The Human Microbiome Project and similar research has generated great interest in potential health benefits of microbiota transplantations (MTs). The use of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), the transfer of stool from a human donor to a human recipient, for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is considered by many to be standard-of-care therapy, and data on its safety and effectiveness are accumulating (1–3). Yet, although some physicians are practicing FMT using stool from donors known to the physician or patient, stool is inconsistently screened for infectious pathogens. The use of prescreened stool obtained from a stool bank and shipped to the physician is increasing, but the stool banks are not regulated. Patients who self-administer FMT using unscreened stool sourced from family or friends is also widely described. In consideration of these and other particular characteristics and challenges of MT, and the nascent regulatory landscape, we convened human microbiome researchers, legal experts, and others to explore regulatory pathways for MT (4). We believe our proposed approach is an improvement on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) current and proposed scheme and could provide a model for other countries that are contemplating regulatory frameworks for FMT.

With an estimated 625,000 cases per year in the United States and European Union (5, 6), CDI is an infection of the large intestine that causes inflammation, diarrhea, and sometimes death. Traditional therapy is antibiotics, but recurrence is common. Lack of bacterial diversity in the gut, often as a result of antibiotic use, promotes CDI but is restored through FMT, breaking the CDI recurrence cycle (7). Although FMT is receiving the most attention, other types of MT are emerging. “Vaginal seeding,” in which a newborn delivered by caesarean section (C-section) is swabbed over the skin, eyes, nose, and mouth by gauze that had been placed in the mother’s vagina, is being studied as a way to prevent allergies, asthma, obesity, and immune deficiencies more common in children delivered by C-section (8). MT involving the mouth, nares, and skin may not be far off.

The advent of these applications for MTs poses challenges for regulatory bodies. The transplanted material is not a “typical” drug, and thus may not be appropriate for the drug regulatory pathway. The material consists of a community of highly dynamic, metabolically active organisms (9). Many of the transferred organisms are challenging to culture in vitro, and it is difficult to test their effectiveness in animals (9). Each batch of “product” is different, making characterization of the transplanted material problematic.

Over the past 4 years, the FDA has struggled to regulate FMT, shifting its position several times. In May 2013, the FDA announced that it intended to regulate fecal material as a “biological product,” requiring an investigational new drug application (IND) and its attendant protocols for extensive clinical trials. In response to dissatisfaction among providers and patients, in July 2013, FDA stated that it would not enforce IND requirements for FMT used to treat CDI unresponsive to therapy, allowing physicians and stool banks to operate without an IND.

Most recently, in March 2016, the FDA published draft guidance (10) stating that it would require stool banks to submit an IND to obtain and distribute stool to physicians. The IND would not be enforced for physicians collecting and screening donor stool and performing the procedure, or for entities such as hospital laboratories that collect and prepare FMT products “solely under the direction of licensed health care providers” (10) for use by the provider’s patients. This would allow for a continuing supply of stool for patient treatment outside of obtaining stool from a known donor or stool bank.

By requiring stool banks to obtain an IND, the guidance appears to call for more research in the form of blinded, randomized clinical trials, moving away from the current FDA position that allows more widespread access to patients with CDI. The FDA may have also been responding to industry pressure from sponsors of competitor products that have obtained INDs and are engaged in costly clinical trials (11). Many potential consumers of FMT criticize the FDA guidance for creating barriers to access, and urged the FDA to continue to allow stool banks to provide FMT for treatment of CDI not responsive to standard therapies (12).

Many health care providers critical of the FDA draft guidance argue that stool banks provide a safe, rigorously tested product in a timely manner (12). They believe that many hospital and local laboratories, especially in rural areas, do not have facilities or training to conduct the same type of screening as stool banks, and are often unable to screen donors quickly. They point out that screening is expensive, not reimbursed by all payers, and hardest on poor patients (12). Several providers assert that fecal microbiota should be regulated as a tissue, not as a drug, critiquing an FDA decision that fecal matter is not human tissue (13, 14).

Our group evaluated alternatives to the drug regulatory paradigm, and elements of other regulatory frameworks including those for blood, human cells and tissues (15, 16), solid organs, and the “practice of medicine.” In evaluating alternatives, we considered whether a framework would ensure the safety and effectiveness of the transferred material, but also whether it would provide adequate information to patients about benefits and risks, ensure access for patients who need the procedure, encourage research and development of microbiota-based therapies, and support public health objectives to reduce the burden of antibiotic resistance. The group also reviewed FMT regulatory frameworks from other countries, ranging from unregulated at the national level (e.g., Ireland, Australia), to only available as a drug via a clinical trial, or from a donor known to the patient or provider (e.g., France, Germany, Canada). Because of its stringent regulatory environment, some patients are leaving the United States to seek FMT for a range of conditions other than CDI (17).

There was clear support among the majority of working group members for a three-track regulatory scheme (see text box and table S1). This framework has parallels to the FDA’s 2016 draft guidance, but also distinct advantages over the current and proposed FDA scheme. We attempt to provide continued access for patients and more data on safety and effectiveness for regulators and providers, while requiring research on applications of FMT other than CDI. Because the FDA’s proposed framework requires physicians obtaining stool from stool banks to participate in a clinical trial under an IND, some patients may not be eligible to participate in the trial, or may not go to a trained provider out of concern that they will receive a placebo. Instead, they may do the procedure themselves, enlisting a relative or friend to donate stool. This increases risk of transmission of infectious diseases, as the donor may not be appropriately screened. Some patients may continue to take less-effective antibiotics, which promotes antibiotic resistance, and continue to suffer from the disease.

Our proposal improves on the FDA’s current and proposed regulatory scheme as it allows stool banks to continue to provide stool but only under an approved regulatory framework. Currently, stool banks are not regulated. Under the proposed FDA guidance, stool banks would be nonexistent or would have to operate under an IND. By requiring that stool banks report to a registry, the proposal will allow for ongoing capture of patient outcome data on safety and effectiveness. Although data would be collected under the proposed IND requirement, there are no requirements for such data collection under FDA’s current enforcement discretion policy.

Our proposed framework has a potential downside. Allowing stool banks to continue to provide stool to physicians for treatment of CDI, even after a new drug is approved for that indication, may discourage investment in track 3 drugs to treat CDI and other conditions that could be treated by stool-based products. This assumes that patients would prefer an FMT to a more traditional FDA-approved treatment. We do not know whether this assumption is correct. Cost and insurance coverage are likely to play a role in that decision.

The proposed framework would be relatively easy to implement. FDA would need to change its position and determine that microbiota derived from stool is a tissue, not a drug or biological product (13). The framework could be implemented through new guidance or by issuing formal regulations (18, 19), and no statutory changes would be required. The scheme would serve as a useful starting point for regulation of other types of MT.

Supplementary Material

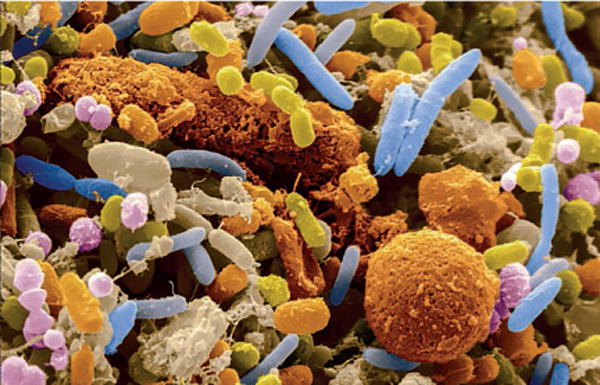

Scanning electron micrograph of human feces shows that a large proportion of feces is bacteria.

Proposed three-track regulatory scheme.

Track 1

When performed by a physician with stool acquired from someone known to the physician or to the patient, FMT would be regulated as the “practice of medicine” subject primarily to state regulation. Physicians performing FMT for CDI would be able to do so based on their scope of practice using clinical judgment and the relevant standard of care (20). An IND would be required for indications other than CDI unless the use meets the legal requirements for “clinical innovation,” i.e., the patient has not responded to conventional treatments and has a terminal or life-threatening medical condition (20).

Track 2

Stool could be obtained for FMT from stool banks that would be regulated in the same manner as human cell–tissue establishments with some additional oversight (21). This would include registering annually with the FDA and complying with rules for donor screening and testing and “good manufacturing practices” (21). Donor screening and testing would include a medical history and physical examination to exclude those with diseases linked to the gastrointestinal microbiota and tests for all relevant communicable diseases. Stool banks would be required to have their physician users report adverse events and data on outcomes to the stool bank. The stool bank, in turn, would be required to submit safety data to the FDA, and safety and outcomes data to a national registry (22). Unless operating under an IND, stool banks would only be able to provide fecal material for physicians using it to treat CDI not responding to standard therapy.

Track 3

This applies to “modified stool-based products,” i.e., stool processed in such a way that the original relevant characteristics of the transferred community of microorganisms have been altered. For example, this would include bacteria cultured from stool and assembled as a defined microbial population or a specific microbial consortium resulting from directly processing stool. These products would be regulated as biological products or drugs with some alteration of IND requirements (e.g., elimination of some phase I IND requirements and modification of characterization specifications).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21AI119633). The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors. The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of the members of the working group (4).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cammarota G, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835. doi: 10.1111/apt.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly CR, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:609. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.www.law.umaryland.edu/programs/health/events/microbiota/

- 5.Lessa FC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbut F, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Europe: A CDI Europe report. 2013 www.multivu.com/assets/60637/documents/60637-CDI-HCP-Report-original.pdf.

- 7.Song Y, et al. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e81330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: Vaginal seeding. www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Vaginal-Seeding.

- 9.Petrof EO, Khoruts A. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Enforcement policy regarding investigational new drug requirements for use of fecal microbiota for transplantation to treat Clostridium difficile infection not responsive to standard therapies. Draft guidance for industry. 2016 Mar; www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Vaccines/UCM488223.pdf?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

- 11.Rebiotix. Comment on FDA–2013–D–0811. 2016 Jun 20; www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2013-D-0811-0116.

- 12.Comments on FDA-2013-D-0811. www.regulations.gov/docketBrowser?rpp=50&so=DESC&sb=postedDate&po=0&dct=PS&D=FDA-2013-D-0811.

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Tissue Reference Group: FY 2012 Update. 2012 www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/tissuetissueproducts/regulationoftissues/ucm152857.htm.

- 14.Khoruts A. Comment on FDA–2013–D–0811. 2016 Apr 25; www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2013-D-0811-0065.

- 15.Smith MB, Kelly C, Alm EJ. Nature. 2014;506:290. doi: 10.1038/506290a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachs RE, Edelstein CA. J Law Biosci. 2015;2:396. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsv032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Written comments from working group member Catherine Duff, Founder and President of the Fecal Transplant Foundation. submitted December 2016; www.law.umaryland.edu/programs/health/events/microbiota/documents/wg3/CatherineDuffComments.pdf.

- 18.Sachs RE, Edelstein CA. J Law Biosci. 2015;2:396. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsv032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riley MF, Olle B. J Law Biosci. 2015;2:742. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsv046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laakmann AB. Cardozo Law Rev. 2015;36:913. [Google Scholar]

- 21.21 CFR 1271, subparts A–F

- 22.American Gastroenterological Association. FMT National Registry. www.gastro.org/patient-care/registries-studies/fmt-registry.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.