Abstract

Background

In pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), combination therapy is an important treatment strategy. Although randomized controlled trial data are available to support the combination of two therapies, data regarding triple combination therapy are few.

Objective

The phase III GRIPHON trial enrolled 1156 patients with PAH, including 376 receiving background double combination therapy. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of selexipag as a third agent in these patients and further analyzed this subgroup according to symptom burden at baseline as indicated by World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (FC).

Methods

In this post hoc analysis, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using Cox proportional-hazard models to determine response to selexipag versus placebo on the composite primary endpoint of morbidity/mortality. Baseline characteristics and adverse events were summarized descriptively.

Results

Of 376 patients receiving background endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE-5i) therapy, 115 had WHO FC II symptoms and 255 had WHO FC III symptoms at baseline. The impact on the primary endpoint of adding selexipag versus placebo to double combination therapy was consistent with the effect in the overall population (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.44–0.90) as well as in patients with WHO FC II and III symptoms. Compared with the overall population, discontinuations due to an adverse event were higher when selexipag was added to background double combination therapy; no safety concerns were identified.

Conclusion

The addition of selexipag to background double combination therapy with an ERA and PDE-5i provides an incremental benefit similar to that seen in the overall population, including in patients with WHO FC II or III symptoms at baseline.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40256-017-0262-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| In patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) receiving background double combination therapy in the GRIPHON study, the addition of selexipag reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality, consistent with that observed for the overall population. |

| The beneficial effect of selexipag when added as a third agent to patients receiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was consistent in patients with World Health Organization functional class II or III symptoms at baseline. |

| These findings support escalation of treatment to triple oral combination therapy to improve outcomes for patients with PAH receiving double combination therapy. |

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare, progressive disease with a poor prognosis [1]. A number of therapeutic agents are available that target three of the pathways known to be involved in the pathobiology of PAH: the endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin (PGI2) pathways [2, 3]. A primary objective of PAH treatment is to delay progression of the disease [2, 3]. The use of PAH therapies in combination to target multiple pathways simultaneously is an important strategy for achieving this goal [2–5]. Double combination therapy is now established as the standard of care for patients with PAH [2, 3] and is becoming increasingly common in clinical practice [6–8]. The use of triple combination therapy to target three pathogenic pathways has also shown promise, but data supporting this approach are limited; one small, retrospective study has shown that triple combination therapy, including intravenous epoprostenol, may provide benefits for treatment-naive, incident patients with severe PAH [9].

The GRIPHON study was the largest event-driven outcome trial in patients with PAH [10]. This phase III randomized, placebo-controlled study enrolled 1156 patients with PAH and investigated the efficacy and safety of the oral, selective IP prostacyclin-receptor agonist selexipag [10]. Selexipag reduced the risk of experiencing a composite primary endpoint event of morbidity/mortality by 40% (hazard ratio [HR] 0.60; 99% confidence interval [CI] 0.46–0.78; p < 0.001) compared with placebo [10]. Importantly, at baseline, 32.5% of patients (n = 376) were receiving double combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor (PDE-5i) [10], a subgroup that was pre-specified for evaluation of the study’s primary endpoint.

The GRIPHON trial provides the opportunity to evaluate the addition of selexipag as a third oral agent in patients receiving double oral combination therapy at baseline. In these post hoc analyses, we investigate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of selexipag compared with placebo in the subgroup of patients receiving an ERA and PDE-5i at baseline. As this population consisted primarily of patients with World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (FC) II or III symptoms at baseline, we further assessed the effect of selexipag as part of a triple combination therapy regimen according to symptom burden as indicated by WHO FC.

Methods

Study Population

The GRIPHON trial has been described in detail previously [10]. In brief, GRIPHON was a global, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, event-driven phase III clinical trial (NCT01106014). The study population included patients aged 18–75 years with a confirmed diagnosis of PAH. Eligible patients had a 6-min walk distance (6MWD) of 50–450 m and a pulmonary vascular resistance of at least 5 Wood units (400 dyn s cm−5) at baseline. The study enrolled patients with idiopathic or heritable PAH or PAH associated with connective tissue disease (PAH-CTD), human immunodeficiency virus infection, or drug/toxin exposure, as well as those with repaired (for ≥ 1 year) congenital simple systemic-to-pulmonary shunts. Patients who were treatment naive or receiving an ERA, a PDE-5i, or both, at doses that were stable for at least 3 months prior to randomization were eligible [10]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Study Design

Following screening, patients were randomized (1:1) to receive oral selexipag or placebo twice daily (bid). During a 12-week titration period, selexipag was initiated at a dose of 200 µg bid and titrated weekly in increments of 200 µg bid to the highest tolerated dose. The maximum dose allowed was 1600 µg bid. Following this titration period, patients entered the maintenance period. The individualized maintenance dose (IMD) was defined as the dose the patient received for the longest duration in the study. IMDs were described according to three pre-specified dose categories: low (200 and 400 µg bid), medium (600, 800, and 1000 µg bid), or high (1200, 1400, and 1600 µg bid) [10].

The end of the double-blind treatment period was either when the patient experienced a primary endpoint event, when the patient prematurely discontinued study drug, or at the end of the study. The end of the study was declared when the pre-specified number of primary endpoint events was reached (331 events) [10]. Patients who discontinued double-blind treatment due to a non-fatal primary endpoint event were eligible to receive open-label selexipag or commercially available drugs [10]. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by local institutional review boards or independent ethics committees.

Outcome Measures

The primary composite endpoint was the time to the first morbidity or mortality event. These events included disease progression, worsening of PAH resulting in hospitalization, initiation of parenteral prostanoid therapy or long-term oxygen therapy, the need for lung transplantation or balloon atrial septostomy, or death from any cause. Disease progression was defined as a decrease from baseline of ≥ 15% in 6MWD (confirmed by a second test on a different day) as well as worsening in WHO FC for patients in WHO FC II or III at baseline or the need for additional PAH treatment for patients in WHO FC III or IV at baseline. The primary endpoint was determined from randomization to the end of the double-blind treatment period. All primary endpoint events were adjudicated by a blinded independent critical-event committee [10]. Secondary endpoints included death due to PAH or worsening of PAH leading to hospitalization up to the end of double-blind treatment, and death from any cause up to the end of study. Adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs) were recorded throughout the study and up to 7 and 30 days, respectively, after end of treatment [10].

Statistical Analyses

This post hoc exploratory analysis was conducted in patients receiving double combination therapy with an ERA and a PDE-5i at baseline. Kaplan–Meier estimates with 95% CIs were calculated for all time-to-event endpoints. Cox proportional-hazard models were used to estimate the HRs, with 95% CIs. Analyses of patients with WHO FC II and III at baseline were conducted with and without adjustment for baseline 6MWD, a parameter with known prognostic relevance in PAH [11].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 1156 patients enrolled in GRIPHON, 376 were treated with an ERA and a PDE-5i at baseline (double combination therapy group): 179 in the selexipag arm and 197 in the placebo arm [10]. Of these 376 patients, at baseline, 115 had WHO FC II symptoms (55 selexipag, 60 placebo), 255 had WHO FC III symptoms (122 selexipag, 133 placebo), and six had WHO FC IV symptoms (two selexipag, four placebo). In this analysis, we describe the double combination therapy group overall and according to WHO FC II and III symptoms at baseline. Because of the low number of patients with WHO FC IV symptoms at baseline, this group was not evaluated further.

The baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment arms (Table 1). The majority of patients had idiopathic PAH (59.2% for selexipag and 59.9% for placebo) and were female (79.9% for selexipag and 79.2% for placebo). The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age was 50.6 ± 15.00 years for selexipag and 50.7 ± 14.24 years for placebo. As would be expected, compared with the overall GRIPHON study population, patients in the double combination therapy group had a longer time from diagnosis, and a greater proportion were enrolled in Western Europe/Australia and North America [10]. Considering patients according to symptom burden at baseline, those with WHO FC III symptoms had a 6MWD approximately 50 m shorter than those with WHO FC II symptoms. They were also older, and a greater proportion had PAH-CTD.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics in patients receiving double combination therapya at baseline

| Characteristic | Overallb | WHO FC II symptoms at baseline | WHO FC III symptoms at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selexipag (N = 179) | Placebo (N = 197) | Selexipag (N = 55) | Placebo (N = 60) | Selexipag (N = 122) | Placebo (N = 133) | |

| Female sex | 143 (79.9) | 156 (79.2) | 46 (83.6) | 48 (80.0) | 96 (78.7) | 105 (78.9) |

| Age (years) | 50.6 ± 15.00 | 50.7 ± 14.24 | 47.6 ± 15.69 | 46.6 ± 13.75 | 51.8 ± 14.57 | 52.2 ± 14.19 |

| Geographical region | ||||||

| Asia | 12 (6.7) | 17 (8.6) | 6 (10.9) | 6 (10.0) | 6 (4.9) | 11 (8.3) |

| Eastern Europe | 8 (4.5) | 11 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 8 (6.6) | 9 (6.8) |

| Latin America | 10 (5.6) | 12 (6.1) | 5 (9.1) | 10 (16.7) | 4 (3.3) | 2 (1.5) |

| North America | 57 (31.8) | 50 (25.4) | 20 (36.4) | 16 (26.7) | 37 (30.3) | 33 (24.8) |

| Western Europe/Australia | 92 (51.4) | 107 (54.3) | 24 (43.6) | 26 (43.3) | 67 (54.9) | 78 (58.6) |

| Time since PAH diagnosisc (years) | 4.0 ± 4.39 | 3.6 ± 3.33 | 4.3 ± 4.31 | 3.6 ± 3.00 | 3.9 ± 4.47 | 3.6 ± 3.49 |

| PAH classification | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 106 (59.2) | 118 (59.9) | 32 (58.2) | 40 (66.7) | 72 (59.0) | 74 (55.6) |

| Heritable | 9 (5.0) | 9 (4.6) | 6 (10.9) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (2.5) | 7 (5.3) |

| Associated with CTD | 40 (22.3) | 56 (28.4) | 10 (18.2) | 11 (18.3) | 30 (24.6) | 45 (33.8) |

| Associated with corrected congenital shunts | 10 (5.6) | 10 (5.1) | 4 (7.3) | 3 (5.0) | 6 (4.9) | 7 (5.3) |

| Associated with HIV infection | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Associated with drug/toxin exposure | 12 (6.7) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.3) | 10 (8.2) | 0 (0) |

| 6-min walk distance (m) | 359.7 ± 80.97 | 358.7 ± 79.73 | 398.9 ± 55.45 | 392.9 ± 61.44 | 342.4 ± 84.94 | 348.8 ± 76.88 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

CTD connective tissue disease, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, WHO FC World Health Organization functional class

aReceiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor

bIncludes six patients with WHO FC IV symptoms at baseline

cThe diagnosis was confirmed by right heart catheterization

Selexipag Exposure and Dose

The median (interquartile range [IQR]) exposure to selexipag and placebo was 63.1 weeks (30.3–104.0) and 63.7 weeks (38.0–102.1), respectively. In the selexipag group, 20.1% of patients had their IMD in the low-dose group, 36.3% in the medium-dose group, and 41.3% in the high-dose group (Table S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). These proportions were consistent with those observed in the overall GRIPHON study population [10] and were comparable for patients with WHO FC II or III symptoms at baseline (Table S1 in the ESM).

Primary Endpoint

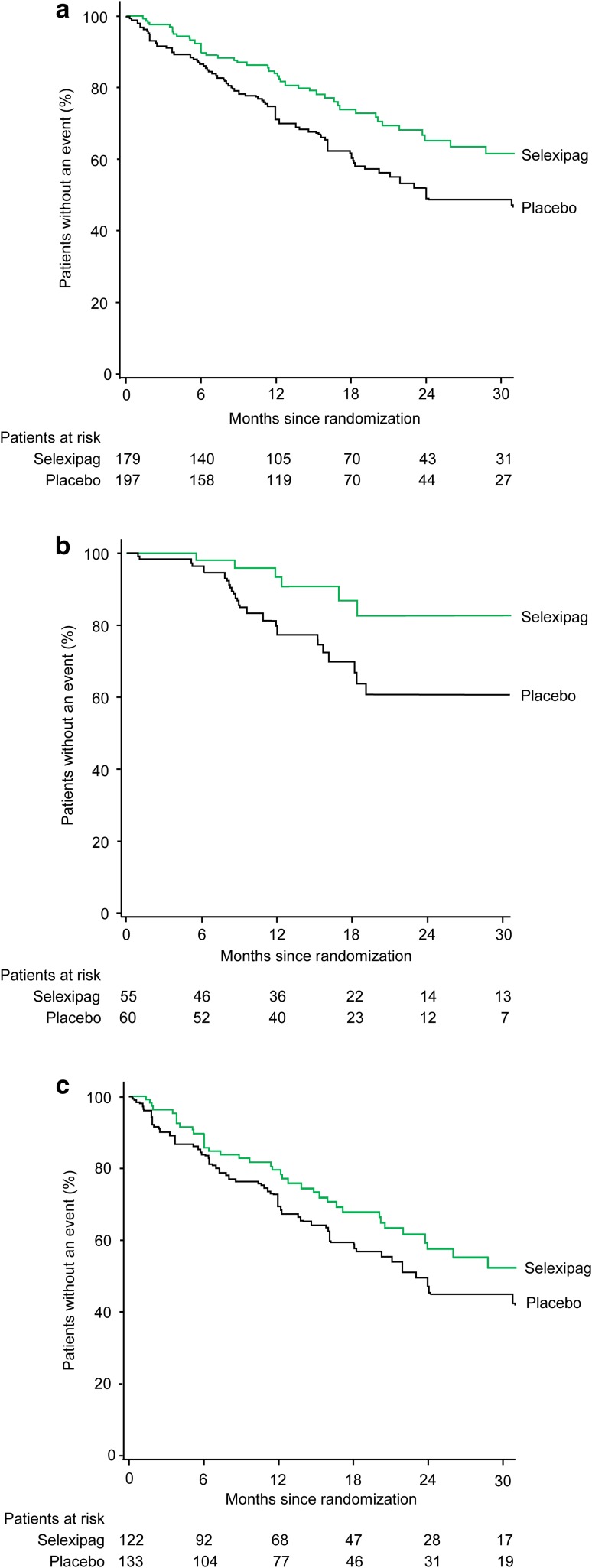

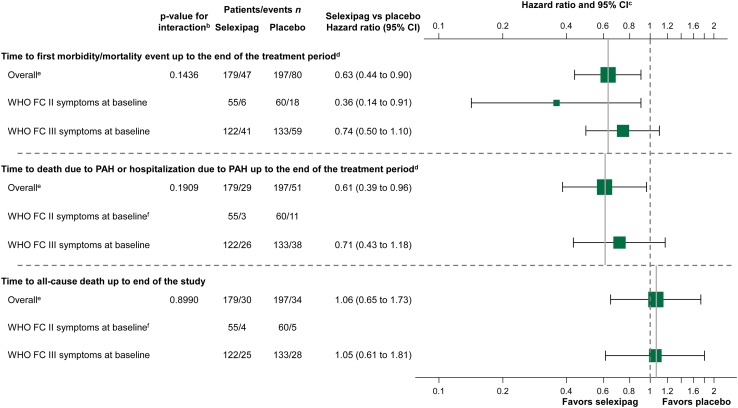

In patients receiving double oral combination therapy, selexipag reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality by 37% compared with placebo (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.44–0.90) (Figs. 1a, 2), consistent with the overall GRIPHON population [10]. As in the overall population [10], the most frequently reported primary endpoint events were those relating to morbidity, predominantly hospitalization due to PAH worsening and disease progression (accounting for 81.1% of events overall; Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality up to the end of treatment in patients receiving double combination therapy (with an ERA and PDE-5i) at baseline a overall, b with WHO FC II symptoms at baseline, and c with WHO FC III symptoms at baseline. Kaplan–Meier curves for the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality up to the end of treatment (defined for each patient as 7 days after the date of the last intake of selexipag or placebo) in the selexipag and placebo groups. The hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) for selexipag vs. placebo was 0.63 (0.44–0.90) in the overall group, 0.36 (0.14–0.91) in patients with WHO FC II symptoms, and 0.74 (0.50–1.10) in patients with WHO FC III symptoms. Following adjustment for baseline 6MWD, the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) was 0.37 (0.15–0.95) in patients with WHO FC II symptoms and 0.67 (0.45–1.01) in patients with WHO FC III symptoms. The analysis considered all available data; the Kaplan–Meier curve is truncated at 30 months because less than 10% of patients are at risk from this time-point onward. 6MWD 6-min walk distance, ERA endothelin receptor antagonist, PDE-5i phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, WHO FC World Health Organization functional class

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of time to event endpoints in patients receiving double combination therapya at baseline treated with selexipag vs. placebo. Hazard ratios and confidence intervals are unadjusted estimates. aReceiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor. bThe consistency of the treatment effect across subgroups was assessed using a test for interaction. An interaction p value > 0.01 indicates no heterogeneity and that the treatment effect is likely to be consistent across subgroups. cThe solid vertical line references the overall treatment effect, and the dotted vertical line represents a hazard ratio of 1. dTreatment period defined for each patient as 7 days after last intake of selexipag or placebo. eIncludes six patients with WHO FC IV symptoms at baseline. fHazard ratio and 95% CI not shown as there were too few events to perform meaningful statistical comparisons. CI confidence interval, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, WHO FC World Health Organization functional class

Table 2.

Summary of endpoints related to pulmonary arterial hypertension and death in patients receiving double combination therapya at baseline

| Endpoint | Overallb | WHO FC II symptoms at baseline | WHO FC III symptoms at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selexipag (N = 179) | Placebo (N = 197) | Selexipag (N = 55) | Placebo (N = 60) | Selexipag (N = 122) | Placebo (N = 133) | |

| Primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality up to the end of the treatment periodc | ||||||

| All events | 47 (26.3) | 80 (40.6) | 6 (10.9) | 18 (30.0) | 41 (33.6) | 59 (44.4) |

| Hospitalization for PAH worsening | 27 (15.1) | 43 (21.8) | 3 (5.5) | 8 (13.3) | 24 (19.7) | 33 (24.8) |

| Disease progression | 11 (6.1) | 22 (11.2) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (8.3) | 10 (8.2) | 16 (12.0) |

| Death from any cause | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 4 (3.3) | 2 (1.5) |

| Initiation of parenteral prostanoid therapy or long-term oxygen therapy for worsening PAH | 5 (2.8) | 10 (5.1) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.0) | 3 (2.5) | 7 (5.3) |

| Need for lung transplantation or balloon atrial septostomy for worsening PAH | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (0.75) |

| Secondary composite endpoint of death due to PAH or hospitalization for worsening of PAH up to the end of the treatment periodc | ||||||

| All events | 29 (16.2) | 51 (25.9) | 3 (5.5) | 11 (18.3) | 26 (21.3) | 38 (28.6) |

| Hospitalization for worsening of PAH | 29 (100) | 49 (96.1) | 3 (100) | 11 (100) | 26 (100) | 36 (94.7) |

| Death due to PAH | 0 | 2 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.3) |

Data are presented as n (%)

PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, WHO FC World Health Organization functional class

aReceiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor

bIncludes six patients with WHO FC IV symptoms at baseline

cTreatment period defined for each patient as 7 days after last intake of selexipag or placebo

When considering the symptom burden at baseline, there was a risk reduction with selexipag versus placebo of 64% (HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.14–0.91) in patients with WHO FC II symptoms and 26% (HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.50–1.10) in patients with WHO FC III symptoms (Figs. 1b, c, 2). When the baseline 6MWD was considered, the risk reduction was 63% (HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.15–0.95) in patients with WHO FC II symptoms and 33% (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.45–1.01) in patients with WHO FC III symptoms. Kaplan–Meier estimates (95% CI) of event-free survival at 12 months were 93.3% (80.6–97.8) and 79.3% (65.7–88.0) for selexipag- and placebo-treated patients with WHO FC II symptoms and 79.5% (70.2–86.1) and 70.1% (61.1–77.4) for selexipag- and placebo-treated patients with WHO FC III symptoms.

Secondary Endpoints

Death due to PAH or Hospitalization due to PAH Worsening

Treatment with selexipag resulted in a 39% reduction in the risk of death due to PAH or hospitalization due to PAH worsening compared with placebo (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.39–0.96), consistent with the overall GRIPHON population [10] (Fig. 2). The vast majority of these events were hospitalizations, as seen for the overall GRIPHON population (Table 2). Among the subgroup with WHO FC III symptoms at baseline, a similar trend was seen (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.43–1.18) (Table 2; Fig. 2), including following adjustment for 6MWD at baseline (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.38–1.05). There were fewer events in the selexipag (n = 3) arm compared with the placebo (n = 11) arm in patients with WHO FC II symptoms at baseline; however, there were too few events to perform meaningful statistical comparisons.

All-Cause Death up to the End of the Study

By the end of the study, 30 patients (16.8%) in the selexipag arm and 34 patients (17.3%) in the placebo arm had died (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.65–1.73) (Table S2 in the ESM; Fig. 2); this result was consistent with that in the overall GRIPHON population [10]. Analyzing by symptom burden at baseline, consistent results were seen for patients with WHO FC III symptoms (HR 1.05; 95% CI 0.61–1.81) (Table S2 in the ESM; Fig. 2), including after adjustment for 6MWD at baseline (HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.55–1.64). The number of deaths were similar in the selexipag (n = 4) and placebo (n = 5) arms in patients with WHO FC II symptoms; there were too few events for meaningful statistical comparisons.

Safety and Tolerability

A summary of safety and tolerability is provided in Table 3. Overall, 34 (19.0%) selexipag-treated patients and 15 (7.6%) placebo-treated patients discontinued their study regimen prematurely because of an AE. The most frequent AEs leading to discontinuation in the selexipag group (for events with a > 1% difference between selexipag and placebo) were headache (4.5%), diarrhea (4.5%), nausea (2.8%), asthenia (1.7%), and exertional dyspnea (1.1%). The proportion of patients who reported AEs was similar between the treatment groups, and the proportion who reported SAEs was lower for the selexipag-treated patients than for those treated with placebo (44.7 vs. 52.8%). When compared according to WHO FC at baseline, the proportion of selexipag-treated patients with an SAE, or who discontinued selexipag because of an AE, was lower for WHO FC II than for WHO FC III.

Table 3.

Summary of overall safety and tolerability in patients receiving double combination therapya at baseline

| Variable | Overallb | WHO FC II symptoms at baseline | WHO FC III symptoms at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selexipag (N = 179) | Placebo (N = 197) | Selexipag (N = 55) | Placebo (N = 60) | Selexipag (N = 122) | Placebo (N = 133) | |

| Exposure to double-blind treatment (weeks) | 63.1 (30.3–104.0) | 63.7 (38.0–102.1) | 66.3 (44.7–124.1) | 70.2 (46.0–101.0) | 61.3 (25.7–103.0) | 60.1 (31.7–104.3) |

| AEs, n | 1783 | 1693 | 496 | 462 | 1259 | 1181 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 AE | 175 (97.8) | 195 (99.0) | 53 (96.4) | 58 (96.7) | 120 (98.4) | 133 (100) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 SAE | 80 (44.7) | 104 (52.8) | 18 (32.7) | 29 (48.3) | 60 (49.2) | 72 (54.1) |

| Premature discontinuations due to an AE | 34 (19.0) | 15 (7.6) | 9 (16.4) | 5 (8.3) | 24 (19.7) | 10 (7.5) |

| AEc | ||||||

| Headache | 136 (76.0) | 76 (38.6) | 43 (78.2) | 18 (30.0) | 91 (74.6) | 57 (42.9) |

| Diarrhea | 100 (55.9) | 52 (26.4) | 32 (58.2) | 8 (13.3) | 66 (54.1) | 41.(30.8) |

| Nausea | 85 (47.5) | 49 (24.9) | 30 (54.5) | 12 (20.0) | 53 (43.4) | 36 (27.1) |

| Pain in jaw | 74 (41.3) | 20 (10.2) | 21 (38.2) | 3 (5.0) | 52 (42.6) | 16 (12.0) |

| PAH | 44 (24.6) | 74 (37.6) | 10 (18.2) | 21 (35.0) | 34 (27.9) | 50 (37.6) |

| Vomiting | 42 (23.5) | 21 (10.7) | 13 (23.6) | 7 (11.7) | 28 (23.0) | 13 (9.8) |

| Pain in extremity | 41 (22.9) | 20 (10.2) | 8 (14.5) | 4 (6.7) | 32 (26.2) | 16 (12.0) |

| Dyspnea | 36 (20.1) | 46 (23.4) | 7 (12.7) | 9 (15.0) | 29 (23.8) | 36 (27.1) |

| Flushing | 36 (20.1) | 16 (8.1) | 9 (16.4) | 5 (8.3) | 26 (21.3) | 11 (8.3) |

| Dizziness | 33 (18.4) | 34 (17.3) | 11 (20.0) | 11 (18.3) | 21 (17.2) | 22 (16.5) |

| URTI | 26 (14.5) | 29 (14.7) | 10 (18.2) | 10 (16.7) | 16 (13.1) | 19 (14.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 26 (14.5) | 28 (14.2) | 8 (14.5) | 7 (11.7) | 17 (13.9) | 21 (15.8) |

| Cough | 25 (14.0) | 31 (15.7) | 7 (12.7) | 9 (15.0) | 17 (13.9) | 21 (15.8) |

| Myalgia | 24 (13.4) | 8 (4.1) | 8 (14.5) | 1 (1.7) | 16 (13.1) | 7 (5.3) |

| Fatigue | 23 (12.8) | 23 (11.7) | 8 (14.5) | 6 (10.0) | 15 (12.3) | 17 (12.8) |

| Edema peripheral | 21 (11.7) | 43 (21.8) | 6 (10.9) | 9 (15.0) | 15 (12.3) | 30 (22.6) |

| Bronchitis | 21 (11.7) | 17 (8.6) | 7 (12.7) | 5 (8.3) | 14 (11.5) | 12 (9.0) |

| Right ventricular failure | 14 (7.8) | 27 (13.7) | 1 (1.8) | 8 (13.3) | 13 (10.7) | 17 (12.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (9.5) | 15 (7.6) | 8 (14.5) | 5 (8.3) | 9 (7.4) | 9 (6.8) |

| Arthralgia | 17 (9.5) | 20 (10.2) | 4 (7.3) | 4 (6.7) | 13 (10.7) | 16 (12.0) |

| Syncope | 16 (8.9) | 24 (12.2) | 3 (5.5) | 8 (13.3) | 13 (10.7) | 15 (11.3) |

| Decreased appetite | 10 (5.6) | 8 (4.1) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (3.8) |

| Asthenia | 9 (5.0) | 13 (6.6) | 3 (5.5) | 7 (11.7) | 6 (4.9) | 5 (3.8) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated

AE adverse event, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, SAE serious adverse event, URTI upper respiratory tract infection, WHO FC World Health Organization functional class

aReceiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor

bIncludes six patients with WHO FC IV symptoms at baseline

cAEs that occurred in > 10% of the patients in any study group during the double-blind period and up to 7 days after placebo or selexipag was discontinued

The PGI2-associated AEs reported during the titration and maintenance periods are shown in Table 4 and in Table S3 in the ESM. For selexipag-treated patients, PGI2-associated AEs generally occurred more frequently during the titration period of the study. In the selexipag group, the most commonly reported PGI2-associated AEs were headache, diarrhea, nausea, and jaw pain. The proportion of selexipag-treated patients who reported PGI2-associated AEs was comparable in those with WHO FC II and III symptoms.

Table 4.

Prostacyclin-associated adverse events in the titration and maintenance periods in patients receiving double combination therapya at baseline

| Variable | Titration period | Maintenance period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selexipag (N = 179) | Placebo (N = 197) | Selexipag (N = 157) | Placebo (N = 174) | |

| Exposure to double-blind treatment (weeks) | 12.4 (12.4–12.4) | 12.4 (12.4–12.4) | 59.7 (32.3–102.3) | 57.2 (39.6–94.6) |

| Patients with one or more prostacyclin-associated AE | 167 (93.3) | 110 (55.8) | 133 (84.7) | 105 (60.3) |

| AEb | ||||

| Headache | 132 (73.7) | 62 (31.5) | 88 (56.1) | 48 (27.6) |

| Diarrhea | 86 (48.0) | 28 (14.2) | 69 (43.9) | 39 (22.4) |

| Nausea | 70 (39.1) | 35 (17.8) | 49 (31.2) | 26 (14.9) |

| Pain in jaw | 70 (39.1) | 9 (4.6) | 55 (35.0) | 15 (8.6) |

| Pain in extremity | 36 (20.1) | 11 (5.6) | 30 (19.1) | 14 (8.0) |

| Vomiting | 35 (19.6) | 9 (4.6) | 17 (10.8) | 14 (8.0) |

| Flushing | 31 (17.3) | 11 (5.6) | 30 (19.1) | 10 (5.7) |

| Myalgia | 23 (12.8) | 8 (4.1) | 12 (7.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Dizziness | 22 (12.3) | 16 (8.1) | 21 (13.4) | 25 (14.4) |

| Arthralgia | 9 (5.0) | 13 (6.6) | 15 (9.6) | 12 (6.9) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 9 (5.0) | 2 (1.0) | 7 (4.5) | 5 (2.9) |

| Temporomandibular joint syndrome | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range)

AE adverse event

aReceiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor

bAEs that occurred in any of the patients in any study group during the double-blind period and up to 7 days after placebo or selexipag was discontinued. A patient with multiple occurrences of an AE during one treatment period is counted only once in the AE category for that treatment and period

Discussion

The GRIPHON trial provided the opportunity to evaluate the addition of a third oral agent in a population of patients whose disease was considered well-controlled with stable doses of double oral combination therapy. In this cohort of 376 patients, the risk of a composite primary endpoint morbidity/mortality event was ameliorated with the addition of selexipag to treatment with an ERA and a PDE-5i. The treatment effect was of a similar magnitude to that of the overall GRIPHON population [10] and was driven by a reduction in the number of PAH-related hospitalizations and disease progression events; as expected given the trial design, there was no effect on mortality.

The relatively large population of patients included in our analysis allowed the effect of selexipag to be assessed according to symptom burden at baseline. A benefit with selexipag was evident for patients with WHO FC II or III symptoms at baseline. Our data indicate that the relative reduction in the risk of morbidity/mortality events with selexipag versus placebo may be more pronounced in patients with WHO FC II symptoms, and a similar observation has been reported previously in PAH [4]. While these data raise the possibility that patients with less progressive disease respond better to therapy, caution is required to avoid over-interpretation of these subgroup analyses; the number of morbidity/mortality events in the WHO FC II group in this analysis was low (6% of all events in the study), the interaction p value of 0.1436 indicates consistency in the results, irrespective of WHO FC, and there was also no difference in the treatment response between patients with WHO FC II and III symptoms in the GRIPHON population as a whole [10].

In this analysis, our objective was to evaluate whether escalation of treatment from double to triple oral combination therapy is beneficial for patients with PAH. While our data indicate that selexipag provides an incremental benefit for patients already receiving an ERA and PDE-5i, they also show that a not insignificant proportion of patients receiving double combination therapy (i.e., randomized to placebo) and a somewhat lesser proportion of those receiving triple oral combination therapy (i.e., randomized to selexipag) do go on to experience disease progression events. These observations reflect the chronic and progressive nature of the disease. In line with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines for the management of PAH [2, 3], we advocate that escalation of therapy, including intravenous prostacyclin analogs, should be considered in patients who do not respond adequately while receiving combination therapy with two or more agents. In addition, we emphasize that, irrespective of the treatment regimen, be it monotherapy, double, or triple combination therapy, continual patient monitoring is essential to determine the optimal time for treatment escalation [2, 3]. PAH progresses differently in different patients, and while it may be possible to control disease progression in some patients with a number of oral agents, others may require parenteral prostacyclin therapy. Therefore, careful monitoring is essential to ensure these patients receive parenteral therapy when needed.

No safety concerns were identified when selexipag was received in combination with an ERA and PDE-5i. However, compared with the overall study population [10], we did observe more premature discontinuations due to an AE. This is likely due to the more intense treatment regimen in these patients. As the number of therapies being administered to patients with PAH increases, a greater number of side effects are expected to be observed. Indeed, a greater proportion of patients who were receiving double combination therapy at baseline reported SAEs and PGI2-related AEs compared with the overall population [10]; this was observed in both the placebo and the selexipag groups. Our findings indicate that, when administering three targeted therapies simultaneously, physicians should carefully monitor tolerability.

These were exploratory post hoc analyses; results should therefore be interpreted with some caution and are subject to certain limitations. The groups analyzed and the number of events were smaller than in the overall GRIPHON study, and the trial was not powered to demonstrate treatment effects in these groups. As a result, p values are not informative and are therefore not reported. As in the overall GRIPHON study, there was no difference between groups in all-cause death up to the end of the study. Whilst it is relevant to report the consistency of these data with those in the overall population, further interpretation of the HRs is not possible because of the low number of events and subsequent wide CIs, and the potential influence of cross-over, whereby patients who experienced a non-fatal primary endpoint event received open-label selexipag or standard of care, including intravenous prostacyclin analogs. In this subgroup, more than 50% of patients who experienced a non-fatal primary endpoint event received open-label selexipag. The effect of this cross-over on mortality has been estimated using modelling techniques, and the results for the overall GRIPHON population favor treatment with selexipag [12]. In our study, we analyzed patients according to baseline WHO FC symptoms. While WHO FC is one of the important prognostic markers in PAH [11], it is a subjective measure, and current guidelines recommend the use of multiple parameters to assess patients with PAH [2, 3]. To address the limitation of grouping patients according to a single parameter, we performed analyses adjusting for baseline 6MWD; these analyses yielded consistent results and support our initial observations.

Conclusions

The addition of selexipag to background double combination therapy in patients with PAH provided an incremental benefit similar to that seen in the overall GRIPHON population. Furthermore, the treatment response was consistent in patients with WHO FC II or III symptoms when administered in combination with double background therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sally Dempster, Ph.D., and Ruth Lloyd, Ph.D., employees of nspm Ltd, Meggen, Switzerland, for medical writing support and the patients and investigators for their contribution to the study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

This study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland). Sally Dempster, Ph.D., and Ruth Lloyd, Ph.D. (nspm Ltd, Meggen, Switzerland) provided medical writing support funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Channick has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, has served on an advisory board for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and Bayer, has received consultancy fees from Bayer, and has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and United Therapeutics. Dr. Chin has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer Healthcare, Gilead Sciences Inc., GeNO, NIH, United Therapeutics and SoniVie; and has received consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and United Therapeutics. Dr. Coghlan has received consultancy fees and honorarium from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and GlaxoSmithKline, honorarium from Bayer, and congress fees from MSD. Dr. Di Scala is a full-time employee of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Professor Gaine has served as a steering committee member for and received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received speaker fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, and United Therapeutics; has received advisory board fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, and Daiichi-Sankyo; has received travel support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Daiichi-Sankyo; and has served on a data safety monitoring board for GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and United Therapeutics. Prof. Galiè has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received research grants and consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; and has received speaker fees from MSD. Prof. Ghofrani has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received advisory board and speaker fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer; has received consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, Bellerophon Pulse technologies, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer; has received travel support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer; and has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Prof. Hoeper has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received lecture and consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, and Pfizer; has received consultancy fees from Gilead; and has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Prof. Lang has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received speaker fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals, and Bayer. Prof. McLaughlin has received consultancy fees from and served as an advisory board member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Gilead, Ikaria, and United therapeutics; has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, and Gilead; has received personal fees from Steadymed Therapeutics and St Jude Medical; has received travel support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Gilead, Ikaria, and United Therapeutics; and has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Eiger, Gilead, Ikaria, Novartis, and SoniVie Ltd. Dr Preiss is a full-time employee of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Prof. Rubin has received grant support from and served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has received consultancy fees and travel support from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Arena Pharmaceuticals, GeNO Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Karos Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and SoniVie Ltd; and has three patents issued. Prof. Simonneau has served as a steering committee member for and received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and Bayer; has received speaker and consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, and Pfizer. Prof. Sitbon has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd; has served as an advisory board member for and received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, and MSD; has received consultancy fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, and United Therapeutics; has received speaker fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, and United Therapeutics; and has received writing assistance from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd and GlaxoSmithKline. Prof. Tapson has served as a steering committee member for Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, and United Therapeutics; has received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, BIO2 Medical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Inari, Janssen, EKOS/BTG, Arena, Reata, Eiger, and United Therapeutics; has received consulting fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Bayer, BiO2 Medical, United Therapeutics, Janssen, Arena, Reata, and Vwave medical; and has received lecture honorarium from Actelion, EKOS/BTG, Gilead Sciences, Bayer, and Janssen.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40256-017-0262-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.McLaughlin VV, Suissa S. Prognosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the power of clinical registries of rare diseases. Circulation. 2010;122:106–108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.963983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Respir J. 2015;46:903–975. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galiè N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:834–844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, et al. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:809–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50. 10.1183/13993003.00889-2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McGoon MD, Miller DP. REVEAL: a contemporary US pulmonary arterial hypertension registry. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:8–18. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00008211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin KM, Channick R, Kim NH, et al. OPUS registry: treatment patterns with macitentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A2299. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sitbon O, Jais X, Savale L, et al. Upfront triple combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1691–1697. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00116313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, et al. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2522–2533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin VV, Gaine S, Howard LS, et al. Treatment goals of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D73–D81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Report: Uptravi (selexipag). 2016. Accessed Apr 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.