Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to determine the necessity and/or effectiveness of antibiotics in cases with maxillofacial trauma and emphasise the administration of antibiotics in maxillofacial fractures indicated for open reduction and rigid internal fixation (ORIF).

Materials and Methods

This study is a single blind, prospective, randomized clinical trial composed of subjects who presented with non-comminuted, linear fractures of the mandible and were treated by ORIF via an intraoral approach. One hundred and forty-four subjects (2011–2015) who belonged to the above entities were randomly categorized into 2 groups of 72 each, on lottery method. Patients in Group A were administered a 5 day course of antibiotic (1 day IV antibiotics followed by 4 days oral) while patients in Group B received a 1 day course of IV antibiotic (1 dose post op). Both the groups were followed up on the 1st day, 3rd day, 1st week, 1st month, 3rd month post operatively and were evaluated for pain, swelling, infection, fever, spontaneous wound dehiscence, purulent discharge and any other adverse effects.

Results

Post operative infection when measured clinically and radiographically was comparatively higher in Group B. Out of 72 patients in both the groups, 5 patients each in Group A and Group B reported with wound dehiscence, 9 patients in both groups developed pyrexia.

Conclusion

Though the post operative infection was slightly more in Group B compared to Group A, 1 day antibiotic regimen was found to be equally effective when compared to 5 day regimen and helps in reducing the after effects, superinfection and antibiotic resistance. It has better patient compliance and is cost effective.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, Infection, Superinfection

Introduction

Maxillofacial trauma has been studied extensively, yet, there is a decision of tree to be made for the use of prophylactic antibiotics during the management of such fractures. With a focus on perioperative antibiotic regimes, the head and neck region attracts attention because bacterial colonization is omnipresent and the number of severe postoperative infections is comparatively low. The latter is not surprising considering the superior immunologic structures and vascular supply of the tissues in maxillofacial region [1].The regular questioning of the benefit of general prophylactic antibiotics always remains an enigma to the surgeon. The anxiety with respect to postoperative complications, especially following management of maxillofacial trauma, led many surgeons to prescribe prolonged antibiotics thereby neglecting the adverse side effects. Furthermore, such protocols might support the development of antibiotic-resistant colonies and might involve unnecessary expenditure for the individual. In return, a higher level of safety for the well-being of the patient and the outcome of the operation is expected [2].The purpose of this prospective, clinical study is to investigate the necessity/effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics administered in the postoperative period after surgical management of isolated mandibular trauma.

Materials and Methods

The study sample consisted of 144 subjects who visited our department for the treatment of isolated fractures of the mandible from January 1, 2011 to June 1, 2015.They were randomly assigned to either Group A (5 day antibiotic regimen) or Group B (1 day antibiotic regimen).

Patients with the following inclusion criteria were included in the data set for analysis; open reduction and internal fixation for linear, isolated fractures on the mandible, with a follow-up of at least 6 weeks.

Patients with the following criteria were excluded (a) infected fracture at the time of treatment, (b) pathological fracture, (c) skull base fractures, (d) history of malignancy or (g) radiation to the head and neck area, (e) known hypersensitivity, (f) allergy to penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics, reduced body weight (<40 kg or BMI < 17), (h) insufficient patient compliance, insufficient follow-up. All the patients were standardized with same operating protocol under general anesthesia.

Antibiotic Protocol

All the subjects were administered either oral or intravenous antibiotics (Amoxicillin with Clavulanic acid and metronidazole) pre operatively. At the time of surgery the patients were randomized into 2 groups. Group A received 1 day course of IV antibiotics (Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid 1.2 gm and Metronidazole 500 mg) and 4 day course of oral antibiotics (Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid 625 mg and Metronidazole 400 mg).Group B received only 1 day course of IV antibiotics (Amoxicillin with clavulinic acid 1.2 gm and Metronidazole 500 mg) postoperatively.

Steroid Protocol

All the patients from both the groups received Dexamethasone 8 mg intravenously during the perioperative period on the day of surgery.

Outcome Measures

All the patients were evaluated post operatively according to the criteria for infections by CDC (Centre for Disease Control). The parameters evaluated were pain (VAS Scores), swelling, infection (clinical and radiographic), fever (>38 °C), spontaneous wound dehiscence, purulent discharge, duration of surgery (from the time of intubation to the time of extubation), associated soft tissue injury, duration between the injury and fixation, reduction approach, tooth in the line of fracture, adverse effects. All the subjects were followed up at 1st, 3rd day, 1st week, 1st month, 3rd month post operatively.

Swelling was evaluated as a mean of three line measurement with a flexible measuring tape [3] and measurements are made of the distances from as shown in Fig. 1.

Lateral canthus of the eye to the angle of the mandible.

Tragus to the outer corner of the mouth.

Tragus to the progonion.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of pre and post operative swelling using 3 line measurements

Infection was measured clinically and radiographically as suggested by Brett [4] shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Grading of infection clinically and radiographically

| Clinical | Radiographical |

|---|---|

| Grade I: Erythema around suture line limited to 1 cm | Grade I: Ossification of fracture site/no change from initial injury |

| Grade II: 1–5 cm of erythema | Grade II: Radiolucencies localized to hardware or necrotic tooth |

| Grade III: <5 cm of erythema and induration | Grade III: Generalized radiolucencies of fracture or hardware |

| Grade IV: Purulent drainage either spontaneously or by incision and drainage | |

| Grade V: Fistulae |

Statistical Analysis

The following information was obtained for each enrolled patient: age, gender, past medical history (HIV, Hepatitis, diabetes), habits (smoking, substance abuse), fracture locations, duration between injury and treatment, follow up period, time between treatment and diagnosis of infection (if occurred), duration of surgery. Descriptive analysis has been carried out with mean and standard deviation being compared. SPSS version 16 software has been used and comparison of categorical values was done using Independent sample T test. Significance for all tests was set at the p < 0.01 level.

Results

From January 2011 to June 2015, a total of 144 patients were enrolled in the study. All the subjects enrolled in the group shared similar demographic data. There were 126 men and 18 women with mean age of 29.82 years in Group A and 27.90 years in Group B. Duration between injury and definitive fixation was categorized as less than a week, greater than a week which was statistically not significant in both the groups. Duration of surgery was 146, 156 min in Group A, B respectively as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Age of patients, mean duration of surgery (in mins), time between injury and definitive fixation in both groups

| Group A | Group B | p < 0.01 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 day course | 1 day course | Statistical significance | |

| Age (in years) | 29.82 | 27.9 | p > 0.01 |

| Mean (SD) duration of surgery (in mins) | 146 | 156 | p > 0.01 |

| Mean (SD) time between injury and definitive fixation | p > 0.01 | ||

| >1 week | 75 % (54) | 77.5 % (56) | |

| <1 week | 25 %9 (18) | 22.5 % (16) |

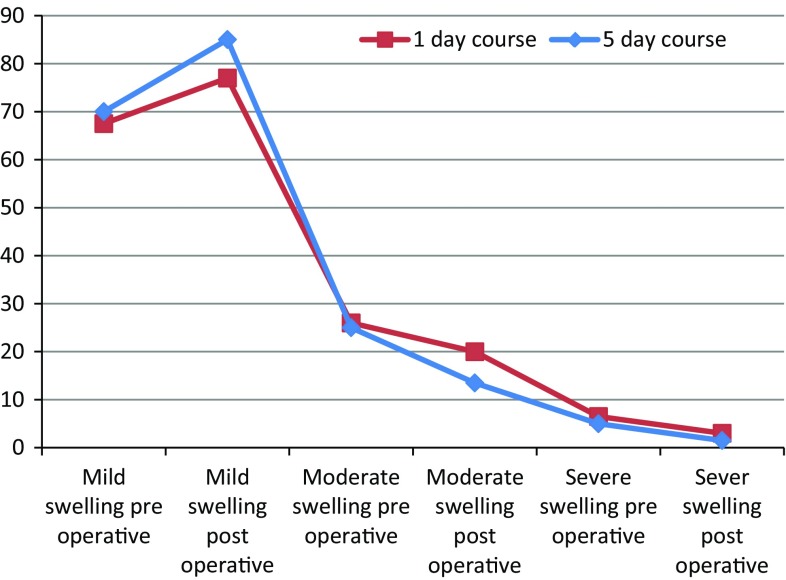

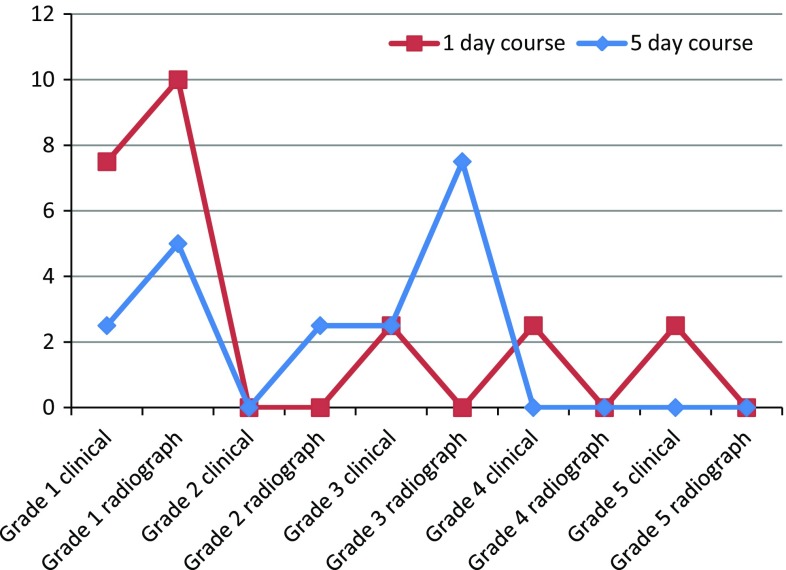

The difference in the amount of swelling pre and post operatively in Group A was 15 %, Group B was 7.5 % which was statistically significant (p < 0.01) as shown in Fig. 2. The mean VAS Score pre operatively in Group A and Group B were 1.40 and 1.35 respectively and post operatively 1.53, 1.49 in Group A, Group B respectively. Tooth in line of fracture was 17.5 % in Group A, 19 % in Group B. In both groups 12.5 % (9) developed fever (>38°). Wound dehiscence at 1st week follow up was 8 % (5) and 7.5 % (5) in Group A, B respectively as shown in Table 3. Hemodynamic variables in both the groups were consistent. Infection rates were measured pre and post operatively as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Swelling pre and post operatively in both groups

Table 3.

Pain scores, fever, tooth in line of fracture, wound dehiscence in both groups

| Group a | Group b | p < 0.01 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 day course | 1 day course | Statistical significance | |

| Pain (VAS scores) | p > 0.01 | ||

| Pre op | 1.4 | 1.35 | |

| Post op | 1.53 | 1.49 | |

| Fever | 12.5 % (9) | 12.5 % (9) | p > 0.01 |

| Tooth in line fracture | 17.5 % (13) | 19 % (14) | p > 0.01 |

| Wound dehiscence | 8 % (5) | 7.5 % (5) | p > 0.01 |

Fig. 3.

Infection rates clinically and radiographically in both groups

Discussion

Antibiotic prophylaxis is a part of standard protocol when managing maxillofacial injuries. However, various schools of thought exist pertaining to regimens of perioperative antibiotics. It is generally accepted that all maxillo-mandibular fractures involving the dentoalveolar segments are contaminated by the oral flora at the time of the injury. Prognosis of treatment of such fractures depends on various factors including age, habits of the patient, type and location of fracture, time of treatment, co-morbid conditions [5]. The male dominance of facial fractures was reported by Haug et al. [6] who retrospectively reviewed maxilla-mandibular fractures and justified that males are generally more prone to situations which are at higher risk of trauma [6] which was in agreement to our study. The regimen of prophylactic post operative antibiotics has been established by the work of Zallen and Curry [5]. Nonetheless, few researches suggested that antibiotic prophylaxis has no significant role in preventing surgical site infection (SSI) [5]. SSIs occur only in <1 % of patients undergoing treatment in head and neck regions, hence, in these cases, antibiotic prophylaxis is not thought to be beneficial [7, 8]. However, literature is sparse regarding the effect of antibiotics on maxillofacial fractures [9]. Aderhold et al. [10] determined the potential benefit of antibiotic administration in the first 48 h post operatively in 120 open mandibular fractures treated with miniplate osteosynthesis and concluded that it was effective in reducing the rate of infection, which was in agreement with the present study.

Duration of surgery has a bearing on the postoperative antibiotic requirement, as prolonged duration of tissue handling increases the local production of inflammatory substances and oedema, hence increasing the requirement for antibiotics [11]. Post operative swelling was lower compared to pre operative swelling in both the groups as IV Dexamethasone 8 mg was given post operatively. Gerlach, Pape et al. [12] studied 200 mandibular fractures with open reduction through an intraoral approach where a 1-day antibiotic regimen, 1-shot prophylaxis of antibiotics, 3-day course were used. It was concluded that a 1-day administration of antibiotics is sufficient to protect the patient from wound infection. Given the fact, that, fractures involving the tooth-bearing segments are contaminated at the time of injury as well as at the time of surgery, the use of perioperative antibiotics when dealing with these injuries is intended to prevent infection in a contaminated wound. Never the less it should not be confused with an infected wound that is a fracture site, presenting with erythema, purulence, fistulae, osteolysis, etc. which reveal clinical and radiographic evidence of active infection which obviously necessitates antibiotic administration. Abubaker and Rollert et al. [13] had conducted a pilot, double blind, placebo controlled study in 30 patients where 12 h postoperative antibiotics were compared with a 5 day course. The infection rate was 13 % in 12 h regimen and 14 % in 5 day regimen and concluded that postoperative oral antibiotics in simple fractures of the mandible had no benefit in reducing the incidence of infection [13] which was consistent to the results of the present study.

Miles et al. [4] conducted a prospective, randomized trial in 181 cases of open surgical treatment of mandibular fractures and concluded that there was no statistically significant benefit in administration of postoperative antibiotics in patients undergoing open reduction and internal fixation [4]. Despite the large sample size, this study had a few shortcomings namely, duration of antibiotic was not consistent and the follow up period was only for 6 weeks. Our study aims to address these loop holes as the follow up period was 3 months. Even if infection occurs, it would be evident around the hardware on the radiographs during the follow up. Nonetheless our study was in agreement with study conducted by Schaller et al. [14] that the use of postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis beyond the first 24 h did not seem to have a significant effect on postoperative infection rates.

The overall infection rates in our study accounted to 10 % which was higher than those of the earlier studies by Chole et al. [15]. The criteria adopted for diagnosis of infection was clinical and radiological as suggested by Miles et al. [4]. Wound dehiscence was comparatively lower but close to many previous studies that used antimicrobial prophylaxis [1, 16, 17] which could be attributed to inadequate tissue available during suturing which resulted in tension at the wound closure site and post-operative infection. Fever is a clinical sign of SSI and administration of prophylactic antibiotics would reduce fever [1, 18]. However in the present study no difference was found whole administering both the regimens. When other potential cofactors influencing infection like tooth in line of fracture was considered, the incidence of infection was high as suggested by Schaller et al. [14]. Though the tooth in line of fracture was 19 %, it did not influence the infection rates in the study. However, other confounding factors such as smoking, body mass index, multiple fractures, time from trauma to operation, duration of preoperative antibiotic treatment, duration of operation, or type of implant used, had no significant impact on the likelihood of postoperative infection and risk of infection of the surgical area reduces with an appropriate surgical technique, a good health of the patient [19, 20].

Conclusion

The fear of surgical site infection always remain a motivation for the use of antibiotics in non infected sites or in clean/contaminated surgical wounds. The results of our study suggest that there is no significant benefit in administration of 5 days regimen or 1 day regimen of antibiotics in patients undergoing open reduction and internal fixation for isolated fractures of mandible. However, 1 day antibiotic regimen is equally effective in minimising the risk of complications like superinfection and antibiotic resistance, while also being cost effective along with good patient compliance.

Acknowledgments

Would like to thank Dr. Pranavi, Dr. Sasank for their general support and assistance.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Patient Consent

Informed and written consent taken.

Ethical Standard

Institutional ethical board committee clearance obtained.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and Animals Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Kreutzer K, Storck K, Weitz J (2014) Current evidence regarding prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck and maxillofacial surgery. BioMed Res Int, Article ID 879437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Schwartz B, Bell DM, Hughes JM. Preventing the emergence of antimicrobial resistance: a call for action by clinicians, public health officials and patients. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;278:944–945. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550110082041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultze-Mosgau S, Schmelzeisen R, Frolich JC, Schmele H. Use of ibuprofen and methylprednisolone for the prevention of pain and swelling after removal of impacted third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53(1):2–7. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles BA, Potter JK, Ellis E., 3rd The efficacy of postoperative antibiotic regimens in the open treatment of mandibular fractures: a prospective randomized trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(4):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovato Christine, Wagner Jon D. Infection rates following perioperative prophylactic antibiotics versus postoperative extended regimen prophylactic antibiotics in surgical management of mandibular fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(4):827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haug RH, Prather J, Indrasano AT. An epidemiologic survey of facial fractures and concomitant injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(9):926–932. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90004-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JT, Wagner RL. Infection following uncontaminated head and neck surgery Archives of. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:368–369. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860040030010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simo R, French G. The use of prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck oncological surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:55–61. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193183.30687.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyzas PA. Use of antibiotics in the treatment of mandible fractures: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1129–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aderhold L, Jung H, Frenkel G. Untersuchungenüber den werteiner Antibiotika Prophylaxebei Kiefer-Gesichtsverletzungen. Eine prospective Studie. DtschZahnarztl Z. 1983;38:402. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna Nataraj. Efficacy of a single dose of a transdermal diclofenac patch as pre-emptive postoperative analgesia: a comparison with intramuscular diclofenac. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2012;18:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach KL, Pape HD. Studies on preventive antibiotics in the surgical treatment of mandibular fractures (in German) Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1988;12:497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abubaker A, Rollert M. Postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in mandibular fractures: a preliminary randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1415–1419. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.28272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaller B, Soong PL, Zix J, Iizuka T, Lieger O. The role of postoperative prophylactic antibiotics in the treatment of facial fractures: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot clinical study—part 2: mandibular fractures in 59 patients. Br J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chole RA, Yee J. Antibiotic prophylaxis for facial fractures. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860100033016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamphier J, Ziccardi V, Ruvo A, Janel M. Complications of mandibular fractures in an urban teaching center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:745–750. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potter J, Ellis E., III Treatment of mandibular angle fractures with a malleable noncompression miniplate. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:288–292. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90674-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhiwakar M, Clement WA, Supriya M, McKerrow W (2012) Antibiotics to reduce post-tonsillectomy morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12, Article ID CD005607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Coskun H, Erisen L, Basut O. Factors affecting wound infection rates in head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:328–333. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.105253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girod DA, McCulloch TM, Tsue TT, Weymuller EA., Jr Risk factors of complications in clean-contaminated head and neck surgical procedures. Head Neck. 1995;17:7–13. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]