Abstract

Background

Most studies on stress fractures in India have been carried out among recruits as against officer trainees and limited to males. With the continuous induction of women in the Armed Forces, it was decided to carry out a study among officer trainees of the three services and compare the epidemiology among genders.

Methods

A prospective study was carried out in 2011–2012 at Training Institutes of the three services where male and female cadets train together. Baseline data was collected for all trainees who joined the academy during the study period. All cadets were followed up for development of stress fractures for which details were taken. Additional information was taken from the Training Institute.

Results

A total of 3220 cadets (2612 male and 608 female cadets) were included in the study. Overall 276 cadets were observed to have stress fractures during training – making an incidence of 6.9% for male cadets and 15.8% for female cadets. Females were found to have a significantly higher incidence of stress fractures. Further the distribution and onset of stress fractures in females was observed to be distinct from males.

Conclusion

The significant gender differential observed in the study indicates differential role of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors in the causation of stress fractures among male and female. Special consideration needs to be given to these while planning and implementing measures for prevention. Further studies may be carried out on subject and on the effect of interventions in stress fracture prevention.

Keywords: Stress fractures in military training, Stress fractures in females, Prevention of stress fractures

Introduction

A stress fracture is an ‘overuse injury’ to bone that results from the accumulation of strain damage from repetitive load cycles much lower than the stress required to fracture the bone in a single-load cycle. Stress fractures are commonly associated with vigorous exercise, especially that involving repetitive, weight-bearing loads, like running or marching.1 They occur secondary to bone fatigue when normal bone is unable to keep up with repair when repeatedly damaged or stressed.2

Stress fractures are somewhat unique to military training, or at least, are seen to occur more frequently and regularly in the military compared with most athletic training programmes, except distance running.3 They are the single most important cause of hospital admissions during military training, and result in loss of training days in addition to affecting quality.

The aetiology of stress fractures is multi-factorial, and the risk factors can be broadly categorized into intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors. Intrinsic risk factors include mechanical factors such as aerobic fitness at the time of training, as well as hormonal and nutritional factors and gender. Among these, gender, i.e. female sex and physical conditioning prior to, or at the time of beginning training have been consistently identified as important risk factors. Extrinsic risk factors include factors related to physical training, especially volume and intensity of training.1, 2, 4, 5

Stress fractures classically present with gradual onset of localized pain at a typical site following repeated strenuous physical activity. They can be diagnosed clinically, however are confirmed by radiographs. Most stress fractures are managed conservatively. What is more important is the prevention of stress fractures during training, for which broad strategies include various modifications of training. Improving aerobic fitness of trainees prior to training also has a role.4

Stress fractures in military training have been extensively studied in the world including in the Indian Armed Forces, and strategies for prevention being implemented. Most studies in India have been carried out among ‘recruits’ as against ‘cadets’ or ‘officer trainees’. Only one published study is available which was carried out among Air Force cadets including females, in 2000–2004.6 It was therefore felt necessary to study the epidemiology of stress fractures among cadets of the three services, and, to compare it between genders, since it may have implications in prevention. This assumes greater relevance with the increasing and regular induction of females in the Armed Forces in different branches. Consequently, a study was carried out among the ‘officer cadets’ in the training establishments of the Army, Navy and Air Force, where gentlemen and female cadets participated in the same training regimen, to see a gender differential if any.

Material and methods

A large prospective multi-centric study was undertaken to study the epidemiology of stress fractures among male and female cadets in training establishments of the three services during 2011–2012. A single officers training establishment from each of the three services, i.e. Army, Navy and Air Force, where both male and female cadets trained together for their basic training was selected for the purpose of the study. Appropriate approvals from the institutional ethics committee and from the administrative authorities of the establishments were taken for the conduct of the study.

All cadets who joined the institute for training during the study period were included in this study. Baseline data was collected for all the cadets at the beginning of the term (after informed consent), by medical officers at the training institute on a suitably designed validated performa. In addition to personal particulars, it included information on anthropometric parameters and history of physical activity prior to joining training. All the cadets were followed up for the term for development of stress fractures, if any. Detailed information was recorded on a separate questionnaire for those cadets who were diagnosed to have sustained stress fractures as per case definition (radiolologically confirmed by the presence of a fracture or callous). This information covered all important features of stress fracture, i.e. onset, presentation, treatment given and disposal etc., and, was collected from the cadet as well as the medical officer at the training institute. Additional information on various aspects of training, i.e. aspects of physical training, scheduling of events like cross country, equipment, shoes provided, infrastructure available, and the measures in place for reduction of stress fractures at the establishment, was noted by interviewing the administrative authorities. Quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS version 20. A qualitative analysis of all attributes of physical training and measures in place for prevention of stress fractures was also carried out for the three training establishments for comparison.

Results

A total of 3220 cadets (2612 male and 608 female cadets) were included in the study. The baseline data available for 2739 cadets is summarized in Table 1. The mean age for male cadets was 22.7 years and that for female cadets was 22.6 years. Maximum number of cadets, i.e. nearly 50% of male cadets and 60% of female cadets were in the age group 22–24 years. Anthropometrically, the female cadets had significantly lesser height, weight and BMI as compared to the male cadets. A significantly more number of male cadets (63%) as against 48.7% of female cadets gave history of carrying out ‘physical activity’ in the form of brisk walking, running, sports or swimming for more than six months prior to joining the training establishment.

Table 1.

Baseline information on male and female cadets.

| Gentlemen cadets | Lady cadets | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2198) | (n = 541) | ||

| Age in years Mean (SD, 95% CI) |

22.7 (2.0, 22.6–22.7) | 22.6 (1.3, 22.4–22.7) | >0.05 |

| Weight (kg) Mean (SD, 95% CI) |

64.9 (8.5, 64.5–65.2) | 53.7 (8.6, 52.9–54.4) | <0.00 |

| Height (m) Mean (SD, 95% CI) |

1.73 (0.2, 1.72–1.73) | 1.60 (0.37, 1.56–1.63) | <0.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) Mean (SD, 95% CI) |

21.5 (1.8, 21.4–21.5) | 20.7 (1.8, 20.5–20.8) | <0.000 |

| Physical activity, No. (%) | 1366 (63.0) | 265 (48.7) | <0.000 |

Overall, 276 cadets were observed to sustain stress fractures during training, making the combined incidence of stress fractures to be 8.6%. The cumulative incidence for male cadets during the study period was 6.9%, and that for female cadets was 15.8%. The relative risk of sustaining stress fractures during training was 2.29 (p < 0.001) for female cadets in comparison with male cadets.

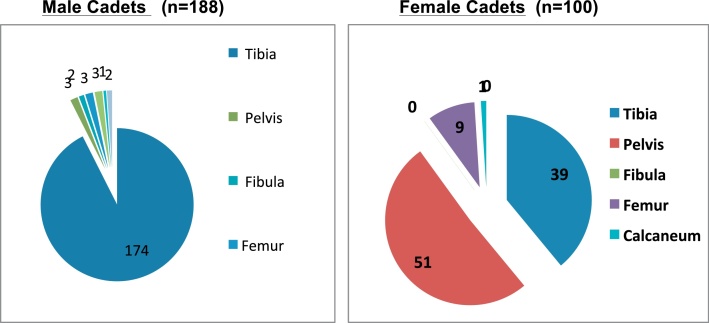

The different types of stress fractures sustained by male and female cadets are as shown in Fig. 1. A total of 188 fractures were observed in 180 male cadets during the study. It is seen that stress fracture tibia was the commonest fracture seen (accounting for >90% of stress fractures), in gentlemen cadets). Among the female cadets, a total 96 female cadets sustained 100 fractures. Fracture pelvis was the commonest fracture sustained (51%) followed by stress fracture tibia (39%).

Fig. 1.

Genderwise distribution of stress fractures sustained.

The various attributes of stress fractures, i.e. clinical presentations, the aggravating and relieving factors and the activity prior to onset for male and female cadets is depicted in Table 2. Clinically, both male and female cadets presented with the symptom of localized pain which was gradually progressive, and difficulty in walking and training. A significantly larger proportion of female cadets (65%) came with history of difficulty in walking as compared to males (49%). Aggravating and relieving factors for cadets of both genders were similar, but a larger number of female cadets (52%) said that they were relieved by hot fomentation (p < 0.05). The most common activity prior to onset of symptoms was running, especially long distance running and drill with boots. Though more number of female cadets gave running or cross country as the activity precipitating the onset of symptoms as compared to males, the difference was not significant. A significant observation was that 61% of the women cadets who sustained stress fractures gave history of ‘delayed periods’ or ‘amenorrhoea’.

Table 2.

Gender differential in various attributes of stress fractures.

| Attribute | Male cadets | Female cadets | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of stress fractures | |||

| No. | 180 | 96 | RR for lady cadets 2.29 1.82–2.86 p < 0.001 |

| (%) | 6.9 | 15.8 | |

| 95% CI | (6.0–7.9) | (13.1–18.9) | |

| Location of stress fractures, No. (%) | |||

| Tibia | 174 (92.5) | 39 (39) | <0.000 |

| Femur | 3 (1.5) | 9 (9) | 0.00 |

| Metatarsal | 391.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Pelvis | 3 (1.5) | 51 (51) | <0.0000 |

| Others | 5 (2.5) | 1 (1) | |

| Clinical presentation, No. (%) | |||

| Pain | 171 (95) | 87 (91) | >0.05 |

| Difficulty in walking | 88 (49) | 62 (65) | <0.05 |

| Difficulty in running | 168 (93) | 87 (91) | >0.05 |

| Difficulty in drill | 149 (83) | 76 (79) | >0.05 |

| Aggravating factors, No. (%) | |||

| Weight bearing | 38 (21) | 21 (21) | >0.05 |

| Walking | 24 (13) | 19 (20) | >0.05 |

| Running | 145 (80) | 71 (74) | >0.05 |

| Drill | 124 (68) | 65 (68) | >0.05 |

| Relieving factors, No. (%) | |||

| Rest | 166(92) | 89 (92.7) | >0.05 |

| Hot fomentation | 43 (23) | 50 (52) | <0.000 |

| Pain killers | 52 (28) | 36 (37.5) | >0.05 |

| Week of training with max onset | 4th (12%) | 9th (18%) | |

| Activity prior to onset, No. (%) | |||

| Drill | 38 (21.1) | 22 (22.9) | >0.05 |

| Running | 96 (53.3) | 59 (61.4) | >0.05 |

| PT | 25 (13.8) | 8 (8.3) | >0.05 |

| Duration of training days lost (in weeks) | 4.5 | 4.8 | |

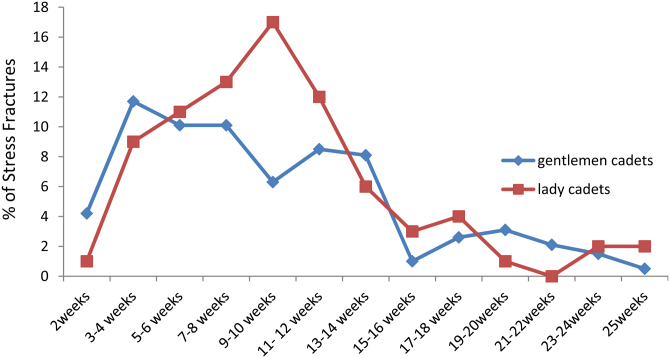

The onset of stress fractures during the 26 weeks of training in male and female cadets was observed to be different as shown in Fig. 2. In male cadets, maximum fractures 13 (6.9%) were reported in the 4th week of training while in the female cadets the maximum stress fractures 13 (13%) were seen in the 9th week of training.

Fig. 2.

Onset of stress fractures among male and female cadets during training.

The clinical features observed among the cadets were similar in both genders. The main features are as shown in Table 3. Rest and pain killers were the mainstay of management in all cases of stress fractures. All female cadets were also given calcium supplementation in all the three training establishments.

Table 3.

Clinical features and management of stress fractures in male and female cadets.

| Attribute | Male cadets | Female cadets | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | |||

| Walks without support | 141 (78) | 74 (77) | >0.05 |

| Walks with support | 26 (14) | 13 (14) | >0.05 |

| Unable to walk | 10 (5,5) | 5 (5) | >0.05 |

| Swelling | 98 (55) | 62 (64) | >0.05 |

| Tenderness | 168 (93) | 81 (84) | <0.05 |

| Management | |||

| Rest | Yes | Yes | |

| Painkillers | Yes | Yes | |

| Calcium supplementation | No | Yes | |

The average time of training lost was 4.5 weeks for male cadets as against 4.9 for female cadets. The measures in place at the training academy in all the three services for stress fracture prevention were similar for male and female cadets.

All the training establishments were committed towards reduction of stress fractures in training and had the necessary infrastructure and equipment. The instructors were aware of the different types of stress fractures in males and females. There were a number of measures in place for stress fracture reduction. The broad measures in place as per the information obtained from the Training Establishments at the time of the study are presented in Table 4. There was no separate training for lady cadets in the initial phase of training across the three services.

Table 4.

Measures in place in training establishments for stress injury reduction.

| Measure | Remark |

|---|---|

| Awareness among instructors regarding different types of stress fractures in both genders | Good |

| Physical conditioning before training in joining instructions | No |

| Differential training in initial 2–4 weeks | Yes |

| Separate training for lady cadets in initial 4 weeks | No |

| Differential running distance of cross country for both genders | Yes |

| Broad measures in place for stress fracture reduction | • Training schedule • Graded increase in exercise • Rest periods • Prompt medical attention |

| Deliberately planned cross training during the week | No |

| Provision of cycles | Yes |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in our country which has compared the epidemiology of stress fractures between military trainees of both genders, who are undergoing the same kind of training, and has brought out significant differences between them. This observation which is across the three services, indicates the possibility of involvement of different factors in the causation of stress fractures in males and females, and is likely to have implications in planning strategies for prevention.

In the present study, the overall incidence of stress fractures among female cadets, i.e. 15.6% (95% CI = 13.1–18.9). was significantly higher than that observed in male cadets – 6.9% (95% CI = 6.0–7.9). with an RR 2.2. In the only other similar study in the country carried out among flight cadets of Air Force by Raju et al. in the five years from 2000 to 2004, this difference between genders was not significant (7.3% in female cadets and 5.8% in male cadets).6

The observation in the present study however has been well corroborated by studies elsewhere in the world. The incidence of stress fractures during U.S. military basic training was found to be significantly higher, i.e. 1.2–11 times higher in female recruits than in male recruits. Data from US and Israeli military-sponsored researchers have also indicated higher rates in women compared with men. Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) also have recorded a significantly higher incidence of stress fractures among women during anti-air craft basic training. Systematic reviews have revealed that this gender difference in the incidence of stress fractures is consistent and more evident in military settings than in athletes.1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10

The higher incidence in women has been attributed mostly to the initial entry level fitness of the recruits, which is lower in women. Specifically, it has been linked to the ability of bone to withstand the sudden, large increases in physical loading due to increase in the intensity, frequency, or volume of impact of loading activities during basic training. Thus when training regimens are equally imposed on men and women, the resultant stress on the less physically fit, would increase the risk of injury.1

It has been observed that the relative contribution of different intrinsic and extrinsic factors in stress fracture causation can be variable in different individuals and genders.11 Systematic reviews have also consistently attributed a higher injury rate in female recruits and athletes to lower aerobic capacity, reduced muscle mass, narrow tibia, wide pelvis, poor energy, calcium and vitamin D intake and low BMI possibly due to interactions with other risk factors such as reduced resistance to fatigue in bones.8, 12, 13 The other risk factors seen to contribute to these injuries among women are history of smoking, excessive alcohol drinking, history of menstrual dysfunction, white race, and anatomical factors such as narrow tibial cortice, narrow pelvis and smaller thigh muscle girth.5 Studies have also implicated the presence of ‘female athlete triad’ comprising of low energy availability, menstrual dysfunction and low bone mineral density in increasing the risk of stress fractures in women.14, 15

The commonest site for stress fractures among male cadets in this study was the tibia (92.5%). This distribution correlates well with other studies both in India and abroad.16, 17 Israeli researchers and other major studies in the world too found that the most prevalent site of fractures in males undergoing military training is generally the tibia.18 This preponderance has been ascribed to training with maximum stress on running, jumping and parade on hard ground which leads to impact transmission up the bone unsupported by fatigued muscles at that point of time.3, 16, 17

The anatomic distribution of stress fractures females was distinctly different from those seen in men in this study. Though fracture tibia formed a large proportion of the stress fractures (39%), fracture pelvis was the commonest site (51%) in female cadets. This observation has not been corroborated in the earlier study by Raju et al. where the distribution was similar in both genders, i.e. stress fracture tibia being the commonest, i.e. 58%, followed by stress fracture pelvis in 28.5%.6

This relative difference in anatomical distribution of stress fractures observed in the current study has been recorded in studies in Israeli defense forces too, who have concluded that pelvic stress fractures are much more common in women in mixed gender training though the overall incidence of stress fractures was much lower than that seen in this study.5, 8

The skeletal site of the stress fracture may vary between men and women in the military, as stated by the Subcommittee on Body Composition, Nutrition, and Health of Military Women in U.S. Female trainees are more likely to develop stress fractures in the upper leg and pelvis. Factors causing this variation may include alterations in stride length (women are encouraged to march and keep the same stride as men, which is longer than what they are accustomed to. The different anatomical distribution has also been attributed to generation of large muscle force at selected locations because of physical activities and its transmission due to anatomical factors.1, 3 In a systematic review by Wentz et al., it has been observed that for their size, women have wider pelvic breadths, which negatively alter loading strains. A wider pelvis alters the angular tilt on the hips and knees, increasing the stress on these bones and on those of the lower leg and foot. This anatomical difference may explain the greater distribution of stress fractures in the pelvis and hip observed in female recruits.8

Regarding onset, the present study observed that stress fractures in women were reported from the 4th week onwards with maximum incidence in the 8th and 9th week (50%), and 60% occurred within 12 weeks of initiation of training. In male cadets, the incidence of fractures showed a different pattern where they were reported from the first week with a maximum incidence in the 4th week and a high incidence from the 3rd to 9th week. Raju et al. in their study also observed that more than 50% of stress fractures occurred in the first ten weeks of training, with maximum incidence in the eighth week for male and female cadets combined.6 In the study by Dash et al., among recruits, the maximum incidence was observed between 9 and 27 weeks of training.17

The activity prior to onset in this study was typically long distance running, and drill with boots in both men and women. More women gave a history of onset following cross country runs. Drill with boots and repeated stamping on hard uneven surface were the immediate causes of onset as observed by Raju et al., possibly due to impact transmission from the surface.6, 16

There was not much difference between the genders in the clinical presentation in our study – history of localized pain initially, present after activity, progressively increasing with activity and constant pain in the later stages. The pain was relieved with rest and hot fomentation. Most cadets, both males and females, reported with difficulty in weight bearing and had localized tenderness at the site. These findings have been universally observed.1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 17

Stress fractures in both genders were diagnosed clinically and confirmed by plain radiographs. They were managed with rest, which meant admission for a limited period and painkillers, followed by gradual resuming of weight bearing and modified physical activity, depending on the clinical condition. The same has been accepted as the standard treatment and practiced all over. Protocols have been developed to ensure healing and reducing loss of training. It is also recommended to maintain fitness during treatment by activities like cycling, swimming, or working out on exercise machines.9, 19

The goal of all research on stress fractures during military training the world over is to minimize these injuries. These differences between genders in the epidemiology of stress fractures may indicate that males and females have to be dealt with differently during training for stress fracture prevention. Gradual increase in exercise in a structured programme, is recommended for better conditioning of cadets. The same was being implemented in all the three academies. However, the observations in the current study imply that women may require more physical conditioning over a longer time to achieve adequate level of conditioning for mixed gender training as has been recommended by some other researchers too.20 Hence, their training for initial few weeks may be separate from the men, and their long distance runs may be more spaced out.

Periodization of training, i.e. a period of complete rest from high impact activities for a week especially in the third/fourth week and repeated thereafter is another recommended measure to reduce stress fractures in military training.20, 21 The gender difference observed in the time of onset of stress fractures in this study may be a case in point for planning keeping in mind the high risk periods for men and women. Attention also needs to be given to women regarding energy intake and menstrual disturbances if any.4 Further studies are required to be carried out on this aspect.

Conclusion

The findings of the study indicate a clear distinction between the stress fractures sustained by men and women trainees undergoing military training in terms of incidence, location and onset. These gender differences which have emerged may be attributed to differential role of various risk factors. These observations have implications in planning for prevention of stress injuries in men and women trainees. While the broad strategies remain the same, they also indicate that special consideration needs to be given to women trainees. Medical personnel, those involved in training, and the trainees themselves need to be aware of these differences for implementation of various measures in our Training Institutes. Further studies are required to be carried out on the subject and on the effect of interventions in stress fracture prevention in males and females during military training in our country.

Limitations

The study being a large multi-centric study, suffered from the limitation of data in certain important aspects of baseline information in respect of the cadets. Hence the study could not bring out the role of different risk factors in stress fracture causation in male and female cadets.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgement

(a) This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No 4081/2010, granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India. (b) We also sincerely acknowledge the contribution of Surg Cdr Kamal Deep and Wg Cdr S.P. Singh (Retd) at the Training institutes of the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force respectively, in the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Reducing Stress Fracture in Physically Active Military Women . National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1998. Subcommittee on Body Composition, Nutrition, and Health of Military Women, Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Institute of Medicine. ISBN: 0-309-59189-9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pegrum J., Crisp T., Padhiar N. Diagnosis and management of bone stress injuries of the lower limb in athletes. BMJ. 2012;344:e2511. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedl K.E., Evans R.K., Moran D.S. Stress fracture and military medical readiness: bridging basic and applied research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181892d53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones B.H., Thacker S.B., Gilchrist J., Kimsey C.D., Sosin D.J. Prevention of lower extremity stress fractures in athletes and soldiers: a systematic review. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24:228–247. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer R.A., Rauh M.J., Brodine S.K., Trone D.W., Macera C.A. Naval Health Research Center; San Diego, CA: 2004. Predictors of Stress Fracture Susceptibility in Young Female Recruits. Report No. 04-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raju K.S., Sharma S., Yadav R.C., Singh M.V. An epidemiological study of stress fractures among flight cadets at Air Force Academy. Ind J Aerosp Med. 2005;49(1):48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knapik J., Montain S.J., McGraw S., Grier T., Ely M., Jones B.H. Stress fracture risk factors in basic combat training. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(11):940–946. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentz L., Liu P.Y., Haymes E., Llich J. Females have a greater incidence of stress fractures than males in both military and athletic populations: a systemic review. Mil Med. 2011;176(4):420. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruckner P., Bradshaw C., Bennel K. Managing common stress fractures: let risk level guide treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 1998;26(8):39–47. doi: 10.3810/psm.1998.08.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennell K.L., Brukner P.D. Epidemiology and site specificity of stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16(2):179–196. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warden S.J., Burr D.B., Brukner P.D. Stress fractures: pathophysiology, epidemiology, and risk factors. Curr Osteopor Rep. 2006;4:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s11914-996-0029-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loud K., Gordon C., Micheli L., Field A. Correlates of stress fractures among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e399–e406. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck T.J., Ruff C.B., Shaffer R.A., Betsinger K., Trone D.W., Brodine S.K. Stress fracture in military recruits: gender differences in muscle and bone susceptibility factors. Bone. 2000;27(3):437–444. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nattiv A., Loucks A.B., Manore M.M., Sanborn C.F., Sundgot-Borgen J., Warren M.P. American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(10):1867. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318149f111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Souza M.J., Nattiv A., Joy E. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:289. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal P.K. Stress fractures – management using a new classification. Indian J Orthop. 2004;38(2):118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dash N., Kushwaha A.S. Stress fractures—a prospective study amongst recruits. MJAFI. 2012;68(2):118–122. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hod N., Ashkenazi I., Levi Y. Characteristics of skeletal stress fractures in female military recruits of the Israel defense forces on bone scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31(12):742–749. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000246632.11440.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duckham R.L., Peirce N., Meyer C. Risk factors for stress fractures in female endurance athletes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001920. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orr R., Johnston V., Coyle J., Pope R. Load carriage and the female soldier. J Mil Vet Health. 2011;19(3):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Khawashki H. Stress fractures in athletes: A literature review. Saudi J Sports Med. 2015;15:123–126. [Google Scholar]