Abstract

Objective

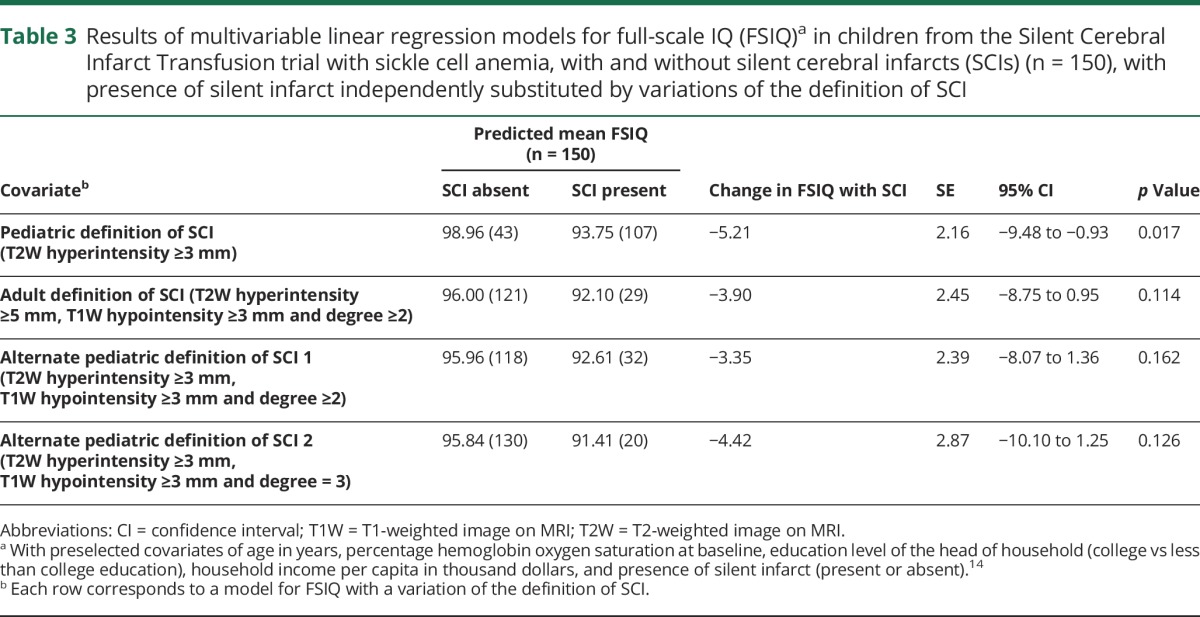

To evaluate whether application of the adult definition of silent cerebral infarct (SCI) (T2-weighted hyperintensity ≥5 mm with corresponding T1-weighted hypointensity on MRI) is associated with full-scale IQ (FSIQ) loss in children with sickle cell anemia (SCA), and if so, whether this loss is greater than that of the reference pediatric definition of SCI (T2-weighted hyperintensity ≥3 mm in children on MRI; change in FSIQ −5.2 points; p = 0.017; 95% confidence interval [CI] −9.48 to −0.93).

Methods

Among children with SCA screened for SCI in the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion trial, ages 5–14 years, a total of 150 participants (107 with SCIs and 43 without SCIs) were administered the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. A multivariable linear regression was used to model FSIQ in this population, with varying definitions of SCI independently substituted for the SCI covariate.

Results

The adult definition of SCI applied to 27% of the pediatric participants with SCIs and was not associated with a statistically significant change in FSIQ (unstandardized coefficient −3.9 points; p = 0.114; 95% CI −8.75 to 0.95), with predicted mean FSIQ of 92.1 and 96.0, respectively, for those with and without the adult definition of SCI.

Conclusions

The adult definition of SCI may be too restrictive and was not associated with significant FSIQ decline in children with SCA. Based on these findings, we find no utility in applying the adult definition of SCI to children with SCA and recommend maintaining the current pediatric definition of SCI in this population.

The radiologic definition of silent cerebral infarct (SCI) is different among pediatric vs adult populations with sickle cell anemia (SCA).1,2 The more restrictive definition of SCI in adults with SCA, with respect to the greater minimum size of the T2-weighted (T2W) hyperintensity (≥5 vs ≥3 mm) and the corresponding T1-weighted (T1W) hypointensity on MRI,1 has not been applied to children with SCA (table e-1, links.lww.com/WNL/A44).

The pediatric definition of SCI (from the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion [SIT] trial) is associated with full-scale IQ (FSIQ) decline of 5.2 points (p = 0.017).3 Increased infarct size may be associated with greater magnitude of cognitive deficit in children with SCA, based on the observations of poorer neuropsychological functioning and larger average lesion size in those with overt strokes vs SCIs.4–6 In this cross-sectional, secondary analysis of the SIT trial, we therefore tested the main hypothesis that application of the adult definition of SCI is associated with FSIQ decline in children with SCA, and if so, whether the decline is greater than that of the pediatric definition of SCI.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), the degree of the T1W hypointensity has been shown to improve clinical–radiologic correlations of lesion volume with cognitive morbidity over the presence of T2W hyperintensities alone.7–11 Therefore, we tested the secondary hypothesis that the presence of a corresponding T1W hypointensity is associated with FSIQ decline in children with SCA, and if so, whether the decline is greater than that of the reference pediatric definition of SCI.

Methods

Study design and participants

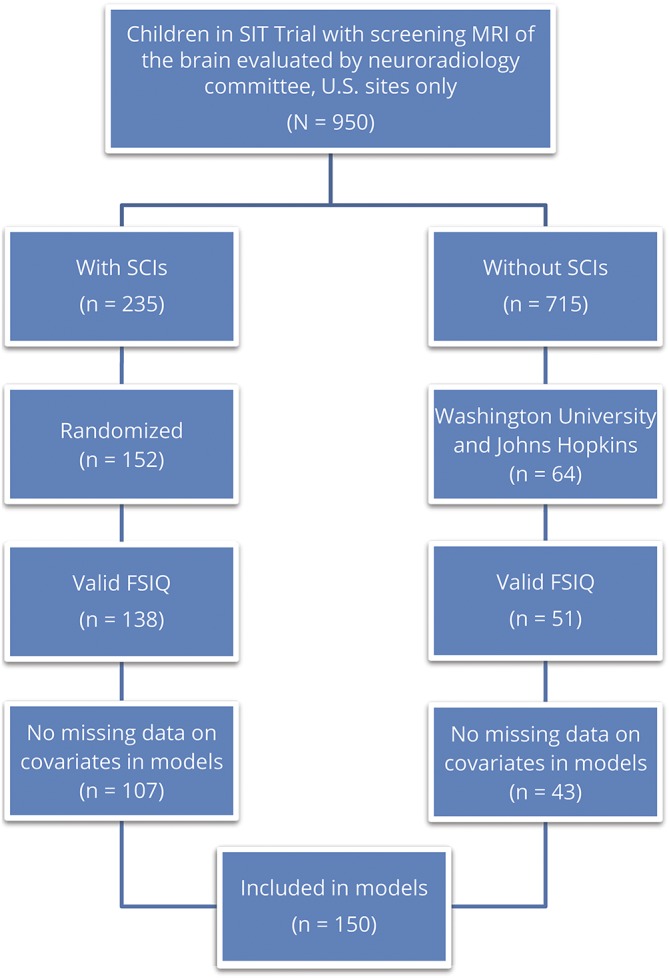

The SIT trial was a randomized, single-blind, prospective clinical trial conducted at 29 clinical centers across North America and Europe between 2003 and 2013, and demonstrated that regular blood transfusion therapy significantly reduced the incidence of recurrent cerebral infarcts in children with SCA and SCIs.2 A secondary analysis by King et al.3 was performed in a multicenter, cross-sectional study at 19 of 29 sites in the SIT trial, and included a pooled meta-analysis of 10 studies (including the SIT trial) comparing the mean difference in FSIQ between children with SCA, with and without SCIs, demonstrating an average 5-point decrease in FSIQ in those with SCIs. The designs and methods of both studies have been published previously.2,3 Participants included children between 5 and 14 years of age with confirmed diagnosis of SCA (hemoglobin SS or hemoglobin Sβ0 thalassemia) and no history of overt strokes or seizures. MRIs of the brain were reviewed in a total of 196 children with SCA, SCIs, and normal transcranial Doppler (TCD) velocities who were randomly allocated to either transfusion or observation groups in the SIT trial; of these, 152 children were from US sites and received baseline cognitive assessments. A total of 150 children with SCA were included in our final analysis, including 107 with SCIs and 43 without SCIs from the SIT trial who had complete cognitive assessments at baseline and no missing data on key covariates (figure 1).

Figure 1. Children from the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion (SIT) trial with sickle cell anemia (SCA), with and without silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs), included in this study.

FSIQ = full-scale IQ.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The SIT trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00072761) and ISRCTN.org (ISRCTN52713285).2 The SIT trial2 and secondary analysis by King et al.3 were approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions. Informed consent and assent were obtained prior to enrollment.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome in this study was defined as FSIQ (a secondary outcome in the SIT trial) and measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence or Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–III for children <6 years of age (n = 11) at participants' baseline state of health.

Definitions

T1W hypointensity scoring

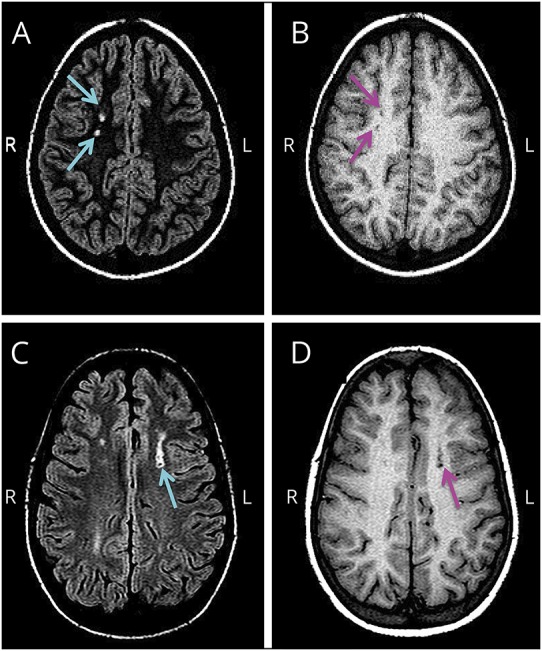

We developed a scoring system for the evaluation of T1W hypointensities, with the following 4 degrees in order of decreasing intensity: (0) not visible, or isointense to surrounding white matter; (1) hypointense to surrounding white matter but hyperintense to surrounding gray matter (GM); (2) isointense to surrounding GM; and (3) hypointense to surrounding GM. Degrees ≥2 were considered to qualify a T1W hypointensity (figure 2). Furthermore, lesions ≥3 mm were considered reliably detectible in our study by the neuroradiologist.12

Figure 2. Silent cerebral infarct (SCI) lesions on T2-weighted (T2W) and T1-weighted (T1W) MRI.

The following are corresponding T2W and T1W axial MRI images (A–D) from 2 children randomly allocated in the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion (SIT) trial with sickle cell anemia (SCA), SCIs, and normal transcranial Doppler (TCD) velocities. (A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) T2W axial MRI with hyperintensities indicated by turquoise arrows. (B) Corresponding T1W axial MRI with hypointensities, degree = 2 (isointense to surrounding gray matter [GM]), indicated by magenta arrows. (C) FLAIR T2W axial MRI with hyperintensity indicated by turquoise arrow. (D) Corresponding T1W axial MRI with hypointensity, degree = 3 (hypointense to surrounding GM), indicated by magenta arrow.

Variations of the definition of SCI

Based on the scoring system created to evaluate T1W hypointensities, 3 components were considered for inclusion in our alternate definitions of SCI: (1) T2W hyperintensity measuring ≥3 or 5 mm in greatest dimension on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) axial MRI; (2) corresponding T1W hypointensity with degree ≥2 or 3 (figure 2); and (3) corresponding T1W hypointensity measuring ≥3 mm in greatest dimension. In addition to the primary and secondary hypotheses, we explored 8 other possible combinations of these criteria (based on the presence of at least 1, 2, or 3 criteria) (table e-2, links.lww.com/WNL/A44).

Adult vs pediatric definitions of SCI in SCA

The definition of SCI in both children and adults with SCA requires the absence of any historic or current focal neurologic deficit consistent with the anatomic location of the lesion.1,2 The adult definition of SCI in SCA, described by Vichinsky et al.,1 refers to a hyperintensity on brain MRI measuring ≥5 mm in greatest linear dimension on the T2W image as well as the proton density–weighted image, with a corresponding hypointensity on the T1W image. Due to the lack of specificity in this reference definition with regard to either degree or size of the corresponding T1W hypointensity, we considered those lesions either isointense or hypointense to the surrounding GM on MRI (degree ≥ 2) (figure 2) and measuring ≥3 mm in greatest linear dimension on the T1W image to qualify for the presence of a hypointensity.

The SIT trial definition of SCI in children with SCA was developed by the Washington University sickle cell disease stroke team, and consists of an infarct-like lesion on brain MRI measuring ≥3 mm along the greatest linear dimension and visible in at least 2 planes of FLAIR T2W images (axial and coronal), without corresponding neurologic deficits.2,13 Central adjudication of the presence or absence of SCIs was determined by a committee of neuroradiologists; the definition of SCI was independently determined by a committee of pediatric neurologists, due to the requirement of no focal neurologic deficit consistent with the site of the infarct-like lesion.2 For the purpose of testing our secondary hypothesis (that presence of a corresponding T1W hypointensity in the pediatric definition of SCI is associated with FSIQ decline in children with SCA), we developed alternate pediatric definitions of SCI that, in addition to the above, include the presence of a corresponding hypointensity with degrees at least isointense or hypointense to the surrounding GM (degree ≥2 or 3, respectively) (figure 2) and measuring ≥3 mm in greatest linear dimension on the T1W image to be reliably detectible.

MRI review and interpretation

MRIs of the brain at baseline for the randomly allocated children in the SIT trial (n = 196) were viewed using the iSite PACS system (Philips Healthcare Informatics, Foster City, CA). Baseline MRIs referred to those performed at either screening or prerandomization. Lesions were previously labeled on FLAIR T2W axial MRI for length (mm in greatest dimension) measurements by the SIT trial neuroradiologists.2 Lengths of all visible T1W hypointensities were measured using the ruler tool on iSite. T1W axial MRI was used to assess corresponding T1W hypointensities unless the T1W axial image was missing (n = 46); the T1W sagittal image was substituted for assessment in these cases. A T1W hypointensity was determined to correspond to the equivalent location on baseline MRI of the brain as the T2W hyperintensity using localizer or scout line tools on iSite.

N.A.C. assessed each SCI lesion, which by definition in the SIT trial consisted of a hyperintensity measuring ≥3 mm on the FLAIR T2W image,2 according to the following criteria: (1) hyperintensity ≥5 mm in length on the FLAIR T2W image (present or absent); (2) corresponding hypointensity degree on the T1W image (0, 1, 2, or 3, as defined above); and (3) corresponding hypointensity ≥3 mm in length on the T1W image (present or absent). T1W hypointensity degree was reassessed for all lesions on 5 blinded passes. Degrees for 43 of 587 lesions (7%) were modified on either the second or third pass. The neuroradiologist (R.C.M.) reviewed any equivocal cases and provided final consensus for 173 of 587 lesions (29%).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were analyzed using t tests, with the Mann-Whitney U test used for variables with unequal variance or skewed distributions. Categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 test. A multivariable linear regression was used to model FSIQ, with preselected covariates of age, percentage hemoglobin oxygen saturation at baseline, education level of the head of household (college vs less than college education), household income per capita in thousand dollars, and SCI (present or absent) (using the same methodology as the one employed in a previous study).3 Varying definitions of SCI were independently substituted for the reference pediatric definition of SCI in the model. We considered p < 0.05 to be statistically significant for an association with FSIQ and did not adjust for multiple comparisons. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used to perform all analyses.

Results

Demographic and clinical features of children with SCA

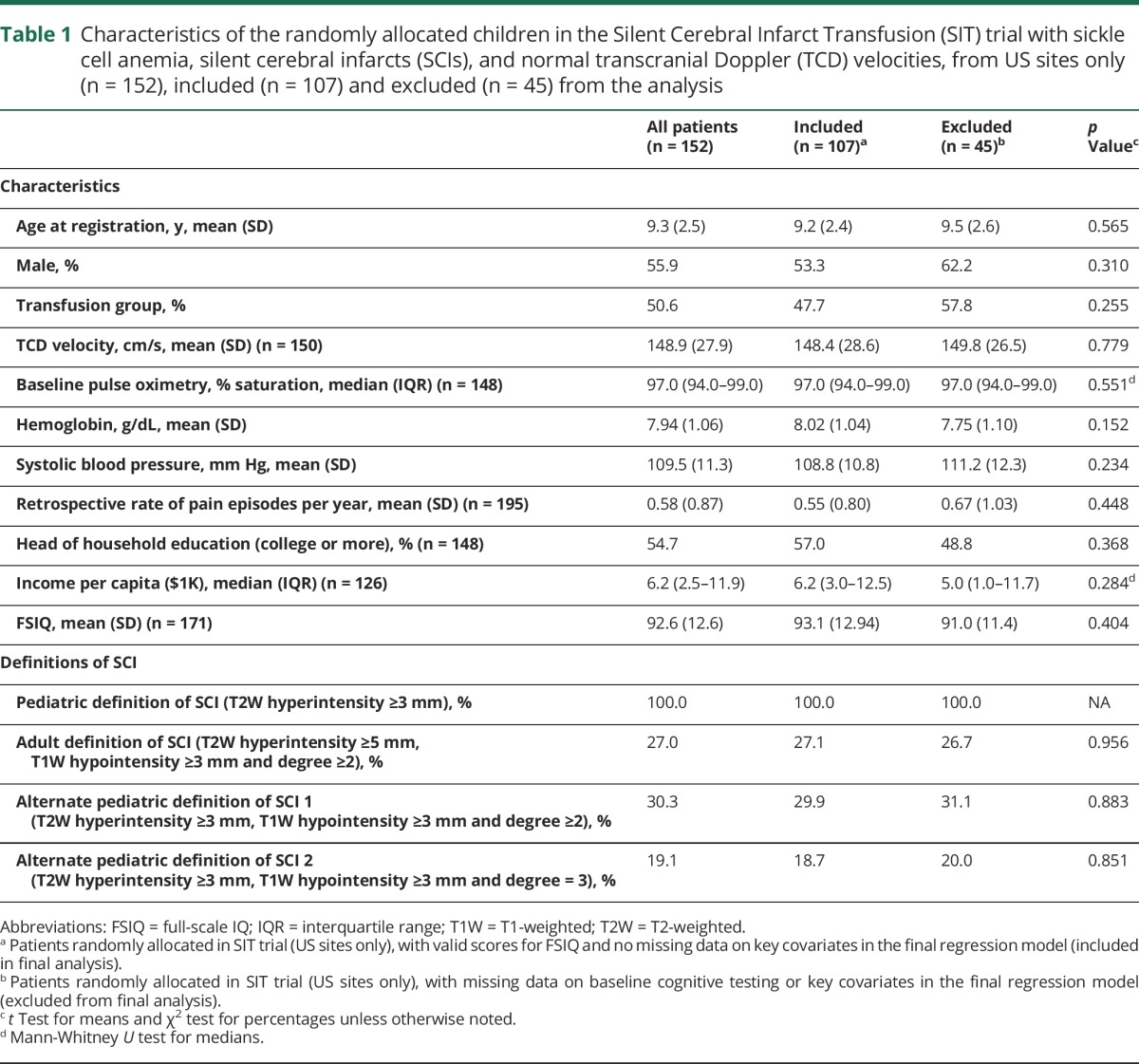

Baseline MRIs of the brain were reviewed and interpreted for 196 children randomized in the SIT trial with a total of 587 SCI lesions (mean 3 lesions per patient; range 1–17 lesions per patient). The demographics, clinical features, and prevalence of the varying definitions of SCI in the children with SCA, SCIs, and normal TCD velocities who were randomly allocated in the SIT trial, from US sites only (n = 152), are shown in table 1, along with a comparison of the characteristics between the 107 children included and 45 children excluded from the final analysis. There were no differences in features between the children included and excluded from final analysis. The prevalences for all 12 variations of pediatric or adult definitions of SCI in the 196 children with SCA, SCIs, and normal TCD velocities (randomized from US and non-US sites in the SIT trial) are shown in table e-2 (links.lww.com/WNL/A44).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the randomly allocated children in the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion (SIT) trial with sickle cell anemia, silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs), and normal transcranial Doppler (TCD) velocities, from US sites only (n = 152), included (n = 107) and excluded (n = 45) from the analysis

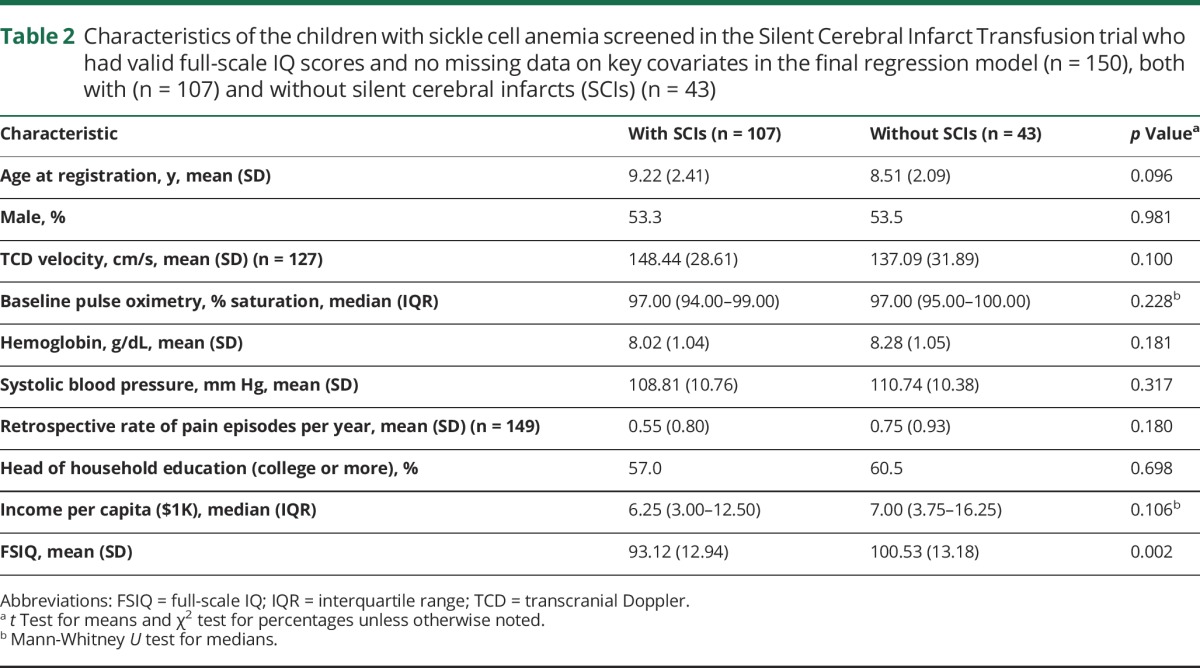

The demographic and clinical features of the 150 children with SCA, with and without SCIs (107 and 43, respectively), who were included in the final regression models for FSIQ are shown in table 2. Mean FSIQ was the only difference between the groups with and without SCIs (p = 0.002). The results of the regression models for all 12 variations of pediatric or adult definitions of SCI in the 150 children with SCA, with and without SCIs, are shown in table e-3 (links.lww.com/WNL/A44).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the children with sickle cell anemia screened in the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion trial who had valid full-scale IQ scores and no missing data on key covariates in the final regression model (n = 150), both with (n = 107) and without silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs) (n = 43)

The adult definition of SCI was not associated with FSIQ decline in children with SCA

In the 150 children with SCA with and without SCIs (n = 107 and n = 43, respectively) included in the regression model for FSIQ, the reference pediatric definition of SCI (T2W hyperintensity ≥3 mm) was associated with FSIQ decline of 5.21 points (p = 0.017; 95% confidence interval [CI] −9.48 to −0.93) with predicted mean FSIQ of 93.8 and 99.0, respectively, for those with and without SCIs (table 3). The adult definition of SCI (T2W hyperintensity ≥5 mm, T1W hypointensity ≥3 mm and degree ≥2) yielded far fewer classified as having SCI (n = 29); this categorization resulted in a change in FSIQ of −3.90 points (p = 0.114; 95% CI −8.75 to 0.95) with predicted mean FSIQ of 92.1 and 96.0, respectively, for those with and without the adult definition of SCI (table 3).

Table 3.

Results of multivariable linear regression models for full-scale IQ (FSIQ)a in children from the Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion trial with sickle cell anemia, with and without silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs) (n = 150), with presence of silent infarct independently substituted by variations of the definition of SCI

Addition of a corresponding T1W hypointensity was not associated with FSIQ decline in children with SCA

Our alternate pediatric definitions of SCI (T2W hyperintensity ≥3 mm, T1W hypointensity ≥3 mm and degree ≥2 or 3) also yielded far fewer classified as having SCI (n = 32 and n = 20, respectively); these categorizations resulted in changes in FSIQ of −3.35 points (p = 0.162; 95% CI −8.07 to 1.36) and −4.42 points (p = 0.126; 95% CI −10.10 to 1.25), respectively (table 3). The predicted mean FSIQ was 92.6 and 96.0, respectively, for those with and without the first alternate pediatric definition of SCI and 91.4 and 95.8, respectively, for those with and without the second alternate pediatric definition (table 3).

Discussion

SCIs are the most common form of neurologic disease in children with SCA,14 occurring in 39% by age 18 with no plateau in prevalence from early childhood through young adulthood.15–17 Untreated children with SCA, SCIs, and normal TCD velocities have a high rate of new cerebral infarcts with 4.8 events per 100 patient-years2 (a rate of strokes similar to that of untreated atrial fibrillation in the general population).16 The neurocognitive burden of SCIs in children with SCA includes impairment in global intellectual function as reflected by lower cognitive test scores, poor academic attainment, and FSIQ decline of approximately 5 points.3,4,18–20

The radiologic definition of SCI differs between children and adults with SCA, primarily based on size (≥3 vs ≥5 mm in greatest dimension on the T2W MRI, respectively) and the presence of a corresponding T1W hypointensity (in adults).1,2 With respect to the greater size of the lesion, the adult definition may provide some distinction from the normal accumulation of SCIs associated with aging in the general population.14 Despite the knowledge of an association between increased size of SCIs and the magnitude of cognitive impairment,4–6 we did not find evidence that the adult definition of SCI is associated with increased cognitive morbidity, as measured by FSIQ decline. The adult definition of SCI only applies to 27% of the pediatric population with SCA and SCIs. As a consequence, although the predicted FSIQ for those meeting the adult definition (92.1) is somewhat lower than for those meeting the pediatric definition (93.8), the grouping of patients meeting the pediatric definition of SCI (but not the adult definition) in the same comparison category as those without SCIs leads to reduced effect of the adult definition of SCI on FSIQ. Based on these findings, we find no utility in applying the restrictive adult definition of SCI to children with SCA and recommend maintaining the current SIT trial definition of SCI in this population.

As a secondary hypothesis, we investigated whether the presence of a corresponding T1W hypointensity, defined as at least isointense or hypointense to the surrounding GM (degree ≥2 or 3) and measuring ≥3 mm on MRI, contributes to FSIQ decline in supplementing the pediatric definition of SCI in children with SCA. In our study, we found that such an addition to the pediatric definition of SCI does not increase the magnitude of FSIQ decline in children with SCA. As with the adult definition, the alternate pediatric definitions apply to a smaller subgroup, and so their effects on FSIQ are reduced. The discrepancy between the findings of this study and those of MS studies regarding the association of the T1W hypointensities with increased cognitive morbidity may be due to differences in pathophysiology, demographics, and measures of cognitive morbidity between children with SCA and SCIs and individuals with MS.2,10,14,21

The following limitations exist in this study: first, scoring of the degree of T1W hypointensities was performed qualitatively based on visual examination, which is inherently more susceptible to intrarater and scan-to-scan variation than quantitative methods. However, all scans were independently reviewed on multiple passes, without consideration of prior scores, and scores were modified on subsequent passes in only 7% (43 of 587) of the total lesions. For the purpose of standardization and additional validation in potential future studies involving the radiologic definition of SCI in populations with SCA, quantitative techniques (such as T1-relaxation time threshold and magnetization transfer ratio) that have gained prominence in comparable MS studies8,22–25 may be considered for implementation. Second, evaluation of the size of SCI lesions in this study was based on length in one dimension and not on volume as in other studies involving the association between SCIs and cognitive morbidity in children with SCA.26,27 However, the main purpose of this study was to compare the adult vs pediatric definition of SCI (which differ primarily based on length in greatest dimension of T2W hyperintensities) on the association with FSIQ decline in children with SCA.

We have demonstrated that in children with SCA, application of the adult definition of SCI may be too restrictive and is therefore not associated with FSIQ decline. We have similarly shown that in children with SCA, the addition of a corresponding T1W hypointensity to the pediatric definition of SCI is not associated with FSIQ decline. While these results suggest there may be no rationale in changing the current pediatric definition of SCI in children with SCA, which is associated with FSIQ decline of approximately 5 points, this does not extend to any implications for the definition of SCI in adults with SCA, which may benefit from clarification of the minimum size and degree of corresponding T1W hypointensities.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the members of the DeBaun Laboratory and Vanderbilt-Meharry Center of Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease (Djamila L. Ghafuri, Tilicia Mayo-Gamble, Shruti Chaturvedi, Robert Cronin, and Shaina W. Johnson) for critically reviewing and editing the manuscript for nonintellectual content.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FSIQ

full-scale IQ

- GM

gray matter

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- SCA

sickle cell anemia

- SCI

silent cerebral infarct

- SIT

Silent Cerebral Infarct Transfusion

- T1W

T1-weighted

- T2W

T2-weighted

- TCD

transcranial Doppler

Footnotes

Editorial, page 105

Author contributions

Natasha A. Choudhury: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Michael R. DeBaun: study concept and design, study supervision, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Mark Rodeghier: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Allison A. King: study design, acquisition of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. John J. Strouse: study design, acquisition of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Robert C. McKinstry: study concept and design, acquisition of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content.

Study funding

Supported by the Vanderbilt Medical Scholars Program at Vanderbilt University (N.A.C.); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Rockville, Maryland (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: U01 NS042804) (M.R.D.); and Burroughs Wellcome Foundation (M.R.D.).

Disclosure

N. Choudhury, M. DeBaun, and M. Rodeghier report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. King received funding from the NHLBI (K23HL079073) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to support this work. J. Strouse received funding from the NHLBI (1K23HL078819), the American Society of Hematology, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to support this work. R. McKinstry reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Vichinsky EP, Neumayr LD, Gold JI, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction and neuroimaging abnormalities in neurologically intact adults with sickle cell anemia. JAMA 2010;303:1823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, et al. Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King AA, Strouse JJ, Rodeghier MJ, et al. Parent education and biologic factors influence on cognition in sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 2014;89:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong FD, Thompson RJ Jr, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease: Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins KE, Hewes SKM, Connelly A, et al. Cognitive deficits associated with frontal-lobe infarction in children with sickle cell disease. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pegelow CH, Macklin EA, Moser FG, et al. Longitudinal changes in brain magnetic resonance imaging findings in children with sickle cell disease. Blood 2002;99:3014–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truyen L, van Waesberghe JH, van Walderveen MA, et al. Accumulation of hypointense lesions (“black holes”) on T1 spin-echo MRI correlates with disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1996;47:1469–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thaler C, Faizy T, Sedlacik J, et al. T1-thresholds in black holes increase clinical-radiological correlation in multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tam RC, Traboulsee A, Riddehough A, Sheikhzadeh F, Li DK. The impact of intensity variations in T1-hypointense lesions on clinical correlations in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2011;17:949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simioni S, Amaru F, Bonnier G, et al. MP2RAGE provides new clinically-compatible correlates of mild cognitive deficits in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2014;261:1606–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Walderveen MA, Barkhof F, Hommes OR, et al. Correlating MRI and clinical disease activity in multiple sclerosis: relevance of hypointense lesions on short-TR/short-TE (T1-weighted) spin-echo images. Neurology 1995;45:1684–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liem RI, Liu J, Gordon MO, et al. Reproducibility of detecting silent cerebral infarcts in pediatric sickle cell anemia. J Child Neurol 2014;29:1685–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glauser TA, Siegel MJ, Lee BC, DeBaun MR. Accuracy of neurologic examination and history in detecting evidence of MRI-diagnosed cerebral infarctions in children with sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. J Child Neurol 1995;10:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBaun MR, Armstrong FD, McKinstry RC, Ware RE, Vichinsky E, Kirkham FJ. Silent cerebral infarcts: a review on a prevalent and progressive cause of neurologic injury in sickle cell anemia. Blood 2012;119:4587–4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernaudin F, Verlhac S, Arnaud C, et al. Chronic and acute anemia and extracranial internal carotid stenosis are risk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. Blood 2015;125:1653–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeBaun MR, Kirkham FJ. Central nervous system complications and management in sickle cell disease. Blood 2016;127:829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassim AA, Pruthi S, Day M, DeBaun MR, Jordan LC. Silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral aneurysms are prevalent in adults with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2016;127:2038–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernaudin F, Verlhac S, Freard F, et al. Multicenter prospective study of children with sickle cell disease: radiographic and psychometric correlation. J Child Neurol 2000;15:333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, Enos L, Gallagher D, et al. Neuropsychologic performance in school-aged children with sickle cell disease: a report from the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr 2001;139:391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan AM, Kirkham FJ, Prengler M, et al. An exploratory study of physiological correlates of neurodevelopmental delay in infants with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol 2006;132:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Walderveen MA, Kamphorst W, Scheltens P, et al. Histopathologic correlate of hypointense lesions on T1-weighted spin-echo MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1998;50:1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonkman LE, Soriano AL, Amor S, et al. Can MS lesion stages be distinguished with MRI? A postmortem MRI and histopathology study. J Neurol 2015;262:1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brex PA, Parker GJM, Leary SM, et al. Lesion heterogeneity in MS: a study of the relations btw appearances on T1 weighted images, T1 relaxation times, and metabolite concentrations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loevner LA, Grossman RI, McGowan JC, Ramer KN, Cohen JA. Characterization of multiple sclerosis plaques with T1-weighted MR and quantitative magnetization transfer. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:1473–1479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiehle JF Jr, Grossman RI, Ramer KN, Gonzalez-Scarano F, Cohen JA. Magnetization transfer effects in MR-detected multiple sclerosis lesions: comparison with gadolinium-enhanced spin-echo images and non-enhanced T1-weighted images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schatz J, White DA, Moinuddin A, Armstrong M, DeBaun MR. Lesion burden and cognitive morbidity in children with sickle cell disease. J Child Neurol 2002;17:891–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schatz J, Craft S, Koby M, et al. Neuropsychologic deficits in children with sickle cell disease and cerebral infarction: role of lesion site and volume. J Child Neuropsych 1999;5:92–103. [Google Scholar]