Abstract

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders present in all ethnic groups. We investigated the frequency of consanguinity among parents of newborns with IEM diagnosed by neonatal screening.

Data were obtained from 15 years of expanded newborn screening for selected IEM with autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, a national screening program of newborns covering the period from 2002 until April 2017. Among the 838,675 newborns from Denmark, the Faroe Islands and Greenland, a total of 196 newborns had an IEM of whom 155 from Denmark were included in this study. These results were crosschecked against medical records. Information on consanguinity was extracted from medical records and telephone contact with the families.

Among ethnic Danes, two cases of consanguinity were identified in 93 families (2.15%). Among ethnic minorities there were 20 cases of consanguinity among 33 families (60.6%). Consequently, consanguinity was 28.2 times more frequent among descendants of other geographic place of origin than Denmark. The frequency of consanguinity was conspicuously high among children of Pakistani, Afghan, Turkish and Arab origin (71.4%). The overall frequency of IEM was 25.5 times higher among children of Pakistani, Turkish, Afghan and Arab origin compared to ethnic Danish children (5.35:10,000 v 0.21:10,000). The frequency of IEM was 30-fold and 50-fold higher among Pakistanis (6.5:10,000) and Afghans (10.6:10,000), respectively, compared to ethnic Danish children.

The data indicate a strong association between consanguinity and IEM. These figures could be useful to health professionals providing antenatal, pediatric, and clinical genetic services.

Keywords: Inherited metabolic disease, Consanguinity, Ethnic group, Neonatal screening

1. Introduction

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) are a heterogeneous group of rare genetic disorders that are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in children and adults. The outcome of many IEM is directly related to how early correct diagnoses are made and appropriate treatment instituted. Most of the IEM are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, and the majority of cases are due to enzymatic defects arising from aberrations in single genes. Autosomal recessive IEM are characterized by their varying frequencies in different ethnic groups, as a result of natural selection, genetic drift, and large-scale migration from countries where consanguinity is favored [1]. This is apparent in a somewhat ethnically diverse country as Denmark and other Western societies, where migration from countries with tradition for consanguineous unions has been a significant demographic feature [2], thus, having an impact on the patient profile of medical genetics clinics in recipient countries [3], [4].

To determine the genetic basis of IEM in Denmark, we undertook a national study and investigated the frequency of IEM among ethnic minorities and the ethnic Danish population and whether there is an association between the frequency of consanguinity and the prevalence of IEM with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and patients

This study was retrospectively designed in Department of Clinical Genetics, Rigshospitalet. Based on results from the National Danish expanded neonatal screening for selected IEM that started in 2002 [5], the medical records of all neonates between 2002 to April 2017 with a true positive result for an IEM were reviewed for consanguinity. In cases where the information stated in the medical records was not adequate, additional information was gathered through telephone contact with the parents of the affected children.

The selection of IEM was based on criteria such as national disease frequencies; availability of effective treatment, severity of disorder; benefit of early treatment; prevention of early death; no clinical signs at birth; detectability by an easy and precise screening method (for further details, see Lund et al.) [5].

Parental consanguinity in our study was defined according to the definition applied in clinical genetics as a union between two individuals related as second cousins or closer [6].

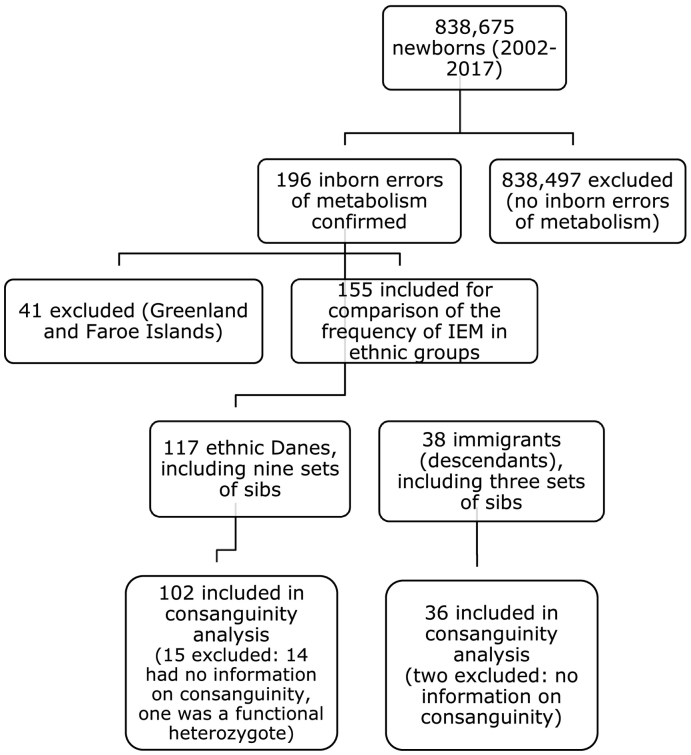

Fig. 1 shows a flow diagram of inclusion of cases. 196 neonates were reported with an IEM. Of these, 41 referred to the department from Greenland and The Faroe Islands were excluded. These are relatively small and homogenous populations, and we wanted to establish, in a population of significant size and ethnic diversity, if there was any significant difference in the frequency of consanguinity between ethnic Danes and ethnic minorities with an IEM with a recessive mode of inheritance. The remaining 155 patients comprised 117 ethnic Danes, including nine sets of sibs, and 38, including three sets of sibs, with origin from primarily Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Middle East. Of the 155 patients, information about consanguinity could not be obtained in 16 patients, and one was a functional heterozygote (both mutations were on the same chromosome inherited from his father). Nonetheless, the 16 patients were included in the calculation of the prevalence of disease since the diagnosis and ethnicity were known. However, among these same 16 patients, 14 in the ethnic Danish patient group and two in the ethnic minority groups were not included in the calculation of consanguinity. Knowing their IEM diagnosis, omitting these patients would have given a false impression of disease frequencies of IEM in the different ethnic groups.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of steps in analysis.

When calculating the prevalence of disease and consanguinity in the ethnic groups, more than one case of the same disease in a sibship were counted as a single case.

We gathered information related to patient's name and personal identification number, nationality/ethnicity (by maternal country of birth), diagnosis, mutation and family history – whether the neonate was born to consanguineous parents or not and previous history of genetically affected sibs.

Demographic and statistical data on ethnic groups were gathered from the Danish Statistics Bureau, Statistics Denmark. We collected data on the number of inhabitants in Denmark (Danish citizenship) at April 1, 2017, number of inhabitants in Denmark defined as ethnic Danes, i.e. inhabitants with Denmark as country of origin at April 1, 2017, and number of Pakistani, Turkish, Afghan and Arab (Arab = Jordanians, Somalis, Palestinians) descendants in Denmark with Danish and foreign citizenship at April 1, 2017.

Inclusion criteria were a confirmed diagnosis of an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder, address in Denmark and knowledge of family history (± consanguinity).

2.2. The Danish Civil Registration System (CRS)

The Danish healthcare system is publically funded. Data from hospitals are gathered in public registries linked with a unique personal identification number assigned to all inhabitants since 1968. The Danish Civil Registration System [7] is an administrative system containing individual information on the unique personal identification number, name, gender, date of birth, citizenship, identity of parents, place of residence, civil status, immigration and/or death. The CRS number is assigned to all persons with residential location in Denmark at birth or immigration.

2.3. Statistical concepts

Immigrants, descendants and country of origin are statistical concepts based on family relations, citizenship and country of birth. Since all the neonates in the ethnic minority groups were born in Denmark they are, according to the classification in Statistics Denmark, defined as descendants [8]. Statistics Denmark provides information on the number of immigrants and their descendants, their age, sex, citizenship, place of birth, country of origin and geographical distribution. The statistics are based on data obtained from the CRS.

2.4. Ethnicity

A number of different indicators can be applied when measuring ethnicity, e.g. country of birth, maternal/paternal country of birth, principal language at home, native language, citizenship of the person in question, and citizenship of the parents. We considered country of birth as an acceptable approximation for ethnicity. We defined ethnicity of the child by the mother's country of birth, similar to the definition used by Statistics Denmark. Thus, all births to women born outside of Denmark were referred to as children of the mother's country of birth, and children born to mothers who themselves were born in Denmark as ethnic Danish.

3. Results

During the 15 years succeeding the introduction of the National Danish expanded neonatal screening for selected IEM, 838,675 children were born in Denmark, Greenland and Faroe Islands. By April 2017, IEM with autosomal recessive mode of inheritance affecting the major biochemical areas of amino acid, organic acid, and carbohydrate metabolism had been diagnosed in 196 children born during this period. Table 1 shows the cases of IEM detected in ethnic Danes and ethnic minorities. All the patients are included, including cases among sibs.

Table 1.

Diseases among ethnic Danes (n = 117) and ethnic minorities (n = 38) born between January 2002 and April 2017.

| Diagnosis | D (%) | M | DF | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argininosuccinic acidemia | 4 (3.4) | 0 | ~ 1/100,000 | #207900 |

| Biotinidase deficiency | 13 (11) | 7 (18.4) | ~ 1/75,000 | #253260 |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase IA deficiency | 0 | 1 (2.6) | Unknown | #600528 |

| Carnitine transporter deficiency | 3 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | ~ 1/100,000 | #212140 |

| Citrullinemia | 0 | 1 (2.6) | Unknown | #215700 |

| Galactosemia | 1 (0.85) | 0 | Unknown | #230400 |

| Glutaric acidemia type 1 | 7 (5.9) | 3 (7.9) | Unknown | #231670 |

| HMG-CoA synthase deficiency | 0 | 1 (2.6) | Unknown | #605911 |

| Holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency | 2 (1.7) | 0 | ~ 1/100,000 | #253270 |

| Isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 1 (0.85) | 0 | Unknown | #611283 |

| Isovaleric acidemia | 1 (0.85) | 0 | Unknown | #243500 |

| Long-chain hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 3 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | ~ 1/75,000 | #609016 |

| Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 68 (58) | 14 (36.8) | ~ 1/10,000 | #201450 |

| 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency | 6 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) | Unknown | #210200 |

| 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency | 0 | 1 (2.6) | Unknown | #250950 |

| Methylmalonic acidemia | 2 (1.7) | 3 (7.9) | ~ 1/30,000 | #251000 |

| Propionic acidemia | 2 (1.7) | 0 | ~ 1/200,000 | #606054 |

| Tyrosinemia type 1 | 1 (0.85) | 1 (2.6) | ~ 1/100,000 | #276700 |

| Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 3 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | ~ 1/75,000 | #201475 |

| Total | 117 (100) | 38 (100) |

D: number of patients in the Danish group (%).

M: number of patients in the ethnic minority group (%).

DF: disease frequency.

Sibs: nine cases of IEM among sibs in the Danish group (eight MCADD, one 3-MCC deficiency), and three cases of IEM among sibs in the ethnic minority group (two MCADD, one Glutaric acidemia type 1).

One case of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency in the Danish group was functionally a heterozygote.

In the ethnic Danish population (Table 1) nine cases of disease were found among sibs. Additionally, one patient was a true screen positive for an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder (holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency), but further examination by the use of molecular genetic analysis showed that the patient was functionally a heterozygote, i.e. both mutations were on the same chromosome inherited from his father. These ten cases were excluded. The remaining 107 patients represented 107 families with autosomal recessive disease.

Among ethnic minorities (Table 1), there were three cases of disease among sibs, which were excluded. The remaining 35 patients represented 35 families with autosomal recessive disease.

Table 1 shows that medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) was the most frequently found IEM among ethnic Danes as well as ethnic minorities. Among Danes 58% had MCADD; among ethnic minorities the frequency was 36.8%.

Table 2 shows the frequency of consanguinity in the different ethnic groups. Of the 33 sets of parents from ethnic minorities, about whom information about consanguinity was available, 20 were consanguineous, i.e. 60.6%. Among Danes, two cases of consanguinity were found among 93 families, i.e. 2.15%. The most popular form of consanguineous union was first cousin marriage, where the coefficient of inbreeding (F) equals 0.0625 for first cousin offspring. Among ethnic minorities, the 20 cases of consanguinity identified, one was a double first-cousin marriage (F = 0.125), 13 were first cousin unions, and six patients were progeny of second cousin unions (F = 0.0156). The two cases of consanguinity identified among ethnic Danes were second cousins (F = 0.0156). The prevalence of consanguinity was 28.2 times more frequent among ethnic minorities than among ethnic Danes. The frequency of consanguinity was conspicuously high among children of Pakistani, Afghan, Turkish and Arab origin (71.4%).

Table 2.

Consanguinity among ethnic minorities.

| Ethnicity | n | Excluded | Couple | Consanguineous couple | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistani | 7 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 100.0 |

| Arab | 8 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 28.6 |

| Turkish | 10 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 90.0 |

| Afghan | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 60.0 |

| Total | 33 | 2 | 28 | 20 | 71.4 |

| Other | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 38 | 2 | 33 | 20 | 60.6 |

Ethnicity: ethnic group, by maternal country of birth.

n: total number of patients in the group.

Excluded: patients with no available information about consanguinity.

Couple: sets of parents/marriages.

Consanguineous couple: number of consanguineous marriages.

%: percentage of consanguineous marriages.

Sibs: three sets of sibs in the Afghan group.

Other: Iceland, Great Britain, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Lithuania, Switzerland.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of IEM in the different ethnic groups. More than one case of disease among sibs were counted as a single case. In addition to a high frequency of consanguinity, the prevalence of disease was also significantly higher in ethnic minorities than in ethnic Danes. The frequency of IEM among Danes and ethnic minorities compared to the overall number of Danes and descendants of the above-mentioned ethnic groups were 0.21/10,000 and 5.35/10,000, respectively. As a result, the frequency of autosomal recessive metabolic disorders was 25.5 times higher among children of Pakistani, Turkish, Afghan and Arab origin than among ethnic Danes.

Table 3.

Prevalence of inborn errors of metabolism in the ethnic groups.

| Ethnicity | n | Number of people in Denmarka | Illness per 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistani | 7 | 10,775 | 6.5 |

| Arab | 8 | 10,446 | 7.65 |

| Turkish | 10 | 30,101 | 3.32 |

| Afghan | 5 | 4695 | 10.64 |

| Total | 30 | 56,017 | 5.35 |

| Other | 5 | 10,241 | 4.88 |

| Danish | 107 | 5,007,197 | 0.21 |

| Total | 142 | 5,073,455 | 0.28 |

Ethnic group: the patients are divided in ethnic groups based on information from the medical records concerning country of origin (mothers country of birth) and, if necessary, telephone conversations with the parents of the affected children. The patients' citizenship is unknown. Consequently, there can be a discrepancy in the information in this paper and the figures from Statistics Denmark.

Excluded: patients with no autosomal recessive disease and sibs.

Patients: only patients with an autosomal recessive disease are included, regardless of whether the degree of relationship between the parents is unknown. More than one case of disease in a sibship are counted as a single case.

Other: Iceland, Great Britain, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Lithuania, and Switzerland.

Source: the Danish Statistics Bureau, Statistics Denmark, April 1, 2017 (2017Q1).

4. Discussion

On April 1st, 2017, immigrants and their descendants represented 12.9% of the total population in Denmark [9]. A large part of these, 8.3%, have origin from countries where consanguineous unions are common [2]. Additionally, figures from the latest population projection show that the proportion of descendants has significantly increased [9]. In the study, consanguineous unions were found to be more frequent among people from Pakistan, Turkey and Afghanistan. These are countries, where consanguineous unions are common, and they represent some of the largest ethnic minority groups in Denmark [2].

This is the largest report of IEM in the offspring of consanguineous unions in Denmark. Although the nationwide neonatal screening for IEM is limited to selected disorders, it is important to remember that IEM are a heterogeneous group of rare genetic disorders and that the total number of patients in the study diagnosed with an IEM is relatively high.

The high frequency of MCADD is, especially for the Danish group (58.0%), not a striking observation given that MCADD is the most prevalent non-PKU congenital metabolic disorder in Western countries [10]. Moreover, increased frequencies of mutations have been found following the implementation of neonatal screening [5], [11].

Compared to the ethnic Danish population, the prevalence of autosomal recessive IEM is conspicuously high among ethnic minorities in the study (Table 3). The findings show a highly significant association between consanguinity and IEM. This association with consanguinity is predictable since all cases of IEM in the study have an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, and migrants from countries where consanguinity is common tend to preserve traditional patterns of marriage [12], [13].

The high proportion of Pakistani, Turkish, Afghan and Arab patients might be the result of the high rate of parental consanguinity. Although control for medical and sociodemographic variables, e.g. maternal age, body mass index, occupation, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, nutrition, parity, medical problems during pregnancy could have been instructive, it is highly unlikely that most of these variables would increase the frequency of a disease with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance [6], [14].

Some well-investigated studies on risk factors for congenital anomalies that also controlled for non-genetic variables have demonstrated a highly significant association between consanguinity and congenital anomalies. These studies had contemporary control groups and were of sufficient size to achieve significance in comparisons between the offspring of consanguineous and those of non-consanguineous unions. In a Norwegian study [15], the proportion of congenital anomalies in children of Pakistani origin born to first cousins that could be attributed to consanguinity was 28%, similar to what was reported from a UK study (31%) [16]. The Norwegian and the UK study reported an adjusted relative risk for congenital anomaly of 2.15 and 2.19, respectively, for children of Pakistani origin who were the product of a first cousin union. The Danish Pakistani community merits particular attention. Many studies have identified consanguinity as a causal factor for the elevated rates of congenital anomalies among some ethnic minorities, particularly the Pakistani community. Specifically for IEM, another prospective study on births in Birmingham during the 1980s concluded that if the tradition of consanguineous marriage was abandoned by the Pakistani community, a 60% reduction in deaths and severe morbidity would be achieved [17]. An associated study further reported that the overall prevalence of IEM in UK Pakistani children was ten-fold higher than in children of European heritage, among whom parental consanguinity was estimated to be 0.2% [1]. Comparing countries separately, our findings show that children of Pakistani origin had the second highest prevalence of IEM, and the highest proportion of consanguinity. Consequently, consanguinity was 46.5 times more frequent among Pakistani descendants than among ethnic Danes (2.15%). The prevalence of IEM among Pakistani descendants was 6.5/10,000 (Table 3). As a result, the frequency of autosomal recessive metabolic disorders was 31 times higher among children of Pakistani origin than among ethnic Danes (0.21/10,000).

A direct comparison between the children of Pakistani and Turkish origin show that the prevalence of IEM is significantly higher among children of Pakistani origin. As in the Pakistani group, almost all the children of Turkish origin had consanguineous parents. However, Turks and their descendants comprise the largest minority group in Denmark and are almost three times as big as the Pakistani community. Furthermore, a nationally representative study indicated that 56.4% of marriages in Pakistan were between first or second cousins, with little or no evidence of any change in prevalence during the preceding 40 years [18]. Studies conducted in Turkey indicated that about 20.1% of marriages were between first or second cousins [19], [20]. Direct comparison of the studies is difficult because of the different reporting methods used. However, the data suggest that frequency of consanguineous unions is generally higher among Pakistanis.

Newborns of Afghan origin had the highest prevalence of IEM (Table 3). This is most likely because consanguineous unions are common among Afghans, and that immigration from Afghanistan has increased significantly since 2001. A study conducted in 2011/2012 indicated that over 50% of marriages in Afghanistan were between consanguineous couples [21].

We acknowledge that a combination of biraderi endogamy, especially in relation to the Pakistani community, arrangement within ethno linguistic groups (Hazara, Pashtun etc.) and consanguinity are likely responsible for the high disease frequencies. However, we do not have any nation-wide data available on biraderi membership among the different ethnic groups to comment on it in the context of our study. Further, the relatively high number of diagnosed cases (41) referred from Greenland and The Faroe Islands is most likely explained by a founder effect [22]. The latter is a geographically isolated group of islands that originates largely from colonization by a small number of Norwegians about 1000 years ago. In a previous study by the authors (A.L., F.S.), it was observed that carnitine transporter deficiency (CTD) and holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency (HLCSD) were relatively frequent among patients referred from the The Faroe Islands to our department for diagnosis and treatment [23]. CTD and HLCSD have an estimated carrier frequency of about 1:20 for both disorders [23]. The birth rates of HLCSD and CTD among Faroese are about 1:1700 (DK 1:100,000) and 1:300 (DK 1:100,000), respectively. This provides an example of how most likely a founder effect and genetic drift have resulted in a unique national genetic disease profile.

Although there was a conspicuously high association between consanguinity and IEM, analysis of some non-genetic variables (age, parity, taxable income, household size), would have been instructive. Danish [24], [25] and many other international studies [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] have demonstrated that the high rate of infant death with inherited congenital disorders as a primary cause among some ethnic groups cannot be explained by the aforementioned variables. Furthermore, some of the studies that controlled for these risk factors still found consanguinity to be a major risk factor for congenital anomalies [15], [16]. Moreover, by investigating IEM with a recessive mode of inheritance, it is highly unlikely that the association reported would be strongly affected. This leads to the question of perhaps consanguinity being a major risk factor for the higher death rates from congenital abnormalities among some ethnic minorities. With ongoing demographic changes in Western countries, differences in health among offspring of some ethnic minorities have been observed in a number of studies where an increased risk of death in infancy was seen for offspring of immigrants [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. A Danish population-wide study showed an increased stillbirth and infant mortality rate among children of mothers of ethnic Turkish and Pakistani origin compared with ethnic Danish children [24]. A majority of the deaths were due to congenital anomalies, which is consistent with other international studies that found that inherited congenital conditions were one of the main causes of the excess risk of mortality. A Dutch study on early child mortality (0–2 years) found that deaths from hereditary diseases in the first 2 years of life were four to five times higher among Turkish immigrants [32]. Another study found that the leading cause of infant death among infants of mothers born in Pakistan and Bangladesh was congenital anomalies [33].

The study is the largest report of data for IEM in the offspring of consanguineous unions in Denmark. Our findings confirm that the offspring of consanguineous unions have an increased risk for IEM. Couples contemplating such unions should be advised of these risks; however, advice should be given with sociological awareness. Ethnic groups can have different perceptions of genetic disease and risk factors. This can have an impact on their preferences toward genetic counseling and treatment [34]. Linguistic barriers may also limit comprehension of genetic issues. A study found increased attendance of Pakistanis at a medical genetic clinic if a Pakistani doctor would also be present perhaps due to a better understanding of language and culture [35].

Demographic changes have significantly impacted on the patient profile of clinical genetic services in many countries [3], [4]. As a result, knowledge about the health outcomes of consanguinity is pertinent for health care professionals providing clinical genetic services and to primary care takers to assist consanguineous couples to make informed decisions about family planning. Perhaps even education programmes at secondary school level, and leaflets at relevant languages on recessive diseases and consanguinity might prove beneficial. The results of this study will hopefully increase knowledge and inform health personnel, who work with communities at increased risk.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Hutchesson A.C., Bundey S., Preece M.A., Hall S.K., Green A. A comparison of disease and gene frequencies of inborn errors of metabolism among different ethnic groups in the West Midlands, UK. J. Med. Genet. 1998;35(5):366–370. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.5.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bittles A., Black M.L. Global Patterns & Tables of Consanguinity. 2015. http://consang.net/index.php/Global_prevalence

- 3.Bennett R.L., Motulsky A.G., Bittles A. Genetic counseling and screening of consanguineous couples and their offspring: recommendations of the National Society of genetic counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 2002;11(2):97–119. doi: 10.1023/A:1014593404915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Port K.E., Mountain H., Nelson J., Bittles A. Changing profile of couples seeking genetic counseling for consanguinity in Australia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2005;132A(2):159–163. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund A.M., Hougaard D.M., Simonsen H. Biochemical screening of 504,049 newborns in Denmark, the Faroe Islands and Greenland—experience and development of a routine program for expanded newborn screening. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;107(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamamy H., Antonarakis S.E., Cavalli-Sforza L.L. Consanguineous marriages, pearls and perils: Geneva international consanguinity workshop report. Genet. Med. 2011;13(9):841–847. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318217477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen C.B. The Danish civil registration system. Scand. J. Public Health. 2011;39(7):22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denmark Statistics. Documentation of Statistics for Immigrants and Descendants. 2016. http://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/dokumentation/documentationofstatistics/immigrants-and-descendants/statistical-presentation

- 9.Denmark Statistics. Migrants and Their Descendants. 2017. http://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/nyt/GetPdf.aspx?cid=24085

- 10.Wilcken B., Wiley V., Hammond J., Carpenter K. Screening newborns for inborn errors of metabolism by tandem mass spectrometry. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(23):2304–2312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andresen B.S., Lund A.M., Hougaard D.M. MCAD deficiency in Denmark. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106(2):175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittles A. Consanguinity and its relevance to clinical genetics. Clin. Genet. 2001;60(2):89–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albar M.A. Ethical considerations in the prevention and management of genetic disorders with special emphasis on religious considerations. Saudi Med. J. 2002;23(6):627–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bittles A., Black M.L. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler Colloquium: consanguinity, human evolution, and complex diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(1):1779–1786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906079106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoltenberg C., Magnus P., Lie R.T., Daltveit A.K., Irgens L.M. Birth defects and parental consanguinity in Norway. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997;145(5):439–448. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheridan E., Wright J., Small N. Risk factors for congenital anomaly in a multiethnic birth cohort: an analysis of the born in Bradford study. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1350–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundey S., Alam H. A five-year prospective study of the health of children in different ethnic groups, with particular reference to the effect of inbreeding. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;1(3):206–219. doi: 10.1159/000472414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute of Population Studies . NIPS and ICG International; Islamabad, Pakistan and Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2013. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13.http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1918 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simşek S., Türe M., Tugrul B., Mercan N., Türe H., Akdağ B. Consanguineous marriages in Denizli, Turkey. Ann. Hum. Biol. 1998;26(5):489–491. doi: 10.1080/030144699282598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koc I. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of consanguineous marriages in Turkey. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2008;40(1):137–148. doi: 10.1017/S002193200700226X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saadat M., Tajbakhsh K. Prevalence of consanguineous marriages in west and south of Afghanistan. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2013;45(6):799–805. doi: 10.1017/S0021932012000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santer R., Kinner M., Steuerwald U. Molecular genetic basis and prevalence of glycogen storage disease type IIIA in the Faroe Islands. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;9(5):388–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund A.M., Joensen F., Hougaard D.M. Carnitine transporter and holocarboxylase synthetase deficiencies in the Faroe Islands. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007;30(3):341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villadsen S.F., Mortensen L.H., Andersen A.M.N. Ethnic disparity in stillbirth and infant mortality in Denmark 1981–2003. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2009;63(2):106–112. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen G.S., Mortensen L.H., Andersen A.M.N. Ethnic variations in mortality in pre-school children in Denmark, 1973–2004. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011;26(7):527–536. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vangen S., Stoltenberg C., Skjaerven R., Magnus P., Harris J.R., Stray-Pedersen B. The heavier the better? Birthweight and perinatal mortality in different ethnic groups. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002;31(3):654–660. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troe E.J.W.M., Kunst A.E., Bos V., Deerenberg I.M., Joung I.M., Mackenbach J.P. The effect of age at immigration and generational status of the mother on infant mortality in ethnic minority populations in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2007;17(2):134–138. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Troe E.J.W.M., Bos V., Deerenberg I.M., Mackenbach J.P., Joung I.M. Ethnic differences in total and cause-specific infant mortality in The Netherlands. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2006;20(2):140–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hessol N.A., Fuentes-Afflick E. Ethnic differences in neonatal and postneonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):e44–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balchin I., Whittaker J.C., Roshni R.P., Lamont R.F., Steer P.J. Racial variation in the association between gestational age and perinatal mortality: prospective study. BMJ. 2007;334(7598):833. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39132.482025.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ananth C.V., Shiliang L., Kinzler L.W., Kramer M.S. Stillbirths in the United States, 1981-2000: an age, period, and cohort analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95(12):2213–2217. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulpen T.W., van Wieringen J.C., van Brummen P.J. Infant mortality, ethnicity, and genetically determined disorders in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2006;16(3):290–293. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakeo A.C. Investigating variations in infant mortality in England and Wales by mother's country of birth, 1983–2001. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2006;20(2):127–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw A. eLS. 2016. Genetic counseling for Muslim families of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin in Britain; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts A., Cullen R., Bundey S. The representation of ethnic minorities at genetic clinics in Birmingham. J. Med. Genet. 1996;33(1):56–58. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]