Abstract

Objective

Acute renal replacement therapy (RRT) in patients with sepsis has increased dramatically with substantial costs. However, the extent of variability in use across hospitals—and whether greater use is associated with better outcomes—is unknown.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) in 2011

Patients

Aged 18 years and older with sepsis and acute kidney injury (AKI) admitted to hospitals sampled by the NIS in 2011

Interventions

We estimated the risk- and reliability-adjusted rate of acute RRT use for patients with sepsis and AKI at each hospital. We examined the association between hospital-specific RRT rate and in-hospital mortality and hospital costs after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics.

Measurements and Main Results

We identified 293,899 hospitalizations with sepsis and AKI at 440 hospitals, of which 6.4% (n = 18,885) received RRT. After risk- and reliability-adjustment, the median hospital RRT rate for patients with sepsis and AKI was 3.6% (IQR 2.9–4.5%). However, hospitals in the top quintile of RRT use had rates ranging from 4.8% to 13.4%. There was no significant association between hospital-specific RRT rate and in-hospital mortality (OR per 1% increase in RRT rate: 1.03, 95% CI 0.99–1.07, P = 0.10). Hospital costs were significantly higher with increasing RRT rates (absolute cost increase per 1% increase in RRT rate: $1,316, 95% CI: $157-$2,475, P = 0.03).

Conclusions

RRT use in sepsis varied widely among nationally sampled hospitals without association with mortality. Improving RRT initiation standards for sepsis may reduce healthcare costs without increasing mortality.

Keywords: sepsis, renal replacement therapy, acute kidney injury, outcomes research, epidemiology

Introduction

Multiple studies, including randomized trials, have examined the timing of renal replacement therapy (RRT) among critically ill patients, with mixed results. Some have demonstrated a mortality benefit to early initiation of RRT,(1–3) while others have suggested no difference when RRT initiation is delayed.(4, 5) This conflicting evidence makes the dual decisions of whether and when to initiate RRT for patients with sepsis challenging for clinicians and may lead to substantial variation in practices surrounding the initiation of RRT for sepsis.

The use of renal replacement therapy during acute hospitalizations has increased substantially over the past two decades,(6–8) particularly among patients with sepsis.(6, 7, 9–12) While the optimal strategy for RRT initiation remains uncertain, patterns of RRT use may provide a glimpse into real-world care provided to patients with sepsis. Early RRT delivery may reduce mortality in the severely ill or could result in unnecessary treatment with increased costs without mortality benefit.(13, 14)

We sought to investigate associations between hospital rates of RRT for sepsis and patient outcomes. Because of the insufficient evidence available to guide clinicians, we hypothesized that there would be substantial variation in RRT use for patients with sepsis. We believed that this variation would result in higher costs for some without improvement in mortality.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project – Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS).(15) The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient health care database in the U.S, including data from 44 states and the District of Columbia. NIS data from 2011 contain all hospitalizations of a 20% stratified sample of U.S. hospitals. Data from 2011 were used because beginning in 2012, the NIS changed its sampling strategy. Rather than identifying all discharges from 20% of hospitals, it identified 20% of discharges from all hospitals.(15)

We included patients aged 18 and older hospitalized with severe sepsis and acute kidney injury (AKI) in 2011. Patients with severe sepsis were defined by having International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes for infection and acute organ dysfunction (eTable 1).(16) This strategy to identify sepsis from administrative data has a specificity of 96.3% and a positive predictive value of 70.7%.(17) AKI was defined by ICD-9-CM diagnosis code (584.X),(6) and RRT use was identified by ICD-9-CM procedure code (39.95).(6) The combination of ICD-9-CM codes for AKI and RRT has been validated against chart review and has a positive predictive value of 95.0% and a negative predictive value of 90.0%.(18, 19) We excluded patients admitted to hospitals without RRT capabilities (defined by less than 5 patients receiving RRT in 2011), patients transferred from another hospital (as they may have been initiated on RRT at another hospital), patients with a history of end-stage renal disease (ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 585.6 or procedure codes 39.95 or 54.98 and the absence of ICD-9-CM code for AKI),(20) or patients who died within 24 hours of hospital admission because they may not have had enough time to be initiated on RRT.

The primary exposure variable was the proportion of patients receiving RRT out of all hospitalized patients with sepsis and AKI. The primary outcome was hospital-level risk-adjusted mortality rate (number of in-hospital deaths per 100 patients with sepsis and AKI). Mortality was defined as in-hospital death from any cause. We examined the association between hospital RRT rate and patient-level outcomes, such as in-hospital mortality and hospital costs. Hospital costs were calculated by the patient’s total hospital charges multiplied by the 2011 hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio.(21)

We identified the total number and the proportion of patients with sepsis and AKI, who received RRT. Hospitals were ranked and assigned to quintiles based upon the distribution of RRT rates for sepsis and AKI. We also identified the total number and the proportion among all hospitalized patients, who received RRT, at each hospital.

Statistical analysis

For each hospital, we estimated hospital-specific RRT and mortality rates using hierarchical logistic regression for risk- and reliability-adjustment.(22) This approach accounts for baseline differences between patients and hospitals and controls for the lower precision of RRT rates for hospitals with few patients.(23) Hospitals using RRT frequently will have estimates approximating their actual rates while hospitals using less RRT will have their rates weighted towards the mean RRT rate for the sample of hospitals.(22, 23)

Risk-adjustment was performed to control for any baseline differences between patients and included covariates such as age, sex, race, primary insurance, residential location as stratified by the National Center for Health Statistics Urban/Rural Classification Scheme,(24) preexisting comorbidities according to Elixhauser et al,(25) and severity of illness. Severity of illness was captured using secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedural codes for acute organ dysfunction,(16) mechanical ventilation,(26) respiratory failure, sepsis, shock, AKI requiring RRT, cardiac or respiratory arrest, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Hospital-level variables were obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals and included in the NIS. Hospital-level risk adjustment included hospital type (not-for-profit, for-profit, government), hospital size (based on hospital beds and specific to the hospital’s location and teaching status),(27) teaching status (defined by whether the hospital has a ratio of 0.25 or higher of full-time equivalent interns and residents to hospital beds),(27) annual volume of sepsis cases, annual volume of AKI, urbanicity (urban/rural), U.S. region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), hospital nursing ratio (number of registered nurse full-time equivalents per 1,000 patient days).(27)

We compared patient and hospital characteristics across hospitals by quintiles of RRT rates using chi-square tests. To evaluate whether hospital-level RRT rates for patients with sepsis and AKI were associated with hospital-level mortality rates, we performed Spearman’s rank correlations. We also used Spearman’s rank correlations to assess the association between a hospital’s RRT rate for AKI and sepsis and its RRT rate for all hospitalized patients. To examine the association of hospital-level RRT rates with patient-level outcomes, we used generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors with clustering at the hospital level and a logit (mortality) or identity (costs) link.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed two sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, we theorized that patients most likely to benefit from RRT would be the most severely ill subgroup of patients. To evaluate whether increased hospital use of RRT might benefit this population of patients, we performed a sensitivity analysis including only severely ill patients with sepsis and AKI. These patients were defined by ICD-9-CM codes for mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, shock, or cardiopulmonary arrest.(28) We then evaluated associations between hospital RRT rate and patient-level mortality using generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors with clustering at the hospital level and a logit link function.

Second, we used the 2014 New York state database to assess whether patterns of RRT use for sepsis had changed since 2011. We identified all patients with sepsis and AKI, then calculated risk- and reliability-adjusted RRT rates for all New York hospitals. We then used Spearman’s rank correlations to assess the association between a hospital’s RRT rate for sepsis and AKI and its overall RRT rate.

Data management and analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC) and Stata 14.1 (College Station, TX). All tests were two-sided with a P value < 0.05 considered significant. The Institutional Review Board for the University of Michigan approved the study and provided a waiver of consent (HUM00053488).

Results

We identified 440 hospitals treating 293,899 patients with sepsis and AKI, of which 18,885 (6.4%) patients received RRT (eFigure 1). The average age of patients with sepsis and AKI was 70.5 (SD 15.7). Most patients were female (50.8%), white (62.1%), and had Medicare as their primary insurer (70.7%). Crude hospital mortality was 9.9% among all patients with sepsis and AKI and was 22.6% among patients with sepsis and AKI receiving RRT.

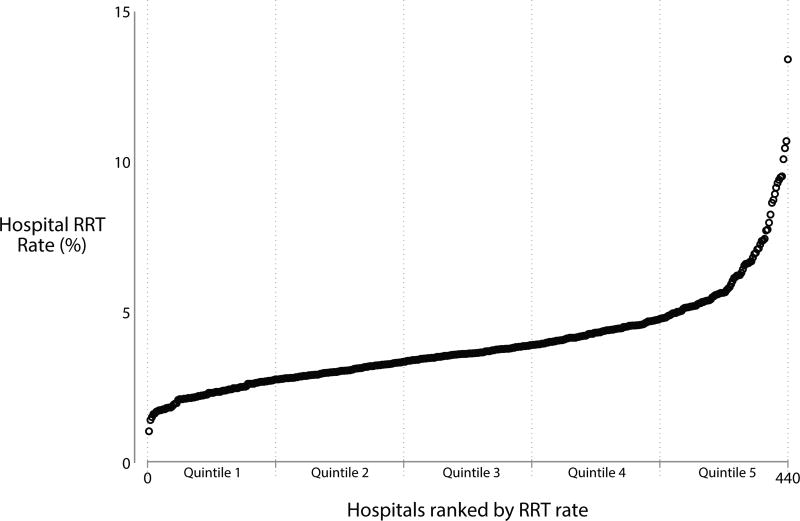

The median hospital case-volume for RRT among patients with sepsis and AKI in 2011 was 30 (IQR 13–60). Hospitals that performed more RRT overall tended to perform RRT at a higher rate for patients with sepsis and AKI (r = 0.59, P < 0.001). After risk- and reliability-adjustment, the median RRT rate for patients with sepsis and AKI was 3.6% (range 1.7–13.4%; IQR 2.9–4.5%) (Figure 1). Hospital quintiles of RRT rates for sepsis and AKI were 1.7–2.8%, 2.8–3.3%, 3.4–3.8%, 3.9–4.8%, and 4.8–13.4%.

Figure 1.

There were no substantial differences in characteristics of hospitals in the highest quintile of RRT use and all other hospitals (Table 1). There were several clinically meaningful differences between patients in hospitals with the highest RRT use and patients admitted to all other hospitals. For example, patients in high-RRT use hospitals were more likely to be older, have a race/ethnicity other than white, live rurally, have lower median household income, and were more likely to have comorbidities such as heart failure or chronic pulmonary disease (Table 2).

Table 1.

Hospital characteristics by hospital RRT rates

| Hospital characteristics |

Quintile 1 (1.1–2.8%) |

Quintile 2 (2.9–3.4%) |

Quintile 3 (3.5–4.0%) |

Quintile 4 (4.1–4.7%) |

Quintile 5 (4.8–13.4%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Hospitals | 88 (20.0) | 88 (20.0) | 88 (20.0) | 88 (20.0) | 88 (20.0) |

| Hospital Type* | |||||

| For-profit | 21.6 | 23.9 | 29.6 | 23.9 | 21.6 |

| Not-for-profit | 68.2 | 62.5 | 65.9 | 70.5 | 68.2 |

| Government | 10.2 | 13.6 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 10.2 |

| Teaching Hospital | 31.8 | 31.8 | 34.1 | 31.8 | 33.0 |

| Hospital Size by Beds | |||||

| Small | 21.6 | 19.3 | 25.0 | 20.5 | 21.6 |

| Medium | 31.8 | 30.7 | 34.1 | 19.3 | 34.1 |

| Large | 46.6 | 50.0 | 40.9 | 60.2 | 44.3 |

| Census Regions | |||||

| Northeast | 15.9 | 12.5 | 21.6 | 20.5 | 13.6 |

| Midwest | 22.7 | 27.3 | 21.6 | 26.1 | 23.9 |

| South | 39.8 | 38.6 | 36.4 | 35.2 | 43.2 |

| West | 21.6 | 21.6 | 20.5 | 18.2 | 19.3 |

| Urbanity | |||||

| Rural | 11.4 | 14.8 | 9.1 | 11.4 | 12.5 |

| Urban | 88.6 | 85.2 | 90.9 | 88.6 | 87.5 |

| Quartiles of Nursing FTE per 1000 Patient-Days | |||||

| 1 (< 2.9) | 23.9 | 27.3 | 31.8 | 27.3 | 23.9 |

| 2 (2.9–3.8) | 20.5 | 25.0 | 23.9 | 26.1 | 28.4 |

| 3 (3.9–4.6) | 30.7 | 26.1 | 14.8 | 21.6 | 23.9 |

| 4 (> 4.6) | 25.0 | 21.6 | 29.6 | 25.0 | 23.9 |

| Quartiles of Volume of Admissions with Sepsis | |||||

| 1 (< 406) | 27.3 | 20.5 | 31.8 | 20.5 | 27.3 |

| 2 (407–866) | 26.1 | 30.7 | 22.7 | 20.5 | 22.7 |

| 3 (867–1444) | 25.0 | 23.9 | 20.5 | 29.6 | 27.3 |

| 4 (> 1444) | 21.6 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 29.6 | 22.7 |

| Quartiles of Volume of Admissions with AKI | |||||

| 1 (< 218) | 27.3 | 20.5 | 31.8 | 20.5 | 27.3 |

| 2 (219–480) | 26.1 | 30.7 | 22.7 | 20.5 | 22.7 |

| 3 (481–838) | 25.0 | 23.9 | 20.5 | 29.6 | 27.3 |

| 4 (> 838) | 21.6 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 29.6 | 22.7 |

Percent unless otherwise specified

Table 2.

Patient characteristics by hospital RRT rates

| Patient characteristics | Quintile 1 (1.1–2.8%) |

Quintile 2 (2.9–3.4%) |

Quintile 3 (3.5–4.0%) |

Quintile 4 (4.1–4.7%) |

Quintile 5 (4.8–13.4%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 58,305 (19.8) | 62,915 (21.4) | 56,272 (19.2) | 70,470 (24.0) | 45,937 (15.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 70 (16) | 70 (16) | 70 (16) | 70 (16) | 71 (15) |

| 18–44* | 7.0 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 5.8 |

| 45–64 | 26.8 | 26.5 | 26.2 | 26.3 | 24.5 |

| 65–79 | 33.1 | 33.1 | 33.8 | 33.1 | 35.3 |

| ≥ 80 | 33.1 | 34.0 | 33.8 | 34.0 | 34.4 |

| Female | 52.1 | 50.9 | 51.1 | 49.8 | 50.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 62.4 | 57.2 | 64.1 | 65.4 | 60.8 |

| Black | 17.7 | 13.7 | 15.7 | 14.2 | 13.4 |

| Other | 7.2 | 12.5 | 16.3 | 13.2 | 16.1 |

| Missing | 12.8 | 16.6 | 3.9 | 7.2 | 9.8 |

| Urbanicity | |||||

| Large Central | 24.9 | 36.9 | 47.9 | 44.5 | 39.2 |

| Large Fringe | 31.1 | 24.6 | 22.7 | 27.7 | 21.5 |

| Medium metropolitan | 20.8 | 18.8 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 15.9 |

| Small metropolitan | 8.0 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 6.0 | 10.4 |

| Micropolitan | 9.0 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 7.8 |

| Non-core | 6.2 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 5.3 |

| Median household income by ZIP code | |||||

| < $39,000 | 29.1 | 28.3 | 31.8 | 24.1 | 28.6 |

| $39,000–$47,999 | 22.7 | 24.0 | 21.5 | 23.4 | 26.0 |

| $48,000–$63,999 | 25.0 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 29.8 | 26.7 |

| ≥ $64,000 | 23.2 | 19.9 | 21.1 | 22.7 | 18.8 |

| Primary insurance | |||||

| Medicare | 69.9 | 70.7 | 70.9 | 69.3 | 73.5 |

| Medicaid | 7.8 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 8.4 |

| Private | 17.0 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 16.0 | 14.1 |

| Self-Pay | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.2 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) |

| Congestive heart failure | 31.2 | 31.9 | 33.8 | 34.0 | 36.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 38.9 | 44.4 | 45.4 | 47.0 | 50.1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 24.6 | 26.1 | 27.0 | 27.3 | 29.8 |

Percent unless otherwise specified

There was no association between hospital-level RRT rate for sepsis and AKI and hospital risk-adjusted mortality rate (r = 0.07, P = 0.15). A hospital’s RRT rate for sepsis and AKI was not associated with patient-level mortality after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics (OR for mortality per 1% increase in RRT rate: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.99–1.07, P = 0.10). However, patients with sepsis and AKI admitted to hospitals that used RRT more frequently had higher hospital costs (absolute cost increase per 1% increase in RRT rate: $1,316, 95% CI: $157-$2,475, P = 0.03).

Our sensitivity analyses were consistent with our primary results. There was no significant association between hospital-level RRT rate and patient-level mortality in the subgroup of 74,033 severely ill patients with sepsis and AKI (OR for mortality per 1% increase in RRT rate: 1.02, 95% CI 0.99–1.04, P = 0.20). Using 2014 New York state data, we identified 101,262 patients with sepsis and AKI in 122 hospitals. Hospital RRT rates ranged from 1.4% to 14.6% (median 5.7%, IQR 4.2–7.2) (eFigure 3). We found no association between hospital-level RRT rate for sepsis and AKI and hospital risk-adjusted mortality rate (r = 0.10, P = 0.28). Approximately 33.4% (n = 2,086) of patients with sepsis and AKI who received RRT were admitted to the general ward.

Discussion

We identified wide variation across hospitals in the use of RRT for patients with sepsis, independent of severity of illness. Some hospitals used RRT for 1 out of every 7 patients with sepsis, while other hospitals used RRT for 1 out of every 60 similar patients. Given the variation in RRT use between hospitals and the incidence of sepsis in the United States, this difference may affect approximately 170,000 Americans each year.(16, 29)

Our study used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, an administrative database, to evaluate variation between U.S. hospitals in RRT rates for patients with sepsis. For this analysis, the NIS dataset has several strengths. It provides a national perspective of hospital billing and practice, is commonly used for clinical research with methods validated against chart review, and includes all hospitalized patients, regardless of insurance coverage.

However, the NIS also has limitations that must be acknowledged. First, administrative data may imperfectly identify patients. However, we used definitions of sepsis,(17) AKI,(18) and RRT,(19) to identify patients that were previously validated against chart review. Second, the use of administrative data may inadequately account for differences between patients and hospitals. The NIS lacks clinical variables to adjust for many factors important to the decision to start RRT, such as severity of illness scores, laboratory values, or urine output. To account for these limitations, we performed risk-adjustment using all available data from the NIS, though residual confounding cannot be excluded. Third, the NIS database is unable to differentiate between intermittent or continuous RRT, how many RRT treatments a patient received, or what type of provider initiated RRT. Fourth, the NIS is unable to establish whether patients were treated in an ICU or general ward. However, our sensitivity analysis using New York state data demonstrated one-third of sepsis patients receiving RRT were treated in the general ward. Finally, the NIS database maintains a unique identifier for each hospitalization but not for each patient. Thus, readmissions and post-discharge outcomes are not captured. For instance, the NIS measures only in-hospital mortality. However, hospital discharge practices may bias in-hospital mortality as an outcome compared to 30-day mortality.(30) To account for the limitations of the NIS, we have followed published, best-practice guidelines for the use of NIS and other administrative databases.(31–33)

RRT is undoubtedly beneficial for patients with select life-threatening electrolyte abnormalities, who require emergent RRT. However, among patients with sepsis, without these clear indications, there is no consensus to guide clinicians when deciding who should receive RRT and when to initiate.(34) This decision is complex, particularly given the current state of equipoise. Two recent randomized trials demonstrated mixed results between early and late initiation of RRT among critically ill patients, though they used slightly different populations.(1, 5) Observational studies have also failed to tip the scales in either direction.(2, 9, 35–38)

This conflict is reflected in the variation in RRT rates noted in this study. This analysis is unable to identify the underlying mechanisms driving RRT use, an area in which additional research is needed. However, there are a number of potential causes for this variation, ranging from hospital to clinician to patient factors. Hospitals may have differing capabilities to provide RRT for sepsis, such as dedicated equipment or access to RRT-trained specialists. Hospitals with more expertise in RRT may be more likely to initiate RRT on septic patients without clear-cut indications. For example, in another study, hospitals that used non-invasive ventilation frequently were more likely to provide non-invasive ventilation to patients outside of evidence-based indications.(39) Similarly, we found hospitals that used RRT more for all causes were more likely to initiate RRT for sepsis, for better or worse. We also found evidence of regional variation in care provided for patients with sepsis. Southern hospitals were more likely to use RRT than hospitals in other regions of the U.S. The reason for this finding could not be evaluated further but could potentially be related to either southern hospitals caring for sicker patients or RRT initiation practices that differ from other regions of the country. This pattern of geographic variation in healthcare has also been noted in other practices such as ICU utilization for heart failure and tracheostomy placement for mechanically ventilated patients.(40, 41)

This study complements past work that has demonstrated unwarranted variation and overuse in care provided to severely ill patients without obvious improvement in patient outcomes. Life-sustaining therapies in critical care such as tracheostomy, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and ICU admission are often necessary to prevent death.(41–43) In some cases, this variation can help to identify key populations that might benefit from a therapy.(28) However, in most cases, discretionary use of these and other treatments results in substantial variation and excessive costs without obvious benefits to patients.(44–46) Comparably, our study found that greater hospital use of RRT was not associated with better outcomes but resulted in higher costs, suggesting that improving RRT use for sepsis may be an opportunity reduce healthcare costs without increasing mortality.

The results of this study should not be taken as an indictment of RRT for sepsis. This study cannot identify which patients benefit from RRT use and which do not. Rather, our results should represent a call to action. We highlight the need to improve standards for RRT initiation, as the most appropriate clinical scenarios for using RRT for sepsis remain uncertain. This represents a genuine opportunity to improve patient-centered care and reduce healthcare costs.

Our study has important implications for patients, clinicians, and hospital administrators. When RRT is initiated, patients and families are confronted with a number of complex issues, such as procedures, costs, long-term recovery, and treatment withdrawal.(47, 48) Clinicians and hospital administrators must consider the resource-utilization necessary to initiate RRT in the acutely ill patient.(49) This study presents real-world evidence of the need to improve criteria to guide clinicians when deciding whether to initiate RRT for sepsis. Differences in RRT utilization between hospitals, noted in this study, in the absence of meaningful mortality differences suggests that RRT may be overused, perhaps in patients with weak indications for RRT. Thus, it is imperative to identify patients with sepsis who benefit from RRT and to evaluate at what point during a hospitalization RRT should be initiated.

Conclusion

Some hospitals use RRT for patients with sepsis four times more than the average hospital. Hospitals with higher RRT rates for sepsis had no difference in mortality with greater associated hospital costs. Improving RRT initiation standards for sepsis may reduce healthcare costs without increasing mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH T32HL007749 (TSV), the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D grant 13-079 (TJI), and AHRQ K08HS020672 (CRC).

Dr. Valley received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Nallamothu received funding from UnitedHealthcare and the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Conflicts: No conflicts of interest exist for the authors.

Author Contributions: Dr. Valley had full access to all of the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Valley, Cooke

Acquisition of data: Valley

Analysis and interpretation of data: Valley, Nallamothu, Heung, Iwashyna, Cooke

Drafting of the manuscript: Valley, Cooke

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Valley, Nallamothu, Heung, Iwashyna, Cooke

Statistical analysis: Valley, Cooke

Obtained funding: Cooke

Role of the sponsors: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: This manuscript does not necessarily represent the view of the U.S. Government or the Department of Veterans Affairs

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Iwashyna disclosed government work. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Zarbock A, Kellum JA, Schmidt C, et al. Effect of Early vs Delayed Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: The ELAIN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2190–2199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu KD, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, et al. Timing of initiation of dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2006;1:915–919. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, et al. Timing of renal replacement therapy and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury. Journal of Critical Care. 2009;24:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt GC, Das RR. Early versus late initiation of renal replacement therapy in patients with acute kidney injury-a systematic review & meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Nephrology. 2017;18:78. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, et al. Initiation Strategies for Renal-Replacement Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakhuja A, Kumar G, Gupta S, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Dialysis in Severe Sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015;192:951–957. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0329OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afshinnia F, Straight A, Li Q, et al. Trends in dialysis modality for individuals with acute kidney injury. Renal failure. 2009;31:647–654. doi: 10.3109/08860220903151401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navas a, Ferrer R, Martínez M, et al. Renal replacement therapy in the critical patient: treatment variation over time. Medicina intensiva / Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias. 2012;36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Kellum JA, et al. Association between renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury and mortality. J Crit Care. 2013;28(6):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou YH, Huang TM, Wu VC, et al. Impact of timing of renal replacement therapy initiation on outcome of septic acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R134. doi: 10.1186/cc10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R, et al. Early acute kidney injury and sepsis: a multicentre evaluation. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):R47. doi: 10.1186/cc6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:813–818. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauf AA, Long KH, Gajic O, et al. Intermittent hemodialysis versus continuous renal replacement therapy for acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: an observational outcomes analysis. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2001;23:195–203. doi: 10.1177/0885066608315743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Smedt DM, Elseviers MM, Lins RL, et al. Economic evaluation of different treatment modalities in acute kidney injury. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2012;27:4095–4101. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) doi: 10.7759/cureus.33111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwashyna TJ, Odden A, Rohde J, et al. Identifying Patients With Severe Sepsis Using Administrative Claims. Medical Care. 2014;52:39–43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268ac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes for Acute Renal Failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17:1688–1694. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlasschaert MEO, Bejaimal SaD, Hackam DG, et al. Validity of administrative database coding for kidney disease: A systematic review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2011;57:29–43. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakhuja A, Schold JD, Kumar G, et al. Outcomes of patients receiving maintenance dialysis admitted over weekends. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2013;62:763–770. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asper F. Calculating "Cost": Cost-to-Charge Ratios. Minneapolis, MN: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ash AS, Fienberg SE, Louis TA, et al. Statistical issues in assessing hospital performance. The COPSS-CMS White Paper Committee. 2012:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD. Ranking Hospitals on Surgical Mortality: The Importance of Reliability Adjustment. Health Services Research. 2010;45:1614–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Vital and health statistics Series 2, Data evaluation and methods research. 2014:1–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wunsch H, Kramer A, Gershengorn HB. Validation of Intensive Care and Mechanical Ventilation Codes in Medicare Data. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(7):e711–e714. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(HCUP) HCaUP. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2008 doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. No Title. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valley TS, Sjoding MW, Ryan AM, et al. Association of Intensive Care Unit Admission With Mortality Among Older Patients With Pneumonia. JAMA. 2015;314:1272–1279. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahn JM, Kramer AA, Rubenfeld GD. Transferring critically ill patients out of hospital improves the standardized mortality ratio: a simulation study. Chest. 2007;131:68–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nallamothu BK. Better-Not Just Bigger-Data Analytics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(7) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khera R, Krumholz HM. With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility: Big Data Research From the National Inpatient Sample. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(7) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke CR, Iwashyna TJ. Using existing data to address important clinical questions in critical care. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):886–896. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827bfc3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.John S, Eckardt KU. Renal replacement strategies in the ICU. Chest. 2007;132:1379–1388. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim CC, Tan CS, Kaushik M, et al. Initiating acute dialysis at earlier Acute Kidney Injury Network stage in critically ill patients without traditional indications does not improve outcome: A prospective cohort study. Nephrology. 2015;20:148–154. doi: 10.1111/nep.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clec'h C, Darmon M, Lautrette A, et al. Efficacy of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a propensity analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16(7):R236. doi: 10.1186/cc11905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaudry S, Ricard J-D, Leclaire C, et al. Acute kidney injury in critical care: Experience of a conservative strategy. Journal of Critical Care. 2014;29:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider AG, Uchino S, Bellomo R. Severe acute kidney injury not treated with renal replacement therapy: characteristics and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(3):947–952. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta AB, Douglas IS, Walkey AJ. Evidence-Based Utilization of Non-Invasive Ventilation and Patient Outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-208OC. AnnalsATS.201703-201208OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Safavi KC, Dharmarajan K, Kim N, et al. Variation exists in rates of admission to intensive care units for heart failure patients across hospitals in the United States. Circulation. 2013;127:923–929. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta AB, Syeda SN, Bajpayee L, et al. Trends in Tracheostomy for Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the United States, 1993–2012. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2015;192:446–454. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0239OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valley TS, Walkey AJ, Lindenauer PK, et al. Association Between Noninvasive Ventilation and Mortality Among Older Patients With Pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):e246–e254. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen LM, Render M, Sales A, et al. Intensive care unit admitting patterns in the Veterans Affairs health care system. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(16):1220–1226. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valley TS, Sjoding MW, Ryan AM, et al. Intensive Care Unit Admission and Survival among Older Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Heart Failure, or Myocardial Infarction. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):943–951. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-847OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Admon AJ, Seymour CW, Gershengorn HB, et al. Hospital-level variation in intensive care unit admission and critical care procedures for patients hospitalized for pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2014;146:1452–1461. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gershengorn HB, Wunsch H, Scales DC, et al. Association between arterial catheter use and hospital mortality in intensive care units. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1746–1754. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson RF, Gustin J. Acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit: impact on prognostic assessment for shared decision making. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(7):883–889. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hussain JA, Flemming K, Murtagh FEM, et al. Patient and Health Care Professional Decision-Making to Commence and Withdraw from Renal Dialysis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10:1201–1215. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11091114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagugli RM, Patera F, Battistoni S, et al. Six-year single-center survey on AKI requiring renal replacement therapy: epidemiology and health care organization aspects. Journal of Nephrology. 2015;28:339–349. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.