Abstract

Purpose

The occurrence of thrombus migration (TM) in middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) prior to mechanical thrombectomy (MT) in patients suffering from acute ischemic strokes is a crucial aspect as TM is associated with lower rates of complete reperfusion and worse clinical outcomes. In this study, we sought to clarify whether histological thrombus composition influences TM.

Methods

We included 64 patients with acute MCA occlusions who had undergone MT. In 11 of the cases (17.2%) we identified TM prior to the interventions. The extracted clots were collected and histologically examined. The hematoxylin and eosin-stained specimens were quantitatively analyzed in terms of the relative fractions of the main constituents (red and white blood cells and fibrin/platelets). The histologic patterns were correlated with the occurrence of TM.

Results

Patients in whom TM could be observed were more often treated in a drip-and-ship fashion (90.9% vs 41.5%, p = 0.003). Stroke etiology did not differ between migrated and stable thrombi. A weak tendency for higher RBC and lower F/P content could be observed in thrombi that had migrated when compared with stable thrombi (RBC: median 41% vs 37%, p = 0.022 and F/P: median 54% vs 57%, p = 0.024). When using a cut-off of 60% RBC content for the definition of RBC-rich thrombi, a higher portion of RBC-rich thrombi could be identified in the migrated group as opposed to the stable group (36.4% vs 5.7%, p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Preinterventional TM may be influenced by the histological thrombus composition in a way that RBC-rich thrombi are more prone to migrate.

Keywords: Stroke, thrombus migration, blood cells, histology

Introduction

The overwhelming technical and clinical success of mechanical thrombectomy (MT) has led to its frequent use in endovascular procedures in specialized institutions. It could be shown that collection and histological work-up of thrombi is a valuable method to evaluate origin of clots and assess clinical outcome in patients.1–5

It has been shown before that the clots predominantly consist of three components: fibrin/platelet (F/P) accumulations, red blood cells (RBC), and white blood cells (WBC).3–7

The clot composition could be shown to be of prognostic importance and can additionally help to clarify the etiology of cryptogenic strokes and may therefore play an important role regarding issues of secondary stroke prevention.3,4

In the present study, we sought to address the phenomenon of thrombus migration (TM), which has previously been described as an important factor for the technical and clinical success of MT. TM occurring prior to endovascular therapies has been shown to be a common phenomenon with occurrence rates within the middle cerebral artery (MCA) ranging between 11% and 30% in the literature.8–11 TM is correlated with diminished technical success of subsequent endovascular procedures and possible worse clinical outcome.3,4,9 Nevertheless, there is no literature to date that addresses the rates of TM in vivo as a function of the clot composition. We thus questioned whether clot composition influences the rates of TM.

Material and methods

We retrospectively identified 75 patients with M1 occlusions of the MCA with preserved clots that were treated by endovascular thrombectomy using stent retrievers between October 2010 and September 2012. Seven patients were excluded because of insufficient follow-up imaging and four patients because of incomplete or missing preinterventional imaging. Thus, a total of 64 patients were suitable for our analysis. Approval of the local ethics committee was obtained prior to this study and it has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Procedure of MT

In all MT procedures used in this study, the so-called “Solumbra”-technique was performed.13–17 In brief, a distal access or aspiration catheter is navigated as close as possible to the clot. The clot is passed with a microwire and a microcatheter. After removing the microwire, a suitable stent retriever is deployed and after waiting for 3 minutes the stent retriever is carefully withdrawn into the distal access/aspiration catheter under intense aspiration. The gained thrombi were immediately fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin.

Processing and analysis of clot material

The technique of thrombus processing and histological analysis was described previously.3,4 In brief, the retrieved clot was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. The sample was thinly sliced and hematoxylin-eosin and Elastica van Gieson stainings were performed. The main clot components of F/P, RBC, and WBC were assessed and the relative quantitative fractions of the three thrombus components were evaluated using the software Adobe Photoshop CS4, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA.

Evaluation of TM

Our approach for analysis of TM was described previously.9 Image interpretation was performed by two experienced neuroradiologists. A consensus read was used in cases of disagreement. We discriminated direct evidence of TM, indirect evidence of TM, and lack of TM. In the case of direct evidence, the thrombus location revealed by the first digital subtraction angiography (DSA) run was undoubtedly localized more distally than in the preinterventional computed tomography angiography (CTA). If there was no clear direct evidence of TM, the infarct pattern regarding the lenticulostriate artery (LSA) territory was compared to the presented vessel occlusion. Consequently, indirect evidence of TM was assigned in cases of clear discrepancies between observed infarction in MRI three days after emergent large vessel occlusion (ELVO) and vessel occlusion presented in CTA/DSA (Figures 1 and 2).

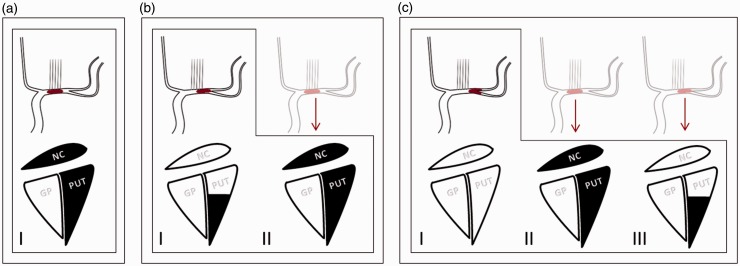

Figure 1.

Schematic explanation of indirect evidence of thrombus migration (TM) in the M1 segment of the MCA by means of different infarct patterns. Columns I in (a)–(c) represent the angiographic findings in DSA (upper panel) and the expected infarct patterns (lower panel) in follow-up imaging with respect to the occluded lenticulostriate arteries without TM. Columns II and III demonstrate infarct patterns that were found due to TM. The pale schematic angiographic illustrations show the probable thrombus positions prior to TM. Note that the Globus pallidus does not contribute to the presented scheme but may be involved in the infarct area. MCA: middle cerebral artery; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; NC: caudate nucleus (head); GP: globus pallidus; PUT: putamen.

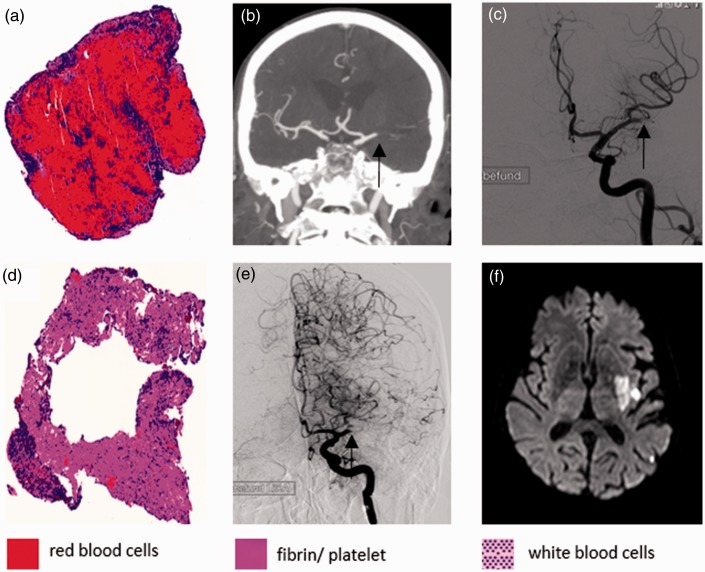

Figure 2.

Correlations of two segmented thrombi with different histological compositions and the respective radiological findings. The upper row demonstrates a red blood cell (RBC)-rich clot (a) that had caused an M1 occlusion as demonstrated by the CTA ((b) occlusion marked by an arrow). In first-run DSA the clot had migrated to the proximal M2 ((c) occlusion marked by an arrow). The lower row shows a non-RBC-rich clot (d) that had caused an MCA occlusion in the middle M1 segment without signs of migration. In CTA (not shown) and first-run DSA the proximal lenticulostriate arteries were uncovered by the thrombus and were apparent ((e) occlusion marked by an arrow). The occlusion site fits very well to the infarct pattern later seen on MRI three days after mechanical thrombectomy, sparing the caudate head and the rostral part of the putamen. Note a focal SAH in the sylvian fissure as an ancillary finding. CTA: computed tomography angiography; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; MCA: middle cerebral artery; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage.

A basic requirement for this approach is the relatively constant blood supply of the basal ganglia, especially of the caudate head and the putamen. Whereas the most anteromesial part of the caudate head is typically supplied by the recurrent artery of Heubner or other innominate anterior cerebral artery (ACA) perforators, the rest of the caudate head and the rostral tip of the putamen are typically supplied by mesial M1 LSAs.18,19 However, the anterior putamen, except for the rostral tip, is supplied by the middle M1 LSAs and the posterior putamen is supplied by the lateral LSAs of the MCA (Figure 1).

If there were neither direct nor indirect signs of TM, TM was rejected.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, release 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Interrater reliability was evaluated using Cohen’s κ. Frequency counts were compared using the Fisher exact test. Non-normally distributed data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and normally distributed data sets were compared using the t test for independent samples. To assess an independent association of different variables, a multivariate logistic regression model was used that included all significant variables from univariate comparison. In a second step, this model was further corrected for potential baseline confounders (age, sex and pretreatment with intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV rtPA)).

Results

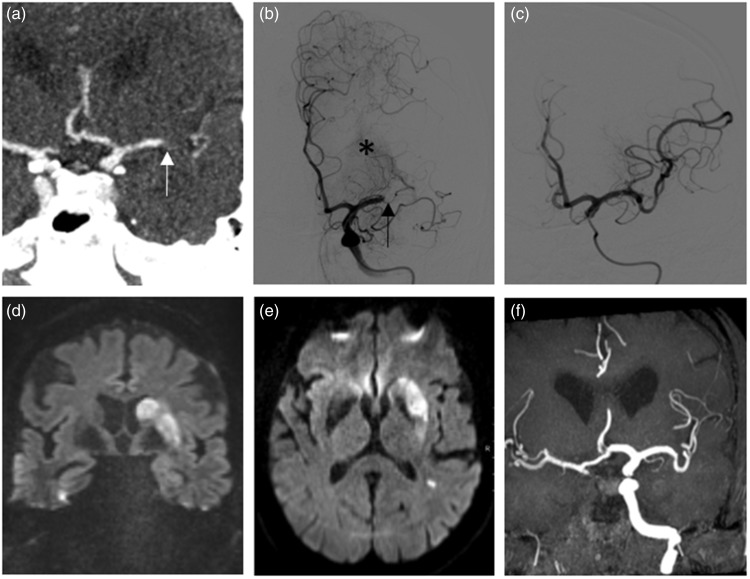

Of the 64 patients suffering from ELVO of the M1 segment of the MCA n = 11 (17.2%) patients were identified with either direct (n = 6; 9.4%, see Figure 2) or indirect (n = 5; 7.8%, see Figure 3) signs of TM prior to endovascular therapy. Interrater reliability was excellent (Cohen’s κ = 0.89) concerning the classification of TM.

Figure 3.

A 73-year-old female patient presenting with a distal M1 occlusion caused by an RBC-rich thrombus (not shown). In CTA (a), the occlusion site is marked by an arrow. First DSA run (b) demonstrates the occlusion in the same position as in the CTA. Lenticulostriate arteries (LSA, asterisk) are not blocked by the thrombus. (c) The angiographic situation after successful thrombectomy. Infarct pattern in MRI three days later ((d), (e)) demonstrates involvement of the basal ganglia as a clear indirect sign of thrombus migration as the thrombus had blocked the LSA before first presentation in CTA. (f) Time of flight angiography showing the same vascular situation as in last DSA run (c). RBC: red blood cell; CTA: computed tomography angiography; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Patients with proven TM had the same levels of RBC as patients without TM (median 41% vs 37%, p = 0.23). Regarding clots with high amounts of RBC (RBC-rich defined as RBC content >60%), TM was significantly more often observed in the RBC-rich group as compared to the non-RBC-rich group (57.1% vs 12.3%, p = 0.003), Table 1. Besides a higher proportion of patients treated in a drip ′n ship fashion, other baseline criteria analyzed showed no significant difference between the groups with and without TM (see Table 1). RBC-rich thrombi (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 18.214, 95% confidence interval, 95% CI 1.695–195.709) and drip ‘n ship treatment (aOR 22.299, 95% CI 1.817–273.638) were independently associated with TM in a multivariate logistic regression model. This association remained statistically tangible if this model was additionally corrected for potential confounders (age, sex and pretreatment with IV rtPA). The respective aORs were 17.152, 95% CI 1.439–204.478 and 25.829, 95% CI 2.026–329.255 for RBC-rich thrombi and drip ’n ship treatment, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and thrombus compositions.

| Thrombus migration (n = 11) | No thrombus migration (n = 53) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median, range | 75, 70–78 | 72, 59–80.5 | 0.27 |

| Female, n (%) | 5 (45.5) | 33 (62.3) | 0.30 |

| Drip ’n ship, n (%) | 10 (90.9) | 22 (41.5) | 0.003a |

| IV tPA, n (%) | 8 (72.7) | 36 (67.9) | 0.75 |

| Symptom onset to groin puncture, min (IQR) | 230 (217.5–240) | 170 (150.50–251.25) | 0.36 |

| Groin puncture to successful recanalization, min (IQR) | 40 (25–60) | 40 (20.5–65.57) | 0.71 |

| Stroke cause (TOAST), n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| 1 = arterioembolic | 1 (9.1) | 8 (15.1) | |

| 2 = cardioembolic | 7 (63.6) | 28 (52.8) | |

| 4 = other determined cause | 0 | 2 (3.8) | |

| 5 = cryptogenic | 3 (27.3) | 15 (28.3) | |

| Thrombus composition, %, median, range | |||

| F/P, %a | 54, 33–65 | 57, 49–69 | 0.24 |

| RBC, %a | 41, 29–60 | 37, 23–45.5 | 0.22 |

| WBC, %a | 5, 4–7 | 5, 4–7 | 0.96 |

| RBC-rich, n (%) | 4 (36.4) | 3 (5.7) | 0.003a |

IV rtPA: intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator; IQR: interquartile range; TOAST: Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment; F/P: fibrin/platelet; RBC: red blood cells; WBC: white blood cells; RBC-rich, clots with > 60% RBC.

p < 0.01.

Discussion

TM is known to be a common phenomenon in the MCA and can be detected using either direct or indirect criteria. TM is of general importance as it could be shown to independently predict lower rates of complete recanalization and even more important, decreased rates of neurologic improvement.9,20–22

To the best of our knowledge the present study is the first report addressing the question of TM in consideration of the different histological compositions of clots in patients with ELVO of the MCA. The basic finding of our study is that clots with high content of RBC (RBC-rich thrombi) are more prone to migration than non-RBC-rich clots. Our findings are consistent with a paper by Gunning et al.12 In this publication the frictions of clots of different fibrin to RBC ratios were tested on a surface ex vivo that was gradually tilted until the clots began to slide. The friction in non-RBC-rich clots was higher than in RBC-rich thrombi, which means that RBC-rich clots began to slide earlier on a consecutively more angulated surface.12 However, it is interesting that this effect persists under in vivo conditions in our study, as we expect many potential confounders that were not considered in the setting as reported by Gunning et al.12 such as vessel anatomy (including vessel bifurcations and tapering), hemodynamics, and endothelial factors including plaque formation.9

The reported effect might directly translate into clinical practice and influence clinical outcome in patients, as TM could be shown to be associated with higher ratios of incomplete recanalizations.9 As complete recanalizations are independently associated with higher rates of neurologic improvement after MT as compared to successful, but incomplete (thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) 2b) reperfusions, TM might be associated with worse clinical outcome.9,23

In a previously published paper, patients with a hyperdense artery sign at the occlusion site in preinterventional CT had a significantly higher probability of the clot being RBC-rich than patients without evidence of a hyperdense artery sign.24 This raises the question of whether special technical or procedural precautions should be taken into consideration while planning and performing MT in cases with suspected RBC-rich thrombi. Based on the assumption that RBC-rich clots are more fragile and therefore more prone to TM, the probability of achieving a TICI 3 result might be reduced in such cases with the aforementioned negative clinical repercussions.23 One possible approach to reduce the risk of TM during the procedure itself may be the additional use of proximal balloon catheters (proximal flow arrest) in conjunction with distal access catheters (distal aspiration) and stent retrievers.25 Another promising technical modification has been previously described to possibly successfully address the problem of peri-interventional TM. Here, semi-retrieval of the stent retriever during the thrombectomy procedure into the aspiration catheter is described, pinching the clot and subsequently removing it as a unit. This technique was associated with good first-pass TICI 3 results and few signs of TM and thrombus fragmentation.26–28

The current study has several limitations. First, it is an observational analysis. Procedural data were gained retrospectively. The principal methodological limitations were previously discussed.9 Furthermore, the study population is small and associations reached significance only in a dichotomized analysis. Owing to the small study cohort the range of the 95% CI was large. The number of documented direct signs of TM from CTA to first DSA was lower in cases of mothership patients (patients who were directly admitted to our Comprehensive Stroke Center) as compared to drip ’n ship patients, possibly because of a shorter interval from initial CTA to DSA. Nevertheless, this issue does not influence the core findings of our study as TM was still significantly more likely in RBC-rich clots among the subgroups of drip ’n ship patients (p = 0.044) as well as among mothership patients (p = 0.002).

Conclusion

TM may be influenced by the composition of the thrombus. We report first evidence that clots with high amounts of RBC inherit a higher risk for TM in vivo as compared to clots with lower amounts of RBC. This finding is clinically important as TM could be shown to have a negative impact on technical and clinical outcomes of patients suffering from emergent vessel occlusions of the MCA undergoing endovascular therapy.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Rebello LC, Bouslama M, Haussen DC, et al. Stroke etiology and collaterals: Atheroembolic strokes have greater collateral recruitment than cardioembolic strokes. Eur J Neurol 2017; 24: 762–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn SH, Hong R, Choo IS, et al. Histologic features of acute thrombi retrieved from stroke patients during mechanical reperfusion therapy. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 1036–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckh-Behrens T, Kleine JF, Zimmer C, et al. Thrombus histology suggests cardioembolic cause in cryptogenic stroke. Stroke 2016; 47: 1864–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeckh-Behrens T, Schubert M, Förschler A, et al. The impact of histological clot composition in embolic stroke. Clin Neuroradiol 2016; 26: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SK, Yoon W, Kim TS, et al. Histologic analysis of retrieved clots in acute ischemic stroke: Correlation with stroke etiology and gradient-echo MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 1756–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liebeskind DS, Sanossian N, Yong WH, et al. CT and MRI early vessel signs reflect clot composition in acute stroke. Stroke 2011; 42: 1237–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marder VJ, Chute DJ, Starkman S, et al. Analysis of thrombi retrieved from cerebral arteries of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2006; 37: 2086–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baik SH, Kwak HS, Hwang SB, et al. Manual aspiration thrombectomy using a Penumbra catheter in patients with acute migrated MCA occlusion. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaesmacher J, Maegerlein C, Kaesmacher M, et al. Thrombus migration in the middle cerebral artery: Incidence, imaging signs, and impact on success of endovascular thrombectomy. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6: e005149 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AI, Qureshi MH, Siddiq F, et al. Preprocedure change in arterial occlusion in acute ischemic stroke patients undergoing endovascular treatment by computed tomographic angiography. Am J Emerg Med 2015; 33: 631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janjua N, Alkawi A, Suri MF, et al. Impact of arterial reocclusion and distal fragmentation during thrombolysis among patients with acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunning GM, McArdle K, Mirza M, et al. Clot friction variation with fibrin content; implications for resistance to thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 2 January 2017. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012721. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lee JS, Hong JM, Lee SJ, et al. The combined use of mechanical thrombectomy devices is feasible for treating acute carotid terminus occlusion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013; 155: 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshaies EM. Tri-axial system using the Solitaire-FR and Penumbra Aspiration Microcatheter for acute mechanical thrombectomy. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20: 1303–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphries W, Hoit D, Doss VT, et al. Distal aspiration with retrievable stent assisted thrombectomy for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maegerlein C, Prothmann S, Lucia KE, et al. Intraprocedural thrombus fragmentation during interventional stroke treatment: A comparison of direct thrombus aspiration and stent retriever thrombectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017; 40: 987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prothmann S, Friedrich B, Boeckh-Behrens T, et al. Aspiration thrombectomy in clinical routine interventional stroke treatment: Is this the end of the stent retriever era? Clin Neuroradiol. Epub ahead of print 12 January 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s00062-016-0555-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kaplan HA, Krieger AJ. Vascular anatomy of the preoptic region of the brain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1980; 54: 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loukas M, Louis RG, Jr, Childs RS. Anatomical examination of the recurrent artery of Heubner. Clin Anat 2006; 19: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen TS, Lassen NA. A dynamic concept of middle cerebral artery occlusion and cerebral infarction in the acute state based on interpreting severe hyperemia as a sign of embolic migration. Stroke 1984; 15: 458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito I, Segawa H, Shiokawa Y, et al. Middle cerebral artery occlusion: Correlation of computed tomography and angiography with clinical outcome. Stroke 1987; 18: 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleine JF, Beller E, Zimmer C, et al. Lenticulostriate infarctions after successful mechanical thrombectomy in middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleine JF, Wunderlich S, Zimmer C, et al. Time to redefine success? TICI 3 versus TICI 2b recanalization in middle cerebral artery occlusion treated with thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brinjikji W, Duffy S, Burrows A, et al. Correlation of imaging and histopathology of thrombi in acute ischemic stroke with etiology and outcome: A systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 529–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stampfl S, Pfaff J, Herweh C, et al. Combined proximal balloon occlusion and distal aspiration: A new approach to prevent distal embolization during neurothrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei M, Wei Z, Li X, et al. Retrograde semi-retrieval technique for combined stentriever plus aspiration thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maus V, Behme D, Kabbasch C, et al. Maximizing first-pass complete reperfusion with SAVE. Clin Neuroradiol. Epub ahead of print 13 February 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s00062-017-0566-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.McTaggart RA, Tung EL, Yaghi S, et al. Continuous aspiration prior to intracranial vascular embolectomy (CAPTIVE): A technique which improves outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 16 December 2016. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012838. [DOI] [PubMed]