Abstract

Background

Lactic acid is being routinely used as a marker of hypoxia in aircrash investigation. Since lactic acid estimation as a marker of hypoxia in postmortem samples for aircrash investigation is prone to many interfering factors, like the postmortem production and hemolysis. A study was carried out to evaluate other hypoxia markers other than lactic acid which could be later added as markers of hypoxia in postmortem investigations of aircraft accidents.

Methods

25 healthy males of age 20–40 yrs volunteered participants were subjected to an simulated altitude of 15,000 ft for 30 min and the mean plasma concentration of Hypoxia Inducing Factor 1α (HIF 1α), Erythropoietin (EPO), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and lactic acid (LA) were analyzed from their venous blood sample collected at 4 intervals viz. Ground level pre exposure, 15,000 ft at 15 min, 15,000 ft at 30 min and Ground level 3 h post exposure.

Results

Statistical analysis revealed significant increase in mean plasma concentration of lactic acid, HIF-1α and EPO on exposure for duration of 15 min and 30 min at an altitude of 15,000 ft.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that HIF-1α and EPO are sensitive to hypoxia exposure as compared to lactic acid and can be used in association with LA as hypoxia markers. However stability of these proteins in postmortem conditions needs to be studied and the potential for estimation of mRNA transcripts of HIF-1α and EPO, which would be stable in postmortem conditions, can be explored.

Keywords: Aircrash investigation, Hypoxia markers, ELISA and Hypobaric chamber

Introduction

Acute hypobaric hypoxia had been recognized as one of the foremost physiological threats since humans ventured into the sky in balloons.1 Accidents due to hypoxia are rare, but hypoxia incidents are common. When fatal accidents occur, hypoxia may not be recognized as a primary cause among the multitude of other potential causes. Retrospective studies conducted after the Second World War give an account of a significant number of unexplained military aircraft accidents that had been suspected to be because of hypoxia.2, 3, 4 Detection of possible hypoxia exposures during postmortem investigation of aircraft accidents has implications while determining flight safety. A study conducted by Tripathi et al from 1986 to 1995 in Army Aviation helicopter flying high altitude sorties revealed 29 accidents and hypoxia was a contributing factor in 24% of all accidents.5 Pilot incapacitation attributable to hypoxia has been confirmed as the cause of crash of IAF MiG 29 at Sirsi, Karnataka dated 11 Apr 2002.6

Lack of a suitable histopathological criterion prompted several studies to direct their attention towards the search of a biochemical marker and subsequent establishment of lactic acid as an indicator of antemortem hypoxia. Elevated lactic acid is used as a marker of antemortem hypoxia during analysis of post-mortem samples during Aircraft Accident Investigations at this Institute. However, being an end product of anaerobic glycolytic pathway, there is always the interference by lactic acid produced during postmortem in the specimens and this may confound the interpretation. Moreover, postmortem hemolysis and presence of certain drugs including barbiturates, amphetamines, opioids, cocaine metabolites, etc. in the blood sample also result in false positive increase in lactic acid levels. Thus, the need for a reliable indicator for the postmortem diagnosis of hypoxia has assumed importance. There have been very few reported studies on markers such as Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1-alpha), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Erythropoietin (EPO); furthermore, these studies have been conducted at a maximum exposure of 4000 m (13,120 ft) only. This study is unique as the markers have been studied after exposure to hypoxia at 4572 m (15,000 ft).

In this study, we decided to expose a group of healthy individuals to simulated acute hypobaric hypoxia and study the time course of changes in the plasma concentration of these acute hypoxia markers to check their significance for utilizing them as markers of hypoxia in postmortem samples.

Materials and methods

Subjects were volunteers from medical officers attending courses at our institute. Informed consent of the participants was obtained before conducting the study. The participants were selected as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned below.

-

(a)Inclusion criteria

-

i.Healthy individuals

-

ii.Gender: Male

-

iii.Age 20–40 years

-

i.

-

(b)Exclusion criteria:

-

i.Cases of anemia

-

ii.Any history of acute or chronic respiratory illness

-

iii.Smokers

-

iv.Intake of alcohol within the last 72 h

-

v.Strenuous exercise within the last 72 h

-

vi.Intake of tea/coffee within the last 72 h

-

i.

The Explosive Decompression Chamber (EDC) or Hypobaric chamber in the Dept of High Altitude Physiology & Hyperbaric Medicine was utilized to induce hypoxia. This chamber is custom-made for the institute by KASCO Industries, Pune. The Hypobaric chamber has the following two parts – Main and Air Lock Chamber (MC and ALC, respectively). The MC houses 10 seats and the ALC four seats. The MC can go up to 15,240 m (50,000 ft) and the ALC up to 30,480 m (100,000 ft). The maximum ascent and descent rate is 80 m/s. The chamber has provision for both manual and automated control via a central control unit (work space).

Ear clearance run as per the existing policy was done on subjects before the study. Ear clearance run is given from ground level at Bangalore 914 m (3000 ft) to 3048 m (10,000 ft) at the ascent and descent rate of 914 m per minute. This profile creates a differential pressure of 157 mm of Hg across the middle ear that is well within the TM rupture pressure. This aids the trainees in equalizing the middle ear pressure voluntarily as taught during the briefing sessions. This check also ensures that individuals in the chamber are able to return to ground level in further runs without any difficulty in pressure equalization.

In our study, the participants were taken in the Hypobaric or EDC without supplemental oxygen to 4572 m (15,000 ft) altitude at an ascent rate of 914 m (3000 ft)/min and were observed in the chamber for 30 min. The profile for ear clearance run and hypoxia exposure is as shown in picture (Fig. 1). The subjects were continuously monitored at the control station through camera and by one to one communication system as well as general PA system. The medical attendants inside the chamber were on 100% oxygen throughout the study.

Fig. 1.

Profile for ear clearance run and hypoxia exposure in this study.

An altitude of 4572 m was chosen because of the comfort of the subjects, as exposure beyond 4572 m and up to 6096 m (20,000 ft) is known to produce a Stage of Disturbance,7 where the physiologic compensatory mechanisms are unable to maintain homeostasis. The ethical issues involved and the risk of DCS (Decompression sickness) are some of the other factors instrumental for the selection of 4572 m as the altitude of choice. The duration of 30 min was selected because the Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC) at 15,000 ft is 30 min or more8 and adequate time was needed for collection of venous blood sample.

The first venous blood samples from subjects were collected before the chamber run and IV catheter was placed in site for subsequent samples. The second and third samples were collected at 15 and 30 min of exposure, respectively, and the fourth sample collection was done 3 h after the subjects were brought back to ground level. The plasma was separated from the blood samples of all the 4 time points and stored at −20 °C for further analysis. The fourth sample was collected 3 h after termination of hypoxic exposure, as studies have shown the concentration of certain biomarkers to increase even after 1.5 h of termination of hypoxic exposure.9

Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1-alpha), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), and Erythropoietin (EPO) were estimated in duplicate plasma samples by commercially available ELISA kits as per the manufacturer's instructions (sandwich format Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, kits of HIF-1-alpha and EPO from Cloud-Clone Corp.®, and VEGF from Koma Biotech Inc.®). Lactic acid was estimated immediately after separation of plasma (before storage at −20 °C) by using biochemical kits from Trinity Biotech®. The changes in the levels of hypoxia markers in the 4 time points in comparison with lactic acid were determined.

A Repeated measures ANOVA was employed. The two factors were Hypoxia markers (viz. HIF 1α, EPO, VEGF and LA) and Exposure levels (viz. Ground level pre exposure, 15 min at 4572 m, 30 min at 4572 m, and Ground level post exposure). Level of significance was set at p < 0.05 and Bonferroni post hoc analysis was done.

Results

A total of 25 healthy males were subjected to simulated hypoxic stress in the Decompression Chamber and venous blood samples were collected at 4 intervals and comparisons were done between baseline pre exposure values and various exposure conditions (viz. 4572 m for 15 min, 4572 m for 30 min and ground level 3 h post exposure) to determine any significant change in the concentration of various biochemical markers.

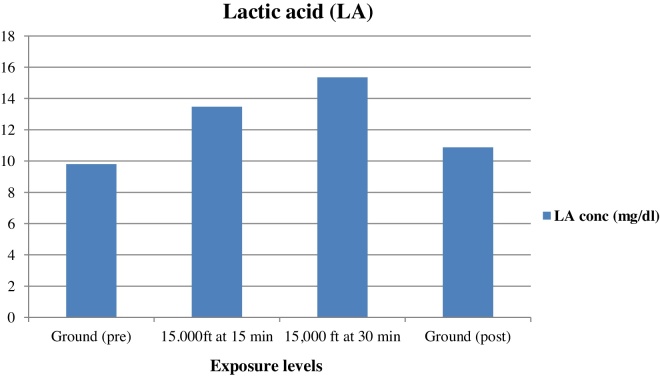

The mean concentration of plasma HIF-1α, EPO, and lactic acid increased on exposure to an altitude of 4572 m for a duration of 15 min, further rise in concentration was observed on exposure for duration of 30 min at the same altitude and the concentration decreased on returning back to ground level. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation plasma HIF-1α, EPO, VEGF, and lactic acid at various exposure levels and the mean concentrations of plasma HIF-1α, EPO, VEGF and lactic acid at different exposure levels for all (n = 25) are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of plasma HIF-1α, EPO, VEGF and lactic acid at various exposure levels and significance of these markers at various exposure levels in comparison to baseline plasma concentration pre exposure.

| Exposure level | HIF1α Mean ± SD (ng/ml) |

EPO Mean ± SD (pg/ml) |

VEGF Mean ± SD (ng/ml) |

Lactic acid Mean ± SD (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground (pre) | 0.09 ± 0.050 | 36.65 ± 13.07 | 49.84 ± 15.12 | 9.80 ± 1.56 |

| 15 min at 4572 m | 0.20 ± 0.114 p = 0.001 |

50.94 ± 21.58 p = 0.003 |

52.62 ± 14.61 p = 1.000 |

13.47 ± 1.85 p = 0.001 |

| 30 min at 4572 m | 0.33 ± 0.198 p = 0.001 |

62.39 ± 39.89 p = 0.011 |

52.29 ± 14.90 p = 1.000 |

15.36 ± 2.05 p = 0.001 |

| Ground (post 3 h) | 0.12 ± 0.072 p = 0.019 |

41.50 ± 14.70 p = 0.094 |

51.11 ± 15.44 p = 0.525 |

10.88 ± 1.87 p = 0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Mean concentrations of plasma HIF-1α at different exposure levels for all subjects (n = 25).

Fig. 3.

Mean concentrations of plasma EPO at different exposure levels for all subjects (n = 25).

Fig. 4.

Mean concentrations of plasma VEGF at different exposure levels for all subjects (n = 25).

Fig. 5.

Mean concentrations of plasma lactic acid at different exposure levels for all subjects (n = 25).

When these results were compared with the mean baseline pre exposure ground levels, it is seen that all the three values (at 4572 m for 15 min, 4572 m for 30 min and ground level 3 h post exposure) in respect of HIF-1α and lactic acid were highly significant (Table 1).

A comparison of the percentage increase in mean plasma concentration of the 3 markers (viz. LA, HIF-1α and EPO) revealed that the rise in plasma concentration of LA was 37% and 57% for the duration of hypoxia exposure of 15 min and 30 min respectively from baseline values. However, EPO showed a rise in mean plasma concentration of 39% and 70% respectively for the same exposure levels from baseline values. The maximum increase occurred in the mean plasma concentration of HIF-1α, which increased by 122% and 267% respectively from baseline values for the same exposure levels.

Discussion

A total of 25 healthy males participated in this study for exposure to hypoxia by simulation in the Decompression chamber. Most reported studies on these hypoxic markers have gone only up to 4000 m.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 This study is unique as the markers have been studied after exposure to hypoxia at 4572 m.

This study shows that statistically significant increase in mean plasma concentration of lactic acid, HIF-1α, and EPO occurred after 15 min at 4572 m and after 30 min at the same altitude (Table 1 and Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 5). The plasma concentration of these markers decreased after 3 h of termination of the hypoxic exposure, the decrease being statistically significant in the case of lactic acid and HIF-1α. No significant changes were observed in the mean plasma concentrations of plasma VEGF.

The chamber based hypoxia is most realistic for simulation of hypoxia on ground because reduction in the partial pressure of oxygen consequent due to reduction in the atmospheric pressure resulting in hypoxia is the physiological basis in both situations. The author used validated kits for all biomarkers to study the changes in the plasma concentration upon exposure to simulated hypoxia in the chamber, which is the most realistic way to simulate the hypoxia.

The rise in mean plasma HIF-1α concentration on hypoxia exposure of 4572 m for duration of 15 min and 30 min, as observed in this study could be explained on the basis of escape of its proteasome dependent degradation as reported by Berra et al.14 Another study conducted on high level endurance athletes after 3 h exposure at a simulated altitude of 3000 m (9840 ft) had shown increase in the amount of HIF-1-α alpha mRNA (Table 1 and Fig. 2).13

The EPO data of this study demonstrated that the hypoxic stimulus was sufficient to trigger a hypoxia-induced response (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The increased levels of plasma EPO on exposure to hypoxic conditions was in accordance to studies conducted by various authors. Though majority of these studies had been conducted at altitudes of 2500 m (8200 ft),9, 10, 11 3000 m (9840 ft),13 or 4000 m (13,120 ft)12, 9 and durations varying from 3 h to 18 h, Ge et al.15 had reported that the altitude induced increase in EPO is “dose” dependent, with the threshold for stimulating sustained EPO release in most subjects being ≥2100–2500 m. Moreover, Eckardt et al.9 had demonstrated that elevation in EPO occurs after 84 min at 4000 m (13,120 ft) and continues to increase if hypoxia was maintained.

The marginal increase/change in VEGF (Table 1 and Fig. 4) in our study was not significant as compared to baseline levels. Most studies show a decrease in VEGF levels under hypoxia. Liu et al had reported that hypoxia regulates VEGF gene expression in endothelial cells16 whereas Oltmanns and his group induced hypoxia in 14 healthy men for 30 min by decreasing oxygen saturation to 75% and observed significant decrease in plasma VEGF concentration as compared with the normoxic control.17 In another study conducted on high level endurance athletes, Mounier et al.13 had reported that 3 h of hypoxic exposure at 3000 m (9840 ft) significantly decreased plasma VEGF concentration by 38%. We have conducted our study at an altitude of 4572 m, which is much higher than the altitude in aforementioned studies; this may explain the marginal increase/change in VEGF.

There was a significant increase in plasma lactic acid (LA) level at both exposures, at 4572 m and 3 h post exposure, at ground level (Table 1 and Fig. 5). These findings were in accordance with studies conducted by Harboe,18 who reported the threshold altitudes for increased formation of lactic acid as 4572 m and Friedeman et al.19 who reported that lactic acid begins to increase at an altitude of 4572–5486 m (18,000 ft).

It was observed that the rise in LA concentration on exposure to 4572 m for 15 min and 30 min (37.44% and 56.73% respectively) was less, as compared to the increase in concentration of plasma EPO (38.87% and 70.09% respectively) and HIF-1α (122.22% and 266.66%, respectively) at the same exposure levels, suggesting higher levels of HIF-1α and EPO over LA upon exposure to 4572 m.

This unique study was performed on fresh blood samples collected from healthy volunteers exposed to hypoxia. Following this, the plasma was separated immediately and stored at −20 °C for analysis. However, these conditions might not be similar in an actual aircraft accident scenario, where the sample collection and autopsy might be performed after a considerable period following the crash. It is also found that there is a fall in the levels of these hypoxia markers after 3 h of termination of hypoxia exposure, although they were still more than the pre-exposure levels. Further, exposure of the body to various environmental factors might initiate the process of decomposition. Therefore, whether these parameters would be stable in postmortem conditions has to be studied further, before it is used routinely in air crash autopsy samples.

Our study which has estimated these protein markers by ELISA proves that HIF-1α and EPO are good and sensitive markers of hypoxia exposure. However, as the stability of proteins in postmortem conditions is doubtful, there is a potential for estimation of mRNA transcripts of HIF-1α and EPO as mRNA, which would be stable in postmortem conditions also20, 21 and in the real scenario of aircraft accident investigations. It is therefore recommended that studies on mRNA transcripts/gene expression of HIF-1α and EPO in response to hypoxia be undertaken so that we can use them as a panel while screening aircraft accidents for the possibility of hypoxia.

Conclusion

This study suggested that HIF-1α and EPO are more sensitive to hypoxia exposure as compared to LA and can be used in association with LA as hypoxia markers.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 4243/2012 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

References

- 1.Engle E., Lott A.S. Man in Flight. Biomedical Achievements in Aerospace. Leeward Publications; Annapolis, MD: 1979. From montgolfier to stratolab; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konecci E.B. Physiologic factors in aircraft accidents in the US Air Force. J Aviat Med. 1957;28:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis R.B., Haymaker W. High altitude hypoxia. Observations at autopsy in seventy five cases and an analysis of the causes of hypoxia. J Aviat Med. 1948;19:306–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mc Burney L.J., Watson W.J., Radomski M.W. Evaluation of tissue postmortem lactates in accident investigations using an animal model. Aerospace Med. 1974;45(8):883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripathi K.K., Gupta J.K., Kapur R.R. Aircraft Accidents in Indian Army Aviation – a general review since its inception. Ind J Aerosp Med. 1996;40(1):7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardex No 611 medical report on a major aircraft accident, IAFF (MS) – 1956 dated 11 April 2002 in respect of MiG 29 of 223 Sqn AF of IAF.

- 7.Gradwell D.P. Hypoxia and hyperventilation. In: Rainford D.J., Gradwell D.P., editors. Ernsting's Aviation Medicine. 4th ed. Hodder Arnold; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff M. PIA Air Safety Publication; 2006. Cabin Decompression and Hypoxia. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckardt K., Boutellier U., Kurtz A., Schopen M., Koller E., Bauer C. Rate of erythropoietin formation in humans in response to acute hypobaric hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1785–1788. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman R.F., Stray-Gundersen J., Levine B.D. Individual variation in response to altitude training. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1448–1456. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine B.D., Stray-Gundersen J. “Living high-training low”: effect of moderate-altitude acclimatization with low-altitude training on performance. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:102–112. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavlicek V., Marti H.H., Grad S. Effects of hypobaric hypoxia on vascular endothelial growth factor and the acute phase response in subjects who are susceptible to high-altitude pulmonary oedema. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;81:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s004210050074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mounier R., Pialoux V., Schmitt L. Effects of acute hypoxia tests on blood markers in high level endurance athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(July (5)):713–720. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berra E., Roux D., Richard D.E., Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) escapes O2 driven proteasomal degradation irrespective of its subcellular location: nucleus or cytoplasm. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(7):615–620. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge R.L., Witkowski S., Zhang Y. Determinants of erythropoietin release in response to short-term hypobaric hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2002:2361–2367. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00684.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y., Cox S.R., Morita T. Hypoxia regulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor gene expression in endothelial cells. Identification of a 5′ enhancer. Circ Res. 1995 Sep;77(3):638–643. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oltmanns K.M., Gehring H., Rudolf S. Acute hypoxia decreases plasma VEGF concentration in healthy humans. Am J Physio Endocrino Metab. 2006;290:434–439. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00508.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harboe M. Acta Physiol Scand. 1957;40:248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1957.tb01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lorentzen F.V. Lactic acid in blood after various combinations of exercise and hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1962;17(4):661–664. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1962.17.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedeman T.E., Haugen G.E., Kimieciak T.C. Pyruvic acid III. The level of pyruvic and lactic acids and the lactic pyruvic ratio, in the blood of human subjects. The effect of food, light muscular activity and anoxia at high altitude. J Biol Chem. 1945;157:673–689. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao D., Zhu B.L., Ishikawa T. Real time RT-PCR quantitative assays and post mortem degradation profiles of erythropoietin, vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha mRNA transcripts in forensic autopsy materials. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2006;8(March (2)):132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao D., Zhu B.L., Ishikawa T. Quantitative RT-PCR assays of hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha, erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA transcripts in the kidneys with regard to the cause of death in medico-legal autopsy. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2006;8(October (5)):258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]