Abstract

Aims

In response to concerns regarding resource expenditures required to fully implement the 2012 NIA-AA Sponsored Guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), we previously developed a sensitive and cost-reducing Condensed Protocol (CP) at the University of Washington (UW) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) that consolidated the recommended NIA-AA protocol into fewer cassettes requiring fewer immunohistochemical stains. The CP was not designed to replace NIA-AA protocols, but instead to make the NIA-AA criteria accessible to clinical and forensic neuropathology practices where resources limit full implementation of NIA-AA guidelines.

Methods and Results

In this regard, we developed practical criteria to instigate CP sampling and immunostaining, and applied these criteria in an academic clinical neuropathological practice. Over the course of one year, 73 cases were sampled using the CP; of those, 53 (72.6%) contained histologic features that prompted CP workup. We found that the CP resulted in increased identification of AD and Lewy body disease neuropathologic changes from what was expected using a clinical history-driven workup alone, while saving approximately $900 per case.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility and cost-savings of the CP applied to a clinical autopsy practice, and highlights potentially unrecognized neurodegenerative disease processes in the general aging community.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, academic hospital autopsy service, cost, age-related neurodegeneration, Condensed Protocol, neuropathology

Introduction

Definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other age-related neurodegenerative diseases, including Lewy body disease (LBD), requires autopsy confirmation. The latest guidelines for the neuropathological diagnosis of AD and related diseases were devised by a group of international experts organized by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, and were published in 2012 as the NIA-AA guidelines for the pathological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.1, 2 The guidelines recommend sampling 20 separate brain regions using diverse histochemical and/or immunohistochemical stains to characterize AD pathology according to amyloid plaque3 and neurofibrillary tangle4 distribution, neuritic plaque density,5 and other disease processes including cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), LBD (distribution), microvascular brain injury (microinfarct burden), and hippocampal sclerosis. Neuropathologists in AD Centers (ADCs) and other research settings have successfully implemented the NIA-AA guidelines, and the approach is quite effective for the diagnosis of a wide range of neurodegenerative disorders with a high specificity and sensitivity.6 However, non-ADC affiliated neuropathologists raised concerns that the approach had limited applicability due to its high cost burden, particularly in smaller academic or private practice and forensic pathology settings.

In response, our group designed the Condensed Protocol (CP) for the NIA-AA guidelines to enable application of the NIA-AA criteria in these settings.7 The CP maintains sampling from 20 recommended regions in the NIA-AA guidelines while reducing the number of paraffin blocks and routine stains (from 20 to 5, each), immunostains (from 13 to 3), and cost (by ~75%). The pooling of multiple samples into each block and the choice of the subsequent immunostain was strategically designed in such a way that maximum information regarding the severity and distribution of AD and LBD pathology could be obtained from a minimum number of blocks. We tested sensitivity and specificity of the CP in relation to the original (gold standard) NIA-AA guidelines retrospectively in 30 selected research autopsies and then prospectively in 20 consecutive research autopsies from the UW Neuropathology Core. We reported that CP maintained excellent specificity for lesions of AD, LBD, and microvascular brain injury (μVBI) as assessed by microvascular lesions (MVLs), and maintained excellent sensitivity for AD neuropathologic changes and moderate sensitivity for LBD. The CP had poor sensitivity for MVLs as we had anticipated.7

AD neuropathologic change is highly prevalent in the elderly, and is often accompanied by some degree of LBD and μVBI. Recognizing that routine hospital autopsies are unlikely to undergo complete NIA-AA sampling and workup, there may be some benefit over standard neuropathological practice to implement the CP in this setting to detect AD and LBD. We tested this by developing selection criteria relevant to a clinical autopsy practice to determine when to apply the CP protocol, and then implementing the selection process and CP over approximately one year to consecutive autopsies at the UW Medical Center (UWMC) in Seattle, Washington. Here we provide evidence for the feasibility of the CP in a large hospital-based autopsy service, where irrespective of clinical diagnosis, brain sections from each case age 65 years or older underwent CP sampling and screening using standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining; if pathologic features of neurodegeneration, such as amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, Lewy bodies, or other neurodegenerative features were identified on H&E, CP special stains were performed and complete CP examination undertaken.

Materials and methods

Case Selection

The use of human subject material was performed in accordance with guidelines set by the UW Institutional Review Board. Neuropathology faculty (PJC, LG-C, GJ-S, DAM, CDK), in conjunction with Neuropathology fellows (RB, MEF, CSL), perform complete neuropathologic examinations at a weekly UWMC Braincutting Conference as part of the routine clinical autopsy service. Except in rare circumstances, the brain from every adult autopsy is examined at this conference.

Tissue Sampling and Slide Preparation

In our original CP study,7 every case in the retrospective and prospective cohorts underwent the CP sampling and staining protocol. However, for a routine neuropathology practice where clinical neurological information is uncommon and there is an absence of research quality psychometric and other data, we recognized the need for a screening method and criteria to determine which cases underwent the full CP workup. Based on historical data from our institution, we recognized that age 65 or older, or clinical concern for dementia or neurodegenerative disease, represented inclusion criteria that would capture virtually all prior cases that underwent extensive neurodegenerative disease neuropathology workup. The CP sampling protocol was instituted in cases that met either of these criteria. Briefly, in addition to the 10 blocks that we submit for routine neuropathological examination of hospital autopsy cases, the 20 brain regions that are sampled in the detailed NIA-AA protocol were consolidated in 5 blocks exactly according to our published protocol.7 However, unlike our original study, special stains were not performed before first examining H&E-stained section from the 5 CP blocks (Figure 1). If neurodegenerative pathology or changes suspicious for neurodegeneration were identified in any of the H&E-stained sections, such as amyloid (A) β plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, Lewy bodies, Hirano bodies, granulovacuolar degeneration, hippocampal sclerosis, frank cortical neuron loss or gliosis, etc., CP protocol special stains were ordered and evaluated according to NIA-AA guidelines. Tissue processing and H&E, immunohistochemical, and Bielschowsky staining were performed according to standardized and validated protocols already established in the UW Department of Pathology.

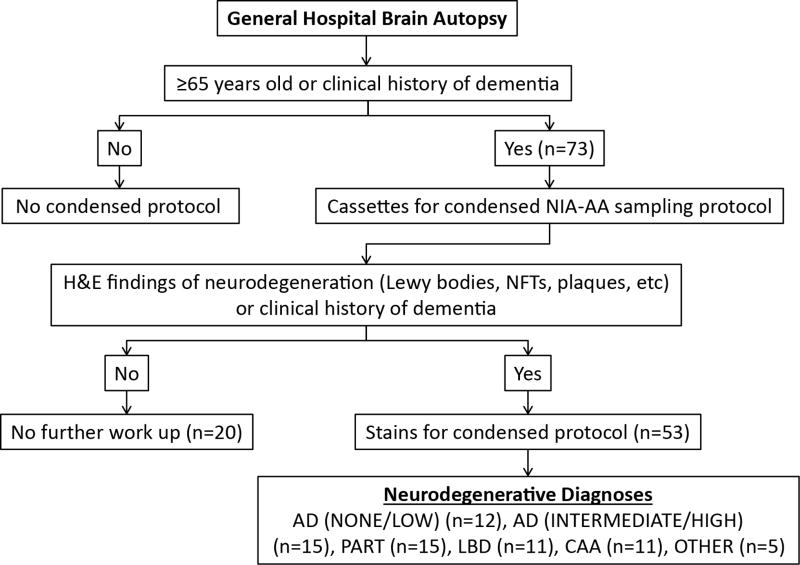

Figure 1.

Algorithm for NIA-AA condensed protocol (CP) work up in clinical autopsy practice. Abbreviations: H&E-hematoxylin and eosin; NFTs-neurofibrillary tangles; AD-Alzheimer disease; PART-primary age-related tauopathy; LBD-Lewy body disease; CAA-cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Detailed and diagrammed sections are described by Flanagan et al.7 Briefly, a section from a block containing cerebellar cortex, right caudate/internal capsule/putamen, right calcarine cortex and hemi-midbrain with substantia nigra and periaqueductal gray was stained with an anti-Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 6F/3D; 1:10 dilution; Dako/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) to detect Aβ plaque distribution for Thal phase (A score). A section from a block containing right hippocampus (including entorhinal and transentorhinal cortex), right superior frontal gyrus, right superior temporal gyrus, and left calcarine cortex was immunostained with an anti-tau mouse monoclonal antibody (clone Tau-2; 1:6000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to detect pathological tau-deposits including neurofibrillary tangle distribution to assign a Braak stage (B score). A section from a block containing left hippocampus, left superior frontal gyrus, left superior temporal gyrus, and right inferior parietal lobule was examined by Bielschowsky staining for CERAD neocortical neuritic plaque density (C score) and Braak stage (B score). Finally, a section from a block containing amygdala, cingulate gyrus; left inferior parietal lobule, and portion of dorsal pons with locus ceruleus was stained with anti-α-synuclein mouse monoclonal antibody (clone LB509; 1:1000 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to assess for Lewy body distribution. The fifth CP protocol block, containing left caudate/internal capsule/putamen, bilateral thalamus, and medulla was used, with other H&E-stained sections, to assess for microinfarcts and other pathology, but underwent no special stain.

Results

Postmortem brains from 73 cases from the general autopsy service were examined by the condensed NIA-AA protocol (Figure 1, Table 1). The age range was 59–94 years with a mean age of 73 years. The only patient below age 65 years in this series had a clinical history of dementia and was therefore included for CP. In this series, a majority (n = 47; 64%) of the patients were men. Most of the cases (n = 64; 88%) did not have formal neurologic evaluations, but a subset of decedents was diagnosed with either dementia (n = 3), mild cognitive impairment (n = 2), cognitive decline not otherwise specified (n = 2), or movement disorder (n = 2).

Table 1.

Clinical demographics of general autopsy cases at UW undergoing NIA-AA condensed protocol. MCI-Mild cognitive impairment.

| Age | 73 years (Mean) |

| 59–94 years (Range) | |

|

| |

| Sex | Male (n=47; 64%) |

| Female (n=26; 36%) | |

|

| |

| Clinical neurological diagnosis | Dementia (n=3; 4%) |

| MCI (n=2; 3%) | |

| Cognitive decline (n=2; 3%) | |

| Movement disorder (n=2; 3%) | |

| None (n=64; 88%) | |

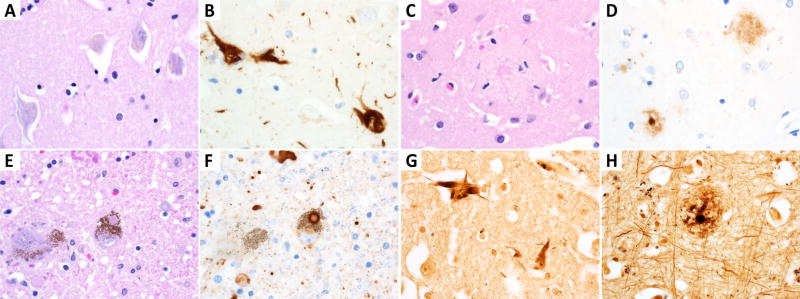

Of the 73 CP cases evaluated, 73% (n = 53) showed histopathologic features suspicious for neurodegeneration on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 1). These features included neurofibrillary tangles, extracellular plaques, Lewy bodies, Hirano bodies, granulovacuolar degeneration, or substantial cortical/hippocampal neuron loss/gliosis. These cases were examined further by immunostaining with antibodies described above and Bielschowsky staining according to the recently published protocol.7 Sections of the brain exhibited various neurodegenerative changes including neurofibrillary tangles (labeled by p-Tau antibody), neuritic plaques (labeled by p-Tau antibody and Bielschowsky stain) and Lewy bodies (highlighted by α-synuclein antibody). Representative photomicrographs of these histological structures are shown in Figure 2. AD pathology was graded according to the 2012 NIA-AA consensus recommendations, integrating Thal, Braak and CERAD scores using an ABC scoring system. These cases demonstrated various degrees of AD pathologic change, including high AD pathology in 5% (n = 4) of cases, intermediate AD pathology in 15% (n = 11), and low AD pathology in 10% (n = 7) of cases (Table 2). Of the 3 cases with a clinical diagnosis of dementia, one was a 94-year-old diagnosed pathologically with neurofibrillary tangle only dementia, one was an 80-year-old with high AD neuropathological change, and one was a 59-year-old with mixed pathology including brainstem predominant LBD, hippocampal sclerosis, vascular brain injury, and primary age-related tauopathy (PART). Among the 2 cases described clinically as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI), one was a 68-year-old with intermediate AD neuropathological change and the other was an 89-year-old with mixed pathologies including high AD neuropathological change, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), and neocortical (diffuse) LBD.

Figure 2.

Representative neurodegenerative histology in NIA-AA condensed protocol. Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the hippocampus are the most common finding as seen by (A) H&E and (B) Tau immunohistochemically stained slides. Cortical extracellular amyloid plaques are demonstrated with (C) H&E and (D) Aβ immunohistochemistry. Lewy bodies are present in (E) H&E and (F) α-synuclein immunostained slides of dopaminergic neurons. Bielschowsky silver stain highlights (G) hippocampal NFTs as well as (H) cortical neuritic plaques.

Table 2.

Neuropathological diagnoses for general UW autopsy cases undergoing NIA-AA condensed protocol. AD-Alzheimer disease; CAA-cerebral amyloid angiopathy; PART-primary age-related tauopathy; LBD-Lewy body disease; NFT-neurofibrillary tangle.

| Diagnosis | Ranking | Number of cases (n out of 73) |

|---|---|---|

| AD | None | n=5 (7%) |

| Low | n=7 (10%) | |

| Intermediate | n=11 (15%) | |

| High | n=4 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| CAA | n=11 (15%) | |

|

| ||

| PART | n=15 (21%) | |

|

| ||

| LBD | Brainstem-predominant | n=6 (8%) |

| Limbic (Transitional) | n=2 (3%) | |

| Neocortical (Diffuse) | n=1 (1%) | |

| Amygdala-predominant | n=2 (3%) | |

|

| ||

| NFT only dementia | n=1 (1%) | |

|

| ||

| Microvascular injury | n=3 (4%) | |

|

| ||

| Hippocampal sclerosis | n=1 (1%) | |

|

| ||

| Cases with ≥2 pathologies | n=14 (19%) | |

Neurodegenerative findings outside of AD neuropathological changes were frequently observed (Table 2). CAA was present in 15% (n = 11) of cases as assessed by the presence of Aβ in cerebral vasculature. PART was diagnosed in 21% (n = 15) of cases while LBD was present in 15% (n = 11) cases. The distribution of LB was brainstem predominant (n = 6), limbic (transitional) (n = 2), neocortical (diffuse) (n = 1), and amygdala-predominant (n = 2) (Table 2). There were 2 cases with a clinical diagnosis of a movement disorder, including a 77-year-old found to have intermediate AD changes and CAA (further extensive sampling and immunohistochemical workup outside of CP excluded additional etiologies including non-AD tauopathy) and an 84-year-old with brainstem-predominant LBD with intermediate AD changes. Overall, mixed neuropathologic processes (as defined by at least 2 co-morbid listed pathologic diagnoses) occurred in 19% (n = 14) of the cases examined with the full Condensed Protocol.

DISCUSSION

The CP for the NIA-AA guidelines for the pathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases was developed to reduce time and resources necessary to perform the recommended neuropathological assessment. The CP was envisioned for hospital and forensic autopsy practices that lack resources to perform the full NIA-AA workup, so we implemented the CP for neuropathology examinations of cases from an academic medical center (UWMC and affiliated hospitals) in our clinical practice. Recognizing the need for selection criteria to identify cases to undergo CP sampling and workup, we devised a stepwise CP implementation scheme in which decedents aged ≥65 or with a clinical suspicion for neurodegenerative disease underwent CP sampling and screening for neurodegenerative pathology on H&E slides; when neurodegenerative disease neuropathology was identified, three immunostains (Aβ, p-Tau, and α-synuclein) and a Bielschowsky silver stain were performed. We chose H&E screening to replicate our existing practice in which neurodegenerative disease workup was triggered with H&E pathology and to further control time and resource requirements.

The CP was not intended for, and does not perform as, a comprehensive replacement for the NIA-AA Guidelines for the neuropathological assessment of AD and related pathologies. However, this study confirms that the CP may be a reasonable alternative approach to assess AD neuropathologic change and LBD when resources are limited. We chose age 65 as a threshold to reflexively perform CP sampling, but we recognize that limiting the CP to cases with suspected dementia or neurological disease irrespective of age to further control resources may be more practical in some settings. Indeed, the CP enabled identification of neuropathologic changes sufficient to explain clinical dementia or cognitive impairment in all our cases.

As a cost effective measure for AD workup in the non-research setting, we have previously shown that the CP saves approximately $901.27 (78%) per case compared to the full NIA-AA workup.7 While the cost savings per case are evident, two confounds preclude the cost comparison for UW cases undergoing workup before and after implementation of our CP sampling protocol. First, the algorithm to include all cases age ≥65 was arbitrarily initiated for application of the CP in clinical practice and resulting CP sampling (in addition to routine blocks) almost certainly triggering a lower threshold for immunostaining. Second, out of the five practicing neuropathology faculty members at UW participating in the CP, only two were in practice at UW more than one year before implementation of the CP. Therefore, individual preferences and practices may have changed as faculty members were added. Outside of the cost effectiveness, an unexpected positive consequence of application of the CP in our clinical practice was increased consistency of sampling and examination of cases, and increased awareness by faculty and trainees, in general, regarding neuropathology of neurodegeneration.

Our study provides the first test of the utility of the Condensed NIA-AA Protocol outside the research setting, in a hospital-based general autopsy service. Our approach identified neurodegenerative changes in a large proportion of cases above what we recognized with previous, targeted assessments. We provided a comparison of the sensitivity and specificity between NIA-AA Guidelines and the CP in our original paper, 7 where we concluded that neuropathological analysis using the CP reduces the cost of analysis by 75% relative to the NIA-AA Guidelines without significant compromise in diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for AD and LBD. The specificity of the CP for all lesion types was above 85% whereas the sensitivity was variable for different lesions. For AD pathology, the sensitivity was > 80%. For LBD, the sensitivity was <60% for ranked evaluations (<60%) but increased to 80% using “any” vs “none” criteria. In the absence of a direct comparison with full and condensed protocols in the current patient population, the sensitivity and specificity of the Condensed Protocol for AD and LBD may be different from the original study in a research autopsy cohort. Thus, use of the CP has limitations compared with the NIA-AA Guidelines, but still provides an alternative that we have shown is feasible for the evaluation of AD, LBD, and hippocampal sclerosis in clinical or forensic practice in cases above a certain age or with suspected neurodegenerative disease.

We recognize Bielschowsky stains are expensive and not available to many labs. Silver stains are included in the CP as a convenient method to detect neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the same tissues, but silver stains are not required in the full NIA-AA guidelines. Indeed, the p-Tau block in the CP was designed to be sufficient to assess neurofibrillary degeneration according to the full NIA-AA guidelines and supported by studies by Braak et al8 using p-Tau immunohistochemistry.

Calcarine cortex was chosen in our original CP study7 as the cerebral cortex sample in the Aβ immunohistochemistry block in order to combine assessments for the presence of diffuse amyloid plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). We recognized that occipital cortex was optional for the full NIA-AA assessment, but Thal et al3 reported Aβ deposits in occipital cortex, in addition to frontal, parietal and temporal cortex, in Phase 1. Further, guidelines for the assessment of CAA either include occipital cortex9 or direct the assessment specifically to occipital cortex10 for sampling to assess contributions of cerebrovascular pathology to cognitive impairment. The Bielschowsky silver stain can be used to detect diffuse plaques (albeit with less sensitivity than IHC), and silver and PHF-tau stains can be used to detect neuritic plaques.

We previously reported that the most significant limitation of the CP lies in its poor sensitivity for the detection of microvascular lesions.7 These lesions are not grossly identifiable and are infrequent even in severe cases; thus, random detection of these lesions is highly dependent on the amount of tissue sampled. In addition to the 5 blocks submitted for the CP, we routinely examine 10 standard sections of brain (including bilateral basal ganglia) for each case using H&E stain. However, in cases with strong suspicion for MVL, if the above-mentioned approach does not identify a MVL, or in cases of suspected dementia in which pathologic changes sufficient to explain the clinical symptoms are not identified with the CP, more extensive sampling of brain areas can be performed for H&E stains at low cost. Microvascular brain injury is an important contributor to dementia; we have designed, but not tested, supplementary sampling to better align with NIA-AA guidelines to detect MVLs, but these protocols are untested. Modifications to CP beyond additional sampling may be needed to address this important issue in research and academic/community/forensic settings.

Similar to microvascular brain injury, reduced sampling area increases the probability that pathologic features will be missed in low burden Aβ cases. However, any sampling protocol, including the full NIA-AA guidelines, is susceptible to sampling error depending on the frequency of the pathologic feature in question. Additional studies are needed to determine thresholds for false negatives in the full and Condensed NIA-AA protocols to determine sensitivities for each pathologic feature in comparison with the other across a wide range of pathologic burden, but in the original Condensed Protocol study we did not see significant reduction in sensitivity of detection of amyloid pathology compared with NIA-AA protocols.

We recognize that the CP is not designed for diagnosis of other less common forms of neurodegenerative disease including frontotemporal lobar degeneration, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Niemann-Pick, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, etc. However, apart from CTE, these entities are so rare that savings from applying the CP would not justify application of the CP over usual diagnostic protocols. The CP, like the original NIA-AA guidelines, is not designed as a comprehensive assessment tool for diverse neurodegenerative diseases, but is designed as a first step to assess common (AD, LBD) neurodegenerative pathologies in association with cognitive impairment/dementia.

There has been marked variability in the approach towards neuropathological diagnosis of AD among different clinical practices. Our study presents a standardized approach for examination of neurodegenerative pathology that is pathologist independent and has been already validated to have a high level of agreement between pathologists.6

In every case with an established clinical diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or movement disorder, neuropathological changes sufficient to explain the clinical presentation were identified with the CP. In addition, we identified AD-related and other pathologies in several cases with no established diagnosis of dementia, cognitive impairment, or other neurological condition. Extensive clinico-pathologic correlation in these cases could not be performed due to the lack of detailed motor and cognitive examination/testing in these patients.

In addition to providing relevant clinical information for decedents’ families, the use of condensed NIA-AA protocol for general autopsy service also provides relevant information regarding the prevalence of AD pathology in an academic medical center population. Approximately 20% of cases examined in this study were diagnosed with intermediate to high AD pathology. Multiple studies have documented the presence of significant AD neuropathologic changes in the absence of cognitive impairment. Elobeid et al 11 reported, in a hospital-based study of non-demented patients, that 15% showed intermediate AD pathology according to the 2012 NIA-AA criteria.11 Bennett et al12 performed a large-scale study in which they examined the prevalence of AD pathology in 134 subjects without dementia using the NIH-Reagan criteria. Approximately 1.5% of the cases had high likelihood of AD and 35.8% had intermediate likelihood of AD.12 Similar results were obtained by Cholerton et al,13 who found a high number of cases with moderate neuritic plaques and Braak score of III-VI in cases without clinical dementia.13 Our study presents the first example for the use of the condensed NIA-AA protocol in a hospital-based population and lays the foundation for more sophisticated studies in future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Corrine Fligner, Ms. Jessica Malmberg, and the University of Washington Autopsy and After Death Services team for outstanding clinical and technical support, and Christine Federhart and Allison Beller for outstanding administrative support. Sources of support include: NIH P50 AG005136, P50 AG047366, and the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowment.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: PJC and CDK conceived and designed the study. PJC, MEF, CSL, LFG, GJS, TJM, DAM, and CDK participated in data collection. RB, PJC, and CDK analyzed and interpreted the data. RB, PJC, and CDK drafted the article. RB, PJC, and CDK critically revised the manuscript. RB, PJC, MEF, CSL, LGF, GJS, TJM, DAM, and CDK approved final version of manuscript for publication.

Ethics Statement: The use of human subject material was performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines set by the UW Institutional Review Board, including a waiver of informed consent.

References

- 1.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-alzheimer's association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-alzheimer's association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of alzheimer's disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of a beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of ad. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for alzheimer's disease (cerad). Part ii. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montine TJ, Monsell SE, Beach TG, et al. Multisite assessment of nia-aa guidelines for the neuropathologic evaluation of alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.07.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flanagan ME, Marshall DA, Shofer JB, et al. Performance of a condensed protocol that reduces effort and cost of nia-aa guidelines for neuropathologic assessment of alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Love S, Chalmers K, Ince P, et al. Development, appraisal, validation and implementation of a consensus protocol for the assessment of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in post-mortem brain tissue. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2014;3:19–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skrobot OA, Attems J, Esiri M, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment neuropathology guidelines (vcing): The contribution of cerebrovascular pathology to cognitive impairment. Brain. 2016 doi: 10.1093/brain/aww214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elobeid A, Rantakomi S, Soininen H, Alafuzoff I. Alzheimer's disease-related plaques in nondemented subjects. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66:1837–1844. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cholerton B, Larson EB, Baker LD, et al. Neuropathologic correlates of cognition in a population-based sample. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:699–709. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]