Abstract

Introduction

There has been a changing trend of treating temporomandibular joint subluxation, which range from conservative non-surgical measures to various soft and hard tissue surgical procedures aimed at either augmenting or restricting the condylar path.

Aim

This study was aimed at comparing the efficacy of three major surgical treatment modalities: condylar obstruction creation, obstruction removal and anti-translatory procedures. Also, the location, anatomy and morphology of the TMJs pre- and post-surgery were evaluated and compared using radiographs, sagittal and 3-D Computed Tomographic scans.

Materials and Methods

A 6-year study was carried out on seventy-five patients of various age groups. Twenty-five were operated by the Dautrey’s procedure, 25 by articular eminectomy alone and the remaining 25 by eminectomy followed by meniscal plication and tethering. The distribution of patients in the three groups was random. Effectiveness of the surgical procedure and incidence of complications including recurrence were carefully compiled and compared between the three groups.

Results and Conclusion

Dautrey’s procedure yielded more gratifying and stable results, leading to a successful and permanent correction of chronic recurrent dislocation of the TMJs, with practically nil complications, thus demonstrating it to be an extremely safe, effective and versatile technique, making the joints function normally and securing sufficient volume of mouth opening. There was observed an average increase in articular tubercle height by 3.65 mm and a mean anterior shift of its lowest point by 4.5 mm following the Dautrey’s procedure, which were statistically significant findings. The upper age limit to carry out the Dautrey’s procedure can be safely taken up to 45 years.

Keywords: Subluxation, Hypermobility, Dautrey’s procedure, Eminectomy, Meniscal plication, Capsulorrhaphy, Arthroplasty

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) subluxation is an abnormal excessive excursion of the disk-condyle complex from its normal path, which translates anterior to its normal range in front and beyond the articular eminence during the opening of the mouth, with partial separation of the articular surfaces and depression in front of the tragus indicative of an empty glenoid fossa, a temporary locking or brief catching in that position, and then its return back to the glenoid fossa [1, 2]. This is usually accompanied by preauricular pain and a rough noisy clicking. Subluxations occurring repeatedly at long or short intervals are referred to as recurrent subluxations.

The stability of any joint depends on three main factors—the integrity of its capsule and ligaments, neuromuscular mechanism of the joint function and the osseous morphology of its bony components, such as the condyle, glenoid fossa, articular eminence, zygomatic arch and squamo-tympanic fissure. The condition of TMJ subluxation is usually attributed [2] to a combination of factors, including altered structural joint components like laxity/weakness of the TMJ ligaments and capsule; masticatory muscle dis-coordination, hyperactivity or spasm; variations in the osseous morphology, such as a hypoplastic zygomatic arch with a shallow and poorly grooved glenoid fossa, unusual articular eminence, which could be either atrophied, flat and poorly projected or elongated and steep with oblique inclines which evoke recurrent dislocations and make their reduction and repositioning particularly difficult, or a small, atrophic or malformed condylar head that slips readily out of the glenoid fossa. The condition may be brought on by a traumatic episode like forceful mouth opening during laryngoscopy/endoscopy [3], prolonged dental/ENT procedures, excessive mouth opening during yawning/laughing/vomiting or seizure/epileptic episodes, or abnormal chewing movements. Predisposing/aggravating factors include Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan’s syndrome [4], patients on neuroleptic analgesics [5], etc.

There has been a changing trend in the treatment of this condition. Conservative, non-surgical measures like introduction of sclerosing agents [6] or autologous blood into the joint [7], botox injection to cause a neuromuscular blockade [8], arthroscopic scarification of the capsule, etc., do not have much to offer in the long run, and it is the surgical soft and hard tissue procedures, aimed at either augmenting or restricting the condylar translatory path that provide stable and long-lasting results [9].

There have been scanty reports in the literature on studies comparing effectiveness of different surgical modalities in the correction of chronic recurrent TMJ subluxation and hypermobility [10]. This study is aimed at comparing the efficacy of the three major surgical treatment modalities, namely condylar obstruction creation, obstruction removal and anti-translatory procedures. Also, the locations anatomy and morphology of the TMJs post-surgery were evaluated and compared using radiographs, sagittal and 3-D Computed Tomographic scans.

The first modality (obstruction creation) by means of the Dautrey’s procedure aims at restricting the forward translatory condylar movement by creating a mechanical obstacle/obstruction in its path by augmenting the height of the articular eminence using the downfractured zygomatic arch [10]. The procedure was first introduced by Mayer in 1933, modified by LeClerc and Girard [11, 12], and was further refined and popularized by Dautrey [13]. The second modality, namely, obstruction clearance procedure [14], aims at eliminating the obstacle in the condylar path, allowing it to move forward and backward freely, thus making the joint a self reducing one. This was by reduction in the height of the articular eminence, i.e., eminectomy. Eminectomy was introduced by Myrhaug [15] and is still very popular in the management of chronic recurrent TMJ subluxation [16].

The third modality, namely, the anti-translatory procedure, involved meniscal plication and tethering to the retrodiscal tissue posteriorly and to the temporal fascia above [17–19].

Materials and Methods

A study was conducted over a period of 6 years from 2011 onwards, on seventy-five patients of ages ranging from 18 to 59 years (average age of 38 years), who presented with recurrent episodes of TMJ subluxation, with or without clicking, associated with preauricular pain, which often radiated to the temple, ear and neck, and which was non-responsive to conservative treatment measures. They were managed by three different surgical treatment modalities, and a comparative analysis was drawn as to the efficacy of these three management protocols.

Inclusion criteria (Table 1) included recurrent mandibular dislocations (at least three previous events), with or without TMJ clicking; pain in the region of the TMJs upon mouth opening, preauricular pain upon mastication and difficulty in chewing; an increased maximal interincisal mouth opening of 55 mm or more and clinically palpable and radiographically evident hypertranslation of the condyles.

Table 1.

Clinical features upon presentation

| S. No. | Clinical features | Percentage of patients |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Recurrent mandibular dislocation (bilateral/unilateral) | 70 (100%) |

| 2. | Clicking/popping sound from the TMJ, during opening and closing movements of the mandible | 58 (82%) |

| 3. | Pain in and around the TMJ region during mouth opening and mastication | 70 (100%) |

| 4. | Referred pain to the temple, forehead, neck etc. | 42 (52.5%) |

| 5. | Increased interincisal mouth opening (More than 55 mm) | 70 (100%) |

Exclusion criteria included skeletally immature patients below the age of 18 years, patients receiving major tranquilizers/neuroleptics for neuro-psychiatric diseases, seizure patients and those medically compromised patients who were systemically contraindicated for surgery.

All patients were conventionally and conservatively treated, for at least 3 months with dietary restrictions, muscle re-programming exercises, physical therapy with/without placement of class III elastics and mandibular anterior repositioning splints. When the aforementioned conservative methods proved to be ineffective and unsuccessful, the patients were then considered for surgery and a suitable surgical option was then selected randomly from the obstruction creation/clearance/anti-translatory procedures. The patients were placed randomly into three Groups A, B and C. No particular clinical, radiographic or MRI finding or criteria were employed in selection of the patients for any of the three surgical treatment options, and the choice of the surgical procedure was kept random.

Twenty-five patients were operated on by Dautrey’s procedure (Group A) (Fig. 1), twenty-five by articular eminectomy alone (Group B) (Fig. 7a–h) and the remaining twenty-five by combinations of articular eminectomy and arthroplasty in the form of meniscal plication to the retrodiscal tissue and to the temporal fascia above (Group C) (Fig. 7i–l). They were accordingly placed into Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Fig. 1.

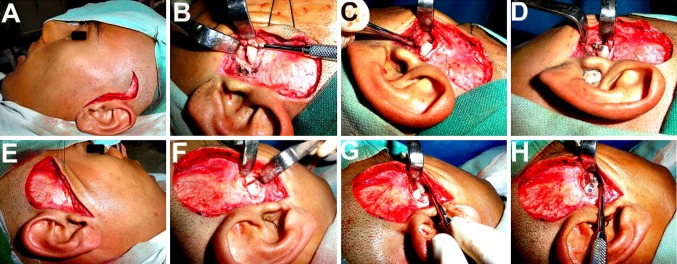

a, e Ivy and Blair’s modified preauricular incision, used to expose the TMJ and root of the zygomatic arch. b–d, f–h Osteotomy of the zygomatic arch followed by its downfracture, repositioning beneath the articular eminence and fixation using titanium minibone plate

Fig. 7.

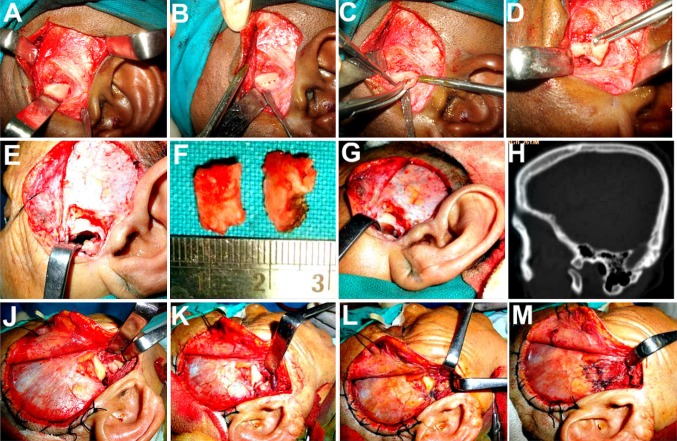

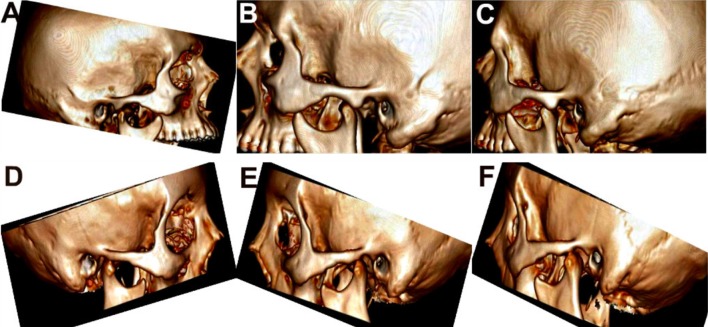

a–g Bilateral Articular eminectomy, a procedure entailing removal of the convex ridge of crest affording freedom of movement to the condyle and disk, making the joint a self reducing one. h Preoperative CT scan to gauge the degree of pneumatization of the eminence so as to prevent a possible perforation into the middle cranial fossa with a resultant CSF leak or temporal lobe exposure. i–l Eminectomy combined with meniscal plication and tethering. i, j Anteriorly displaced articular disk and condylar head, repositioned back in the glenoid fossa. k, l Lateral edge of the meniscus grasped and sutured to the lax bilaminar retrodiscal tissues behind, and to the temporal fascia and muscle above, thus preventing it from slipping forward and indirectly restraining the condyle as well

Ivy and Blair’s inverted hockey stick-shaped preauricular incision following the natural skin crease was employed, to expose the TMJ region (Fig. 1a). In patients treated by the Dautrey’s procedure, an oblique osteotomy cut was made in a downward and forward direction at the root of the zygomatic arch, just ahead of the articular eminence (Fig. 1b, f). A repetitive, firm and controlled pressure was then applied to the proximal end of the arch segment, which was carefully mobilized and maneuvered downwards, laterally and then inwards and locked under the eminence (Figs. 1, 2). A green stick fracture happens at the distal end of the segment, and the inherent rebound elasticity of the arch helps to maintain it in its new position allowing its cut end to spring upwards under the articular eminence, thus augmenting it. The aim is to maneuver the arch such that a true fracture at the distal end is avoided, as that would result in a loose piece of bone with no natural tension lock at the cut end. The same procedure was repeated on the other side, and fixation carried out using a straight or L-shaped titanium mini bone plates (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8).

Fig. 2.

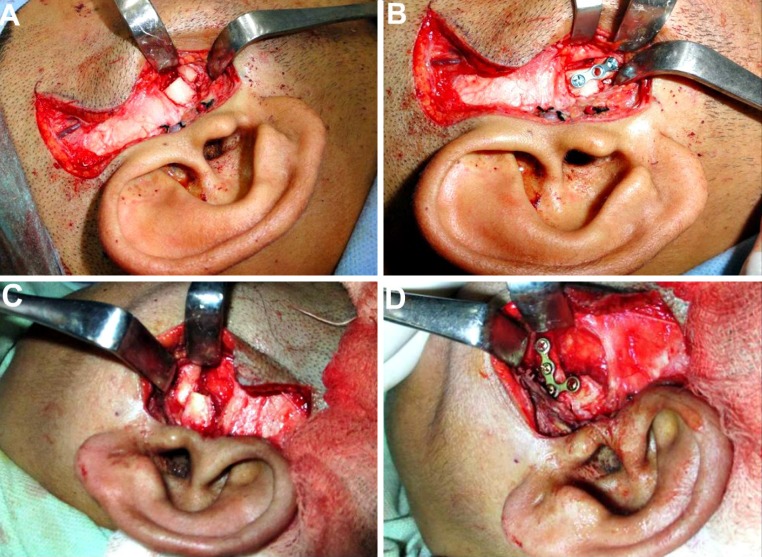

a, c Care is taken to push the downfractured arch, well medially to engage as much of the mediolateral width of the condyle as possible. b, d Straight or ‘L’-shaped titanium minibone plates and screws used for fixation of the proximal arch segment in the most optimal position

Fig. 3.

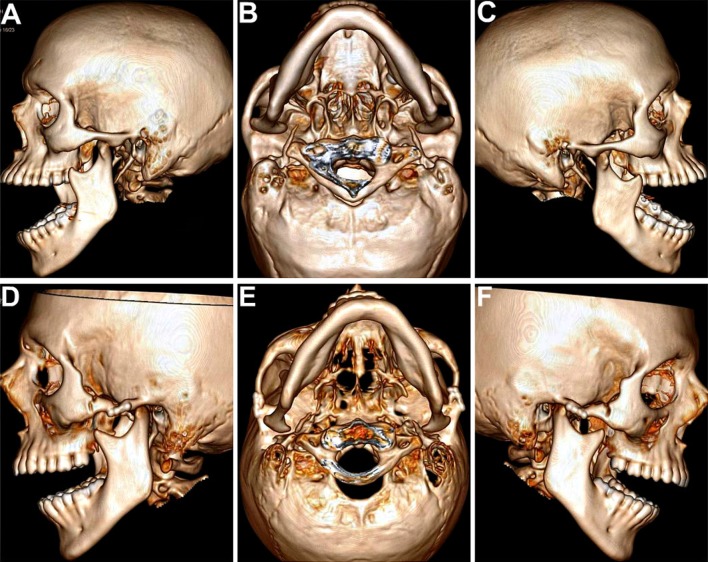

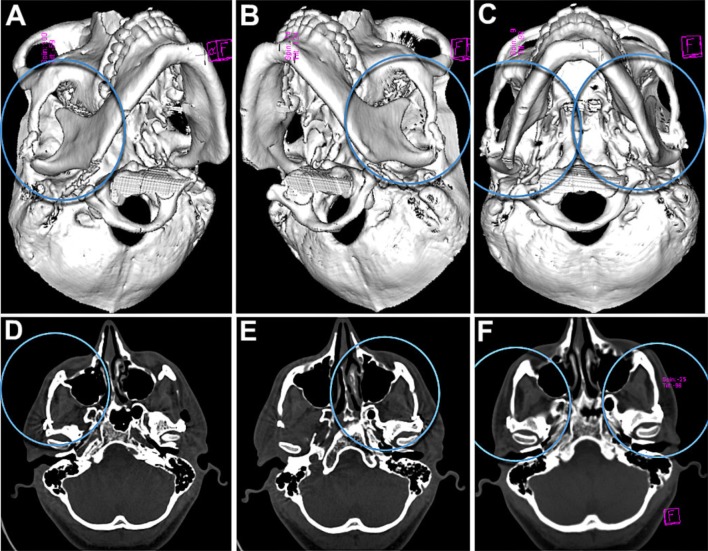

High-resolution spiral CT scans with 3-D reconstruction. a–c Preoperative scans showing excessive anterior translation and dislocation of the condyles out of the glenoid fossae and well past the anterior slope of the articular eminences, in the open mouth position, bilaterally. d–g Postoperative scans showing restriction in forward translation of the condyles, with the condylar heads successfully restrained within the glenoid fossae by the taller neo-eminences, following their augmentation by the downfractured zygomatic arches following the Dautrey’s procedure

Fig. 4.

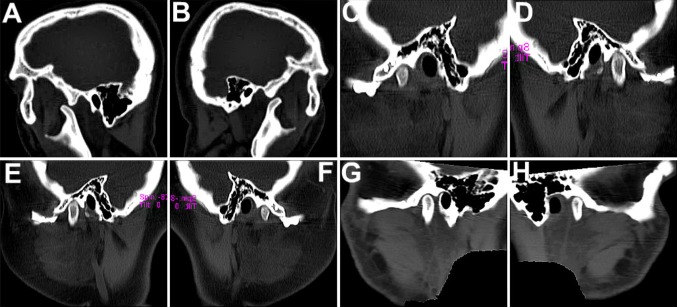

a, b Sagittal sections of CT scans showing forward dislocation of the condylar heads out of the glenoid fossae preoperatively, upon mouth opening. c–e, f–h Following the Dautrey’s procedure, the condylar heads are seen well restrained within the fossae by the augmented eminences. The downfractured arches with the fixation implants in situ are clearly seen, with the eminences being relocated more inferiorly and anteriorly. There was observed an average increase in articular tubercle height by 3.7 mm and a mean anterior shift of the lowest point of the articular tubercle by 4.5 mm following the Dautrey’s procedure

Fig. 5.

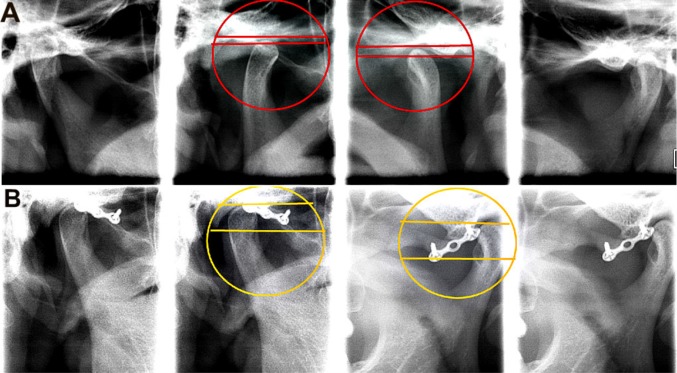

Simple transcranial radiographs can also be used to assess the increase in height of the neo-eminence achieved following the Dautrey’s procedure, by comparing the distance between 2 lines, the upper line drawn through the tip of the condylar head and the lower one through the tip of the articular eminence

Fig. 6.

1 year postoperative CT scans showing a good bony union at both, the distal fractured end of the arch as well as at the proximal augmented articular eminence region

Fig. 8.

Preoperative (a–c) and postoperative (d–f) 3-D CT scans showing a successful elimination of the convex crestal ridge from the condylar path, making the joint a self reducing one, following bilateral eminectomy

Twenty-five patients, placed in Group B, were treated by Articular eminectomy alone (Figs. 7a–h, 8), a procedure which entails removal of the convex ridge of crest, thus affording greater freedom of movement to the condyle and disk, making the joint a self reducing one. The inferior aspect of the eminence was removed using burs and vulcanite trimmers followed by closure of the capsule. Removal of the eminence in its entire medial extent was ensured in all the patients, to prevent any impingement of the condyle, but at the same time, care being taken to prevent breaching the medial soft tissue envelope, which could result in a troublesome bleed. Also, preoperative CT scans were carefully scrutinized in all patients to gauge the degree of pneumatization of the eminence so as to prevent a possible perforation into the middle cranial fossa that could result in a CSF leak or exposure of the temporal lobe. As some eminences have large marrow spaces, with a potential risk of infection, antibiotic therapy was employed preoperatively and postoperatively.

The remaining twenty-five patients, placed in Group 3, were treated with eminectomy combined with disk repositioning and meniscal plication and tethering to the lax retrodiscal tissues behind and to the temporal fascia above (Fig. 7i–l). After repositioning the forwardly displaced disk-condyle complex back within the glenoid fossa, the lateral edge/periphery of the cartilaginous disk was grasped and sutured to the lax bilaminar retrodiscal tissues and to the temporal fascia and muscle above and behind using 4-0 Vicryl horizontal mattress sutures (Fig. 7l), thus preventing it from slipping forward and stabilizing it against the forward pull of the lateral pterygoid muscle, fibers of which are inserted into the anterior band of the disk. This served to restrict the disk’s mobility and its tendency to slip forward on excessive mouth opening, which indirectly served as a restraint to the excessive forward translation of the condyle as well. The inferior aspect of the eminence was then removed using burs and vulcanite trimmers followed by closure of the capsule. Postoperative CT scans of Gp 2 and 3 patients (Fig. 8) showed a successful elimination of the convex crestal ridge from the condylar path, making the joint a smoothly self reducing one.

Results

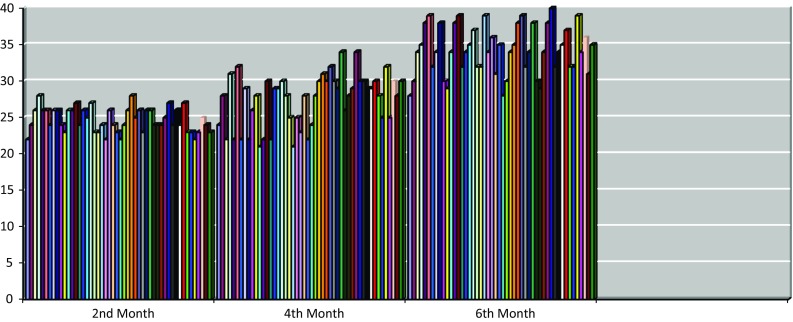

Post-surgical follow-up ranged from 8 to 36 months. Effectiveness of the surgical procedure, maximal postoperative interincisal opening (IIO) (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12; Table 2), together with the incidence of postoperative complications (Table 3; Fig. 13), were all carefully recorded, compiled and compared between the three groups. Also, the pre- and postoperative locations, anatomy and morphology of the TMJs with the relative positions of the zygomatic arch, articular eminence and condyle, were analyzed and compared using radiographs and CT scans (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 8).

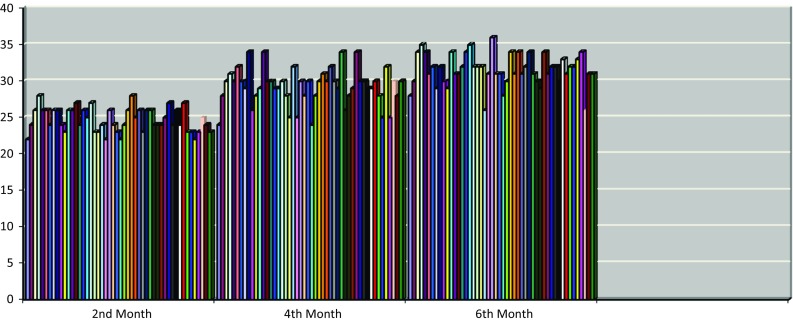

Fig. 9.

Postoperative mouth opening (Group 1)

Fig. 10.

Postoperative mouth opening (Group 2)

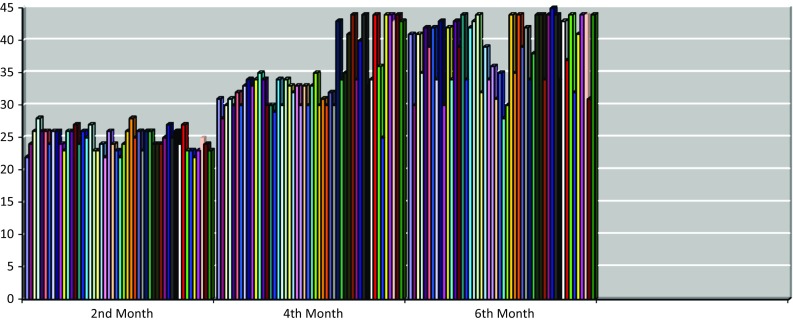

Fig. 11.

Postoperative mouth opening (Group 3)

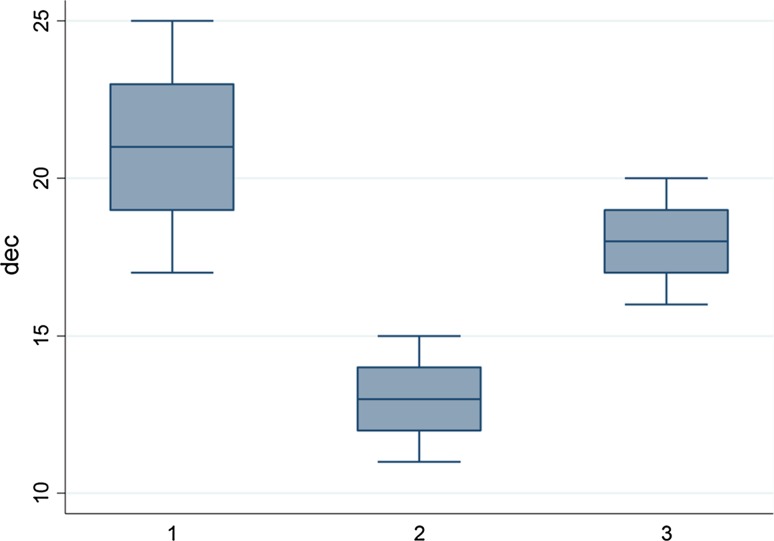

Fig. 12.

Box and Whisker plot diagram showing distribution of decrease in IIO (in millimeters) among all three groups, at the end of 6 months following surgery

Table 2.

Mean and SD distribution of decrease in IIO in each group at the end of 6 months following surgery

| Groups | No. of patients | Mean decrease in IIO (mm) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 25 | 21 | 2.531435 |

| II | 25 | 13 | 1.154701 |

| III | 25 | 18 | 1.490712 |

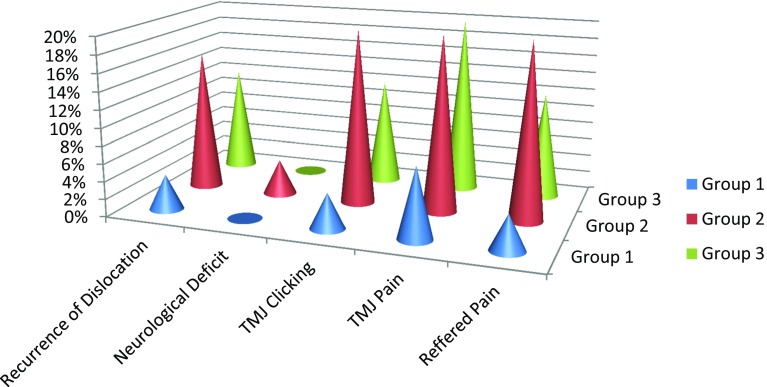

Table 3.

Comparison of incidence of complications post-surgery, between the three Groups

| S No. | Complication | Group 1 (n = 25) | Group 2 (n = 25) | Group 3 (n = 25) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Pts | %age | No. of Pts | %age | No. of Pts | %age | ||

| 1. | Recurrence of dislocation | 01 | 4 | 04 | 16 | 03 | 12 |

| 2. | Neurological deficit (frontal nerve weakness) | 00 | 0 | 01 | 4 | 00 | 0 |

| 3. | TMJ clicking | 01 | 4 | 05 | 20 | 03 | 12 |

| 4. | TMJ pain | 02 | 8 | 05 | 20 | 05 | 20 |

| 5. | Referred pain | 01 | 4 | 05 | 20 | 03 | 12 |

Fig. 13.

Comparison of incidence of complications post-surgery, seen in the three Groups (%age)

It was found that there was a total resolution of subluxation immediately following surgery and in the first postoperative year in all the three groups. Thereafter, there was recurrence seen in one patient each of Groups 2 and 3 in the second and third postoperative years, respectively, while there was nil recurrence among the Group 1 patients who were treated by the Dautrey’s procedure.

At the end of 6 months following surgery, the average minimal and maximal IIO (interincisal opening) was 26 and 36 mm in Group 1 patients (Fig. 9); 28 and 44 mm in Group 2 patients (Fig. 10) and 28 and 39 mm in Group 3 patients (Fig. 11). This indicated that the restriction in mouth opening was more following the Dautrey’s procedure as compared to the other surgical modalities, at the end of the initial 6 months (Fig. 12). Thereafter, a gradual increase in the IIO occurred, which settled within a range of 35–45 mm by 12 months in all the patients. Thus, all the three procedures resulted in statistically significant and stable decrease in mouth opening at the end of 12 months (as compared with the preoperative IIO of 55 mm or more).

Incidence of residual TMJ pain and clicking was more in the Gp 2 patients, treated by eminectomy alone, as compared to the other two groups. Although eminectomy prevented further dislocation of the joint, making it a self reducing one, it was found to encroach on the physiologic pattern of condylar movement, allowing it to hypertranslate, thus inviting meniscal injury and residual pain in many of the Group 2 patients. Better results were achieved in the third group as compared to Gp 2, when eminectomy was combined with arthroplasty in the form of meniscal plication and tethering to the lax retrodiscal tissues behind, and the temporal fascia above, which served to stabilize the joint better. There was nil incidence of residual TMJ pain and clicking among the Gp 1 patients.

Incidence of transient weakness of the Frontal division of temporal branch of the facial nerve was uniformly low in all the three groups. There was no incidence of salivary fistula or Frey’s syndrome seen in any of the patients. Other than mild postoperative pain and minimal edema at the operated site in the immediate postoperative period, no major complications occurred in any patient. Also, no patient developed any postoperative infection.

Upon comparing the pre- and postoperative 3-D CT scans in the open mouth position in patients treated by the Dautrey’s procedure, the condylar heads, which hyper translated past the articular eminences preoperatively, were found to be successfully restrained within the glenoid fossae by the taller neo-eminences, following the surgery (Fig. 3). Increase in height and change in position of neo-articular tubercle in cases treated by Dautrey’s procedure were assessed on transcranial radiographs of the TMJ (Fig. 5a, b),orthopantomograms as well as on 3-D reconstructed CT images (Fig. 6). An average increase was observed in articular tubercle height by 3.65 mm and a mean anterior shift of the lowest point of the articular tubercle by 4.5 mm following the Dautrey’s procedure, which was statistically significant findings. One year postoperative CT scans showed a good bony union at both, the distal fractured end of the arch as well as at the proximal augmented articular eminence region in these patients (Fig. 6). Fixation was carried out with miniplates and screws in all cases treated by the Dautrey’s procedure, which provided stable results. None of the patients required plate removal.

There was one complication seen in 2 patients treated by the Dautrey’s procedure. In the third postoperative year, there was noted a bit of resorption at the distal end of the arch segment; however, as it was fixed by a bone plate, it continued to serve as a free graft, augmenting the eminence and there was no recurrence of subluxation.

Discussion

Surgical treatment procedures for treating Chronic recurrent TMJ subluxation can be broadly classified into basic principles of anti-translatory procedures, like capsular plication, capsulorrhaphy, coronoid anchorage to the zygoma, scarification of the temporal tendon [20, 21], etc.; obstructing procedures, such as articular eminence augmentation [10–14]; obstruction clearance procedures such as condylectomy [15, 16], eminectomy [15–19] etc.; and reduction of muscular forces, as by lateral pterygoid/temporalis myotomy [20, 21, 22] or pterygoid disjunction [23].

Mayer [10] and later Le Clerc and Girard [11–13] reported on the procedure of osteotomizing the zygomatic arch and displacing a segment of it downward and forward just in front of the articular eminence to obstruct the condylar path. The procedure was refined by Gosserez and Dautrey [13, 14].

In the study carried out, the Dautrey’s procedure yielded more gratifying and stable results, as compared to articular eminectomy carried out either alone or in combination with meniscal plication and tethering, leading to a successful and permanent correction of chronic recurrent dislocation of the TMJs, with practically nil complications.

Going by literature reports, the Dautrey’s procedure is often not recommended over the age of 30 years [24–26] because the increasing hardness and brittleness of bone makes it difficult to achieve a green stick fracture at the distal end of the arch. Lawler [24] who reported on 10 cases suggested that patients aged over 32 years were probably not suitable for this technique because a fracture might occur more readily at the distal end of the zygomatic arch resulting in a loose piece of bone with no natural tensional lock between the cut end of the arch and the articular eminence. Such a loose piece of bone usually resorbs. It becomes necessary, therefore, to fix the arch at the distal end.

However, in this study, 7 patients out of the 50 in Gp I were between 35 and 45 years of age, and this complication could be averted and the Dautrey’s procedure was able to be successfully carried out without fracture of the arch, by slow and careful manipulation of the arch, yielding truly gratifying results. Thus, this study suggests that there may be no upper age limit for patients to undergo the Dautrey’s procedure. Also, this method does not employ interpositioning any graft/alloplastic material to increase the height of the articular eminence, unlike procedures such as the Norman’s and modified Norman’s technique which use calvarial, humeral, iliac or chin grafts and alloplastic materials [27–30].

There are 2 schools of thought as to the necessity of fixation of the downfractured arch. Fixation not only provides rigidity to the osteotomy site during healing ensuring a bony union between the cut end of the arch and the eminence, but also allows the downfractured arch to be retained in an optimal position, without slipping out, thus reducing the risk of recurrence, thus ensuring success and stability of this procedure [31]. Fixation using titanium minibone plates was employed in all the 50 patients of Gp 1, yielding stable results with no complication such as implant loosening, breakage or infection. Also, we recommended the downfractured arch be pushed as far medially as possible, under the articular eminence, so as to engage as much of the mediolateral width of the condyle as is feasible, in order to prevent recurrence of subluxation. This is particularly important when the condylar heads are small, atrophic or deformed.

A few advantages of eminectomy [17–19] are that it is less time taking, less invasive, does not encroach into the joint space, and does not involve any bony osteotomy of the arch, grafting or fixation. Removal of the eminence in its entire medial extent is critically important to prevent any impingement of the condyle [1]. But at the same time, care must be taken to prevent breaching the medial soft tissue envelope which could result in a troublesome bleed. Also, it is wise to take a preoperative CT scan to gauge the degree of pneumatization of the eminence so as to prevent a possible perforation into the middle cranial fossa resulting in a CSF leak or exposure of the temporal lobe. Since some eminences may have large marrow spaces, with a potential risk of infection [19], antibiotic therapy was employed preoperatively and postoperatively in all cases of Gp 1 and 2.

In Gp 2 patients, although eminectomy prevented further dislocation of the joint, making it a self reducing one, it was found to encroach on the physiologic pattern of condylar movement, allowing it to hypertranslate, thus inviting meniscal injury and residual pain in many of the patients. In this study and case series, it was found that relatively better results were achieved in the third group as compared to Gp 2, when eminectomy was combined with arthroplasty in the form of meniscal plication and tethering to the lax retrodiscal tissues behind and the temporal fascia above, which served to stabilize the joint better. Fibers of the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle insert into the anterior band of the articular disk. The forward pull by the muscle upon mouth opening, together with the laxity of the hitherto chronically stretched retrodiscal tissues (superior and inferior retrodiscal laminae), contributes toward making the disk vulnerable to anterior displacement, following reduction of the chronically dislocated joint. Stabilizing this articular disk by means of tethering it to the temporal fascia, over and above capsular plication, doubly ensures preventing this from happening post-surgery.

It was also evident from Table 3, with respect to incidence of complications between the three Groups, that the patients of group I had a far less incidence of Recurrence of dislocation (4%), TMJ Clicking (4%), TMJ pain (8%), Referred pain(4%) as compared to the two other groups. In view of above, the procedure followed in Group I had statistically far better results.

Conclusion

Dautrey’s procedure is an extremely effective and versatile, minimally invasive surgical technique, for the treatment of chronic recurrent TMJ Subluxation, designed to avoid interference with normal movements, and at the same time preventing abnormal forward excursive movements. It is a more efficacious procedure with fewer complications yielding more stable and long-lasting results as compared with obstruction clearance procedures such as eminectomy and anti-translatory procedures such as meniscal plication and tethering.

In this study, it was found that the downfractured zygomatic arch significantly increases the articular tubercle height and relocates the lowest point anteriorly and inferiorly, thereby preventing excessive anterior excursion of condyles beyond this point. The procedure thus makes the joints function normally and secures sufficient volume of mouth opening, without unduly restricting it. Fixation provides better rigidity of the osteotomized segment of the zygomatic arch and reduces the risk of recurrence. The advantages seen are that it does not violate the joint space and increases the height of the articular eminence without the need for a bone graft from another site or introduction of foreign material into the joint area. It affords long-lasting results, with practically nil complications or recurrence of subluxation. This study further demonstrated that the upper age limit to perform it successfully can be safely taken up to 45 years.

It was observed that the mean decrease in IIO among patients in Group I was highest, followed by patients in Group III and Group II. Further, one-way ANOVA was applied to see the difference among three groups with respect to decrease in IIO, which showed statistically significant difference between the three groups (P = 0.012) (Table 2).

Further, group analysis was carried out by using Bonferroni’s test for equal variances which showed that groups differ significantly from each other. The same has been shown in Box and Whisker plot diagram (Fig. 12).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author of this article has not received any research grant, remuneration, or speaker honorarium from any company or committee whatsoever, and neither owns any stock in any company. The author declares that she does not have any conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed on the patients (human participants) involved were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee, as well as with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments and comparable ethical standards.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the individual participants in this study.

References

- 1.Helman J, Laufer D, Minkov B, Gutman D. Eminectomy as surgical treatment for chronic mandibular dislocations. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;47:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babatunde BO. Evaluation of the mechanism and principles of management of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Systematic review of literature and a proposed new classification of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Head Face Med. 2011;7:10–14. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandari S, Swain M, Dewoolkar LV. Temporomandibular joint dislocation after laryngeal mask airway insertion. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2008;16:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauss O, Sadat-Khonsari R, Fenske C, Engelke W, Schwestka-Polly R. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction in Marfan syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Undt G, Weichselbraun A, Wagner A, Kermer C, Rasse M. Recurrent mandibular dislocation under neuroleptic drug therapy, treated by bilateral eminectomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24:184–186. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(96)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu WL, Ha Q, Hu QG. Treatment of habitual dislocation of the temporomandibular joint with subsynovial injection of sclerosant through arthroscope. Proc Chin Acad Med Sci Peking Union Med Coll. 1989;4:196–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daif ET. Autologous blood injection as a new treatment modality for chronic recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Perez D, Garcia Ruiz-Espiga P. Recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation treated with botulinum toxin: report of 3 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:244–246. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caminiti MF, Weinberg S. Review Chronic mandibular dislocation: the role of non-surgical and surgical treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998;64:484–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadre Kiran Shrikrishna, Kaul Deepak, Ramanojam Shandilya, Shah Shishir. Dautrey’s procedure in treatment of recurrent dislocation of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2021–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Undt G, Kermer C, Piehslinger E, Rasse M. Treatment of recurrent mandibular dislocation, Part I: Leclerc blocking procedure. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;26:92–97. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80634-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeClerc G, Girard G. Un nouveau proceed de butee dans le traitment chirurgical de la luvation recidivante de la manchoire inferieure. Mem Acad Chir. 1943;69:451–455. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosserez M, Dautrey J. Osteoplastic bearing for treatment of temporomandibular luxation. Transaction of second congress of the international association of oral surgeons Copenhagen, Munksgaard. Int J Oral Surg. 1967;4:261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dautrey J. Reflexions sur la chirugie de particulation temporomandibulaire. Stomologica Belg. 1975;72:577–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogrel MA. Articular Eminectomy for recurrent dislocation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:237–243. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(87)80024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato J, Suzuki T, Fujimura K. Clinical Evaluation of arthroscopic eminoplasty for habitual dislocation of the temporomandibular joint- comparative study with conventional open eminectomy. J Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:390–395. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg S. Eminectomy and meniscorrhaphy for internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. Rationale and operative technique. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oatis G, Baker D. The bilateral eminectomy as definitive treatment. J Oral Surg. 1984;3:294–298. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(84)80036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myrhaug H. A new method of operation for habitual dislocation of the mandible: review of former method of treatment. Acta Odontol Scand. 1951;9:247–261. doi: 10.3109/00016355109012789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskin DM. Myotomy for the management of recurrent and protracted mandibular dislocation. Trans Int Conf Oral Surg. 1973;4:264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould JF. Shortening of the temporalis tendon for hypermobility of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:781–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sindet-Pedersen S. Intraoral myotomy of the lateral pterygoid muscle for treatment of recurrent dislocation of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:445–448. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varghese Mani. Pterygoid plate disjunction: minimally invasive treatment for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;17:247–255. doi: 10.1016/S0915-6992(05)80020-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawler MG. Recurrent dislocation of the mandible : treatment of ten cases by the Dautrey procedure. Br J Oral Surg. 1982;20:14–21. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(82)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.To EWH. A complication of the Dautrey’s procedure. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:100–101. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90091-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi H, Yamazaki T, Okudera H. Correction of recurrent dislocation of the mandible in elderly patients by the Dautrey procedure. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38:54–57. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1999.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harsha BC, Turvey TA, Powers SK. Use of autogenous cranial bone graft in maxillofacial surgery: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(86)90008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson IT, Helden G, Marx R. Skull bone grafts in maxillofacial and craniofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(86)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medraa AM, Mahrous AM. Glenotemporal osteotomy and bone grafting in the management of chronic recurrent dislocation and hypermobility of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karabouta I. Increasing the articular eminence by the use of blocks of porous coralline hydroxyapatite for treatment of recurrent joint dislocation. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990;18:107–109. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revington PJD. The Dautrey procedure—a case for reassessment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]