Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the reproducibility of the three main classifications of ankle fractures most commonly used in emergency clinical practice: Lauge-Hansen, Danis-Weber, and AO-OTA. The secondary objective was to assess whether the level of professional experience influenced the interobserver agreement for the classification of this pathology.

Methods

The study included 83 digitized preoperative radiographic images of ankle fractures, in anteroposterior and lateral views, of different adults that had occurred between January and December 2013. For sample calculation, the estimated accuracy was approximately 15%, with a sampling error of 5% and a sampling power of 80%. The images were analyzed and classified by six different observers: two foot and ankle surgeons, two general orthopedic surgeons, and two-second-year residents in orthopedics and traumatology. The Kappa statistical method of multiple variances was used to assess the variations.

Results

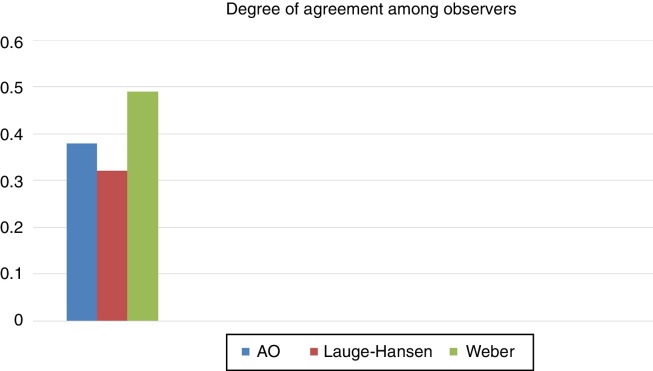

The Danis-Weber classification indicated that 40% of the agreements among all observers were good or excellent, whereas only 20% of good and excellent agreements were obtained using the AO and Lauge Hansen classifications. The Kappa index was 0.49 for the Danis-Weber classification, 0.32 for Lauge Hansen, and 0.38 for AO.

Conclusion

The Hansen-Lauge classification presented the poorest interobserver agreement among the three systems. The AO classification demonstrated a moderate agreement and the Danis-Weber classification presented an excellent interobserver agreement index, regardless of professional experience.

Keywords: Ankle injuries, Observer variation, Ankle fracture/classification

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar a reprodutibilidade e comparatividade das três principais classificações usadas para fraturas do tornozelo mais comumente empregadas nos servicos de emergência: Lauge-Hansen, Danis-Weber e AO-OTA. Observar secundariamente se existe influência da experiência profissional sobre a concordância entre observadores para a classificação dessa patologia.

Métodos

Foram usadas 83 imagens digitalizadas de radiografias pré-operatórias, em incidências anteroposterior e perfil, de fraturas do tornozelo de adultos diferentes, ocorridas entre janeiro e dezembro de 2013. No cálculo amostral assumiu-se precisão da estimativa de 15%, com erro amostral de 5% e com poder de amostragem de 80%. A leitura e a classificação das fraturas foram feitas por seis observadores, dois cirurgiões de pé e tornozelo, dois ortopedistas generalistas e dois residentes do segundo ano de ortopedia e traumatologia. A análise das variações foi feita pelo método estatístico de Kappa de múltiplas variâncias.

Resultados

Com o uso da classificação de Danis-Weber, 40% das concordâncias foram consideradas boas ou excelentes entre todos os observadores, enquanto nas classificações de Lauge Hansen e AO apenas 20% se apresentaram boas ou excelentes. O índice Kappa acumulado para cada classificação foi de 0,49 para a classificação de Danis-Weber, 0,32 para Lauge Hansen e 0,38 para a classificação AO.

Conclusão

A classificação de Lauge Hansen apresenta a pior concordância interobservador dentre as três classificações. A classificação da AO demonstrou concordância intermediária e a de Danis-Weber apresentou o maior índice de concordância interobservador, independentemente da experiência do profissional.

Palavras-chave: Traumatismos do tornozelo, Variações dependentes do observador, Fraturas do tornozelo/classificação

Introduction

Ankle injuries account for 5 million emergency department visits in the United States, 85% of which are sprains and the remaining 15%, fractures. Ankle fractures are among the most common injuries treated by orthopedic surgeons; they account for 9% of all fractures and 36% of all lower limb fractures, generating an annual cost of US$ 10 billion per year in that country. These injuries tend to have a bimodal distribution, peaking in young men and elderly women. Incidence in elderly women has tripled in the last 30 years, due to population aging.1 The treatment of these fractures depends on the careful identification of the extent of bone lesions, as well as the damage to the soft tissues and ligaments. The assessment of a suspected ankle fracture includes detailed medical history, physical examination, appropriate radiographic examination, and initial treatment options. Once the fracture has been well defined, the key to a successful outcome lies in the anatomical restoration of the structures involved for tibiotalar joint reconstruction.2

The first classification methodology for ankle fractures was developed by Percival Pott apud Budny and Young,1 which described the number of fractured malleoli, stratifying the lesions as unimalleolar, bimalleolar, or trimalleolar. Although this classification is intuitive and easy to reproduce, it does not distinguish stable and unstable injuries, nor does it guide treatment.3

Lauge-Hansen,4 through cadaveric experiments, proposed a classification system that correlates the lines of ankle fractures with certain trauma mechanisms. The fractures are classified into four groups: supination-adduction, supination-eversion, pronation-eversion, and pronation-abduction. The first term indicates the position of the foot at the time of injury and the second refers to the direction of the force applied to the foot at the time of the trauma.4, 5, 6 According to this classification, the supine-eversion pattern is the most frequent in emergency departments, with a prevalence ranging from 40% to 75%.7

Danis8 and Weber9 proposed another classification system based on the localization of the main fibular fracture line, dividing the fractures into three groups: type A (below the syndesmosis level), type B (at the syndesmosis level), and type C (above the syndesmosis). Despite its simplicity and ease-of-reproduction, this classification does not consistently predict the extent of the injury in the tibiofibular syndesmosis, as several studies have already demonstrated, since type B and C fractures can be treated in a similar way regardless of the location, according to the presence or absence of ligament instability at the site. This classification also disregards the state of the structures on the medial side, a vital osteoligament structure, and it is not possible to compare prognosis, treatment, or evolution of the pathology with this classification alone.10, 11

The AO-OTA group expanded the Danis-Weber classification scheme, developing a classification based on the location of the fracture lines and on the degree of comminution. Thus, it allows describing the severity and degree of instability associated with a specific fracture pattern.12, 13 Although it is more comprehensive, the AO-OTA classification still presents limited inter and intraobserver reliability.14, 15

Although studies have compared the advantages and disadvantages of several classifications, the authors believe that it is necessary to study a simultaneous analysis of the reproducibility of these three classifications (Lauge Hansen, Danis-Weber, and AO-OTA), because they are the most commonly used classifications in the clinical practice of emergency services in Brazil, which is of paramount importance for communications between physicians and emergency services, especially in resident training institutions, and to some extent collaborate in directing the treatment of these injuries.

The present study aimed to quantitatively determine the level of interobserver agreement of the aforementioned classifications for ankle fractures through the reading of digitalized ankle fracture images by six observers with different levels of specialization: two foot and ankle surgeons, two general orthopedic surgeons, and two second year residents in orthopedics and traumatology.

Secondly, the agreement of each of the three classifications among the observers was studied, in order to verify whether the degree of expertise or experience of the observers influenced the agreement among the observers.

Materials and methods

For the sample calculation, a precision of 15% was estimated, with a sampling error of 5% and with a sampling power of 80%, leading to the number of 80 images to be analyzed.

A total of 83 digitalized images of preoperative radiographs were obtained, in anteroposterior and lateral views, standardized according to the standard radiographic technique of image acquisition.11

Images of ankle fractures were obtained from the first 100 patients with an ankle fracture diagnosis attended to at the emergency department between January and December 2013.

The inclusion criteria were: isolated ankle fractures observed in two radiographic views (anteroposterior and lateral) of adult patients of both genders and who allowed the use of their radiographic material in the experiment. Polytraumatized patients, those under 18 years, and those who did not allow the use of their radiographic material were excluded.

The standard radiographic images were digitalized with a 12-megapixel camera. The digitalized images were analyzed independently by the examiners, under identical conditions.

Six observers of three types of expertise in orthopedics and traumatology were invited to participate in the study: two foot and ankle surgeons (identified by numbers 1 and 2), two general orthopedic surgeons who work daily in the emergency room (identified by numbers 3 and 4), and two second year residents of the Hospital's Orthopedics and Traumatology Program (identified by numbers 5 and 6).

Each observer was asked to determine to which category each of the fractures would belong, according to the following classifications:

-

-

Lauge-Hansen: supination-adduction (SA), supination-external rotation (SER), pronation-abduction (PA), pronation-external rotation (PRE).

-

-

Danis-Weber: A (below the syndesmosis), B (at the level of the syndesmosis), and C (above the syndesmosis).

-

-

AO-OTA: A1 (isolated infrasyndesmotic fibular fracture), A2 (infrasyndesmotic fibular fracture with fractured medial malleolus), A3 (infrasyndesmotic fibular fracture with posteromedial fracture), B1 (isolated transsyndesmotic fibular fracture), B2 (transsyndesmotic fibular fracture with medial lesion, fracture of the medial malleolus or of the deltoid ligament), B3 (transsyndesmotic fibular fracture with medial lesion and posterior malleolus lesion), C1 (simple suprasyndesmotic fibular fracture), C2 (multifragmentary suprasyndesmotic fibular fracture), C3 (proximal fibular fracture – Maisonneuve fracture).

Interobserver variations were analyzed using the Kappa method,16 which evaluates the concordance between observers through paired analysis, compares the observed proportion of agreement between observers (Po) with the percentage of agreement expected by chance (Pe). The values could range from −1.0 (complete discordance) to +1.0 (complete agreement). With this scale, the value zero represents the agreement expected by chance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of the strength of agreement according to the Kappa coefficient.

| Kappa coefficient | Strength of agreement |

|---|---|

| Less than 0 | Negligible |

| 0.00–0.20 | Poor |

| 0.21–0.40 | Fair |

| 0.41–0.60 | Moderate |

| 0.61–0.80 | Good |

| 0.81–1.00 | Excellent |

Source: Landis and Koch.17

Results

The classification of the 83 digitalized images of ankle fracture radiographs by the six examiners were analyzed. Regarding the Danis-Weber classification, most fractures were classified as type B (67.62%), followed by type C (23.81%), and type A (8.57%).

The AO classification presented a total predominance similar to that of Danis-Weber; 67.85% of the fractures were classified as subdivisions of type B (B1 = 26.90%, B2 = 27.38%, and B3 = 13.57%). Type C subdivisions corresponded to 23.56% of all fractures (C1 = 6.90%, C2 = 11.90%, and C3 = 4.76%) and type A, 8.57% (A1 = 2.86%, A2 = 4.76%, and A3 = 0.95%).

Regarding the Lauge-Hansen classification, a predominance of supination-eversion (60.48% of cases) was observed, followed by pronation-eversion (20.95%), pronation-abduction (12.86%), and finally supination-adduction (5.71%).

Of the 83 digitalized images, 70 (84.33%) presented lateral malleolus fractures (unimalleolar, bimalleolar, or trimalleolar), six showed (7.2%) fractures isolated of the medial malleolus, and one (1.2%) showed isolated fracture of the posterior malleolus.

Thirteen images were considered as non-classifiable by at least one observer. These were isolated medial malleolar fractures and posterior malleolar fractures, and were thus considered only by examiners 5 and 6 when using the AO classification.

Using the classification criteria for the Kappa coefficient, as proposed by Landis and Kock17 (Table 1), the percentage of agreement and the Kappa index for the assessments of the six observers were evaluated.

In the Danis-Weber classification, 40% of the assessments presented good or excellent agreement among all the observers, whereas in the Lauge Hansen and AO classifications only 20% of the assessments presented good or excellent agreement. The accumulated Kappa index was 0.49 for the Danis-Weber classification, 0.32 for Lauge-Hansen, and 0.38 for the AO classification, as shown in Fig. 1. Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 present the degree of agreement observed in the assessments using the Danis-Weber, Lauge-Hansen, and AO classifications, respectively, combining the results of all observers.

Fig. 1.

Degree of agreement among observers in each of the classifications: AO, Lauge-Hansen, and Danis-Weber.

Table 2.

Kappa value – Weber classification.

| Kappa | Z | |

|---|---|---|

| Type A | 0.12 | 4.05 |

| Type B | 0.49 | 16.05 |

| Type C | 0.64 | 21.01 |

| Combined | 0.49 | 19.98 |

Table 3.

Kappa value – Lauge-Hansen classification.

| Trauma mechanisms | Kappa | Z |

|---|---|---|

| Supination-adduction | 0.32 | 10.50 |

| Supination-eversion | 0.24 | 8.05 |

| Pronation-abduction | 0.32 | 10.67 |

| Pronation-eversion | 0.38 | 12.44 |

| Combined | 0.32 | 16.67 |

Table 4.

Kappa value – AO classification.

| AO subtypes | Kappa | Z |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | −0.02 | −0.95 |

| A2 | 0.47 | 15.53 |

| A3 | 0.26 | 8.64 |

| B1 | 0.18 | 5.87 |

| B2 | 0.34 | 11.06 |

| B3 | 0.53 | 17.40 |

| C1 | 0.009 | −0.31 |

| C2 | 0.41 | 13.33 |

| C3 | 0.47 | 15.39 |

| Combined | 0.38 | 27.40 |

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 present the Kappa indices paired between the different observers using the Danis-Weber, Lauge-Hansen, and AO classifications, respectively.

Table 5.

Presentation of the Kappa index between the assessments made by the six observers for the Danis-Weber classification.

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | X | 0.24 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.93 |

| O2 | 0.24 | X | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| O3 | 0.75 | 0.28 | X | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| O4 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.50 | X | 0.44 | 0.43 |

| O5 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 0.92 | 0.44 | X | 0.81 |

| O6 | 0.93 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.43 | 0.81 | X |

Table 6.

Presentation of the Kappa index between the assessments made by the six observers for the Lauge-Hansen classification.

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | X | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| O2 | 0.30 | X | 0.17 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| O3 | 0.27 | 0.17 | X | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| O4 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.31 | X | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| O5 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.31 | 1.00 | X | 1.00 |

| O6 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 1.00 | X |

Table 7.

Presentation of the Kappa index between the assessments made by the six observers for the AO classification.

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | X | 0.17 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.58 | 0.78 |

| O2 | 0.17 | X | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| O3 | 0.63 | 0.17 | X | 0.34 | 0.71 | 0.61 |

| O4 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.34 | X | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| O5 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.33 | X | 0.57 |

| O6 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.57 | X |

Discussion

This study assessed the interobserver reproducibility of the three most commonly used classifications for ankle fractures in Brazil.

A good interobserver agreement was observed in the comparison of the evaluations using the Danis-Weber classification, which demonstrated good reproducibility, especially in cases in which the main fracture line was above the syndesmosis level. This finding was consistent among most observers, especially among residents and orthopedists who work daily in the hospital emergency room.

Regarding the Danis-Weber classification, the presence of more objective and easily identifiable criteria for its use in the common radiographic examination (as it only takes into account the level of the fracture line in the fibula) allows a greater ease in the application and greater agreement among examiners.

In the Lauge-Hansen and AO rankings, there is greater complexity in the evaluation criteria, as they require some degree of subjectivity. Lauge-Hansen's method requires the examiner to reconstruct the trauma mechanism through the clinical history and the radiographs. This classification can originate similar radiographic images from completely different trauma mechanisms, such as the initial stages of pronation-abduction fractures and pronation-eversion fractures, which may lead to a greater diagnostic imprecision.18 In the present study, a poor agreement was observed among most examiners, as already demonstrated in previous studies by Budny and Young,1 who presented an interobserver correlation ranging from 61% to 64%.18 However, an excellent agreement was observed among the residents in the present study (K = 1.00). The authors believe that the agreement between these professionals-in-training is due to their greater homogeneity of knowledge in relation to other professionals.

In the AO classification, in spite of considering the fibular fracture trait in a manner similar to that of Danis-Weber, the presence of fractures of the posterior malleolus or the presence of comminution of the fracture site may require more attention from the examiner and greater experience in the treatment of these fractures. In the present study, a moderate agreement was observed among examiners in general, regardless of the professional's experience. It is worth noting that isolated medial or posterior malleolus fracture were not representative in this classification when used by residents. This demonstrates that professional experience may influence the application of the AO classification in ankle fractures.

The data from the present study point to a wider agreement among the residents in the three classifications; it can be inferred that the knowledge passed on by this institution follows a homogeneous line of thought.

The mean level of agreement among specialists was poor; this could have occurred due to their formation in different medical institutions, and the fact that they follow diverse lines of thought and propedeutics, which are often far different from emergency care.

Regarding the general orthopedic surgeons, a moderate level of agreement (when compared with residents and specialists) was observed. In light of this finding, the authors assume that these two examiners, despite having been trained at different medical institutions, obtained a more homogeneous formation during training, or that daily practice in emergency care units requires a better and uniform communication of these classifications.

Among the classifications observed, Lauge-Hansen's presented the poorest interobserver correlation; this data has been corroborated by the studies of Tenório et al.18 and Alexandropoulos et al.3 Tenório et al.18 consider Weber's classification to be more reproducible for use in emergency services; a similar finding was observed in the present study, where a good interobserver correlation was demonstrated for this classification (a Kappa index of 0.81 when assessed among residents and of 0.93 when a resident was paired with one of the foot and ankle specialists).

Likewise, Thonsen et al.15 suggested that the Lauge-Hansen classification presents the poorest interobserver correlation, especially when he is asked to determine the stage at which the fracture is within the classification chosen by the examiner.

Several other studies have observed inconsistent interobserver agreement for classifications involving other fractures. This was demonstrated by the studies by Siebenrock and Gerber,19 who evaluated Neer's classification for proximal humeral fractures and Frandsen et al.,20 who assessed Garden's classification for femoral neck fractures. Therefore, unsatisfactory reproducibility is not a problem exclusive to ankle fracture classifications.

The present data indicates that, among the three classifications studied, the Lauge-Hansen classification presents the poorest interobserver agreement, the AO, moderate, and the Danis-Weber, an excellent interobserver agreement index.

A low familiarity with some classifications may interfere with the interpretation of radiographs, which could have influenced the results obtained in this study. In the present study, the 13 images of ankle fractures that could not be adequately classified were of isolated fractures of the medial or posterior malleolus with the use of the AO classification by the residents. Therefore, the authors believe that this type of fracture is not well represented in the AO classification, especially when considering that the difficulty in categorizing these images was observed exclusively among orthopedists with less professional experience.

Conclusion

Ankle fractures are varied and complex, and current classification schemes are limited in their ability to completely categorize certain injuries. As the understanding of ankle fractures evolves, it is clear that treatment decisions should be based less rigidly on a classification system, which should serve as a source of information for a comprehensive assessment of the fracture.

The authors concluded that there is a poor interobserver agreement of the Lauge-Hansen, Danis-Webber, and AO classifications. Among those, the one with the highest reproducibility rate is the Danis-Webber, whereas the Lauge-Hansen and AO classifications showed considerably lower reproducibilities, regardless of the professional experience of the observer.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Hospital Municipal Odilon Behrens (HMOB), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

References

- 1.Budny A.M., Young B.A. Analysis of radiographic classifications for rotational ankle fractures. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2008;25(2):139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockwood C.A., Bucholz R.W., Court-Brown C.M., Heckman J.D., Tornetta P., editors. Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandropoulos C., Tsourvakas S., Papachristos J., Tselios A., Soukouli P. Ankle fracture classification: an evaluation of three classification systems: Lauge-Hansen, A.O. and Broos-Bisschop. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauge-Hansen N. Ligamentous ankle fractures; diagnosis and treatment. Acta Chir Scand. 1949;97(6):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pimenta L.S.M. Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo; São Paulo: 1991. Estudo experimental e radiográfico das fraturas maleolares do tornozelo baseado na classificação de Lauge-Hansen. [Dissertação] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo A., Reginelli A., Zappia M., Rossi C., Fabozzi G., Cerrato M. Ankle fracture: radiographic approach according to the Lauge-Hansen classification. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013;97(Suppl 2):S155–S160. doi: 10.1007/s12306-013-0284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton W. Springer-Velarg; New York: 1984. Traumatic disorders of the ankle. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danis R. Les fractures malleolaires. In: Danis R., editor. Théorie et pratique de l’ostéosynthèse. Masson; Paris: 1949. pp. 133–165. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber B.G. 2nd ed. Verlag Hans Huber; Berne: 1972. Die Verletzungen des oberen Sprung-gelenkes. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broos P.L., Bisschop A.P. Operative treatment of ankle fractures in adults: correlation between types of fracture and final results. Injury. 1991;22(5):403–406. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(91)90106-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielson J.H., Gardner M.J., Peterson M.G., Sallis J.G., Potter H.G., Helfet D.L. Radiographic measurements do not predict syndesmotic injury in ankle fractures: an MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:216–221. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000161090.86162.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fracture and dislocation compendium. Orthopaedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(Suppl 1) v–ix, 1–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller M. In: Comprehensive classification of fractures. Bern M, editor. Muller Foundation; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig W.L., 3rd, Dirschl D.R. Effects of binary decision making on the classification of fractures of the ankle. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(4):280–283. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomsen N.O., Overgaard S., Olsen L.H., Hansen H., Nielsen S.T. Observer variation in the radiographic classification of ankle fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(4):676–678. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleiss J.L. 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1981. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis J.R., Koch G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenório R.B., Mattos C.A., Araújo L.H.C., Belangero W.D. Análise da reprodutibilidade das classificações de Lauge-Hansen e Danis-Weber para fraturas de tornozelo. Rev Bras Ortop. 2001;36(11/12):434–437. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebenrock K.A., Gerber C. The reproducibility of classification of fractures of the proximal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(12):1751–1755. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frandsen P.A., Andersen E., Madsen F., Skjødt T. Garden's classification of femoral neck fractures. An assessment of inter-observer variation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(4):588–590. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B4.3403602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]