Abstract

Hepatic osteodystrophy is multifactorial in its pathogenesis. Numerous studies have shown that impairments of the hepatic growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 axis (GH/IGF-1) are common in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and chronic cholestatic liver disease. Moreover these conditions are also associated with low bone mineral density (BMD) and greater fracture risk, particularly in cortical bone sites. Hence, we addressed whether disruptions in the GH/IGF-1 axis were causally related to the low bone mass in states of chronic liver disease using a mouse model of liver-specific GH-receptor (GHR) gene deletion (Li-GHRKO). These mice exhibit chronic hepatic steatosis, local inflammation, and reduced BMD. We then employed a crossing strategy to restore liver production of IGF-1 via hepatic IGF-1 transgene (HIT). The resultant Li-GHRKO-HIT mouse model allowed us to dissect the roles of liver-derived IGF-1 in the pathogenesis of osteodystrophy during liver disease. We found that hepatic IGF-1 restored cortical bone acquisition, microarchitecture, and mechanical properties during growth in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, which was maintained during aging. However, trabecular bone volume was not restored in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. We found increased bone resorption indices in vivo as well as increased basal reactive oxygen species and increased mitochondrial stress in osteoblast cultures from Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT as compared to control mice. Changes in systemic markers such as inflammatory cytokines, osteoprotegrin, osteopontin, parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, or carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks, could not fully account for the diminished trabecular bone in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. Thus, the reduced serum IGF-1 associated with hepatic osteodystrophy is a main determinant of low cortical but not trabecular bone mass.

Keywords: growth hormone receptor, micro-CT, dyslipidemia, parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, osteoprotegrin, osteopontin

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic osteodystrophy refers to bone loss and fractures associated with liver disease. Growing epidemiological evidence links metabolic liver diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), to reduced bone mineral density (BMD) [1–6]. Patients with chronic viral hepatitis [7], liver cirrhosis [8–12], or chronic cholestatic liver disease [13, 14] also show low BMD. Studies indicate that bone health is directly related to the duration and severity of the liver disease. Hence patients with early stage liver disease manifest mainly with trabecular bone loss, while patients with progressive, more severe disease, exhibit features of osteoporosis and osteomalacia with increases in osteoid (unmineralized) area [2, 15–19]. There is an alarming increase in the incidence of obesity-associated NAFLD among the pediatric population in the US [20–22]; Specifically, 30% of children are obese and obesity is maintained in 80% of adolescents through adulthood [23]. A recent study has shown that hepatic fat content in children with known or suspected NAFLD positively associated with bone marrow fat content which could also impact skeletal integrity [24]. [1, 3–6, 25, 26]. More studies are needed to explore the long-term consequences of liver disease and NAFLD on bone health.

Liver disease impairs the somatotropic axis and associates with liver growth hormone (GH) resistance and reductions in serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), both of which are established regulators of bone acquisition during growth [27]. In rodents, GH resistance due to liver specific ablation of the GHR [28, 29], its mediators, the Janus kinase-2 (JAK2) [30, 31], or signal transducer and activator of transcription-5 (STAT5) [32] results in NAFLD, reductions in serum IGF-1, and severe osteopenia [29]. We have previously shown that hepatic derived IGF-1 regulates diaphyseal bone growth and is an important determinant of bone strength [33, 34]. Accordingly, low levels of serum IGF-1 (produced mainly by the liver) result in decreased radial bone growth producing slender and mechanically inferior bone phenotype [33, 34], while high levels of serum IGF-1 increase radial bone growth leading to the development of more robust bones [35–38]. Liver disease associated with GH insensitivity can lead to significantly reduced serum IGF-1. However, it is yet unknown whether osteopenia in liver diseases caused solely by the reductions in liver production of circulating IGF-1, or whether liver GHR regulates bone metabolism via hepatic mediators other than IGF-1.

We recently created a combined mouse model with liver GHR deletion (Li-GHRKO), in which we restored IGF-1 production via hepatic IGF-1 transgene (HIT), the Li-GHRKO-HIT mouse [28]. In that study we show that normalized serum IGF-1 levels in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice improved systemic dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, but did not resolve NAFLD or hepatic inflammation. NAFLD in the Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT occurs as early as 6 weeks of age, during puberty, when trabecular bone acquisition peaks and cortical bone continues to mineralize. In addition to hepatic inflammation, we found increases in the expression of oxidative stress markers in livers of Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice [28]. Previous studies have linked oxidative stress with impaired bone remodeling and low bone mass [39–42]. Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) impairs osteoblasts activity and enhances osteoclast bone resorption [43, 44]. We hypothesized that liver GHR mediates skeletal acquisition and maintenance not only through systemic IGF-1, but also via other GH-regulated liver-derived factors and oxidative stress regulators that are impacted by liver disease. To address our hypothesis we followed bone microarchitecture as well as systemic factors regulating bone health, at 16 (peak bone acquisition), 52 (mature adulthood) and 104 (aging) weeks of age in four groups of male mice control, Li-GHRKO, Li-GHRKO-HIT and HIT. We found that restoration of systemic IGF-1 in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice improved their peak bone mass acquisition and restored cortical bone morphology as well as mechanical properties that sustained these determinants through aging. However, the early onset and persistence of NAFLD, and hepatic inflammation in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice impaired their liver function and the capability to produce IGF-1 through aging, leading to persistent deterioration of trabecular bone microarchitecture that associated with increased ROS and impaired mitochondrial respiration in primary osteoblast cultures. Overall, our study suggests that reductions in hepatic IGF-1 production due to liver disease are the major cause for cortical bone impairment and reduced areal BMD.

METHODS

Animals

The generations of hepatic igf-1 transgenic (HIT) mice [45] and the floxed ghr mice [46] were previously described. Gene inactivation of the ghr in liver was achieved by the cre/lox-P system, as described by us previously [47]. All mice were in the C57BL/6J (B6) genetic background. Weaned mice were allocated randomly into cages separated according to their sex. Mice were housed 2–5 animals per cage in a facility with 12-h light:dark cycles and free access to food and water. The different analyses were performed in male mice at the indicated ages.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the NYU School of Medicine (assurance number A3435-01, USDA licensed No. 465), and conform to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines)

Serum hormone levels

Serum/plasma were collected via orbital bleeding immediately after euthanasia with CO2 between 8 and 10 AM. Hormones were measured by ELISA; IGF-1 (ALPCO, Cat# 22-IG1MS-E01), PTH (Immunotopics, Cat# 60-2305), osteocalcin (Immutopics, Cat# 60-1305), CTX (MyBioSource, Cat# MBS703094), OPG (R&D Systems, Cat# MOP00), OPN (R&D Systems, Cat# MOST00), and cytokines (Meso Scale Discovery, Cat# K152A0H-1).

Gene expression

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or by RNeasy Plus kit (Cat# 74134, Qiagen), reverse-transcribed to cDNA (Cat# 18080-051, Life technologies), and subjected to real-time PCR using SYBR master mix (Life Technologies/Applied Biosystems, NY, USA Cat#4385612) on a BioRad CFX384™ real-time machine. Transcript levels were assayed three times in each sample, and corrected to 18S RNA. The primer sequences as follows: F4/80 forward 5′-GAAGGCTCCCAAGGATATGGA-3′ reverse 5′-TGCTTGGCATTGCTGTATCTG-3′; MCP-1 forward 5′-CTTCTGGGCCTGCTGTTCA-3′ reverse 5′-GAGTAGCAGCAGGTGAGTGGG-3′; IL6 forward 5′-TCTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCC-3′ reverse 5′-TTAGCCACTCCTTCTGTGAC-3′; TNFα forward 5′-TTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGGGGTGATCG-3′ reverse 5′-GTATGAGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGTG-3′; OPN forward 5′-TGCACCCAGATCCTATAGCC-3′ reverse 5′-CTCCATCGTCATCATCATCG-3′; OPG forward 5′-AGTCCGTGAAGCAGGAGT-3′ reverse 5′-CCATCTGGACATTTTTTGCAAA-3′; Ap2 forward 5′-AGGAAGGTGAAGAGCATCATA-3′ reverse 5′-CATAACACATTCCACCACCAG-3′; PPARg forward 5′-TTCCGAAGAACCATCCGATTG-3′ reverse 5′-TGGCATTGTGAGACATCCCCAC-3′; Fetuin A forward 5′-TTGCTCAGCTCTGGGGCT-3′ reverse 5′-GGCAAGTGGTCTCCAGTGTG-3′.

Micro-CT: Micro-computed tomography (CT)

Micro-CT was performed according to published guidelines [48]. The left femora were scanned using a high-resolution SkyScan micro-CT system (SkyScan 1172, Kontich, Belgium). Images were acquired using a 10 MP digital detector, 10W energy (100kV and 100 μA), and a 0.5 mm aluminum filter with a 9.7μm image voxel size. A fixed global threshold method was used based on the manufacturer’s recommendations and preliminary studies, which showed that mineral variation between groups was not high enough to warrant adaptive thresholds. The cortical region of interest was selected as the 2.0 mm mid-diaphyseal region directly below the third trochanter, which includes the mid-diaphysis and more proximal cortical regions. The trabecular measurements were taken at the femur distal metaphysis 2.5 mm below the growth plate.

Histomorphometry

Histomorphometry was performed according to published guidelines [49]. Sixteen-week-old animals were injected intraperitoneally twice with calcein (10 mg/kg) 8 or 10 and 2 days before sacrifice. The femora were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), and sectioned (80 μm thickness) at the mid-diaphysis using a low-speed diamond-coated wafering saw (Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA). The sections were adhered to either glass or acrylic slides using non-fluorescing mounting medium. The final section thicknesses after polishing were 30–40 μm. All measurements were performed using an OsteoMeasure system (Osteometrics, Atlanta, GA, USA) in accordance with standard protocols. Sections were imaged using a digital camera attached to a visible light/fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan2, Zeiss AxioVision, Thornwood, NY, USA).

Histology

Livers were fixed in 10% zinc formalin, processed for paraffin sectioning (5-μm sections) and stained with F4/80 (abcam, Cat# ab6640, 1:100) and Iba1 (ThermoFisher, Cat# PA5-27436, 1:100). Femora were fixed in 10% zinc formalin and decalcified using 10% EDTA. Decalcified bones were then processed for paraffin sectioning (5-μm sections) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tibiae sections from 52 weeks old mice were stained with anti-8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine (abcam, Cat#ab10802, 1:200). Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining of bone sections was done using a kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma 387A). Number of osteoclasts on trabecular bone surface was counted manually.

3-point bending assay

Harvested femurs were stored frozen at −20C and wrapped in PBS-soaked gauze. At testing time, samples were brought to room temperature in a saline bath. Three-point bending tests to failure were carried out using a BOSE materials testing machine (Electroforce, 3220, MN). The upper loading span width was 3.0mm and the lower support span width was 6.0 mm. Femora were positioned in a saline bath posterior side down on the supports in order to generate bending moments about the medial-lateral axis. Samples were carefully centered on the supports to ensure maximum load at the midpoint of the diaphysis. A preload of 1 N was briefly applied to secure the sample, and then a ramp waveform at a constant displacement rate of 0.10 mm/s was applied until failure. Load-displacement curves were recorded and subsequently analyzed.

Western immunoblotting

Liver proteins were extracted in modified CHAPS buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1.25% CHAPS, 2 mM NaF, 10 mM Na-pyrophosphate, 8 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Cat# 04693132001]). Tissue lysates (60–100 μg) were separated using 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE (Life Technologies, Cat# NP0335) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Cat# 170-4158). Proteins were detected using primary antibodies against Iba1 (ThermoFisher, Cat# PA5-27436, 1:100), and F4/80 (abcam, Cat# ab6640, 1:100).

Primary OB OC cultures

Long bones were dissected under sterile conditions. Bone marrow was flushed with 3ml of α-minimal essential medium (αMEM; Invitrogene) and washed three times with αMEM. For primary osteoblast cultures 3×106cells were seeded in 3 wells of 6-well plate for 4 days in αMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and subsequently for 3 weeks in osteoblast differentiation media (αMEM, 10%FCS, 10−8M dexamethasone, 8mM beta-glycerol phosphate, and 50ug/ml ascorbic acid). After 21 days cultures were stained for Alk-Phos (Sigma 86). For primary osteoclast cultures, bone marrow cells were seeded in αMEM supplemented with 10%FCS over night, non-adherent cells were collected, separated on ficoll gradient, and the myeloid cell layer was collected and washed 2 times with αMEM. Cells (0.15X106) were seeded in 96-well plate in the presence of 40ng/ml M-CSF (PEPROTECH, 315-02) and 60 ng/ml RANKL (R&D systems, 462-TEC/CF) for 5–7 days and then subjected to TRAP staining using a kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma 387A).

Cellular content of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Cells were seeded (0.4X106 cells/ml) on collagen-coated black-walls 96 well plate in growth medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, 41061029) and incubated for 30 min with 10μg/ml DCFDA (ThermoFisher Scientific, D399). ROS levels were determined after 30 min at excitation 485 and emission 535nm (plate reader; Spectra Max5 M5, Molecular devices with Softmax Pro software).

NADH auto-fluorescence

Cells were seeded (0.4X106 cells/ml) on collagen coated glass discs (Fisher Scientific, 12-545-102) in assay medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, 41061029) and visualized by 2000E Nikon Microscope Eclipse TE at 20X magnification at excitation 351nm and emission at 375–470nm. NADH redox index calculations were done as follows; basal level (taken for 1–2 min) relative to maximal respiration after 1 μM FCCP (0%) taken for 1–2 min, and minimal respiration after 1 mM NaCN (100%) taken for 1–2 min.

Mitochondrial stress assay

Primary osteocytes (0.4X106 cells/ml, a pool of 2–3 mice per group) were seeded on a collagen-coated plate (Agilent, 102340-100) in triplicates. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was determined using the cellular respiration analyzer (Seahorse Analyzer, Agilent Technologies) at basal, upon oligomycin (1 μM), FCCP (2 μM), and Rotenone/antimycin (0.5 μM) additions. Data was normalized to cell number determined at the end of the assay, and analyzed using the Wave software. Assays were repeated a few times using osteocyte preparations from several mice per group. Data from several assays were combined after normalization of basal OCR to 100%.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were tested using ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, significance accepted at p < 0.05. Blinding: Scientists were blinded to sample IDs in all experimental procedures.

RESULTS

Chronic hepatic inflammation and steatosis impair liver expression of the IGF-1 transgene

Body weight was followed from 16 to 104 weeks of age (Fig 1A). As shown previously [28], mice of all groups had similar body weight through 52 weeks of age. Li-GHRKO mice started to loose weight at 52 weeks, and by 104 weeks their body weight reduced significantly when compared to controls. Declines in body weights in Li-GHRKO mice were mainly attributed to reductions in fat mass (Fig 1B, Sup. table 1). Li-GHRKO mice show a two-fold increase in body adiposity through 52 weeks of age (Fig 1B). By 104 weeks, Li-GHRKO mice show a 50% decrease in body adiposity, and their relative gonadal fat pad’s weight is lower than controls. In contrast, control mice show increased body adiposity with age, while Li-GHRKO-HIT mice show relatively no change in body adiposity through 104 weeks of age. Li-GHRKO mice did not show significant increases in subcutaneous fat pads, but during aging lost weight from these pads (Fig 1C, Sup. table 1).

Figure 1. Hepatic IGF-1 does not resolve inflammation in mice with liver-specific GHR ablation.

A) Body weights of male mice were followed to 104 weeks of age (sample size per each genotype/age indicated in supplement table 1). B) Relative weights of gonadal fat pads and C) posterior subcutaneous fat pads in male mice were obtained from sub groups sacrificed at the indicated ages. D) Immunohistochemical analyses of 5um liver sections from male mice at 52 weeks using the F4/80 (macrophage marker) and Iba1 (inflammatory marker) antibodies. E) Western immunoblotting of liver protein extracts from male mice at 52 weeks detecting F4/80 and Iba1 protein levels (N=6 per group). F) Serum IGF-1 levels in male mice sacrificed at the indicated ages (N>8 per group per age). Data presented as mean ± SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Steatosis was not resolved when IGF-1 levels were normalized in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice [28] and persisted to 104 weeks (Sup. table 2). We have previously described that both groups (Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT) show hepatic inflammation at 16–24 weeks of age. Here we show that hepatic inflammation persisted to 104 weeks and even worsened in both groups. Liver gene expression of the inflammatory markers interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL6, IL18, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), MyD88, and the macrophage marker F4/80, increased with age and were higher in Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT when compared to controls (Sup. fig 1). Immunohistochemical analyses showed increase in F4/80 and Iba-1 (a marker of inflammation) positive cells in 52 weeks old mice (Fig 1D). At 52 weeks we found significantly more immune cell infiltrates in Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Sup. table 2). Liver protein extracts from 52 weeks old mice showed high levels of F4/80 and Iba1 in Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Fig 1E).

The poor health conditions in the aged Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice associated with reduced IGF-1 production. We have previously showed that serum IGF-1 levels in the Li-GHRKO mice reduced by ~95%, while expression of the hepatic igf-1 transgene (HIT) normalized serum IGF-1 levels in the Li-GHRKO-HIT [28] up to ~30 weeks of age. However, with age liver conditions of the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice worsened. We found increased inflammatory cell infiltrates and micro-metastases as well as extra-hepatic tumors (Sup Table 2) that likely contributed to marked reductions in liver production of IGF-1 in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Fig 1F).

Hepatic IGF-1 transgene restored cortical bone traits and mechanical properties in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice during growth

To address whether normalization of serum IGF-1 was sufficient to rescue skeletal properties in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice despite their liver disease, we assessed femur morphology of male mice at 16, 24, 52, and 104 weeks of age. Cortical bone analyses were taken at the femur mid-diaphysis. Femur lengths did not differ between the groups (Fig 2A, Table 1). In sharp contrast, total cross-sectional area at the mid-diaphysis (Tt.Ar) significantly reduced by 10% at 16 weeks of age and by 30% at all other ages in femurs from Li-GHRKO mice (Fig 2B, Table 1). Restoration of hepatic IGF-1 in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice produced femurs with only 6%–10% decreases in Tt.Ar (Fig 2B, Table 1). Likewise, cortical bone area (B.Ar) in Li-GHRKO mice reduced at all ages, and by 104 weeks of age we detected a ~40% decrease in B.Ar. In contrast, B.Ar in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice was normalized and by 52 and 104 weeks of age was similar to controls (Fig 2C, Table 1). Cortical bone thickness (Cs.Th) in Li-GHRKO mice decreased by 15% as compared to controls up to 52 weeks of age and by 30% at 104 weeks (Fig 2D). This data suggest that restoration of serum IGF-1 during growth protects cortical bone acquisition, even in states of liver steatosis. Further, cortical bone properties were maintained through in aging the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, despite reductions in their serum IGF-1 levels (which started at ~52 weeks of age).

Figure 2. Hepatic IGF-1 restores cortical bone morphology and mechanical properties in mice with liver-specific GHR ablation.

A) Femur length in male mice sacrificed at the indicated ages (measured using a digital caliper). Femurs dissected from male mice at the indicated ages, analyzed by micro-CT at 9.7um resolution. B) Total cross-sectional area, C) bone area, D) cortical bone thickness, were determined in a 2mm3 volume at the femur mid diaphysis. E) Correlation between femur total cross-sectional area and body weight in male mice aged 16–104 weeks. F) Correlation between femur robustness (total cross-sectional area/femur length) and body weight in male mice aged 16–104 weeks. Mechanical properties G) strength, H) toughness, and I) stiffness, tested by 3-point bending assay of femurs dissected from male mice at the indicated ages. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Sample size per each genotype/age indicated in table 1. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Table 1.

Skeletal traits measured by mCT, 3-point bending, and histomorphometry of femurs dissected from 16, 52, and 104 weeks old mice.

| Age | Trait | Control | HIT | Li-GHRKO | Li-GHRKO-HIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 weeks | Cortical bone (femur, mid-diaphysis) | ||||

| Sample size | 19 | 9 | 14 | 13 | |

| Total cross-sectional area, mm2 | 1.905±0059 | 1.949±0.035 | 1.719±0.030 b | 1.813±0.035 | |

| Bone area, mm2 | 0.914±0.018 | 0.918±0.018 | 0.722±0.013 ab | 0.830±0.014 abc | |

| Cortical bone thickness, mm | 0.189±0.003 | 0.193±0.003 | 0.159±0.002 ab | 0.182±0.003 abc | |

| Polar moment of inertia, 1/mm4 | 0.449±0.017 | 0.466±0.016 | 0.325±0.011 ab | 0.385±0.013 ab | |

| Marrow area, mm2 | 0.696±0.065 | 1.031±0.022 a | 0.997±0.020 a | 0.983±0.028 a | |

| Trabecular bone (femur, distal metaphysis) | |||||

| Bone volume/total volume, % | 14.696±0.850 | 8.243±0.356 a | 11.483±0.833 | 7.521±0.710 abc | |

| Trabecular thickness, mm | 0.054±0.001 | 0.048±0.001 a | 0.046±0.002 a | 0.045±0.002 a | |

| Trabecular number, 1/mm | 2.712±0.133 | 1.720±0.060 a | 2.460±0.115 | 1.651±0.131 abc | |

| Trabecular spacing, mm | 0.197±0.005 | 0.228±0.004 | 0.207±0.003 | 0.236±0.006 abc | |

| Bone mineral density mg/cc | 0.347±0.023 | 0.284±0.006 a | 0.329±0.023 | 0.285±0.010 a | |

| Mechanical properties (3-point bending assay) | |||||

| Sample size | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Strength (max force), N | 11.425±0.285 | 12.356±0.948 | 8.867±0.122 ab | 13.462±0.400 c | |

| Toughness (work to fracture), N/mm•107 | 232±9.03 | 236±26.4 | 280±26.5 | 273±19.7 | |

| Stiffness, N/mm•105 | 6.17±0.56 | 5.06±0.29 | 4.76±0.39 | 5.61±0.19 | |

| Histomorphometry (cortical bone) | |||||

| Sample size | 11 | 10 | 9 | 7 | |

| Endosteal surface; MS/BS | 1.195±0.176 | 1.399±0.206 | 1.173±0.145 | 1.095±0.138 | |

| Endosteal surface; MAR | 1.028±0.172 | 1.116±0.069 | 0.738±0.145 | 1.063±0.100 | |

| Endosteal surface; BFR | 1.034±0.145 | 1.612±0.308 | 0.774±0.136 b | 1.159±0.184 | |

| Periosteal surface; MS/BS | 0.911±0.104 | 1.031±0.153 | 0.772±0.140 | 0.765±0.137 | |

| Periosteal surface; MAR | 1.169±0.138 | 0.769±0.244 | 0.568±0.114 a | 0.745±0.171 | |

| Periosteal surface; BFR | 1.062±0.184 | 0.875±0.277 | 0.436±0.109 | 0.687±0.231 | |

| 52 weeks | Cortical bone (femur, mid-diaphysis) | ||||

| Sample size | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | |

| Total cross-sectional area, mm2 | 2.515±0.033 | 2.316±0.085 | 2.008±0.058 a | 2.402±0.097 c | |

| Bone area, mm2 | 1.064±0.021 | 1.018±0.024 | 0.823±0.033 ab | 1.078±0.047 c | |

| Cortical bone thickness, mm | 0.186±0.004 | 0.194±0.003 | 0.165±0.004 ab | 0.194±0.006 c | |

| Polar moment of inertia, 1/mm4 | 0.699±0.018 | 0.615±0.033 | 0.427±0.027 ab | 0.673±0.055 c | |

| Marrow area, mm2 | 1.451±0.037 | 1.298±0.071 | 1.185±0.035 a | 1.324±0.060 | |

| Trabecular bone (femur, distal metaphysis) | |||||

| Bone volume/total volume, % | 9.822±0.807 | 5.830±0.924 a | 5.405±0565 a | 7.023±0.617 a | |

| Trabecular thickness, mm | 0.055±0.002 | 0.066±0.002 a | 0.043±0.001 ab | 0.057±0.002 c | |

| Trabecular number, 1/mm | 1.787±0.148 | 0.878±0.131 a | 1.250±0.108 | 1.253±0.116 | |

| Trabecular spacing, mm | 0.310±0.010 | 0.368±0.009 a | 0.295±0.010 b | 0.308±0.016 b | |

| Bone mineral density mg/cc | 0.287±0.021 | 0.201±0.016 a | 0.220±0.013 | 0.260±0.011 b | |

| Mechanical properties (3-point bending assay) | |||||

| Sample size | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Strength (max force), N | 11.902±0.376 | 13.223±0.640 | 6.317±0.610 ab | 12.631±1.078 c | |

| Toughness (work to fracture), N/mm •107 | 139±18.7 | 207±14.2 a | 72.6±7.6 ab | 160±12.2 c | |

| Stiffness, N/mm•105 | 5.74±0.39 | 7.47±0.72 | 5.60±0.57 | 6.12±0.17 | |

| 104 weeks | Cortical bone (femur, mid-diaphysis) | ||||

| Sample size | 19 | 4 | 12 | 5 | |

| Total cross-sectional area, mm2 | 2.826±0.054 | 3.07±0.194 a | 2.096±0.060 ab | 2.539±0.021 c | |

| Bone area, mm2 | 1.088±0.035 | 1.099±0.117 | 0.632±0.036 ab | 1.103±0.033 c | |

| Cortical bone thickness, mm | 0.164±0.008 | 0.166±0.017 | 0.116±0.008 | 0.190±0.010 c | |

| Polar moment of inertia, 1/mm4 | 0.804±0.032 | 0.917±0.136 | 0.375±0.025 b | 0.728±0.019 | |

| Marrow area, mm2 | 1.738±0.047 | 1.972±0.099 a | 1.465±0.057 b | 1.436±0.035 b | |

| Trabecular bone (femur, distal metaphysis) | |||||

| Bone volume/total volume, % | 5.719±0.946 | 2.529±1.111 | 4.495±0.909 | 2.855±0.789 | |

| Trabecular thickness, mm | 0.055±0.003 | 0.066±0.004 | 0.049±0.002 | 0.040±0.010 | |

| Trabecular number, 1/mm | 0.833±0.153 | 0.637±0.122 | 0.853±0.147 | 0.514±0.144 | |

| Trabecular spacing, mm | 0.650±0.132 | 0.406±0.191 | 0.406±0.035 | 0.303±0.050 | |

| Bone mineral density mg/cc | 0.191±0.025 | 0.168±0.024 | 0.183±0.021 | 0.144±0.038 | |

| Mechanical properties (3-point bending assay) | |||||

| Sample size | 17 | 4 | 9 | 5 | |

| Strength (max force), N | 15.242±1.402 | 14.932±1.902 | 6.298±1.687 ab | 13.282±1.234 c | |

| Toughness (work to fracture), N/mm•107 | 227±21.8 | 176±14.3 | 103±38.3 | 184±17.2 | |

| Stiffness, N/mm•105 | 5.44±0.36 | 5.80±0.10 | 4.19±0.75 | 5.09±0.23 | |

Data presented as mean±SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05,

- as compared to control,

- as compared to HIT,

- as compared to Li-GHRKO.

As was previously established [50], there are strong relationship between body weight and skeletal parameters. Accordingly, Tt.Ar increases proportionally to increases in body weight. Indeed, in control, HIT and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice we found linear relations between Tt.Ar and body weight with r2=0.64, r2=0.77, r2=0.80, respectively (p<0.05) (Fig 2E). Conversely, the Li-GHRKO did not adapt their bones to increasing body weight (r2=0.22) (Fig 2E). Similarly, bone robustness, calculated as the ratio Tt.Ar/length, and measures the amount of lateral growth (expansion) relative to longitudinal growth, shows linear relationships with body weight. We found that in control, HIT, and Li-GHRKO-HIT mice bone robustness relates directly to body weight with r2=0.61, r2=0.74, r2=0.76, respectively, (p<0.05) (Fig 2F). Li-GHRKO mice, on the other hand, show no relationship between bone robustness and body weight (r2=0.07) (Fig 2F). These data suggest impaired bone adaptation in the Li-GHRKO mice where periosteal bone apposition is compromised. Indeed, we found that periosteal mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) of 16 weeks old mice significantly decreased in the Li-GHRKO mice when compared to controls (Table 1). This data suggest that restoration of serum IGF-1 during growth preserve bone adaptation to mechanical loads (body weight), even in states of liver steatosis.

Mechanical properties were assessed by 3-point bending assays in femurs from male mice at 16, 52, and 104 weeks of age (Table 1). Consistent with the morphological findings by mCT, we found that femur strength in Li-GHRKO mice was compromised at all ages with progressive declines in strength (max force) (Fig 2G). In contrast, Li-GHRKO-HIT femurs showed similar bone strength (Fig 2G), toughness (Fig 2H), and stiffness (Fig 2I) to controls. These data strengthen our previous observation regarding bone adaptation to increased loads, and show again that restoration of serum IGF-1 during growth preserves bone mechanical properties, and these are maintained even in states of liver steatosis.

Overall, morphological and mechanical properties of femurs were normalized with restoration of serum IGF-1 indicating that abnormalities in cortical bone in face of liver disease (NAFLD) can be corrected by IGF-1 during growth and maintained through aging, even when IGF-1 levels are reduced later on, as seen in the case of Li-GHRKO-HIT mice.

Hepatic IGF-1 transgene was insufficient for restoration of trabecular bone properties in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice

While hepatic IGF-1 restored the morphology and mechanical properties of cortical bone in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, it did not improve the morphology of the trabecular bone compartment. We found that despite restoration of serum IGF-1 levels trabecular bone fraction (bone volume/total volume, BV/TV%) reduced by 50% in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice as compared to controls starting at 16 weeks of age (Fig 3A, Table 1). Subsequently, trabecular BMD reduced by ~20% in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice as compared to controls at almost all ages studied (Fig 3B, Table 1). Reductions in BV/TV and BMD in the Li-GHRKO-HIT related to reduced trabecular number (Fig 3C, Table 1), but not trabecular thickness (Table 1). This suggests that trabecular bone gaining during growth, and/or increased bone resorption, was impaired in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. Histological evaluation of trabecular bone at the distal femur of 16 and 52 week-old mice revealed a 50% reduction in bone surface in HIT mice (from 3745±393um at 16W to 1904±466um at 52W), and ~30% reductions in Li-GHRKO (from 3036±412um at 16W to 2132±232um at 52W) and the Li-GHRKO-HIT groups (from 4186±627um at 16W to 2854±1885um at 52W), while controls showed only 6% decrease (from 3784±455um at 16W to 3566±1009um at 52W) in trabecular bone surface. Nonetheless, osteoclast (OC) number/bone surface did not differ between the groups at 16 (control 6.5±1.5 OC/mm; HIT 5.5±0.7 OC/mm; Li-GHRKO 7.6±1.0 OC/mm; Li-GHRKO-HIT 7.5±1.7 OC/mm) or 52 weeks of age (control 6.3±1.4 OC/mm; HIT 10.5±1.4 OC/mm; Li-GHRKO 8.6±4.4 OC/mm; Li-GHRKO-HIT 7.2±2.8 OC/mm). We then measured circulating levels of the bone turnover markers osteocalcin (secreted by osteoblasts bone forming cells), carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks (CTX, a marker of bone resorption), and parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is elevated with age and known to increase bone resorption [51]. Serum osteocalcin levels decreased with age, but did not differ significantly between the groups (Fig 3D) indicating reduced osteoblast activity. In agreement with the aforementioned histology data showing only 6% reductions in trabecular bone surface in control mice, their serum CTX levels reduced during aging, reflecting low bone turnover (Fig 3E). Li-GHRKO-HIT mice showed reduced CTX levels at 16 weeks that were elevated at 104 weeks of age and may relate to the drops in IGF-1 (Fig 3E). Serum PTH levels increased in control and HIT mice at 104 weeks, while in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice serum PTH raised earlier at 52 weeks and remained high at 104 weeks of age, possibly reflecting increases in bone remodeling in that group (Fig 3F).

Figure 3. Hepatic IGF-1 does not restore trabecular bone volume and mineral density in mice with liver-specific GHR ablation.

Femurs dissected from male mice at the indicated ages, analyzed by micro-CT at 9.7um resolution. A) Trabecular bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), B) trabecular BMD, C) trabecular number, were determined in a 2mm3 volume at the femur distal metaphysis at the indicated ages. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Sample size per each genotype/age indicated in table 1. Serum levels of D) osteocalcin, E) CTX, F) PTH were determined in samples obtained from male mice at the indicated ages using ELISA. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Hepatic steatosis and inflammation associate with increase osteoblast cell stress

To better understand the reasons for reduced trabecular bone volume in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice we assessed the number of osteoblast and osteoclast progenitors in the bone marrow. Primary osteoblast and osteoclast cultures from bone marrow of 24 weeks old mice did not show significant differences in the number of alkaline phosphatase (alk-phos) positive colonies (p=0.08) or osteoclast number (p=0.85) (Fig 4A). Cultures established from 52 weeks old Li-GHRKO mice showed ~3-fold increase in osteoclast progenitors in Li-GHRKO mice and ~5–6-fold in Li-GHRKO-HIT and HIT cultures (p=0.001) (Fig 4A). Likewise, we found ~10-fold increase in alk-phos positive colonies in osteoblast cultures from Li-GHRKO mice, while Li-GHRKO-HIT and HIT cultures showed ~5-fold increase in alk-phos staining (p<0.001) (Fig 4A). Overall the in vitro data suggests increases in both osteoblast and osteoclast progenitors in the Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice at 52 weeks of age.

Figure 4. Liver disease associates with increased osteoblast cell stress.

A) Primary osteoblast (OB) and osteoclast (OC) cultures established from bone-marrow stem cells (MSCs) dissected from male mice at the indicated ages. OB colonies were stained using Alk-Phos staining kit (N=5 per group per age). Primary OC were established from non-adherent cells separated on ficoll gradient and plated in 96-well plate in the presence of 40ng/ml M-CSF and 60 ng/ml RANKL. OC were stained using TRAP kit (N=5 per group per age). B) Basal ROS levels in osteoblast cultures from control (n=8), HIT (n=6), Li-GHRKO (n=9), and Li-GHRKO-HIT (n=9) mice. C,D) NADH redox index in osteoblast cultures from control (n=11), HIT (n=6), Li-GHRKO (n=12), and Li-GHRKO-HIT (n=7) mice. E,F) Mitochondrial stress resistance measured by the Seahorse analyzer in control (n=11), HIT (n=6), Li-GHRKO (n=12), and Li-GHRKO-HIT (n=7) mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Next, we evaluated the expression of oxidative stress markers in the bone marrow from 16 and 104 weeks old mice (Sup. Fig 2A). We found significant elevations in the expression of catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in bone marrow from the Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. This data was in agreement with increased staining of tibiae sections with 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (a marker of oxidative stress) on trabecular bone surface of Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT bones (Sup. Fig 2B). Further, evaluation of differentiated osteoblast cultures (21 days) revealed significant increases in basal reactive oxygen species (ROS) in both Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT cultures (Fig 4B), suggesting that redox homeostasis and potentially mitochondrial function in those cultures are impaired. We next measured the redox state of the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH pair in osteoblast cultures, but no differences were found between the groups (Fig 4C,D). However, the use of a mitochondrial stress assay in osteoblasts cultures revealed decreased maximal respiration upon addition of the membrane uncoupler carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (Fig 4EF), suggesting an impaired mitochondrial function in osteoblasts from Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. It is conceivable that the impaired mitochondrial function affects osteoblast activity and may partially explain the reduced trabecular bone gains or non-balanced resorption in Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice during growth and aging, respectively.

Gene expression studies of bone marrow RNA isolated from 16 weeks old mice revealed an increase in the expression of ap2 and ppar-γ genes in the Li-GHRKO mice, indicating increased marrow adiposity (Sup. fig 2C). However, this was normalized in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. Expression of TNFα (p=0.017) increased in Li-GHRKO but normalized in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Sup. fig 2C). Likewise, osteopontin increased by 25 fold (p=0.0007) in bone marrow of 16 weeks old Li-GHRKO but normalized in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Sup. fig 2C). At 104 weeks, fat and inflammatory markers increased in the bone marrow of both Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT mice (Sup. fig 2D), suggesting that during growth (up to 16 weeks) serum IGF-1 was sufficient to reduce adiposity and inflammation in the bone marrow of Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, while during aging when serum IGF-1 declined due to enhanced liver disease, bone marrow adiposity and inflammation worsened.

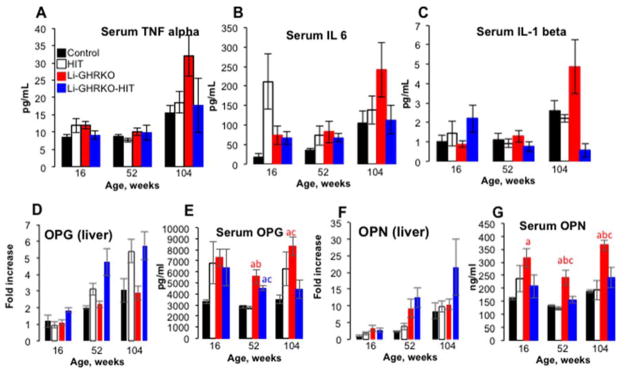

Contribution of inflammatory cytokines, osteoprotegrin, and osteopontin to osteodystrophy associated with liver disease

There are several liver-derived candidate proteins including cytokines and mineral regulating proteins that may contribute to decreased trabecular bone fraction in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. Serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin 6 (IL6), and IL1-β were elevated with aging in all groups but were significantly higher in serum of the Li-GHRKO mice (Fig 5A–C). Serum cytokines levels in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice were similar to that of controls at most ages, and thus unlikely to be major contributors to the reduced trabecular bone in these mice.

Figure 5. Hepatic IGF-1 does not improve systemic inflammation in mice with liver-specific GHR ablation.

A) TNFa, B) IL6, and C) IL-1b were determined in samples obtained from male mice at the indicated ages using ELISA. D) OPG gene expression in liver (N>8 per group per age). E) Serum OPG levels determined by ELISA (N>8 per group per age). F) OPN gene expression in livers from male mice at the indicated ages (N=6 per group per age). G) Serum OPN levels determined by ELISA (N>8 per group per age). Data presented as mean ± SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Liver expression of osteoprotegrin (OPG), a decoy receptor for the receptor activator for nuclear factor k-B ligand (RANKL), which is highly expressed in the mouse liver [52], significantly increased in all groups with age (Fig 5D) and was highest in the Li-GHRKO-HIT livers. However, serum levels of OPG increased significantly in both Li-GHRKO and Li-GHRKO-HIT at 16 and 52 weeks of age as compared to controls (Fig 5E). Expression of osteopontin (OPN), a member of the small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLING) family, significantly increased in all groups with age (Fig 5F). However, OPN levels in serum were significantly higher in Li-GHRKO mice (Fig 5G), while Li-GHRKO-HIT mice show reduced OPN in serum. Together, these data suggest that systemic cytokines or liver-derived OPG and OPN, are not major contributors to decreased trabecular bone in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice.

DISCUSSION

Interactions between the hepatic and osseous systems are complex. Several studies have shown that impairments of the hepatic somatotropic axis (GH/IGF-1) are not confined to NAFLD [1, 3, 4, 25], but also appear in patients with chronic viral hepatitis [7], liver cirrhosis [8–12], and chronic cholestatic liver disease [13, 14], which all show decreases in serum IGF-1 and low BMD. Further, in children with end-stage liver disease and low serum IGF-1, liver transplantation resulted in normalization of IGF-1 levels followed by a full recovery of BMD within 12 months after transplantation [53]. These data suggest that GHR action in the liver and liver-derived IGF-1 play an increasingly prominent role in the pathogenesis of low BMD in patients with chronic liver diseases and those with advancing liver failure awaiting transplantation.

In this study, we addressed whether disruptions in the somatotropic axis are the major cause for reduced BMD seen in states of chronic liver disease. We used a mouse model of hepatocyte-specific GHR gene ablation (Li-GHRKO), which shows chronic hepatic steatosis, local inflammation, and reduced BMD. Using a crossing strategy we restored liver production of IGF-1 in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. Of importance although the Li-GHRKO-HIT is not a disease model, it allowed us to dissect the roles of liver-derived IGF-1 in the pathogenesis of osteodystrophy during liver disease. We found that hepatic IGF-1 restored cortical bone acquisition, microarchitecture, and mechanical properties during growth in Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, which was maintained through aging. In contrast, trabecular bone volume was not restored in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice even during growth.

Studies in humans have tested whether impaired bone formation accounts for the reduced BMD in hepatic-osteodystrophy. Several have reported inverse relationships between serum osteocalcin (an osteoblast-derived peptide) and NAFLD [54–57], while others have not found a consistent relationship [58–60]. In a study of 80 patients with various types of chronic liver disease and 40 healthy controls the authors found that the mean trabecular bone volume and trabecular thickness were significantly reduced in both men and women with chronic liver disease. This was associated with decreased bone-formation and bone-turnover rates, and reduced osteoblastic surfaces that could contribute to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis in those patients [61]. We found age-dependent decreases in serum osteocalcin in all mouse groups, independent of hepatic lipid content (i.e. NAFLD). Bone formation indices measured at the femur mid-diaphysis of 16 weeks old mice, were similar between controls and Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, supporting our mCT data that show restoration of cortical bone parameters. Another possible contributor to reduced bone formation is increased bone marrow adiposity, which is thought to inhibit osteoblast differentiation and enhance osteoclast differentiation [62]. A recent study with 125 patients showed that bone marrow fat content was positively associated with hepatic fat content in children with known or suspected NAFLD [24]. We assessed an index of bone marrow adiposity using gene expression of ap2 and ppar-g, markers of mature adipocytes. We found that Li-GHRKO mice have elevated expression of ap2 and ppar-g at 16 weeks that persisted to 52 and 104 weeks of age. In Li-GHRKO-HIT mice elevations in ap2 and ppar-g were seen during aging (52–104 weeks of age) at times when serum IGF-1 declined. Thus, while bone marrow adiposity may be associated with reduced trabecular bone mass during aging it cannot fully explain the reduced trabecular BMD seen at 16 weeks of age in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice.

The effects of oxidative stress on osteoblast function are context-dependent. Physiological elevations in ROS were shown to promote osteogenesis via increases in osteoblasts differentiation and matrix mineralization [42, 63, 64]. However, when abnormally elevated, ROS may have detrimental effects leading to decreased osteoblast viability, differentiation, and function [65, 66]. In line with this evidence, the superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) null mice exhibit reductions in BMD in both male and female mice as compared to control littermates [67], suggesting important roles for ROS inactivation in bone cells by SOD1. In our initial characterization of the Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mouse models we found increased oxidative stress markers in liver and serum of the Li-GHRKO that were partially resolved in the young (16–52 week-old) Li-GHRKO-HIT mice [28]. Here we tested whether oxidative stress imposed on the Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT relates to their bone phenotype. Indeed, we found that gene expression of oxidative stress markers in bone marrow from Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice was increased. We then found that primary osteoblasts from the Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT exhibit increased basal ROS production. Increased levels of ROS can lead to cell damage and death [68]. ROS generated by mitochondria have been suggested to contribute to the cell aging process. We have thus looked at mitochondrial function in osteoblasts from our mice. We found decreased maximal cellular respiration capacity and spare capacity in osteoblasts from Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice as compared to controls. Maximal respiration capacity describes the amount of ATP that a cell can produce via oxidative phosphorylation in case of a sudden increase in energy demand (such as increase in workload), and spare capacity reflects the differences in ATP produced via oxidative phosphorylation between basal and maximal respiration. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation (insufficient ATP) can drive cells into senescence or apoptosis. Our studies do not show a direct link between osteoblasts mitochondrial function and the bone phenotype. However, together with the reduced trabecular bone volume in both Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice, these in vitro studies possibly reflect impaired osteoblast function in these mice.

Increased bone resorption markers were seen in several studies of patients with chronic liver disease [69, 70]. In our study we show that serum CTX, a marker of bone resorption was elevated only at 104 weeks in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. We found increased number of osteoclast progenitors in vitro, but osteoclast number on trabecular bone surfaces at the distal metaphysis of 16 or 52 week-old GHRKO-HIT mice did not differ significantly from controls. Enhanced bone resorption in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice may also be triggered by elevations in PTH (hyperparathyroidism) that stimulate bone remodeling [51]. There are conflicting data from clinical studies of patients with chronic liver disease regarding serum PTH levels and BMD. We found significant increases in serum PTH levels in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice at 52 weeks of age (when serum IGF-1 declined), which possibly contributed to the reduced trabecular bone volume in these mice. Elevations in systemic, liver-derived inflammatory cytokines were also shown to correlate with increased bone resorption markers in human [71–74] and animal models [75–78]. However, there are several studies showing that circulating cytokine levels fail to predict the severity of the bone disease [79, 80] even in children [81]. We did not find differences in systemic inflammation in our models, although the Li-GHRKO mice showed elevations in IL6, IL1β, and TNFα in serum during aging. The involvement of OPG/RANKL in enhanced bone resorption in patients with chronic liver disease was also considered. However, elevations in the OPG/RANKL system may be related to the inflammatory status of the patients [11] and may not directly lead to changes in BMD [82]. Finally, OPN (bone sialoprotein), a GHR negatively-regulated protein, was strikingly increased in patients with liver disease [83] and obesity-induced liver steatosis [84]. In fact, OPN was identified in three independent genome-wide association studies as a predictor of BMD [85–87]. In human, increased OPN levels were associate with osteoporosis [88], while OPN null mice show increased trabecular bone volume [89]. We found increased liver expression of OPN in both Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice. However, while both Li-GHRKO and the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice showed reduced trabecular bone volume, only in Li-GHRKO showed elevated OPN levels in serum, excluding this factor as a major contributor to reduced BMD in the Li-GHRKO-HIT mice.

In summary, we utilized a unique mouse model to test the hypothesis that IGF-I is a major determinant of hepatic osteodystrophy. We showed that reduction in serum IGF-1 associated with chronic liver disease is the main contributor to reduced bone acquisition during growth. Our in vitro data with primary osteoblast cultures revealed increases in basal ROS levels and impaired mitochondrial stress resistance potentially providing a mechanism for the low trabecular bone mass in states of liver disease. Hence the pathogenesis of hepatic osteodystrophy and, in particular, the involvement of the GH/IGF-1 axis in the etiology of the disease, is very complex and compartment specific.

Supplementary Material

Gene expression in livers dissected from male mice at the indicated ages (N>6 per group per age). Data presented as mean ± SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Gene expression of A) oxidative stress markers in bone marrow flushed from male femurs at 16 and 104 weeks of age. B) Paraffin bone sections (5u) from tibiae of 52 weeks old mice stained with 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine, a marker of oxidative stress. C) Gene expression of inflammatory markers in bone marrow of 16, and D) 104 weeks old mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n=4 to 5 mice per group. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Financial support received from National Institutes of Health Grant DK100246 to SY, and Bi-national Science Foundation Grant 2013282 to SY and HW, S10OD010751-01A1 instrument (micro-CT) grant to NYUCD, AR041210 and AR057139 to MBS.

Abbreviations

- GH

Growth hormone

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- GHR

GH receptor

- HIT

hepatic IGF-1 transgene

- JAK2

Janus kinase-2

- STAT5

signal transducer and activator of transcription 5

- IGF-1R

IGF-1 receptor

- BMD

bone mineral density

- IL-1

interleukin 1

- IL6, IL18

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-a

- TRAP

Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase

- CTX

carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- OPG

osteoprotegrin

- RANKL

receptor activator for nuclear factor k-B ligand

- OPN

osteopontin

- SIBLING family

small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins

- MAR

mineral apposition rate

- BFR

bone formation rate

- Tt.Ar

total cross-sectional area

- B.Ar

cortical bone area

- Cs.Th

cortical bone thickness

Footnotes

Disclosure:

All authors concur with the submission. The material submitted for publication has not been previously reported and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. Dr. Yakar is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

COI: None of the authors have COI.

Author contribution:

Zhongbo Liu, Ph.D.: performed all assays, summarized the data and tested for significance.

Tiazhen Han, M.Sc: performed mCT analyses and 3-point bending assays.

Haim Werner, Ph.D.: participated in experimental design and assist with interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

Clifford J Rosen, M.D.: participated in experimental design and assist with interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

Mitchell B Schaffler, Ph.D.: participated in experimental design and assist with interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

Shoshana Yakar, Ph.D.: initiate, design and coordinate the studies, data collection, analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Li M, Xu Y, Xu M, Ma L, Wang T, Liu Y, Dai M, Chen Y, Lu J, Liu J, et al. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and osteoporotic fracture in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):2033–2038. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luxon BA. Bone disorders in chronic liver diseases. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(1):40–48. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon SS, Lee YS, Kim SW. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with low bone mass in postmenopausal women. Endocrine. 2012;42(2):423–429. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardee PE, Dunn W, Schwimmer JB. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with low bone mineral density in obese children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(2):248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirgon O, Bilgin H, Tolu I, Odabas D. Correlation of insulin sensitivity with bone mineral status in obese adolescents with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75(2):189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purnak T, Beyazit Y, Ozaslan E, Efe C, Hayretci M. The evaluation of bone mineral density in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(15–16):526–531. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marek B, Kajdaniuk D, Niedziolka D, Borgiel-Marek H, Nowak M, Sieminska L, Ostrowska Z, Glogowska-Szelag J, Piecha T, Otremba L, et al. Growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 axis, calciotropic hormones and bone mineral density in young patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Endokrynol Pol. 2015;66(1):22–29. doi: 10.5603/EP.2015.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lupoli R, Di Minno A, Spadarella G, Ambrosino P, Panico A, Tarantino L, Lupoli G, Di Minno MN. The risk of osteoporosis in patients with liver cirrhosis: a meta-analysis of literature studies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2016;84(1):30–38. doi: 10.1111/cen.12780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raslan HM, Elhosary Y, Ezzat WM, Rasheed EA, Rasheed MA. The potential role of insulin-like growth factor 1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 and bone mineral density in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus in Cairo, Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104(6):429–432. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George J, Ganesh HK, Acharya S, Bandgar TR, Shivane V, Karvat A, Bhatia SJ, Shah S, Menon PS, Shah N. Bone mineral density and disorders of mineral metabolism in chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(28):3516–3522. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaudio A, Lasco A, Morabito N, Atteritano M, Vergara C, Catalano A, Fries W, Trifiletti A, Frisina N. Hepatic osteodystrophy: does the osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand system play a role? J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28(8):677–682. doi: 10.1007/BF03347549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakatos PL, Bajnok E, Tornai I, Folhoffer A, Horvath A, Lakatos P, Szalay F. Decreased bone mineral density and gene polymorphism in primary biliary cirrhosis. Orv Hetil. 2004;145(7):331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taveira AT, Pereira FA, Fernandes MI, Sawamura R, Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Paula FJ. Longitudinal evaluation of hepatic osteodystrophy in children and adolescents with chronic cholestatic liver disease. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43(11):1127–1134. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2010007500118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Albuquerque Taveira AT, Fernandes MI, Galvao LC, Sawamura R, de Mello Vieira E, de Paula FJ. Impairment of bone mass development in children with chronic cholestatic liver disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66(4):518–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handzlik-Orlik G, Holecki M, Wilczynski K, Dulawa J. Osteoporosis in liver disease: pathogenesis and management. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2016;7(3):128–135. doi: 10.1177/2042018816641351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez-Larramona G, Lucendo AJ, Tenias JM. Association between nutritional screening via the Controlling Nutritional Status index and bone mineral density in chronic liver disease of various etiologies. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(6):618–628. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Larramona G, Lucendo AJ, Gonzalez-Castillo S, Tenias JM. Hepatic osteodystrophy: An important matter for consideration in chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2011;3(12):300–307. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i12.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goral V, Simsek M, Mete N. Hepatic osteodystrophy and liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(13):1639–1643. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collier JD, Ninkovic M, Compston JE. Guidelines on the management of osteoporosis associated with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 1):i1–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.suppl_1.i1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgert TS, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Goodman TR, Yeckel CW, Papademetris X, Constable RT, Weiss R, Tamborlane WV, Savoye M, et al. Alanine aminotransferase levels and fatty liver in childhood obesity: associations with insulin resistance, adiponectin, and visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4287–4294. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G, Pearson WS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adolescents using the definition from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):587–589. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the pediatric population. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8(3):549–558. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangun O, Dundar B, Kosker M, Pirgon O, Dundar N. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese children and adolescents using three different criteria and evaluation of risk factors. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3(2):70–76. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.v3i2.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu NY, Wolfson T, Middleton MS, Hamilton G, Gamst A, Angeles JE, Schwimmer JB, Sirlin CB. Bone marrow fat content is correlated with hepatic fat content in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Radiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilmaz Y. Review article: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and osteoporosis--clinical and molecular crosstalk. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(4):345–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos RM, de Piano A, da Silva PL, Carnier J, Sanches PL, Corgosinho FC, Masquio DC, Lazaretti-Castro M, Oyama LM, Nascimento CM, et al. The role of pro/anti-inflammatory adipokines on bone metabolism in NAFLD obese adolescents: effects of long-term interdisciplinary therapy. Endocrine. 2012;42(1):146–156. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yakar S, Isaksson O. Regulation of skeletal growth and mineral acquisition by the GH/IGF-1 axis: Lessons from mouse models. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2016;28:26–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Cordoba-Chacon J, Kineman RD, Cronstein BN, Muzumdar R, Gong Z, Werner H, Yakar S. Growth Hormone Control of Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. Diabetes. 2016;65(12):3598–3609. doi: 10.2337/db16-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan Y, Menon RK, Cohen P, Hwang D, Clemens T, DiGirolamo DJ, Kopchick JJ, Le Roith D, Trucco M, Sperling MA. Liver-specific deletion of the growth hormone receptor reveals essential role of growth hormone signaling in hepatic lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):19937–19944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson CG, Tran JL, Erion DM, Vera NB, Febbraio M, Weiss EJ. Hepatocyte-Specific Disruption of CD36 Attenuates Fatty Liver and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in HFD-Fed Mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(2):570–585. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordstrom SM, Tran JL, Sos BC, Wagner KU, Weiss EJ. Disruption of JAK2 in adipocytes impairs lipolysis and improves fatty liver in mice with elevated GH. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(8):1333–1342. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui Y, Hosui A, Sun R, Shen K, Gavrilova O, Chen W, Cam MC, Gao B, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Loss of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 leads to hepatosteatosis and impaired liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2007;46(2):504–513. doi: 10.1002/hep.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtland HW, DeMambro V, Maynard J, Sun H, Elis S, Rosen C, Yakar S. Sex-specific regulation of body size and bone slenderness by the acid labile subunit. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(9):2059–2068. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yakar S, Canalis E, Sun H, Mejia W, Kawashima Y, Nasser P, Courtland HW, Williams V, Bouxsein M, Rosen C, et al. Serum IGF-1 determines skeletal strength by regulating subperiosteal expansion and trait interactions. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(8):1481–1492. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.090226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, Sun H, Basta-Pljakic J, Cardoso L, Kennedy OD, Jasper H, Domene H, Karabatas L, Guida C, Schaffler MB, et al. Serum IGF-1 is insufficient to restore skeletal size in the total absence of the growth hormone receptor. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(7):1575–1586. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elis S, Wu Y, Courtland HW, Sun H, Rosen CJ, Adamo ML, Yakar S. Increased serum IGF-1 levels protect the musculoskeletal system but are associated with elevated oxidative stress markers and increased mortality independent of tissue igf1 gene expression. Aging Cell. 2011;10(3):547–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elis S, Courtland HW, Wu Y, Fritton JC, Sun H, Rosen CJ, Yakar S. Elevated serum IGF-1 levels synergize PTH action on the skeleton only when the tissue IGF-1 axis is intact. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(9):2051–2058. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elis S, Courtland HW, Wu Y, Rosen CJ, Sun H, Jepsen KJ, Majeska RJ, Yakar S. Elevated serum levels of IGF-1 are sufficient to establish normal body size and skeletal properties even in the absence of tissue IGF-1. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(6):1257–1266. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hegedus C, Robaszkiewicz A, Lakatos P, Szabo E, Virag L. Poly(ADP-ribose) in the bone: from oxidative stress signal to structural element. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;82:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onal M, Piemontese M, Xiong J, Wang Y, Han L, Ye S, Komatsu M, Selig M, Weinstein RS, Zhao H, et al. Suppression of autophagy in osteocytes mimics skeletal aging. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17432–17440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jilka RL, Almeida M, Ambrogini E, Han L, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC. Decreased oxidative stress and greater bone anabolism in the aged, when compared to the young, murine skeleton with parathyroid hormone administration. Aging Cell. 2010;9(5):851–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banfi G, Iorio EL, Corsi MM. Oxidative stress, free radicals and bone remodeling. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(11):1550–1555. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Key LL, Jr, Wolf WC, Gundberg CM, Ries WL. Superoxide and bone resorption. Bone. 1994;15(4):431–436. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90821-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garrett IR, Boyce BF, Oreffo RO, Bonewald L, Poser J, Mundy GR. Oxygen-derived free radicals stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption in rodent bone in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1990;85(3):632–639. doi: 10.1172/JCI114485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Y, Sun H, Yakar S, LeRoith D. Elevated levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I in serum rescue the severe growth retardation of IGF-I null mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(9):4395–4403. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y, Wang C, Sun H, LeRoith D, Yakar S. High-efficient FLPo deleter mice in C57BL/6J background. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e8054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yakar S, Liu JL, Stannard B, Butler A, Accili D, Sauer B, LeRoith D. Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(13):7324–7329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR, Parfitt AM. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlecht SH, Jepsen KJ. Functional integration of skeletal traits: an intraskeletal assessment of bone size, mineralization, and volume covariance. Bone. 2013;56(1):127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silva BC, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid hormone: anabolic and catabolic actions on the skeleton. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;22:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okajima H, Shigeno C, Inomata Y, Egawa H, Uemoto S, Asonuma K, Kiuchi T, Konishi J, Tanaka K. Long-term effects of liver transplantation on bone mineral density in children with end-stage liver disease: a 2-year prospective study. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(4):360–364. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Du J, Pan X, Lu Z, Gao M, Hu X, Zhang X, Bao Y, Jia W. Serum osteocalcin levels are inversely associated with the presence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):21435–21441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang HJ, Shim SG, Ma BO, Kwak JY. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with bone mineral density and serum osteocalcin levels in Korean men. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(3):338–344. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo YQ, Ma XJ, Hao YP, Pan XP, Xu YT, Xiong Q, Bao YQ, Jia WP. Inverse relationship between serum osteocalcin levels and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in postmenopausal Chinese women with normal blood glucose levels. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(12):1497–1502. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu JJ, Chen YY, Mo ZN, Tian GX, Tan AH, Gao Y, Yang XB, Zhang HY, Li ZX. Relationship between serum osteocalcin levels and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adult males, South China. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):19782–19791. doi: 10.3390/ijms141019782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diez Rodriguez R, Ballesteros Pomar MD, Calleja Fernandez A, Calleja Antolin S, Cano Rodriguez I, Linares Torres P, Jorquera Plaza F, Olcoz Goni JL. Vitamin D levels and bone turnover markers are not related to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in severely obese patients. Nutr Hosp. 2014;30(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.30.6.7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dou J, Ma X, Fang Q, Hao Y, Yang R, Wang F, Zhu J, Bao Y, Jia W. Relationship between serum osteocalcin levels and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese men. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(4):282–288. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aller R, Castrillon JL, de Luis DA, Conde R, Izaola O, Sagrado MG, Velasco MC, Alvarez T, Pacheco D. Relation of osteocalcin with insulin resistance and histopathological changes of non alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10(1):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diamond TH, Stiel D, Lunzer M, McDowall D, Eckstein RP, Posen S. Hepatic osteodystrophy. Static and dynamic bone histomorphometry and serum bone Gla-protein in 80 patients with chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(1):213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosen CJ, Ackert-Bicknell C, Rodriguez JP, Pino AM. Marrow fat and the bone microenvironment: developmental, functional, and pathological implications. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19(2):109–124. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robaszkiewicz A, Erdelyi K, Kovacs K, Kovacs I, Bai P, Rajnavolgyi E, Virag L. Hydrogen peroxide-induced poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation regulates osteogenic differentiation-associated cell death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(8):1552–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mandal CC, Ganapathy S, Gorin Y, Mahadev K, Block K, Abboud HE, Harris SE, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Ghosh-Choudhury N. Reactive oxygen species derived from Nox4 mediate BMP2 gene transcription and osteoblast differentiation. Biochem J. 2011;433(2):393–402. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nojiri H, Saita Y, Morikawa D, Kobayashi K, Tsuda C, Miyazaki T, Saito M, Marumo K, Yonezawa I, Kaneko K, et al. Cytoplasmic superoxide causes bone fragility owing to low-turnover osteoporosis and impaired collagen cross-linking. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(11):2682–2694. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):27298–27305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smietana MJ, Arruda EM, Faulkner JA, Brooks SV, Larkin LM. Reactive oxygen species on bone mineral density and mechanics in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase (Sod1) knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;403(1):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Desler C, Marcker ML, Singh KK, Rasmussen LJ. The importance of mitochondrial DNA in aging and cancer. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:407536. doi: 10.4061/2011/407536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olivier BJ, Schoenmaker T, Mebius RE, Everts V, Mulder CJ, van Nieuwkerk KM, de Vries TJ, van der Merwe SW. Increased osteoclast formation and activity by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in chronic liver disease patients with osteopenia. Hepatology. 2008;47(1):259–267. doi: 10.1002/hep.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cuthbert JA, Pak CY, Zerwekh JE, Glass KD, Combes B. Bone disease in primary biliary cirrhosis: increased bone resorption and turnover in the absence of osteoporosis or osteomalacia. Hepatology. 1984;4(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manolagas SC. The role of IL-6 type cytokines and their receptors in bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Bone marrow, cytokines, and bone remodeling. Emerging insights into the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(5):305–311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfeilschifter J, Chenu C, Bird A, Mundy GR, Roodman GD. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor stimulate the formation of human osteoclastlike cells in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4(1):113–118. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bertolini DR, Nedwin GE, Bringman TS, Smith DD, Mundy GR. Stimulation of bone resorption and inhibition of bone formation in vitro by human tumour necrosis factors. Nature. 1986;319(6053):516–518. doi: 10.1038/319516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sucur A, Katavic V, Kelava T, Jajic Z, Kovacic N, Grcevic D. Induction of osteoclast progenitors in inflammatory conditions: key to bone destruction in arthritis. Int Orthop. 2014;38(9):1893–1903. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2386-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pacifici R. Osteoimmunology and its implications for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2245–2254. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Benedetti F. The impact of chronic inflammation on the growing skeleton: lessons from interleukin-6 transgenic mice. Horm Res. 2009;72(Suppl 1):26–29. doi: 10.1159/000229760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1186–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitchell R, McDermid J, Ma MM, Chik CL. MELD score, insulin-like growth factor 1 and cytokines on bone density in end-stage liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2011;3(6):157–163. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i6.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Natale VM, Jacob Filho W, Duarte AJ. Does the secretion of cytokines in the periphery reflect their role in bone metabolic diseases? Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;94(1–3):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gur A, Dikici B, Nas K, Bosnak M, Haspolat K, Sarac AJ. Bone mineral density and cytokine levels during interferon therapy in children with chronic hepatitis B: does interferon therapy prevent from osteoporosis? BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guanabens N, Enjuanes A, Alvarez L, Peris P, Caballeria L, Jesus Martinez de Osaba M, Cerda D, Monegal A, Pons F, Pares A. High osteoprotegerin serum levels in primary biliary cirrhosis are associated with disease severity but not with the mRNA gene expression in liver tissue. J Bone Miner Metab. 2009;27(3):347–354. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yilmaz Y, Ozturk O, Alahdab YO, Senates E, Colak Y, Doganay HL, Coskunpinar E, Oltulu YM, Eren F, Atug O, et al. Serum osteopontin levels as a predictor of portal inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bertola A, Deveaux V, Bonnafous S, Rousseau D, Anty R, Wakkach A, Dahman M, Tordjman J, Clement K, McQuaid SE, et al. Elevated expression of osteopontin may be related to adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and liver steatosis in morbid obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58(1):125–133. doi: 10.2337/db08-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Duncan EL, Danoy P, Kemp JP, Leo PJ, McCloskey E, Nicholson GC, Eastell R, Prince RL, Eisman JA, Jones G, et al. Genome-wide association study using extreme truncate selection identifies novel genes affecting bone mineral density and fracture risk. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(4):e1001372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koller DL, Ichikawa S, Lai D, Padgett LR, Doheny KF, Pugh E, Paschall J, Hui SL, Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, et al. Genome-wide association study of bone mineral density in premenopausal European-American women and replication in African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1802–1809. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, Jonsdottir T, Saemundsdottir J, Snorradottir S, Center JR, et al. New sequence variants associated with bone mineral density. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):15–17. doi: 10.1038/ng.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trost Z, Trebse R, Prezelj J, Komadina R, Logar DB, Marc J. A microarray based identification of osteoporosis-related genes in primary culture of human osteoblasts. Bone. 2010;46(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malaval L, Wade-Gueye NM, Boudiffa M, Fei J, Zirngibl R, Chen F, Laroche N, Roux JP, Burt-Pichat B, Duboeuf F, et al. Bone sialoprotein plays a functional role in bone formation and osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med. 2008;205(5):1145–1153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gene expression in livers dissected from male mice at the indicated ages (N>6 per group per age). Data presented as mean ± SEM. Significance accepted at p<0.05, a-vs. control, b-vs. HIT, c-vs Li-GHRKO.