Introduction

Prurigo pigmentosa (PP) is an uncommon, acquired inflammatory disorder with a predilection for young adults of Asian descent.1 This condition is manifested by highly pruritic, reticulated, and erythematous papules that resolve with hyperpigmentation.2 Multiple cases of PP have been reported since its initial description in 1971 by Nagashima et al3; however, this dermatosis is still underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.3, 4, 5, 6 The most significant challenge limiting the identification of PP is successful distinction from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). Herein, 2 patients with PP are described, with a focus on differentiating features from CARP.

Case series

Patient 1

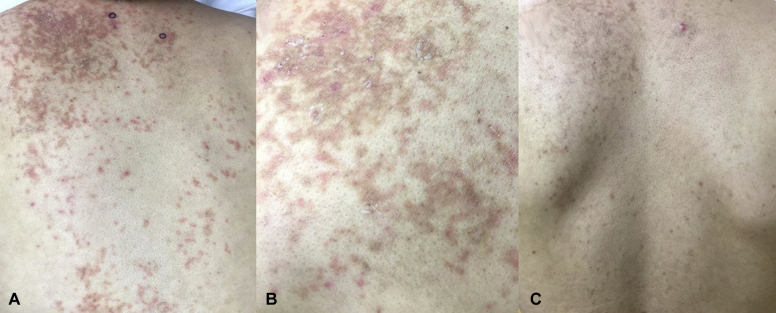

A 30-year-old Chinese man presented with reticulated erythematous and hyperpigmented papules on his back and shoulders (Fig 1, A and B). The eruption was present for 2 weeks and was associated with severe pruritus. Histopathologic evaluation of a punch biopsy found a subacute spongiotic dermatitis with dyskeratosis (Fig 2, A and B). After treatment with minocycline, 100 mg, and halobetasol 0.05% ointment, both twice daily for 6 weeks, the erythema and pruritus resolved, but hyperpigmentation was persistent (Fig 1, C).

Fig 1.

A, Reticulated erythematous and hyperpigmented papules on the back of an Asian man. B, Fine scale is evident and most of the papules are erythematous in the acute stage; the eruption was present for 3 weeks. C, After treatment with minocycline and halobetasol for 6 weeks, the erythematous papules resolved but reticulate hyperpigmentation was persistent.

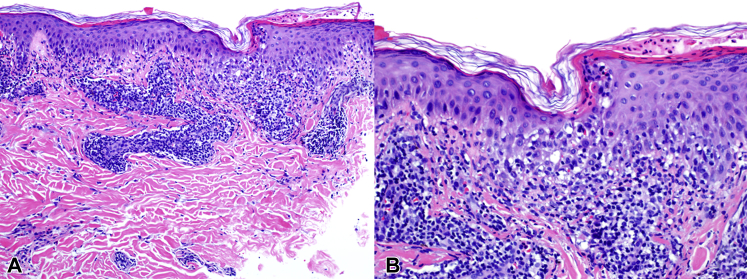

Fig 2.

A, Subacute spongiotic dermatitis with a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. B, Dyskeratosis, lymphocyte exocytosis, and Langerhans cell microabscesses are evident. (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: A, ×100; B, ×200.)

Patient 2

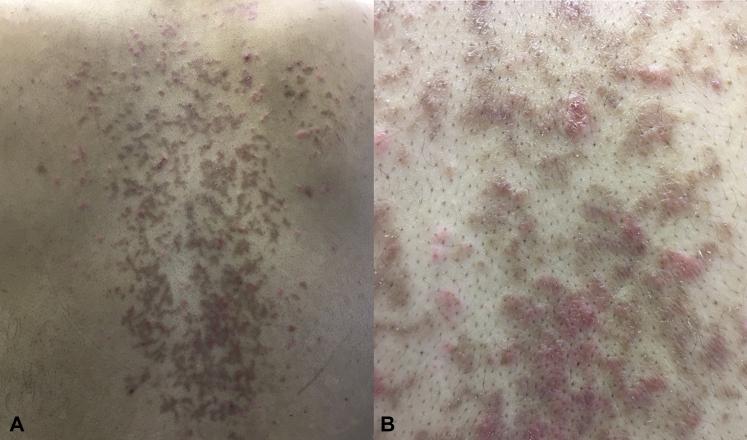

A 31-year-old Indian man presented with a pruritic reticulated eruption on the back, chest, and chin. At the time of presentation, the eruption was present for 3 months and was composed largely of hyperpigmented papules (Fig 3, A and B). Prior treatment with topical hydrocortisone was unsuccessful. Similar to the histopathologic findings observed in patient 1, a punch biopsy found a subacute spongiotic dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes and pigment incontinence. After treatment with minocycline, 100 mg, and halobetasol 0.05% ointment, both twice daily for 4 weeks, the papular pruritic lesions resolved, but hyperpigmentation was persistent.

Fig 3.

A, Reticulated erythematous and hyperpigmented papules and plaques with confluence on the back of an Indian man. B, The majority of the papules are hyperpigmented at this stage, several months after onset.

Discussion

PP presents with a reticulated morphology, with erythema and pruritus dominating the acute stage and hyperpigmentation predominant in the chronic stage; coexistence of stages is frequent.5, 7 CARP is also manifested by hyperpigmented papules with a netlike appearance and a predilection for the trunk and proximal extremities.8 PP and CARP have overlapping clinical morphology, and PP may be clinically diagnosed as CARP given the rarity of the former compared with the latter diagnosis.7 Recently, a case was reported with features of both PP and CARP, suggesting that these conditions may represent a spectrum rather than separate entities.7 However, distinction is facilitated by demographic information, clinical morphology in the acute stage of PP, histopathology, treatment outcomes, and prognosis. These differentiating features are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

| Demographic | Clinical morphology | Symptoms | Histology | Treatment | Prognosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | Most common in Asian patients and dark-skinned races; rare in whites | Acute: papular, vesicular, or urticarial erythematous eruption with reticulated appearance on chest and back Chronic: reticulated hyperpigmentation |

Severe pruritus ± burning sensation in acute stage | Acute: acute or subacute spongiosis with dyskeratosis ± subcorneal or intraepidermal pustules Chronic: pigment incontinence and sparse dermal lymphocytic infiltrate |

Minocycline, doxycycline, tetracycline, dapsone, topical steroids | Acute findings of pruritus and papular or vesicular lesions resolve with treatment; hyperpigmentation persists for months to years |

| CARP | Occurs in all ethnicities including whites | Scaly, hyperpigmented papules with central confluence and peripheral reticulation on the chest, back, neck, axillae, and occasionally proximal extremities | Asymptomatic in majority; when present, pruritus is mild | Hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, basilar hyperpigmentation, follicular plugging, flattening of rete ridges | Minocycline, doxycycline, azithromycin, erythromycin, isotretinoin, topical tretinoin, tazarotene, topical steroids | Chronic course with frequent recurrence after discontinuation of therapy; no persistent dyspigmentation |

CARP, Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis; PP, prurigo pigmentosa.

Compared with PP, CARP also occurs in dark-skinned patients but is more common in white patients, with presentation between the ages of 8 and 32 years and a male-to-female ratio of 1.4 to 2.6:1.8 In contrast, PP is more common in Asian patients, particularly those from China and Japan, affects females more often than males (4-6:1), and usually presents in individuals in their 20s.1, 5, 6

CARP shows central confluence and peripheral reticulation and is composed of hyperpigmented scaly papules, sometimes with an ichthyosiform appearance. The preferred sites of involvement are the upper trunk (particularly the interscapular and intermammary skin), neck, and axillae.7 In contrast, PP evolves from initially erythematous papules or papulovesicles into hyperpigmented macules later. Although the chest and back are similarly involved in PP and CARP, PP tends to spare the neck and axillae.1, 2, 8 Although PP is associated with significant and often severe pruritus, most patients with CARP are asymptomatic.2, 8, 9

Histologically, CARP is characterized by hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and basilar pigmentation—the findings of acanthosis nigricans. In contrast, PP shows spongiosis with vesiculation, dyskeratosis, and sometimes subcorneal or intraepidermal neutrophilic abscesses in its acute stage. Vacuolar change is infrequent. A chronic stage is characterized by a sparse perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with marked pigment incontinence. Analogous to the clinical findings of PP, the histologic stages may overlap.2, 7, 9

The first-line therapy for both PP and CARP is minocycline. Second-line treatments for CARP include macrolide antibiotics, such as azithromycin, whereas dapsone may be used as an alternative for PP. Antibiotics are useful in both diseases because of their anti-inflammatory properties, possibly relating to inhibition of neutrophil migration and oxygen release.1, 9 In CARP, topical tretinoin and tazarotene and oral isotretinoin have been used in minocycline-refractory cases.8 Topical corticosteroids are of limited efficacy in CARP and PP but may be used as adjunctive treatment for pruritus in PP.5, 6, 7 Although the acute lesions of PP subside after treatment, leaving residual hyperpigmentation that persists for months to years, CARP is characterized by a chronic course with recurrences after discontinuation of therapy. However, once resolution of scaling papules is achieved in CARP, persistent hyperpigmentation is not characteristic.8, 9

PP and CARP are both acquired dermatoses of unknown etiology that affect young adults, present with reticulated papules distributed on the trunk, and respond quickly to treatment with minocycline. Discrimination is permitted by attention to demographics, morphology in early or acute disease, histopathologic findings, and the presence or absence of persistent hyperpigmentation after treatment.

Footnotes

Funding sources: The article processing fee for this manuscript will be paid by the Open Access Publishing Fund at the University of Florida (details: http://cms.uflib.ufl.edu/ScholComm/UFOAPF).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Corley S.B., Mauro P.M. Erythematous papules evolving into reticulated hyperpigmentation on the trunk: a case of prurigo pigmentosa. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böer A., Misago N., Wolter M., Kiryu H., Wang X.D., Ackerman A.B. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25(2):117–129. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagashima M., Ohshiro A., Schimuzu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38–39. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeunon de Sousa Vargas T., Abreu Raposo C.M., Lima R.B., Sampaio A.L., Bordin A.B., Jeunon Sousa M.A. Prurigo pigmentosa–report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(4):267–274. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng X., Li L., Cui B.N. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinical and histopathological study of nine Chinese cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1794–1798. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hijazi M., Kehdy J., Kibbi A.G., Ghosn S. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 4 cases from the Middle East. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(10):800–806. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilkovitch D., Patton T.J. Is prurigo pigmentosa an inflammatory version of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(4):e193–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim J.H., Tey H.L., Chong W.S. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:217–223. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S92051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Min Z.S., Tan C., Xu P., Zhu W.Y. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis manifested as vertically rippled and keratotic plaques. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31(5):335–337. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.44011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]