ABSTRACT

Members of the genus Caldicellulosiruptor have the ability to deconstruct and grow on lignocellulosic biomass without conventional pretreatment. A genetically tractable species, Caldicellulosiruptor bescii, was recently engineered to produce ethanol directly from switchgrass. C. bescii contains more than 50 glycosyl hydrolases and a suite of extracellular enzymes for biomass deconstruction, most prominently CelA, a multidomain cellulase that uses a novel mechanism to deconstruct plant biomass. Accumulation of cellobiose, a product of CelA during growth on biomass, inhibits cellulase activity. Here, we show that heterologous expression of a cellobiose phosphorylase from Thermotoga maritima improves the phosphorolytic pathway in C. bescii and results in synergistic activity with endogenous enzymes, including CelA, to increase cellulolytic activity and growth on crystalline cellulose.

IMPORTANCE CelA is the only known cellulase to function well on highly crystalline cellulose and it uses a mechanism distinct from those of other cellulases, including fungal cellulases. Also unlike fungal cellulases, it functions at high temperature and, in fact, outperforms commercial cellulase cocktails. Factors that inhibit CelA during biomass deconstruction are significantly different than those that impact the performance of fungal cellulases and commercial mixtures. This work contributes to understanding of cellulase inhibition and enzyme function and will suggest a rational approach to engineering optimal activity.

KEYWORDS: consolidated bioprocessing, biomass deconstruction, cellobiose phosphorylase, Caldicellulosiruptor

INTRODUCTION

Members of the genus Caldicellulosiruptor are the most thermophilic cellulolytic bacteria so far described (1). Their ability to grow efficiently on lignocellulosic biomass without conventional pretreatment and recent advances in engineering strains for ethanol production make these organisms of special interest for consolidated bioprocessing. Cellulolytic ability in members of this genus varies and correlates with the presence of CelA, the most abundant enzyme in its exoproteome (2). One of the major products of the GH48 exoglucanase domain is cellobiose (3). Cellulase activity and fermentation ability on crystalline cellulose have been shown to be inhibited by cellobiose (1, 4), and previous studies have shown that accumulation of high concentrations of cellobiose and, to a lesser extent, cellotriose are present in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii digests of crystalline cellulose after 90 h of incubation (1). This inhibition by cellobiose accumulation represents a major limitation to biomass deconstruction by C. bescii for consolidated bioprocessing (CBP).

In most cellulolytic organisms, β-glucosidase activity is essential for the efficient utilization of cellobiose, the primary product of exoglucanase activity, and longer oligosaccharides (5), but no extracellular β-glucosidase is present in the C. bescii genome (6, 7). Motivated by the fact that the addition of exogenous purified β-glucosidase from Thermotoga maritima substantially improved the performance of CelA on Avicel (4) in vitro, we recently reported the cloning and expression of a β-glucosidase from Acidothermus cellulolyticus in C. bescii (8). This led to a significant but surprisingly modest increase in growth on Avicel. We suggested that this might be due to a metabolic burden in these anaerobic bacteria caused by β-glucosidase overexpression and most importantly to the fact that import of longer oligosaccharides is much more energetically favorable than importation of glucose (9). Oligosaccharides require a single ATP for transport and result in the import of several sugar moieties. Transport of individual sugars is also ATP dependent (7) and required one ATP per glucose moiety for transport, resulting in a greater energetic burden. Indeed, β-glucosidase hydrolyzes cellobiose into two glucose molecules, and each must be phosphorylated to allow utilization. This is likely energetically unfavorable for strict anaerobes.

Cellobiose phosphorylase hydrolyzes cellobiose and simultaneously phosphorylates one of the glucose molecules with an inorganic phosphate group, yielding one glucose molecule and one glucose 1-phosphate (G1P) molecule without depleting ATP levels. Both glucose and G1P molecules are further metabolized through glycolysis. Since one glucose molecule is already phosphorylated before entering the glycolytic pathway, the expression of a cellobiose phosphorylase in C. bescii should be energetically advantageous compared to the expression of a β-glucosidase alone (10, 11). In addition, the rate of phosphorolysis greatly exceeds the rate of hydrolysis, indicating the possible metabolic advantage of this reaction (12). The scarcity of ATP under anaerobic growth conditions may in fact be a crucial factor in the preponderance of the phosphorolytic pathways in obligate anaerobic bacteria (13, 14). While C. bescii contains putative intracellular cellobiose/cellodextrin phosphorylases (Cbes_0459 and Cbes_0460) in its genome, the fact that high concentrations of cellobiose accumulate after 90 h of incubation of C. bescii on crystalline cellulose (1) suggested that the activity of the native C. bescii cellobiose/cellodextrin phosphorylases is not sufficient and that overexpression of cellobiose phosphorylase in C. bescii might improve both cellulolytic activity and growth on cellulosic substrates. In this study, we constructed strains of C. bescii expressing either extra- or intracellular form of the cellobiose phosphorylase, Tm_1848, from T. maritima. This gene was chosen because the enzyme was reported to be maximally active at 80°C (15). Expression of this cellobiose phosphorylase in C. bescii resulted in dramatic improvements in both the activity of the exoproteome and the ability of C. bescii to grow on Avicel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning and expression of a cellobiose phosphorylase from T. maritima MSB8 in C. bescii.

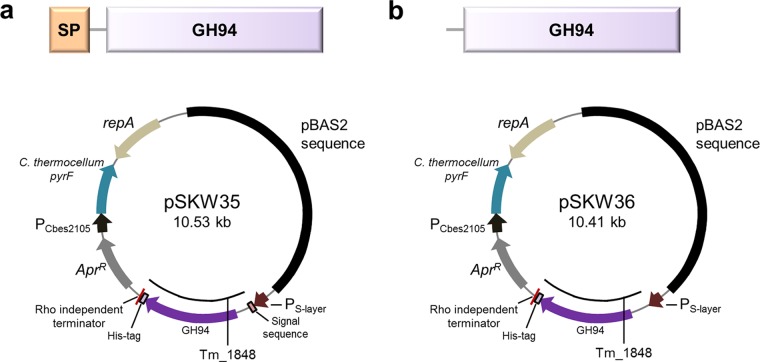

To construct a plasmid for intracellular or extracellular expression of Tm_1848 from T. maritima (Fig. 1) in C. bescii, the gene was amplified from T. maritima gDNA and cloned into shuttle vectors, pSKW35 and pSKW36 (Fig. 1), under the transcriptional control of the C. bescii S-layer promoter (16, 17). For extracellular expression the CelA signal sequence was added, resulting in pSKW35. CelA is the most abundant extracellular enzyme produced by C. bescii (1, 2), and we recently reported the use of this signal peptide for the secretion of proteins from A. cellulolyticus in C. bescii (6, 18). These plasmids were introduced into strain JWCB52, which contains the E1 protein from A. cellulolyticus inserted into the C. bescii chromosome (17). Strain JWCB52 also contains a deletion of pyrF, and transformants were selected for uracil prototrophy to generate JWCB107 (containing pSKW35) and JWCB108 (containing pSKW36). The resulting strains were grown at 65°C to accommodate the expression of Clostridium thermocellum pyrF gene used for complementation and plasmid selection. PCR analysis was used to confirm the presence and structure of the plasmids. Primers (DC460 and DC228) were used to amplify the portion of the plasmid containing the open reading frame of the targeted proteins (see Fig. S1a in the supplemental material). Total DNA from the JWCB107 and JWCB108 strains was used to back-transform E. coli, and two different restriction endonuclease digests performed on plasmid DNA purified from three independent back-transformants resulted in identical digestion patterns to the original plasmid (Fig. S1). These results indicated that the plasmids were successfully transformed into C. bescii and were structurally stable during transformation and replication in C. bescii and back-transformation into Escherichia coli.

FIG 1.

Construction of vectors for the expression of cellobiose phosphorylase from T. maritima (Tm_1848) in C. bescii. Schematic diagrams and maps of expression vectors for extracellular (a) and intracellular (b) expression of Tm_1848. Genes were expressed under the transcriptional control of the C. bescii S-layer promoter. The expression vectors contain a CelA signal sequence, a C-terminal 6×His tag, a Rho-independent terminator, the pyrF (from C. thermocellum) cassette for selection, and pBAS2 sequences for replication in C. bescii. SP, signal peptide; GH94, family 94 glycoside hydrolase.

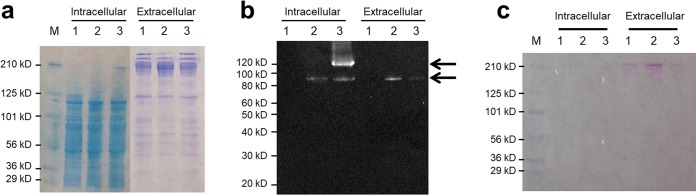

To investigate expression of Tm_1848 cellobiose phosphorylase in C. bescii, strains JWCB107 and JWCB108 (Table 1) were grown in low-osmolarity defined (LOD) medium with 40 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer containing 5 g/liter cellobiose (19). Although the Tm_1848 protein was difficult to identify using Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2a), it was clearly detected by Western hybridization analysis using monoclonal anti-His antibodies (Fig. 2b). As shown in Fig. 2b, no band corresponding to the 94-kDa predicted molecular mass of Tm_1848 was observed in either the intracellular or extracellular fraction obtained from the strain expressing E1 alone (lane 1). A band corresponding to Tm_1848 was clearly visible in both the intracellular and extracellular fractions of JWCB107 (with signal sequence) and JWCB108 (without signal sequence) strains (Fig. 2b). We suggest that intracellular accumulation of Tm_1848 with a signal sequence may be a consequence of limited secretion capacity of the C. bescii transport machinery for this protein (20). Comparison of the band intensities from the extracellular fractions showed that the band corresponding to the Tm_1848 protein in JWCB107 was 6.6 times greater than that in JWCB108. These results confirm expression of the protein without a signal sequence in the cytoplasmic fraction and enhanced extracellular expression of the protein with the CelA signal sequence.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid name | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JW543 | DH5α containing pSKW35 (apramycinR) | This study |

| JW544 | DH5α containing pSKW36 (apramycinR) | This study |

| C. bescii | ||

| JWCB52 | ΔpyrFA ldh::ISCbe4 Δcbe1::PS-layeracel0614(E1) (ura−/5-FOAR) | 6 |

| JWCB73 | JWCB52 containing pJGW07 (ura+/5-FOAS) | 18 |

| JWCB107 | JWCB52 containing pSKW35 (ura+/5-FOAS) | This study |

| JWCB108 | JWCB52 containing pSKW36 (ura+/5-FOAS) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJGW07 | E. coli/C. bescii shuttle vector containing the C. thermocellum pyrF gene (apramycinR) | 29 |

| pSKW12 | Intermediate vector (apramycinR) | 8 |

| pSKW35 | Expression vector for extracellular Tm_1848 (apramycinR) | This study |

| pSKW36 | Expression vector for intracellular Tm_1848 (apramycinR) | This study |

FIG 2.

Confirmation of cellobiose phosphorylase expression and glycosylation in C. bescii. Total cell lysates prepared from mid-log and stationary phases were electrophoresed either for (a) SDS-PAGE analysis with Coomassie blue staining or (b) for Western blot analysis probed with His tag antibody. (c) The same gel stained with Glycoprotein Stain (G-Biosciences). Lanes: M, prestained SDS-PAGE standards, broad range (Bio-Rad Laboratories); 1, JWCB73 (E1-expressing strain); 2, JWCB107 (E1- and extracellular-Tm_1848-expressing strain); 3, JWCB108 (E1 and intracellular-Tm_1848-expressing strain).

A protein band of approximate molecular mass 120 kDa was also detected in the intracellular fraction from the JWCB107 strain (Fig. 2b). One possible explanation for the presence of this band is that the Tm_1848 protein is glycosylated when expressed intracellularly in C. bescii. A similar result was reported by Fredriksen et al. (21), in which the major autolysin (Acm2) undergoes cytoplasmic glycosylation in the Gram-positive bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum. Intracellular protein glycosylation in C. bescii is unlikely, however. We recently showed that glycosylated CelA is detected only in the extracellular fraction. To investigate whether this 120-kDa band represented a glycosylated version of the Tm_1848 protein, we stained the gel with a G-Biosciences glycoprotein staining kit. The kit uses an enhanced periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) method for detection of glycoprotein sugars. An oxidizing agent first oxidizes the cis-diol sugar groups to aldehydes, and the aldehyde groups react with the Glyco-Stain Solution, forming Schiff bonds and producing a strong magenta color. As shown in Fig. 2c, there is no evidence that the Tm_1848 protein is glycosylated. Since the 120-kDa band is present only in the strain expressing the intracellular version of the Tm_1848 protein, we suggest that this band represents either a multimer of the Tm_1848 protein or a complex between the Tm_1848 protein and another intracellular protein. The maintenance of multimers of thermostable proteins in SDS-PAGE gels is not unprecedented. The β-d-glucosidase from Pyrococcus furiosus (BGLPf) appears to form a dimer that is stable in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate, and this dimer migrated in reducing SDS-PAGE even after incubation at 95°C (22). The nature of the protein or proteins present in this band is under investigation.

Intracellular expression of cellobiose phosphorylase from T. maritima MSB8 in C. bescii resulted in a significant increase in intracellular activity on cellobiose and a dramatic increase in growth on Avicel.

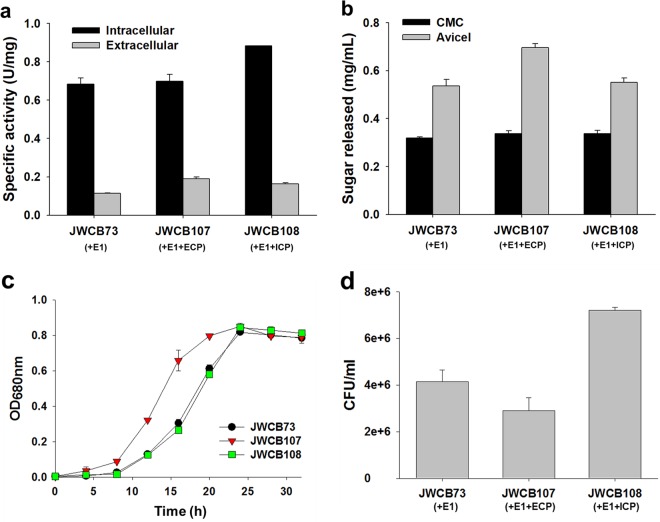

Cellobiose phosphorylase activity was measured in both the intracellular and extracellular fractions of strains expressing either the intracellular or extracellular forms of Tm_1848 and compared to the parent strain. Cells were grown at 65°C to accommodate expression of the C. thermocellum pyrF gene, and crude extracts were prepared from both the intracellular (cell extracts, CFE) and extracellular (extracellular protein, EP) fractions. CFE and EP fractions from strains expressing Tm_1848 as well as from the parent strain were assayed for cellobiose phosphorylase activity at 75°C, the optimal temperature for the exoproteome, on cellobiose as the substrate (Fig. 3a). While the optimal temperature for growth of A. cellulolyticus is 55°C (23), the optimal temperature for activity of Tm_1848 was reported to be 80°C (15). The activity of the extracellular fractions from all three strains was low. The exoproteome of JWCB107 (expressing the extracellular form of Tm_1848) showed the highest extracellular cellobiose phosphorylase activity of the three, 0.19 U/mg, 66% (P = 0.017) higher than that of the parental strain (JWCB73). Expression of the intracellular form of Tm_1848 in strain JWCB108 showed a 29% (P = 0.037) increase compared to that of the parental strain. C. bescii strains intracellularly hydrolyze cellobiose or cellodextrins after importing cellobiose with cellodextrin transporters (7). As expected, cellobiose phosphorylase activity was highest in the intracellular fraction. While extracellular expression of Tm_1848 showed the same activity as the parent strain, expression of the intracellular form of Tm_1848 resulted in a significant increase in intracellular activity.

FIG 3.

Effects of intracellular and extracellular expression of cellobiose phosphorylase (CP) on the activity of the C. bescii exoproteome and growth on cellobiose and Avicel. (a) The enzyme was incubated at 75°C for 10 min in reaction buffer containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and 10 mM cellobiose. Results are the means for triplicate experiments and error bars indicate standard deviations. (b) Activity of extracellular protein (25 μg/ml concentrated protein) on carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and Avicel. Results are the means for triplicate experiments and error bars indicate standard deviations. Growth of C. bescii strains on cellobiose (c) or Avicel (d). JWCB73, the E1 expression strain; JWCB107, the E1 expression strain containing Tm_1848 with signal sequence; JWCB108, the E1 expression strain containing Tm_1848 without signal sequence; ECP, extracellular cellobiose phosphorylase; ICP, intracellular cellobiose phosphorylase. Results are the means for duplicate experiments and error bars indicate standard deviations.

The exoproteomes isolated from the different strains were tested for their overall cellulase activity on both carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) for endoglucanase activity, and on Avicel for exoglucanase activity. From the results shown in Fig. 3, it is likely that the intracellular expression of Tm_1848 increases intracellular phosphorylation of cellobiose and therefore could promote better import of cellobiose. This better import might in turn reduce cellobiose accumulation in the growth medium and therefore lower inhibition of cellulases. A strain expressing the intracellular enzyme would be expected to grow better on Avicel, either because of increased phosphorylation of cellobiose, resulting in more rapid access to glucose, and/or because cellobiose import relieves the inhibition of exoglucanases. All C. bescii strains used in this study have the highest viable cell number after 24 h cultivation on Avicel. This is typical of C. bescii strains and the same as for strains previously reported (8, 24) (Fig. 3d). Growth of JWCB108, which expressed the intracellular form of the enzyme, on Avicel was 73% (P = 0.028) higher than that of the JWCB73 parent strain and 148% (P = 0.023) higher than that of JWCB107, which expressed the extracellular form of Tm_1848. Taken together, these data suggest that intracellular expression of Tm_1848 results in an increase in cellobiose hydrolysis and uptake by the cell. Furthermore, the resulting removal of cellobiose from the growth medium increases cellulase activity and growth on Avicel.

Extracellular expression of the cellobiose phosphorylase from T. maritima MSB8 in C. bescii resulted in a significant increase in activity of the exoproteome on Avicel and a dramatic reduction in the lag phase of growth on cellobiose.

To test the overall cellulase activity of strains expressing Tm_1848, glucose equivalents released (mg/ml) by the extracellular fraction from CMC or Avicel were measured. As shown in Fig. 3b, the CMC hydrolysis activity of exoproteomes from all three strains, JWCB73 (the parent strain), JWCB108 (the strain expressing the intracellular form of Tm_1848), and JWCB107 (the strain expressing the extracellular form of Tm_1848), was indistinguishable. Extracellular expression of Tm_1848, however, resulted in a dramatic increase in the activity of the exoproteome on Avicel compared to the parent strain or the strain expressing the intracellular form. The activity of the exoproteome of JWCB107 increased by 30% (P = 0.002) on Avicel at 75°C, indicating an increase in the exoglucanase activity of the exoproteome. The difference in the effect on CMC and Avicel digestion is most likely due to the fact that cellobiose is a stronger inhibitor of exoglucanases than endoglucanases, as shown by Teugjas and Valjamae (25), and mimics previous results (8). However, expression of the extracellular cellobiose phosphorylase also resulted in a reduction in growth on Avicel (Fig. 3d), most likely due to the conversion of cellobiose resulting from the hydrolysis of Avicel. Given that the transport of sugars in C. bescii is ATP dependent (7), transport of glucose results in a larger energetic burden. Interestingly, JWCB107 seemed to have improved initial growth compared to the parent strain or JWCB108 (Fig. 3c), suggesting that transport of cellobiose is a rate-limiting step for growth of C. bescii. The extracellular cellobiose phosphorylase produced by JWCB107 may catalyze the breakdown of some of the cellobiose into glucose and G1P, allowing an increase in intracellular concentration and/or transport of soluble sugars and cell growth. Utilization of cellobiose by C. bescii requires two steps: transport of cellobiose followed by phosphorolysis. On Avicel, cellobiose is slowly released in the medium, making intracellular activity rate-limiting. On cellobiose medium, cellobiose is in excess and therefore transport is a rate-limiting step. We speculate that this is the reason intracellular cellobiose phosphorylase expression did not improve growth on cellobiose.

Although the extracellular cellobiose phosphorylase activity of the JWCB107 strain was low, it was 66% (P = 0.017) higher than that of the parental strain and 29% (P = 0.037) higher than that of the strain expressing the intracellular form. This increase in the relatively low enzyme activity resulted in virtual elimination of the lag phase of growth on cellobiose compared to the parent strain or to the strain expressing an intracellular form (Fig. 3c). Growth of the parent strain and JWCB108, which expressed the intracellular version, was virtually identical, and all three strains reached the same final cell density. These data also show that expression of Tm_1848 in C. bescii had no obvious detrimental effect on growth in general. This suggests that expression of the cellobiose phosphorylase from T. maritima improved initial growth and that the ability of the enzyme to phosphorylate glucose provided a significant advantage. It also may indicate that this enzyme activity may be rate-limiting for growth and cellobiose phosphorolysis.

Conclusions.

Relieving cellobiose inhibition in cellulases and increasing sugar utilization for better biomass deconstruction and better growth in anaerobic bacteria is a fine balance between breaking down cellobiose and allowing faster import and utilization of sugars from biomass breakdown. This study is a perfect example of the delicate nature of this balance. Intracellular expression of a heterologous cellobiose phosphorylase led to increased growth but not to cellulolytic activity, as the microorganism can most likely import cellobiose more quickly and readily use it to enhance its metabolism. However, extracellular expression of the same heterologous cellobiose phosphorylase led to almost opposite results. The ability of the cellobiose phosphorylase to break down cellobiose to glucose and glucose 1-phosphate, which are less inhibitory to cellulases, logically led to an improvement in the cellulolytic activity of the exoproteome. However, this improvement came at the cost of lower growth, as the metabolic burden is greater for the microorganism when importing glucose rather than cellobiose. Nevertheless, this study clearly shows that with more control over intracellular and extracellular expression of this gene, one could envision creating a balanced C. bescii strain exhibiting both better biomass deconstruction and better sugar import and utilization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and culture conditions.

E. coli and C. bescii strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All C. bescii strains were grown in anaerobic conditions at 65°C on solid or in liquid low-osmolarity defined (LOD) medium (26) as previously described, with 5 g/liter maltose or cellobiose as sole carbon source for routine growth and transformation experiments (27). For growth of uracil auxotrophs, the defined medium contained 40 μM uracil. E. coli strain DH5α was used as a host for plasmid DNA construction and preparation using standard techniques. E. coli cells were cultured in LB broth containing apramycin (50 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a Qiagen Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Chromosomal DNA from C. bescii strains was extracted using the Quick-gDNA Miniprep kit (Zymo, Irving, CA) as previously described (28).

Construction and transformation of cellobiose phosphorylase expression vectors.

Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used for all PCRs, and restriction enzymes (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and the Fast-Link DNA ligase kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA) were used for plasmid construction according to the manufacturer's instructions. To construct plasmid pSKW35, a 2.4-kb DNA fragment containing the coding sequence of Tm_1848 was amplified using primers SK078 (with an XmaI site) and SK079 (with an SphI site), using T. maritima MSB8 gDNA as the template. In addition, a 8.1-kb DNA fragment containing a C. bescii replication origin from BAS2, an apramycin resistance gene cassette (AprR), a C. thermocellum pyrF expression cassette, the regulatory region of Cbes2303 (S-layer protein), the CelA signal sequence, a C-terminal 6×His tag, and a Rho-independent transcription terminator was amplified with primers SK021 (with an XmaI site) and SK055 (with an SphI site), using pSKW12 as the template. These two linear DNA fragments were digested with XmaI and SphI and ligated to construct pSKW35 (Fig. 1a). Plasmid pSKW36 is identical to pSKW35 except that it does not contain the CelA signal sequence for intracellular expression (Fig. 1). To make this change, a 10.4-kb DNA fragment without the CelA signal sequence was amplified with primers SK052 (with an ApaI site) and SK080 (with an ApaI site), using pSKW35 as the template. This linear DNA fragment was digested with ApaI and ligated to construct pSKW36 (Fig. 1b). These plasmids were introduced into E. coli DH5α cells by electroporation in a 1-mm-gap cuvette at 1.8 kV, and transformants were selected for apramycin resistance. All plasmids were sequenced by automatic sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ, USA). Electrotransformation of C. bescii cells was performed as previously described (29). After being electropulsed with plasmid DNA (∼0.5 μg), the cultures were recovered in low-osmolarity complex (LOC) medium (26) at 65°C. Recovery cultures were transferred to liquid LOD medium (26) without uracil to allow selection of uracil prototrophs. Cultures were plated on solid LOD media to obtain isolated colonies, and total DNA was extracted. Taq polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for PCRs to confirm the presence of the plasmid. PCR amplification was done with primers (DC460 and DC228) outside the gene cassette on the plasmid to confirm the presence of the plasmid with the Tm_1848 gene. Primers used for plasmid construction and confirmation are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Restriction enzyme | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| SK021 | CCGCCCGGGAAACGAACCAGCCCTAACCTCT | XmaI | To construct pSKW35 |

| SK055 | AGAGCATGCCATCACCATCACCATCACTAATAAT | SphI | |

| SK078 | CCGCCCGGGGTGCGATTCGGTTATTTTGATGACG | XmaI | To construct pSKW35 |

| SK079 | AGAGCATGCGCCCATCACAACTTCAACCCTG | SphI | |

| SK052 | TATAGGGCCCCTCACCAAACCTCCTTGTATGAT | ApaI | To construct pSKW36 |

| SK080 | TATAGGGCCCGTGCGATTCGGTTATTTTGATGACG | ApaI | |

| DC460 | AGAGAGCGATCGACAGTTTGATTACAGTTTAGTCAGAGCT | PvuI | To confirm transformants |

| DC228 | ATCATCCCCTTTTGCTGATG |

Italicized sequences indicate the recognition sites of the corresponding restriction enzymes.

Preparation of protein and Western blotting.

To collect cell extracts (CFE), C. bescii cells were grown in 500 ml of LOD medium with 40 mM MOPS in closed bottles at 65°C with shaking at 100 rpm to an optical density at 680 nm (OD680) of 0.25. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, suspended in CelLytic B cell lysis reagent (Sigma, USA), and lysed by a combination of 4× freeze-thawing and sonication (3× for 15 s at 40 A with 1-min rests on ice). Samples were centrifuged to separate protein lysate from cell debris, and the supernatant was used as CFE. To collect the extracellular protein (EP) fraction, C. bescii cells were grown in 2 liters of LOD medium with 40 mM MOPS in closed bottles at 65°C with shaking at 100 rpm to an OD680 of 0.25 to 0.3. Culture broth was centrifuged (6,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min) and filtered (glass fiber, 0.7 μm) to separate out cells. The 2 liters of EP were loaded into a hollow fiber cartridge with a 3-kDa molecular mass cutoff (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and eluted with 50 ml of buffer consisting of 20 mM MES and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (pH 5.5). Concentration of the 50 ml of EP was increased further (∼25 times) with a Vivaspin column (10-kDa molecular mass cutoff; Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. The CFE and EP were electrophoresed in 4 to 20% gradient Mini-Protean TGX gels, which were either stained using Coomassie blue or were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) using a Bio-Rad Mini-Protean 3 electrophoretic apparatus. The membrane was then probed with His tag (6×His) monoclonal antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) using the ECL Western blotting substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as specified by the manufacturer. The quantification of band intensity was carried out using the densitometry software (Total Lab 1.01; Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd.).

Enzyme activity assays.

The reaction of cellobiose phosphorylase was done at 75°C in an assay mixture consisting of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and 10 mM cellobiose. d-Glucose was measured by a glucose oxidase/peroxidase assay kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) as specified by the manufacturer. One unit of cellobiose phosphorylase activity was defined as the amount of cellobiose phosphorylase able to release 1 μmol d-glucose from cellobiose per minute. Specific enzyme activity (U/mg protein) was estimated by dividing the enzyme activity by the total protein concentration of the enzyme solution. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Cellulolytic activity was measured using 10 g/liter of either CMC or Avicel in MES [morpholineethanesulfonic acid or 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid] reaction buffer (pH 5.5) as previously described (30). Cells were grown in a 2-liter volume of LOD medium with 40 mM MOPS and cellobiose as carbon source. A total of 25 μg/ml of the extracellular protein fraction was added to each reaction and incubated at 75°C (1 h for CMC and 24 h for Avicel). Reducing sugars in the supernatant were measured using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method for reducing sugars (31). Samples and standards (glucose) were mixed 1:1 with DNS reaction solution, boiled for 2 min, and measured at an optical density of 575 nm (OD575.) Activity was reported as mg/ml of sugar released.

Growth of recombinant strains on cellobiose and Avicel.

To measure growth on cellobiose, cells were subcultured twice in LOD medium with 5 g/liter maltose as sole carbon source. This culture was used to inoculate media with 5 g/liter cellobiose (1% total volume for all experiments) as sole carbon source in 50 ml of LOD medium with 40 mM MOPS and incubated at 65°C with shaking at 150 rpm. Cell growth on cellobiose was measured at an optical density of 680 nm using a spectrophotometer. To measure growth on Avicel, cells were subcultured in LOD medium, first with 5 g/liter maltose and then with 5 g/liter Avicel. CFU were measured by plating cells on LOD medium (18).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shreena Patel for technical assistance and Joseph Groom and Jordan Russell for critical review of the manuscript as well as helpful discussions during the course of the work.

This work was supported by the BioEnergy Science Center (BESC) and Center for Bioenergy Innovation (CBI), U.S. DOE Bioenergy Research Centers, supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research in the DOE Office of Science. Oak Ridge National Laboratory is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the U.S. DOE under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02348-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang SJ, Kataeva I, Hamilton-Brehm SD, Engle NL, Tschaplinski TJ, Doeppke C, Davis M, Westpheling J, Adams MW. 2009. Efficient degradation of lignocellulosic plant biomass, without pretreatment, by the thermophilic anaerobe “Anaerocellum thermophilum” DSM 6725. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:4762–4769. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00236-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lochner A, Giannone RJ, Rodriguez M Jr, Shah MB, Mielenz JR, Keller M, Antranikian G, Graham DE, Hettich RL. 2011. Use of label-free quantitative proteomics to distinguish the secreted cellulolytic systems of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii and Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:4042–4054. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02811-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi Z, Su X, Revindran V, Mackie RI, Cann I. 2013. Molecular and biochemical analyses of CbCel9A/Cel48A, a highly secreted multi-modular cellulase by Caldicellulosiruptor bescii during growth on crystalline cellulose. PLoS One 8:e84172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunecky R, Alahuhta M, Xu Q, Donohoe BS, Crowley MF, Kataeva IA, Yang SJ, Resch MG, Adams MWW, Lunin VV, Himmel ME, Bomble YJ. 2013. Revealing nature's cellulase diversity: the digestion mechanism of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA. Science 342:1513–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1244273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. 2002. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung D, Young J, Cha M, Brunecky R, Bomble YJ, Himmel ME, Westpheling J. 2015. Expression of the Acidothermus cellulolyticus E1 endoglucanase in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii enhances its ability to deconstruct crystalline cellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:113. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dam P, Kataeva I, Yang SJ, Zhou FF, Yin YB, Chou WC, Poole FL, Westpheling J, Hettich R, Giannone R, Lewis DL, Kelly R, Gilbert HJ, Henrissat B, Xu Y, Adams MWW. 2011. Insights into plant biomass conversion from the genome of the anaerobic thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM. 6725. Nucleic Acids Res 39:3240–3254. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SK, Chung D, Himmel ME, Bomble YJ, Westpheling J. 2017. Heterologous expression of a β-d-glucosidase in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii has a surprisingly modest effect on the activity of the exoproteome and growth on crystalline cellulose. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 44:1643–1651. doi: 10.1007/s10295-017-1982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez PE, Ordonez JA, Sanz B. 1985. Utilization of cellobiose and d-glucose by Clostridium thermocellum ATCC-27405. Rev Esp Fisiol 41:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita Y, Takahashi S, Ueda M, Tanaka A, Okada H, Morikawa Y, Kawaguchi T, Arai M, Fukuda H, Kondo A. 2002. Direct and efficient production of ethanol from cellulosic material with a yeast strain displaying cellulolytic enzymes. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5136–5141. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5136-5141.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha SJ, Galazka JM, Oh EJ, Kordic V, Kim H, Jin YS, Cate JHD. 2013. Energetic benefits and rapid cellobiose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing cellobiose phosphorylase and mutant cellodextrin transporters. Metabol Eng 15:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang YHP, Lynd LR. 2004. Kinetics and relative importance of phosphorolytic and hydrolytic cleavage of cellodextrins and cellobiose in cell extracts of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1563–1569. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1563-1569.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang YHP, Lynd LR. 2005. Cellulose utilization by Clostridium thermocellum: bioenergetics and hydrolysis product assimilation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:7321–7325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408734102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lou J, Dawson KA, Strobel HJ. 1996. Role of phosphorolytic cleavage in cellobiose and cellodextrin metabolism by the ruminal bacterium Prevotella ruminicola. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1770–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajashekhara E, Kitaoka M, Kim YK, Hayashi K. 2002. Characterization of a cellobiose phosphorylase from a hyperthermophilic eubacterium, Thermotoga maritima MSB8. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 66:2578–2586. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung D, Cha M, Guss AM, Westpheling J. 2014. Direct conversion of plant biomass to ethanol by engineered Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:8931–8936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402210111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung D, Young J, Bomble YJ, Vander Wall TA, Groom J, Himmel ME, Westpheling J. 2015. Homologous expression of the Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA reveals that the extracellular protein is glycosylated. PLoS One 10:e0119508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SK, Chung D, Himmel ME, Bomble YJ, Westpheling J. 2016. Heterologous expression of family 10 xylanases from Acidothermus cellulolyticus enhances the exoproteome of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii and growth on xylan substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels 9:176. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0588-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung D, Cha M, Snyder EN, Elkins JG, Guss AM, Westpheling J. 2015. Cellulosic ethanol production via consolidated bioprocessing at 75°C by engineered Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:163. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg HF. 1998. Isolation of recombinant secretory proteins by limited induction and quantitative harvest. Biotechniques 24:188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredriksen L, Mathiesen G, Moen A, Bron PA, Kleerebezem M, Eijsink VGH, Egge-Jacobsen W. 2012. The major autolysin Acm2 from Lactobacillus plantarum undergoes cytoplasmic O-glycosylation. J Bacteriol 194:325–333. doi: 10.1128/JB.06314-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kado Y, Inoue T, Ishikawa K. 2011. Structure of hyperthermophilic β-glucosidase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 67:1473–1479. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111035238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohagheghi A, Grohmann K, Himmel M, Leighton L, Updegraff DM. 1986. Isolation and characterization of Acidothermus cellulolyticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus of thermophilic, acidophilic, cellulolytic bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 36:435–443. doi: 10.1099/00207713-36-3-435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SK, Chung D, Himmel ME, Bomble YJ, Westpheling J. 2016. Engineering the N-terminal end of CelA results in improved performance and growth of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii on crystalline cellulose. Biotechnol Bioeng 114:945–950. doi: 10.1002/bit.26242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teugjas H, Valjamae P. 2013. Product inhibition of cellulases studied with 14C-labeled cellulose substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:104. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farkas J, Chung D, Cha M, Copeland J, Grayeski P, Westpheling J. 2013. Improved growth media and culture techniques for genetic analysis and assessment of biomass utilization by Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 40:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung D, Farkas J, Westpheling J. 2013. Overcoming restriction as a barrier to DNA transformation in Caldicellulosiruptor species results in efficient marker replacement. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:82. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung D, Huddleston JR, Farkas J, Westpheling J. 2011. Identification and characterization of CbeI, a novel thermostable restriction enzyme from Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM 6725 and a member of a new subfamily of HaeIII-like enzymes. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 38:1867–1877. doi: 10.1007/s10295-011-0976-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groom J, Chung D, Young J, Westpheling J. 2014. Heterologous complementation of a pyrF deletion in Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis generates a new host for the analysis of biomass deconstruction. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:132. doi: 10.1186/s13068-014-0132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanafusa-Shinkai S, Wakayama J, Tsukamoto K, Hayashi N, Miyazaki Y, Ohmori H, Tajima K, Yokoyama H. 2013. Degradation of microcrystalline cellulose and non-pretreated plant biomass by a cell-free extracellular cellulase/hemicellulase system from the extreme thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. J Biosci Bioeng 115:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller GL. 1959. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.