Abstract

Objective

To assess the tendon reconstruction technique for total rupture of the pectoralis major muscle using an adjustable cortical button.

Methods

Prospective study of 27 male patients with a mean age of 29.9 (SD = 5.3 years) and follow-up of 2.3 years. The procedure consisted of autologous grafts taken from the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons and an adjustable cortical button. Patients were evaluated functionally by the Bak criteria.

Results

The surgical treatment of pectoralis major muscle tendon reconstruction was performed in the early stages (three weeks) in six patients (22.2%) and in 21 patients (77.8%), in the late stages. Patients operated with the adjustable cortical button technique obtained 96.3% excellent or good results, with only 3.7% having poor results (Bak criteria). Of the total, 85.2% were injured while performing bench press exercises and 14.8%, during the practice of Brazilian jiu-jitsu or wrestling. All weight-lifting athletes had history of anabolic steroid use.

Conclusion

The early or delayed reconstruction of ruptured pectoralis major muscle tendons with considerable muscle retraction, using an adjustable cortical button and autologous knee flexor grafts, showed a high rate of good results.

Keywords: Anabolic agents/administration & dosage, Athletic injuries, Pectoralis muscles, Rupture, Prospective studies

Resumo

Objetivo

Avaliar a técnica de reconstrução do tendão do músculo peitoral maior com ruptura total com o uso do botão cortical ajustável.

Métodos

Estudo prospectivo de 27 pacientes do sexo masculino com média de 29,9 anos (DP = 5,3 anos) e acompanhamento de 2,3 anos. A técnica cirúrgica usada representa o uso de enxerto autólogo do tendão semitendineo e grácil e botão cortical ajustável. Os pacientes foram avaliados funcionalmente pelo critério de Bak.

Resultados

O tratamento cirúrgico de reconstrução do tendão do músculo peitoral maior foi feito na fase precoce (três semanas) em seis pacientes (22,2%) e na fase tardia em 21 (77,8%). Os pacientes operados com a técnica de botão cortical ajustável obtiveram 96,3% de excelentes ou bons resultados contra apenas 3,7% de resultados ruins (critério de Bak). Do total, 85,2% sofreram lesão no exercício do supino e 14,8% eram praticantes de jiu-jitsu ou luta. Todos os atletas de levantamento de peso tinham história de uso de esteroide anabolizante.

Conclusão

A reconstrução do tendão do músculo peitoral maior rompido, com grande retração muscular (tardia ou precoce) com o uso do botão cortical com ajuste e enxerto autólogo de flexores do joelho representa uma boa opção de tratamento.

Palavras-chave: Anabolizantes/administração & dosagem, Traumatismos em atletas, Músculos peitorais, Ruptura, Estudos prospectivos

Introduction

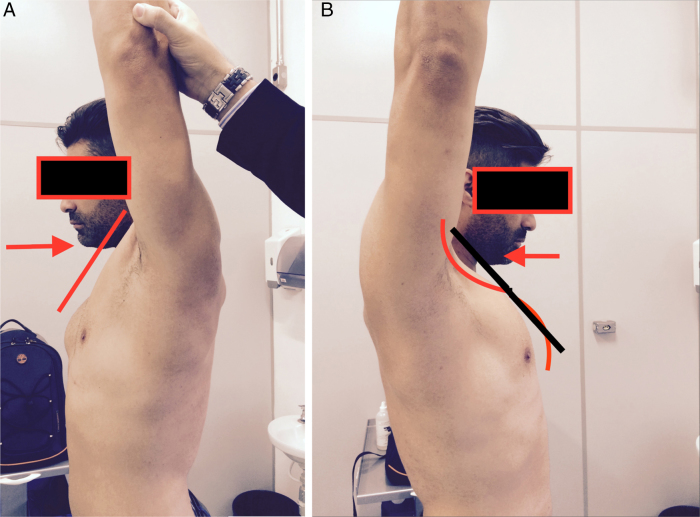

Pectoralis major muscle (PMM) tendon injuries and their treatment have been addressed in several Brazilian1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and international10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 publications over the last 20 years. The loss of strength (mainly of adduction of the humerus) and the esthetic sequelae have led several patients to seek surgical treatment for acute or chronic conditions.1, 3, 5, 24 The ready identification of the tears leading to medial PMM retraction, especially of its sternocostal portion,3, 24 can have a significant positive functional or esthetic impact. Most of the acute injuries can be treated by repairing the tear near the humerus. Some acute injuries, especially in weight-lifting athletes and in chronic users of anabolic steroids, present a complex muscular tear with greater retraction, and the efficient repair of such injuries is difficult. In these cases, reconstruction of the PMM tendon is indicated. PMM tendon injuries are defined by Shepsis et al.24 as chronic after three weeks; however, in the authors’ experience, especially after three months, in athletes and practitioners of upper limb physical activity, the PMM requires reconstruction with the use of flexor tendons2, 3, 5, 23 or other types of graft, such as calcaneal tendon allograft.26 Chronic cases present significant muscular retraction and characteristic clinical signs, such as the S sign (Fig. 1A and B).5 Some acute cases, especially in weight-lifting athletes using anabolic steroids, have complex PMM tears with significant acute retraction.3 In these patients with large PMM hypertrophy, it is very important to consider the possibility of using a graft for PMM reinsertion. This study is aimed at presenting the evolution of a surgical technique used in the last 18 years for treatment of this injury and to review the specific literature.

Fig. 1.

(A) Patient showing the normal contralateral side of a PMM injury; (B) patient with chronic PMM tear presenting the S sign.

Material and methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of this institution under CEP No. 1.527/11; all patients signed the informed consent form.

This prospective study included 27 patients, all males, mean age of 29.9 years (SD = 5.3 years), surgically treated for PMM injury and followed-up at this institution since 2006, with a mean follow-up of 2.3 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Operated patients as to age, sport, type of injury, surgical technique, postoperative clinical course, and anabolic steroid use.

| Patient | Age | Sport | Injury | Surgical technique | Bak criteria | Anabolic steroid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 27 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 2. | 27 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 3. | 30 | Brazilian jiu-jitsu | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | No |

| 4. | 37 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 5. | 26 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 6. | 33 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg- EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 7. | 35 | Brazilian jiu-jitsu | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | No |

| 8. | 24 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 9. | 30 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 10. | 29 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 11. | 37 | Brazilian jiu-jitsu | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | No |

| 12. | 32 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 13. | 31 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Poor | Yes |

| 14. | 28 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 15. | 32 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 16. | 35 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 17. | 21 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 18. | 35 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 19. | 41 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 20. | 22 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 21. | 25 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 22. | 33 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 23. | 26 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 24. | 37 | Brazilian jiu-jitsu | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Excellent | Yes |

| 25. | 26 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 26. | 22 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

| 27. | 26 | Bench press | Disinsertion | Stg-EA | Good | Yes |

Stg-EA, semitendinosus and gracilis with adjustable cortical button.

The technique used has been described in a previous study; the difference is the adjustment of tension applied on the cortical button after fixation to the humeral cortex.2, 3, 5

The patient is placed in a beach chair position, with a slope of approximately 45 degrees in order to facilitate the removal of the semitendinosus graft. The semitendinosus and gracilis grafts are removed in the conventional manner. The grafts are prepared on the surgical table by removing only the muscular part, without suturing the ends. The sutures are made after passing the graft through the pectoralis major muscle.

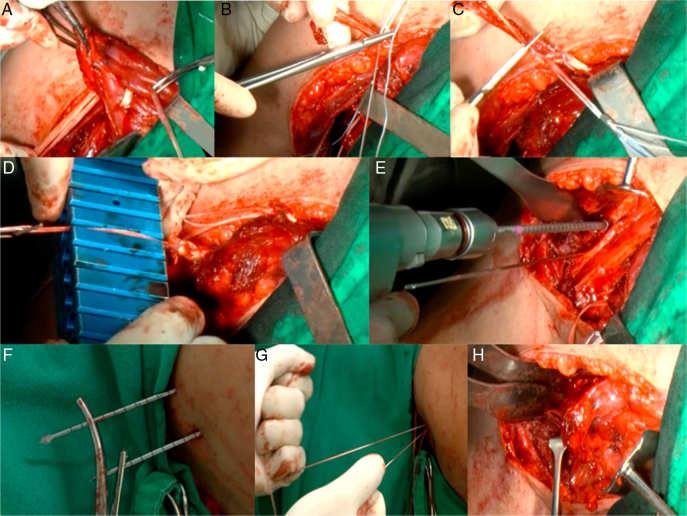

The shoulder incision is then made through an axillary route, and the muscle is sought for subcutaneously. Dissection of the deep layers of the axillary or medial regions must be avoided. After identification of the medially retracted stump, it is necessary to release the PMM from adjacent tissues and local fibrosis, using a finger or a rhomboid instrument, to achieve mobility of the injured muscle tissue. Now the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons are passed through the muscle, more or less 3 cm from the lateral border of the torn muscle.2, 3, 5 After the U-shaped progress of the tendons (grafts; Fig. 2A), non-absorbable sutures are placed at the vertices of the U in the anterior and posterior part of the muscle, in order to prevent graft slipping. After simple suturing of the vertices, a Krackov suture (Fig. 2B) is made at approximately 2 cm from the exit of the graft from the muscle, passing through the adjustable button loop (ACL TightRope®Arthrex) at the proximal and distal ends of the graft (Fig. 2C). At this point, it is important to measure the thickness of the tendons (grafts) to guide the drilling into the first cortex of the humerus (Fig. 2D). The second cortex is drilled to the cortical button diameter. In the present study, this model of button was used in all cases, but the goal is that this technique can be performed with any type of adjustable button whose tensile strength has been proven by the manufacturer.

Fig. 2.

(A) The semitendinosus and gracilis grafts are passed through the PMM, leaving the graft stumps at the posterior face of the muscle, which will be in contact with the humeral cortex, and the graft loop passing through the pectoral muscle on its anterior face; (B) Krackow sutures from one end of the graft with non-absorbable sutures passing through the adjustable cortical button loop. After passing through the muscle, 1.5 cm of graft is preserved; this part will remain inside the humeral cortex for biological integration of the reconstruction; (C) a scalpel resects the remaining graft after graft suture on the adjustable cortical button loop; (D) the graft with the suture is secured to the cortical button; its thickness is then measured for appropriate humeral cortical drilling; (E) humeral cortical drilling in the lateral region of the brachial biceps tendon in an attempt to reproduce an anatomical region below the subscapularis tendon and at least 3 cm between the proximal and distal guidewires. Now the guidewires, especially the more proximal ones, have to be placed perpendicular to the humerus to avoid, with the excessive inclination of the guidewires during their progress, that the cortical buttons exit too proximally in the posterior part of the humerus in the region of the infraspinatus muscle, which would endanger the neurovascular structures; (F) guidewires passing through the skin in the posterior region of the arm after a small incision is made, preventing the guidewires with the non-absorbable adjustment sutures from being trapped in the skin; (G) adjustment of graft and PMM tension next to humeral cortical. Now it can be observed under direct vision through the anterior surgical access, the entry of the tendon grafts into the tunnels drilled in the humerus; (H) the pectoralis muscle is drawn up to the humerus after final tensioning of the cortical adjustment button.

Through the axillary route, it is possible to approach both the medially retracted muscle and the humeral region where the torn tendon would be present.2, 3 The tendon is inserted laterally into the proximal tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle; the clavicular portion descends distally and crosses perpendicularly the sternocostal portion, which is inserted more proximally. In all bench press weight-lifting athletes, this sternocostal portion is invariably ruptured.

The lateral cortical region of the humerus is then prepared, usually with the use of a Homan-type retractor and the humerus is maintained in medial rotation to better expose the lateral region of the biceps and to facilitate the progress of the cortical button guidewire.

The progress of the specific implant guidewire through the medial and lateral cortices (Fig. 2F) should always be perpendicular to the humerus; the proximal tunnel is drilled 1.5 cm below the subscapular tendon to avoid axillary nerve injury. After measuring the diameter of the graft, a tunnel of the same width is drilled in the medial cortex.

The distance of the tunnels in the proximal and distal humerus should be measured so as not to coincide after the use of a drill bit of a larger diameter in the more medial cortex. Moreover, they must not be too close to the biceps, so as not to produce significant friction on the biceps brachii tendon.

The graft can then be carefully passed through the tunnels, always perpendicular to the humerus to prevent the exit from being too proximal to the distal cortex and the skin (Fig. 2G). After the proximal and distal wires emerge, the pectoralis major muscle is tensioned and adjusted (Fig. 2H).

After tensioning, the wires are cut or removed under control of an image intensifier.

A suction drain is required in the first 24 h to avoid a large collection through the wide subcutaneous dissection.

Subcutaneous and skin sutures can then be made with intradermal stitches (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Final cosmetic appearance after intradermal suturing of the axillary route and placing of a suction drain for 24 h.

Rehabilitation can be initiated with range of motion (ROM) gain around six weeks.

The strengthening protocol was initiated at 12 weeks, and return to sports required five to six months.

The Bak et al.11 scale was used to assess the surgical results:

-

-

Excellent: asymptomatic patient with normal ROM, without loss of strength (or up to 10%), and return to pre-injury activities;

-

-

Good: noticeable functional or isokinetic loss of up to 20%, without esthetic alterations

-

-

Fair: functional impairment that limits the return to the activity prior to injury;

-

-

Poor: functional impairment that prevents the return to the activity prior to injury;

Some patients were diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and others by ultrasonography. All patients who underwent surgical treatment presented total PMM tear or total rupture of the sternocostal part.24

Results

The mean age of the patients was 29.9 years (SD = 5.3 years). Six patients (22.2%) underwent early surgical treatment (less than three weeks) according to Shepsis et al.’s criteria,24 and 21 patients (77.8%) underwent delayed surgical treatment.

All patients were male; in those who practiced weight-lifting, the history of anabolic steroid use was 100%. The bench press exercise was the mechanism of injury in 23 patients (85.2%) and Brazilian jiu-jitsu in four patients (14.8%).

Of the cases that underwent PMM tendon reconstruction surgery, 13 patients (48.1%) presented excellent results, 13 (48.1%), good, and one (3.7%), poor.

All injuries were total or considered as total (over two-thirds of the muscle) according to the criteria of Shepsis et al.24

Of the cases that underwent PMM tendon reconstruction surgery, 13 patients (48.1%) presented excellent results, 13 (48.1%) good, and one (3.7%) poor, according to the Bak scale.11

The case with poor evolution presented pain, transient paraesthesia of the axillary nerve, and referred pain on follow-up. A surgical revision was indicated, but the patient did not return for scheduling of the procedure.

Discussion

The surgical treatment of PMM tendon rupture has been extensively studied over the last 15 years, with studies addressing anatomy, imaging diagnosis, assessment, and better understanding of tendon insertion, as well as new fixation techniques with or without reconstruction of the ruptured tendon.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

Many surgical techniques have been described in the medical literature for reinsertion of fully torn PMM tendon. The surgery can be done as a repair or reconstruction, drilling tunnels in the humerus, using anchors, screws, washers, Pec-Buttons®, and cortical buttons, among others.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

However, some injuries acute or chronic, present difficulties that sometimes hinder the efficiency of surgical treatment. In very muscular patients with PMM injury, as is the case of weight-lifters, there is greater technical difficulty in distracting the deltoid muscle to create bone tunnels. Acute cases are especially suitable for the use of anchors, screws and washers, and the Pecbutton® or ACL Tightrope® (Arthrex) implants. However, in the present study, six acute cases among 67 operated patients were observed, in which the use of a flexor graft was necessary in the early stages due to the large retraction of the PMM stump and complex muscle injury, with several ruptured layers. Thus, whenever treating very muscular athletes (hypertrophied deltoid and pectoralis major muscles) who present a PMM tear, even if acute, it is important to warn the patient that if the repair is not possible, tendon reconstruction will be required; one of the legs must always be prepared in the operation room for possible harvesting of autologous semitendinosus and gracilis grafts. Some athletes suffer PMM tear in an attempt to lift very heavy loads, over 200 kg during bench press exercises. Many of these athletes have a history of anabolic steroids use and associated chronic PMM tendinopathy.3

In this study, all weight-lifting athletes who suffered PMM tendon tear on the bench press exercises had a history of anabolic steroid use.

Acute injuries may be difficult to identify just through local edema and ecchymosis in the proximal part of the arm. Chronic injuries are easier to diagnose by evaluating the extent of retraction and loss of the anterior axillary wall. In the physical examination of the patient with chronic PMM injury, the S sign is described, which may be visible at the injury site with the patient examined in profile and in maximal arm extension in relation to the contralateral side.3, 5

Chronic and retracted injuries can be treated with grafts and implants. The following grafts have been described in the literature: semitendinosus and gracilis, calcaneus tendon, and allograft.2, 3, 5, 18, 24

The classification proposed by Tietjen28 refers to the injury site: Type I, contusion; Type II, partial injury; Type III, total rupture; and (A) sternum location, (B) muscular location, (C) musculocutaneous location, and (D) humerus cortex location.

In some cases, the injury is only observed in the sternocostal part of the PMM, which acts as a complete tear due to the important loss of horizontal adduction force on isokinetic muscle strength assessment.3, 5, 9, 24

The authors believe that currently, this is the technique that is most accessible with regard to the surgical difficulties; it is also a reproducible surgical technique in delayed reconstruction of the PMM tendon. Of the patients who underwent PMM reconstruction with cortical button with adjustment, only one presented transient paresthesia of the axillary region, which disappeared after two weeks. The authors believe that care must be taken in the progress of the superior or proximal guidewire so that it remains perpendicular, preventing it from being in a caudal or distal direction, so that the exit of the wire on the opposite cortex does not enter axillary territory. As the proximal reinsertion point is below the subscapular, the axillary nerve will be protected if these principles are followed. Another common complication in these reconstruction cases is the foreign body reaction caused by the non-absorbable sutures.3, 5 The use of cadaveric allografts has not been a common practice in PMM surgery. The literature describes the use of cadaveric grafts,18 which appears to be a good option in patients who present a great demand on the knees, and in whom the harvesting of semitendinosus and gracilis grafts may not be indicated.

The heterogeneous characteristics of both early and delayed PMM injuries are among the limitations of the present study. That implants described in PMM reconstruction are still costly, limiting their use by many orthopedic surgeons.

Conclusion

Reconstruction of a total rupture of the PMM tendon with muscle retraction (delayed or early) may be a good treatment option, with the use of a cortical button with adjustment and autologous graft of the knee flexors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Centro de Traumato-Ortopedia do Esporte, Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Pochini A.C., Andreoli C.V., Ejnisman B., Maffulli N. Surgical repair of a rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;25 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202292. pii:bcr201320229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pochini A., Ejnisman B., Andreoli C.V., Cohen M. Reconstruction of the pectoralis major tendon using autologous grafting and cortical button attachment: description of the technique. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;13(5):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Castro Pochini A., Andreoli C.V., Belangero P.S., Figueiredo E.A., Terra B.B., Cohen C. Clinical considerations for the surgical treatment of pectoralis major muscle ruptures based on 60 cases: a prospective study and literature review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(1):95–102. doi: 10.1177/0363546513506556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Castro Pochini A., Ejnisman B., Andreoli C.V., Monteiro G.C., Fleury A.M., Faloppa F. Exact moment of tendon of pectoralis major muscle rupture captured on video. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(9):618–619. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pochini A.C., Ejnisman B., Andreoli C.V., Monteiro G.C., Silva A.C., Cohen M. Pectoralis major muscle rupture in athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):92–98. doi: 10.1177/0363546509347995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pochini A.C., Ferretti M., Kawakami E.F., Fernandes Ada R., Yamada A.F., Oliveira G.C. Analysis of pectoralis major tendon in weightlifting athletes using ultrasonography and elastography. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13(4):541–546. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015AO3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueiredo E.A., Terra B.B., Cohen C., Monteiro G.C., Pochini A.C., Andreoli C.V. Footprint do tendão do peitoral maior: estudo anatômico. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48(6):519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ejnisman B., Andreoli C.V., Pochini A.C., Carrera E.F., Abdalla R.J., Cohen M. Ruptura do musculo peitoral maior em atletas. Rev Bras Ortop. 2002;37(11):482–488. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleury A.M., Silva A.C., de Castro Pochini A., Ejnisman B., Lira C.A., Andrade M.S. Isokinetic muscle assessment after treatment of pectoralis major muscle rupture using surgical or non-surgical procedures. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66(2):313–320. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aarimaa V., Rantanen J., Heikkila J., Helttula I., Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(5):1256–1262. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bak K., Cameron E.A., Henderson I.J. Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s001670050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connell D.A., Potter H.G., Sherman M.F., Wickiewicz T.L. Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;210(3):785–791. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99fe43785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dvir Z. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1995. Isokinetics – muscle testing, interpretation, and clinical applications. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan T.M., Hall H. Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon in a weight lifter: repair using a barbed staple. Can J Surg. 1987;30(6):434–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ElMaraghy A.W., Devereaux M.W. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanna C.M., Glenny A.B., Stanley S.N., Caughey M.A. Pectoralis major tears: comparison of surgical and conservative treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(3):202–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart N.D., Lindsey D.P., McAdams P.R. Pectoralis major tendon rupture: a biomechanical analysis of repair techniques. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(11):1783–1787. doi: 10.1002/jor.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph T.A., Defranco M.J., Weiker G.G. Delayed repair of a pectoralis major tendon rupture with allograft: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):101–104. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J., Brookenthal K.R., Ramsey M.L., Kneeland J.B., Herzog R. MR imaging assessment of the pectoralis major myotendinous unit: an MR imaging-anatomic correlative study with surgical correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(5):1371–1375. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller M.D., Johnson D.L., Fu F.H., Thaete F.L., Blanc R.O. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle in a collegiate football player. Use of magnetic resonance imaging in early diagnosis. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(3):475–477. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohashi K., El-Khoury G.Y., Albright J.P., Tearse D.S. MRI of complete rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Skelet Radiol. 1996;25(7):625–628. doi: 10.1007/s002560050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabuck S.J., Lynch J.L., Guo X., Zhang L.Q., Edwards S.L., Nuber G.W. Biomechanical comparison of 3 methods to repair pectoralis major ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1635–1640. doi: 10.1177/0363546512449291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schachter A.K., White B.J., Namkoong S., Sherman O. Revision reconstruction of a pectoralis major tendon rupture using hamstring autograft: a case report. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(2):295–298. doi: 10.1177/0363546505278697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schepsis A.A., Grafe M.W., Jones H.P., Lemos M.J. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):9–15. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280012701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott B.W., Wallace W.A., Barton M.A. Diagnosis and assessment of pectoralis major rupture by dynamometry. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1992;74(1):111–113. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherman S.L., Lin E.C., Verma N.N., Mather R.C. Biomechanical analysis of the pectoralis major tendon and comparison of techniques for tendo-osseous repair. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1887–1894. doi: 10.1177/0363546512452849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverstein J.A., Goldberg B., Wolin P. Proximal humerus shaft fracture after pectoralis major tendon rupture repair. Orthopedics. 2011;34(6):222. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110427-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tietjen R. Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. J Trauma. 1980;20(3):262–264. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198003000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchiyama Y., Miyazaki S., Tamaki T., Shimpuku E., Handa A., Omi H. Clinical results of a surgical technique using endobuttons for complete tendon tear of pectoralis major muscle: report of five cases. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2011;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheat H., Bugg B., Lemay K., Reed J. Tears of pectoralis major in steer wrestlers: a novel repair technique using the EndoButton. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23(1):80–82. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318272ca52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]