneration by cell therapy.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ASC(s)

adipose-derived stromal cell(s)

- BMMNC(s)

bone marrow–derived mononuclear cell(s)

- CCTRN

Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network

- CPC(s)

cardiac progenitor cell(s)

- EPC(s)

endothelial progenitor cell(s)

- HF

heart failure

- IND

investigational new drug

- LV

left ventricular

- LVAD(s)

left ventricular assist device(s)

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MI(s)

myocardial infarction(s)

- MSC(s)

mesenchymal stem/stromal cells

- PACT

Production Assistance for Cellular Therapies

- PLT

processing lab technologist

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topol EJ. Current status and future prospects for acute myocardial infarction therapy. Circulation. 2003;108:III6–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086950.37612.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:17B–20B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenfeld M, Frishman WH, Leri A, et al. The existence of myocardial repair. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21:111–20. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318289d7a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–5. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs S, Baffour R, Zhou F, et al. Transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow enhances collateral perfusion and regional function in pigs with chronic experimental myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1725–32. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Silva R, Raval AN, Hadi M, et al. Intracoronary infusion of autologous mononuclear cells from bone marrow or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized apheresis product may not improve remodelling, contractile function, perfusion, or infarct size in a swine model of large myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1772–82. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moelker AD, Baks T, van den Bos EJ, et al. Reduction in infarct size, but no functional improvement after bone marrow cell administration in a porcine model of reperfused myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:3057–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuleri KH, Feigenbaum GS, Centola M, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells produce reverse remodelling in chronic ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2722–32. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston PV, Sasano T, Mills K, et al. Engraftment, differentiation, and functional benefits of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells in porcine ischemic cardiomy-opathy. Circulation. 2009;120:1075–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, White AJ, Matsushita S, et al. Intramyocardial injection of autologous cardiospheres or cardiosphere-derived cells preserves function and minimizes adverse ventricular remodeling in pigs with heart failure post-myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:455–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113:810–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, et al. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1913–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034046.87607.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perin EC, Dohmann HF, Borojevic R, et al. Transendocardial, autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for severe, chronic ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:2294–302. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070596.30552.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Ramshorst J, Bax JJ, Beeres SA, et al. Intramyocardial bone marrow cell injection for chronic myocardial ischemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1997–2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menasché P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117:1189–200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veltman CE, Soliman OII, Geleijnse ML, et al. Four-year follow-up of treatment with intramyocardial skeletal myoblasts injection in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopa-thy. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1386–96. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duckers HE, Houtgraaf J, Hehrlein C, et al. Final results of a phase IIa, randomised, open-label trial to evaluate the percutaneous intramyocardial transplantation of autologous skeletal myoblasts in congestive heart failure patients: the SEISMIC trial. EuroIntervention. 2011;6:805–12. doi: 10.4244/EIJV6I7A139. —DOI10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Povsic TJ, O’Connor CM, Henry T, et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled, multicenter study to assess the safety and cardiovascular effects of skeletal myoblast implantation by catheter delivery in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011;162:654–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schächinger V, Erbs S, Elsässer A, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssens S, Dubois C, Boggaert J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double blind, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;364:141–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roncalli J, Mouquet F, Piot C, et al. Intracoronary autologous mononucleated bone marrow cell infusion for acute myocardial infarction: results of the randomized multi-center BONAMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1748–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perin EC, Willerson JT, Pepine CJ, et al. Effect of transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow mnocuclear cells on functional capacity, left ventricular function and perfusion in chronic heart failure: the FOCUS-CCTRN trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1717–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months’ follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1287–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleland JG, Freemantle N, Coletta AP, et al. Clinical trials update from the American Heart Association: REPAIR-AMI, ASTAMI, JELIS, MEGA, REVIVE-II, SURVIVE, and PROACTIVE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assmus B, Fischer-Rasokat U, Honold J, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of functionally competent BMCs is associated with a decrease in natriuretic peptide serum levels and improved survival of patients with chronic postinfarction heart failure: results of the TOPCARE-CHD Registry. Circ Res. 2007;100:1234–41. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264508.47717.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Sun A, Zhang S, et al. Efficacy and safety of intracoronary autologous bone marrow-derived cell transplantation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: insights from randomized controlled trials with 12 or more months follow-up. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:353–60. doi: 10.1002/clc.20745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian T, Chen B, Xiao Y, et al. Intramyocardial autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traverse JH, Henry TD, Ellis SG, et al. Effect of intracoronary delivery of autologous bone marrow mono-nuclear cells 2 to 3 weeks following acute myocardial infarction on left ventricular function: the Late TIME randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:2110–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traverse JH, Henry TD, Pepine CJ, et al. Effect of the use and timing of bone marrow mononuclear cell delivery on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction: the TIME randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2380–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.28726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2369–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ascheim DD, Gelijns AC, Goldstein D, et al. Mesenchymal precursor cells as adjunctive therapy in recipients of contemporary left ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 2014;129:2287–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houtgraaf JH, den Dekker WK, van Dalen BM, et al. First experience in humans using adipose tissue-derived regenerative cells in the treatment of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:539–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchyamal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel G, Kluba T, Hermanutz-Klein U, et al. Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med. 2013;11:146–9. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churchman SM, Ponchel F, Boxall SA, et al. Transcriptional profile of native CD271+ multipotential stromal cells: evidence for multiple fates, with prominent osteogenic and Wnt pathway signaling activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2632–43. doi: 10.1002/art.34434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartunek J, Behfar A, Dolatabadi D, et al. Cardiopoietic stem cell therapy in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegel G, Krause P, Wohrle S, et al. Bone marrow derived human mesenchymal stem cells express cardiomyogenic proteins but do not exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation potential. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2457–70. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rose RA, Jiang H, Wang X, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells express cardiac-specific markers, retain the stromal phenotype, and do not become functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2884–92. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chugh AR, Beache GM, Loughran JH, et al. Administration of cardiac stem cells in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the SCIPIO trial: surgical aspects and interim analysis of myocardial function and viability by magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2012;126:S54–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malliaras K, Makkar RR, Smith RR, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells after myocardial infarction: evidence of therapeutic regeneration in the final 1 year results of CADUCEUS trial (CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricUlar dySfunction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:110–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marbán E, Malliaras K, Smith RR, et al. Cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration—Authors’ reply. Lancet. 2012;379:2426–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Schneider MD. Unchain my heart: the scientific foundations of cardiac repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:572–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI24283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology pathophysiology translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schäfer R, Northoff H. Cardioprotection and cardiac regeneration by mesenchymal stem cells. Panminerva Med. 2008;50:31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmers L, Lim SK, Arslan F, et al. Reduction of myocardial infarct size by human mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium. Stem Cell Res. 2007;1:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmers L, Lim SK, Hoefer IE, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar AH, Caplice NM. Clinical potential of adult vascular progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1080–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alfaro MP, Young PP. Lessons from genetically altered mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs); candidates for improved MSC-directed myocardial repair. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:1065–74. doi: 10.3727/096368911X612477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phinney DG, Sensebe L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: misconceptions and evolving concents. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:140e. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee MH, Arcidiacono JA, Bilek AM, et al. Considerations for tissue-engineered and regenerative medicine product development prior to clinical trials in the United States. Tissue Eng. 2010;16:41–54. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lysaght T, Campbell AV. Regulating autologous adult stem cells: the FDA steps up. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:393–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, et al. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Chen AF, Ting S, Seow J, et al. Considerations in designing systems for large scale productin of human cardiomyocytes from pluriptent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:12–25. doi: 10.1186/scrt401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lecina M, Ting S, Choo A, et al. Scalable platform for human embryonic stem cell differentiation to cardiomyocytes in suspended microcarrier cultures. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:1609–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2010.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Behfar A, Crespo-Diaz R, Terzic A, et al. Cell therapy for cardiac repair—lessons from clinical trials. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:232–46. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]