Abstract

Background

Tungiasis is an ectoparasitosis caused by the sand flea Tunga penetrans. It is endemic in the under privileged communities of Latin America, the Caribbean and Sub Saharan Africa with geographic and seasonal variations even within endemic areas. We describe investigation of an outbreak of Tungiasis in troops deployed as part of UN peacekeeping force in Central Africa.

Methods

Tungiasis was diagnosed in an unusually large number of cases of severely pruritic boils over feet in soldiers of a UN peacekeeping battalion. An outbreak investigation was carried out and the outbreak was described in time, place and person distribution. A retrospective cohort study was done to ascertain the associated risk factors.

Results

A total of 36 cases were identified of which 33 had laboratory confirmation. Of the 36 cases, 10(27.77%) had only Fortaleza Stage II lesions, 22 (61.11%) a combination of Fortaleza Stage II and III lesions and four (11.11%) cases had a combination of Stage, II, III and IV lesions. Secondary bacterial infection was seen in 25 (69.44%) cases. Epidemiological analysis revealed that it was a common source single exposure outbreak traced to a temporary campsite along one of the patrolling routes.

Conclusion

In a Military setting an integrated approach combining health education and environmental control is required to prevent such outbreaks.

Keywords: Tungiasis, Tunga, Ectoparasitic infestations, Flea infestations, Disease outbreaks

Introduction

Exposure to bites, stings, secretions of insects, can result in a wide variety of diseases ranging from benign to multi-system life threatening illnesses. While dermatitis and diseases related to insect exposure in a particular locale may be easily recognizable, clinicians in the armed forces must also be aware of the more exotic insect related diseases as soldiers often travel to remote areas of the country and the world to discharge their duties and keep themselves abreast with the knowledge of the disease endemic to the area where the troops are deployed.

One such disease is Tungiasis, an ectoparasitosis, which is endemic in Central and South America, the Caribbean and the whole sub-Saharan region of Africa. Tungiasis is caused by infestation with the female flea Tunga penetrans (TP, Siphonaptera: Tungidae, Tunginae), also known as sand flea, jigger, nigua, or chigo. The natural habitat of TP is the sandy, warm soil of deserts and beaches and close to farms. Even within endemic regions, the distribution of tungiasis is patchy, and the disease occurs predominantly in impoverished populations.1, 2

The disease is relatively unknown in the Indian sub-continent, although there have been occasional case reports from the west coast of India.3 While the knowledge about Tungiasis and its causative agent is high in the populace of endemic/hyperendemic areas,4 the same is not true for subjects from non-endemic areas who travel to endemic areas. Indian Armed Forces personnel are deployed as part of United Nations (UN) peacekeeping force in different parts of the world, stay in makeshift camps in unfamiliar locales and hence are susceptible to such diseases due to a variety of reasons like naïve immune system, lack of knowledge/awareness of the disease, its causative agent and the modes of transmission amongst the troops as well as the health care providers.

A number of cases of tungiasis, presenting as multiple severely pruritic boils over feet, were reported among Indian troops of an Infantry battalion deployed as part of UN peacekeeping mission in eastern part of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Here we present the results of epidemiological investigation of this outbreak.

Materials and methods

Diagnosis of Tungiasis was made based on classical clinical presentation and microscopic examination of discharge from skin lesions. Photomicrography and histopathological examination could not be done due to non-availability of the facilities in field settings. Case definitions used were (a) probable case: Any person of the affected battalion having one or more papular or pustular lesion in the legs or any other part of the body in the preceding three weeks with a central dark punctum and a gelatinous brownish white granular discharge on needling the lesions. (b) Confirmed case: A probable case with microscopic confirmation in the form of the presence of eggs, filamentous cords of faeces or parts of the flea in the squash preparation of the extracted material from the lesion.

Epidemiological case sheet was developed and used to collect information from all cases about personal details, date of onset, clinical features, lab results and history of movement, long range patrols and temporary camps in recent past. Active search of additional cases was done by carrying out regular physical examination of all personnel staying in the affected location. Line list of all cases was prepared and the outbreak was described in terms of clinical findings of the cases and their distribution in time, place and person. The Fortaleza classification as given in Table 1 was used to classify the skin lesions of the patients.5

Table 1.

Fortaleza classification of clinical stages of Tungiaisis.

| Stage I | Itchy reddish brown spot of 1 mm |

| Stage II | Pearly white nodule with surrounding erythema and a central dark punctum |

| Stage III | Painful round watch glass like patch with surrounding hyperkeratosis/desquamation |

| Stage IV | Crusted black lesion with or without superinfection |

| Stage V | Residual scar |

Further analytical epidemiological study was done by retrospective cohort study design to ascertain the factors associated with this outbreak. Relative risks were calculated for suspected risk factors and checked for statistical significance. Population attributable risk percent, which tells about proportion of the incidence of a disease in the population that is due to exposure, was also calculated. Cases were treated with extraction of flea parts and antibiotics and control measures in form of anti flea measures Health education of troops (lectures/handouts) regular surveillance by medical officer were initiated simultaneously to prevent further spread of the disease.

Results

Clinical profile: 36 soldiers were found to be suffering from Tungiasis, out of 865 soldiers deployed in that location. 33 of these cases were confirmed by lab investigations also. All 36 cases were males being soldiers and the mean (sd) age of patients was 32.05 (5.04) years. Age distribution of cases is shown in Table 2. In all 36 cases the bite of the flea went unnoticed and did not give rise to any noticeable immediate local reaction like itching or pain. The number of lesions present varied from a solitary lesion in the least affected to fourteen lesions in the two worst affected cases. The distribution of cases according to number of lesions is shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Age distribution of cases.

| Age group (years) | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Up to 30 | 12 (33.33%) |

| 31–40 | 22 (61.11%) |

| 41–50 | 2 (5.56%) |

Table 3.

Distribution of cases according to number of skin lesions.

| Number of lesions | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| 1–5 | 25 (69.44%) |

| 5–10 | 7 (19.44%) |

| More than 10 | 04 (11.11%) |

Site of lesions

In all 36 cases the lesions were on the feet except one case, who had a solitary lesion on his left index finger. The most common location of lesion on the feet was periungual, followed by interdigital lesions, a few had occasional lesions on the planter surface of the feet. The two worst affected cases had multiple plantar lesions and lesions on the lateral border of the feet. No bullous lesions were seen.

Fortaleza stage of lesions

Of the 36 cases, 07 (19.4%) had only Fortaleza Stage II lesions, 26 (72.22%) presented with a combination of Fortaleza Stage II and III lesions, and four (11.11%) cases had a combination of Stage II, III and IV lesions as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of cases as per stages of Fortaleza classification.

| Fortaleza stage of disease | Number of cases | Assoc secondary infection |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | Nil | – |

| Stage II | 07 | 02 (28.6%) |

| Stage II & III | 26 | 15 (57.7%) |

| Stage II, III & IV | 04 | 04 (100%) |

Secondary infections

Secondary bacterial infection was seen in 21 (59.33%) cases. Six of the 36 cases (16.67%) had associated Tinea pedis, which appeared to be unrelated to the Tungiasis.

Epidemiological findings

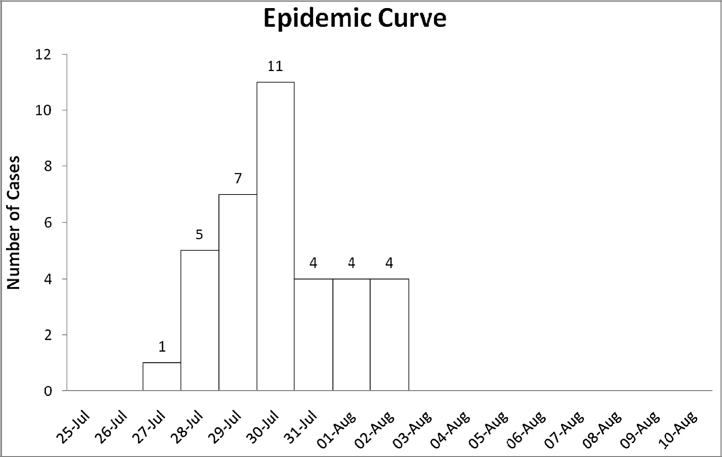

Onset of disease for all 36 cases occurred in a short time span of 07 days. Epidemic curve shown in Fig. 1 depicts rapid rise, sharp peak and abrupt fall in number of Tungiasis cases indicating a common source single exposure outbreak.

Fig. 1.

Epidemic curve of Tungiasis outbreak in DRC.

History of travel outside the camp in groups was looked into and most of the patients gave history of going on long range patrols and temporary camps in recent past. There were three long duration patrols in the recent past that involved temporary camps. Relative risk was calculated for exposure to the three patrols is shown in Table 5. This analysis showed that this outbreak was due to exposure during LRP and temp camp in Patrol 3 (Relative Risk 350.6 and Population Attributable Risk 94.18%). This patrol was carried out one week prior to the reporting of the index cases. Further interviews of the team leaders revealed that the camp site selected by this team was a dry sandy high ground surrounded by brush which is ideal environment for the Tunga flea.

Table 5.

Association of Tungiasis cases with long range patrols and temporary camps.

| Exposure – (LRP and temp camp in) | Individuals with exposure |

Individuals without exposure |

Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | Population attributable risk percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | Cases | Incidence | Total No. | Cases | Incidence | ||||

| Patrol 1 | 62 | 12 | 19.35% | 803 | 24 | 2.99% | 6.48 (3.41, 12.32) | <0.0001 | 28.19% |

| Patrol 2 | 38 | 4 | 10.53% | 827 | 32 | 3.87% | 2.72 (1.01, 7.30) | 0.04 | 7.03% |

| Patrol 3 | 40 | 34 | 85% | 825 | 2 | 0.24% | 350.63 (87.31, 1408) | <0.0001 | 94.18% |

Discussion

Tungiasis is a zoonosis that existed in Americas as early as 14th century, and is still endemic in Central and South America.6 It is believed that T. penetrans was imported to Africa at the end of the 19th centuries.7 Since then it has spread to almost all countries in sub-Saharan Africa with the point prevalence in various countries ranging from 16% to 54%.8 Within the African subcontinent while endemic Tungiasis has been reported from neighbouring countries of Uganda and Tanzania there are no reports from the eastern parts of DRC although there is anecdotal evidence that it is well known among the local population.9, 10

Troops and their accompanying medical personnel, travelling to foreign or unknown territory, should familiarize themselves with the local endemic diseases. Tungiasis is an ectoparasitosis and the flea is found in the dry sandy soil of endemic areas. Pigs are the commonest animal reservoir of Tungiasis, though dogs, cats and rats have also been implicated.11, 12 Even within endemic regions there are geographic13, 14 and seasonal variations in the prevalence with peak in dry season.15 Although the body of troops had been stationed in the locality for over eight months there were no instances of Tungiasis. The outbreak occurred following exposure to the flea at a temporary camp setup during a patrol highlighting the fact that within the same endemic zone there may be foci of high parasite index causing localized outbreaks. Such parasitic hotspots should be mapped and camping in such areas should be avoided. Intervention in the form of education of the troops on the various common zoonosis and the parasites in the area and their preventive measures were carried out. An advisory was published with the specific geographic area of the campsite as well as specific and general measures to prevent zoonotic infections and infestations. The other simple preventive measure advocated and adopted included daily spraying of campsites with insecticides, use of insect repellents, avoiding drying of clothes by spreading them on the ground.

The preferred localization for jiggers is the periungual region of feet, as the flea does not jump high therefore usually bites on exposed feet.16 The major risk factor for exposure to T. penetrans is failure to wear shoes when walking in a sandy area with active infestation. Wearing shoes and not sitting or laying in the sand, are the most important steps to reduce infection risk of not just Tungiasis but a number of other neglected tropical disorders like soil borne helminths, Buruli's ulcer, leptospirosis etc.17 During interviews of the patients it became evident that the troops resorted to using more comfortable open footwear while spending time in the camp location. Further, it was also noted that two of the four worse affected patients (more than 10 lesions) were, the chef and his assistant who spent the maximum time in the camp location. Intensity of infestation correlating with the degree of exposure has been well documented in hyper-endemic areas.18 The almost negligible incidence of Tungiasis in other UN troops stationed in the same geographical area that did not use the incriminating campsite used by this patrol.

Diagnosis of Tungiasis is based on clinical examination for the classical skin lesions and microscopic demonstration of flea parts and eggs in the lesions. On histopathology, the exoskeleton, hypodermal layer, trachea, digestive tract, and developing eggs are seen in almost all biopsy specimens but the head is rarely visualized.19 In contrast to other ectoparasitoses such as Scabies and Pediculosis, Tungiasis is a self-limiting disease with duration of four to six weeks.5 The Fortaleza classification divides the natural history of Tungiasis into five stages for clinical and epidemiological purpose. Clinically Tungiasis may be confused with furunculosis, paronychia, infected warts, Tick bite, Scabies, Fire ant sting, Myiasis, Cercarial dermatitis, and Dracunculiasis.20

The treatment of tungiasis involves the mechanical extraction of the gravid female flea under aseptic conditions. In most cases topical antibiotics are sufficient but cases with severe bacterial super infection may require systemic antibiotics. Thiabendazole and Ivermectin lotions applied on 2 consecutive days have been found effective in the treatment of Tungiasis, however oral Ivermectin was not found to be useful.21, 22 Some workers claim that occlusive application of 20% salicylated vaseline for 12 or 24 h, causes the death of the parasites and facilitates their extraction. Recently a plant based repellent Zanzarin has been found to be effective against T. penetrans.23, 24

The most common complication is secondary bacterial infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus and various enterobacteriaceae. Super-infection with anaerobic streptococci and Clostridium species have also been reported.25 In severe or long standing cases it can lead to septicaemia, lymphangitis, tetanus, and gas gangrene. Tungiasis being disease of the under privileged communities, gangrene and auto-amputation of digits has been reported in neglected cases with high parasite load.

Troops continue to be deployed for UN missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but there are very few reports of Tungiasis in the eastern regions of DRC, mainly due to lack of adequate organized medical infrastructure. Tungiasis however is an import endemic disease in the region, as seen by recent reports of high endemic load in geographically close areas to eastern DRC like Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.4, 9, 10

Conclusion

Travellers and troops visiting new locales should acquaint themselves with the diseases endemic to the region to be able to better protect themselves. Tungiasis is a disease that is endemic to many parts of the world, and even within the endemic areas, there are hyperendemic hotspots. Infestation is aided by walking barefoot and being in close contact with sources of reservoirs of infestation. In a military setting an integrated approach combining health education and environmental control is required to prevent such outbreaks.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Heukelbach J., van Haeff E., Rump B., Wilcke T., Moura R.C., Feldmeier H. Parasitic skin diseases: health care-seeking in a slum in north-east Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:368–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heukelbach J., Mencke N., Feldmeier H. Cutaneous larva migrans and tungiasis: the challenge to control zoonotic ectoparasitoses associated with poverty. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:907–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sane S.Y., Satoskar R.R. Tungiasis in Maharashtra (a case report) J Postgrad Med. 1985;31:121–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimani B., Nyagero J., Ikamari L. Knowledge, attitude and practices on jigger infestation among household members aged 18 to 60 years: case study of a rural location in Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(suppl 1):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisele M., Heukelbach J., van Marck E. Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: I. Natural history of tungiasis in man. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:87–99. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maco V., Tantalaen M., Gotuzzu E. Evidence of Tungiasis in pre-hispanic America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:855–862. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.100542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeppli R. Early references to the occurrence of Tunga penetrans in tropical Africa. Acta Trop. 1963;20:142–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heukelbach J., Ugbomoiko U.S. Tungiasis in the past and present – a dire need for intervention. Nigerian J Parasitol. 2007;28:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazigo H.D., Bahemana E., Konje E.T. Jigger flea infestation (tungiasis) in rural western Tanzania: high prevalence and severe morbidity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wafula S.T., Ssemugabo C., Namuhani N., Musoke D., Ssempebwa J., Halage A.A. Prevalence and risk factors associated with tungiasis in Mayuge district, Eastern Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:77. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.77.8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugbomoiko U.S., Ariza L., Heukelbach J. Pigs are the most important animal reservoir for Tunga penetrans (jigger flea) in rural Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2008;38:226–227. doi: 10.1258/td.2007.070352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heukelbach J., Costa A.M., Wilcke T., Mencke N., Feldmeier H. The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in severely affected communities of north-east Brazil. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Carvalho R.W., de Almeida A.B., Barbosa-Silva S.C., Amorim M., Ribeiro P.C., Serra-Freire N.M. The patterns of tungiasis in Araruama township, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:31–36. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcke T., Heukelbach J., César Sabóia Moura R., Regina Sansigolo Kerr-Pontes L., Feldmeier H. High prevalence of tungiasis in a poor neighbourhood in Fortaleza, Northeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2002;83:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heukelbach J., Wilcke T., Harms G., Feldmeier H. Seasonal variation of Tungiasis in an endemic community. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heukelbach J., Wilcke T., Eisele M., Feldmeier H. Ectopic localization of tungiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:214–216. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomczyk S., Deribe K., Brooker S.J. Association between footwear use and neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldmeier H., Kehr J.D., Poggensee G., Heukelbach J. High exposure to Tunga penetrans correlates with intensity of infestation. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:65–69. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith M.D., Procop G.W. Typical histologic features of Tunga penetrans in skin biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:714–716. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0714-THFOTP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien B.M. A practical approach to common skin problems in returning travellers. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heukelbach J., Eisele M., Jackson A. Topical treatment of tungiasis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:743–749. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heukelbach J., Franck S., Feldmeier H. Therapy of tungiasis: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial with oral Ivermectin. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:873–876. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000800015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thielecke M., Raharimanga V., Rogier C., Stauss-Grabo M., Richard V., Feldmeier H. Prevention of tungiasis and tungiasis-associated morbidity using the plant-based repellent Zanzarin: a randomized, controlled field study in rural Madagascar. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldmeier H., Kehr J.D., Heukelbach J. A plant-based repellent protects against Tunga penetrans infestation and sand flea disease. Acta Trop. 2006;99:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldmeier H., Heukelbach J., Eisele M. Bacterial superinfection in human tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:559–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]