Abstract

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of aspirin and rivaroxaban in preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE) after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods

Thirty-two patients with osteoarthritis of the knee and knee arthroplasty indication were selected. The operated patients were randomized into two groups (A and B). Group A received 300 mg of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and Group B received 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily for 14 days. Follow-up was performed weekly for four weeks and evaluated the presence of signs and symptoms of DVT, the healing of the surgical wound, and possible local complications such as hematoma, and superficial or deep infection that required surgical approach.

Results

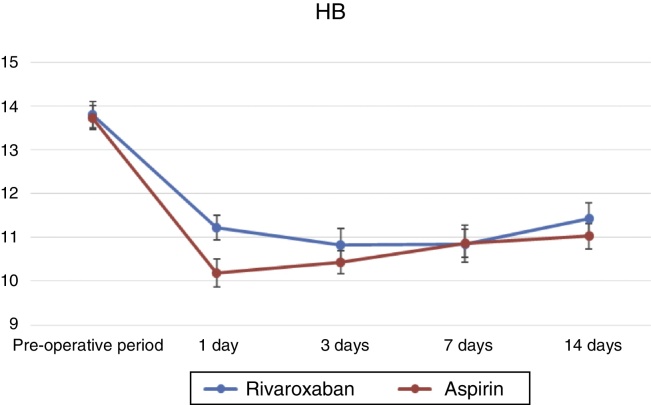

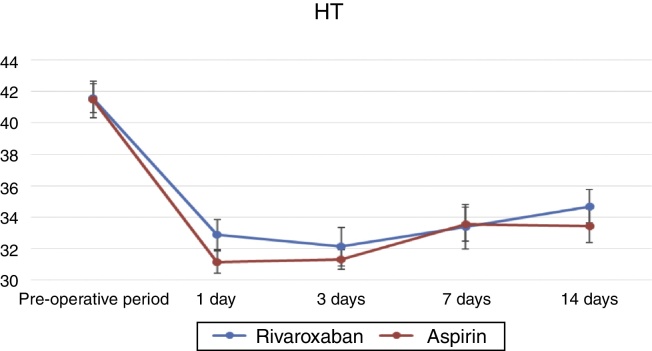

It was verified that there were no differences between groups (rivaroxaban and aspirin) regarding gender, age, and (p > 0.05). After using the general linear model (GLM) test, it was found that there was a decrease in Hb and Ht levels, preoperatively and at one, three, seven, and 14 days (Hb: p = 1.334 × 10−30; Ht: p = 1.362 × 10−28). However, they did not differ as to the type of medication (Hb: p = 0.152; Ht: p = 0.661). There were no identifiable differences in local complications, systemic complications, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), readmission to hospital, reoperation, or death (p > 0.05) between groups (rivaroxaban and aspirin).

Conclusions

Both aspirin and rivaroxaban can be considered useful among drugs available VTE the prevention after TKA.

Keywords: Knee, Arthroplasty, Osteoarthritis

Resumo

Objetivos

Comparar a eficácia e a segurança da aspirina e rivaroxabana na prevenção de tromboembolismo venoso (TEV) após a artroplastia total de joelho (ATJ).

Métodos

Foram selecionados 32 pacientes com osteoartrite do joelho e indicação de artroplastia do joelho. Os pacientes operados foram randomizados em dois grupos (A e B). Os pacientes do grupo A receberam 300 mg de ácido acetilsalicílico (aspirina) e os do grupo B receberam 10 mg de rivaroxabana diários durante 14 dias. O acompanhamento foi feito semanalmente durante quatro semanas e avaliaram-se a presença de sinais e sintomas de TVP, a cicatrização da ferida cirúrgica e possíveis complicações locais, como hematomas e infecção superficial ou profunda que necessitasse de abordagem cirúrgica.

Resultados

Foi verificado que não houve diferenças entre grupos (rivaroxabana e aspirina) quanto a gênero, idade e lateralidade (p > 0,05). Após a aplicação do teste General Linear Model (GLM), verificou-se uma queda dos níveis de Hb e Ht pré-operatórios e a um, três, sete e 14 dias (Hb: p = 1,334 × 10−30; Ht: p = 1,362 × 10−28). Entretanto, não se observaram diferenças quanto ao tipo de medicação (Hb: p = 0,152; Ht: p = 0,661). Não foram identificadas diferenças entre os grupos (rivaroxabana e aspirina) quanto a complicações locais, complicações sistêmicas, TVP, reinternação, reoperação e óbito (p > 0,05).

Conclusões

Tanto a aspirina como a rivaroxabana podem ser considerados úteis dentro das medicações disponíveis para a prevenção de TEV após ATJ.

Palavras-chave: Joelho, Artroplastia, Ostoartrose

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a very safe procedure.1 However, patients undergoing this procedure are considered to be at risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE); deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism are the most common manifestations.2 When preventive measures are not used, the incidence of DVT may reach 60% in the 90 days after surgery,3 and the incidence of fatal pulmonary embolism may reach 1.5%.4

The guidelines of the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) widely recommend the use of anticoagulants after TKA and total hip arthroplasty (THA). Although the AAOS guideline does not specifically recommend the use of aspirin, those of the ACCP strongly endorse its use (grade 1B – moderate quality evidence) as an effective agent in the prophylaxis of VTE after total arthroplasties.2

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the best pharmacological prevention; the most commonly used drugs have been enoxaparin, a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor. Nonetheless, the effective VTE prophylaxis achieved is associated with an increased incidence of local postoperative complications (hematomas, superficial and deep infection) and systemic complications (nasal, gingival, and intracranial bleeding).5, 6, 7

The use of aspirin as an effective VTE prophylaxis after TKA and THA has been widely reported, but its routine use as a medication of choice remains controversial.8 Recent studies have shown that aspirin is an effective agent in preventing VTE, with a lower risk of complications than other more aggressive anticoagulants, which can cause secretion in the surgical wound and bleeding, as well as high rates of rehospitalization, reoperation, periprosthetic infection, and even mortality.9, 10, 11 Another benefit of aspirin cited in some recent studies is its cost-effectiveness when compared with LMWHs.12 Therefore, the present study is aimed at comparing the efficacy and safety of aspirin and rivaroxaban in preventing VTE after TKA.

Methods

The study was conducted after approval by the institution's research ethics committee. All patients received and signed the informed Consent Form.

This was a prospective study. Thirty-two patients with osteoarthritis of the knee and indication of TKA for primary osteoarthrosis were selected. The exclusion criteria comprise patients allergic to one of the medications; those with coagulation disorders or liver diseases; those with history of bleeding; those in use of other anticoagulants; and those with a high or very high risk of developing thromboembolic events, such as those with obesity, very limited ambulation before surgery, a history of DVT or pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), known hypercoagulative state (such as estrogen use), and history of recent malignant neoplasia.

TKA was performed by different surgeons after a rachidian space anesthetic block, using a tourniquet. A midline approach to the knee was used with a medial parapatellar arthrotomy, a femoral cut was made using an intramedullary guide, and a tibial cut was made with an extramedullary guide; the prosthesis was secured by conventional cementation technique. After surgery, a suction drain was installed and the layers and skin were sutured prior to tourniquet removal.

After surgery, the patients were randomized into two groups through a computer-generated table (Microsoft Office Excel 2010; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, United States). Drug prophylaxis with anticoagulants was initiated 12 h after the anesthetic block. In group A, patients received 300 mg aspirin divided into two daily doses of 150 mg each; in group B, patients received a daily dose of 10 mg of rivaroxaban. In both groups, patients used the same medication until completing 14 days of use, counted from the first dose.

All patients followed the same postoperative rehabilitation protocol. On the first postoperative day, patients were stimulated and instructed to make active ankle and knee movements. On the second day, after removal of the suction drain, patients were instructed to walk with the aid of a walker; cases without clinical or surgery-related complications were discharged on the third day.

Patients were monitored periodically for the presence of complications due to the use of anticoagulants and/or signs and symptoms of thromboembolic events.

Routine laboratory tests were performed one, three, seven, and 14 days after surgery. The hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (Ht) values were recorded. The suction drain output volume was recorded at 24 and 48 h after surgery, when it was removed. In both groups, blood loss was calculated based on the Gross formula, as recommended by Sehat et al.13 and Nadler et al.14

All patients were followed-up weekly after hospital discharge; during four weeks the presence of signs and symptoms of DVT, surgical wound healing, and possible local complications, such as bruising and superficial or deep infection that would require surgical treatment were evaluated. Therefore, any evidence of secretion, hyperemia, or cellulite around the surgical wound identified by the medical team was considered a complication of wound healing.

Patients with clinical suspicion of DVT underwent Doppler ultrasonography for diagnostic confirmation and appropriate treatment if the presence of deep vein thrombi was confirmed.

All the analyzed parameters were submitted to statistical analysis in order to assess the safety of each drug in relation to the prevention of thromboembolic events, as well as the risks of complications related to its use.

Results

The selected sample consisted of 32 patients: five males (15.62%) and 27 females (84.37%). Patients were divided into two groups: group A used aspirin and group B, rivaroxaban. Group A consisted of one man (7.1%) and 13 women (92.9%), while group B consisted of four men (22.2%) and 14 women (77.8%). The mean age of patients in group A was 71.21 ± 6.35 years, vs. 67.11 ± 7.65 years in group B. Regarding laterality, group A was composed of six right knees (42.9%) and eight left (57.1%), while group B included eight left (44.4%) and ten right knees (55.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution according to gender and laterality.

| Rivaroxaban group (n = 18) | Aspirin group (n = 14) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male = 4 (22.2%) | Male = 1 (7.1%) | 0.355 |

| Female = 14 (77.8%) | Female = 13 (92.9%) | ||

| Side | Left = 10 (55.6%) | Left = 6 (42.9%) | 0.722 |

| Right = 8 (44.4%) | Right = 8 (57.1%) | ||

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 67.11 ± 7.65 | 71.21 ± 6.35 | 0.148 |

n, sample size; SD, standard deviation.

No differences were observed between groups (aspirin and rivaroxaban) regarding gender, age, and laterality; Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables (gender and laterality), and the Mann–Whitney's test, for continuous variables (age). The groups were not statistically different for these variables (p > 0.05).

Group A presented one case of deep infection (7.1%) and one case of dehiscence (7.1%); no complications were observed in 12 cases (85.8%). Group B presented one case of deep infection (5.5%) and three of dehiscence (16.7%); no systemic complications were observed in 14 cases (77.8%). In group A, one case of systemic complication was observed (7.1%). Group B did not present cases of systemic complications (Table 2). One case of DVT was observed in group A (7.1%) and two cases in group B (11%). In group A, two cases of rehospitalization and one of reoperation were observed (14.3% and 7.1%, respectively), vs. two cases of rehospitalization and two cases of reoperation (11.1% and 11.1%, respectively) in group B. As shown in Table 2, only one death was observed, in group B (5.6%).

Table 2.

Postoperative complications.

| Rivaroxaban group (n = 18) | Aspirin group (n = 14) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local complications | No = 14 (77.8%) | No = 12 (85.8%) | 0.803 |

| Dehiscence = 3 (16.7%) | Dehiscence = 1 (7.1%) | ||

| Deep infection = 1 (5.5%) | Deep infection = 1 (7.1%) | ||

| Systemic complications | No = 18 (100.0%) | No = 13 (92.9%) | 0.437 |

| Yes = 0 (0.0%) | Yes = 1 (7.1%) | ||

| DVT | No = 16 (88.9%) | No = 13 (92.9%) | 1.000 |

| Yes = 2 (11.1%) | Yes = 1 (7.1%) | ||

| Hospital readmission | No = 16 (88.9%) | No = 12 (85.7%) | 1.000 |

| Yes = 2 (11.1%) | Yes = 2 (14.3%) | ||

| Reoperation | No = 16 (88.9%) | No = 13 (92.9%) | 1.000 |

| Yes = 2 (11.1%) | Yes = 1 (7.1%) | ||

| Death | No = 17 (94.4%) | No = 14 (100.0%) | 1.000 |

| Yes = 1 (5.6%) | Yes = 0 (0.0%) |

n, sample size; DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

Using Fisher's exact test, no differences were identified between the groups (rivaroxaban and aspirin) regarding local complications, systemic complications, DVT, rehospitalization, reoperation, and death (p > 0.05).

The time of tourniquet use (mean ± SD) in group A was 119.00 ± 5.59 and in B, 122.72 ± 8.44. In group A, the 24-h drain output (mean ± SD) was 305.71 ± 196.10 and in B, 354.44 ± 276.72. In group A, the 48-h drain output (mean ± SD) was 124.21 ± 92.33 and in B, 104.78 ± 75.69. The preoperative HB values (mean ± SD) were 3.30 ± 1.13 in group A and 2.98 ± 1.48 in group B. The 14-day postoperative HB values (mean ± SD) were 2.71 ± 1.19 in group A and 2.38 ± 1.24 in group B. The preoperative HT values (mean ± SD) were 10.18 ± 4.48 in group A and 9.47 ± 4.75 in group B. The 14-day postoperative HT values (mean ± SD) were 8.04 ± 5.55 in group A and 6.89 ± 3.55 in group B. Using the Mann–Whitney test, no statistical difference was observed between the two groups for these variables (p > 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Perioperative results.

| Rivaroxaban group (n = 18) | Aspirin group (n = 14) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourniquet time (mean ± DP) | 122.72 ± 8.44 | 119.00 ± 5.59 | 0.371 |

| 24-h drain output (mean ± SD) | 354.44 ± 276.72 | 305.71 ± 196.10 | 0.834 |

| 48-h drain output (mean ± SD) | 104.78 ± 75.69 | 124.21 ± 92.33 | 0.985 |

| HB pre (mean ± SD) | −2.98 ± 1.48 | −3.30 ± 1.13 | 0.732 |

| HT pre (mean ± SD) | −9.47 ± 4.75 | −10.18 ± 4.48 | 0.790 |

| HB post-14 days (mean ± SD) | −2.38 ± 1.24 | −2.71 ± 1.19 | 0.717 |

| HT post-14 days (mean ± SD) | −6.89 ± 3.55 | −8.04 ± 5.55 | 0.372 |

n, sample size; SD, standard deviation; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; HB, hemoglobin; HT, hematocrit.

After the general linear model (GLM) test for repeated measures was used, a decrease in the post-operative levels of HB and HT at one, three, seven, and 14 days was observed (HB: p = 1.334 × 10−30; HT: p = 1.362 × 10−28). However, this value did not differ regarding the type of medication (HB: p = 0.152; HT: p = 0.661; Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of alterations in hemoglobin level (HB).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of alterations in hematocrit level (HT).

Discussion

The concern of the orthopedic community with cases of VTE after orthopedic procedures is paramount.15 If preventive measures are not adopted, the incidence of DVT can reach 60% and that of fatal pulmonary embolism, up to 1.5% within 90 days after TKA.3, 4 Currently, there is no consensus on the best strategy for VTE prophylaxis after knee and hip arthroplasty.15 This study aimed to compare aspirin and rivaroxaban in the prevention of VTE and in the incidence of post-TKA complications.

In the present study, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups regarding the incidence of VTE (p = 1.000), similarly to the recent meta-analysis by Drescher et al.,16 which evaluated only randomized studies comparing aspirin with one or more anticoagulants, and concluded that aspirin efficacy is similar to that of other anticoagulants regarding bleeding control and VTE incidence.

Some studies have reported that aspirin is effective in preventing VTE and has a lower risk of complications when compared with other more aggressive anticoagulants.15 Vulcano et al.,17 in a study with 1947 patients undergoing TKA and THA, compared the use of aspirin in relation to warfarin for the incidence of VTE and bleeding; those authors observed rates of 1.2% and 0.3%, respectively, with aspirin use, and 1.4% and 1.6% with warfarin use (n = 1947).

Therefore, the increased incidence of local or systemic bleeding is another concern in the use anticoagulants, and some studies have shown a possible lower risk of bleeding with aspirin.16 In the present series of 32 patients, no complications related to systemic bleeding were observed, and the evaluation of local bleeding through HB, HT, and postoperative drainage output control showed no statistically significant differences between groups A and B (p = 0.717; p = 0.372, and p = 0.985, respectively; Table 3).

Several studies have concluded that the use of rivaroxaban when compared with other anticoagulants increases the risk of complications related to wound healing.6, 7, 18 However, in the present study, a greater number of patients with local complications was observed in the group that used rivaroxaban (n = 3) when compared with the aspirin group (n = 1), but no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups (p = 0.803).

Alterations related to healing and increased bleeding may progress to deep infection. In the present study, two patients (one in each group) presented dehiscence of the surgical wound that evolved to deep infection with need of rehospitalization and surgical intervention for cleansing, debridement, and polyethylene exchange. However, one patient from group B (rivaroxaban) persisted with signs of infection, requiring a second surgery for prosthesis removal and spacer placement; this patient evolved to septicemia and death.

Aspirin is already considered to be an effective drug in the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebral ischemic diseases.18 The 2008 ACCP (American College of Chest Physicians) guideline recommends the use of this drug after total arthroplasties. However, although recommendation for aspirin use in the 2012 guideline is low (Grade 2C), several studies have shown that, when used in patients considered to be of low risk for VTE, it may be effective and safe after total arthroplasties.18, 19 Therefore, the similar incidence of local and systemic complications between aspirin and rivaroxaban found in the present series of patients may contribute to the consensus that aspirin is a safe drug for use in VTE prophylaxis in patients undergoing TKA.

The limitations of this prospective and randomized study include the limited number of patients, as the insufficient sample size probably influenced the degree of statistical significance with values of p > 0.05. The follow-up time of less than 30 days postoperatively may be considered too brief, considering that VTE can be observed in up to 90 days postoperatively if no antithrombotic therapy is used.3, 4 Therefore, some studies that evaluate the methods of antithrombotic prophylaxis after TKA follow the patients for at least 90 days, which is a limiting factor in the comparison of results.

Conclusion

Both aspirin and rivaroxaban can be considered useful medications among the drugs available for the prevention of VTE after TKA.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Hospital Mario Covas, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Zhan C., Kaczmarek R., Loyo-Berrios N., Sangl J., Bright R.A. Incidence and short-term outcomes of primary and revision hip replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):526–533. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falck-Ytter Y., Francis C.W., Johanson N.A., Curley C., Dahl O.E., Schulman S. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed., American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S–325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinlan D.J., Eikelboom J.W., Dahl O.E., Eriksson B.I., Sidhu P.S., Hirsh J. Association between asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by venography and symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing elective hip or knee surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(7):1438–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howie C., Hughes H., Watts A.C. Venous thromboembolism associated with hip and knee replacement over a ten-year period: a population-based study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1675–1680. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B12.16298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnett R.S., Clohisy J.C., Wright R.W., McDonald D.J., Shively R.A., Givens S.A. Failure of the American College of Chest Physicians-1A protocol for lovenox in clinical outcomes for thromboembolic prophylaxis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(3):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jameson S.S., Rymaszewska M., Hui A.C., James P., Serrano-Pedraza I., Muller S.D. Wound complications following rivaroxaban administration: a multicenter comparison with low-molecular-weight heparins for thromboprophylaxis in lower limb arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(17):1554–1558. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez-Outes A., Terleira-Fernández A.I., Suárez-Gea M.L., Vargas-Castrillón E. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total hip or knee replacement: systematic review, meta-analysis, and indirect treatment comparisons. BMJ. 2012;344:e3675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozic K.J., Vail T.P., Pekow P.S., Maselli J.H., Lindenauer P.K., Auerbach A.D. Does aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parvizi J., Ghanem E., Joshi A., Sharkey P.F., Hozack W.J., Rothman R.H. Does excessive anticoagulation predispose to periprosthetic infection? J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs R.A., Smith J.H., Kuney M., Paxton L. Does anticoagulation do more harm than good?: A comparison of patients treated without prophylaxis and patients treated with low-dose warfarin after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotke P.A., Lonner J.H. The benefit of aspirin chemoprophylaxis for thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:175–180. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238822.78895.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schousboe J.T., Brown G.A. Cost-effectiveness of low-molecular-weight heparin compared with aspirin for prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1256–1264. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sehat K.R., Evans R.L., Newman J.H. Hidden blood loss following hip and knee arthroplasty. Correct management of blood loss should take hidden loss into account. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(4):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadler S.B., Hidalgo J.H., Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery. 1962;51(2):224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalury D., Lonner J., Parvizi J. Prevention of venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty: aspirin is enough for most patients. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44(2):59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drescher F.S., Sirovich B.E., Lee A., Morrison D.H., Chiang W.H., Larson R.J. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579–585. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vulcano E., Gesell M., Esposito A., Ma Y., Memtsoudis S.G., Gonzalez Della Valle A. Aspirin for elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a multimodal thromboprophylaxis protocol. Int Orthop. 2012;36(10):1995–2002. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1588-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou Y., Tian S., Wang Y., Sun K. Administering aspirin, rivaroxaban and low-molecular-weight heparin to prevent deep venous thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(7):660–664. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butt A.J., McCarthy T., Kelly I.P., Glynn T., McCoy G. Sciatic nerve palsy secondary to postoperative haematoma in primary total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(11):1465–1467. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B11.16736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]