Abstract

Background

The association between body size and head and neck cancers (HNCA) is unclear, partly because of the biases in case-control studies.

Methods

In the prospective NIH-AARP cohort study, 218,854 participants (132,288 men and 86,566 women) aged 50–71, were cancer-free at baseline (1995 and 1996), and had valid anthropometric data. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the associations between body size and HNCA, adjusted for current and past smoking habits, alcohol intake, education, race and fruit and vegetable consumption, and reported as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Until 31 December 2006, 779 incident HNCA occurred: 342 in the oral cavity, 120 in the oro- and hypo-pharynx, 265 in the larynx, 12 in the nasopharynx, and 40 at overlapping sites. There was an inverse association between HNCA and body mass index, which was almost exclusively among current smokers (HR=0.76 per each 5 unit increase; 95%CI: 0.63–0.93), and diminished as initial years of follow-up were excluded. We observed a direct association with waist-to-hip ratio (HR=1.16 per 0.1 unit increase; 95%CI: 1.03–1.31), particularly for cancers of the oral cavity (HR=1.40; 95%CI: 1.17–1.67). Height was also directly associated with total head and neck cancers (p=0.02), and oro-and hypopharyngeal cancers (p<0.01).

Conclusions

The risk of head and neck cancers was associated inversely with leanness among current smokers, and directly with abdominal obesity and height.

Impact

Our study provides evidence that the association between leanness and risk of head and neck cancers may be due to effect modification by smoking.

Introduction

Each year between 550,000 and 650,000 new cases of cancers of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and nasopharynx, collectively known as head and neck cancers (HNCA), are diagnosed in the world (1, 2). These cancers share many characteristics: more than 90% of them are squamous cell carcinomas and have similar risk factors(3), they are more much common in men and among people from South-Central Asia, and Central and Eastern Europe (4)). In the US, in 2013, more than 53,000 new cases of HNCA’s were reported, comprising about 3% of all cancers, and about 11,000 people died due to them which constitute about 2% of all cancer deaths (5). The trends in the incidence rates of these cancers have been different according to etiology, geographical location, and age groups. In general, developed countries, including the US, have seen an increase in oropharyngeal cancers, which are linked to human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, particularly in younger birth cohorts (6). This is while the smoking-related cancers of the oral cavity have been declining in men, and increasing or stable among women in these countries (6).

While smoking, alcohol (7, 8) and HPV (9) are known risk factors for head and neck cancers, there has been some controversy about the role of obesity and leanness. Some studies have shown that these cancers, unlike many others (10), are associated with leanness, and overweight and obesity have inverse associations with their risk(11–13). All of these studies have been case-control studies, which are particularly prone to recall bias or reverse causation. Two prospective studies, before the current report, have studied the relationship between body size and HNCA: the Cancer Prevention Study 2 (CPS-II) (14), and The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) study (15). Neither showed any association between BMI and the incidence of head and neck cancers, but CPS-II showed an inverse relationship with mortality from these cancers (14).

Both of the previous prospective studies had fewer incident cases than the case-control studies which did show an inverse association. Moreover they were underpowered to examine sub-sites of HNCA. For these reasons, we decided to study the association between different anthropometric measures and HNCA using the data from a larger cohort; the National Institutes of Health–AARP (NIH–AARP) Diet and Health Study.

Materials and Methods

Details of the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study have been published previously (16). A baseline questionnaire was mailed between 1995 and 1996 to 3.5 million AARP members (50–71 years old) from six US states (California, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina and Pennsylvania) and two metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Georgia and Detroit, Michigan); 566,401 respondents completed the survey, consented to participate in the study, and provided information on weight and height. Six months later, 334,907 respondents completed and returned a follow-up risk factor questionnaire, including information on waist and hip measurements; participants recorded waist and hip measurements, to the nearest 0.25 inch, according to detailed instructions. We excluded subjects with a cancer diagnosis before returning the risk factor questionnaire (4552), proxy respondents (10,383), those missing data for body mass index (BMI) (6608), or waist or hip measurements (88,255). Subjects who reported extreme (more than two times the interquartile range (IQR) of sex-specific log-transformed values) total energy intake (1672), BMI (2191), waist (578) and hip (1813) measurements were also excluded. Those subjects who died or were diagnosed with cancer on the first day of follow-up were excluded (one). The resulting cohort included 218,854 participants: 132,288 men and 86,566 women.

Cohort follow-up

Follow-up time extended from the day of study entry to the earliest of the following: date of death, date of diagnosis of head and neck or first upper gastrointestinal cancer (as a diagnosis of one of these cancers would be associated with increased surveillance of HNCA), participant relocation out of the registry ascertainment area, or 31 December 2006. Vital status was ascertained by linkage to the Social Security Administration Death Master File in the USA, follow-up searches of the National Death Index, cancer registries, questionnaire responses and responses to other mailings. Addresses for members of the cohort were updated annually through the USA Postal Service database and also linkage to commercial address databases. This method proved to be very robust as during 9 years of follow-up in a pilot study, only 2.5% (288/11,404) of surviving pilot study participants moved out of the cohort regions.

Identification of cancer cases

We used probabilistic linkage between the NIH-AARP cohort membership and state cancer registry databases to identify the incident cancer cases, a method which has been estimated to detect 90% of cancer cases in the cohort. Cancer sites were identified by anatomic site and histologic code of the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, third edition. All cases of head and neck cancer with squamous histology were considered for this analysis (C32.0–C32.9, C00.1–C06.9, C09.0–C09.9, C10.0–C10.9, C12.9, C13.0–C13.9, and C14.0). The overarching head and neck cancer category included those diagnosed with a cancer of the oral cavity, oropharynx and hypopharynx, larynx, nasopharynx, and those with other squamous tumors in the head or neck or overlapping region of the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx.

Statistical analysis

We used multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The first two years of follow-up were excluded to reduce the potential effect of subclinical cancer or reverse causation. We fitted a model for the incidence of any head and neck cancer as the outcome, and then fitted separate models for each subsite (oral cavity, oro-pharynx, and larynx). We did not perform a separate analysis for nasopharyngeal cancers, because there were too few cases for the models to converge (n=12). Sex-specific quartiles were used for height, weight, waist circumference, hip circumference and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR). For BMI, we used predefined World Health Organization (WHO) standard categories: underweight, less than 18.5 kg/m2; normal, 18.5 to less than 25; overweight, 25 to less than 30; obese, 30 or greater.

The fully adjusted models also included age and sex, marital status (yes/no), ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American), cigarette smoking (never smokers, former smokers who smoked ≤20 cigarettes/day, former smokers who smoked >20 cigarettes/day, current smokers who smoke ≤20 cigarettes/day and current smokers who smoke >20 cigarettes/day), education (high school graduate or less, post high school training or some college training, college graduate and postgraduate education), vigorous physical activity (never, rarely, 1–3 times/month, 1–2 times/week, 3–4 times/week, 5 or more times per week), usual activity throughout the day (sit all day, sit much of the day/walk some times, stand/walk often/no lifting, lift/carry light loads and carry heavy loads), alcohol consumption (none, >0–0.5, >0.5–1, >1–2, >2–4, >4 drinks per day), fruit and vegetable intakes (both pyramid servings per day). Red and white meat intake, total energy intake, antacid, aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and diabetes were originally included in the models, but were later dropped because they changed the risk estimates for anthropometric indices less than 1%. Models for abdominal obesity (hip, waist and waist-to-hip ratio) were also adjusted for BMI, and those for height were adjusted for weight.

Tests for trend across the categories of anthropometric variables were evaluated by assigning each participant the median category value and modeling this value as a continuous variable. We used restricted cubic spline models to generate plots of the relationship between continuous variables and risk of head and neck cancers. These models allow for studying non-linear relationships between an exposure and an outcome. We also evaluated effect modification by smoking (ever/former/never) by performing stratified analysis and evaluating interaction terms. All analyses were carried out using SAS V.9.1 and we used two-sided tests, interpreting p<0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

During the follow-up, a total of 779 cases of head and neck cancers accrued to the cohort. The most common site was the oral cavity, and the least common was nasopharynx (Table 1). Of these cases, 149 occurred during the first 2 years of follow up, which was during the period excluded from the multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics across categories of body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) quartiles among participants in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study

| Characteristic | BMI categories 1 | WHR quartiles 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal | Overweight | Obese | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

| Number (%) | 1,854 (0.8) | 86,672 (39.6) | 92,758 (42.4) | 37,5670 (17.2) | 54,773 (25.0) | 54,776 (25.0) | 54,658 (25.0) | 54,642 (25.0) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.4 (5.3) | 63.1 (5.3) | 63.1 (5.2) | 62.9 (5.2) | 62.4 (5.2) | 63.0 (5.2) | 63.3 (5.2) | 63.3 (5.2) |

| Height (m), mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Married, Yes, % | 48.2 | 66.1 | 76.2 | 70.4 | 71.5 | 71.7 | 71.2 | 69.3 |

| Total fruit (servings/day), mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.2 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.3) | 2.8 (2.3) |

| Total vegetables (servings/day), mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.5) | 3.9 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.5) | 3.9 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.3) | 3.9 (2.3) |

| Alcohol (drinks/day), mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.8 (2.0) | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.8 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.8) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white, % | 95.0 | 94.8 | 94.6 | 93.7 | 93.5 | 94.6 | 94.8 | 95.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black, % | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| Hispanic, % | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Other, % | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Education | ||||||||

| High school or less, % | 21.2 | 19.7 | 21.5 | 25.0 | 18.5 | 19.9 | 22.2 | 24.9 |

| Post high school, % | 9.4 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 11.3 |

| Some college, % | 24.7 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 25.9 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 23.8 | 24.6 |

| College and post graduate, % | 44.8 | 47.6 | 44.6 | 38.0 | 48.8 | 46.9 | 43.7 | 39.2 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never smoked, % | 38.9 | 40.8 | 35.1 | 35.5 | 41.9 | 39.0 | 36.7 | 32.3 |

| Former ≤ 20 cigarettes/day, % | 22.3 | 28.7 | 29.5 | 26.3 | 29.2 | 29.4 | 28.8 | 27.0 |

| Former > 20 cigarettes/day, % | 11.3 | 15.6 | 24.9 | 29.0 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 22.6 | 26.8 |

| Current ≤ 20 cigarettes/day, % | 19.6 | 10.0 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 8.1 |

| Current > 20 cigarettes/day, % | 7.9 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.8 |

| Vigorous physical activity | ||||||||

| Never, % | 6.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| Rarely, % | 15.0 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 16.9 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 11.8 | 15.2 |

| 1–3 time/month, % | 11.5 | 10.9 | 12.9 | 16.8 | 10.9 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 14.9 |

| 1–2 times/week, % | 17.9 | 20.0 | 22.9 | 23.6 | 20.3 | 21.9 | 22.4 | 22.8 |

| 3–4 times/week, % | 25.2 | 30.9 | 30.0 | 23.8 | 31.6 | 30.5 | 29.1 | 25.7 |

| ≥5 times/week, % | 24.4 | 25.8 | 20.8 | 14.2 | 26.4 | 23.3 | 20.2 | 16.8 |

| Cancer sites | ||||||||

| Total head and neck cancers2, N (%) | 10 (1.3) | 316 (40.6) | 323 (41.5) | 130 (16.6) | 181 (23.2) | 180 (23.1) | 204 (26.2) | 214 (27.5) |

| Oral Cavity Cancer, N (%) | 3 (0.8) | 147 (43.0) | 137 (40.1) | 55 (16.1) | 72 (21.1) | 75 (21.9) | 91 (26.6) | 104 (30.4) |

| Oro- and hypopharynx cancer, N (%) | 4 (3.3) | 47 (39.2) | 55 (45.8) | 14 (11.7) | 35 (29.2) | 22 (18.3) | 32 (26.7) | 31 (25.8) |

| Laryngeal cancer, N (%) | 3 (1.1) | 100 (37.9) | 112 (42.4) | 49 (18.6) | 58 (22.0) | 70 (26.5) | 67 (25.4) | 69 (26.1) |

| Nasopharynx cancer, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (41.7) | 5 (41.7) | 2 (16.6) | 2 (16.6) | 3 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (33.4) |

SD: standard deviation

Predefined categories according to the WHO standard definitions: underweight <18.5 kg/m2, normal 18.5–<25, overweight 25–<30, obese ≥30.

the total number of head and neck cancers is greater than the four subsites (oral cavity cancer, oro- and hypopharynx cancer, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, nasopharynx cancer) because subjects diagnosed with tumors that overlapped more than one of these sites were omitted from the individual subsites.

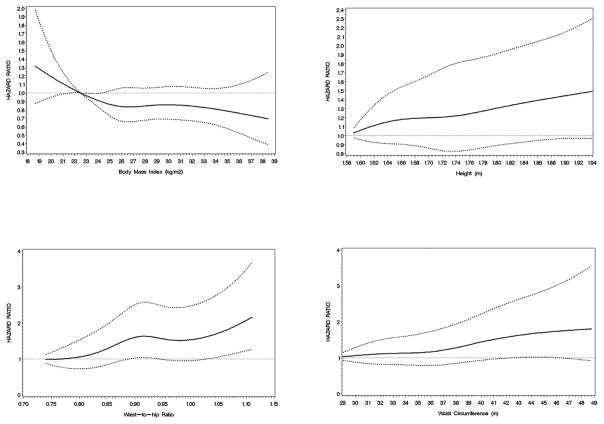

We observed inverse associations between baseline BMI and total head and neck cancers, although none of these were statistically significant (Table 2). When stratified by smoking (Table 3), the inverse association was only observed among current (and not former) smokers (HR=0.76 per 5 unit increase; 95% CI: 0.63–0.93). Also, when we used different latency periods, the associations between BMI and head and neck cancers diminished as we excluded more initial years of follow-up, while a similar effect was not seen among cancer cases diagnosed soon after baseline (Table 4). BMI at earlier ages showed no association with total head and neck cancers (Supplementary Table). As table 2 shows, unlike BMI, waist circumference was associated with an increased risk of total head and neck cancers and those in the highest quartile of waist had a 1.42 times higher risk (95% CI: 1.04–1.93). This association was also strongest among current smokers (Table 3), but did not diminish when early follow-up was excluded (Table 4). Risk of total head and neck cancers was also increased among individuals in the fourth quartile of height (HR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.06–1.69), and there was a significant increasing trend for the association between height and total head and neck cancer risk (Table 2). Figure 1 summarizes the associations between anthropometric measurements and total head and neck cancer risk.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of head and neck cancers across categories of anthropometric measures in the NIH-AARP Diet and health Study1

| Characteristic2 | Median by quartile/category (men/women) | Total head and neck cancers | Oral cavity cancer | Oro- and hypopharynx cancer | Laryngeal cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cases (n) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95%CI) | Cases (n) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95%CI) | Cases (n) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95%CI) | Cases (n) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95%CI) | ||

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| <18.5 | 18.0/17.9 | 8 | 1.70 (0.84–3.46) | 2 | 0.88 (0.22–3.57) | 3 | 4.20 (1.28–13.81) | 3 | 2.18 (0.68–6.98) |

| 18.5–<25 | 23.5/22.5 | 249 | 1.00 (Ref) | 112 | 1.00 (Ref) | 39 | 1.00 (Ref) | 79 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 25–<30 | 27.0/27.0 | 272 | 0.88 (0.73–1.04) | 120 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 47 | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | 90 | 0.89 (0.65–1.21) |

| ≥ 30 | 31.6/31.9 | 101 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 39 | 0.76 (0.52–1.11) | 12 | 0.61 (0.31–1.18) | 39 | 1.04 (0.70–1.55) |

| P for trend3 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.79 | |||||

| Height (m) | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.70/1.57 | 150 | 1.00 (Ref) | 68 | 1.00 (Ref) | 20 | 1.00 (Ref) | 52 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2 | 1.78/1.63 | 176 | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) | 80 | 1.06 (0.76–1.45) | 22 | 1.07 (0.58–1.98) | 61 | 1.06 (0.72–1.54) |

| 3 | 1.80/1.65 | 103 | 1.14 (0.88–1.48) | 37 | 0.85 (0.56–1.28) | 20 | 1.91 (1.00–3.63) | 40 | 1.29 (0.84–1.98) |

| 4 | 1.85/1.73 | 201 | 1.34 (1.06–1.69) | 88 | 1.31 (0.92–1.86) | 39 | 2.28 (1.26–4.15) | 58 | 1.04 (0.68–1.57) |

| P for trend | 0.02 | 0.19 | <0.01 | 0.75 | |||||

| Waist circumference (in) | |||||||||

| 1 | 34.0/27.8 | 153 | 1.00 (Ref) | 56 | 1.00 (Ref) | 28 | 1.00 (Ref) | 58 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2 | 36.5/31.0 | 125 | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) | 50 | 1.14 (0.77–1.69) | 22 | 1.05 (0.59–1.87) | 41 | 0.81 (0.53–1.22) |

| 3 | 39.0/34.0 | 193 | 1.25 (0.98–1.59) | 101 | 2.01 (1.39–2.91) | 26 | 0.04 (0.56–1.90) | 55 | 0.80 (0.53–1.22) |

| 4 | 43.5/39.0 | 159 | 1.42 (1.04–1.93) | 66 | 2.00 (1.24–3.23) | 25 | 1.53 (0.72–3.25) | 57 | 0.98 (0.58–1.66) |

| P for trend | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.99 | |||||

| Hip circumference (in) | |||||||||

| 1 | 37.0/36.0 | 193 | 1.00 (Ref) | 76 | 1.00 (Ref) | 36 | 1.00 (Ref) | 66 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2 | 39.5/39.0 | 147 | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 73 | 1.06 (0.76–1.48) | 20 | 0.67 (0.38–1.18) | 45 | 0.78 (0.53–1.15) |

| 3 | 41.3/42.0 | 131 | 0.88 (0.69–1.12) | 57 | 0.96 (0.66–1.40) | 23 | 0.93 (0.52–1.66) | 44 | 0.83 (0.55–1.26) |

| 4 | 44.0/46.0 | 159 | 1.06 (0.80–1.39) | 67 | 1.17 (0.76–1.80) | 22 | 0.98 (0.49–1.96) | 56 | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) |

| P for trend | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.54 | |||||

| WHR | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.88/0.73 | 141 | 1.00 (Ref) | 53 | 1.00 (Ref) | 29 | 1.00 (Ref) | 47 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2 | 0.93/0.78 | 142 | 0.97 (0.77–1.23) | 57 | 1.06 (0.73–1.55) | 19 | 0.63 (0.35–1.13) | 55 | 1.10 (0.75–1.63) |

| 3 | 0.96/0.83 | 169 | 1.12 (0.89–1.41) | 78 | 1.45 (1.01–2.07) | 28 | 0.89 (0.52–1.51) | 50 | 0.95 (0.63–1.42) |

| 4 | 1.02/0.90 | 178 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) | 85 | 1.58 (1.10–2.28) | 25 | 0.77 (0.43–1.37) | 59 | 1.01 (0.67–1.52) |

| P for trend | 0.15 | <0.01 | 0.54 | 0.90 | |||||

BMI = body mass index; WHR = waist-to-hip ratio.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Risk estimates adjusted for age, sex, marital status, cigarette smoking, education, ethnicity, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable intake; also height adjusted for weight and waist, hip and WHR adjusted for BMI.

Anthropometric characteristic categories represent sex-specific quartiles for men and women combined.

P value for trend across categories is based on the median category values being assigned to each subject within categories and modeled as a continuous variable.

Table 3.

Trends of hazard ratios of head and neck cancers for increasing waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index (BMI) at different ages in the NIH-AARP Diet and health Study1

| Total head and neck cancers | Oral cavity cancer | Oro- and hypopharynx cancer | Laryngeal cancer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Per 5 unit increase in baseline BMI (kg/m2) | All | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 0.87 (0.74–1.03) | 0.71 (0.53–0.95) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) |

| Never-smokers | 0.98 (0.76–1.26) | 0.95 (0.69–1.32) | 0.63 (0.29–1.36) | 1.54 (0.86–2.75) | |

| Former smokers | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | 0.91 (0.72–1.16) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 1.02 (0.78–1.35) | |

| Current smokers | 0.76 (0.63–0.93) | 0.70 (0.50–0.98) | 0.44 (0.26–0.76) | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | |

| Interaction p value | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.16 | |

| Per 0.1 unit increase in waist-to-hip ratio | All | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 1.40 (1.17–1.67) | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 1.10 (0.89–1.35) |

| Never-smokers | 1.08 (0.79–1.47) | 1.31 (0.89–1.92) | 0.38 (0.16–0.94) | 0.90 (0.42–1.93) | |

| Former smokers | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 1.57 (1.22–2.01) | 0.58 (0.36–0.91) | 1.09 (0.80–1.51) | |

| Current smokers | 1.25 (1.02–1.54) | 1.25 (0.89–1.75) | 1.96 (1.22–3.16) | 1.16 (0.84–1.59) | |

| Interaction p value | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.27 | |

BMI = body mass index; WHR = waist-to-hip ratio.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Risk estimates adjusted for age, sex, marital status, cigarette smoking, education, ethnicity, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable intake.

Table 4.

Trends of hazard ratios of head and neck cancers for increasing waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index (BMI) using different latency analyses during follow up in the NIH-AARP Diet and health Study1

| Type of latency analysis | Total head and neck cancers | Oral cavity cancer | Oro- and hypopharynx cancer | Laryngeal cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per 5 unit increase in baseline BMI (kg/m2) | Including only the first 2 years | 0.89 (0.81–0.99) | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.72 (0.55–0.93) | 0.99 (0.84–1.16) |

| Excluding the first 2 years | 0.89 (0.78–0.99) | 0.87 (0.74–1.03) | 0.71 (0.53–0.95) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | |

| Including only the first 4 years | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 0.99 (0.84–1.16) | |

| Excluding the first 4 years | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 0.71 (0.51–0.99) | 1.03 (0.83–1.27) | |

| Including only the first 6 years | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 0.98 (0.84–1.16) | |

| Excluding the first 6 years | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.86 (0.59–1.26) | 0.92 (0.70–1.20) | |

| Per 0.1 unit increase in baseline WHR | Including only the first 2 years | 1.10 (0.99–1.23) | 1.31 (1.12–1.54) | 0.86 (0.645–1.16) | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) |

| Excluding the first 2 years | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 1.40 (1.17–1.67) | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 1.10 (0.89–1.35) | |

| Including only the first 4 years | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 1.32 (1.12–1.55) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | |

| Excluding the first 4 years | 1.18 (1.02–1.35) | 1.40 (1.15–1.72) | 0.88 (0.61–1.28) | 1.13 (0.89–1.44) | |

| Including only the first 6 years | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 1.32 (1.12–1.55) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 1.06 (0.88–1.29) | |

| Excluding the first 6 years | 1.22 (1.03–1.44) | 1.41 (1.10–1.81) | 0.97 (0.63–1.49) | 1.28 (0.95–1.72) |

BMI = body mass index; WHR = waist-to-hip ratio.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Risk estimates adjusted for age, sex, marital status, cigarette smoking, education, ethnicity, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable intake.

Figure 1.

Spline plots of the relationship between anthropometric measurements at baseline and total head and neck cancer risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and health Study. The figures plot, clockwise, body mass index, height, waist-to hip ratio, and waist circumference. The solid line represents the estimate of the hazard ratio while the broken lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Among the subtypes, cancers of the oral cavity showed a pattern similar to what we observed for total head and neck cancers (Tables 2 and 3): while there was an inverse association with BMI particularly among current smokers (HR=0.70 per 5 unit increase in BMI; 95%CI: 0.50–0.98), those in the two highest quartiles of waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio had a higher risk of these cancers (Table 2). The inverse association with BMI diminished with more early years of follow-up excluded, while the association with WHR persisted (Table 4). The association between oral cavity cancers and height was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Oro- and hypopharyngeal cancers had a similar inverse association with BMI in total, which was particularly strong among current smokers (HR=0.44 per 5 unit increase; 95%CI: 0.26–0.76), and the direct association with WHR was only seen among this group (HR=1.96 per 0.1 unit increase; 95%CI: 1.22–3.16) (Table 3). This was the only subtype which showed an increased risk among tall individuals (highest vs. lowest quartile HR= 2.28; 95% CI: 1.26–4.15), with a significant trend (p<0.01; Table 2).

As tables 2–4 show, laryngeal cancers seemed to be independent of any of the studied anthropometric measures.

Discussion

Our results showed evidence for an inverse relationship between BMI at cohort baseline and head and neck cancers in general, and cancers of the oral cavity and oro- and hypo-pharynx in particular, which was almost exclusively present among current smokers. This is while we observed a direct association with abdominal obesity, particularly for cancers of the oral cavity. The association with BMI diminished as more earlier years of follow up were excluded, but the association with abdominal obesity remained stable. Height was also directly associated with total head and neck cancers, and oro-and hypopharyngeal cancers. Among the subsites, laryngeal cancers were not associated with any of the anthropometric measures studied.

Case-control studies seem to suggest that leanness is associated with increased odds of head and neck cancers (11–13, 17, 18), though one of these studies showed such an association only among African-Americans (13). Investigators have suggested three possible reasons for this apparent association: first, confounding by smoking or another risk factor, second reverse causation, and third a real protective effect of overweight or obesity (12). These case-control studies cannot distinguish reverse causation from a truly increased risk and may be prone to recall bias for many important confounders. Two previous prospective studies have also studied this association. The CPS-II (14) did not show any association between BMI and the incidence of head and neck cancers, but demonstrated an inverse relationship with mortality from these cancers. This inverse relationship was only observed among smokers, which might be because of the effect modification by smoking or due to chance. Results from the PLCO cohort (15) did not show an association between BMI and incident head and neck cancers. Our study had more cases of HNCA than both of these studies combined, and shows that current smokers are the only group with some evidence for an inverse association, and that the association diminishes as more initial years of follow-up are excluded from the study. The differential effect of body weight among smokers has been observed in the case-control studies too (13, 17, 18).

Smoking, along with alcohol use, has been shown to be strongly associated with HNCAs(2, 7). The carcinogenicity of many compounds in tobacco (such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs) depends on the formation of DNA adducts, and is the result of a trade-off between DNA damage and repair (19). The molecular mechanisms involved in smoking-related malignancies may be influenced by body weight. For example, leanness may increase smoking-induced oxidative DNA damage (measured by urinary 8-OHdG level) and thus affect the host susceptibility to cancer (20). Therefore, the association between leanness and smoking-related cancers such as HNCA, lung cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma might be due to real biologic differences (10, 21).

It has also been shown that smoking has different effects on general and abdominal obesity. Many investigators have reported that while smokers have lower BMI, they tend to have increased waist circumference and WHR (22–24). This has been attributed to a loss of muscle mass in smokers, which may be due to altered dietary habits and hormonal changes due to smoking (23), or a direct nicotine effect (22). Many of these effects are attenuated after quitting smoking (22, 23). This can explain why, in our study, the measures of abdominal obesity (waist circumference and WHR) showed a pattern of association from BMI, and were directly associated with the risk of HNCA, and why former and never smokers appeared to have more similar associations with these measures. The relationship between abdominal obesity and cancer may be mediated through insulin resistance, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) secretion and/or growth hormone resistance in the liver. Both IGF-1 and insulin promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis(25).

Our results showed that taller people had higher risk of HNCA in general, and oro- and hypopharyngeal cancers in particular. Green and colleagues also showed a direct association between height and overall cancer risk in the Million Women Study, and confirmed it by performing a meta-analysis of previous publications (26). The effect of height on overall cancer risk is hypothesized to be due to increased IGF-1 (26, 27). In the Million Women Study, cancers of the mouth and pharynx did not show a significant association with height (26). However, most other studies on the head and neck cancers have shown an inverse association between height and head and neck cancers (28, 29). It is difficult to explain these differences, but the INHANCE study suggested that the inverse association was much weaker in the higher education group, and in studies from the US (28). They hypothesized that at least part of the inverse association with height might be due to residual confounding by SES, which is less evident in groups with higher education. The NIH-AARP cohort population is a relatively homogenous group of middle- to upper-class Americans in urban centers who are on average more educated than the general US population (30).

Our study had several strengths: we had more incident cases of HNCA and its subsites (except for nasopharynx) than previous prospective studies, which allowed us to perform subsite analyses with adequate power. We were also able to look at different anthropometric measures, BMI at different ages, and adjust for many confounders. We also were able to stratify by both present and past smoking habits. Our main limitation is the self-reported anthropometric measurements, which may lead to some misclassification. We were also not able to directly study HPV-associated tumors, although these cancers are mainly among the oro- and hypo-pharyngeal cancers(31), and the different risk factor pattern among the latter group can be due to this etiologic difference. Also, the small number of nasopharyngeal cases did not allow a separate analysis of this group.

Our study confirms findings from previous studies showing that the observed association between leanness and risk of head and neck cancers may be due to confounding or effect modification by other risk factors, particularly smoking. It also shows interesting associations between these cancers and abdominal obesity and height.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crozier E, Sumer BD. Head and neck cancer. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:1031–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curado MP, Hashibe M. Recent changes in the epidemiology of head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:194–200. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832a68ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4550–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A. Prospective investigation of the cigarette smoking-head and neck cancer association by sex. Cancer. 2007;110:1593–601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman ND, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Abnet CC. Alcohol and head and neck cancer risk in a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1469–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehanna H, Beech T, Nicholson T, El-Hariry I, McConkey C, Paleri V, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer--systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013;35:747–55. doi: 10.1002/hed.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SL, Lee YC, Marron M, Agudo A, Ahrens W, Barzan L, et al. The association between change in body mass index and upper aerodigestive tract cancers in the ARCAGE project: multicenter case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1449–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaudet MM, Olshan AF, Chuang SC, Berthiller J, Zhang ZF, Lissowska J, et al. Body mass index and risk of head and neck cancer in a pooled analysis of case-control studies in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) Consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1091–102. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrick JL, Gaudet MM, Weissler MC, Funkhouser WK, Olshan AF. Body mass index and risk of head and neck cancer by race: the Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:160–4. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudet MM, Patel AV, Sun J, Hildebrand JS, McCullough ML, Chen AY, et al. Prospective studies of body mass index with head and neck cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:497–503. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashibe M, Hunt J, Wei M, Buys S, Gren L, Lee YC. Tobacco, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of head and neck cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian (PLCO) cohort. Head Neck. 2013;35:914–22. doi: 10.1002/hed.23052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions : the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1119–25. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabat GC, Chang CJ, Wynder EL. The role of tobacco, alcohol use, and body mass index in oral and pharyngeal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:1137–44. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieto A, Sanchez MJ, Martinez C, Castellsague X, Quintana MJ, Bosch X, et al. Lifetime body mass index and risk of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer by smoking and drinking habits. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1667–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etemadi A, Islami F, Phillips DH, Godschalk R, Golozar A, Kamangar F, et al. Variation in PAH-related DNA adduct levels among non-smokers: the role of multiple genetic polymorphisms and nucleotide excision repair phenotype. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2738–47. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizoue T, Kasai H, Kubo T, Tokunaga S. Leanness, smoking, and enhanced oxidative DNA damage. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:582–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etemadi A, Golozar A, Kamangar F, Freedman ND, Shakeri R, Matthews C, et al. Large body size and sedentary lifestyle during childhood and early adulthood and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high-risk population. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1593–600. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbartabartoori M, Lean ME, Hankey CR. Relationships between cigarette smoking, body size and body shape. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:236–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canoy D, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Day N, et al. Cigarette smoking and fat distribution in 21,828 British men and women: a population-based study. Obes Res. 2005;13:1466–75. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett-Connor E, Khaw KT. Cigarette smoking and increased central adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:783–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-10-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green J, Cairns BJ, Casabonne D, Wright FL, Reeves G, Beral V. Height and cancer incidence in the Million Women Study: prospective cohort, and meta-analysis of prospective studies of height and total cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:785–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renehan AG. Height and cancer: consistent links, but mechanisms unclear. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:716–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leoncini E, Ricciardi W, Cadoni G, Arzani D, Petrelli L, Paludetti G, et al. Adult height and head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis within the INHANCE Consortium. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9863-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Talamini R, Franceschi S. Anthropometric measures and risk of cancers of the upper digestive and respiratory tract. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:219–27. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doubeni CA, Schootman M, Major JM, Stone RA, Laiyemo AO, Park Y, et al. Health status, neighborhood socioeconomic context, and premature mortality in the United States: The National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:680–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.