Abstract

The epidemic of violence disproportionately affects women, including Black women. Black women survivors of violence have been found to face multiple safety and health issues such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, HIV, and poor reproductive health. Many health issues co-occur, and this co-occurrence can be associated with additional safety and health-related challenges for survivors. Consequently, there is a need for multicomponent interventions that are designed to concurrently address multiple health issues commonly faced by Black survivors of violence. This systematic review of literature determines the efficacy of various strategies used in the existing evidence-based multicomponent interventions on violence reduction, promotion of reproductive health, reduction in risk for HIV, reduction in levels of stress, and improvement in mental health. Sixteen intervention studies were identified. Examples of components found to be efficacious in the studies were safety planning for violence, skill building in self-care for mental health, education and self-regulatory skills for HIV, mindfulness-based stress reduction for reducing stress, and individual counseling for reproductive health. Although some strategies were found to be efficacious in improving outcomes for survivors, the limitations in designs and methods, and exclusive focus on intimate partner violence calls for more rigorous research for this population, particularly for Black survivors of all forms of violence. There is also need for culturally responsive multicomponent interventions that account for diversity among Black survivors.

Keywords: multicomponent interventions, survivors of violence, Black women

Black women in the United States are at high risk of violence exposure (Catalano, Smoth, Snyder, & Rand, 2009; Thomas et al., 2012), with prevalence rates of lifetime violence reported to be 43.7% (Black et al., 2011). Violence victimization is a determinant of reproductive health problems (Salam, Alim, & Noguchi, 2006), poor mental health (Sabri et al., 2013; Sundermann, Chu, & DePrince, 2013), stress (Moffitt & Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank, 2013), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk (Stockman et al., 2013). Lifetime violence exposure may be a key factor contributing to health disparities among Black women; for instance, Black women with violence histories are especially susceptible to multiple health risks such as pregnancy complications, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), physical or physiological symptoms of stress, and HIV (Dailey, Humphreys, Rankin, & Lee, 2011; Long & Ullman, 2013). Co-occurring health problems are commonly found among survivors of violence (Mitchell, Wight, Heerden, & Rochat, 2016; Weaver, Gilbert, El-Bassel, Resnick, & Noursi, 2015) in the United States and globally. For instance, a recent systematic review of literature in Africa reported that 30% of women were affected by intimate partner violence (IPV), HIV, and mental health problems concurrently (Mitchell et al., 2016). In a study of Black women from the United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands (n = 431), severity of IPV was significantly associated with co-occurring mental health problems such as depression and PTSD (Sabri et al., 2013). Thus, efforts toward working with survivors of violence or reducing violence should incorporate addressing these multiple health outcomes among Black women.

Previous intervention studies have addressed factors such as violence, mental health, stress reduction, reproductive health, and HIV as separate issues. However, these factors are highly related and need a more comprehensive intervention approach. Since Black women are disproportionately burdened by violence and associated health concerns, comprehensive multi-component interventions that address their complex and co-occurring health needs may have greater impact on their overall health and well-being. Interventions that include one component and target one outcome do not account for multiple epidemics affecting Black survivors of violence. For instance, victimization-related distress in the form of PTSD increases the risk of other health problems such as depression and drug misuse (Breslau, Davis, Peterson, & Schultz, 1997; Sabri et al., 2013). Poor mental health may further entrap women in abusive relationships and interfere with their ability to access services in the community (Perez & Johnson, 2008; Sabri et al., 2013). Violence exposure among women is associated with substance use and an increased risk of HIV infection, with HIV infection often influenced by the psychosocial sequelae of violent victimization (Kimerling & Goldsmith, 2008). HIV infection in turn places women at higher risk of violence. Studies show HIV positive women in the United States experience violence at rates higher than the general population (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Abused women are more at risk of contracting HIV or sexually transmitted infections (STI) due to the inability to negotiate condom use with their abuser. Because these multiple health issues are interrelated, interventions focusing on any one of these issues in isolation may be less effective than the integrated approach (Kimerling & Goldsmith, 2008); to date, this remains an open question.

Some studies have reported effectiveness of single interventions for survivors. Few single-component interventions for survivors of violence (e.g., support group participation, Tutty, Bidgood, & Rothery, 1993; advocacy counseling services, Sullivan & Bybee, 1999) have shown improvement in some areas such as social support, improved quality of life (Wathen & MacMillan, 2003), improvement in self-esteem, internal locus of control, perceived stress, and marital functioning (Kaslow, Thorn, & Paranjape, 2006). However, the interventions or the outcomes assessed did not address other health concerns that are common sequelae of violence exposure.

Given the complexity of the multiple impacts of violence on women’s health in general, and Black women in particular, multicomponent interventions may offer more promise for improving health and safety for women survivors of violence. To date, there has been no systematic assessment of such efforts. Multicomponent interventions, however, require more resources and are inherently more complex to deliver and sustain (Squires, Sullivan, Eccles, Worswick, & Grimshaw, 2014). In order to ensure appropriate allocation of efforts and resources for multicomponent interventions for survivors, research is needed to establish an evidence base for intervention components that are effective in improving multiple outcomes for survivors. We conducted a systematic literature search to identify the evidence base for multicomponent interventions for Black survivors of violence, particularly those with lifetime trauma histories. We defined a multicomponent intervention as an intervention with a combination of multiple components that addressed two or more physical health, mental health, or safety outcomes for Black survivors of violence. The components of an intervention are parts of the content of the intervention, such as psychoeducation; case management; skills training; cognitive behavioral therapy; safety planning; relaxation exercises; or any other aspect of the intervention that could improve outcomes for Black survivors of violence. In this review, we focused on Black women residents of the United States, which comprise a diverse group with family ties in other regions of the world such as Africa, West Indies, or the Caribbean. The systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). The findings will be useful to identify gaps in existing literature and potential intervention components for a comprehensive multicomponent intervention for Black survivors of violence that addresses their multiple safety and health risks.

Purpose of the Study

In this article, we reviewed and synthesized literature

To describe the characteristics and effectiveness of evidence-based, integrated multicomponent intervention strategies for Black women survivors of violence; and

To determine the efficacy of various integrated multicomponent interventions strategies on the following individual outcomes for survivors of violence: violence reduction, reproductive health, reduced risk of HIV, reduced stress/stress management, and improved mental health.

Methods

Searches were conducted by the first author on the following five electronic databases: the PubMed, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Academic Search Complete, and Embase. In the search process, the intervention-related terms such as multicomponent, multi-component, integrated, comprehensive, intervention, program, randomized controlled trial, and random controlled trial were combined using Boolean connector “OR.” The violence-related terms such as “violence,” “abuse,” “assault,” “trauma,” “Intimate Partner Violence,” “Spouse Abuse,” “Domestic Violence,” “Battered Women,” “intimate partner violence,” “spouse abuse,” “spousal abuse,” “abused spouse,” “abused spouses,” “battered women,” “battered woman,” and “domestic violence” were also combined using Boolean connector “OR.” Further, using Boolean connector “OR,” we combined race/ethnicity and gender-related term such as “African,” “Black,” “African Americans,” “african american,” “african americans,” “black,” “blacks,” “female,” “females,” “woman,” and “women.” All the intervention-related terms, the violence-related terms, the race/ethnicity, and gender-related terms were combined using the Boolean connector “AND.” The maximum number of articles identified that included African Americans or Africans in the sample through these combinations of search terms was 1,717.

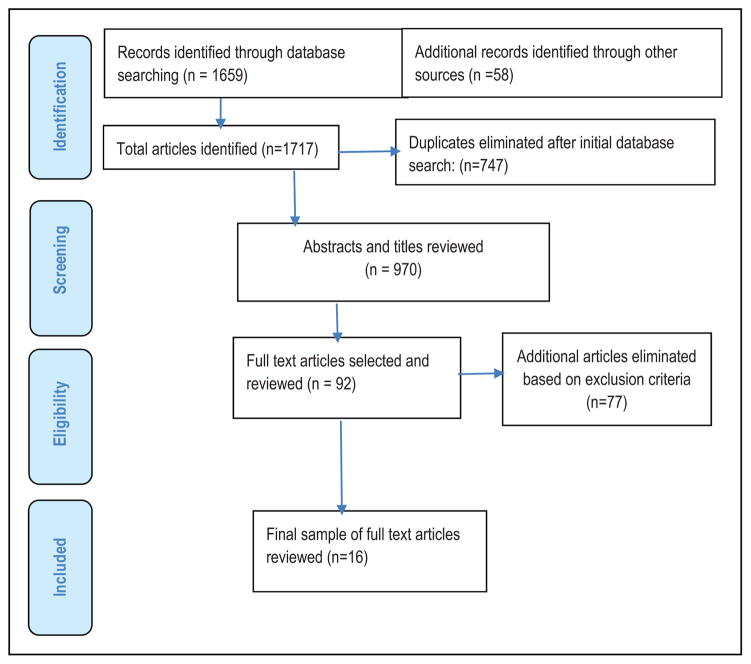

After removing duplicates (n = 747), 970 titles and abstracts were scanned for inclusion and exclusion. This screening resulted in the identification of 92 potentially relevant articles for which full-text copies were retrieved and reviewed by the first author. Publications were excluded if the abstracts and titles did not indicate discussion of an intervention or a program or did not include any of the targeted outcomes or exclusively focused on men or children under 18 years of age. When the abstract could not be excluded based on content presented, the article was reviewed in full. The 92 full-text articles were then reviewed based on the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria and a final set of 16 articles was identified by the first author, in consultation with the second author for inclusion in the synthesis. Additional articles identified in the reference lists of the selected articles were part of the final set of articles reviewed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Inclusion Criteria

The final articles for selection met the following inclusion criteria: (a) evaluation study, (b) report of original quantitative research, (c) adult Black women 18 years or older, (d) a multicomponent intervention designed to address two or more of the targeted outcomes for survivors of violence (i.e., HIV risk [e.g., unprotected intercourse, condom use, substance misuse], violence reduction, mental health, stress, and reproductive health), (e) studies conducted in the United States, (f) included survivors of any form of violence, and (f) published in English language. We did not limit the studies to particular settings or specific time periods.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were eliminated if the intervention studies (a) exclusively focused on men, (b) focused on participants under the age of 18 years, (c) evaluated an intervention with only one component (e.g., home visit only or distributing brochures only), (d) did not evaluate an intervention on the targeted outcomes (e.g., just described recruitment and retention strategies), (e) did not evaluate two or more of the targeted outcomes in combination (i.e., mental health, stress management, safety, HIV risk, and reproductive health outcomes) for women, (f) just described the protocol of the intervention, (g) did not identify the sample as survivors of violence, (h) did not clearly mention Black women being part of the sample, (i) were conducted in non-U.S. settings, and (j) were not published in English language. We also eliminated thesis that could not be accessed. The information collected was summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Multicomponent Interventions.

| Authors | Name of the Intervention | Significance of Outcomes

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violence Reduction/Future Revictimization | Mental Health | Stress | HIV Risk (Sexual HIV Risk and Drug-Related HIV Risk) | Reproductive Health | ||

| Cocozza et al. (2005) | Women Co-occurring Disorder Study Program Sites | NA | + | NA | + | NA |

| Coker et al. (2012) | In Clinic IPV Advocacy Intervention | + | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Dutton et al. (2013) | Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction | NA | + | + | NA | NA |

| Fallot et al. (2011) | Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model | − | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Ghee et al. (2009) | Condensed Seeking Safety Intervention | NA | + | NA | − | NA |

| Gilbert et al. (2006) | Relapse Prevention and Relationship Safety | + | + | NA | + | NA |

| Johnson et al. (2011) | Hoping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment | + | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Joseph et al. (2009) | DC-HOPE Intervention | + | + | NA | NA | NA |

| El-Mohandes et al. (2008) | DC-HOPE Intervention | + | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Kiely et al. (2010) | DC-HOPE Intervention | + | NA | NA | NA | + |

| Mittal et al. (2017) | Support Positive and Healthy Relationships | + | NA | NA | + | NA |

| Nicolaidis et al. (2012) | Community-based Depression Care Program | NA | + | + | NA | NA |

| Rhodes et al. (2015) | Brief Motivational Interviewing Intervention | − | NA | NA | − | NA |

| Rountree et al. (2014) | HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction Intervention | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | Grady Nia Intervention | NA | + | NA | + | NA |

| Zlotnick et al. (2011) | − | + | NA | NA | NA | |

Note. NA = not assessed; + = positive significant findings; − = no significant findings or no significant differences between treatment and control.

All studies were qualitatively evaluated on the basis of their study design, cultural considerations, eligibility regarding violence, details on the intervention and control groups, representativeness of Black survivors, types of sites implementing the interventions, expertise of the facilitators, follow-up periods for outcomes assessment, attrition rates, the outcomes evaluated, and whether the intervention study reported positive outcomes. All included articles were assessed based on the abovementioned criteria by the first author. The two authors discussed the evaluation criteria and resolved any disagreement in the quality of the studies or the assessment method.

Definition of Terms

Survivors of violence

Survivors of violence included those women who experienced physical, sexual, or psychological abuse by anyone (e.g., intimate partner, caregiver, relative, friend, or a stranger).

Culturally informed or a culturally adapted intervention

The intervention was defined as culturally informed or culturally adapted if it used culturally specific materials or symbols (e.g., African proverbs or illustrations), or if the development of the intervention entailed use of cultural theory or existing Black literature, or if formative work was conducted with Black women (Crepaz et al., 2009).

Multicomponent intervention

A multicomponent intervention in this review was defined as an intervention with a combination of multiple intervention components that addressed two or more physical health, mental health, or safety outcomes (i.e., HIV risk, stress, mental health, reproductive health, and future revictimization by violence) for survivors of violence.

Results

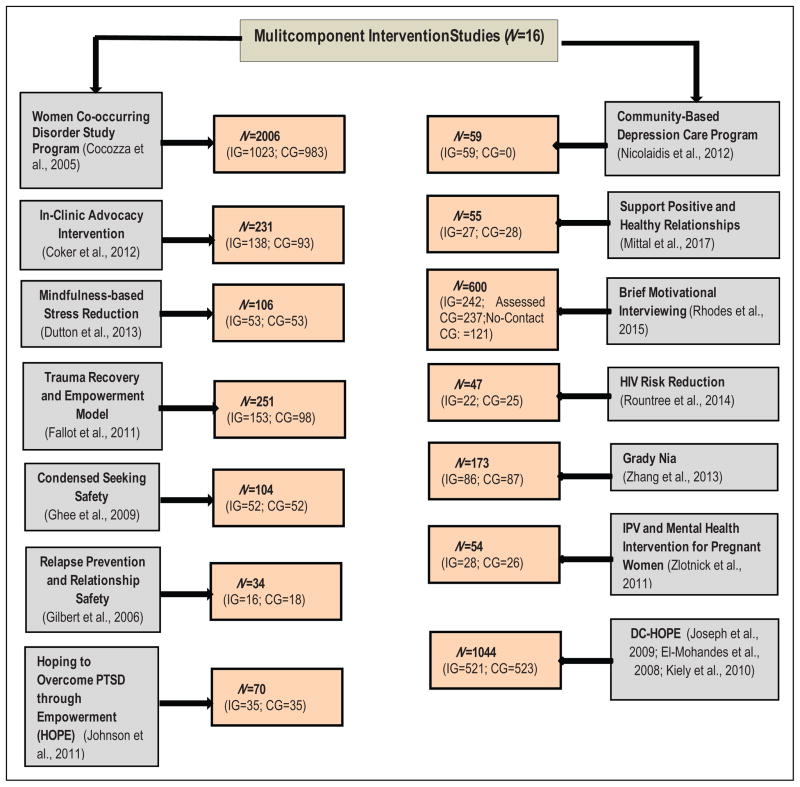

This study identified 16 multicomponent intervention studies that included Black women survivors of violence and addressed at least one or more of the targeted health and safety outcomes commonly associated with violence experiences. The studies did not report on effects of separate components on our targeted health and safety outcomes. However, the studies reported on the effects of the full multicomponent intervention package on improvement in outcomes. Based on the characteristics of the components included in each intervention study that was efficacious in improving outcomes, it was determined that the components of the intervention targeting our multiple outcomes were efficacious. For instance, if a multicomponent intervention study reported improvement in mental health, the mental health component of the intervention was considered efficacious. Online Appendix displays studies evaluating multicomponent interventions for survivors of violence, while Table 1 presents a summary of the interventions including names of the interventions and significance of the targeted outcomes. Figure 2 outlines the studies and the sample sizes. To summarize, the results are organized by the aims of this systematic review:

Figure 2.

Multicomponent intervention studies and sample sizes. IG = intervention group; CG = control group.

Characteristics and Effectiveness of Evidence-Based, Integrated Multicomponent Intervention Studies for Black Women Survivors of Violence

Eleven studies within this review were randomized controlled trials (Dutton, Bermudex, Matas, Majid, & Myers, 2013; El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Ghee, Bolling, & Johnson, 2009; Gilbert et al., 2006; Johnson, Zlotnick, & Perez, 2011; Joseph et al., 2009; Keily et al., 2010; Mittal et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2013; Zolnick et al., 2011), with a control group comprised of standard treatment or usual care. Three studies were quasi-experimental (Cocozza et al., 2005; Coker et al., 2012; Fallot, McHugo, Harris, & Xie, 2011) designs (randomization done at the cluster level and not individual level). The comparison sites delivered usual care services. One study reported pre–post comparison design (Nicolaidis et al., 2012) and one was a nonrandomized trial (Rountree, Bagwell, Theall, McElhaney, & Brown, 2014). For studies that clearly reported follow-up periods, two studies evaluated effects of intervention at the end of treatment, one followed up participants 30 days postintervention, five followed participants from 3 to 6 months, and five up to 12 months. Only one study had a longer follow-up period of 24 months.

The interventions that included future revictimization as an outcome for Black survivors of violence exclusively focused on intervening with IPV survivors, with only three studies reporting interventions or programs for survivors of lifetime physical and/or sexual abuse by any perpetrator (i.e., Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Project [WCDVS]) in primary substance abuse treatment settings (Cocozza et al., 2005), the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) under WCDVS site, in a mental health setting (Fallot et al., 2011), and Condensed Seeking Safety intervention in a residential chemical dependence program (Ghee et al., 2009). The sample sizes for the studies ranged from 16 to 1,023 in the intervention groups and 18 to 983 in the control groups. The survivors of violence were those who reported experiencing physical, sexual, and psychological abuse by an intimate partner or other perpetrators, with the time frame of violence for inclusion ranging from past 90 days to lifetime.

The majority of studies that assessed effectiveness of interventions on mental health focused on depression and PTSD, with a few examining general psychological distress. The efficacy in reproductive health domain was limited to reduction in preterm neonates. Regarding HIV risk, four of the seven studies only assessed drug-related HIV risk of substance abuse, with only one study assessing both drug-related and sexual HIV risk. The remaining two exclusively focused on sexual HIV risk (i.e., frequency of unprotected sex, safe sex conversations, multiple sex partners, HIV knowledge, sexual assertiveness skills, sexual safety planning). Only 6 of the 16 studies were specifically for African American women, testing four interventions/programs overall (DC-HOPE, community-based depression care program for African American IPV survivors, HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction Intervention, and Grady Nia).

Among the targeted outcomes, most of the intervention studies were found to assess mental health, future revictimization, and HIV risk including substance abuse (i.e., multiple sex partners, unprotected sex, sexual assertiveness skills/safe sex conversations, and drug/alcohol abuse). Two studies targeted stress and one reproductive health. The combination of outcomes assessed were violence and mental health in six studies (Coker et al., 2012; El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Fallot et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2011; Joseph et al., 2009; Zlotnick, Capezza, & Parker, 2011), violence, mental health, and HIV risk in one study (Gilbert et al., 2006), mental health and HIV risk in four studies (Cocozza et al., 2005; Ghee et al., 2009; Rountree et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2013), violence and HIV risk in two studies (Mittal et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2015), stress and mental health in two studies (Dutton et al., 2013; Nicolaidis et al., 2012), and violence and reproductive health in one study (Kiely, El-Mohandes, El-Khorazaty, & Gantz, 2010).

The majority of multicomponent intervention studies reviewed reported improvement in our targeted outcomes for survivors of violence. The multicomponent interventions found to report positive outcomes for preventing future revictimization were In Clinic IPV Advocacy (Coker et al., 2012), Relapse Prevention and Relationship Safety (RPRS; Gilbert et al., 2006), Hoping to Overcome PTSD through Empowerment (HOPE; Johnson et al., 2011), DC-HOPE (El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2009; Kiely et al., 2010), and Support Positive and Healthy Relationships (SUPPORT; Mittal et al., 2017). The follow-up periods of these interventions ranged from 1 week to 24 months postintervention. Two interventions (Coker et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2011) reported reduction in IPV scores or lower likelihood of reabuse over the 6-month period. None of the studies reported outcomes that were sustained more than 6 months.

The improvement in mental health outcomes were reported for WCDVS (Cocozza et al., 2005), In Clinic IPV Advocacy (Coker et al., 2012), Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Dutton et al., 2013), TREM (Fallot et al., 2011), Condensed Seeking Safety Intervention (Ghee et al., 2009), RPRS (Gilbert et al., 2006), HOPE (Johnson et al., 2011), DC-HOPE (El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2009), Community-based Depression Care Program (Nicolaidis et al., 2012), Grady Nia (Zhang et al., 2013), and intervention reported in Zlotinck et al. (2011). In some studies, there was noted improvement in specific mental health symptoms but not all. For instance, in comparison to the control group, TREM participants showed significant reduction in anxiety symptoms but not in PTSD or global mental health severity (Fallot et al., 2011). In WCDVS evaluation of program sites, there was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes across sites. The average weighted effect size for intervention group was significant for improved posttraumatic symptoms but not for overall mental health status at 6 months follow-up (Cocozza et al., 2005). In some studies, the impact of intervention was reported only for posttreatment (e.g., Nicolaidis et al., 2012), 30 days posttreatment (Ghee et al., 2009), or 3 months posttreatment (Gilbert et al., 2006). With short follow-up periods, it was difficult to determine whether improvement in mental health outcomes was sustained over a long period of time.

Stress reduction was reported in two multicomponent studies only (Dutton et al., 2013; Nicolaidis et al., 2012). Similar to other outcomes, there were some methodological limitations. For instance, one study did not have a comparison group and the program effects were assessed at the end of intervention with no follow-up (Nicolaidis et al., 2012). Sexual and drug-related HIV risk was addressed in the following multicomponent interventions/programs for survivors of violence: WCDVS (Cocozza et al., 2005), RPRS (Gilbert et al., 2006), SUPPORT (Mittal et al., 2017), HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction (Rountree et al., 2014), and Grady Nia (Zhang et al., 2013). Grady Nia was focused on reducing maladaptive behaviors to cope (e.g., substance use) and promoting adaptive coping strategies (Zhang et al., 2013). It was not specifically designed to reduce HIV risk. The WCDVS program sites reported greater reduction in drug or alcohol use than the control sites (Cocozza et al., 2005). HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction intervention increased HIV knowledge and decreased drug or alcohol use among participants at the end of treatment (Rountree et al., 2014). SUPPORT participants showed a significant decrease in frequency of unprotected sex and an increase in safer sex communications with partners. The increase in safer sex conversations with steady partners were also reported at 3 months follow-up (Mittal et al., 2017). These interventions that reported improvement in overall outcomes had short follow-up periods. Overall, the multicomponent interventions reviewed addressed specific drug-related or sexual HIV risks but did not report reduced risk of HIV in all domains. For instance, in comparison to the control group, RPRS was more effective in reducing binge drinking and use of crack cocaine but not in the use of heroin or marijuana (Gilbert et al., 2006). It was not effective in addressing unprotected sex or condom use but was able to decrease engagement in multiple sexual relationships (Gilbert et al., 2006).

These findings need to be considered in light of some noteworthy limitations. Some studies focusing on future revictimization had low response rates (e.g., less than 50%, Coker et al., 2012), with 22–66% of noncompleters of the intervention. For instance, in an evaluation study of a six-session intervention, 29% of the participants dropped out of the intervention after four or fewer sessions (Ghee et al., 2009). With low retention rates and short follow-up periods, it was difficult to know whether the intervention effects were sustained over a long period of time. In an intervention evaluation study with a long follow-up period (i.e., 24 months), only 30% of the participants completed all follow-up assessments (e.g., Coker et al., 2012). The retention rate was not reported in two studies (Cocozza et al., 2005; Zlotnick et al., 2011). Only a few studies compared the baseline characteristics of those leaving the study or not participating in full sessions with those remaining. And very few interventions (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011) had more than 90% of participants who completed all follow-up sessions.

Overall limitations of multicomponent intervention evaluation studies for survivors of violence in this review were small sample sizes, low response rate or low rate of return, inconsistent participants’ attendance, use of self-reports, non-randomization of some interventions, potential for selection bias, no comparison group, and a lack of credible attention control. For an intervention evaluation, longer follow-up periods are needed to determine whether positive outcomes were sustained. However, most studies in this review had short follow-up periods of 6 months or less. Further, studies had limited generalizability due to exclusive focus on shelter-based samples or specific clinic-based samples (e.g., pregnant women or low-income urban samples). Moreover, lack of attention to contextual challenges survivors faced (e.g., poverty, intergenerational health issues, cumulative stress) was another limiting factor.

Efficacy of Integrated Multicomponent Intervention Strategies on Individual Outcomes

Components of interventions that included future revictimization as an outcome

The common components of integrated interventions that targeted future revictimization were skill building in areas such as negotiation, boundary setting, communication, safety/self-protection, and effective coping with IPV. Some included education on cycle of abuse, consequences of abuse, IPV prevention education, warning signs of violent relationships or immediate danger, and making a safety plan. Interventions also provided linkage to support and services and focused on overall empowerment to improve quality of life. With the exception of TREM (Fallot et al., 2011), all studies assessing future safety focused on IPV. The eligibility criteria for including women in the intervention trial was only IPV (Coker et al., 2012), both IPV and drug/alcohol use (Gilbert et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2015), IPV and sexual risk behavior (Mittal et al., 2017), IPV and PTSD (Johnson et al., 2011), or IPV as one of the risks (i.e., active smoking, depression, environmental tobacco exposure; El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2009; Kiely et al., 2010). TREM (Fallot et al., 2014) participants had a history of physical and/or sexual abuse and a co-occurring mental health and substance abuse problem. The components of effective interventions were individualized needs assessment, safety planning, education, support, and referrals. Trauma education and emphasis on the importance of safety were particularly reported to be critical components of interventions for survivors. Other effective characteristics included cognitive behavioral individualized approaches focusing on addressing areas of dysfunction, immediate needs of safety, and self-care, and overall improvement in quality of life with future goal-setting for safety (Table 1). With the exception of RPRS, the majority of studies reported improvement in overall IPV. It was unclear whether these components were effective for women with certain types of violence histories. The RPRS participants were more likely than control participants to report a decrease in minor physical or sexual IPV, minor and severe psychological IPV, but there were no significant differences between the groups on sexual IPV or injurious IPV outcomes (Gilbert et al., 2006). TREM, the only non-IPV intervention study, did not find significant differences between the intervention and control groups on exposure to interpersonal abuse (Fallot et al., 2011).

The interventions that had positive outcomes for IPV were delivered by an IPV advocate, or an expert with psychology/counseling, or social worker with prior experience working with traumatized populations. Thus, components of efficacious integrated IPV interventions are individualized need-based services with emphasis on safety, assessment of risk, coping skills to deal with trauma, linkage to community resources, and overall improvement in quality of life. Also important is the expertise of the person delivering the intervention and quality assurance of intervention implementation (Coker et al., 2012). Since the only intervention study that included non-IPV participants and assessed for overall exposure to violence as an outcome reported nonsignificance, additional studies are needed to establish evidence base for multicomponent interventions for Black survivors of violence, other than IPV.

Components of interventions that were trauma-focused or included mental health as an outcome

Integrated interventions targeting mental health among survivors require multiple components and a combination of approaches (i.e., individual and groups) based on individual needs, skill building in specific areas of needs including self-care, coping, self-management, and linking participants to community resources. Most integrated interventions efficacious in improving mental health focused on skill-building, self-care or self-management behaviors, linking participants to services based on their needs and education, using a combination of individual and group therapy approaches, with intervention duration ranging from 3 weeks to 6 months (e.g., Coker et al., 2012; Dutton et al., 2013; Ghee et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). With the exception of WCDVS program (Cocozza et al., 2005), all of the studies that reported improvement in mental health included only survivors of IPV (physical, sexual, and psychological abuse). The two studies that included survivors of general physical and sexual abuse reported improvement in some mental health symptoms but not all (Fallot et al., 2011; Ghee et al., 2009). These group-based interventions using cognitive restructuring, providing coping skills training for trauma, or teaching alternate coping skills, group support to facilitate recovery were effective in reducing some mental health symptoms (i.e., anxiety and sexual abuse–related trauma symptoms) but were not effective for global mental health symptoms, PTSD, or overall trauma symptoms (e.g., Fallot et al., 2011; Ghee et al., 2009). One individual-based intervention using interpersonal psychotherapy approach, enhancing social support, and teaching self-management skills did not impact major depressive episode or PTSD during pregnancy but had larger effect in reducing PTSD from pregnancy to postpartum (Zlotnick et al., 2011). Thus, some interventions were only efficacious in improving specific symptoms of mental health (e.g., PTSD only). In a study, there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in improved mental health. This was attributed to small sample size of 25 in the intervention and 25 in the control group since the attrition in both groups was unusually high. This was a shelter-based sample, and location of the intervention was reported as a possible factor in attrition rate because of the stigma associated with experiencing IPV (Rountree et al., 2014). In some studies, shortening the sessions or the intervention (e.g., 5–6 sessions only) did not result in overall trauma reduction or improving global mental health symptoms (Fallot et al., 2011; Ghee et al., 2009). Other researchers, however, recommended shortening number of sessions or duration of the intervention to accommodate the multiple demands on women’s lives and potentially using technology to deliver some of the components (Rountree et al., 2014).

Components of interventions that included HIV risk as an outcome

The components of interventions reducing HIV risk behaviors among survivors included education on STDs, HIV/AIDs, healthy lifestyle, self-protection, and healthy relationships and teaching self-regulatory skills. Reducing drug-related HIV risk among survivors of violence needed integrated mental health counseling and trauma services in substance abuse programs, skill-building in adaptive coping styles to deal with trauma, strengths-based assessments, and need-based intervention plans (Table 1). Almost all interventions included group-based sessions, ranging from 6 weeks to 10 weeks. With the exception of Condensed Seeking Safety Intervention (Ghee et al., 2009), all multicomponent interventions addressing HIV risk focused on survivors of IPV (Online Appendix). The Brief Motivational Interviewing intervention (20–30 min) with telephone booster at 10 days was not effective in reducing drug/alcohol-related HIV risk of heavy drinking (Rhodes et al., 2015). The RPRS intervention including participants in substance abuse treatment program was successful in reducing use of specific drugs but not others and in reducing sexual HIV risk behavior of multiple sexual partners but not nonuse of condoms (Gilbert et al., 2006). The Condensed Seeking Safety intervention, which included survivors of general interpersonal abuse, only addressed drug-related HIV risk. The intervention was not found to be effective in reducing relapse 30 days after treatment ended (Ghee et al., 2009).

Components of interventions that included stress management as an outcome

The intervention that was successful in reducing stress among survivors used the MBSR protocol (Dutton et al., 2013). The second intervention that has stress as one of the outcomes was a multicomponent depression care program including case management, education, self-management components, and linking participants to resources. However, there were no noted significant reductions in stress (Nicolaidis et al., 2012). Both these multicomponent interventions focused on survivors of IPV.

Components of interventions that included reproductive health issues as outcomes

Only the DC-HOPE intervention study (Kiely et al., 2010) included a reproductive health component and was effective in improving pregnancy outcomes in terms of reduced preterm neonates. The intervention was an individualized intervention including individual counseling, safety behaviors, education on IPV, providing information about community resources, mood management of depression, increasing pleasurable activities, and increasing positive social interactions. The focus of this intervention was also survivors of IPV (Kiely et al., 2010).

Discussion

This review examined research on multicomponent interventions that effectively addressed two or more widely known outcomes of violence reported among Black women (i.e., mental health, chronic stress, risk for future revictimization, HIV risk, and reproductive health issues; Moffitt & Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank, 2013; Sabri et al., 2013; Salam et al., 2006; Stockman et al., 2013; Sundermann et al., 2013). Components of multicomponent interventions were considered efficacious if they led to improvement in the targeted outcomes. For instance, if a multicomponent intervention study reported reduction in violence, the violence component of that intervention was considered efficacious for reducing violence. Only 11 studies were identified that used randomized control methods to evaluate efficacy of multicomponent interventions to address multiple outcomes among Black survivors of violence. Thus, the body of evidence on interventions for Black women survivors of violence that address their multiple health issues is minimal. The studies evaluated interventions that differed in content, format, settings, number of sessions offered, and inclusion criteria. The measures used to assess outcomes also differed across studies. Further, variations in target samples for intervention (e.g., pregnant women only) made it difficult to determine whether the components of interventions would be effective for all Black women survivors of violence. All studies included in the review used self-reports to assess outcomes, which is subject to recall and social desirability bias. Further, the follow-up assessment time periods were short. The outcomes of the interventions should be assessed following completion of the intervention and at multiple time points to capture both short-term and long-term effects of intervention (Sprague et al., 2016).

Components of efficacious interventions for violence were risk assessments, safety plans, coping skills training, addressing survivors’ concrete needs (e.g., legal assistance), providing linkage to community resources, and empowering survivors to improve overall quality of life. Almost all studies with violence reduction or future revictimization as one of the two outcomes focused on IPV, indicating a gap in evidence for interventions addressing other forms or multiple forms of violence among Black women. Only one intervention study (Dutton et al., 2013; MBSR) mentioned that although women were recruited based on lifetime IPV, all participants had experienced multiple lifetime traumas across the lifespan. The MBSR intervention reduced stress and improved mental health outcomes for survivors (Dutton et al., 2013). The study did not assess future revictimization as an outcome. Thus, there is need to establish evidence base for multicomponent interventions that address violence and associated health issues among Black women with multiple violence experiences.

Only two studies demonstrated efficacy in promoting stress reduction and reproductive health. Thus, additional, evidence-based, multicomponent interventions are needed to reduce symptoms of stress and to improve reproductive health outcomes among Black survivors of violence. Multicomponent interventions that reduced HIV risk among survivors included education on HIV/STIs, healthy lifestyle, self-protection, and self-regulatory skill-building strategies for sexual HIV risk. To address drug-related HIV risk among survivors, the needed components included strengths-based assessments, mental health counseling, skill-building in coping, and need-based intervention plans. In the existing literature on interventions exclusively focusing on HIV risk reduction among Black women, efficacious interventions have been found to be culture-specific; empowerment based; delivered by women; promote self-efficacy, relationship communication, and assertiveness; and include skill building in correct condom use and negotiation of safer sex (Crepaz et al., 2009).

Efficacious interventions for mental health included components such as psychoeducation, skill-building exercises in specific areas (e.g., self-care and coping with trauma), and linking participants to needed resources. Strategies used to reduce trauma-related distress were derived from empowerment and social cognitive theories (e.g., RPRS; Gilbert et al., 2006; HOPE; Johnson et al., 2011) and included gender-focused, Afrocentric empowering practices (Grady Nia; Zhang et al., 2013). Our research did not identify a trauma-focused intervention that addressed mental health among Black survivors of interpersonal abuse other than IPV. In another review, research testing trauma-focused interventions for other forms of abuse (e.g., rape and sexual violence not limited to IPV) have shown effectiveness of certain types of cognitive and behavioral interventions (cognitive-processing therapy, prolonged exposure, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) in reducing depression, PTSD, and anxiety symptoms among survivors (Regehr, Alaggia, Dennis, Pitts, & Saini, 2013). These interventions, however, have been tested on primarily White samples. Evidence shows that while some trauma-focused interventions may be useful with certain populations, they may in fact increase symptoms in other groups of victims (Regehr et al., 2013). Thus, additional research is needed to establish evidence for trauma-focused intervention components that would resonate with Black survivors of IPV and other forms of interpersonal abuse.

Very few intervention studies provided information suggesting that they were culturally informed, infusing cultural values and strengths into interventions or accounting for contextual factors such as minority racial status, low socioeconomic status, and stressful life events. Four interventions had less than 50% of the Black women in the sample (Cocozza et al., 2005; Ghee et al., 2009; Gilbert et al., 2006; Zlotnick et al., 2011). Very few interventions exclusively focused on Black women and those too did not take into account diversity among these Black women or whether cultural background may be a moderating factor in interventions. Further, there was inadequate attention to multiple and interrelated lifetime causes of health and safety outcomes. The DC-HOPE intervention combined elements of social-ecological, transtheoretical model, and cognitive behavioral treatment to address multiple risks for poor reproductive health outcomes among Black women, but the intervention exclusively focused on pregnant Black women (Katz et al., 2008). Also, the study did not report any culturally specific components that were incorporated in the intervention.

One study, evaluating the effects of Grady Nia (Zhang et al., 2013), described the intervention as a culturally competent empowerment-based intervention for Black women. The authors highlighted the important role of culture in women’s vulnerability to traumatic life experiences, subsequent reactions to traumatic events, and responses to trauma interventions (Zhang et al., 2013). For interventions to be culturally competent for Black women, interventions need to account for differences in social class backgrounds, since needs, strengths, and responses to life stressors vary among low-, middle-, and high-income Black families (Kaslow et al., 2006). Women should be engaged in the development of interventions, something that was not evident in the studies we reviewed. Important factors to consider in development of interventions for abused Black women include country of origin; region of the country Black women belong to; and whether or not they are residing in urban, suburban, or rural areas (Kaslow et al., 2006).

Although some multicomponent interventions in this review appeared promising in addressing at least two outcomes for Black survivors, particularly revictimization and mental health (HOPE, DC-HOPE, RPRS, In-Clinic Advocacy), the interventions focused on clinic-based samples (e.g., drug-using or pregnant women) and those with IPV only. Only two interventions addressed revictimization and sexual HIV risk, with focus on IPV survivors. There is a clear gap in the evidence for multicomponent interventions aimed at reducing stress and promoting reproductive health among survivors along with other issues such as revictimization and mental health. Further, there is a gap in the literature on evidence-based multicomponent interventions for addressing complex co-occurring needs of survivors of all forms of violence (not just IPV), particularly those in nonclinical settings. Moreover, the limitations in design and methods of existing multicomponent interventions highlight the need for rigorously evaluated interventions for Black survivors of violence. There is a need for comprehensive multicomponent trauma-focused interventions based on a culturally responsive framework that account for diversity among Black survivors and include strategies that address their complex and co-occurring health and safety needs.

Conclusion, Implications, and Limitations

This review highlighted the need for establishing an evidence base for multicomponent interventions that target multiple health care and safety needs of Black survivors of violence. Although the majority of the interventions in the review had components that addressed trauma/mental health, this was not always reported in studies that focused on other health issues such as HIV risk or reproductive health among survivors. Addressing trauma symptoms has been shown to address multiple health and safety concerns among survivors such as sexual and drug-related HIV risk behaviors, and future revictimization (Gilbert et al., 2015). The intervention components for Black survivors of violence must be culturally specific and empowerment based. Based on this review, components that could target multiple health and safety risks would be strengths-based culturally responsive needs assessments, individualized intervention plans that address concrete needs, a safe environment for survivors, linkages to community resources, skill building to cope with trauma and other life stressors, stress management and self-care, and education about multiple health risks associated with violence (e.g., HIV/STI, PTSD). Research is needed to develop interventions that meet the highest standards for evidence-based interventions for Black survivors with multiple and complex needs.

The studies included in this review have several limitations that may have affected the results. First, not all studies were exclusively focused on Black populations or accounted for diversity among Blacks. This precludes generalizabilty of the findings to Black survivors from all ethnicities in the United States. Second, the outcomes of the interventions in the review may have varied based on the types of violence experienced (e.g., types of IPV), recency of violence, or other ongoing stressors in women’s lives. Third, the review did not include research published in other languages. However, despite these limitations, the findings are informative for future researchers, policy makers, and practitioners planning to design and implement multicomponent interventions that address survivors’ multifaceted needs. Such integrated interventions call for collaboration and coordination of services among professionals from multiple disciplines and agencies. Examples of such agencies include mental health agencies, substance abuse programs, rape victim or domestic violence programs, HIV care clinics, and clinics providing reproductive health-care services to women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development (K99HD082350).

Biographies

Bushra Sabri is a research associate faculty member at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing and Adjunct faculty at Brescia University, Owensboro, and Institute for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research. She has extensive cross-cultural and cross-national experiences in health care and social service settings. She has been involved in several funded research projects focusing on interpersonal violence across the lifespan and health outcomes of violence. She is currently supported by NICHD (K99HD082350). Her research focuses on factors related to risk of HIV and reproductive and sexual health problems among women with lifetime cumulative trauma, role of physiological stress responses in coping and adaptation to traumatic life events, and biopsychosocial approach to development of trauma informed culturally tailored interventions for at-risk women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Andrea Gielen is a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy. Her research focuses on using behavioral sciences theories and methods to conduct needs assessment research, build interventions based on those findings, and conduct both intervention trials and translational research to disseminate interventions. She has led a number of federally funded intervention trials, including CDC, NICHD, and MCHB-funded studies of injury and violence prevention interventions delivered in community settings, well child clinics, and emergency departments. Most of her work has addressed prevention needs of low-income, urban families in the areas of domestic violence, home and motor vehicle injuries. She has published more than 180 peer-reviewed articles.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of PTSD in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:81–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Female victims of violence. 2009 Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvv.pdf.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV in women. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/13_243567_green_aag-a.pdf.

- Cocozza JJ, Jackson EW, Morrissey JP, Reed BG, Fallot R, Banks S. Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: Program-level effects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Le B, Crawford TN, Flerx VC. Effect of an in-clinic IPV advocate intervention to increase help seeking, reduce violence, and improve well-being. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:118–131. doi: 10.1177/1077801212437908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay LS, … O’Leary A. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey DE, Humphreys JC, Rankin SH, Lee KA. An exploration of lifetime trauma exposure in pregnant low income African American women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15:410–418. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Bermudex D, Matas A, Majid H, Myers NL. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low-income, predominantly African American women with PTSD and a history of intimate partner violence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mohandes AAE, Kiely M, Joseph JG, Subramanian S, Johnson AA, Blake SM, … El-Khorazaty MN. An intervention to improve post-partum outcomes in African American mothers. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;112:611–620. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181834b10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, McHugo GJ, Harris M, Xie H. The trauma recovery and empowerment model: A quasi-experimental effectiveness study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2011;7:74–89. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2011.566056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghee AC, Bolling LC, Johnson CS. The efficacy of a condensed seeking safety intervention for women in residential chemical dependence treatment at 30 days’ posttreatment. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2009;18:475–488. doi: 10.1080/10538710903183287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Manuel J, Wu E, Go H, … Golder S, … Sanders G. An integrated relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention for women on methadone: Testing short-term effects on intimate partner violence and substance abuse. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:657–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, Stockman J, Terlikbayeva A, Wyatt G. Targeting the SAVA (substance abuse, violence, and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: A global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2015;69:S118–S126. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women’s shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:542–551. doi: 10.1037/a0023822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JG, El-Mohandes AAE, Kiely M, El-Khorazaty N, Gantz MG, Johnson AA, … Subramanian S. Reducing psychosocial and behavioral pregnancy risk factors: Results of a randomized clinical trial among high-risk pregnant African American women. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1053–1061. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Thorn SL, Paranjape A. Interventions for abused African-American women and their children. In: Gullota Thomas P, Walbergm Herbert J, Weissberg Roger P., editors. Interpersonal violence in the African American community: Evidence-based prevention and treatment practices. Chapter 3. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Katz KS, Blake SM, Milligan RA, Sharps PW, White DB, Rodan MF, Rossi M, Murray KB. The design, implementation and acceptability of an integrated intervention to address multiple behavioral and psychosocial risk factors among pregnant African American women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2008;8(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, El-Khorazaty N, Gantz MG. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;115:273–283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Goldsmith R. Links between exposure to violence and HIV-infection: Implications for substance abuse treatment with women. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2008;18:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzche PC, Ioannidis JPA, … Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Medicine. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Ullman SE. The impact of multiple traumatic victimization on disclosure and coping mechanisms for Black women. Feminist Criminology. 2013;8:295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J, Wight M, Heerden AV, Rochat TJ. Intimate partner violence, HIV, and mental health: A triple epidemic of global proportions. International Review of Psychiatry. 2017;28:452–463. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2016.1217829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Thevenet-Morrison K, Landau J, Cai X, Gibson L, Schroeder A, … Carey MP. An integrated HIV risk reduction intervention for women with a history of intimate partner violence: Pilot test results. AIDS Behavior. 2017;21:2219–2232. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1427-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE The Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank. Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress biology research join forces. Developmental Psychopathology. 2013;25:1–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Wahab S, Trimble J, Mejia A, Mitchell SR, Raymaker D, … Waters AS. The interconnections project: Development and evaluation of a community-based depression program for African American violence survivors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;28:530–538. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2270-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez S, Johnson DM. PTSD compromises battered women’s future safety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:635–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr C, Alaggia R, Dennis J, Pitts A, Saini M. Interventions to reduce distress in adult victims of rape and sexual violence: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2013;23:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Rodgers M, Sommers M, Hanlon A, Chittams J, Doyle A, … Crits-Christoph P. Brief motivational intervention for intimate partner violence and heavy drinking in the emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314:466–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree MA, Bagwell M, Theall K, McElhaney C, Brown A. Lessons learned: Exploratory study of a HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for African American women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2014;7:24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Stockman JK, Betrand D, Campbell DW, Gloria GB, Campbell JC. Victimization experiences, substance misuse and mental health problems in relation to risk for lethality among African American and African Caribbean women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:3223–3241. doi: 10.1177/0886260513496902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam A, Alim A, Noguchi T. Spousal abuse against women and its consequences on reproductive health: A study in the urban slums in Bangladesh. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague S, McKay P, Madden K, Scott T, Tikasz D, Slobogean GP, Bhandari M. Outcome measures for evaluating intimate partner violence programs within clinic settings: A systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1524838016641667. Published online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implementation Science. 2014;9:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Draughon JE, Sabri B, Anderson JC, Bertrand D, … Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk factors among African-American and African-Caribbean women in clinic-based settings. AIDS Care. 2013;25:472–480. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CM, Bybee DI. Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:43–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann JM, Chu AT, DePrince AP. Cumulative violence exposure, emotional non-acceptance, and mental health symptoms in a community sample of women. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2013;14:69–83. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2012.710186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Carey D, Prewitt K, Romero E, Richards M, Velsor-Friedrich B. African-American youth and exposure to community violence: Supporting change from the inside. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology. 2012;4:54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tutty L, Bidgood B, Rothery M. Support groups for battered women: Research on their efficacy. Journal of Family Violence. 1993;8:325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women: Scientific review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:589–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver TL, Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Resnick HS, Noursi S. Identifying and intervening with substance-using women exposed to intimate partner violence: Phenomenology, comorbidities, and integrated approaches within primary care and other agency settings. Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;24:51–56. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Neelarambam K, Schwenke TJ, Rhodes MN, Pittman DM, Kaslow NJ. Mediators of a culturally-sensitive intervention for suicidal African American women. Journal of Clinical Psychology Medical Settings. 2013;20:401–414. doi: 10.1007/s10880-013-9373-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Capezza NM, Parker D. An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: A pilot study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2011;14:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.