Introduction

The etiology of crowding is the disproportion between tooth material and jaw size. It may be either due to increased mesiodistal widths of teeth or smaller jaws or their combination. Whenever there is insufficient space for the teeth to fit in the jaws, they may be displaced or rotated.1, 2 The insufficient space for teeth can be gained by extraction, expansion or proximal stripping. The management of crowding is not always a cook book approach. It may be associated with certain factors which complicate the treatment progress like periodontitis, impacted teeth, medically compromised patients, decayed teeth, uncooperative patient etc. The treatment plan and biomechanics have to be modified depending upon the complicating factor. For periodontally compromised teeth, the force applied should be minimum, light and constant.3, 4 The center of resistance of a periodontally compromised tooth shifts apically and produces more pressure and moments (rotational tendency), which complicate the biomechanics.5, 6 Apical shift of center of resistance of a tooth and the moments generated due to a force are directly proportional to the amount of alveolar bone loss. Self-drilling implants have been recommended to be a preferred choice for providing anchorage in periodontally compromised dentitions.

Case report

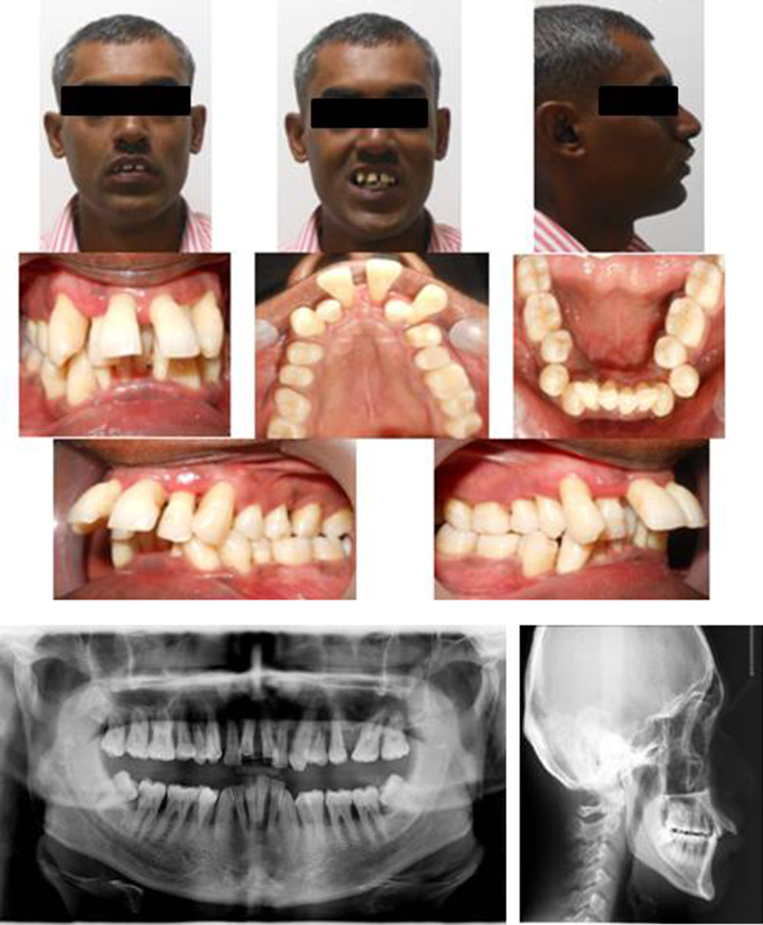

A 34-year-old patient reported with a chief complaint of long, irregular, front positioning of teeth with speech difficulties. He had a history of generalized aggressive periodontitis that had been treated over an 8-month period with subgingival scaling and root planning, followed by regular periodontal maintenance. Maxillary left first molar (26) was extracted due to periodontal involvement. Maxillary central incisors (11, 21) were excessively extruded and proclined with grade 2 mobility. He had severe generalized bone loss and gingival recession, but the condition was stable and non-progressive, when he reported for orthodontic treatment. He had difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene due to severe crowding and was also psychologically depressed due to poor facial esthetics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pretreatment photographs, OPG and lateral cephalogram.

Diagnosis

Calculus deposits, gingival inflammation, severe gingival recession, severe bone loss, stable and non-progressive generalized periodontitis, history of extraction of 26, cariously exposed mandibular right second molar (47), convex profile, lip incompetence, lower lip trap, increased upper incisor visibility, upper midline diastema, U/L severe crowding, maxillary arch constriction, crossbite of maxillary left second and third molar (27, 28), increased overjet (15 mm), upper proclined incisors, molar relation (class I on right side and non-specific on left side), mesial shifting of 27, deep curve of spee, deep bite, average growth pattern.

Treatment objectives

To maintain good oral hygiene, improve facial profile, leveling and alignment, to reduce overjet, to level curve of spee, to achieve acceptable occlusion, intrusion, and retraction of anterior teeth.

Treatment plan

-

-

Necessary blood investigations – NAD

-

-

Consent form was signed by the patient

-

-

Periodontal treatment, including scaling and root planning, before intrusion and retraction of anterior teeth

-

-

RCT of 47

-

-

Therapeutic extraction of four first premolars (14, 24, 34, 44)

-

-

Maximum anchorage with self-drilling implants in the premolar-molar region

-

-

Fixed appliance – 018″ Roth Preadjusted edgewise appliance (PEA)

-

-

Retention – fixed lingual retainer from premolar to premolar

Treatment progress

Scaling and root planning, with motivation of the patient were carried out. Chlorhexidine mouth wash was prescribed. Consent was obtained from the patient regarding treatment for the poor prognosis of upper central incisors. Occlusal stop in the form of glass ionomer cement was placed to prevent occlusal interferences for bonding of lower anteriors. Alignment and leveling were carried out after extraction, and simultaneously four 1.5 mm × 8 mm self drilling implants (Arrow I, Silver line series, Classic Orthodontics) were placed in premolar-molar area of both the arches to prevent labial force on incisors. Sectional 016 × 022″ SS arch wires were engaged separately for anterior and posterior sections. Niti closed coil springs from implants to anterior sections were engaged for simultaneous intrusion and retraction of anterior teeth (Fig. 2). Force was kept minimum keeping in mind the periodontal condition and was directed in a posterior and superior direction. During treatment, the patient received monthly reinforcement of plaque removal and subgingival debridement at 3-month intervals as recommended by Vanarsdall. Spaces were closed in 14 months followed by settling of occlusion. Fixed lingual retainers were bonded with 016″ heat treated coaxial wire. The total treatment time was 17 months. Comparison of pre- and post-treatment photographs showed marked improvement in facial profile and esthetics, intrusion, and retraction of anterior teeth, decrease in overjet, leveling of curve of spee, improvement in oral hygiene, and bone loss (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Midtreatment photographs (after 7 months).

Fig. 3.

Post-treatment photographs, OPG and lateral cephalogram superimposition.

Discussion

The problems in the case shown here were migration, elongation, mobility, and spacing of the incisors. These changes took place due to imbalance between the available periodontal support and the forces acting on the teeth. It led to trauma from occlusion that further enhanced the periodontal destruction in the presence of plaque associated inflammatory lesion of the gingiva. Elongated lower incisors (deep curve of spee) applied force in a labial direction to upper incisors contributing to further flaring of incisors.

With progressive bone loss, the center of resistance moved apically and the forces acting on the crowns generated a larger moment, adding to the progressive displacement. Since 11 and 21 were mobile, elongated, excessive labial flaring with alveolar bone support only up to the apical third of the roots, a consent form was signed by the patient regarding the poor prognosis of incisors. During intrusion of teeth, patient was able to maintain his good oral hygiene. The force was applied through Niti closed coil spring from implants, and immediate loading of implants was done.

Before starting orthodontic treatment, good oral hygiene was achieved under the supervision of periodontist. Melsen7, 8 in her study advised eliminating deep pockets and plaque before attempting any tooth movement especially intrusion so as to prevent any apical movement of bacteria in plaque. Apical movement of plaque during intrusion may further worsen the case of periodontitis. Therefore, our patient was given a similar treatment as advised by Melsen. No/minimal root resorption was observed after completion of treatment.

Conclusion

The success of managing a case of severe crowding requires thorough diagnosis and treatment planning. The complicating factor associated with crowding may prolong the total treatment time and the final outcome. Patient compliance also plays a very important role in the success of treatment. Orthodontic intrusion may cause severe root resorption in some cases. Force applied in periodontally compromised cases should be light, constant, continuous, and in a desired direction.

Conflict of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Bishara S.E. vol. 13. 2001. pp. 146–184. (Textbook of Orthodontics. An Approach to the Diagnosis of Different Malocclusion). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proffit W.R., Fields H.W., Jr. Orthodontic treatment planning: from problem list to specific plan. In: Proffit W.R., editor. 5th ed. vol. 7. Mosby; North Carolina: 2013. pp. 220–266. (Contemporary Orthodontics). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd R.L., Leggot P.J., Quinn R.S. Periodontal implications of orthodontic treatment in adults with reduced or normal periodontal tissues versus those of adolescents. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1989;96:191–198. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90455-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thilander B. The role of the orthodontist in the multidisciplinary approach to periodontal therapy. Int Dent J. 1986;36:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusy R.P., Tulloch J.F. Analysis of moment/force ratios in the mechanics of tooth movement. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1986;90:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(86)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller B.H. Orthodontics for the adult patient. Part 2 – the orthodontic role in periodontal, occlusal and restorative problems. Br Dent J. 1980;148:128–132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melsen B., Agerbaek N., Markenstam G. Intrusion of incisors in adult patients with marginal bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1989;96:232–241. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melsen B. Tissue reaction following application of extrusive and intrusive forces to teeth in adult monkeys. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1986;89:469–475. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(86)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]