Abstract

Congenital midline nasal masses are rare anomalies of which nasal glial heterotopia represents an even rarer subset. We report a case of a 25-day-old male child with nasal glial heterotopia along with cleft palate suggesting embryonic fusion anomaly which was treated with excision and primary closure for nasal mass followed by palatal repair at later date.

KEYWORDS: Cleft palate, midline nasal masses, nasal glial heterotopia, nasal glioma

INTRODUCTION

Congenital midline nasal masses include nasal dermoids, nasal gliomas, and encephaloceles. These are rare congenital anomalies, estimated to occur in 1:20,000–40,000 births. Although rare, these disorders are clinically important because of their potential for connection to the central nervous system. Nasal gliomas are one form of the congenital midline nasal masses that are rare, benign, congenital tumors, which arise from abnormal embryonic development. Here, we present a case report of a male child who presented with nasal glioma associated with cleft palate wherein glioma excision was performed at the 25th day of birth while palatal repair was done at 2 years of age.

CASE REPORT

A 25-day-old baby boy presented to our hospital with a midline swelling over his nose and upper lip. The swelling had been present since birth but did not cause any nasal obstruction or epistaxis. The baby also had an associated cleft palate [Figure 1]. He was born at full-term and had a normal vaginal delivery.

Figure 1.

Initial presentation

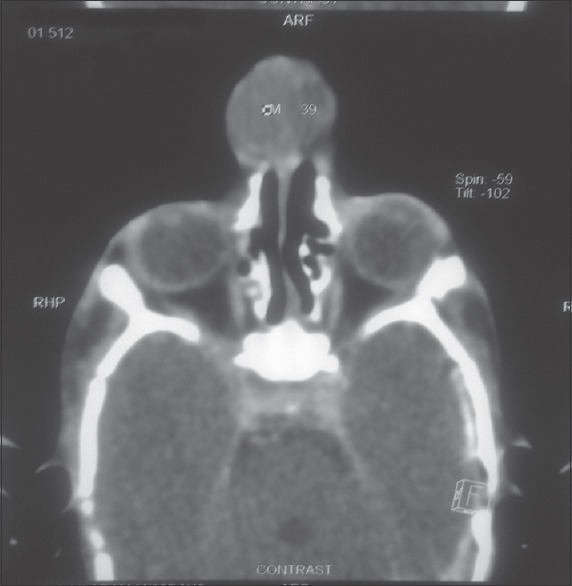

On physical examination, the baby had a dysmorphic facial expression with a 5 cm × 4 cm swelling extending from dorsum of nose to vermilion of upper lip. The swelling had a purplish hue with multiple telangiectatic vessels on its surface. It was neither tender nor pulsatile. There was no intranasal mass. The baby also had a type II cleft palate extending up to incisive foramen. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain showed a superficial midline nasal mass with no direct connection to the brain [Figure 2]. The mass was excised under general anesthesia using an elliptical incision and the defect closed primarily.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of nasal mass

Grossly, it appeared as a single skin covered polypoidal brownish mass while, on cut section, it was lobulated, well-circumscribed and multiple cysts were present. Microscopic sections demonstrated the presence of mature neuroglial tissue and leptomeningeal membrane with dilated and congested vascular channels.

The patient recovered well after surgery and his cosmetic outcome was satisfactory. His cleft palate was repaired at the age of 2 years. Mucoperiosteal flap coverage was done for the same with double-flap technique. Postoperative stay was uneventful. The patient may require further cosmetic correction at a later date in the form of rhinoplasty after he enters teenage.

DISCUSSION

Congenital midline nasal masses are rare anomalies, with a reported incidence of one in 20,000–40,000 live births.[1,2,3,4] While encephaloceles are the most common congenital midline nasal mass, dermoids, epidermoids, gliomas, teratomas, and hemangiomas are less commonly seen. Nasal gliomas are nonmalignant rests of heterotopic neural tissue and are one of several types of congenital midline nasal masses. Nasal gliomas are not true neoplasms as they originate from ectopic glial tissue left extracranially following abnormal closure of the nasal and frontal bone during embryonic development.[1,2,3,4] Therefore, some authors recommend using the term “glial heterotopia” or heterotopic glial tissue instead.[3]

The origin of heterotopic glial tissue is not understood. The following mechanisms, however, have been proposed:[5,6,7]

Encephalocele losing its cranial connection

Isolated totipotential cells giving rise to a glial tumor

Abnormal entrapment or migration of glial cells from the olfactory bulbs.

The encephalocele theory which states that heterotopic brain tissue in the head and neck arises from embryonic brain tissue trapped in inappropriate areas during development has now been largely accepted.

Nasal gliomas are typically located in the region of the glabella but can extend down to the nasal tip. They may manifest extranasally (60%), intranasally (30%), or both (10%), and only 15%–20% of them show intracranial communication.[3,5] In most reported cases, nasal glioma was not associated with other anomalies, but there are cases in which there are other malformations such as lip and palate cleft, choanal atresia, hydrocephalus, ureteral duplication, and extranumerary finger.[8] Uemura et al. published a review of 18 cases of which 7 were found together with a cleft palate.[4] The high incidence of cleft palate (43%) supports the encephalocele theory although it is still not clearly understood why in 57% of these cases the palate remains normal.[9]

Nasal gliomas are firm, noncompressible, do not increase in size with crying, and do not transilluminate. The overlying skin may have telangiectasias. Although high-resolution multiplanar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality for evaluating these lesions, it is limited in its ability to distinguish a true patent communication to the intracranial fossa from a fibrous stalk connection that is occasionally seen with nasal gliomas. CT scan, on the other hand, can be helpful for assessing bony defects although this modality may be of variable utility in young infants as the bony architecture is not fully formed.[10]

Surgical excision remains the mainstay of treatment and is required for a definitive histopathological diagnosis. A thorough preoperative imaging study is must before any attempt at removal of the glioma. Early surgical intervention is recommended to avoid severe complications such as meningitis or a brain abscess or cosmetic problems such as distortion of the septum and nasal bone.[11] Extranasal gliomas can be excised using an external approach by either a vertical elliptical midline incision or a horizontal incision over the dorsum of the nose.[12] Some authors recommend a conservative and cosmetic incision using an external rhinoplasty approach because nasal gliomas are benign and rarely recurrent.[3] For pure intranasal gliomas, a transnasal endoscopic approach is recommended for complete removal of the intranasal mass with no postoperative facial deformity.[3]

CONCLUSION

Heterotopic glial tissue associated with cleft palate is very rare. The high incidence of cleft palate in patients with heterotopic brain tissue in the nasopharynx supports the theory of trapped tissue in inappropriate areas during embryonic development. Associated cranial connection predisposes it to severe intracranial complications. Through clinical examination supplemented by radiological investigations such as MRI and CT scan help in arriving at an early diagnosis and timely surgical consultation. Conservative surgical excision remains the accepted modality of treatment due to rarely recurrent and nonmalignant potential of the mass.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Volck AC, Suárez GA, Tasman AJ. Management of congenital midline nasofrontal masses: Case report and review of literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2015;2015:159647. doi: 10.1155/2015/159647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Wyhe RD, Chamata ES, Hollier LH. Midline craniofacial masses in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2016;30:176–80. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahbar R, Resto VA, Robson CD, Perez-Atayde AR, Goumnerova LC, McGill TJ, et al. Nasal glioma and encephalocele: Diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2069–77. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verney Y, Zanolla G, Teixeira R, Oliveira LC. Midline nasal mass in infancy: A nasal glioma case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:324–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson K, Kapur S, Chandra RS. “Nasal gliomas” and related brain heterotopias: A pathologist's perspective. Pediatr Pathol. 1986;5:353–62. doi: 10.3109/15513818609068861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossen EH, Hudson WR. Oligodendroglioma arising in heterotopic brain tissue of the soft palate and nasopharynx. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:571–4. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gónzalez García M, Avila CG, López Arranz JS, García JG. Heterotopic brain tissue in the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:218–22. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkovich AJ, Vandermarck P, Edwards MS, Cogen PH. Congenital nasal masses: CT and MR imaging features in 16 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:105–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uemura T, Yoshikawa A, Onizuka T, Hayashi T. Heterotopic nasopharyngeal brain tissue associated with cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1999;36:248–51. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1999_036_0248_hnbtaw_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedlund G. Congenital frontonasal masses: Developmental anatomy, malformations, and MR imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:647–62. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-0100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oddone M, Granata C, Dalmonte P, Biscaldi E, Rossi U, Toma P. Nasal glioma in an infant. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:104–5. doi: 10.1007/s00247-001-0594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uzunlar AK, Osma U, Yilmaz F, Topcu I. Nasal glioma: Report of two cases. Turk J Med Sci. 2001;31:87–90. [Google Scholar]