Abstract

Medical leeches (Hirudo medicinalis) in plastic and reconstructive surgery are often used for the treatment of vascular failure after microvascular surgery. Leeches are a reservoir for bacteria of the Aeromonas group that help digesting the blood meal. In some cases these bacteria are able to cause severe wound infections that can lead to loss of tissue transplants. We report about a patient with a common microvascular forearm flap after resection of an oral squamous cell carcinoma which got infected by Aeromonas spp. after treatment with medical leeches. Most of these species are resistant for common antibiotic treatment after surgery. This report shows the importance of an early concomitant antibiotic prophylaxis in the treatment of venous congestion with medical leeches.

Keywords: Aeromonas, Leech therapy, Microvascular transplant, Hirudo medicinalis, Woundinfection, Fluorchinolon

Introduction

The use of medical leeches (Hirudo medicinalis) is a common option for the treatment of vascular failure after microvascular plastic and reconstructive procedures [1]. Leeches are widely used, especially for venous insufficiency after microvascular tissue reconstruction or organ transplantation to maintain proper circulation [2–4]. The most common leech related side effects comprise prolonged bleeding induced by anticoagulant effects and infection. Wound infection following leech therapy is often caused by bacteria, especially of the genus Aeromonas [5, 6], which have experienced frequent reclassifications in the past [7]. Aeromonas spp. are Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic rods causing septicemia and skin and soft tissue infections whereas their role in gastroenteritis is still controversial [7].

Particularly, Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria is the most prevalent species because it is a symbiont of the digestive tract of H. medicinalis [8, 9]. If these bacteria are secreted A severe adverse event caused by Aeromonas infection after leech therapy may be the loss of the transplant. For the prevention of this negative outcome, infections have to be treated by debridement and systemic antibiotic therapy in time [2].

We are presenting a typical case of flap infection caused by A. veronii complex with new information about how to prevent and treat an event like this.

Case Report

A 51-year old patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the left oral cheek (Fig. 1) underwent an anterior resection of the floor of the mouth, resection of the buccal mucosa up to the left labial angle and a bilateral selective neck dissection in level I–III [10] due to suspect lymph nodes in the B-mode sonography (Fig. 2). The defect was reconstructed with a free radial forearm flap from the left arm (Fig. 3). The patient was administered an anti-infectious therapy with ampicillin-sulbactam for one week.

Fig. 1.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 2.

Reconstruction of the enoral defect with a microvascular forearm flap

Fig. 3.

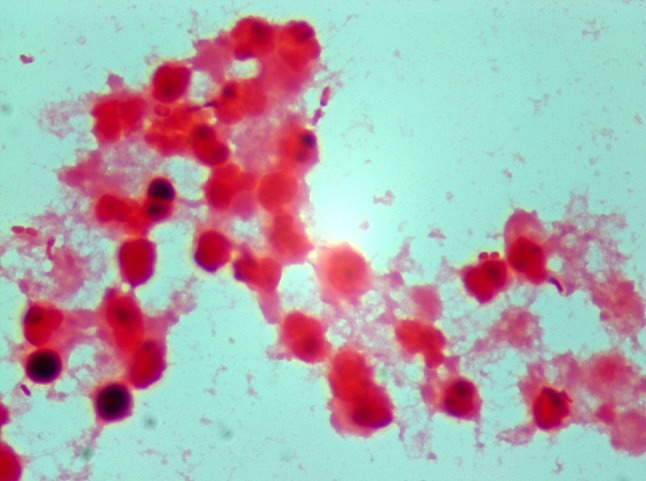

Direct Gram-stain (×1000) from the pus with microscopic detection of Gram-negative rods (Rightwards arrow)

On the first day after surgery, leech therapy was initiated because the forearm flap showed livid discoloration indicating a venous failure. Medical leeches were stored in distilled salt water, in a 200 ml container with a maximum amount of 5 animals per container. They were located in a dark and quiet area with a room temperature between 4 and 25 °C.

After 3 days of treatment with leeches twice a day clinical signs of vascular congestion disappeared. In each therapy session two leeches were used and guided with dental forceps without tweezing the animal. It took up to 5 min before the leeches were biting. The patient showed no infectious complications for nine days until a wound dehiscence under the left mandible developed. This was accompanied by raising inflammation parameters such as a C-reactive-protein level of 149 mg/dl (norm: <5 mg/L) and leucocyte counts of up to 11.6 cells/nl (norm; 3.5–10/nl). The antibiotic therapy was switched to piperacillin-tazobactam and pus was collected for microbiological analysis which revealed the direct microscopic detection of Gram-negative rods (Fig. 3) and a pure culture of bacteria of the A. veronii complex (Fig. 4). Based on the results of the susceptibility testing and considering tissue penetration, the therapy was changed to ciprofloxacin. Finally, complete wound healing was achieved.

Fig. 4.

Columbia blood agar plate with growth of A. veronii complex

Discussion

Leeches live of hemoglobin and its degradation products. They inject hirudin with their saliva as anticoagulant when sucking blood from their hosts [11]. Therefore, medicinal leeches are commonly used in plastic and reconstructive surgery to reduce the venous congestion of skin flaps. Further, each leech is able to extract up to 10 ml of blood from a flap with additional 50 ml that can be lost from the bite site after removal of the leech [12] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of isolates found in postoperative samples with respectively susceptibility as tested by NCCLS

| Isolates | No. of isolates | Sensibility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FQ | CF | SXT | ||

| A. hydrophilia | 2 | S | S | S |

| 1 | S | S | R | |

| A. sobria | 2 | S | S | R |

Table from Bauters et al. [17]

NCCLS National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, FQ fluoroquinolones, CF cefuroxime, SXT co-trimoxazole. Standard routine testing of quinolones involved ofloxacine (representative for levofloxacine, pefloxacin and ciprofloxacine also)

Leech therapy is known to cause infections in 2.4–20 % of the patients [13, 14]. Wound infection following leech therapy is often caused by bacteria of the genus Aeromonas [5, 6]. Aeromonas spp. are ubiquitous in nature and are mainly found in aquatic environments [7]. They also inhabit the digestive tract of H. medicinalis [8]. These bacteria are not only found in the digestive tract but also in the water the animals are stored inside [9]. In conclusion it must be assumed, that leeches excrete the bacteria via their bowel movements, their spit or both and that they can have them on their surface. The infections range from minor wound complications up to extensive tissue loss and sepsis, especially in patients with compromised arterial blood supply [12]. Beside a delayed onset after 10 days or more the highest risk of Aeromonas spp. infections occurs in the first days after leech therapy [4].

Aeromonas spp. are amongst others considered to be susceptible to extended-spectrum cephalosporins and fluorchinolones [7] which have been recommended as pre-emptive therapy using medicinal leeches [4]. However drug resistance has been reported, especially for ciprofloxacin [15]. In accordance with Bauter et al. [16] levofloxacin showed the best results in pre-emptive treatment and cost-effectiveness administered as 500 mg, twice daily. In contrast, less than 30 % of clinical isolates have been found to be susceptible to ampicillin-sulbactam [7]. In order to decrease tissue loss and severe infectious complications pre-emptive antibiotic therapy covering Aeromonas spp. should be considered in patients with medicinal leech therapy [4].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

For this type of study (retrospective case report) formal consent is not required. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

- 1.Martin G, Linnell JD, Yang SS, Lin J, Camarata PJ, Andrews BT. Ultrasound localization of a tunneled leech beneath a microvascular scalp reconstruction: a case report. Microsurgery. 2013;33:572. doi: 10.1002/micr.22163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dabb RW, Malone JM, Leverett LC. The use of medicinal leeches in the salvage of flaps with venous congestion. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29(3):250–256. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Chalain TM. Exploring the use of the medicinal leech: a clinical risk-benefit analysis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1996;12(3):165–172. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lineaweaver WC, Hill MK, Buncke GM, Follansbee S, Buncke HJ, Wong RK, et al. Aeromonas hydrophila infections following use of medicinal leeches in replantation and flap surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29(3):238–244. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitlock MR, O’Hare PM, Sanders R, Morrow NC. The medicinal leech and its use in plastic surgery: a possible cause for infection. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36(2):240–244. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson WA, Boothman P, Hare K. An unusual source of hospital wound infection. Br Med J (Clinical research ed). 1984;289(6460):1727–1728. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6460.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graf J. Symbiosis of Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria and Hirudo medicinalis, the medicinal leech: a novel model for digestive tract associations. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.1-7.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilmer A, Slater K, Yip J, Carr N, Grant J. The role of leech water sampling in choice of prophylactic antibiotics in medical leech therapy. Microsurgery. 2013;33(4):301–304. doi: 10.1002/micr.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cisco RM, Shen WT, Gosnell JE. Extent of surgery for papillary thyroid cancer: preoperative imaging and role of prophylactic and therapeutic neck dissection. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11864-011-0175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdualkader AM, Ghawi AM, Alaama M, Awang M, Merzouk A. Leech therapeutic applications. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2013;75(2):127–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orsini J, Sakoulas G. Surgical site infection complicating leech therapy. Internet J Plast Surg. 2006;3(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercer NS, Beere DM, Bornemisza AJ, Thomas P. Medical leeches as sources of wound infection. Br Med J (Clinical research ed). 1987;294(6577):937. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6577.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartor C, Limouzin-Perotti F, Legre R, Casanova D, Bongrand MC, Sambuc R, et al. Nosocomial infections with Aeromonas hydrophila from leeches. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(1):E1–E5. doi: 10.1086/340711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Alphen NA, Gonzalez A, McKenna MC, McKenna TK, Carlsen BT, Moran SL. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Aeromonas infection following leech therapy for digit replantation: report of 2 cases. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(3):499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauters T, Buyle F, Blot S, Robays H, Vogelaers D, Van Landuyt K, et al. Prophylactic use of levofloxacin during medicinal leech therapy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(5):995–999. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauters TG, Buyle FM, Verschraegen G, Vermis K, Vogelaers D, Claeys G, et al. Infection risk related to the use of medicinal leeches. PWS. 2007;29(3):122–125. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]