Abstract

Background

Oroantral fistula (OAF) is considered a frequent complication in dental practice. Many surgical techniques/methods have been proposed to close it. The aim of this study was to evaluate the auto-transplantation of upper third molar for closing OAF.

Materials and Methods

Twenty patients participated in this study aged between 20 and 40 years old. The OAF was closed by auto-transplantation of upper third molar placed directly in the socket of the extracted tooth. Results were evaluated clinically and radiographically through the period of observation which lasted for 1 year.

Results

Final results showed that the success rate of closing OAF was 95% while the success rate of upper third molar auto-transplantation was 90%.

Conclusion

This technique is simple, applicable, provides immediate replacement of the missing tooth, and does not require complicated instruments or procedures.

Keywords: Oroantral fistula (OAF), Auto-transplantation, Extraction complications

Introduction

The maxillary sinus is a bony walls para-nasal cavity that forms a large space containing air in the maxilla and drains into the middle nasal meatus on the same side. It is also called Highmore’s antrum (named after Dr. Nathaniel Highmore in seventeenth century who described it as an air cavity in the maxilla and called it antrum) [1]. This antrum has pyramid shape with lateral recess bounded by the zygomatic bone, medial base bounded by the nasal cavity, and superiorly it is bounded by the orbital surface of the maxilla. Size of the sinus is ranging from 10 to 20 cm3 and can be found not more than 2 cm3 or maybe reaches a size of 30 cm3. Variations are commonly encountered in relationships between the maxillary teeth and floor of the sinus. First and second premolars and upper first molar (2.2% of cases) could be found with a clear and obvious relation with the sinus floor [2]. Root apices of these teeth appear to be into the lumen of the sinus and covered with thin bone separating them from sinus lumen. In rare cases, all teeth from cuspid to the third molar may be in contact with sinus floor. In these cases, direct communication between maxillary sinus and oral cavity could result from faulty extractions or using of curette instruments especially after extraction of teeth with periapical lesions or cysts [3]. OAF is mostly seen after the third decade of life [4–6]. Patients with oroantral communication complain air and fluids leakage to the oral and nasal cavity of the affected side. Valsava’s maneuver is a simple diagnostic test in which the patient is asked to blow the air from nose while the mouth and nose are closed [7, 8]. The OAF should be closed as soon as possible. This communication, if left open, will increasingly enhance the inflammatory process resulting from the transition of inflammation from the oral cavity to the sinus. When selecting the appropriate surgical technique for treating OAF, the following criteria should be taken into consideration: (1) Site and size of the fistula. (2) The relationship with the neighboring teeth. (3) Height of the alveolar ridge. (4) Presence and duration of sinus inflammation. (5) General health of the patient [9]. The present study aims to evaluate a new simple technique for closing OAF and replacing the missing tooth.

Materials and Methods

Twenty subjects were recruited from the outpatient who referred to the oral and maxillofacial department after they have been diagnosed with OAF as subsequent complication of upper first or second molar extraction. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Tishreen, and all participants signed an informed consent agreement. The selected patients fulfilled the following criteria: (1) No systemic or immune disease(s). (2) No hormonal disturbances. (3) For women, no pregnancy or breastfeeding. (4) No pathological signs/symptoms in the maxillary sinus. Periapical (Fig. 1) and panoramic radiographs were obtained for each patient. The OAF area was rinsed with a solution of normal saline and penicillin. The opening area was then closed temporarily by a piece of gauze. A local anesthesia was administered in the OAF area and the area of the upper third molar. After that, the upper third molar was carefully extracted and placed in a container glass which contains the previous solution. No any complications were encountered during removal of the third molars. Complete root canal therapy was performed (Fig. 2), and then, the third molar was placed into the new socket. This recipient socket was carefully prepared to receive the extracted third molar. In some cases, there were some modifications on the recipient socket. The interseptal bone was removed using special burs (round surgical bur no. 8), and the apex of the third molar was cut, using fissure bur, when needed (curved, malformed, and/or improperly sealed apices). The re-implanted third molar was raised 2 mm above the occlusal plane and maintained in its place by splinting wire (ligature wire 0.4 mm) alongside with suturing over the tooth (x-shaped suturing over the crown) (Fig. 3). Broad spectrum antibiotic (Augmentin) with anti-inflammatory drug (Profen) as well as mouth wash were prescribed for the patients. Follow-up system was arranged for 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Periapical and CT scan (Toshiba Asteion, 0.5–2 Gy, 3 s, 110 kV, 70 mA) radiographs (Fig. 4) were obtained for the latter three evaluation periods.

Fig. 1.

Periapical X-ray confirming the OAC

Fig. 2.

Endodontic treatment for the re-implanted third molar

Fig. 3.

Maintaining the third molar into the new socket

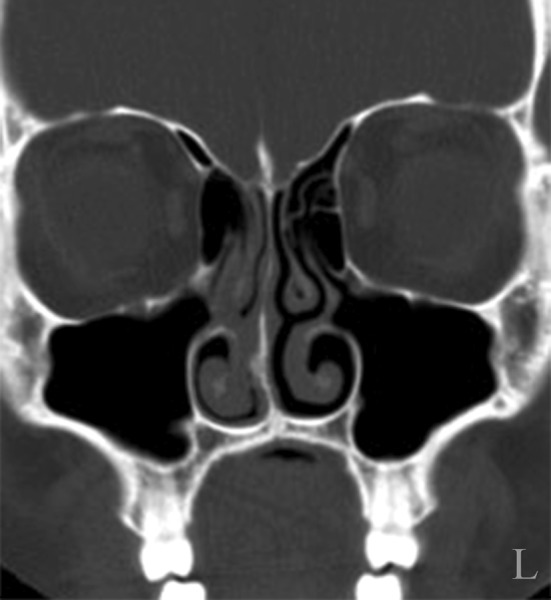

Fig. 4.

CT scan used for result evaluation showing the continuity of the sinus floor

Criteria for success were divided into three main groups:

- Radiographic criteria for success of auto-transplantation:

- Normal width of periodontal space around the re-implanted tooth (third molar).

- No signs of root absorption.

- Radio-opaque line at the septal bone (lamina dura).

- Clinical criteria for success of auto-transplantation:

- Normal movement of the re-implanted tooth (tested by Periotest®).

- Normal sound on percussion.

- No loss of attachment (no periodontal pocket).

- No signs of inflammation.

- Normal function of the tooth.

- Patient comfort.

- Radiographic criteria for success of OAF closure:

- Changes in the maxillary sinus observed by CT scan.

- Presence or absence of vapor in the sinus during the follow-up periods.

- Continuity of the sinus floor with bone formation.

Criteria for failure of auto-transplantation:

Root absorption.

Root fracture.

Loss of attachment.

Inflammatory process.

Results

Age of participants ranged from 20 to 40 years with a mean of (30.5 ± 4.7) years. Males were almost twice than female subjects (65 and 35%, respectively). Upper first molar showed to be the cause for most of cases (75% of cases) followed by upper second molar (25% of cases). Overall evaluation of the third molar re-implantation showed that the success rate was very high with 90% of cases while the failure was found with only two cases (10% of cases) (Table 1). In 95% of cases (19 cases), no hazy contents within the maxillary sinus was observed in the first time evaluation T1 (3 months after re-implantation). The number of hazy cases increased (two cases) in the second time evaluation T2 (6 months after re-implantation). However, decreasing in number of hazy cases (one case) was observed again after 1-year evaluation T3 (Table 2). Wilcoxon signed-ranks test with 95% confidence interval was utilized to identify the significance of differences between the periods of observations. No significant differences were observed between the recorded changes of the sinus contents in T1 and T2 observations of the third re-implantation (Table 3). Similarly, the differences between the recorded changes of sinus contents in T2 and T3 observations were also nonsignificant (Table 4). The recorded value of Periotest® for the re-implanted third molar after 3 months was (−1.25 ± 0.57), ranged from −2.30 to −0.30. Six months later, the value increased to record (1.22 ± 1.56) ranged from −3.10 to 3.00. A mean value of (2.45 ± 2.68) was recorded after 1 year of the third molar re-implantation ranged from −5.50 to 4.30 (Table 5). As shown in Table 6, there were significant differences between the readings of Periotest® during the observation periods (P = 0.001, 95% CI).

Table 1.

Distribution of the study sample by molar caused OAF and success rate of re-implantation

| (N) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Molar caused OAF | ||

| First molar | 15 | 75 |

| Second molar | 5 | 25 |

| Success rate | ||

| Failure | 2 | 10 |

| Success | 18 | 90 |

Table 2.

Number of hazy contents through the observational periods

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N) | (%) | (N) | (%) | (N) | (%) | |

| No hazy contents | 19 | 95 | 18 | 90 | 19 | 95 |

| Hazy contents | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 5 |

Table 3.

Differences between CT scan observations T1 and T2

| (N) | Mean rank | Sum of ranks | Z | P value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative ranks | 1 | 2 | 2 | −0.577 | 0.564 | NS |

| Positive ranks | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Ties | 17 |

Table 4.

Differences between CT scan observations T2 and T3

| (N) | Mean rank | Sum of ranks | Z | P value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative ranks | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 0.317 | NS |

| Positive ranks | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ties | 19 |

Table 5.

Means of the recorded values during observation periods

| (N) | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 20 | −2.3 | −0.3 | −1.25 | 0.58 | 0.13 |

| T2 | 20 | −3.1 | 3.00 | 1.22 | 1.56 | 0.34 |

| T3 | 20 | −5.5 | 4.8 | 2.46 | 2.69 | 0.60 |

Table 6.

Significance of the Periotest® recorded values for re-implanted third molar

| Mean | SD | SE | t | df | P value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 and 6 months | 2.46 | 1.45 | 0.32 | −7.57 | 19 | 0.001 | Sig. |

| 6 months and 1 year | 1.24 | 1.29 | 0.29 | −4.31 | 19 | 0.001 | Sig. |

| 3 months and 1 year | 3.7 | 2.54 | 0.57 | −6.50 | 19 | 0.001 | Sig. |

Discussion

The mean age of the study participants was (30.5 ± 4.7) years. This age is considered the most susceptible group to be affected with OAF. According to Abuabara et al. [10], OAF is mostly seen in the third decade followed by second decade of age. The authors related this to the fact that these age groups are often seeking for orthodontic treatment. As a part of treatment, the orthodontist may refer these patients for extraction of the third molar or any other tooth on the dental arch. Another reason might be related to the size of the sinus as the sinus reaches its largest size at this decade [11]. Other researchers recorded different age groups with OAF. Although Punwutikom et al. [6] did not find significant differences between the study age groups, they indicated that most OAF were seen in the age of 60 years or above. Yilmaz et al. [12] also indicated that OAF can be seen between 30 and 60 years. Loss of teeth and age progress may increase the occurrence of OAF.

In the current study, Males were more than female subjects. This result is in agreement with a previous study [12] in which they reported that males were twice more than females. This might be related to the fact that traumatic extraction is more common in males than in females [5, 13–16]. Out of the cases, 75% resulted from extraction of upper first molars, while 25% of the cases resulted from extraction of the upper second molar. These results accord with other reports [12–14, 16]. However, Von Bondsdorff et al. [17] reported that the roots of upper second molars are more close to the sinus floor followed by the first molar, second premolar, first premolar, and then the cuspid tooth. On the other hand, Abuabara et al. [10] indicated that the most related tooth with OAF is the third molar.

Even with the advantages of this technique which include immediate closing of OAF, replacement of the missing tooth without the need for fixed or removable denture, decreasing the healing time and avoid permanent changes in the depth of the buccal vestibule, there are still some points that should be taken into consideration such as success of re-implantation-especially in case of mature teeth, acute infection at the site of closing, chronic infection, and repeated failure of OAF treatment. This technique may be also not applicable in case of large fistula. Moreover, the technique requires the third molars with appropriate size and shape. Care should be taken when extracting the third molars as another OAF might occur. In addition, success of such procedure may be questionable in edentulous patients where the resorption of the alveolar ridge is more obvious. Some practitioners prefer buccal flap for closing small OAF and palatal flap for closing the large one [18, 19]. Others [10] suggested using buccal flaps, palatal flaps, or mucoperiosteal flaps for closing OAF surgically. However, no procedure has been proven to be superior over the others. Palatal flap has more blood supply, but it is more complicated procedure. In addition, the exposed bone structures of hard palate need more time for re-epithelization (2–3 months) resulting in patient’s discomfort and edema on the area. On the other hand, buccal flap is easier to perform but has less blood supply. It is also not indicated in case of large or recurrent OAF. Moreover, this type of flap may cause decreasing in the depth of the buccal vestibule. The decrease in the depth may be transient [13, 15] or permanent change in the vestibule [16, 20]. Subsequent complications appear when the removable prostheses become a part of the treatment plan [13, 15, 16, 20–22].

Comparisons between Periotest® values through the interval periods were significant (P < 0.05). These results indicate that with 95% CI there were statistically significant differences between the means of the recorded Periotest® values during the observation periods. Increase in these values could be recorded with increase in the observation intervals. In most cases, there was reconnection of the periodontal ligaments. This was confirmed by the Periotest® values and the normal physiologic movements of the re-implanted teeth. Two cases in the second time (T2) observation were seen with haziness appearance. This could be explained by the fact that the inflammation process continued a little bit longer after operation. This, in turn, explains that the number of haziness cases decreased in T3 observation period. However, the management of the failed cases was completed by removal of the transplanted teeth and administration of antibiotic alongside with anti-congestion (nasal drops) drugs. A number of limitations should be noted. First, this technique was applied only on OAF resulting from extraction of the molars. Second, this technique is only applied for small-size OAF. Finally, the cases were followed for only 1 year. Therefore, long-time observation period is recommended. In addition, histopathologic study is needed to point out the nature and stages of OAF closure.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that the proposed procedure can provide bone deposition for sinus borders and closing of the fistula. Moreover, it replaces the missing tooth with satisfactory function. Contralateral third molars can be used for closing OAF when the third molars of the ipsilateral are not suitable of closure. The following conditions should be taken into consideration:

Fistula with 5 mm or less.

The OAF resulted from extraction of the first or second molars.

Shape and size of the third molar are suitable.

No infection, pathological lesion, or bone destruction in the maxillary sinus.

References

- 1.Dunning WB, Davenport SE. A dictionary of dental science and art. Philadelphia: Blakiston Co.; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro JAC. The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: surgical anatomy. Berlin: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrowan DA, Baxter PW, James J. The maxillary sinus and its dental implications. 1. London: Wright; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guven O. A clinical study on oroantral fistulae. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:267–271. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(98)80024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin PT, Bukachevsky R. Blake M management of odontogenic sinusitis with persistent oro-antral fistula. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;70:488–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Punwutikorn J, Waikakul A, Pairuchvej V. Clinically significant oroantral communications—a study of incidence and site. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:19–21. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nezafati S, Vafaii A, Ghojazadeh M. Comparison of pedicled buccal fat pad flap with buccal flap for closure of oro-antral communication. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:624–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngeow WC. Buccal fat pad flap for the closure of oro-antral communication resulting from osteoradionecrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:547–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokler K, Vuksan V, Lauc T. Treatment of oroantral fistula. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2002;36:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuabara A, Cortez AL, Passeri LA, et al. Evaluation of different treatments for oroantral/oronasal communications: experience of 112 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:155–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sedwick HJ. Form, size and position of the maxillary sinus at various ages studied by means of roentgenograms of the skull. Am J Roentgenol. 1934;32:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitagawa Y, Sano K, Nakamura M, et al. Use of third molar transplantation for closure of the oroantral communication after tooth extraction: a report of 2 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:409–415. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Wowern N. Closure of oroantral fistula with buccal flap: Rehrmann versus Moczar. Int J Oral Surg. 1982;11:156–165. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(82)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killey HC, Kay LW. Observations based on the surgical closure of 362 oro-antral fistulas. Int Surg. 1972;57:545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bluesione CD. The management of oroantral fistulas. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1971;4:179–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amaratunga NA. Oro-antral fistulae—a study of clinical, radiological and treatment aspects. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Bonsdorff P (1925) Untersuchungen fiber Massverhaltnisse des Oberkiefers mit spezieller Beriicksichtigung der Lagebeziehungen zwischen den Zahnwurzein und der Kieferh6hle

- 18.Hori M, Tanaka H, Matsumoto M, et al. Application of the interseptal alveolotomy for closing the oroantral fistula. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1392–1396. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashely R. Method of closing antro-alveolar fistula. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1939;48:632–635. doi: 10.1177/000348943904800307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Junco R, Rappaport I, Allison GR. Persistent oral antral fistulas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:1315–1316. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860230109036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbert DC. Closure of a palatal fistula using a mucoperiosteal island flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1974;27:332–336. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(74)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamazaki Y, Yamaoka M, Hirayama M, et al. The submucosal island flap in the closure of oro-antral fistula. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:259–263. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]