SUMMARY

As sessile organisms, plants must adapt to variations in the environment. Environmental stress triggers various responses, including growth inhibition, mediated by the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA). The mechanisms that integrate stress responses with growth are poorly understood. Here, we discovered that the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) kinase phosphorylates PYL ABA receptors at a conserved serine residue to prevent activation of the stress response in unstressed plants. This phosphorylation disrupts PYL association with ABA and with PP2C phosphatase effectors, leading to inactivation of SnRK2 kinases. Under stress, ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate Raptor, a component of the TOR complex, triggering TOR complex dissociation and inhibition. Thus, TOR signaling represses ABA signaling and stress responses in unstressed conditions, whereas ABA signaling represses TOR signaling and growth during times of stress. Plants utilize this conserved phospho-regulatory feedback mechanism to optimize the balance of growth and stress responses.

Keywords: Abscisic Acid, Target of Rapamycin, Phosphorylation, SnRK2, Raptor, ABA Receptor

In Brief

Wang et al., reveal that the TOR kinase phosphorylates ABA receptors to repress stress responses under unstressed conditions and to promote growth recovery once environmental stresses subside. Under stress conditions, SnRK2s phosphorylate Raptor, a regulatory component in the TOR complex, to prevent growth by inhibiting TOR activity.

INTRODUCTION

Upon sensing environmental stresses, plants sacrifice growth and activate protective stress responses. The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays a critical role in integrating a wide range of stress signals and controlling downstream stress responses (Antoni et al., 2011; Assmann and Jegla, 2016; Chater et al., 2015; Cutler et al., 2009; Hubbard et al., 2010; Lumba et al., 2014; Raghavendra et al., 2010; Umezawa et al., 2010; Zhu, 2016). ABA reduces transpiration and photosynthesis (Munemasa et al., 2015; Roelfsema et al., 2012), reprograms metabolism to accumulate osmolytes, inhibits growth (Julkowska and Testerink, 2015), and promotes dormancy and senescence to adapt to and survive severe stress (Zhao et al., 2016).

In response to environmental stresses such as drought, ABA accumulates rapidly and binds receptors in the PYR1/PYL/RCAR family of proteins (herein referred to as PYLs)(Cutler et al., 2009). The ABA-PYL receptor complex subsequently inhibits downstream protein phosphatases in clade A of the PP2C family, which includes ABI1, ABI2, HAB1, HAB2, PP2CA, and AHG1 (Fujii et al., 2009; Gonzalez-Guzman et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). PP2C inhibition releases sucrose non-fermenting-1 (SNF1) related protein kinase-2s (SnRK2s), which phosphorylate downstream effectors to initiate protective responses such as stomatal closure and gene expression reprogramming (Geiger et al., 2009; Grondin et al., 2015; Umezawa et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). ABA also has important roles in regulating plant growth and development (Cutler et al., 2009; Humplík et al., 2017). ABA promotes seeds dormancy and inhibits growth of young seedlings by reducing polar auxin transport (Shkolnik-Inbar and Bar-Zvi, 2010), or by affecting the expression of auxin responsive genes (Liu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). ABA signaling also cross-talks with brassinosteroid signaling in controlling seed germination (Hu and Yu, 2014; Zhang et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2013), growth, and grain-filling (Gui et al., 2016; Clouse, 2016). Under stress conditions, ABA signaling interacts with gibberellin and auxin signaling pathways, and controls lateral root development (De Smet et al., 2003; Gou et al., 2010; Duan et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). ABA also promotes the senescence and abscission in adult plants by inducing ethylene biosynthesis and by ethylene-independent mechanisms (Liu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016).

There are 14 members in the PYL family in Arabidopsis. Although PYR1 and PYL1-4 interact with and inhibit PP2Cs only in the presence of ABA, the remaining PYLs can interact with and inhibit PP2Cs in vitro even without ABA (Fujii et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2011). It is not known how these latter PYLs, with ABA-independent activities, are kept inactive in plants to prevent ABA responses in the absence of stress. Although single gene mutations in most PYLs do not significantly compromise ABA signaling, mutations in multiple PYL genes lead to strong ABA resistant phenotypes (Gonzalez-Guzman et al., 2012; Park et al., 2009), suggesting that the PYLs have redundant functions. Several PYLs, particularly PYL3, can also sense the ABA catabolite phaseic acid (Weng et al., 2016).

Plant growth is inhibited under stress to maximize stress responses and ensure survival. Upon cessation of environmental stress, plants must quickly deactivate protective stress responses and stimulate growth recovery mechanisms. How plants switch between growth processes and stress responses is a long-standing and major question in plant biology (Achard et al., 2006). Although the mechanism underlying this switch is still unclear, it is known to involve the intricate regulation of key factors for growth control.

Target of Rapamycin (TOR) is an evolutionarily conserved master regulator that integrates energy, growth, hormone and stress signaling to promote growth in all eukaryotes (Dobrenel et al., 2016; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012; Shimobayashi and Hall, 2014; Xiong et al., 2013). In plants, the TOR complex has essential roles in regulating cell proliferation, cell size, development, protein synthesis, transcription and metabolism (Bogre et al., 2013; Caldana et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2012; Schepetilnikov et al., 2013; Schepetilnikov et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2013; Xiong and Sheen, 2012). TOR controls translational initiation by phosphorylating the translation initiation factor elF3h and 40S ribosomal protein S6 kinases (S6Ks)(Mahfouz et al., 2006; Schepetilnikov et al., 2013; Schepetilnikov et al., 2011). The activation of both the root and shoot meristems requires TOR kinase (Li et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2013). In the root meristem, TOR phosphorylates the E2Fa transcription factor to regulate the expression of genes involved in metabolism, cell cycle, transcription, signaling, transport and protein folding (Xiong et al., 2013). The plant growth hormone auxin stimulates TOR activity through a physical interaction between TOR and auxin-activated Rho-like GTPase 2 (ROP 2) to promote the activation of shoot meristem (Li et al., 2017; Schepetilnikov et al., 2017). TOR also mediates the crosstalk between sugar signaling and brassinosteroid (BR) signaling by regulating the stability of BR signaling key transcription factor BZR1, thus allowing carbon availability to control growth-promotion hormonal programs to ensure supply-demand balance in plant growth (Zhang et al., 2016). Thus, TOR represents a potential regulator of the switch between the stress response and growth.

Here, we report that TOR kinase phosphorylates PYL ABA receptors in the absence of stress. This phosphorylation negatively regulates PYL activity to inhibit ABA binding and its interaction with downstream PP2C enzymes. Our results suggest that this negative regulation is important for preventing ABA and stress signaling by ABA-independent PYLs when there is no stress. Under stress, ABA triggers PYL-mediated activation of SnRK2s, which phosphorylate the TOR regulator Raptor and thereby inhibit TOR activity to contribute to ABA- and stress-induced growth inhibition. When stress subsides, TOR phosphorylation of PYLs is critical for growth recovery. Our results uncover a phosphorylation-dependent regulatory loop between ABA core signaling and the TOR complex. Plants utilize this conserved mechanism to repress stress and ABA responses under unstressed conditions, to inhibit growth under stress, and to promote growth recovery once environmental stresses subside.

RESULTS

Phosphorylation of PYLs at a Conserved Serine Residue Abolishes Their Activity

To test whether phosphorylation regulates the activity of PYL ABA receptors, we performed a large-scale phosphoproteomic comparison of Arabidopsis seedlings treated with or without ABA. After protein extraction and digestion, phosphopeptides were enriched using Fe-IMAC StageTips (Tsai et al., 2014). Our phosphoproteomics data uncovered a PYL4 phosphopeptide containing phosphorylated Ser114 in control seedlings, but not in ABA-treated seedlings (Figure 1A, ProteomeXchange, PXD003746). To investigate phosphorylation at this site in other PYL proteins, we uncovered additional phosphopeptides by fractionating enriched phosphopeptides with basic pH reverse phase StageTips (Dimayacyac-Esleta et al., 2015). We identified a total of 47,126 phosphopeptides corresponding to 37,387 phosphorylation sites (22,346 class I sites) using MaxQuant software. ABA treatment abolished phosphorylation of Ser119 in PYL1 and Ser94 in PYL9 (Figure S1A), which correspond to PYL4 Ser114. However, ABA treatment did not substantially affect phosphorylation of Ser9 in PYL1 (Figure S1B). We also measured the phosphorylation of PYL1 immunoprecipitated from transgenic pyr1pyl1pyl2pyl4 (pyr1pyl124) quadruple mutant plants carrying native promoter-driven, wild-type PYL1-Myc. Similar to PYL4 (Figure 1A), ABA treatment abolished the Ser119 phosphorylation in PYL1-Myc (Figure S1C). The residue corresponding to PYL1 Ser119/PYL4 Ser114 is located within the ABA binding pocket and is conserved within all 14 PYLs in Arabidopsis; this residue promotes binding of the ABA dimethyl group (Melcher et al., 2009; Miyazono et al., 2009).

Figure 1. PYL Phosphorylation and the Effects of Non-Phosphorylatable and Phosphomimic Mutations on PYL Function In Vitro.

(A) Quantitative analysis of phosphopeptide containing Ser114 in PYL4 in seedlings with or without ABA treatment. A phosphopeptide containing phosphorylated Thr481 in AT3G02750 was used as a control. N.D., not identified in the samples. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(B) Phosphomimic mutations of PYL1 and PYL4 abolished their activity in transient reporter gene expression assays in protoplasts. RD29B::LUC and ZmUBQ::GUS were used as the ABA-responsive reporter and internal control, respectively. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated for 5 hours under light and in the absence of ABA (open bars) or in the presence of 5 μM ABA (filled bars). Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). Anti-His tag immunoblot shows the levels of histidine-tagged wild type and mutated PYL1 and PYL4 proteins in the protoplasts.

(C) PYL1S119D is an inactive ABA receptor and cannot inhibit ABI1 in an in vitro reconstitution of the ABA signaling pathway. The autoradiography (upper panel) and coomassie staining (lower panel) show ABF2 fragment phosphorylation and protein loading, respectively.

(D) Phosphomimic mutants of PYL1 and PYL4 cannot inhibit ABI1 phosphatase activity. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(E) PYL1 and PYL1S119A but not the phosphomimic mutant PYL1S119D interact with ABI1 in a yeast two-hybrid assay.

(F) Dose-dependent curves show the effect of mutations at Ser119 on ABA binding affinity of PYL1 in TSA assay. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments.

(G–I) Binding isotherms showing the effect of mutations at Ser119 on ABA binding affinity of PYL1 in MST assay. Equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) used to indicate the binding affinity between PYL protein and ABA. Data shown is representative of two independent experiments.

See also Figure S1.

To determine the role of this conserved serine in the PYL family, we generated a series of PYL mutants for testing in a reporter assay in protoplasts that monitors PYL-mediated inhibition of PP2Cs (Fujii et al., 2009). Specifically, we mutated the serine (S) to a similarly sized, non-phosphorylatable and neutral alanine (A) or cysteine (C), to a larger, non-phosphorylatable, neutral leucine (L) or glutamine (Q), or to a negatively charged, phosphomimic aspartic acid (D) or glutamic acid (E). As reported previously (Fujii et al., 2009), ABA relieved ABI1-mediated repression of SnRK2.6 in protoplasts expressing wild type PYL1 or PYL4, and induced the ABA-responsive reporter RD29B-LUC (Figure 1B, lanes 3 and 6). We found that ABA also induced RD29B-LUC in protoplasts expressing PYL4S114A, PYL1S119A (Figure 1B, lanes 4 and 7) or PYL1S119C (Figure S1D), but not in protoplasts expressing the phosphomimic mutants PYL1S119D and PYL4S114D, or the larger side chain mutants PYL1S119L and PYL1S119Q (Figure 1B, lanes 5 and 8, Figure S1D). In contrast, a phosphomimic substitution at Thr118 in PYL1 did not affect ABA-dependent induction (Figure S1B). These data implied that a small, uncharged side chain (S, A, C) at position 119 is required for ABA binding. Phosphorylation of Ser119, which enlarges and negatively charges the side chain, or substitution with larger side chain and/or charged amino acids (L, Q, D, E) block the ABA binding pocket and decrease ABA binding affinity. In addition, PYL4S114D also abolished ABA-dependent inhibition of other clade A PP2C phosphatases, including HAB1, PP2CA, HAI3, and AHG1 (Figure S1E). Further, phosphomimic substitutions at the conserved serine in all other PYLs eliminated or substantially reduced ABA-dependent induction of RD29B-LUC (Figure S1E). These results suggest that phosphorylation of the conserved serine alters the ABA binding pocket and negatively regulates PYLs function in vivo.

We then examined how phosphorylation affects PYL activity using a modified in vitro system that reconstitutes the core signaling pathway ABA-PYL-ABI1-SnRK2.6-ABF2 (Abscisic Acid Responsive Elements-Binding Factor 2) (Fujii et al., 2009). In this system, phosphorylation of the well-characterized SnRK2 substrate ABF2 is monitored to evaluate SnRK2.6 activity. Recombinant GST-ABI1 inhibited SnRK2.6 activity and ABF2 phosphorylation (Figure 1C, lane 3), and addition of recombinant wild type PYL1 reversed ABI1-mediated inhibition of SnRK2.6 in an ABA-dependent manner (Figure 1C, lane 5). PYL1S119A also triggered ABA-dependent inhibition of ABI1 and induced ABF2 phosphorylation, similar to wild type PYL1 (Figure 1C, lane 7). In contrast, PYL1S119D lost ABA-dependent inhibition of ABI1, and ABF2 was not phosphorylated (Figure 1C, lane 9). Consistent with this finding, PYL1S119D could not inhibit ABI1 phosphatase activity in vitro, even in the presence of ABA (Figure 1D). These data further suggest that phosphorylation of PYL1 at the conserved serine prevents ABA-dependent inhibition of PP2Cs.

To determine if the phosphomimic mutations at the conserved serine affect the interaction between the ABI1 and PYL proteins, we used a yeast two-hybrid assay. We found that the phosphomimic mutation in PYL1 abolished the ABA-dependent interaction between ABI1 and PYL1 (Figure 1E). The phosphomimic mutations also eliminated the ABA-dependent interactions between ABI1 and PYR1, PYL2, PYL3, and PYL4, and the ABA-independent interactions between ABI1 and PYL7, PYL9, PYL11, PYL12 (Figure S1F). Interestingly, the ABA-independent interactions between ABI1 and PYL5, PYL6, PYL8 and PYL10 were only partially inhibited or unaffected by these phosphomimic mutations in the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure S1G). However, phosphomimic mutated forms of PYL10 prevented HAB1 inhibition (Figure 2A). We used an alpha screen assay to re-investigate the physical interaction between PYL10 and HAB1 and ABI1 (Melcher et al., 2009), and found that the S88D and S88E mutations abolished PYL10 interactions with these PP2C phosphatases (Figure 2B and 2C). Overall, these results suggest that phosphorylation of the conserved serine in the PYLs abolishes the ABA-dependent and ABA-independent physical interactions with PP2Cs.

Figure 2. Phosphomimic Mutations Abolish PYL Activities.

(A) Phosphomimic mutants of PYL10 cannot inhibit the phosphatase activity of HAB1. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(B and C) Phosphomimic mutants of PYL10 cannot interact with HAB1(B) or ABI1(C) in alpha screen assay. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(D) Dose-dependent curves showing the effect of mutations at Ser88 on the binding affinity of PYL10 for ABA in TAS assay. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(E and F) Binding isotherms showing the effect of mutations at Ser88 on the binding affinity of PYL10 for ABA in MST assay. Data shown is representative of two independent experiments.

See also Figure S2.

Phosphomimic mutations of Ser119 in PYLs Inhibit ABA binding

To determine how the phosphomimic substitutions abolish PYL function, we evaluated the ABA binding activity of the PYL proteins by a Thermal Stability Shift Assay (TSA) and a Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) assay. We found that PYL1S119D did not bind ABA in the TSA assay, whereas PYL1S119A bound ABA, albeit with lower affinity than wild type PYL1 (Figure 1F). This finding is consistent with the reduced capacity of PYL1S119A to inhibit ABI1 and activate the reporter in the protoplast assay (Figure 1B). The MST assay revealed that wild type PYL1 and PYL1S119A bind ABA with affinities of 63.7 and 219 μM, respectively (Figure 1G and 1H). In contrast, the phosphomimic mutated PYL1S119D did not show any ABA binding activity (Figure 1I). Similarly, PYL10S88D and PYL10S88E did not show any ABA binding activity in the TSA and MST assays (Figure 2D–2F). These results suggest that phosphorylation of PYLs at the conserved serine residue negatively regulates ABA perception and signaling by inhibiting ABA binding. This negative regulation applies not only to the PYLs that are fully dependent on ABA but also to the PYLs that have ABA-independent activities.

To determine if ABA receptor phospho-regulation is conserved, we performed an in silico homology search in land plants. We found that the serine residue corresponding to Ser119 in PYL1 is conserved across all 121 PYLs from 12 different species (Figure S2A and S2B). This finding suggests that phosphorylation-based inhibition of the PYLs-ABA interaction is conserved across land plants.

Phosphorylation of PYLs Ser119 Promotes Growth Recovery After Stress

Next, we evaluated how PYL phosphorylation affects the response to ABA in planta. We generated transgenic plants carrying native promoter-driven wild type PYL1, PYL1S119A and PYL1S119D in pyr1pyl1pyl2pyl4 (pyr1pyl124) quadruple mutant plants. Transgenic expression of wild type PYL1 or PYL1S119A complemented the ABA-hyposensitive phenotypes of the quadruple mutant in germination, root elongation and seedling growth (Figure 3A, 3B, and S3A–S3E). In contrast, transgenic expression of PYL1S119D did not complement the ABA-insensitive phenotypes of pyr1pyl124 mutant plants (Figure 3A, 3B, and S3A–S3E), even though transgene expression levels were similar to wild type PYL1 or PYL1S119A plants (Figure S3F). These data from transgenic plants together with the in vitro assay results, demonstrate that phosphomimic mutated PYLs are non-functional receptors.

Figure 3. Effects of Non-Phosphorylatable and Phosphomimic Mutations on PYL1 Function In Vivo.

(A) Photographs of seeds after 5 days of germination and growth on 1/2 Murashige-Skoog (MS) medium containing 3 μM ABA.

(B) 10-day-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium with 10 μM ABA (right panel) or without ABA (left panel).

(C) Photographs of seedlings after 5 days of growth recovery. The seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 10 μM ABA were transferred to 1/2 MS medium without ABA. Data shown is representative of six independent experiments.

(D) Fresh weight of seedlings after 3 days recovery growth on 1/2 MS medium. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 6). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(E) Rosetta diameter of seedlings after indicated time of recovery growth on 1/2 MS medium. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 6). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

See also Figure S3.

We further investigated how loss of Ser119 phosphorylation affects growth and stress responses in transgenic plants carrying PYL1S119A and wild type PYL1. Both pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119A and pyr1pyl124-PYL1 showed arrested seedling growth and yellow leaves when grown on medium containing 10 μM ABA (Figure 3B and S3C–S3E). Upon transfer to fresh medium without ABA, pyr1pyl124-PYL1 seedlings lost the ABA-induced leaf yellowing after 5 days of recovery. In contrast, the greening of yellow leaves was abolished in pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119A seedlings (Figure 3C). The pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119A seedlings also showed delayed recovery from osmotic stress induced by mannitol treatment, when transferred from medium containing 300 mM mannitol to fresh medium without mannitol (Figure 3D and 3E). Thus, pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119A seedlings show delayed growth recovery compared to pyr1pyl124-PYL1 seedlings.

Target of Rapamycin (TOR) Kinase Phosphorylates PYLs and Negatively Regulates ABA Signaling in the Absence of Stress

Our findings suggest that phosphorylation of Ser119 in PYL1 negatively regulates ABA and stress signaling, and positively regulates recovery. Therefore, we hypothesized that the kinase targeting this site should promote plant growth. To test this hypothesis, we screened protein kinases that interact with PYL1, that are co-expressed with PYL1, or that were reported to promote plant growth. We screened over 30 protein kinases using an in vitro kinase assay and found that several kinases, such as CKL3 and AT1G51850, could phosphorylate PYLs (Figure S4A). However, only the immunoprecipitated Target of Rapamycin (TOR) kinase could phosphorylate recombinant PYL1 at Ser119 in vitro (Figure 4A). Only one phosphopeptide, which contains Ser119, from PYL1 was detected by mass spectrometry in the TOR kinase reaction products after trypsin digestion (Figure S4B). Furthermore, the S119A substitution within PYL1 substantially reduced phosphorylation by TOR kinase, but not the phosphorylation by CKL3 or AT1G51850 (Figure 4B, S4A, and S4C). Immunoprecipitated TOR complex phosphorylated all 11 of the recombinant PYL proteins that we tested, whereas the TOR inhibitors PP242 and Torin2 substantially reduced PYL phosphorylation (Figure 4A and S4D). It is notable that the PYL phosphosite regions do not contain any known TOR recognition motifs (Hsu et al., 2011). Plant TORs might recognize a unique phosphorylation motif in the PYLs that differs from animal TORs.

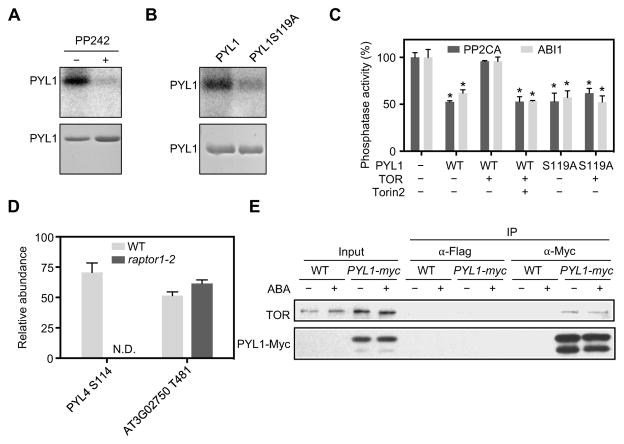

Figure 4. TOR Kinase Phosphorylates PYLs.

(A) Immunoprecipitated TOR kinase phosphorylates recombinant PYL1 and TOR inhibitor PP242 inhibit the PYL1 phosphorylation. Autoradiograph (upper panel) and Coomassie staining (lower panel) show phosphorylation and loading of purified PYL1.

(B) Phosphorylation of recombinant wild type PYL1 and PYL1S119A by immunoprecipitated TOR kinase. Autoradiograph (upper panel) and Coomassie staining (lower panel) show phosphorylation and loading of purified PYL1 and PYL1S119A.

(C) Phosphorylation by TOR kinase inhibits the activity of PYL1 but not PYLS119A. Inhibition of ABI1 and PP2CA phosphatase activity was used to indicate the PYL1 activity. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(D) Quantitative analysis of PYL4 phosphopeptide in wild type and raptor1-2 seedlings. A phosphopeptide containing phosphorylated Thr481 in AT3G02750 was used as a control. N.D., not identified in the samples. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3).

(E) Co-immunoprecipitation assay showing the interaction between TOR and PYL1 in pyr1pyl124-PYL1-Myc transgenic plants.

See also Figure S4.

The activity of clade A PP2Cs is inhibited by PYL1 in the presence of ABA. We found that immunoprecipitated TOR kinase and ATP prevented the ABA-dependent inhibition of PP2C and ABI1 by PYL1, but not by the non-phosphorylatable PYL1S119A (Figure 4C). Further, Torin2 abolished the suppressive effect of TOR in this assay (Figure 4C). These data suggest that phosphorylation of PYL by TOR suppresses PYL-mediated inhibition of PP2Cs.

To examine the relationship between TOR kinase activity and PYL phosphorylation in vivo, we measured the phosphorylation status of PYLs in a raptor1-2 mutant plant by quantitative phosphoproteomics. These mutant plants lack the Regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (RaptorB), and display reduced TOR kinase activity, based on the phosphorylation status of T449 in S6 protein kinase 6 (S6K1), a well-characterized TOR kinase target site, in vivo (Figure S4E). We detected the phosphopeptide QVHVVSGLPAASpSTER from PYL4, which contains the phosphosite Ser114, in wild type seedlings, but not in raptor1-2 mutant seedlings (Figure 4D). In addition, TOR co-immunoprecipitated with PYL1-Myc from pyr1pyl124-PYL1-Myc seedlings (Figure 4E), supporting a PYL-TOR physical interaction. These data strongly suggest that PYL ABA receptors are TOR kinase substrates in vivo, with the conserved serine residues corresponding to Ser119 in PYL1 as TOR kinase targets.

We hypothesized that TOR kinase may negatively modulate ABA signaling and stress responses, since TOR phosphorylation at the conserved serine in PYLs negatively regulates PYL function. To test this hypothesis, we measured ABA responses in an estradiol inducible TOR RNAi line, es-tor (Xiong and Sheen, 2012), and in the raptor1-2 mutant plants. After ABA treatment, estradiol-treated es-tor seedlings and raptor1-2 seedlings lost more chlorophyll than wild type seedlings (Figure 5A and 5B). The raptor1-2 mutants also showed ABA hypersensitivity in germination and early seedling growth (Figure 5C). Thus, depletion of TOR or loss of RaptorB triggers ABA hypersensitive phenotypes compared to wild type plants.

Figure 5. TOR Kinase Inhibition Enhances ABA Signaling.

(A) Chlorophyll content of WT and es-tor seedlings 6 days after growing in a liquid medium or a medium supplemented with different ABA concentrations. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 6). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(B) Total chlorophyll content of the seedlings 8 days after transfer to the medium containing 10 μM ABA. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 6). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(C) Photographs of WT and raptor1 plants after 5 days of germination and growth on 1/2 MS medium or 1/2 MS medium containing 0.5 μM ABA.

(D) In-gel kinase assay showing SnRK2 activity in the es-tor line, raptor1 mutant or wild type after 0, 10 or 30 min of 10 μM ABA treatment. The position of SnRK2.6 is indicated by an arrowhead. Radioactivity levels of the band (arrowhead) were normalized using wild type after 10 min treatment. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Anti-TOR and anti-SnRK2.6 immunoblots show TOR and SnRK2 protein levels in the samples.

(E) In-gel kinase assay showing ABA induced SnRK2 activity in wild type seedlings preincubated with DMSO, Rapamycin or PP242. The position of SnRK2.6 is indicated by an arrowhead. Radioactivity levels of the band (arrowhead) were normalized using wild type after 10 min treatment. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Anti-TOR and anti-SnRK2.6 immunoblots show TOR and SnRK2 protein levels in the samples.

(F) In-gel kinase assay showing the activities of SnRK2s in the es-tor seedlings with 3 days of DMSO or estradiol incubation. Arrowhead indicates the position of SnRK2.6. Radioactivity of the band indicated by arrowhead was normalized by comparing the radioactivity band in the DMSO treated sample. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Anti-TOR and anti-SnRK2.6 immunoblots show TOR and SnRK2 protein levels in the samples.

(G) ABA responsive gene expression in the es-tor and raptor1 seedlings with 3 days of DMSO or estradiol treatment or with 6 hours treatment with rapamycin. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(H) Osmotic stress sensitivity as measured by electrolyte leakage in wild type, es-tor and raptor1 plants treated with 30% PEG. Error bars indicate s.d. (n = 6).

See also Figure S5.

Next, we determined if loss of TOR or RaptorB function affects ABA signaling. To detect ABA-induced SnRK2 activation in seedlings, we used an in-gel assay to monitor SnRK2 activity on histone substrates (Fujii et al., 2007). After ABA application, estradiol-treated es-tor and raptor1-2 seedlings showed higher levels of SnRK2 activity than wild type (Figure 5D, upper and middle panels). Similarly, pretreatment with the TOR kinase inhibitors rapamycin or PP242 also increased ABA-induced SnRK2 activity compared to control seedlings (Figure 5E). Further, when we increased loading of the protein extract to 200 μg/lane, a 10-fold loading increase relative to that used in Figure 5D and 5E, we detected SnRK2 activity in the es-tor seedlings even without ABA treatment (Figure 5F, lane 2), whereas no SnRK2 activity was detected in the wild type (Figure 5F, lane 1).

Next, we analyzed the transcriptome data of estradiol-treated es-tor plants generated by Xiong et al. (2013) to obtain a transcriptomic profile. Out of the 1,833 up-regulated genes in the es-tor samples (fold change > 2, p < 0.001, Pearson’s Chi-squared test) (Table S1), 1,043 genes are known to be regulated by abiotic stress (Table S2) and 246 genes are known to be induced by ABA treatment (Table S3 and S4). Compared to the entire transcriptome, stress and ABA responsive genes were enriched in the subset of genes that were up-regulated in estradiol-treated es-tor plants (p < 0.001, Pearson’s Chi-squared test) but not in the subset that were down-regulated (Figure S5). Quantitative RT-PCR results verified that the transcript levels of several ABA marker genes, such as RD29A and RD22, were slightly elevated in estradiol-treated es-tor lines, the raptor1-2 mutant, and in wild type seedlings treated with rapamycin, even in the absence of ABA (Figure 5G). Further, when exposed to a high concentration of PEG, the estradiol-treated es-tor and raptor1-2 mutant seedlings show much less electrolyte leakage compared to wild type seedlings (Figure 5H), indicating less stress damage in the es-tor line and raptor1 mutant. Together, these data are consistent with the partial activation of ABA and stress responses in these mutant plants. Thus, inhibition of TOR kinase can partially activate ABA signaling, resulting in SnRK2 activation, induction of stress-responsive gene expression, and increased stress tolerance. The results suggest that TOR kinase phosphorylation of PYLs prevents ABA signaling and stress responses in the absence of stress.

ABA Represses TOR Kinase Activity through SnRK2-mediated Phosphorylation of RaptorB

Our results indicate that TOR kinase plays a critical role to prevent stress signaling under favorable conditions by phosphorylating PYL receptors. Interestingly, PYL receptor phosphorylation was quickly reversed after ABA treatment (Figure 1A and S1A), which suggests that ABA also inhibits TOR. Consistent with this observation, we found that ABA treatment decreased the phosphorylation of recombinant PYL1 and PYL4 by immunoprecipitated TOR in vitro (Figure 6A). ABA treatment also significantly reduced phosphorylation of Thr449 in the TOR substrate S6K1 (Figure 6B). Similar to ABA, osmotic stress induced by mannitol treatment also repressed phosphorylation of Thr449 in S6K1 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. ABA and Stress Inhibits TOR Kinase Activity.

(A) In vitro kinase assay showing ABA inhibition of PYL1 and PYL4 phosphorylation. TOR was immunoprecipitated from 7-day-old seedlings incubated with or without ABA and incubated with recombinant His-Sumo-PYL1 and His-Sumo-PYL4 proteins as substrates. TOR protein levels are indicated by the anti-TOR immunoblot. PYL1/PYL4 protein levels are indicated by Coomassie-stained gel. Band radioactivity levels were normalized to control without ABA and Torin2 treatment. Error bars indicate s.d. (n = 3).

(B) ABA represses phosphorylation of S6K1 at T449 site in seedlings. S6K1-HA was overexpressed in the seedlings to facilitate S6K1 detection using anti-HA immunoblot.

(C) Phosphorylation level of T449 of S6K1 was decreased by mannitol treatment in seedlings. S6K1-HA was overexpressed in the seedlings to facilitate S6K1 detection using anti-HA immunoblot.

(D) ABA inhibition on TOR kinase activity was almost abolished in pyr1pyl12458 sextuple and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutants. S6K1-HA was expressed in protoplasts made from WT, pyr1pyl12458 sextuple and snrk2.2/3/6 triple mutants.

(E) SnRK2.6 but not CDKF phosphorylates a Raptor fragment in vitro. Recombinant GST-Tag fused SnRK2.6 and CDKF were used to phosphorylate AtRaptorB fragment (aa 487-1057) expressed and purified in E. coli in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Autoradiograph (Left) and Coomassie staining (Right) show phosphorylation and loading of purified SnRK2.6, CDKF, and RaptorB. Asterisk indicates partially degraded AtRaptorB.

(F) Quantitative analysis of phosphopeptides containing S897 and S941 in wild type and snrk2 decuple mutant seedlings, with or without ABA treatment. The relative abundance of individual phosphopeptides was normalized to the amount of S941 phosphopeptide in the snrk2 decuple mutant samples with ABA treatment. N.D., not identified in the samples. Error bars indicate s.d. (n = 3).

(G) Phosphorylation of recombinant wild type and S897A mutated AtRaptorB fragments by recombinant SnRK2.6 protein kinase. Autoradiograph (left panel) and Coomassie staining (right panel) show phosphorylation and loading of purified SnRK2.6 and RaptorB fragments. Asterisk indicates partially degraded AtRaptorB.

(H and I) ABA inhibitory effect on TOR kinase can be suppressed by RaptorB overexpression. S6K1-Flag and RaptorB-HA were expressed in protoplasts made from raptor1-2. Band intensities of ABA treated samples were normalized to samples without ABA treatment. Error bars indicate s.d (n = 3). * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

(J) Less RaptorB co-immunoprecipitated with TOR after ABA treatment. CoIP assays were performed using ABA treated or untreated seedlings. Band intensities from ABA treated samples were normalized to samples without ABA treatment. Error bars indicate s.d (n = 3). *** p < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

See also Figure S6.

To study how ABA and stress inhibit TOR kinase activity, we first determined the phosphorylation status of the TOR target S6K1 in mutants lacking components of the ABA core signaling pathway. We expressed S6K1-HA in wild type protoplasts, as well as in snrk2.2/3/6 triple and the pyr1pyl12458 sextuple mutant protoplasts. We found ABA treatment reduced S6K1 Thr449 phosphorylation in wild type protoplasts, and this was almost totally abolished in both the snrk2.2/3/6 triple and the pyr1pyl12458 sextuple mutants (Figure 6D). These data suggest that TOR inhibition induced by ABA depends on the ABA core-signaling pathway.

In yeast and animals, the TORC regulatory component Raptor can be phosphorylated by multiple protein kinases, such as AMPK1, GSK3, and NLK, which then modulates TORC activity (Gwinn et al., 2008; Stretton et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015). We hypothesized that RaptorB may be a direct target of SnRK2s, given that SnRK2s are related to AMPK1 (Zhu, 2016) and that multiple phosphosites were detected in Arabidopsis RaptorB in vivo (ProteomeXchange, PXD003746). To test this hypothesis, we investigated a potential interaction between RaptorB and SnRK2s by the yeast two hybrid assay. We found that RaptorB physically interacts with SnRK2.2, SnRK2.3, SnRK2.6, and SnRK2.8 (Figure S6A). We also found that SnRK2.6, but not a randomly selected protein kinase cyclin-dependent protein kinase CDKF, could phosphorylate a recombinant fragment of RaptorB (Figure 6E). These results suggest that RaptorB is a direct substrate of SnRK2s.

To further confirm the relationship between SnRK2 activity and Raptor phosphorylation in vivo, we measured the phosphorylation status of RaptorB protein in wild type and snrk2 decuple mutant plants (Fujii et al., 2011) by performing MS-based quantitative phosphoproteomics. We found that ABA treatment of wild type seedlings substantially increased the levels of a RaptorB phosphopeptide containing phosphorylated Ser897, but not another phosphopeptide containing phosphorylated Ser941 (Figure 6F). However, Ser897 phosphorylation was not detected under either condition in the snrk2 decuple mutant, which lacks all ten members in SnRK2 family (Figure 6F). Moreover, a Ser-to-Ala substitution at Ser897 dramatically reduced the phosphorylation by SnKR2.6, when compared to the wild type RaptorB fragment (Figure 6G). The phosphorylation of Ser897, along with 7 other serine residues, could be detected by MS in the kinase reaction products after trypsin digestion (Figure S6B and S6C). These data suggest that S897 is a major, though perhaps not a unique, SnRK2 phosphorylation site, and the phosphorylation of S897 is dependent on ABA activated SnRK2s in vivo.

Next, we investigated whether ABA signaling might regulate TOR activity by influencing the association of TOR with RaptorB. We increased the level of RaptorB in wild type protoplasts by introducing a 35S promoter-driven RaptorB construct. We found that increased RaptorB levels impaired ABA-induced TOR inhibition (Figure 6H and 6I, n = 3, p < 0.05, Student’s t test). In addition, we immunoprecipitated the TOR complex from seedlings that were treated with ABA or left untreated. We found that ABA treatment reduced the interaction between RaptorB and TOR, detected by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 6J and S6D, n = 3, p < 0.001, Student’s t test). Our results suggest that ABA-mediated activation of SnRK2.6 leads to phosphorylation of RaptorB to promote disassociation of RaptorB from the TOR complex and inhibit TOR kinase activity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered that TOR kinase regulates ABA perception through phosphorylation of a conserved serine in the ABA receptor PYLs. This phosphorylation abolishes the ABA binding activity of PYLs. Our results suggest that TOR kinase-mediated PYL phosphorylation represents a conserved mechanism to prevent stress signaling under non-stress conditions and desensitizes stress signaling after stress subsides. In addition, our results suggest that ABA and stress inhibit plant growth by activating SnRK2 kinases to phosphorylate RaptorB, a regulatory component of the TOR complex.

TOR kinase is an evolutionarily conserved regulator of growth in eukaryotes. We found that plants with reduced TOR activity are hypersensitive to ABA and display ABA treatment-related phenotypes, including growth arrest, SnRK2 activation, and expression of ABA responsive genes, even in the absence of ABA (Figure 5). These data support a critical role for TOR kinase in suppressing ABA and stress signaling in the absence of stress. Some PYLs in Arabidopsis (PYL5 to PYL12) can bind and inhibit PP2Cs even in the absence of ABA (Fujii et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2011). However, the activation of ABA signaling in the absence of ABA is not observed in wild type seedlings. We found that the phosphomimic mutations at the conserved serine within PYL10 abolishes its ABA-independent interaction with PP2Cs (Figure 2). We propose that TOR-mediated phosphorylation serves as a mechanism to inhibit the activation of the ABA-independent PYLs under non-stress conditions.

Under stress conditions, activated SnRK2s phosphorylate RaptorB to promote the disassociation of the TOR complex. This might represent a mechanism to rapidly amplify ABA signaling. In the presence of ABA, a small fraction of unphosphorylated PYLs bind to ABA first and then activate SnRK2s. SnRK2s inhibit TOR kinase by phosphorylating RaptorB to release the majority of PYLs from phosphorylation. These unphosphorylated PYLs can then bind ABA to rapidly amplify ABA signaling. In addition, an unknown phosphatase may also be activated under stress and contribute to the dephosphorylation of PYLs. TOR kinase inhibition by ABA and osmotic stress also suggest a mechanism through which environmental stresses and ABA inhibit plant growth. Osmotic stress represses TOR-mediated S6K1 phosphorylation (Figure 6C) and thereby inhibits S6K1 activity (Mahfouz et al., 2006). Because TOR-mediated phosphorylation activates S6K1 and the initiation of translation (Holz et al., 2005), our findings suggest a role for SnRK2s in reprogramming translation in response to ABA and osmotic stress. The inhibition of TOR may also cause repression of BR signaling (Xiong et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016) and impairment of auxin signaling (Li et al., 2017; Schepetilnikov et al., 2017). The DELLA family of growth inhibitory nuclear proteins play important roles in mediating growth inhibition by salt stress, ABA, and ethylene (Achard et al., 2006). Future research will determine how ABA inhibition of TOR kinase may be coordinated with the stabilization of DELLA proteins to inhibit plant growth during stress.

As a key regulator of energy, metabolism, cell division and growth, TOR kinase activity is tightly controlled when plants respond to both internal and environmental stimuli. Raptor is a regulatory component in the TOR complex in both animal and yeast cells. Upon energy stress, AMPK phosphorylates Raptor and in turn inhibits the mTORC1 pathway and suppresses cell growth and biosynthetic processes (Gwinn et al., 2008). Nemo-like kinase (NLK), an osmotic and oxidative stress activated protein kinase, also represses TORC1 through Raptor phosphorylation (Yuan et al., 2015). In addition, ERK1/2, GSK3, Intestinal Cell Kinase (ICK), and S6K1 phosphorylate Raptor to modulate TOR activity (Carriere et al., 2008; Carriere et al., 2011; Stretton et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2012). However, the functional relationship between Raptor phosphorylation and TORC regulation in plants had remained unclear. Here, we discovered that plant specific, stress-activated protein kinases, SnRK2s, phosphorylate Raptor (Figure 6E) to cause TOR inhibition, possibly by promoting the disassociation of the TOR complex in plants (Figure 6J). Our results suggest that Raptor phosphorylation by stress-activated protein kinases is a conserved mechanism for the regulation of TOR and growth in eukaryotic organisms.

TOR phosphorylation of PYLs prevents activation of stress responses when stress is absent. On the other hand, Raptor phosphorylation by stress- and ABA-activated SnRK2s is a mechanism that prevents plant growth under unfavorable conditions to conserve energy and ensure survival. The phosphorylation of PYLs can also switch off ABA signaling during stress recovery in plants. We observed a defect in growth recovery in transgenic plants carrying a non-phosphorylatable PYL1S119A (Figure 3). As the serine corresponding to Ser119 in PYL1 is conserved in all 121 PYLs identified in 12 different species (Figure S2), the phospho-regulation of PYLs appears to be highly conserved in land plants. We propose that the phosphorylation loop between the ABA core signaling components and the TOR complex represents a critical mechanism that balances stress and growth responses for plants to adapt to continuously changing environments (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Model illustrating how TOR kinase and PYL phosphorylation balances growth and stress response in plants

STAR★METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody | ||

|

| ||

| Anti-Myc Antibody | Millipore | 05-724 |

| SnRK2.6 | Agrisera | AS13 2635 |

| HIS | Sigma-Aldrich | H1029 |

| TOR | Xiong and Sheen, 2012 | N/A |

| Anti-HA tag antibody | Abcam | ab9110 |

| S6K1 p-T449 | Agrisera | AS13 2664 |

| Anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | F1804 |

| Anti-GFP | Sigma-Aldrich | 11814460001 |

| Anti-Actin antibody | Abcam | ab197345 |

| Anti-RatporB | This study | N/A |

|

| ||

| Chemicals | ||

|

| ||

| Abscisic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | A1049 |

| Luciferase Assay Reagent | Promega | E1483 |

| Phosphatase substrate | Sigma-Aldrich | P4744 |

| D-Mannitol | Sigma-Aldrich | M4125 |

| PP242 | Sigma-Aldrich | P0037 |

| Torin2 | Selleckchem | S2817 |

| Estradiol | Sigma-Aldrich | E8875 |

| Rapamycin | Sigma-Aldrich | R8781 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor 3 | Sigma-Aldrich | P0044 |

| SnRK2.6 phosphopeptide | Fujii et al., 2009 | HSQPKpSTVGTP |

|

| ||

| Recombinant DNAs | ||

| Recombinant DNAs provided in Table S5 | ||

|

| ||

| Deposited Data | ||

|

| ||

| Raw Imaging Files | This study, Mendeley Data | doi:10.17632/2zchtvbv58.1 |

|

| ||

| Experimental Model and Subject Details | ||

|

| ||

| pyr1pyl12458 | Gonzalez-Guzman., 2012 | N/A |

| pyr1pyl124 | Park et al., 2009 | N/A |

| pyr1pyl124-PYL1-myc | This study | N/A |

| pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119A-myc | This study | N/A |

| pyr1pyl124-PYL1S119D-myc | This study | N/A |

| snrk2.2/2.3/2.6 | Fujii et al., 2009 | N/A |

| snrk2.1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9/10 | Fujii et al., 2011 | N/A |

| es-tor | Xiong and Sheen 2012 | N/A |

| SnRK2.6-GFP | Wang et al., 2015 | N/A |

| S6K1-HA | Xiong et al., 2013 | N/A |

| S6K1-FLAG | Xiong and Sheen 2012 | N/A |

| raptor1-1 | Deprost et al., 2005 | SALK_078159 |

| raptor1-2 | Deprost et al., 2005 | SALK_006431 |

| Sequenced Based Reagents | ||

|

| ||

| Primers provided in Table S6 | ||

|

| ||

| Software | ||

|

| ||

| MaxQuant | Cox and Mann, 2008 | http://www.coxdocs.org/ |

| SEQUEST | Thermo Fisher Scientific | |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software Inc | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Image Lab | Bio-Rad Laboratories | N/A |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jian-Kang Zhu (jkzhu@sibs.ac.cn).

METHODS DETAILS

Generation of the es-tor Mutant

es-tor seeds were geminated in liquid medium (1/2 MS, 1 % glucose) under 75 μmol m−2 s−2 light intensity. After germination, estradiol was added to the medium at a final concentration of 10 μM to induce silencing of the TOR gene in es-tor transgenic plants (Xiong and Sheen., 2012). Three days post-induction, ABA was added at the indicated final concentrations for the indicated lengths of time.

Germination or Growth under ABA and Mannitol Treatment

Seeds were surface-sterilized for 10 min in 20% bleach, and then rinsed four times in sterile-deionized water. For germination assays, sterilized seeds were grown on medium containing 1/2 MS nutrients (PhytoTech), 1% sucrose, pH 5.7, with or without the indicated concentration of ABA, and kept at 4 °C for 3 days. Radicle emergence was analyzed 72 hours after placing the plates in a Percival CU36L5 incubator at 23°C under a 16 hours light/8 hours dark photoperiod. Photographs of seedlings were taken at indicated times after taken to light. For growth assays, sterilized seeds were grown vertically on 0.6% Phytagel containing 1/2 MS, 1% sucrose, pH5.7, and kept at 4 °C for 3 days. Seedlings were grown vertically for 3–4 days and then transferred to medium with or without 10 μM ABA. Root length, fresh weight and chlorophyll content were measured at the indicated days. For recovery growth, vertically grown seedlings were transferred from plates with 10 μM ABA, or 300 mM mannitol to 0.6% Phytagel containing 1/2 MS, 5% sucrose, pH5.7, and were grown vertically for 5 days.

To detect the effect of ABA and mannitol on TOR kinase activity, 7-day-old S6K1-HA transgenic seedlings grown in 6-well plates containing 1ml liquid medium (1/2 MS, 0.5% sucrose, pH5.7) were treated with 50μM ABA for the indicated times or indicated concentrations of mannitol for 6 hours.

Plasmid Constructs

For the transactivation assay, ZmUBQ::GUS, RD29B::LUC; ABF2-HA, SnRK2.6-FLAG, PP2Cs, and His-PYLs were the same as previously reported (Fujii et al, 2009). The plasmids carrying wild type pHBT95-PYLs were used for site-directed mutagenesis using specific primers (Table S6).

pBD-GAL4-PYLs vectors for the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay were the same as reported (Park et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2013), and were used for site-directed mutagenesis using specific primers (Table S6). To generate the vector for Y2H, RaptorB CDS was cloned into the pGADT7 vector between EcoRI and XhoI sites with RaptorB specific primers (Table S6). To generate the pENTR-PYL1 genomic construct, the genomic sequence of PYL1 was amplified using pPYL1pF and pPYL1pR primers (Table S6), and cloned into pENTR vector using pENTR/D-TOPO Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). The genomic sequence of PYL1 genomic was cloned into the pGWB16 binary vector through an LR reaction (Invitrogen).

To generate the construct for RaptorB protein expression in E. coli, the RaptorB CDS fragment (bp 1459 to 3171) was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1vector between EcoRI and SalI sites with gene specific primers (Table S6).

Yeast Two Hybrid Assay

To detect protein interactions between ABI1 and PYLs, pGADT7 plasmids containing ABI1 were co-transformed with wild type or mutated pGBKT7-PYLs into Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 cells. To detect protein interactions between RaptorB and SnRK2s, pGADT7 plasmids containing RaptorB were co-transformed with wild type or mutated pGBKT7-PYLs into Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 cells. Successfully transformed colonies were identified on yeast SD medium lacking Leu and Trp. Colonies were transferred to selective SD medium lacking Leu, Trp, His in the absence or presence of 10 μM ABA as indicated. To determine the intensity of protein interaction, saturated yeast cultures were diluted to 10−1, 10−2 and 10−3 and spotted onto selection medium. Photographs were taken after 4 days incubation at 30 °C.

Protoplast Isolation and Transactivation Assay

Protoplast isolation and transactivation assays were performed as previously described (Fujii et al., 2009). In brief, 4-week-old plants grown under a short photoperiod (10 hours light at 23°C/14 hours dark at 20°C) were used for protoplast isolation. Strips of young rosette leaves were treated with enzyme solution containing cellulase R10 (Yakult Pharmaceutical Industry) and macerozyme R10 (Yakult Pharmaceutical Industry) in the dark. After being diluted with equal volume of W5 solution (2 mM MES, pH 5.7, 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM KCl), the protoplasts were filtered through a nylon mesh and pelleted at 100 x g for 2 min. Protoplasts were resuspended in W5 solution and kept for 30 min. Protoplasts (100 μL) in MMg solution (4 mM MES, pH 5.7, 0.4 M mannitol, and 15 mM MgCl2) were mixed with the plasmid mix, and incubated for 5 min with 110 μL PEG solution (40% w/v PEG-4000, 0.2 M mannitol, and 100 mM CaCl2). The protoplasts were washed twice with 1 mL W5 solution. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated for 5 hours under light in washing and incubation solution (0.5 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7) with or without 5 μM ABA. All steps were performed at room temperature. The RD29B promoter fused to the LUC coding sequence was used as an ABA-responsive reporter gene (7 μg of plasmid per transfection). ZmUBQ::GUS was included in each sample as an internal control (1 μg per transfection). For ABF2-HA, SnRK2.6-FLAG, wild type and mutated PYLs and PP2C plasmids, 3 μg per transfection was used. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated for 5 hours under light in washing and incubation solution (0.5 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7) with or without 5 μM ABA.

To detect the effect of ABA and RaptorB overexpression on TOR kinase activity in protoplasts, protoplasts were co-transfected with constructs encoding S6K1 and other proteins (as indicated), incubated for 3 hours under light and then treated with 5 μM ABA for 2 hours before harvest.

Measurement of Chlorophyll Content

Seedlings were weighed, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground in liquid nitrogen, homogenized in extraction buffer (containing ethanol, acetone, and H2O in a ratio of 5:5:1), incubated at 37 °C for 4-h, and finally centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 645 nm and 663 nm using Wallac VICTOR2 plate reader (Perkin Elmer) with the 642 nm and 665 nm filters, respectively.

In-gel Kinase Assay

For in-gel kinase assays, 20 or 200 μg extract of total proteins was used for SDS/PAGE analysis with histone embedded in the gel matrix as the kinase substrate. After electrophoresis, the gel was washed three times at room temperature with washing buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated at 4 °C overnight with three changes of renaturing buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 5 mM NaF). The gel then was incubated at room temperature in 30 mL reaction buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EGTA, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM Na3VO4) with 200 nM ATP plus 50 mCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 90 min. The reaction was stopped by transferring the gel into 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 1% (w/v) sodium pyrophosphate. The gel was washed in the same solution for at least 5 hours with five changes fresh wash solution. Radioactivity was detected with a Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad). The radioactivity from each band was calculated by Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

In vitro Kinase Assays and Immunoprecipitation (IP) TOR Kinase Assays

1 μg wild type or mutated GST-PYL1 proteins were incubated with 0.005 μg GST-ABI1 with or without 5 μM ABA in 20 μL of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol), the reactions without PYL1 were used as control. After 15 minutes incubation, 1 μg MBP-SnRK2.6 was added to the reaction and incubated for additional 15 minutes. After the incubation step, a mixture containing 1 μM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 4 μg GST-ABF2 fragment, and phosphatase inhibit cocktail 3 was add to the reaction to total volume of 25 μL. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 minutes at 25 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding SDS sample buffer, and the mixtures were then subjected to SDS-PAGE. Radioactivity was detected with a Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad).

The immunoprecipitation kinase assays of TOR kinase were performed as previously described (Xiong et al., 2013). 10 μL immunoprecipitated TOR kinase was incubated with 1 μg recombinant PYLs proteins in 25 μL kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM cold ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, with or without 100 μM PP242 or 25 μM Torin 2) for 30 min at 25 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding of SDS sample buffer. After separation on 12% SDS-PAGE and subsequent gel drying, radiolabeled PYLs proteins were detected by the Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad). A parallel reaction using γ-[18O4]-ATP (Xue et al., 2014) and GST-PYL1 was subjected to trypsin digestion, phosphopeptides enriched, and LC-MS/MS analysis.

For detection of RaptorB phosphorylation by SnRK2.6, 1 μg GST-RaptorB-M proteins were incubated with 0.2 μg GST-SnRK2.6 in 20 μL of kinase buffer and 1 μM cold ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP for 60 min at 25 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding SDS sample buffer, and the mixtures were then subjected to SDS-PAGE. Radioactivity was detected with a Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad).

Co-Immunoprecipitation (CoIP) Assays

To detect the interaction between TOR and PYLs, 7-day old PYL1-Myc transgenic or WT seedlings from one 6-well plate were ground in liquid nitrogen and lysed in 1000 μL Co-IP buffer (400 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM pyrophosphate, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 0.3% CHAPS and 1× cocktail inhibitors [Roche]) for 1.5 hours at 4 °C. After centrifuging at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant of each sample was mixed with or without anti-TOR antibody and rotated at 4 °C for 2 hours and additional 2 hours after adding 15 μL pre-balanced protein G sepharose beads (GE healthcare). The immunoprecipitated proteins were washed three times with low salt wash buffer (400 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM pyrophosphate, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 0.3% CHAPS) before SDS-PAGE separation and protein blot analyses. To detect the interaction between TOR and RaptorB, 7-day old WT seedlings treated with or without 50μM ABA for 2 hours were used and anti-RaptorB antibody (Rabbit polyclonal antibody, Synthetic peptide sequence: c-HLEASRPSDPQPEP, Antigen affinity purified) were used for detection of RaptorB protein after immunoprecipitation.

To detect the phosphopeptide of PYL1 protein, 10-day old PYL1-Myc transgenic or WT seedlings were ground in liquid nitrogen and lysed in 1000 μL IP buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM aprotinin, 1 × Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Sigma], 0.1% Triton X-100). After centrifuging at 14,000g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant of each sample was mixed with anti-Myc antibody and rotated at 4 °C for 4 hours and additional 2 hours after adding 15 μL pre-balanced protein G Dynabeads (Thermofisher). The immunoprecipitated proteins were washed three times with wash buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM aprotinin, 1 × Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Sigma]) before digestion and phosphopeptide enrichment.

Protein Extraction and Digestion

Ground Arabidopsis tissues were lysed in 8 M urea in 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate. Proteins were reduced and alkylated with 10 mM tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine and 40 mM chloroacetamide at 37 °C for 30 min. Protein amount was quantified by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein extracts were diluted to 4 M urea and digested with Lys-C in a 1:100 (w/w) enzyme-to-protein ratio for 3 hours at 37 °C, and further diluted to a 1 M urea concentration. Trypsin was added to a final 1:100 (w/w) enzyme-to-protein ratio overnight. Digests were acidified with 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to a pH ~3, and desalted using a 100 mg of Sep-pak C18 column (Waters).

Phosphopeptide Enrichment

Phosphopeptide enrichment was performed according to the reported IMAC StageTip protocol with some modifications (Tsai et al., 2014). The in-house-constructed IMAC tip was made by capping the end with a 20 μm polypropylene frits disk (Agilent). The tip was packed with 5 mg of Ni-NTA silica resin by centrifugation at 200 × g for 1 min. Ni2+ ions were removed by 100 μL of 100 mM EDTA solution. The tip was then activated with 100 μL of 100 mM FeCl3 and equilibrated with 100 μL of loading buffer (6% (v/v) acetic acid at pH 3.0) prior to sample loading. Tryptic peptides (200 μg) were reconstituted in 100 μL of loading buffer and loaded onto the IMAC tip. After successive washes with 200 μL of washing buffer (4% (v/v) TFA, 25% acetonitrile (ACN)) and 100 μL of loading buffer respectively, the bound phosphopeptides were eluted with 150 μL of 200 mM NH4H2PO4. The eluted phosphopeptides from six IMAC StageTips were directly loaded on a C18 StageTip to perform high-pH reverse phase (Hp-RP) fractionation.

High-pH Reverse Phase StageTip Fractionation

High-pH Reverse Phase fractionation was performed with some modifications to a previous method (Dimayacyac-Esleta et al., 2015). 2 mg of the C18-AQ beads (5μm particles) were suspended in 100 μL of methanol and loaded into a 200 μL of StageTip with a 20 μm polypropylene frit. The C18 StageTips were activated with 100 μL of 40 mM NH4HCO2, pH 10, in 80% ACN, and equilibrated with 100 μL of 200 mM NH4HCO2, pH 10. After loading with eluted phosphopeptides from the IMAC StageTips, the C18 StageTips were washed with 100 μL of 200 mM NH4HCO2, pH 10. The bound phosphopeptides were fractionated from the StageTip with 50 μL of 8 different ACN concentrations: 4%, 7%, 10%, 13%, 16%, 19%, 22%, and 80% of ACN in 200 mM NH4HCO2, pH 10. The eluted phosphopeptides were dried and stored at −20 °C.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

The phosphopeptides were dissolved in 5 μL of 0.25% formic acid (FA) and injected into an Easy-nLC 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated on a 45 cm in-house packed column (360 μm OD × 75 μm ID) containing C18 resin (2.2 μm, 100Å, Michrom Bioresources). The mobile phase buffer consisted of 0.1% FA in ultra-pure water (Buffer A) with an eluting buffer of 0.1% FA in 80% ACN (Buffer B) run over a linear 60 min gradient of 6%–30% buffer B at flow rate of 250 nL/min. The Easy-nLC 1000 was coupled online with a Velos LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode in which a full-scan MS (from m/z 350–1500 with the resolution of 60,000 at m/z 400) was followed by top 10 collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS scans of the most abundant ions with dynamic exclusion for 60 s and exclusion list of 500. The normalized collision energy applied for CID was 35% for 10 ms activation time.

Proteomics Data Analysis

The raw files were searched directly against Arabidopsis Thaliana database (TAIR10) with no redundant entries using SEQUEST HT algorithm in Proteome Discoverer version 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and MaxQuant software (Cox and Mann, 2008). Peptide precursor mass tolerance was set at 15 ppm, and MS/MS tolerance was set at 0.6 Da. Search criteria included a static carbamidomethylation of cysteines (+57.0214 Da) and variable modifications of (1) oxidation (+15.9949 Da) on methionine residues, (2) acetylation (+42.011 Da) at N-terminus of protein, and (3) phosphorylation (+79.996 Da) on serine, threonine or tyrosine residues were searched. For 18O-phosphopeptides, heavy phosphorylation (+85.979 Da) was set as a variable modification. Search was performed with full tryptic digestion and allowed a maximum of two missed cleavages on the peptides analyzed from the sequence database. Relaxed and strict false discovery rates were set for 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. PhosphoRS (Taus et al., 2011) was utilized for localization of phosphorylation sites. Label-free quantitation was performed using Maxquant (version 1.5.0.28). All the mass spectrometric data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (Vizcaino et al., 2014) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD003746 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride).

ABA Binding Assay

The interaction between ABA and the recombinant SUMO-HIS tagged PYL1, PYL1S119A, PYL1S119D, PYL10, PYL10S88A, PYL10S88D, and PYL10S88E was measured by Thermal Stability Shift Assay (TSA) or Microscale Thermophoresis (MST). MST assays were performed as previously described (Parker and Newstead, 2014). Briefly, wild type and mutated PYL1 and PYL10 proteins were labeled in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl) using the Protein Labeling Kit RED-NHS (NanoTemper Technologies). ABA in a range of concentrations (0.0001 μM to 4 mM) was incubated with 2 μM of labeled proteins for 1 hour at 4 °C. The samples were then loaded into the NanoTemper glass capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies) and microthermophoresis was performed using 20 % LED power and 80 % MST. The KD values for ABA-PYLs binding were calculated using the mass action equation through the NanoTemper software (NanoTemper Technologies).

For the TSA assay, 5 μM of purified recombinant proteins were mixed with a range of concentration of ABA (0.4 μM to 6.25 mM), and then incubated with SYPRO Orange (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour on ice. All reactions were performed in final volumes of 10 μL in 384-well plates on a LightCycle 480II real-time PCR system (Roche). The mixtures were heated from 25 °C to 90 °C with a ramp rate of 0.06 °C/s, and fluorescence signals were recorded. Data were analyzed using the Protein Thermal Shift Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the melting temperature (Tm) values were calculated.

Phosphatase Activity Assay

For PYL1 and PYL4, phosphatase activity was measured using the colorimetric substrate pNPP (Sigma-Aldrich). Reactions were performed in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM Mg(OAc)2, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% BSA. ABA and PYLs were added as indicated. The concentrations of recombinant ABI1 and PYLs was 0.1 and 0.5 μM, respectively. Reactions were started by the addition of pNPP to a final concentration of 5 mM. The hydrolysis of pNPP was measured by reading the absorbance at 405 nm (A405).

For PYL10, the phosphatase activity assay used SnRK2.6 phosphopeptide (Fujii et al., 2009) as a substrate. The concentrations of recombinant HAB1, PYL10 and SnRK2.6 phosphopeptide were 0.1, 0.5 μM and 0.1 mM, respectively. Colorimetric dye (BioVision) was used to stop the reaction and to determine the released phosphate.

For measurement of the effect of TOR phosphorylation on PYL1 activity, 0.1 μM instead of 0.5 μM GST-PYL1 were used in the in vitro TOR kinase assay and subsequent phosphatase activity assay.

Alpha Screen Assay

Interactions between PYL10 and HAB1/ABI1 were assessed by luminescence-based AlphaScreen technology (Perkin Elmer) as previously described (Melcher et al., 2010). All reactions contained 100 nM recombinant H6-SUMO-PYL10 proteins bound to nickel-acceptor beads and 100 nM recombinant biotin-MBP-HAB1 or biotin-MBP-ABI1 bound to streptavidin-acceptor beads in the presence and absence of ABA.

RNA Extraction and Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from raptor1-2, es-tor transgenic seedlings treatment with estradiol, control seedlings with or without 3 hours rapamycin treatment (10 μM). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For real-time PCR assays, reactions were set up with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). A CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) was used to detect amplification levels (initial step at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 56 °C and 20 s at 72 °C). Quantification was performed using three independent biological replicates.

Electrolyte Leakage Assay

To measure ion leakage in seedlings induced by PEG treatment, 5-day-old wild type, raptor1-2 and estradiol treated es-tor seedlings were rinsed briefly in distilled water, and placed in a solution containing 30% PEG for 5 hours. After treatment, seedlings were rinsed briefly in distilled water and placed immediately in a tube with 5 mL of water. The tube was agitated gently for 3 hours before the electrolyte content was measured. Six replicates of each treatment were conducted.

Analysis of Microarray Data

GEO2R was used to identify differentially expressed genes between es-tor mutant and wild type requiring adjusted P-value < 0.01 and at least 2 fold changes. Data were deposited under accession number of GSE40245 (Xiong et al., 2013). Only data from experiments with glucose supplement were used in this analysis.

To identify stress responsive genes, we used three databases to obtain a list of genes responsive to salt, drought, osmotic and ABA stress: 1) The RIKEN Arabidopsis Genome Encyclopedia (RARGE) database; For RARGE database, we extracted genes that have a ≥ 2.5-fold expression change at any time course under different stresses (drought, NaCl, and ABA, and rehydration after dehydration 2 h). 2) Database Resource for the Analysis of Signal Transduction In Cells (DRASTIC). 3) Microarray data deposited in GEO datasets were used to identify stress responsive genes using GEO2R.

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Generation

To obtain different PYLs homologs in different species, proteins from a particular species were used as queries to blast against 14 PYLs. The proteins that can hit all 14 Arabidopsis PYLs (E value cutoff: 0.00001) were extracted. Proteins that have “specific” PYLs like domain use Batch CD-Search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) were retained as PYLs homologs. Multiple alignment results were generated using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). View of multiple aligned sequences and secondary structure using Espript interface (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript) (Gouet et al., 2003). The crystallographic structure of PYR1 (Protein databank code: 3K90) was taken. A phylogenetic tree of PYLs from 12 different plant species was generated using NCBI Taxonomy (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/CommonTree/wwwcmt.cgi).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Band intensity quantification of in-gel kinase assay results was performed using the Image Lab.

Statistical significance of relative luciferase activity, phosphatase activity, fresh weight, Rosetta diameter, relative intensity, ion leakage, gene expression was examined by Student’s t test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

All the mass spectrometric data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD003746 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride)

Raw image files are deposited on Mendeley Data (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/2zchtvbv58.1).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Phosphomimic mutations in PYLs abolish their activity in protoplasts and yeast, Related to Figure 1.

Figure S2. The Serine corresponding to Ser119 in PYL1 is evolutionarily conserved, Related to Figure 2.

Figure S3. Response of transgenic plants carrying wild type and phosphomimic mutated PYL1 to ABA treatment, Related to Figure 3.

Figure S4. The phosphorylation of PYLs by TOR kinase, Related to Figure 4.

Figure S5. Stress/ABA responsive genes are up-regulated in the es-tor line, Related to Figure 5.

Figure S6. SnRK2 interacts with and phosphorylates RaptorB, Related to Figure 6.

Table S1. Up- and down-regulated genes in es-tor, related to Figure 5.

Table S2. 1,043 abiotic stress-responsive genes that are up-regulated in es-tor, related to Figure 5.

Table S3. 246 ABA-responsive genes that are up-regulated in es-tor, related to Figure 5.

Table S4. Four genes encode components in ABA signaling or TORC are up-regulated in es-tor, related to Figure 5.

Table S5: Recombinant DNAs used in this study, related to STAR methods.

Table S6: Primers used in this study, related to STAR methods.

Highlights.

The TOR kinase phosphorylates ABA receptor PYLs at a conserved serine residue

PYLs phosphorylation inhibits stress responses by abolishing PYLs activities

Stress- and ABA-activated SnRK2s phosphorylate Raptor and inhibit TOR activity

TOR and ABA signaling balance plant growth and stress responses

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences including its Strategic Priority Research Program (Grant No. XDPB0404) and by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM059138 (to J.-K.Z), 5R41GM109626 and 1R01GM111788 (to W.A.T). We are grateful to Prof. Pedro Rodriguez of Universidad Politecnica de Valenci, Spain for kindly providing the pyr1pyl12458 mutant seeds, to Prof. Christian Meyer of Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin, France for kindly providing raptor mutants and to the National Centre for Protein Science Shanghai (Protein Expression and Purification system) for their instrument support and technical assistance. We would like to thank Life Science Editors for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

P.W., Y.X., and J.-K.Z. designed research. P.W., Y.Z., Z.L., C.-C.H., X.L., L.F., Y.J.H., Y.D., C.Z., J.G., M.C., X.H., and Y.Z. performed experiments; P.W., Y.Z., Z.L., C.C.H., S.X., K.T., X.W., W.T., Y.X., and J.K.Z. analyzed the results; P.W., Y.X., and J.K.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achard P, Cheng H, De Grauwe L, Decat J, Schoutteten H, Moritz T, Van Der Straeten D, Peng J, Harberd NP. Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science. 2006;311:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1118642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni R, Rodriguez L, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Pizzio GA, Rodriguez PL. News on ABA transport, protein degradation, and ABFs/WRKYs in ABA signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Jegla T. Guard cell sensory systems: recent insights on stomatal responses to light, abscisic acid, and CO2. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;33:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogre L, Henriques R, Magyar Z. TOR tour to auxin. EMBO J. 2013;32:1069–1071. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Liu J, Wang H, Yang C, Chen Y, Li Y, Pan S, Dong R, Tang G, Barajas-Lopez JdD, et al. GSK3-like kinases positively modulate abscisic acid signaling through phosphorylating subgroup III SnRK2s in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:9651–9656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316717111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C, Li Y, Leisse A, Zhang Y, Bartholomaeus L, Fernie AR, Willmitzer L, Giavalisco P. Systemic analysis of inducible target of rapamycin mutants reveal a general metabolic switch controlling growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2013;73:897–909. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere A, Cargnello M, Julien LA, Gao H, Bonneil E, Thibault P, Roux PP. Oncogenic MAPK signaling stimulates mTORC1 activity by promoting RSK-mediated raptor phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere A, Romeo Y, Acosta-Jaquez HA, Moreau J, Bonneil E, Thibault P, Fingar DC, Roux PP. ERK1/2 phosphorylate Raptor to promote Ras-dependent activation of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:567–577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater C, Peng K, Movahedi M, Dunn JA, Walker HJ, Liang YK, McLachlan DH, Casson S, Isner JC, Wilson I, et al. Elevated CO2-induced responses in stomata require ABA and ABA signaling. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2709–2716. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD. Brassinosteroid/abscisic acid antagonism in balancing growth and stress. Dev Cell. 2016;38:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL, Finkelstein RR, Abrams SR. Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;61:651–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I, Signora L, Beeckman T, Inze D, Foyer CH, Zhang H. An abscisic acid-sensitive checkpoint in lateral root development of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;33:543–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprost D, Truong HN, Robaglia C, Meyer C. An Arabidopsis homolog of RAPTOR/KOG1 is essential for early embryo development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimayacyac-Esleta BR, Tsai CF, Kitata RB, Lin PY, Choong WK, Lin TD, Wang YT, Weng SH, Yang PC, Arco SD, et al. Rapid high-pH reverse phase StageTip for sensitive small-scale membrane proteomic profiling. Anal Chem. 2015;87:12016–12023. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrenel T, Caldana C, Hanson J, Robaglia C, Vincentz M, Veit B, Meyer C. TOR signaling and nutrient sensing. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2016;67:261–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Dietrich D, Ng CH, Chan PM, Bhalerao R, Bennett MJ, Dinneny JR. Endodermal ABA signaling promotes lateral root quiescence during salt stress in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell. 2013;25:324–341. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.107227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Zhu JK. Arabidopsis mutant deficient in 3 abscisic acid-activated protein kinases reveals critical roles in growth, reproduction, and stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8380–8385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Chinnusamy V, Rodrigues A, Rubio S, Antoni R, Park SY, Cutler SR, Sheen J, Rodriguez PL, Zhu JK. In vitro reconstitution of an abscisic acid signalling pathway. Nature. 2009;462:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature08599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Verslues PE, Zhu JK. Identification of two protein kinases required for abscisic acid regulation of seed germination, root growth, and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:485–494. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Verslues PE, Zhu JK. Arabidopsis decuple mutant reveals the importance of SnRK2 kinases in osmotic stress responses in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1717–1722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018367108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D, Scherzer S, Mumm P, Stange A, Marten I, Bauer H, Ache P, Matschi S, Liese A, Al-Rasheid KAS, et al. Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinase-phosphatase pair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21425–21430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912021106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guzman M, Pizzio GA, Antoni R, Vera-Sirera F, Merilo E, Bassel GW, Fernández MA, Holdsworth MJ, Perez-Amador MA, Kollist H, et al. Arabidopsis PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors play a major role in quantitative regulation of stomatal aperture and transcriptional response to abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2483–2496. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]