Abstract

Purpose

To describe the psychometric evaluation and item response theory calibration of the PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction item banks, child-report and parent-proxy editions.

Methods

A pool of 55 life satisfaction items was administered to 1,992 children 8–17 years old and 964 parents of children 5–17 years old. Analyses included descriptive statistics, reliability, factor analysis, differential item functioning, and assessment of construct validity. Thirteen items were deleted because of poor psychometric performance. An 8-item short form was administered to a national sample of 996 children 8–17 years old, and 1,294 parents of children 5–17 years old. The combined sample (2,988 children and 2,258 parents) was used in item response theory (IRT) calibration analyses.

Results

The final item banks were unidimensional, the items were locally independent, and the items were free from impactful differential item functioning. The 8-item and 4-item short form scales showed excellent reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Life satisfaction decreased with declining socio-economic status, presence of a special health care need, and increasing age for girls, but not boys. After IRT calibration, we found that 4 and 8 item short forms had a high degree of precision (reliability) across a wide range (>4 SD units) of the latent variable.

Conclusions

The PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction item banks and their short forms provide efficient, precise, and valid assessments of life satisfaction in children and youth.

Keywords: life satisfaction, evaluative well-being, subjective well-being, PROMIS, child

Introduction

Life satisfaction comprises an individual’s evaluations of their life in general and across specific contexts, such as self, family, friends, living conditions, school, and work [1,2]. These judgments result from comparisons of current versus past life, comparisons with the lives of others, and presence of such resources as positive relationships with peers and family members [3–5]. Life satisfaction is part of the multi-dimensional concept of subjective well-being, defined as “how people experience and evaluate their lives” and inclusive of experiential (positive and negative affective states), evaluative (cognitive judgments of how satisfying life is), and eudaimonic (appraisals of life as having meaning, purpose and hope) dimensions [6].

Prior research indicates that life satisfaction is lower for children with mental health problems [7–10] and substance use [11,12], higher for children with good academic performance [13], and lower for children with low family income [14]. Regarding health, life satisfaction increases with physical activity [15] and is associated with youths’ ratings of their overall health [16,17]. There has been little attention given to how illness and health services influence children’s evaluations of their lives. In one study that obtained assessments of life satisfaction and biological function, investigators found that among patients with cystic fibrosis, life satisfaction decreased between adolescence and adulthood and was positively associated with lung function [9].

Children’s life satisfaction measures can be organized into assessments of life satisfaction that are context-free (global life satisfaction), context-specific assessments of life satisfaction that yield a single score (general life satisfaction), and multi-dimensional profiles that produce scores for each context evaluated. Global unidimensional scales have been most commonly used; examples include the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale [18,19], the child modification of the Satisfaction with Life Scale [5,20], and the Cantril Ladder of well-being [21]. Contexts that are evaluated in general and multi-dimensional scales include family, friends, self, living conditions, and school [22–25].

Extant life satisfaction measures (for a comprehensive review see [26]) have limitations that call into question their content validity. Their development was not informed by children’s perspectives on how they evaluate their lives. Cognitive testing was not done to ensure item comprehensibility. Translatability reviews were not done to ensure cultural appropriateness of item-level concepts. Furthermore, item response theory was not used to develop extant measures, and it is unclear how precise the measures are across the full range of the life satisfaction continuum.

To address these limitations in extant measure development and to provide a new measure of pediatric life satisfaction that can be readily integrated into clinical research and practice applications, we used the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) mixed qualitative-quantitative approach for person-reported outcome development [27] to create item banks that result from extensive content validation of an item pool. The item pool development and its comprehensive content validation have been previously described [28]. The life satisfaction measure is part of a trio of PROMIS Pediatric measures developed to comprehensively assess subjective well-being, including positive affect (experienced well-being) [29], life satisfaction (evaluative well-being and described herein), and meaning and purpose (eudaimonic well-being and forthcoming). PROMIS is a US National Institutes of Health initiative that addressed the need for efficient (short), precise (reliable across a wide range of the latent variable), and valid measures of self-reported health that can be used in clinical research and practice [30]. PROMIS instruments assess the lived experiences of physical, mental, and social health, and are applicable across the life course.

In this manuscript, we describe the psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS Pediatric life satisfaction item pool and its calibration using item response theory. Our objectives were to produce child and parent-proxy item banks that reflect children’s perspectives on how they evaluate their lives, are well understood by children as young as age 8 years-old, are unidimensional, are free from differential item functioning by age, gender, race, and ethnicity, and measure life satisfaction with as much precision as possible across the full range of the latent variable.

Methods

Two studies were done to develop and evaluate the life satisfaction item bank. Conducted April 2011 to March 2012, Study 1 administered the full 55-item life satisfaction item pool [28] and assessed descriptive statistics, scale dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity. These data were used to identify items for deletion and to ensure that the final item pool was unidimensional and that individual items were locally independent and had monotonically increasing thresholds (i.e., that the item pool met the assumption for item response theory (IRT) modeling). Study 2 (June 2014 to September 2014) obtained a national sample that was used to further evaluate the validity of the item pool and to conduct item calibration using IRT. The Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) approved both protocols (IRB #10-007684 and IRB #13-010404). Parents gave informed consent, and children provided assent for the study.

Study 1 Data Collection

Study 1 enrolled 1,992 children aged 8–17 years and 964 parents of children aged 5–17 years. About half [53% of children (n=1,049) and 53% (n = 514) of parents] were recruited from a convenience Internet panel. Others were recruited from schools [40% of children (n=790), 30% of parents (n=293)] or the CHOP clinics [8% of children (n=153), 16% of parents (n=157)]. The child samples sizes from the clinics were: primary care (n=79), emergency department (n=42), gastroenterology (n=16), rheumatology (n=9), healthy weight (n=4), and the dialysis center (n=3). A sample of children (n=101) and parents (n=632) from the Internet panel completed the items twice 3 weeks apart (survey interval mean and median=23 days, SD=3 days, range=16–31 days) to evaluate test-retest reliability.

The Study 1 Internet sample was recruited through the Op4G.com online research panel, a community with 250,000 members who participated in research activities on their home computers. Adult participants with children aged 5–17 years were notified of their eligibility. Parents who provided consent were emailed a link to the questionnaire. After completing their assessment, parents asked their child to complete the questionnaire. The online research panel firm did not retain the number of parents invited to participate; this precluded calculation of participation rate. Parents were sent automated reminder emails every 3 days until they/their child completed the questionnaire(s) or a maximum of 3 email reminders were sent.

School-based data collection took place in 3 school districts in the states of New Hampshire, Vermont, and Texas. Fifteen schools were selected to diversify the sample’s race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and geography. Students in grades 3–12 (approximate age range 8–17 years-old), for whom parental consent could be obtained in English, except those in self-contained special education classrooms, were invited to participate. Parental consent forms were sent home at the beginning of the school year and returned to the school. Children in 5th–12th grade (age range 10–17 years-old) with parental consent completed self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaires, and staff members from the the study team read questions to groups of children in 3rd–4th grade (age range 8–9 years-old), either in their classrooms or in cafeterias. After completing the questionnaire, children were given a parent questionnaire in an envelope and instructed to take it home. Parents returned the questionnaire by mail to the study team.

For clinic-based surveys, parents and children who met study inclusion criteria (child age, English speaking, and capacity to self-report) were approached by study staff in the reception areas and were provided information about the study. If interested, parents provided consent, and then responded to the questionnaire, while they waited in the reception area, at the same time their children completed a questionnaire on tablet computers.

Study 2 Data Collection

We recruited a sample of parents of children aged 5–17 years-old from GfK Knowledge Panel, an existing dual-frame (random-digit dial and address-based) online probability panel [31,32]. Weights were used to render the study population a national sample of the US population. The initial weights adjusted for oversampling of individuals living in minority communities and Spanish-language dominant areas and other sources of error (e.g., non-response). The weights were iteratively adjusted until the sample ‘s distributions of age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, census region, metropolitan area, household internet access, and language (English/Spanish) matched those in the 2013 Current Population Survey [33]. We presented 1 item per screen to focus a respondent’s attention on each question.

Study 2 participants responded to the PROMIS Pediatric Short Form (SF) v1.0 – Life Satisfaction SF8a, 8 items that assess overall (i.e., global) life satisfaction. Parents who provided informed consent were emailed a link to an online questionnaire. After completing their questionnaire, parents of children aged 8–17 years were instructed to ask their children to participate. The child survey was administered as an audio-assisted computerized questionnaire. Children could stop the audio by advancing after recording their answer. Data collection continued until age-gender quotas were met for each form.

Life Satisfaction Item Pool

Development of the item pools evaluated in this study involved formative, qualitative research that included child, parent, and content expert semi-structured interviews, a systematic literature review, readability analysis, translatability review, and cognitive interviews [28]. These methods produced 55 items measuring global (context-free) life satisfaction and others that assess context-specific (i.e., self, family, friends, school, and neighborhood) evaluations. Items had a 4-week recall period. Response categories were frequency-based (1: never, 2: rarely, 3: sometimes, 4: often, 5: always). Parent-proxy versions replaced the pronoun “I” with “my child.”

Variables and Measures

Table 1 shows the variables and measures used for each of the 2 studies. All PROMIS Pediatric instruments were version 1.0 short forms. Additional information for all PROMIS measures is available at www.healthmeasures.net. To limit respondent burden, we used alternative questionnaire forms in both Study 1 and Study 2 for data collection.

Table 1.

Measures and Variables by Respondent and Study

| Measure/Variable Name | Categories/Definition [References] | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | Respondent | ||||

| Child | Parent-Proxy | Child | Parent-Proxy | ||

| Age | Age in years | X | X | X | X |

| Gender | Male; female | X | X | X | X |

| Race | White; Black/African-American; Asian/Pacific Islander; Other | X | X | X | X |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino; Non-Hispanic/Latino | X | X | X | X |

| Special healthcare need | Child has a chronic condition that is associated with a functional limitation, high use of medical services, or need for specialized care, or has an emotional/behavioral problem: yes; no [34,35] | X | X | ||

| Family Income | Annual household income: <$40,000; $40,000 or more | X | X | ||

| Parental relationship to child | Mother; father; other | X | X | X | |

| Parental age | 18–34 years; 35–44 years; 45+ years | X | X | X | |

| Parental educational attainment | High school or less; some college; college degree or higher | X | X | X | |

| PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction Item Pool | 55 items that measure global (context-free) life satisfaction and others that assess context-specific (i.e., self, family, friends, school, and neighborhood) evaluations | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction Short Form 8a | 8 item scale that assess global life satisfaction | X | X | ||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale, adapted for children | Global or overall life satisfaction (5-item scale) [5,20] | X | |||

| Cantril’s Well-Being Ladder | Overall well-being (single item) [43] | X | |||

| Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale | Global or overall life satisfaction (7 item scale) [18,19] | X | |||

| PROMIS Pediatric Positive Affect | Momentary positive or rewarding affective experiences such as pleasure, joy, elation, contentment, pride, affection, happiness, engagement, and excitement (8-item scale) [29] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Meaning and Purpose | A sense that life has purpose and there are good reasons for living (8-item scale) [28] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships | Quality of relationships with friends and other acquaintances (8-item scale) [38] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Mobility | Activities of physical mobility such as getting out of bed or a chair or running (8-item scale) [39] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Anger | Angry mood (e.g., irritability, reactivity), aggression (verbal and physical), and attitudes of hostility and cynicism (8-item scale) [40] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Anxiety | Fear, worry, and hyperarousal (e.g., nervousness) that reflect autonomic arousal and the experience of threat (8-item scale) [41] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Depressive Symptoms | Negative mood (e.g., sadness), decrease in positive affect (e.g., loss of interest), negative views of the self (e.g., worthlessness, low self-esteem), and negative social cognition (e.g., loneliness, interpersonal alienation) (8-item scale) [41] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Psychological Stress Experiences | Thoughts or feelings about self and the world in the context of environmental or internal challenges (8-item scale) [42] | X | X | ||

| PROMIS Pediatric Fatigue | Overwhelming, debilitating and sustained sense of exhaustion that decreases one’s ability to carry out daily activities, including the ability to do school work and to function at one’s usual level in family or social roles (10-item scale) [39] | X | X | ||

In Study 1, respondents required approximately 30 minutes to complete 125 items; seven different forms were used. Each form included the full 55-item life satisfaction item pool. Respondents were randomly assigned to complete either the PROMIS Pediatric Positive Affect or Meaning and Purpose item bank, and a subset of the validation measures (see Table 1).

For study 2, we used 2 forms that included PROMIS Pediatric 8-item short form versions for Life Satisfaction Psychological Stress Experiences, Physical Function-Mobility, Peer Relationships, and Fatigue. One subset of children was administered the Satisfaction with Life Scale for Children, Cantril’s Ladder and the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. Another subset was given Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale. Parent proxy respondents from Study 2 were administered the 5 PROMIS Pediatric short forms only. Respondents answered approximately 60 questions, requiring about 15 minutes to complete.

Classical Test Theory Analyses

All classical test theory analyses were done using data from Study 1. Each item’s mean, standard deviation, skewness, and percentage with scores at the ceiling (score of 5) or floor (score of 1) were computed. At the scale level, we examined the range of the IRT-based Life Satisfaction T-scores (see below for scoring details) and the percentage of individuals at the floor and ceiling of these scores. Reliability was evaluated with an IRT-based estimate of Cronbach’s alpha called marginal reliability [36], item-total correlations, and test-retest correlations (intraclass correlation coefficient). Multivariable regression analyses were done to explore the hypotheses, suggested by prior literature [37], that life satisfaction decreases with age, lower socio-economic status, and presence of a long-term health condition, and is no different by race or ethnicity.

Convergent validity (expected positive correlations) with other PROMIS measures of experienced and eudaimonic subjective well-being and the legacy measures of life satisfaction was expected to be moderate to high, while correlations with mobility and peer relationships was expected to be low to moderate. Discriminant validity was examined with measures of psychological stress, anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms, and fatigue (expected moderate to high negative correlations).

Testing Assumptions of IRT Analysis

Unidimensionality, local independence, and monotonicity are prerequisites for the graded response IRT model [44,45]. Using the full sample from Study 1, unidimensionality was examined using Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses (EFA and CFA) with the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimator and an oblique rotation using Mplus 6.1. Unidimensionality was supported in EFA if a single factor explained a large share of variance and the ratio of the 1st and 2nd eigenvalues was >4. We evaluated the CFA model fit with the comparative fit index (CFI > 0.95 for good fit), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > 0.95 for good fit), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.06 for good fit) [46]. A criterion of ≥0.60 for CFA factor loadings was used; those with lower loadings were considered for removal. If the fit indices did not support the unidimensional model, we planned to examine modification indices and the residual correlation matrix to identify sources of misfit and violations of assumptions, including local dependence. Items were considered locally dependent if the modification indices suggested that constraining a pair of item’s residual correlations to zero (i.e., local independence) significantly impaired model fit or if a residual correlation (the difference between observed item correlation and its model estimated value) was ≥ 0.20. Graphs of item mean scores conditional on the total test scale score minus the item score were examined to confirm item monotonicity. Non-monotonic items were removed.

Differential Item Functioning

Differential item functioning (DIF) refers to the possibility that two individuals with equivalent levels of life satisfaction would nevertheless answer questions about their life satisfaction differently as a function of another variable (e.g., age). Failure to account for DIF can lead to spurious conclusions about children’s life satisfaction. We used a multiple group factor analysis approach [47] to probe for DIF on the life satisfaction items across age, gender, race, ethnicity, and study sample. We made use of the fact that one can specify the parameters of the ordinal factor analytic model so that the model is equivalent to Samejima’s Graded Response Model [48,49] and tested whether cross-group equivalence constraints in the discrimination and the location parameters led to significant deterioration in fit. Our primary objective was to examine whether DIF substantively impacted conclusions by comparing the pattern and direction of cross-group differences in the mean and variance of the latent life satisfaction variable accounting for and ignoring DIF [47] and evaluating the distribution of IRT-based life satisfaction scores accounting for and ignoring DIF [50].

Item Bank Calibration

The final item pool was calibrated using Samejima’s Graded Response Model [48]. In IRT, calibration refers to estimating discrimination and threshold parameters for each item using a sample’s item responses. The discrimination statistic (also referred to as a slope and designated by a) measures the capacity of responses to the item to differentiate respondents by their level of the latent variable (i.e., life satisfaction). The IRT model produces threshold parameters (referred to as item difficulty, and designated as b), which correspond to the difficulty of endorsing the item. Thresholds indicate the point on the latent variable where a respondent is more likely than not to respond in (at least) the next category. For an item with five response options, the IRT model results in four item threshold statistics.

Ideally, one calibrates items using a representative sample from the population of interest. Although we had a sample of the general US pediatric population (Study 2), those children answered an eight-item short form (SF8a) rather than all items in the item pool. Thus, we could not calibrate the items in the bank using only the Study 2 sample. Although the children in Study 1 answered all of the items in the bank, it was not a representative sample, and by design included a much larger proportion of children with health conditions than the general population.

To address these issues, we used a multiple group IRT approach [49,51]. This allowed us to use all available data from both samples, as well as the design weights, to conduct calibration analyses. We statistically identified the latent variable’s metric by constraining the Study 2 group IRT mean and variance to 0 and 1, respectively. We freely estimated the Study 1 group’s IRT mean and variance, and we constrained each short form item’s parameters to equality across groups. We treated the items not presented in Study 2 as missing for the Study 2 group and did not introduce cross-group constraints for these items. As a result, the values for these parameters were estimated in the same metric as the short form item parameters but using only Study 1 sample data. Setting the IRT mean and variance to 0 and 1, respectively, sets the metric for the latent variable and parameters [52]. Because the Study 2 sample represents the general US population and we identified the latent variable’s metric using the Study 2 group only, the IRT parameters and scores estimated from these parameters can be interpreted relative to the general US pediatric population. We implemented these analyses in Mplus 7.2 using maximum likelihood estimation with a logit link.

Development of Fixed Length Forms

To create 4- (SF4a) and 8-item (SF8a and SF8b) fixed length forms, items were selected to provide as much precision (i.e., reliability) across as wide a range of children’s life satisfaction experiences as possible. We created a 4-item form that includes context-free items only, and two 8-item forms, which include the same items as the 4-item form and add 4 additional context-free items (SF8a) or 4 additional context-specific items (SF8b). Thus, the SF4a and SF8a provide a global life satisfaction measure, whereas the SF8b provides a general measure of life satisfaction. Full bank and short form marginal reliabilities were plotted by the IRT-based scale score to assess precision across the full range of the life satisfaction continuum.

Scoring

PROMIS measures are scored in the direction of their concept’s name, so higher life satisfaction scores indicate better life satisfaction and higher subjective well-being. After finalizing item parameters, we used Firestar v1.2.2, an R-based simulation software [52], and estimated full bank, SF8a, SF8b, and SF4a scale scores using Bayesian Expected A Posteriori (EAP) estimation [53]. EAP scoring uses an individual’s pattern of responses and the model’s parameters to estimate an individual’s score, called theta, which is set to a mean of 0 with a standard deviation of 1. The theta scores were linearly transformed to T-scores by multiplying by 10 and adding 50. A score of 50 represents the average life satisfaction level for children in the national sample used for calibration and centering of scores, and a score of 40, for example, is 1 standard deviation below the national average.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of the child and parent samples are shown in Table 2. All analyses were replicated for the parent-proxy banks, and can be found in the Appendix; descriptive statistics, reliability, validation, and IRT calibration results for the parent-proxy item bank were consistent with child self-report edition. Decisions to remove or retain items were based on results from the child self-report edition only.

Table 2.

Child and parent participants.

| Characteristic | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Children | Parents | Children | Parents | |

|

| ||||

| Sample size | 1,992 | 964 | 996 | 1,294 |

|

| ||||

| Survey location | ||||

| Home | 1,049 (53%) | 807 (84%) | 996 (100%) | 1,294 (100%) |

| Clinic | 153 (8%) | 157 (16%) | 0 | 0 |

| School | 790 (40%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Child Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 5 | 0 | 10 (1%) | 0 | 100 (8%) |

| 6 | 0 | 10 (1%) | 0 | 100 (8%) |

| 7 | 0 | 10 (1%) | 0 | 97 (8%) |

| 8 | 261 (13%) | 80 (8%) | 102 (10%) | 103 (8%) |

| 9 | 212 (11%) | 89 (9%) | 88 (9%) | 88 (7%) |

| 10 | 161 (8%) | 104 (11%) | 102 (10%) | 101 (8%) |

| 11 | 167 (8%) | 85 (9%) | 108 (10%) | 109 (8%) |

| 12 | 169 (8%) | 94 (10%) | 100 (10%) | 99 (8%) |

| 13 | 271 (14%) | 127 (13%) | 90 (9%) | 90 (7%) |

| 14 | 244 (12%) | 97 (10%) | 101 (10%) | 102 (8%) |

| 15 | 175 (9%) | 84 (9%) | 104 (10%) | 104 (8%) |

| 16 | 169 (9%) | 91 (9%) | 107 (11%) | 107 (8%) |

| 17 | 163 (8%) | 83 (9%) | 94 (9%) | 94 (7%) |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1,014 (51%) | 475 (49%) | 491 (49%) | 640 (49%) |

| Female | 975 (49%) | 488 (51%) | 505 (51%) | 654 (51%) |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 1,492 (76%) | 711 (75%) | 731 (73%) | 954 (74%) |

| African-American or Black | 221 (11%) | 129 (14%) | 96 (10%) | 126 (10%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 86 (4%) | 42 (4%) | 50 (5%) | 60 (5%) |

| Other | 154 (10%) | 62 (7%) | 119 (11%) | 154 (12%) |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 341 (16%) | 118 (13%) | 153 (15%) | 215 (17%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1,624 (84%) | 824 (87%) | 843 (85%) | 1,079 (83%) |

|

| ||||

| Special Healthcare Need | --- | --- | 270 (28%) | 328 (26%) |

|

| ||||

| Parental and Family Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Annual household income | ||||

| Less than $40,000 | --- | --- | 251 (25%) | 348 (27%) |

| $40,000 or more | 745 (75%) | 946 (73%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Relationship to child | ||||

| Mother | --- | 740 (78%) | 707 (71%) | 939 (73%) |

| Father | 146 (15%) | 234 (24%) | 293 (23%) | |

| Other | 68 (7%) | 53 (5%) | 59 (5%) | |

|

| ||||

| Parental Age (years) | ||||

| 18–34 | --- | 131 (25%) | 131 (13%) | 273 (21%) |

| 35–44 | 248 (48%) | 413 (41%) | 546 (42%) | |

| 45+ | 135 (26%) | 452 (45%) | 475 (37%) | |

|

| ||||

| Parental Educational attainment | ||||

| High school or less | --- | 112 (19%) | 172 (17%) | 227 (17%) |

| Some college | 236 (39%) | 363 (36%) | 459 (35%) | |

| College degree or higher | 251 (42%) | 461 (46%) | 608 (47%) | |

Item Deletions

Six items (life was very good, satisfied with my life situation, wanted to change things in my life, happy with my personal life, happy with my friendships, and wanted to live in a different place) were deleted because of local dependence with other items. Three (life was perfect wanted a different life, wanted a better life) were excluded because of non-monotonic thresholds. All four of the negatively worded items (life was bad, unhappy with my life, felt bad about my life, hated my life) were deleted because of low factor loadings (<0.40). These deletions left 42 items, all of which were positively worded.

Item-level Analyses

Item-level means ranged from 3.57 (life situation was excellent) to 4.23 (life was great and happy with my family life)—Table 3. Floor effects (% endorsing never, indicative of lower life satisfaction) were minimal, while ceiling effects (% endorsing always, indicative of higher life satisfaction) were more common. The range of item-total correlations was 0.54 to 0.89, and the range of item-level test-retest correlations was 0.69 to 0.85.

Table 3.

PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction, Child Self-Report Edition, item-level descriptive statistics, reliability, and factor loadings; data are from Study 1.

| Item Stem | Mean (SD) | Floor (% Never) | Ceiling (% Always) | Item-total correlation (r value) | Test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation) | CFA Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My life was ideal. | 4.03 (1.06) | 5.2 | 33.1 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| My life was the best. | 3.72 (1.23) | 6.0 | 29.6 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| My life was outstanding. | 3.87 (1.14) | 7.2 | 33.5 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.89 |

| My life was excellent. | 3.64 (1.14) | 4.2 | 36.1 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.88 |

| My life was great. | 4.23 (1.03) | 4.1 | 41.6 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| My life was good. | 4.06 (1.04) | 2.6 | 44.1 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.92 |

| My life was going very well. | 3.84 (1.17) | 2.8 | 41.2 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| My life was just right. | 3.88 (1.12) | 5.9 | 36.5 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| The conditions of my life were excellent. | 3.90 (1.05) | 5.9 | 36.8 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| My life situation was excellent. | 3.57 (1.20) | 2.9 | 34.2 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| I was happy with the way things were. | 4.08 (1.02) | 4.0 | 35.7 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| I had what I wanted in life. | 3.70 (1.17) | 5.2 | 26.3 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.80 |

| I had what I needed in life. | 3.84 (1.16) | 2.3 | 43.1 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.74 |

| I got the things I wanted in life. | 3.96 (1.14) | 3.8 | 27.8 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| My life was better than most kids’ lives. | 3.76 (1.17) | 6.8 | 26.8 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.74 |

| I enjoyed my life more than most kids enjoyed their lives. | 4.11 (1.01) | 4.9 | 30.9 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| I lived as well as other kids. | 3.94 (1.07) | 3.7 | 36.9 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.84 |

| My life was as good as most kids’ lives. | 3.72 (1.10) | 4.5 | 36.6 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.74 |

| I was satisfied with the friends I have. | 4.09 (0.99) | 2.7 | 53.3 | 0.54 | 0.84 | 0.61 |

| I was happy with my social life. | 4.01 (1.07) | 3.4 | 40.9 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| I was happy with my family life. | 4.23 (0.98) | 3.3 | 50.4 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| I was happy with my life at school. | 3.85 (1.17) | 4.9 | 36.6 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.73 |

| I was happy with my life at home. | 4.13 (1.04) | 3.2 | 46.4 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.84 |

| I was happy with my life in my neighborhood. | 3.89 (1.13) | 3.7 | 41.6 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 0.70 |

| I was happy with my life in my community. | 3.73 (1.14) | 2.7 | 36.9 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| I was satisfied with my free time. | 4.14 (1.09) | 4.5 | 44.5 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.75 |

| I was satisfied with my skills and talents. | 3.93 (1.06) | 3.1 | 45.0 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.71 |

| I was satisfied with my life. | 4.07 (1.04) | 2.6 | 43.1 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.89 |

| I felt extremely positive about my life. | 3.84 (1.18) | 4.7 | 36.4 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.90 |

| I was happy with my life. | 4.04 (1.04) | 2.4 | 46.9 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.94 |

| I felt very good about my life. | 4.05 (1.09) | 2.5 | 43.8 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.94 |

| I felt good about my life. | 4.03 (1.13) | 2.1 | 42.6 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

| I had a good life. | 4.18 (1.03) | 1.9 | 46.9 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.94 |

| I felt positive about my life. | 3.96 (1.12) | 2.5 | 41.5 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| I had fun. | 4.07 (0.99) | 1.9 | 51.4 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.88 |

| I had a lot of fun. | 4.14 (1.04) | 2.3 | 49.9 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.87 |

| I enjoyed my life. | 4.04 (1.03) | 2.4 | 49.5 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| I liked the way I lived my life. | 4.08 (1.08) | 2.5 | 41.1 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| My life was worthwhile. | 4.19 (1.01) | 2.4 | 47.9 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.81 |

| My life went well. | 4.12 (1.05) | 2.0 | 42.7 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.93 |

| I lived my life well. | 4.08 (1.02) | 2.0 | 41.8 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| I was satisfied with my life in general. | 4.17 (0.98) | 3.0 | 46.7 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

Dimensionality

The ratio of the 1st and 2nd eigenvalues from EFA using all 42 items in the item bank was 24; the first extracted factor accounted for 72% of the variance. The CFA model fit statistics supported unidimensionality (CFI 0.97, TLI 0.96, and RMSEA 0.09). The factor loadings ranged from 0.61 to 0.94 (Table 3). These findings provide strong support that responses to the 42 items measure a unidimensional factor.

IRT Analyses

The item with the best discrimination, providing the greatest level of information about life satisfaction, was felt very good about my life (Table 4). The nine context-specific items (e.g., satisfied with the friends I have) provided less discrimination than the context-free items. The range of threshold parameters was −3.51 (satisfied with the friends I have) to 0.56 (my life was better than most kids’ lives).

Table 4.

Item Response Theory Item Parameters for the 42-Item PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction Item Bank, Child Self-Report Edition, and Short Form Item Assignment.

| Item stem | Short Forms | Item Discrimination | Item Thresholds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | |||

| My life was ideal. | 3.33 | −2.07 | −1.42 | −0.64 | 0.20 | |

| My life was the best. | SF8a | 3.71 | −1.97 | −1.38 | −0.64 | 0.30 |

| My life was outstanding. | SF8a | 3.83 | −1.82 | −1.29 | −0.60 | 0.21 |

| My life was excellent. | 3.28 | −2.21 | −1.49 | −0.79 | 0.11 | |

| My life was great. | SF8a | 5.34 | −2.02 | −1.45 | −0.80 | −0.04 |

| My life was good. | 4.64 | −2.32 | −1.76 | −1.03 | −0.13 | |

| My life was going very well. | 5.44 | −2.21 | −1.54 | −0.95 | −0.06 | |

| My life was just right. | 3.35 | −2.01 | −1.49 | −0.78 | 0.11 | |

| The conditions of my life were excellent. | 4.01 | −1.94 | −1.44 | −0.75 | 0.09 | |

| My life situation was excellent. | 2.70 | −2.52 | −1.76 | −0.85 | 0.20 | |

| I was happy with the way things were. | 3.29 | −2.23 | −1.54 | −0.86 | 0.12 | |

| I had what I wanted in life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 2.52 | −2.27 | −1.49 | −0.61 | 0.45 |

| I had what I needed in life. | 2.05 | −2.92 | −2.04 | −1.12 | −0.03 | |

| I got the things I wanted in life. | 2.29 | −2.51 | −1.59 | −0.68 | 0.46 | |

| My life was better than most kids’ lives. | 1.88 | −2.30 | −1.44 | −0.50 | 0.56 | |

| I enjoyed my life more than most kids enjoyed their lives. | 2.26 | −2.35 | −1.57 | −0.66 | 0.35 | |

| I lived as well as other kids. | 2.76 | −2.39 | −1.75 | −0.92 | 0.10 | |

| My life was as good as most kids’ lives. | 1.98 | −2.56 | −1.80 | −0.92 | 0.17 | |

| I was satisfied with the friends I have. | SF8b | 1.34 | −3.51 | −2.49 | −1.60 | −0.37 |

| I was happy with my social life. | 1.85 | −2.79 | −1.96 | −1.06 | 0.06 | |

| I was happy with my family life. | SF8b | 2.97 | −2.34 | −1.68 | −1.10 | −0.28 |

| I was happy with my life at school. | 1.98 | −2.46 | −1.61 | −0.84 | 0.18 | |

| I was happy with my life at home. | 2.90 | −2.42 | −1.71 | −1.03 | −0.17 | |

| I was happy with my life in my neighborhood. | SF8b | 1.73 | −2.82 | −1.96 | −0.97 | 0.03 |

| I was happy with my life in my community. | 2.56 | −2.60 | −1.75 | −0.87 | 0.11 | |

| I was satisfied with my free time. | 2.02 | −2.50 | −1.85 | −1.06 | −0.09 | |

| I was satisfied with my skills and talents. | SF8b | 1.88 | −2.82 | −1.93 | −1.08 | −0.09 |

| I was satisfied with my life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 3.87 | −2.39 | −1.80 | −1.03 | −0.11 |

| I felt extremely positive about my life. | 3.78 | −2.07 | −1.41 | −0.72 | 0.10 | |

| I was happy with my life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 5.34 | −2.27 | −1.65 | −1.03 | −0.21 |

| I felt very good about my life. | 5.47 | −2.29 | −1.62 | −0.95 | −0.13 | |

| I felt good about my life. | 4.14 | −2.47 | −1.64 | −0.98 | −0.08 | |

| I had a good life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 4.91 | −2.48 | −1.80 | −1.11 | −0.24 |

| I felt positive about my life. | 4.10 | −2.37 | −1.65 | −0.97 | −0.05 | |

| I had fun. | 3.29 | −2.62 | −1.90 | −1.20 | −0.31 | |

| I had a lot of fun. | 2.96 | −2.60 | −1.90 | −1.17 | −0.27 | |

| I enjoyed my life. | SF8a | 4.99 | −2.33 | −1.67 | −1.07 | −0.25 |

| I liked the way I lived my life. | 3.44 | −2.44 | −1.75 | −0.98 | −0.03 | |

| My life was worthwhile. | 2.67 | −2.65 | −1.86 | −1.14 | −0.22 | |

| My life went well. | 4.88 | −2.43 | −1.75 | −1.00 | −0.10 | |

| I lived my life well. | 2.83 | −2.68 | −1.97 | −1.02 | −0.03 | |

| I was satisfied with my life in general. | 3.86 | −2.31 | −1.73 | −1.05 | −0.20 | |

Note: SF4a: 4-item life satisfaction short form; SF8a: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional global life satisfaction items; and, SF8b: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional context-specific life satisfaction items.

Short Forms

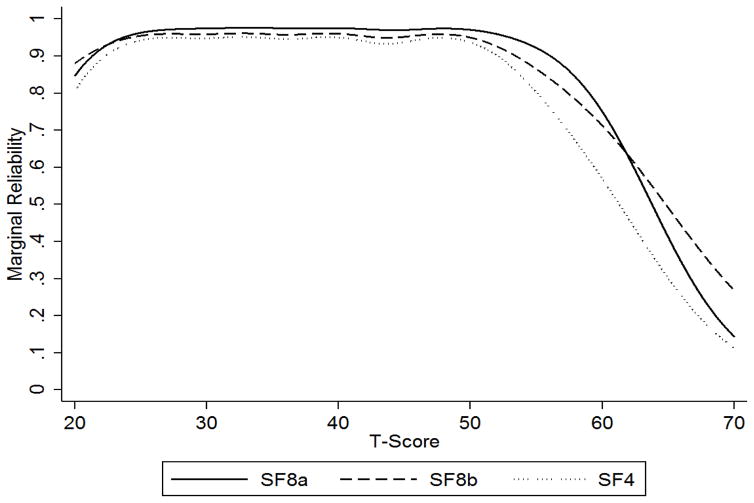

We selected items based on content and IRT item discrimination and threshold parameter estimates to constitute a single 4-item and two 8-item short forms (Table 4). For the 4-item short form, items with high levels of item discrimination were preferred, because this statistic is reflective of its ability to differentiate among individuals at different ranges of life satisfaction. The 4 items selected are each a measure of global (context-free) life satisfaction. Both 8-item short forms embedded the 4-item form. The SF8a included 4 additional items that assessed global life satisfaction, while the SF8b included 4 additional items for specific life domains, namely family, friends, self, and neighborhood. The school context was not included because children are not in school for part of the year. The marginal reliability of the three short forms (Figure 1) illustrates acceptable levels of precision across a wide range of the latent variable with 8-item forms providing more precision at high levels of life satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Marginal reliability by short form, child-report.

Scale-Level Analyses

The range in T-scores for the full item bank spanned 5.5 standard deviations (13–68), while the range for the short forms was 4.2 standard deviations for SF8a, 4.5 standard deviations for SF8b, and 3.9 standard deviations for SF4a. Fewer than 1% of individuals had a floor effect, although ceiling effects were seen among 7% (item bank), 15% (SF8a), 14% (SF8b), and 20% (4-item short form) of respondents. Marginal reliability exceeded 0.89 and test-retest reliability exceeded 0.79 for the item bank and short forms. The correlation between child-report and parent-proxy report for the SF4a was, 0.66, SF8a was 0.67, and 0.68 for the SF8b.

Validity

The item bank and short forms showed excellent concurrent validity with extant measures of life satisfaction (approximate correlations of 0.7), and they were strongly correlated with positive affect (experienced well-being) and meaning and purpose (eudaimonic well-being) (Table 5). The associations were weaker, but still positive, with peer relationships and physical functioning-mobility. Regarding discriminant validity, the largest negative correlations were observed with anger, depressive symptoms, and stress, intermediate for fatigue, and lowest for anxiety. The magnitude of the correlations was similar among the item bank and the short forms.

Table 5.

Scale-Level descriptive statistics, reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity, Child Self-Report Edition

| Item Bank, 42 Items | SF8a, Items | SF8b, 8 Items | SF4a, 4 Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Descriptive Statistics (Study 1, n=1,992) | ||||

| Range | 13.3–68.3 | 20.4–62.5 | 17.8–62.9 | 21.3–60.6 |

| Mean (SD) | 47.7 (10.3) | 47.6 (9.7) | 47.7 (9.6) | 47.6 (9.4) |

| Floor, n (%) | 2 (0.1%) | 17 (0.9%) | 8 (0.4%) | 18 (0.9%) |

| Ceiling, n (%) | 135 (6.6%) | 304 (15.3%) | 282 (14.2%) | 407 (20.4%) |

|

| ||||

| Reliability | ||||

| Marginal Reliability | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Test-Retest ICC (Study 1 Retest Sample, n=101) | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

|

| ||||

| Existing Life Satisfaction Measures, Pearson’s r | ||||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (Study 2, n=495) | - | 0.71 | - | 0.70 |

| Cantril’s Ladder (Study 2, n=504) | - | 0.67 | - | 0.64 |

| Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (Study 2, n=492) | - | 0.71 | - | 0.71 |

|

| ||||

| Convergent Validity with PROMIS Measures, Pearson’s r | ||||

| Positive Affect (Study 1, n=1,033) | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.77 |

| Meaning and Purpose (Study 1, n=1,065) | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| Peer Relationships (Study 2, n=996) | - | 0.56 | - | 0.53 |

| Physical Function-Mobility (Study 2, n=996) | - | 0.33 | - | 0.31 |

|

| ||||

| Discriminant Validity with PROMIS Measures, Pearson’s r | ||||

| Anger (Study 1, n=222) | −0.59 | −0.60 | −0.63 | −0.61 |

| Anxiety (Study 1, n=225) | −0.36 | −0.37 | −0.42 | −0.41 |

| Depressive Symptoms (Study 1, n=225) | −0.59 | −0.59 | −0.63 | −0.63 |

| Psychological Stress Experiences (Study 2, n=992) | - | −0.62 | - | −0.61 |

| Fatigue (Study 2, n=996) | - | −0.50 | - | −0.48 |

Note: SF4a: 4-item life satisfaction short form; SF8a: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional global life satisfaction items; and, SF8b: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional context-specific life satisfaction items.

We fit a multivariable regression model, which regressed life satisfaction on covariates, with an age-gender interaction term because we observed this interaction in exploratory data analysis. Results indicated a significant age by gender interaction, showing that adolescent girls (13–17 years-old) had lower life satisfaction than those 8–12 years-old, but the same age-related effect did not hold for boys (Table 6). We also observed lower life satisfaction for children from families in income of less than $40,000 per year and for children with a special health care need. We did not observe race or ethnicity differences in life satisfaction.

Table 6.

Correlates of life satisfaction from multivariable regression; data are from Study 2 and life satisfaction was measured with the SF8a.

| Covariate | Beta Coefficient (SE)1 | p-value | 95% CIs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intercept | 49.3 (0.7) | <.001 | 48.0, 50.5 |

|

| |||

| Age, years | |||

| 8–12 | 0.2 (1.8) | .900 | −3.4, 3.8 |

| 13–17 | -- | ||

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | −2.3 (0.8) | .006 | −3.9, −0.7 |

| Male | -- | ||

|

| |||

| Age*Gender Interaction | |||

| 8–12 year-old females | 2.9 | .013 | 0.6, 5.1 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | -- | ||

| African-American or Black | 1.4 (1.0) | .174 | −0.6, 3.4 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.7 (1.4) | .243 | −1.1, 4.5 |

| Other | 0.5 (0.9) | .601 | −1.3, 2.2 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.5 (0.8) | .063 | −0.1, 3.1 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | -- | ||

|

| |||

| Family Income | |||

| <$40,000 per year | −1.7 (0.7) | .014 | −3.0, −0.3 |

| $40,000 or more per year | -- | ||

|

| |||

| Special Healthcare Need | |||

| Yes | −2.9 (0.6) | <.001 | −4.2, −1.6 |

| No | -- | ||

The dashes indicate the reference group.

Special health care need was measured using the Children with Special Health Care Needs screener, which identifies children with a chronic condition (medical and behavioral health disorders) that affects daily functioning or receipt of medical care services.

Differential Item Functioning

Although we found statistically significant DIF across each of the sociodemographic variables, the differences between scores accounting for DIF and ignoring DIF (i.e., impact) were small. The mean differences for the item bank, SF-8, SF-4 were all less 0.1 SD units. Almost all the item-level differences were less than a 0.2 SD units. Scores ignoring DIF were highly correlated with scores incorporating DIF (>0.99) and the scatter plots of scores ignoring and adjusting for DIF showed a nearly perfect linear relationship with no heteroskedasticity. We found no evidence for statistically significant DIF across samples.

Discussion

The PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction item bank includes 42 items that assess the positive feelings of having a good life, also called evaluative well-being [6]. A child self-report edition can be used for children 8–17 years-old, while a parent-proxy edition with comparable psychometric properties can be used for children 5–17 years old. Development of the item pools evaluated in this study involved formative, qualitative research that included child, parent, and content expert semi-structured interviews, a systematic literature review, readability analysis, translatability review, and cognitive interviews. The initial item pool generated these methods, and previously described [28], included 55-items representing global and context-specific life satisfaction concepts. In this study we conducted item and scale level classical test and modern measurement analyses following PROMIS methodological guidelines [54]. A total of 13 items were removed because they had low factor loadings, local dependence, or non-monotonically increasing item thresholds. The final item pool demonstrated unidimensionality and local independence, important assumptions of item response theory modeling. The item pool was calibrated using the graded response model. Based on results from these analyses, 8-item and 4-item short forms were developed.

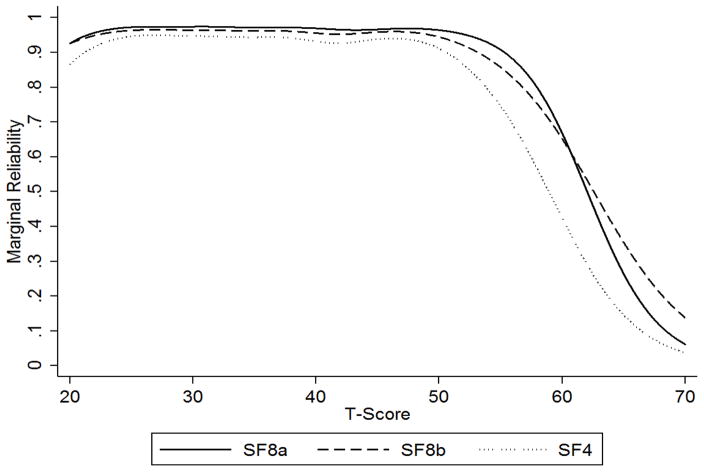

The item bank and short form scales have excellent reliability across a wide range of the latent variable, as assessed by marginal reliability, and excellent test-retest reliability. Of the 42 items in the item bank, 33 assess life satisfaction overall and 9 assess satisfaction with specific life domains (self, family, friends, living conditions, and school). The 4-item short form includes context-free items, as does the 8-item SF8a. We also constructed a second 8-item short from (SF8b), which embeds the 4-item form and items related to satisfaction with self (skills and talents), family, friends, and neighborhood. The 8-item forms have superior precision at the high end of the latent variable compared with the 4-item, less ceiling effect, and a greater measurement range. Another advantage of the SF8b is that it provides item-level information about satisfaction with self, family, friends, and neighborhood. Choice of form will therefore balance efficiency (number of items), content, and need to detect change among children with high levels of life satisfaction.

Our results provide support for the construct validity of the measures, which showed concurrent validity with extant measures of life satisfaction and positive psychological functioning, and discriminant validity with measures of emotional distress and fatigue. Similar to other studies [37], we found lower life satisfaction among children with a chronic illness and among those with low family income, while no differences were detected by race and ethnicity. The age-related decline for girls but not boys is likely due to the well known rise in emotional distress among adolescent girls [55], but this effect in declining positive psychological functioning calls out for further research to understand individual life satisfaction trajectories for girls and boys. Another limitation is that this study did not include an assessment of the associations between life satisfaction and measures of disease activity, which is an important attribute of the clinical validity of the measure, although we did find lower life satisfaction in our cross-sectional analyses for children with a special health care need. Finally, the short form ceiling effects of 15–20% indicate that these scales have limited ability to detect change for children at the highest level of life satisfaction.

Much of the data for this study was collected from two Internet panels. Study 1 used a convenience panel and Study 2 used a probability-based panel. Advantages of Internet panels include their efficiency with which large amounts of data can be collected, the accessibility of diverse populations, and standardization of the data collection process [56]. Because not all individuals and families have access to home computers and participants of Internet panels tend to have a higher socio-economic status than the general US population [57], we cannot say that the study samples were nationally representative; rather, it is fair to say that the PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction measures have been standardized to a national, highly diverse sample.

In summary, the PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction item bank provides efficient, precise, and valid short forms that can be used to assess a child’s level of evaluations of his or her life as good. The scales have excellent precision across a wide range of the latent variable, and preliminary evidence for their construct validity. The child-report edition can be used for children 8–17 years-old, and a Parent-Proxy edition is available for children ages 5–7 years-old.

Figure A1.

Marginal reliability by short form, parent-proxy report.

Table A1.

PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction, Parent-Proxy Edition, item-level descriptive statistics, reliability, and factor loadings; data are from Study 1.

| Item Stem | Mean (SD) | Floor (% Never) | Ceiling (% Always) | Item-total correlation (r value) | Test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation) | CFA Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My child’s life was ideal. | 3.83 (1.05) | 3.83 | 29.33 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| My child’s life was the best. | 3.95 (0.99) | 2.59 | 32.85 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| My child’s life was outstanding. | 3.95 (1.02) | 2.69 | 34.40 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| My child’s life was excellent. | 4.09 (0.98) | 1.97 | 41.45 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| My child’s life was great. | 4.06 (0.98) | 1.76 | 39.59 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| My child’s life was good. | 4.31 (0.82) | 0.73 | 48.50 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| My child’s life was going very well. | 4.26 (0.89) | 1.45 | 47.98 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| My child’s life was just right. | 4.04 (0.97) | 2.28 | 37.62 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| The conditions of my child’s life were excellent. | 4.04 (1.0) | 2.49 | 38.86 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| My child’s life situation was excellent. | 4.12 (0.94) | 1.66 | 41.55 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| My child was happy with the way things were. | 3.96 (1.03) | 3.73 | 34.30 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.86 |

| My child had what he/she wanted in life. | 3.89 (0.98) | 2.59 | 29.74 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.85 |

| My child had what he/she needed in life. | 4.36 (0.84) | 1.14 | 53.89 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.73 |

| My child got the things he/she wanted in life. | 3.97 (0.93) | 1.24 | 32.33 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| My child felt that his/her life was better than most kids’ lives. | 3.68 (1.11) | 5.49 | 26.32 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| My child enjoyed his/her life more than most kids enjoyed their lives. | 3.84 (1.07) | 3.73 | 31.50 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.79 |

| My child felt he/she lived as well as other kids. | 4.04 (0.98) | 2.49 | 38.13 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| My child’s life was as good as most kids’ lives. | 4.27 (0.90) | 1.45 | 50.16 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.78 |

| My child was satisfied with the friends he/she has. | 4.20 (0.94) | 1.55 | 46.84 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| My child was happy with his/her social life. | 4.10 (0.99) | 1.87 | 43.11 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| My child was happy with his/her family life. | 4.22 (0.94) | 1.55 | 48.19 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| My child was happy with his/her life at school. | 4.01 (1.02) | 2.49 | 38.03 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.80 |

| My child was happy with his/her life at home. | 4.19 (0.94) | 2.18 | 45.39 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

| My child was happy with life in his/her neighborhood. | 4.01 (1.04) | 2.69 | 40.62 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.78 |

| My child was happy with life in his/her community. | 4.07 (0.93) | 1.66 | 37.82 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| My child was satisfied with his/her free time. | 4.09 (0.95) | 1.55 | 40.10 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| My child was satisfied with his/her skills and talents. | 4.13 (0.95) | 1.97 | 41.76 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.77 |

| My child was satisfied with his/her life. | 4.22 (0.91) | 1.66 | 46.22 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.95 |

| My child felt extremely positive about his/her life. | 3.99 (1.04) | 2.59 | 38.34 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| My child was happy with his/her life. | 4.19 (0.95) | 1.87 | 45.39 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| My child felt very good about his/her life. | 4.21 (0.93) | 1.55 | 46.63 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.96 |

| My child felt good about his/her life. | 4.17 (0.93) | 1.87 | 43.21 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| My child had a good life. | 4.39 (0.78) | 0.73 | 53.89 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| My child felt positive about his/her life. | 4.18 (0.95) | 2.28 | 44.87 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| My child had fun. | 4.28 (0.88) | 1.35 | 48.81 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| My child had a lot of fun. | 4.24 (0.91) | 1.24 | 48.81 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.89 |

| My child enjoyed his/her life. | 4.24 (0.90) | 1.24 | 47.46 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.95 |

| My child liked the way he/she lived his/her life. | 4.15 (0.89) | 1.35 | 40.73 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| My child’s life was worthwhile. | 4.55 (0.73) | 0.52 | 66.32 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| My child’s life went well. | 4.30 (0.81) | 0.62 | 48.60 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.93 |

| My child felt he/she lived his/her life well. | 4.15 (0.94) | 1.55 | 42.90 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| My child was satisfied with his/her life in general. | 4.26 (0.90) | 1.45 | 48.91 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.93 |

Table A2.

Item Response Theory Item Parameters for the 42-Item PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction Item Bank, Parent-Proxy Edition, and Short Form Item Assignment.

| Item stem | Short Forms | Item Discrimination | Item Thresholds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | ||

| My child’s life was ideal. | 3.16 | −2.27 | −1.71 | −0.84 | 0.29 | |

| My child’s life was the best. | SF8a | 3.89 | −2.30 | −1.78 | −0.94 | 0.15 |

| My child’s life was outstanding. | SF8a | 3.76 | −2.32 | −1.67 | −0.88 | 0.16 |

| My child’s life was excellent. | 3.09 | −2.57 | −1.92 | −1.15 | −0.11 | |

| My child’s life was great. | SF8a | 4.69 | −2.48 | −1.80 | −1.01 | −0.05 |

| My child’s life was good. | 4.98 | −2.77 | −2.16 | −1.41 | −0.31 | |

| My child’s life was going very well. | 5.35 | −2.47 | −2.01 | −1.30 | −0.31 | |

| My child’s life was just right. | 3.23 | −2.52 | −1.97 | −1.08 | 0.00 | |

| The conditions of my child’s life were excellent. | 3.41 | −2.42 | −1.84 | −1.09 | −0.03 | |

| My child’s life situation was excellent. | 2.71 | −2.77 | −2.09 | −1.23 | −0.09 | |

| My child was happy with the way things were. | 3.66 | −2.24 | −1.80 | −1.09 | 0.09 | |

| My child had what he/she wanted in life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 2.89 | −2.58 | −1.96 | −1.04 | 0.12 |

| My child had what he/she needed in life. | 1.98 | −3.32 | −2.76 | −1.67 | −0.45 | |

| My child got the things he/she wanted in life. | 2.36 | −3.08 | −2.12 | −1.02 | 0.23 | |

| My child felt that his/her life was better than most kids’ lives. | 2.29 | −2.31 | −1.71 | −0.70 | 0.43 | |

| My child enjoyed his/her life more than most kids enjoyed their lives. | 2.47 | −2.46 | −1.79 | −0.88 | 0.23 | |

| My child felt he/she lived as well as other kids. | 3.28 | −2.45 | −1.92 | −1.08 | −0.02 | |

| My child’s life was as good as most kids’ lives. | 2.29 | −3.02 | −2.40 | −1.46 | −0.34 | |

| My child was satisfied with the friends he/she has. | SF8b | 2.34 | −2.95 | −2.18 | −1.35 | −0.24 |

| My child was happy with his/her social life. | 2.74 | −2.74 | −1.93 | −1.15 | −0.15 | |

| My child was happy with his/her family life. | SF8b | 3.89 | −2.56 | −1.91 | −1.28 | −0.30 |

| My child was happy with his/her life at school. | 2.48 | −2.64 | −1.89 | −1.08 | 0.02 | |

| My child was happy with his/her life at home. | 3.82 | −2.44 | −1.98 | −1.25 | −0.23 | |

| My child was happy with life in his/her neighborhood. | SF8b | 2.29 | −2.68 | −1.96 | −1.04 | −0.06 |

| My child was happy with life in his/her community. | 3.54 | −2.59 | −1.99 | −1.10 | −0.02 | |

| My child was satisfied with his/her free time. | 2.82 | −2.78 | −1.99 | −1.18 | −0.05 | |

| My child was satisfied with his/her skills and talents. | SF8b | 2.29 | −2.85 | −2.16 | −1.30 | −0.08 |

| My child was satisfied with his/her life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 3.85 | −2.34 | −1.95 | −1.26 | −0.26 |

| My child felt extremely positive about his/her life. | 4.80 | −2.27 | −1.63 | −0.95 | −0.04 | |

| My child was happy with his/her life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 4.98 | −2.41 | −1.88 | −1.23 | −0.30 |

| My child felt very good about his/her life. | 6.35 | −2.38 | −1.85 | −1.23 | −0.28 | |

| My child felt good about his/her life. | 5.10 | −2.39 | −1.93 | −1.20 | −0.18 | |

| My child had a good life. | SF4a, SF8a, SF8b | 4.32 | −2.64 | −2.28 | −1.54 | −0.54 |

| My child felt positive about his/her life. | 4.96 | −2.32 | −1.90 | −1.20 | −0.23 | |

| My child had fun. | 4.02 | −2.62 | −2.09 | −1.38 | −0.32 | |

| My child had a lot of fun. | 3.68 | −2.70 | −2.04 | −1.30 | −0.31 | |

| My child enjoyed his/her life. | SF8b | 4.70 | −2.60 | −1.95 | −1.25 | −0.24 |

| My child liked the way he/she lived his/her life. | 5.20 | −2.51 | −1.98 | −1.18 | −0.11 | |

| My child’s life was worthwhile. | 2.15 | −3.62 | −2.87 | −2.01 | −0.84 | |

| My child’s life went well. | 4.82 | −2.85 | −2.18 | −1.38 | −0.32 | |

| My child felt he/she lived his/her life well. | 3.26 | −2.68 | −2.01 | −1.25 | −0.15 | |

| My child was satisfied with his/her life in general. | 4.88 | −2.51 | −1.98 | −1.29 | −0.33 | |

Note: SF4a: 4-item life satisfaction short form; SF8a: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional global life satisfaction items; and, SF8b: 8-item life satisfaction short form that includes the 4-item form and 4 additional context-specific life satisfaction items.

Table A3.

Scale-Level descriptive statistics, reliability, and concurrent validity, Parent-Proxy Edition

| Item Bank, 42 Items | SF8a, 8 Items | SF8b, 8 Items | SF4a, 4 Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Descriptive Statistics (Study 1, n=964) | ||||

| Range | 15.1–66.3 | 18.5–61.5 | 17.0–61.5 | 20.2–59.2 |

| Mean (SD) | 47.1 (9.8) | 47.3 (9.6) | 47.0 (9.5) | 47.0 (9.1) |

| Floor, n (%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Ceiling, n (%) | 71 (7.4%) | 187 (19.4%) | 168 (17.4%) | 241 (25.0%) |

|

| ||||

| Reliability | 0.88 | |||

| Marginal Reliability | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.83 |

| Test-Retest ICC (Study 1 Retest Sample, n=62) | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.81 | |

|

| ||||

| Convergent Validity with PROMIS Measures, Pearson’s r | ||||

| Positive Affect (Study 1, n=502) | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| Meaning and Purpose (Study 1, n=514) | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Peer Relationships (Study 2, n=1,294) | - | 0.55 | - | 0.52 |

| Physical Function-Mobility (Study 2, n=1,294) | - | 0.31 | - | 0.33 |

|

| ||||

| Discriminant Validity with PROMIS Measures, Pearson’s r | ||||

| Anger (Study 1, n=70) | −0.32 | −0.31 | −0.32 | −0.34 |

| Anxiety (Study 1, n=70) | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.15 | −0.14 |

| Depressive Symptoms 8a (Study 1, n=71) | −0.31 | −0.31 | −0.35 | −0.31 |

| Psychological Stress Experiences (Study 2, n=1,291) | - | −0.57 | - | −0.58 |

| Fatigue (Study 2, n=1,294) | - | −0.45 | - | −0.45 |

Table A4.

Correlates of parent-proxy reported life satisfaction from multivariable regression; data are from Study 2 and life satisfaction was measured with the SF8a.

| Covariate | Beta Coefficient (SE) | p-value | 95% CIs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intercept | 48.5 (0.6) | <0.001 | 47.2, 49.8 |

|

| |||

| Age, years | |||

| 8–12 | 2.1 (1.8) | 0.230 | −1.4, 5.7 |

| 13–17 | --- | ||

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | −0.9 (0.8) | 0.282 | −2.4, 0.7 |

| Male | --- | ||

|

| |||

| Age*Gender Interaction | |||

| 8–12 year-old females | 1.0 | 0.923 | −1.2, 3.3 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | --- | ||

| African-American or Black | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.464 | −1.2, 2.7 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3.7 (1.4) | 0.008 | 0.9, 6.4 |

| Other | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.621 | −1.3, 2.2 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.5 (0.8) | 0.074 | −0.1, 3.0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | --- | ||

|

| |||

| Family Income | |||

| <$40,000 per year | −1.7 (0.7) | 0.012 | −3.1, −0.4 |

| $40,000 or more per year | --- | ||

|

| |||

| Special Health Care Need | |||

| Yes | −4.5 (0.6) | <0.001 | −5.8, −3.3 |

| No | --- | ||

The dashes indicate the reference group.

Special health care need was measured using the Children with Special Health Care Needs screener, which identifies children with a chronic condition (medical and behavioral health disorders) that affects daily functioning or receipt of medical care services.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by an NIH grant U01AR057956 as part of the PROMIS initiative.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors has conflicts to disclose.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies described in this manuscript were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s human subjects institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: All parents provided informed consent for their children, and children themselves provided assent.

References

- 1.Shin DC, Johnson DM. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 1978;5:475–492. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diener E, Suh E, Lucas R, Smith H. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(2):276–302. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalos AC. Multiple discrepanices theory. Social Indicators Research. 1985;16(4):347–413. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz W. Multiple-discrepancies theory versus resource theory. Social Indicators Research. 1995;34(1):153–169. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Zumbo BD. Investigating the Substantive Aspect of Construct Validity for the Satisfaction with Life Scale Adapted for Children: A Focus on Cognitive Processes. Social Indicators Research. 2010;100(1):37–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council. Subjective Well-Being: Measuring Happiness, Suffering, and Other Dimensions of Experience. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adelman HS, Taylor L, Nelson P. Minors’ dissatisfaction with their life circumstances. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1989;20(2):135–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00711660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haranin EC, Huebner ES, Suldo SM. Predictive and Incremental Validity of Global and Domain-Based Adolescent Life Satisfaction Reports. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2007;25(2):127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besier T, Goldbeck L. Growing up with cystic fibrosis: achievement, life satisfaction, and mental health. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(10):1829–1835. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilman R, Huebner S. A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly. 2003;18(2):192. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zullig KJ, Valois RF, Huebner ES, Oeltmann JE, Drane JW. Relationship between perceived life satisfaction and adolescents’ substance abuse. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(4):279–288. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang JY, Wang KY, Ringel-Kulka T. Predictors of life satisfaction among Asian American adolescents-analysis of add health data. Springerplus. 2015;4:216. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng ZJ, Heubner ES, Hills KJ. Life Satisfaction and Academic Performance in Early Adolescents: Evidence for Reciprocal Association. Journal of School Psychology. 2015;53(6):479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bannink R, Pearce A, Hope S. Family income and young adolescents’ perceived social position: associations with self-esteem and life satisfaction in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(10):917–921. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matin N, Kelishadi R, Heshmat R, Motamed-Gorji N, Djalalinia S, Motlagh ME, et al. Joint association of screen time and physical activity on self-rated health and life satisfaction in children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-IV study. International Health. 2017;9(1):58–68. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihw044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maatta H, Hurtig T, Taanila A, Honkanen M, Ebeling H, Koivumaa-Honkanen H. Childhood chronic physical condition, self-reported health, and life satisfaction in adolescence. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;172(9):1197–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forrest CB, Tucker CA, Ravens-Sieberer U, Pratiwadi R, Moon J, Teneralli RE, et al. Concurrent validity of the PROMIS® pediatric global health measure. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(3):739–751. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huebner ES. Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International. 1991;12:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huebner ES. The Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale: An assessment of psychometric properties with black and white elementary school students. Social Indicators Research. 1995;34(3):315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadermann AM, Schonert-Reichl KA, Zumbo BD. Investigating Validity Evidence of the Satisfaction with Life Scale Adapted for Children. Social Indicators Research. 2009;96(2):229–247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin KA, Currie C. Reliability and Validity of an Adapted Version of the Cantril Ladder for Use with Adolescent Samples. Social Indicators Research. 2013;119(2):1047–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seligson JL, Huebner ES, Valois RF. Preliminary validation of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale (BMSLSS) Social Indicators Research. 2003;61(2):121–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funk I, Benjamin A, Huebner ES, Valois RF. Reliability and Validity of a Brief Life Satisfaction Scale with a High School Sample. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7(1):41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huebner E. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KD, Cunningham JD, Gilman R. Measuring Adolescent Life Satisfaction: A Psychometric Investigation of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS) Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;15(6):1333–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proctor C, Alex Linley P, Maltby J. Youth life satisfaction measures: a review. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(2):128–144. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Tucker C, Riley AW, Ravens-Sieberer U, Gardner W, et al. Commentary: the patient-reported outcome measurement information system (PROMIS(R)) for children and youth: application to pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37(6):614–621. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravens-Sieberer U, Devine J, Bevans K, Riley AW, Moon J, Salsman JM, et al. Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: presentation of first results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(2):207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forrest CB, Ravens-Sieberer U, Devine J, Becker BD, Teneralli RE, Moon J, et al. Development and Evaluation of the PROMIS® Pediatric Positive Affect Item Bank, Child-Report and Parent-Proxy Editions. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9843-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiSogra C, Dennis JM, Fahimi M. On the quality of ancillary data available for address-based sampling. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Section on Survey Research Methods. 2010:4174–4183. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennis JM. [Accessed June 6 2016];KnowledgePanel®: Processes & Procedures Contributing to Sample Representativeness & Tests for Self-Selection Bias. 2010 http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/docs/KnowledgePanelR-Statistical-Methods-Note.pdf.

- 33.Lohr S. Sampling: design and analysis. Nelson Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bethell CD, Read D, Neff J, Blumberg SJ, Stein REK, Sharp V, et al. Comparison of the children with special health care needs screener to the questionnaire for identifying children with chronic conditions--revised. Academic Pediatrics. 2002;2(1):49–57. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0049:cotcws>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein REK, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Academic Pediatrics. 2002;2(1):38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green BF, Bock D, Humphres RL, Linn MD. Technical Guidelines for Assessing Computerized Adaptive Tests. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1984;21(4):347–360. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor CL, Linley PA, Maltby J. Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;10(5):583–630. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Morgan Dewitt E, Irwin DE, et al. PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychology. 2013;32(10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1037/a0032670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, Beaumont JL, Amtmann D, Czajkowski S, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016;73:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irwin DE, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Lai JS, et al. PROMIS Pediatric Anger Scale: an item response theory analysis. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(4):697–706. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9969-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin DE, Stucky B, Langer MM, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Lai JS, et al. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(4):595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bevans KB, Gardner W, Pajer K, Riley AW, Forrest CB. Qualitative development of the PROMIS(R) pediatric stress response item banks. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013;38(2):173–191. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantril H. Pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edelen MO, Reeve BB. Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(Suppl 1):5–18. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carle AC. Mitigating systematic measurement error in comparative effectiveness research in heterogeneous populations. Medical Care. 2010;48(6 Suppl):S68–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d59557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samejima F. Graded response model. In: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of modern item response theory. New York, NY: Springer; 1997. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takane Y, de Leeuw J. On the relationship between item response theory and factor analysis of discretized variables. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):393–408. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Narasimhalu K, Lai JS, Cella D. Rapid detection of differential item functioning in assessments of health-related quality of life: The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(1):101–114. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millsap RE, Yun-Tein J. Assessing Factorial Invariance in Ordered-Categorical Measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(3):479–513. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi SW. Firestar: Computerized Adaptive Testing Simulation Program for Polytomous Item Response Theory Models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2009;33(8):644–645. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bock RD, Aitkin M. Marginal maximum likelihood estimation of item parameters: Application of an EM algorithm. Psychometrika. 1981;46:443–459. [Google Scholar]

- 54.PROMIS. [Accessed 22 March 2017];PROMIS Instrument Development and Psychometric Evaluation Scientific Standards. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/measure-development-research/119-measure-development-research.

- 55.Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(6):773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hays RD, Liu H, Kapteyn A. Use of Internet panels to conduct surveys. Behavioral Research. 2015;47(3):685–690. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0617-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Craig BM, Hays RD, Pickard AS, Cella D, Revicki DA, Reeve BB. Comparison of US panel vendors for online surveys. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15:e260. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]