Abstract

Use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) may increase the involvement of young people with developmental disabilities in their healthcare decisions and healthcare related research. Young people with developmental disabilities may have difficulty completing PROMs because of extraneous assessment demands that require additional cognitive processes. However, PROM design features may mitigate the impact of these demands. We identified and evaluated six pediatric PROMs of self-care and domestic life tasks for the incorporation of suggested design features that can reduce cognitive demands. PROMs incorporated an average of 6 out of 11 content, 7 out of 14 layout, and 2 out of 9 administration features. This critical review identified two primary gaps in PROM design: (1) examples and visuals were not optimized to reduce cognitive demands; and (2) administration features that support young people’s motivation and self-efficacy and reduce frustration were underutilized. Because assessment demands impact the validity of PROMs, clinicians should prospectively consider the impact of these demands when selecting PROMs and interpreting scores.

Funding agencies, advocacy groups, and expert panels have called for increased involvement of all patients, including young people with developmental disabilities,* in healthcare decision making and healthcare related research.1,2 This emphasis on patient involvement has coincided with calls for increased ‘accessibility’ and equity in rehabilitation measurement and research.2 Use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) is one way rehabilitation professionals can increase the involvement of young people with developmental disabilities in their healthcare and healthcare related research.1 A PROM is an evaluation of ‘the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.’3 Young people with developmental disabilities often have cognitive impairments that can make it difficult to read, interpret, and respond to a PROM.4–6 Rather than discounting the ability of young people to use PROMs because of such impairments, clinicians and researchers should carefully consider how a PROM’s design may impact a young person’s ability to access PROMs, and subsequently, their involvement in healthcare decision-making and research.

Selecting an appropriate PROM for young people with developmental disabilities and related cognitive impairments requires an understanding of assessment demands, which are the specific skills and processes respondents must execute to complete a PROM. Young people with cognitive impairments may have difficulty meeting PROM assessment demands that require attention, working memory, long-term memory, and judgment, such as interpreting the meaning of an item and selecting a response category.7–9 When PROMs pose extraneous assessment demands, scores reflect respondents’ abilities to meet these demands, rather than their healthcare experiences and outcomes. Therefore, assessment demands that exceed the abilities of respondents threaten PROM validity.

Although assessment developers have addressed ways to reduce motor and perceptual demands of PROMs,2 there is no model for systematically evaluating demands related to cognitive processes (henceforth referred to as ‘cognitive demands’) and ensuring cognitive accessibility of PROMs. To fill this gap, we recently proposed a framework describing how specific PROM design features may be used to reduce cognitive demands.6 Based on extensive multidisciplinary evidence, the framework suggests three features that can reduce cognitive demands in PROMs. (1) Content features (11 features) address how linguistic complexity and the types of judgments required to interpret items impact the extent to which an item’s intended meaning is understood by a respondent. (2) Layout features (14 features) address how the arrangement of words, images, and rating scale(s) can increase or decrease the perceptual processes required to navigate a PROM. Extraneous perceptual demands can increase the overall cognitive demands associated with PROM completion. (3) Administration features (9 features) address how the procedures followed during PROM completion, by both the administrator and respondent, can be optimized to support attention and motivation.

In the present study, we apply this framework to evaluate pediatric PROMs of functional performance of self-care and domestic life tasks, as defined by the International Classification of Functioning – Children and Youth (ICF-CY).10 PROMs assessing self-care and domestic life tasks are important, as such tasks are primary outcomes of interest in rehabilitation,11,12 support participation in everyday life situations,13 and are highly valued by young people and parents. This study addressed the question: to what extent do pediatric PROMs of self-care and domestic life tasks incorporate design features that reduce cognitive demands? The results of this study may inform the selection of PROMs congruent with the abilities and needs of young people with developmental disabilities.

METHODS

We used systematic and replicable approaches to identify and select PROMs for inclusion in this study. We then applied the framework to critically evaluate each PROM for design features that reduce cognitive demands.6

Sampling

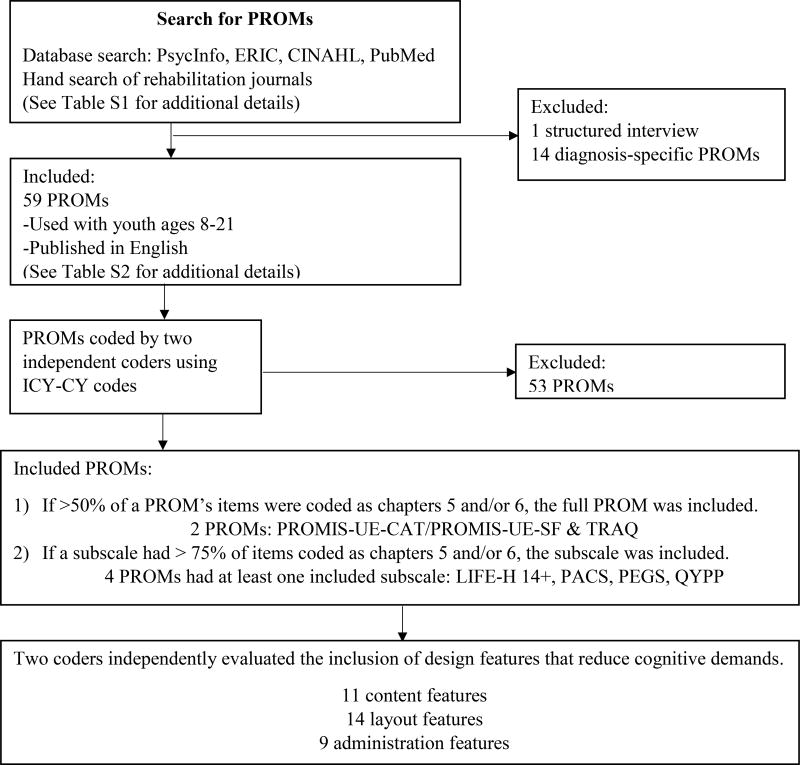

To identify pediatric PROMs of functional performance of self-care and domestic life tasks, we used indexing terms to search PsycInfo, ERIC, CINAHL, and PubMed from May to July 2014. We also reviewed the table of contents of key rehabilitation journals dated January 2012 to July 2014 (Table S1, online supporting information). The first author screened titles and abstracts to identify PROMs published in English and used with young people with disabilities aged 8 to 21. To identify PROMs that may be most broadly used, we excluded PROMs designed for specific health conditions (e.g. asthma) or diagnostic categories (e.g. cerebral palsy). Structured interviews (e.g. the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure) were excluded, because they do not contain discrete items (Fig. 1). As needed, we contacted assessment developers to determine if the PROM was for use with young people with disabilities.

Figure 1.

Summary of methods to identify and evaluate PROMs

PROM, Patient Reported Outcome Measure; ICF-CY, International Classification of Functioning – Children and Youth; PROMIS UE-CAT, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Computer Adaptive Test; PROMIS UE-SF, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Short Form; TRAQ, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire; LIFE-H 14+, Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+; PACS, Pediatric Activity Card Sort; PEGS, Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System; QYPP, Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation.

Items from all identified PROMs were entered into a spreadsheet. The first and second authors independently determined if each PROM’s items aligned with the ICF-CY definitions of self-care (chapter 5) and domestic life (chapter 6).10 As suggested by ICF linking rules, we applied ICF-CY codes to the most precise level possible;14 across PROMs, this was the second level of coding. PROMs were included in this study under one of two conditions: (1) if more than 50 percent of a PROM’s items were coded as chapters 5 and/or 6, the full PROM was included; (2) if a PROM subscale had more than 75 percent of items coded in these chapters, the subscale was included. For all included PROMs, we acquired PROM forms, manuscripts describing item pools, manuals, and/or administration instructions.

We applied ICF codes to 59 PROMs used with young people with disabilities (Table S2, online supporting information). Coders reviewed discrepancies and reached consensus for all items (average percent agreement before consensus: 76%, SD 17%, median: 81%). Six PROMs met inclusion criteria (Table I): two PROMs contained more than 50 percent of items coded as chapters 5 and/or 6 and four additional PROMs had subscales with more than 75 percent of items coded as chapters 5 and/or 6 of the ICF-CY.

Table I.

Included PROMs

| Materials evaluated in this study | Previous validation research | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROM | Assessed construct | Items or subscales included |

Number of items evaluated |

Format | Evaluated materials |

Age of participants in validation study |

Functional abilities of participants in validation studies |

| PROMIS UE-CAT28 | ‘Activities that require use of the upper extremity including shoulder, arm, and hand activities’30 | Full item bank | 28 | Computer, all 4 available formats | Online demo Online administration instructions | 5–17 | Individuals were excluded for medical or psychiatric conditions and/or other impairments (including cognitive) that would prevent PROM completion. |

| PROMIS UE-SF29 | Full assessment (short form represents items from the full CAT item bank) | 8 | Paper/pencil form | Paper/pencil short form Online administration instructions | No information was provided about participants’ IQ, literacy, or cognitive functioning. | ||

| TRAQ31 | Readiness for healthcare transition | Full assessment | 20 | Paper/pencil form | Paper/pencil form Online administration instructions | 14–26 | Participants had the following conditions:

|

| LIFE-H 14+32, 33 | Social participation | Diet, eating meals, meal preparation, personal care, elimination, dressing, healthcare, and household maintenance subscales | 68 | Paper/pencil form | Paper/pencil form Published manual | 14+ |

|

| PACS34 | Occupational performance and engagement | Personal care subscale | 12 | Card sort | Full assessment (card sort) Published manual | 5–14 | No information was provided about participants’ IQ, literacy, or cognitive functioning. |

| PEGS35 | Perceived competence in everyday activities | Self-care subscale | 7 | Card sort | Full assessment (card sort) Published manual | Chronologically or developmentally 6–9 |

|

| QYPP36, 37 | ‘Participation frequency across multiple domains’ | Home life subscale | 5 | Paper/pencil form | Paper/pencil form Development papers (dissertation, published manuscript) | 13–21 |

|

PROM, Patient Reported Outcome Measure; ICF-CY, International Classification of Functioning – Children and Youth; PROMIS UE-CAT, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Computer Adaptive Test; PROMIS UE-SF, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Short Form; TRAQ, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire; LIFE-H 14+, Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+; PACS, Pediatric Activity Card Sort; PEGS, Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System; QYPP, Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation.

Evaluation of cognitive assessment demands

The first and third authors independently coded each PROM for inclusion of each design feature (Tables II–IV).6 First, raters independently reviewed all available materials for each PROM. Next, raters coded the incorporation of each feature as ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ or ‘not applicable.’ If there was insufficient information to evaluate the feature, it was coded as ‘not explicit.’ When PROMs had multiple formats (e.g. short forms, computer), we evaluated each format independently. For the features ‘unfamiliar words’ and ‘simple language’ (see definitions in Table II), if a simpler synonym was identified by the Plain Language Thesaurus for Health Communications,15 the word was considered either unfamiliar or not simple. Otherwise, raters coded the item based on clinical experience working with young people with developmental disabilities. If a single word was considered unfamiliar or not simple, the whole item received a ‘no’ rating for this feature. For the feature ‘simple grammar,’ verb complexity was based on the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing’s definition: ‘complex verbs are multi-part with a base or main verb and several auxiliaries.’16 Sentence length and number of clauses was also considered for ‘complex grammar.’ Raters met to review discrepancies and reach consensus for each feature. When necessary, the second author provided input to resolve discrepancies. This novel coding approach required iterative refinement; therefore, it was not possible to calculate interrater reliability.

Table II.

Item content: the meaning conveyed in each item

| Accessibility featurea | Definition | PROMIS UE-CAT |

PROMIS UE-SF |

QYPP | TRAQ | PACS | PEGS | LIFE-H 14+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive wording | Item is free from modifiers or negative wording, such as ‘can’t’ ‘don’t’ ‘not’ ‘no’ or ‘except’ that would reverse the meaning of the rating scale. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Simple wording | Item uses concrete and shortest word(s) possible. | 96.4% | 100% | 40% | 65% | 100% | 100% | 63.2% |

| Familiar words | Item uses words that young people would be expected to have exposure to and understand. | 96.4% | 100% | 0% | 60% | 91.7% | 85.7% | 36.8% |

| Define unfamiliar wordsb | When item uses unfamiliar words and abbreviations for which there may be no simpler/more familiar synonyms, these words and abbreviations are defined. | 0/1 | n/a | 0/5 | 0/8 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/26 |

| Simple grammar | Item uses simple sentence structure and verbs (e.g. present or past simple). | 7.1% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92.9% | 94.1% |

| Contextual references | Item indicates specific interactions, locations, or activities within which measurement of the action or task is intended. | 0% | 0% | 100% (measure level) | 5% (item level) | 0% | 0% | 2.9% (item level) |

| Single concept | Item assesses single action or task; if the intended item meaning includes multiple actions or tasks, these tasks require similar physical and cognitive demands. | 85.7% | 87.5% | 40% | 75% | 75% | 100% | 51.5% |

| Evaluates self-perception | Item asks about self-perception and does not require respondent to hypothesize about other people’s thoughts or feelings. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Personal reference language | Item uses first or second person language to help respondent understand that the item is about them. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 22.1% |

| Evaluates current performance | Item assesses current behaviors and experiences (no recall time frames, specific frequencies, or comparison of current with past performance). | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Conceptually congruent visualsc | Items contains visuals that represent all actions and tasks intended for measurement and include only relevant information. | 0/1d | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6/11 | 1/7 | n/a |

| Conceptually congruent examplesc | If the item contains an example(s), the example(s) represents all actions or tasks intended for measurement. | n/a | n/a | 1/4 | 0/3 | n/a | n/a | 1/18 |

| Total applicable features included | Number of features that were incorporated in ≥80% of items | 6/10 (1 n/a) | 6/9 (2 n/a) | 6/10 (1 n/a) | 5/10 (1 n/a) | 6/10 (1 n/a) | 7/10 (1 n/a) | 4/10 (1 n/a) |

Percentages indicate presence of accessibility feature out of all items in the PROM unless otherwise specified.

Results indicate proportion of unfamiliar words and abbreviations that are defined out of the total number of items that include unfamiliar words and abbreviations.

Results indicate the proportion of items that contained the accessibility feature out of the total number of items for which the feature could be evaluated.

Applicable for two of four possible computer-based layouts. PROMIS UE-CAT, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Computer Adaptive Test; PROMIS UE-SF, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Short Form; QYPP, Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation; TRAQ, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire; PACS, Pediatric Activity Card Sort; PEGS, Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System; LIFE-H 14+, Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+.

Table IV.

Administration: the procedures followed by the respondent and the administrator to complete the PROM

| Accessibility featurea |

Definition | PROMIS UE-CAT |

PROMIS UE-SF |

QYPP | TRAQ | PACS | PEGS | LIFE-H 14+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching | Respondents learn how to use the PROM by reviewing example items or completing practice items. | N | N | Y (completed example) | N | N | Y (practice answering) | Y (multiple completed examples) | |

| Skip | Respondents are instructed to skip items that are not applicable to them/their experiences. | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | |

| Standards for paraphrasing or extended definitions | The PROM manual provides extended standardized, descriptions of the intended item meaning. These descriptions may be used to paraphrase or provide additional information if requested/needed by the respondent. | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | |

| Encourage respondent | The respondent receives positive feedback or encouragement during the self-report process. | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| Self-paced | The PROM can be completed without time restrictions. | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Validate respondent | The respondent is assured that the PROM is about his or her perspectives, perceptions, or feelings. | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |

| Content individualization | The PROM provides respondents with the opportunity to individualize some aspect of the PROM. | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | |

| Reading | The PROM items can be communicated without reading to oneself | NE | NE | NE | NE | Y | Y | NE | |

| Responding with alternative methods | The PROM items can be responded to using a variety of methods. | NE | NE | NE | NE | Y | Y | NE | |

| Total features included | 0/9 | 0/9 | 2/9 | 1/9 | 2/9 | 6/9 | 3/9 | ||

Results indicate presence (Y) or absence (N) of the accessibility feature at the measure level. When features could not be evaluated, we have reported ‘not explicitly present’ (NE). PROMIS UE-CAT, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Computer Adaptive Test; PROMIS UE-SF, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Short Form; QYPP, Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation; TRAQ, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire; PACS, Pediatric Activity Card Sort; PEGS, Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System; LIFE-H 14+, Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+.

Data analysis

For suggested features that applied to individual items (e.g. familiar words), we calculated the percent of items in the PROM that incorporated the feature (coded as ‘yes’). For suggested features that applied to the layout or administration procedures (e.g. font size), we report the presence of the feature in the PROM as ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘not applicable,’ or ‘not explicit.’

RESULTS

The results discuss each suggested feature in their order of appearance in Tables II to IV.

Item content

On average, PROMs incorporated six suggested content features in more than 80 percent of items (range: 4–7; for most PROMs only 10 of the 11 suggested features were applicable) (Table II).

All PROMs used positive wording. Positively worded items that avoid prefixes (e.g. ‘sad’ instead of ‘unhappy’) are easy to understand.17 When items are worded negatively, it may reverse the meaning of rating scales and be more difficult to interpret.18 PROMs were inconsistent in their use of other content features. For example, PROMs ranged in their use of simple and familiar words. When unfamiliar words (e.g. ‘referral,’ ‘orthoses’) were used, no PROM defined these words. Five PROMs consistently used simple grammar. The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Upper Extremity computer adaptive test and short form had the most complex grammar, as most items used the structure, ‘I could [functional task]’; ‘could + verb’ is a complex verb structure that may be difficult for young people with developmental disabilities to understand.16 This complex structure may be related to the PROMIS Upper Extremity’s incorporation of a recall period.

Cognitive demands are increased when PROMs do not place limits on the contexts, tasks, people, and time period to consider when responding to each item. For example, if a PROM item assesses a task that is conducted across several contexts (e.g. wash hands), young people must first evaluate their performance of the task in each context, and second, use judgment to identify the single rating that best reflects their performance across contexts.7,18 Only the Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation Home Life subscale limited the context by incorporating the directions, ‘This section asks questions about your life at home.’ Similarly, items that evaluate multiple concepts (i.e. double-barreled items) require respondents to evaluate their performance of multiple tasks for which their performance may vary. All PROMs except the Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System included at least one double-barreled item. While all PROMs asked young people to report self-perceptions of their performance rather than speculate how others perceive their performance, only three PROMs consistently used first (‘I’) or second person (‘you’) language to help the respondent understand the item is about him or her. Five PROMs asked young people to evaluate current performance. Evaluating current performance, rather than performance over a recall period, decreases cognitive demands related to memory.

Many PROMs did not optimize the use of visuals and examples to support young people’s understanding of item meaning. Visuals were used in the Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System and the Pediatric Activity Card Sort, but few of these visuals were congruent with the meaning of the written item. There were three ways in which visuals were incongruent with written items. First, sometimes visuals presented only one step of a multistep task. For example, the Pediatric Activity Card Sort item ‘bathing/showering’ shows a child turning on water, which is only one step of this task. Second, sometimes visuals were used in lieu of a written example: the Pediatric Activity Card Sort item about ‘buttoning’ included a picture of a child buttoning pants; however, there are several other items young people may button. In both situations, the visuals fail to represent the breadth of the intended item meaning, possibly leading to narrow and incorrect interpretation of the item. Third, some items used visuals depicting concrete actions or outcomes to represent a process or feeling. This led to incongruences between the images and the intended construct of measurement. For example, one Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System item evaluates respondents’ competence for tying shoes. Young people respond by identifying if they are most like a child who ‘can tie shoes easily’ or ‘has problems tying shoes,’ with accompanying pictures of a child with tied and untied shoes respectively. While the written item describes difficulty, the visual suggests that the item is measuring task completion, a different construct. When visuals and written items do not match, young people may misinterpret the item’s meaning.

While examples were infrequently used to provide additional information about an item’s intended meaning, when present, only 0 to 25 percent were congruent with the intended item meaning. Examples were coded as incongruent when they did not represent the full breadth of the intended construct of measurement. The example used in the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire item, ‘Do you call the doctor about unusual changes in your health (For example: allergic reactions)?’ may imply the item only intends to assess the ability to call the doctor for allergic reactions, rather than for all unusual health changes. In contrast, the examples in the Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation item, ‘I make food and drink that I heat up (e.g. hot drinks or food heated in a toaster, microwave or oven),’ describes all ways that food and drink can be heated.

Layout

PROMs included an average of seven suggested layout features (range: 5–10; 10–12 of the 14 suggested layout features were applicable to each PROM) (Table III). Most PROMs included legible and simple typeface, at least 12-point font, and simple punctuation. However, only the PROMIS Upper Extremity – computer adaptive test, in which the computer-administration presented one item per screen, included sufficient whitespace. Lack of white space requires respondents to visually process many pieces of information simultaneously, making it difficult to attend to individual items.9,19,20

Table III.

Layout: the arrangement of words, images, and response options

| Accessibility featurea |

Definition | PROMIS UE-CAT |

PROMIS UE-SF |

QYPP | TRAQ | PACS | PEGS | LIFE-H 14+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legible fontb |

|

|||||||

| Item | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Rating scale | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Simple typefaceb |

|

|||||||

| Item | 100% | 100% | 40% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Rating scale | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Size of font | Minimum 12 pt | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Simple punctuation | Avoid confusing punctuation, such as semicolons, hyphenated words, or sentences broken up with too many commas. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 90%c | 75%c | 100% | 100% |

| White space: overall ratingb | Y | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | N | |

| 1 inch margins | Y | Y | Y | N | n/a | n/a | Y | |

| ½ in between items and all associated content (e.g. images) | Y | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | N | |

| 35% white space | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | n/a | N | |

| Visual integration of items with rating scale | The item and rating scale are visually close to each other. | 100% | 12.5% | 100% | 5% | 100% | 100% | 7.4% |

| Visual integration of rating scale images | Images associated with rating categories are available next to all rating category options. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Visual integration of item stem with item | The item stem and item are visually close to each other. | 100% | 12.5% | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Text adjacent to images | Text is next to, above, or below images (not wrapped around, superimposed on, or distant from associated images). | 100%d | n/a | n/a | n/a | 100% | 100% | n/a |

| Consistent layout | All items and rating scales are formatted the same throughout the PROM. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Consistent use of color | If used, color is used consistently and supports cognitive processes. | Ye | n/a | n/a | n/a | Y | n/a | Y |

| Visual contrast | Colors are chosen for increased contrast. | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Left justification | Text is left justified | |||||||

| Item | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| Rating scale | N (2 of 4 possible layouts) | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| Multiline text is 3–5 inches per linef | If item text scrolls across two lines, each line of text is 3–5 inches. | n/ag | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/9 | n/a | 1/13 | 2/22 |

| Total applicable features included | Number of features that were incorporated in the overall layout or in ≥80% of items | 10/12 (2 n/a) | 5/11 (3 n/a) | 5/10 (4 n/a) | 6/10 (4 n/a) | 7/10 (4 n/a) | 8/10 (4 n/a) | 6/11 (3 n/a) |

Percentages indicate presence of accessibility feature out of all items in the PROM. Measure-level features are reported as ‘Y’ for presence of the feature, ‘N’ for absence of the features, and ‘n/a’ for instances when the features was not applicable (e.g. the PROM did not have any images).

PROM must meet criteria in all subcategories to be counted as ‘Y’ for total applicable features.

Items included ‘/’.

Applicable for two of four possible computer-based layouts.

Applicable for three of four possible computer-based layouts.

Results indicate proportion of items that contained the accessibility feature out of the total number of items for which the feature could be evaluated.

Computer-based assessment has adjustable line length. PROMIS UE-CAT, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Computer Adaptive Test; PROMIS UE-SF, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Upper Extremity – Short Form; QYPP, Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation; TRAQ, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire; PACS, Pediatric Activity Card Sort; PEGS, Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System; LIFE-H 14+, Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+.

PROMs can reduce the need to visually scan and shift attention between PROM items, rating scales, and images by placing these components adjacent to each other (i.e. visual integration). Three PROMs did not visually integrate item stems (e.g. ‘In the past 7 days…’), items, and rating scales. However, all PROMs that included images placed these images adjacent to text. PROMs varied in their incorporation of other features that support effective visual scanning. All PROMs used consistent layouts and both PROMs that used color used it consistently to support comprehension. However, three PROMs had insufficient visual contrast (e.g. black font on grey background). Four PROMs left justified all item text, but only one PROM left-justified rating scale text. When items included more than one line of text, most PROMs did not adhere to the recommendation that each line of text be 3 to 5 inches long.16,19

Administration

Many administration features were difficult to evaluate because PROMs did not have a manual or the manual did not provide explicit administration procedures. On average, PROMs included two suggested administration features (range: 0–6) (Table IV). These features reduce cognitive demands in two ways. First, they directly support cognitive processes by providing additional direction and clarification during administration. Three PROMs provided additional direction by teaching respondents how to use the PROM via example or practice items. Only the Life Habits Questionnaire for ages 14+ provided instructions to skip irrelevant items; directing young people to skip irrelevant items reduces measurement error caused by uncertainty.7,18,21 The Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System was the only PROM that included standardized definitions to clarify intended item meaning.

Second, other administration features support young people’s motivation and self-efficacy and reduce frustration during administration, which can bolster young people’s attention and facilitate their persistence to execute the processes required for meaningful PROM responses. No PROM included explicit instructions to encourage respondents or to direct respondents to complete the PROM at their own pace; both of which can support motivation and reduce frustration. All PROMs except the PROMIS Upper Extremity and the Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System incorporated validation by explicitly instructing young people to share their perspective. Young people’s self-efficacy and motivation is also supported when PROM content and formats can be individualized to young people’s needs and experiences. The Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System was the only PROM to provide content individualization, as it included one optional item for wheelchair users. PROMs with administration formats other than paper and pencil forms, such as the two card sorts (Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System and Pediatric Activity Card Sort), allow young people to respond to the PROM with methods other than reading and writing; this can reduce frustration for young people with literacy and fine motor difficulties.

DISCUSSION

We found that currently available pediatric PROMs assessing self-care and domestic life tasks that are valid and reliable for young people with a range of functional abilities (Table I) varied in their inclusion of suggested design features that may decrease cognitive demands for young people with developmental disabilities and related cognitive impairments. These results suggest that many PROMs may not be designed to optimize accessibility for young people with developmental disabilities, potentially threatening the validity of PROM scores. Invalid scores may lead to inappropriate clinical decisions or inaccurate inferences from research outcomes.22 Accordingly, rehabilitation clinicians and researchers need to think critically about their selection of PROMs for use with young people with developmental disabilities.

Our evaluation identified two primary gaps in PROM design: (1) examples and visuals were not optimized to reduce cognitive demands; and (2) suggested administration features that address motivation, self-efficacy, and frustration were underutilized.

Visuals and examples can help respondents understand the intended meaning of the item and more effectively draw upon relevant life experiences during self-evaluation.8,9 However, many PROM examples and visuals did not depict the breadth of the intended item or were abstract representations of the intended item. Young people with developmental disabilities often have difficulty interpreting and generalizing abstract representations of constructs.5,7 As a result, visuals and examples that do not fully represent the intended breadth of the item may lead to inaccurate and narrow item interpretations.16 Additionally, when written items and visuals present different or conflicting information, young people may be confused about the ‘correct’ item meaning. Furthermore, young people with lower literacy skills who rely more on visuals may not have complete information about the item. In all of these cases, incongruent visuals present cognitive demands that make it difficult for young people to validly interpret and respond to PROM items.9 Technology-driven approaches may resolve the challenge of creating visuals that reduce cognitive demands. While it may be impossible to create a single visual representing an item with a broad meaning (e.g. ‘cook’) or that requires several steps (e.g. ‘bathing’), computer-delivered PROMs could include a series of images or a video depicting each step.

Our second main finding was that PROMs incorporated few administration features that may support young people’s motivation and self-efficacy and reduce frustration while completing PROMs. Young people with developmental disabilities may have less experience completing PROMs. As a result, they may have anxiety about the purpose and consequences of the information they are sharing, perceive the PROM as a test with a ‘correct’ answer, and/or become discouraged because of the high cognitive demands of self-reporting.21 This can decrease young people’s ability to perform cognitive processes associated with self-reporting.23 As a result, young people may provide acquiescent responses (saying ‘yes’ or providing affirmative responses to all items), which significantly threatens validity.7,18,21 To support motivation and self-efficacy, assessment developers can explicitly incorporate features such as encouragement, self-pacing, and content and response format individualization in administration instructions.4,5,24 Further, since the literature documents concern the abilitity of young people with developmental disabilities to understand how to use rating scales,5 providing teaching, practice, or example items may be critical to ensure young people’s comprehension and reduce frustration.

Clinicians and researchers have several options for confronting the described gaps in PROM design. First, to select PROMs that match each young person’s unique needs and strengths, clinicians may use the present evaluation or conduct their own evaluation of PROMs to identify the most appropriate PROM for a specific client or clinical population, given their cognitive support needs. Second, clinicians may modify PROMs to incorporate some of the suggested features, such as increasing font size and defining unfamiliar words.24 However, these retroactive modifications and solutions have unknown impacts of PROM validity and are thus less preferable to prospectively designing PROMs to reduce cognitive demands. Third, clinicians may use a ‘think-aloud’ approach during administration to check young people’s interpretation of items.25 When young people do not interpret items in the intended manner, their resultant scores should be interpreted with caution.

Future research and limitations

Several limitations should be recognized. First, because new measures are frequently developed, we may not have identified all pediatric PROMs of self-care and domestic life tasks. Second, the functional abilities of young people (e.g. IQ, literacy, cognitive functioning) with whom identified PROMs were validated is underreported in the literature; this limited our ability to identify whether or not PROMs were designed to be used specifically by young people with developmental disabilities and related cognitive impairments. Third, we used a novel approach to evaluate PROM demands that has not been empirically validated.6 Although we have suggested that rehabilitation clinicians may use the suggested accessibility features as a guide to evaluate and select PROMs, further research is needed to examine the utility and effectiveness of this approach in practice.

Best practices in PROM development include involvement of intended respondents. Typically, focus groups and cognitive interviews are used to elicit important information about PROM content, item interpretation, and usability. When young people with developmental disabilities participate in focus groups and cognitive interviews, they can provide feedback on the effectiveness and experience of interacting with PROMs that incorporate these design features. Young people’s input may also be used to optimize PROM design. For example, when young people are engaged in identifying and evaluating item content and/or item wording in focus groups and/or cognitive interviews, they may be able to provide item phrasing that incorporates simple and familiar words.26 After this qualitative work, validation research must explore PROM validity and reliability when used with young people with developmental disabilities. Validation research should investigate changes in psychometric quality when features are and are not included, and how inclusion of the features differentially impacts psychometric quality when used by young people with varying characteristics (e.g. age), diagnoses (e.g. autism, cerebral palsy), and functional abilities (e.g. literacy, communication skills, IQ). Inclusion of young people with developmental disabilities in the validation phase is critical, as this group has typically not been included in this phase of research, even when measures are designed to be used with young people with disabilities (Table I).

Conclusions

We identified six PROMs that evaluate young people’s performance of self-care and domestic life tasks. These PROMs do not comprehensively include suggested features that decrease cognitive demands and thereby increase the access of young people with developmental disabilities to healthcare decision making and evaluation. Clinicians and researchers should carefully consider PROM design features when selecting and developing PROMs for use in practice or research with young people with developmental disabilities.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds

Patient reported outcome measure (PROM) design features can reduce assessment demands related to cognitive processes.

Pediatric PROMs underutilize design features that decrease cognitive demands of self-reporting.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Cathryn Ryan and Dr. Wendy Coster for their help conceptualizing the analysis.

Funding support provided by the Comprehensive Opportunities in Rehabilitation Research Training (CORRT), National Center Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institute Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (K12 HD055931).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ICF-CY

International Classification of Functioning – Children and Youth

- PROM

Patient reported outcome measure

- PROMIS

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Footnotes

Terminology varies over time and across contexts. Here, we use the term ‘developmental disability’ to describe individuals who have a disability attributable to a mental and/or physical impairment with onset before 22 years of age that is expected to continue throughout the life course and who need support in at least three areas of ‘major life activities,’ as defined by the United States Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act. 27

The following additional material may be found online:

Appendix S1: References for included PROMs

Table SI: Search terms and strategy

Table SII: Reviewed PROMs

Table SIII: Supporting evidence and resources for design features

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312:1513–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harniss M, Amtmann D, Cook D, Johnson K. Considerations for developing interfaces for collecting patient-reported outcomes that allow the inclusion of individuals with disabilities. Med Care. 2007;45(Suppl. 1):S48–54. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250822.41093.ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration. [accessed 10 June 2014];Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims [Internet] 2009 Available from: www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf.

- 4.Yalon-Chamovitz S. Invisible access needs of people with intellectual disabilities: a conceptual model of practice. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;47:395–400. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.5.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White-Koning M, Arnaud C, Bourdet-Loubère S, Bazex H, Colver A, Grandjean H. Subjective quality of life in children with intellectual impairment - how can it be assessed? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:281–5. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer JM, Schwartz A. Reducing barriers to Patient Reported Outcome Measures for people with cognitive impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujiura GT. RRTC Expert Panel on Health Measurement. Self-reported health of people with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50:352–69. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan RP, Burling KS, Rose D, et al. [accessed 10 June 2014];Universal Design for Computer-Based Testing (UD-CBT) guidelines. 2013 Available from: http://images.pearsonassessments.com/images/tmrs/TMRS_RR_UDCBTGuidelinesrevB.pdf.

- 9.Beddow PA. Accessibility theory for enhancing the validity of test results for students with special needs. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2012;59:97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: children & youth version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to physical therapist practice 3.0 [Internet] Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2014. [accessed 20 June 2016]. Available from: http://guidetoptpractice.apta.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Occupational Therapy Association. therapy practice framework: domain and process (3rd edition) Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(Suppl.1):S1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.James S, Ziviani J, Boyd R. A systematic review of activities of daily living measures for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:233–44. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustün B, Stucki G. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:212–8. doi: 10.1080/16501970510040263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Marketing. Plain language thesaurus for health communications. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abedi J, Leon S, Kao J, et al. Accessible reading assessments for students with disabilities: the role of cognitive, grammatical, lexical, and textual/visual features. CREST Report 785. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haladyna TM, Downing SM, Rodriguez MC. A review of multiple-choice item-writing guidelines for classroom assessment. Appl Meas Educ. 2002;15:309–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlay WM, Lyons E. Methodological issues in interviewing and using self-report questionnaires with people with mental retardation. Psychol Assess. 2001;13:319–35. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simply put: a guide for creating easy-to-understand materials. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman MG, Bryen DN. Web accessibility design recommendations for people with cognitive disabilities. Technol Disabil. 2007;19:205–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlay WM, Lyons E. Acquiescence in interviews with people who have mental retardation. Ment Retard. 2002;40:14–29. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0014:AIIWPW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coster WJ, Ni P, Slavin MD, et al. Differential item functioning in the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pediatric short forms in a sample of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:1132–8. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark R, Nguyen F, Sweller J. Efficiency in learning: evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer JM, Heckmann S, Bell-Walker M. Accommodations and therapeutic techniques used during the administration of the Child Occupational Self Assessment. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75:495–502. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velozo CA, Seel RT, Magasi S, Heinemann AW, Romero S. Improving measurement methods in rehabilitation: core concepts and recommendations for scale development. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:S154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddy L, Khastou L, Cook KF, Amtmann D. Item selection in self-report measures for children and adolescents with disabilities: lessons from cognitive interviews. J Pediatr Nurs. 2011;26:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Developmental disabilities assistance and bill of rights act of 2000. 42 USC 15001. Public Law. 2000:106–402. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varni JW, Magnus B, Stucky BD, et al. Psychometric properties of the PROMIS® pediatric scales: precision, stability, and comparison of different scoring and administration options. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1233–43. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeWitt EM, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: built using item response theory. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [accessed 20 June 2016];Physical function: A brief guide to the PROMIS physical function instruments. Available at: www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%Physical%Function%Scoring%Manual.pdf.

- 31.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ—Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36:160–71. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fougeyrollas P, Noreau L, Beaulieu M, et al. Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H 3.0) Quebec, Canada: International Network on the Disability Creation Process; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boucher N, Fiset D, Lachapelle Y, Fougeryrollas P. Projet d’expérimentation de la MHAVIE en sites-pilotes des centres de réadaptation en déficience physique et intellectuelle, trouble envahissant du développement et des centres de santé et de services sociaux, volet soutien à domicile: Rappot final. Quebec, Canada. Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux Direction adjointe des personnes ayant des déficiences; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandich AD, Polatajko HJ, Miller LT, Baum C. Pediatric activity card sort (PACS) Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Association for Occupational Therapists; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Missiuna C, Pollock N, Law M. The perceived efficacy and goal setting system. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuffrey CT. he development of a new instrument to measure participation of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle upon Tyne; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuffrey C, Bateman BJ, Colver AC. The Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation (QYPP): a new measure of participation frequency for disabled young people. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:500–11. doi: 10.1111/cch.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.