Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Diagnosis of bacterial meningitis often requires cytometry, chemistry and/or microbiologic culture capabilities. Unfortunately, laboratory resources in low-resource settings (LRS) often lack the capacity to perform these studies. We sought to determine whether the presence of white blood cells in CSF detected by commercially available urine reagent strips could aid in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis.

METHODS

We searched PubMed for studies published between 1980 and 2016 that investigated the use of urine reagent strips to identify cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis. We assessed studies in any language that enrolled subjects who underwent lumbar puncture and had cerebrospinal fluid testing by both standard laboratory assays and urine reagent strips. We abstracted true-positive, false-negative, false-positive and true-negative counts for each study using a diagnostic threshold of ≥10 white blood cells per microlitre for suspected bacterial meningitis and performed mixed regression modelling with random effects to estimate pooled diagnostic accuracy across studies.

RESULTS

Our search returned 13 studies including 2235 participants. Urine reagent strips detected CSF pleocytosis with a pooled sensitivity of 92% (95% CI: 84–96), a pooled specificity of 98% (95% CI: 94–99) and a negative predictive value of 99% when the bacterial meningitis prevalence is 10%.

CONCLUSIONS

Urine reagent strips could provide a rapid and accurate tool to detect CSF pleocytosis, which, if negative, can be used to exclude diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in settings without laboratory infrastructure. Further investigation of the diagnostic value of using protein, glucose and bacteria components of these strips is warranted.

Keywords: urine reagent strip, meningitis, cerebrospinal fluid, reagent strip, urine test strip

Introduction

Bacterial meningitis is among the top ten contributors to mortality in children under 5 years of age worldwide, accounting for 2–3% of deaths in this age group [1, 2]. Adults are affected as well, with more than a million reported cases of bacterial meningitis in the Africa meningitis belt over the last 20 years [3]. The mortality rate due to bacterial meningitis is greater than 50% in selected populations, including HIV-infected individuals [4]. Morbidity is also high, with 20% of survivors demonstrating permanent sequelae, such as hearing loss, neurologic disability or loss of limb [5]. Fortunately, morbidity can be mitigated through prompt identification and treatment [6].

The diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is supported by an elevated opening pressure, the appearance of cloudy cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a decreased CSF glucose concentration, an increased CSF protein concentration, positive CSF bacterial cultures and CSF pleocytosis (elevated white blood cells [WBC], defined by WBC ≥10 per microlitre [WBC/μL]) [6–8]. In areas with adequate microbiologic laboratory infrastructure, a combination of gram staining and cultures of CSF is often relied upon as the gold standard for diagnosis. However, in low-resource settings (LRS), cytology, chemistry and reliable microbiologic laboratory analyses are often unavailable [9]. Practitioners in these settings often rely on clinical examination coupled with subjective assessments, such as evaluating the general appearance of the CSF, which have poor diagnostic yield [10–12].

Consequently, there is a need for affordable, rapid and accurate methods to aid in diagnosing bacterial meningitis in LRS. Urine reagent strips, which are designed to diagnose urinary tract infections, are theoretically able to test for several components in CSF that are potentially valuable for diagnosing meningitis, including protein, glucose, white blood cells and red blood cells. Over the last 30 years, several studies have investigated the use of urine reagent strips as a means to aid in the diagnosis of meningitis. We conducted a meta-analysis of the published literature to assess the utility of the leucocyte esterase assay on urine reagent strips to accurately detect the presence of white blood cells in CSF. We aimed to assess whether urine reagent strips have adequate diagnostic validity to suggest bacterial meningitis for use in LRS without laboratory infrastructure requisite for standard meningitis diagnostics.

Methods

Data sources

We searched PubMed for studies published in any language before September 2016 that examined the use of urine reagent strips as an aid in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Our searches included the following index terms: reagent strip, urine reagent strip, stix, urine test strip, cerebrospinal fluid and meningitis (See Appendix S1 and S2). We also reviewed reference lists published in retrieved studies and review articles to add any relevant articles not discovered by our search.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Study inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) a lumbar puncture to obtain CSF; (ii) either a CSF cell count or microbiologic test for bacterial meningitis was performed; and (iii) a urine reagent strip was used to test the CSF and determine the presence of WBC. Studies were excluded if the urine reagent strip is no longer manufactured. A single reviewer (WB) reviewed all abstracts for inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

We abstracted the number of true-positive, false-negative, false-positive and true-negative cases from each included study. A true-positive case was defined as when the leucocyte esterase assay of a urine reagent strip showed a positive change on a CSF specimen with ≥10 WBC/μL. When WBC/μL were not reported, a true-positive case was defined when a CSF culture was positive for bacteria, except in the case of a single study (Molyneux et al.) for which all confirmed aetiologies of meningitis were considered as a positive result (i.e. tuberculosis, viral or bacterial). A true-negative case was defined as when the leucocyte esterase assay of a urine reagent strip was negative for a CSF specimen with <10 WBC/μL. For each study, we also abstracted: (i) the country where the study was conducted; (ii) the number of patients in each study; (iii) the year the study was published; (iv) the brand and name of the urine reagent strip analysed; and (v) the age ranges of the subjects.

Data quality assessment

For each study, we analysed the quality of the study design and potential for bias. Quality categories involved inclusion/exclusion criteria, number of observers interpreting the urine reagent strips, whether the observers were blinded, and attention to inter- and/or intra-observer bias.

Statistical analysis

Using abstracted data for true positives, true negatives, false positives and false negatives from each study, we fit bivariate mixed effects logistic regression models to estimate pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and 95% confidence intervals for each measure [10], and graphically summarised the data with a forest plot. We estimated study heterogeneity with inconsistency-squared (I2) and assessed for publication bias by regressing the log odds ratio of each study on the inverse root of the sample size (Deek’s plot) and estimating the linear coefficient. We repeated our analysis with a sample restricted to the seven studies using Combur urine reagent strips. Finally, we calculated positive and negative predictive values across a range of estimated prevalence of bacterial meningitis among suspected cases. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata Version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study selection

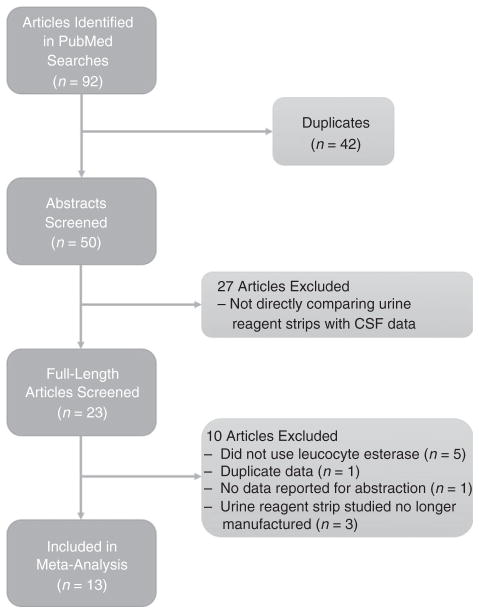

Ninety-two studies were identified by the initial searches, which contained 42 duplicates. After a review of the abstracts, 37 studies were rejected due to insufficient data or lack of a direct comparison between urine reagent strips and laboratory and/or microbiological data (Figure 1). Reasons for rejecting specific articles are listed in the supplement (See Appendix S1 and S2). A total of 13 articles including 2235 total study participants were ultimately included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart.

Study characteristics

A plurality of studies was conducted in India (5/13), with two in Germany, two in Spain and one each in the USA, Kuwait, Malawi and Portugal. Studies ranged in sample size from 36 to 942. Nine studies evaluated the Combur9 or Combur10 urine reagent strips, three studies analysed the Bayer Multistix and one study analysed the Chemstrip LN. Characteristics of the studies are collated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of articles and population included in meta-analysis to estimate sensitivity and specificity of leucocyte esterase assays to detect pleocytosis

| Study No. | Authors | Country of study | Patients (n) | Age range (years) | Year of study | Urine reagent strip used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bisharda et al. [24] | India | 36 | N/A | 1999 | Multistix 8SG |

| 2 | López Paredes et al. [16] | Spain | 62 | N/A | 1988 | Multistix 10SG |

| 3 | Molyneux et al. [23] | Malawi | 257 | N/A | 1996 | Multistix 8SG |

| 4 | DeLozier et al. [13] | USA | 942 | N/A | 1989 | Chemstrip LN |

| 5 | Parmar et al. [26] | India | 63 | 1–5 | 2004 | Combur10 |

| 6 | Salvador et al. [22] | Spain | 68 | N/A | 1988 | Combur9 |

| 7 | Kumar et al. [27] | India | 75 | 0.25–12 | 2014 | Combur10 |

| 8 | Joshi et al. [14] | India | 75 | 0–75 | 2013 | Combur10 |

| 9 | Heckmann et al. [20] | Germany | 75 | N/A | 1996 | Combur9 |

| 10 | Hastka et al. [21] | Germany | 92 | N/A | 1992 | Combur9 |

| 11 | Chikkannaiah et al. [15] | India | 103 | 0–75 | 2016 | Combur10 |

| 12 | Romanelli et al. [25] | Portugal | 154 | 0.08–12 | 2001 | Combur10 |

| 13 | Moosa et al. [17] | Kuwait | 234 | N/A | 1995 | Combur9 |

Risk of bias within studies

The majority of the studies included subjects with suspected bacterial meningitis. In contrast, four studies, DeLozier et al. [13], Joshi et al. [14], Chikkannaiah et al. [15] and López Paredes et al. [16] included subjects who had received a lumbar puncture for any indication. These four studies correlated WBC/μL with the leucocyte esterase assay on the urine reagent strip in the absence of other laboratory or clinical data. None of the studies investigated or mentioned inter- or intraobserver bias.

Synthesis of results

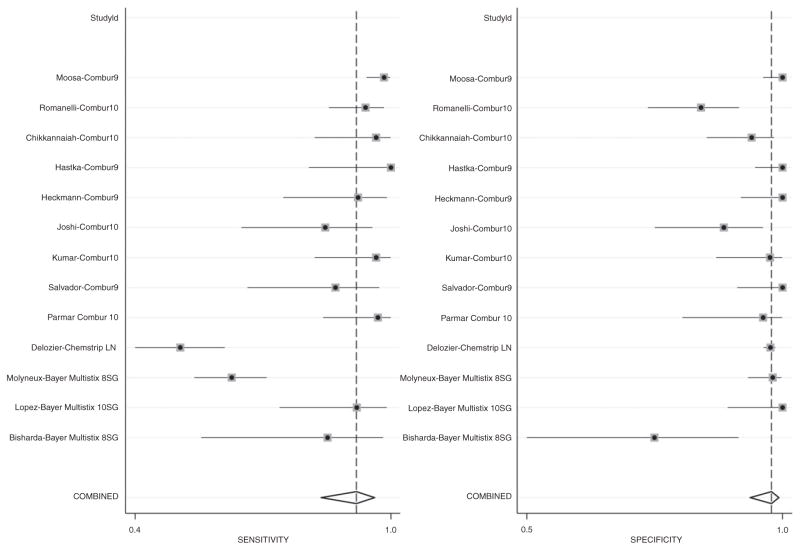

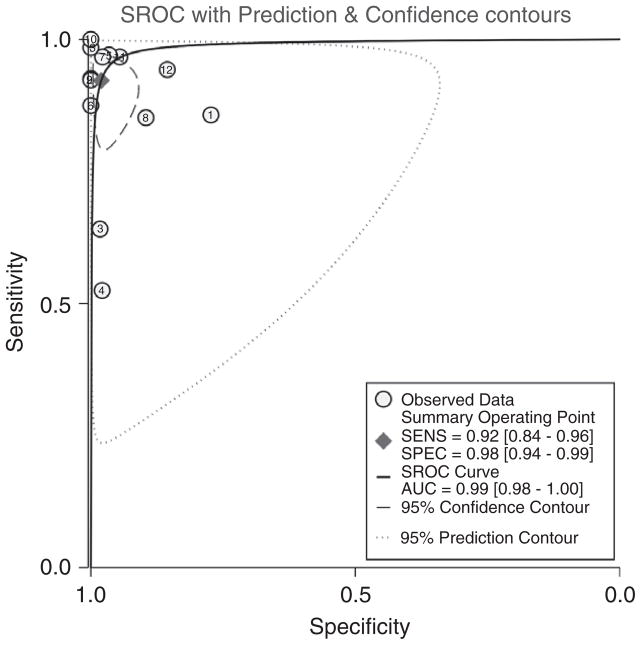

The pooled sensitivity and specificity for all studies using urine reagent strips to identify pleocytosis were 92% (95% CI: 84–96) and 98% (95% CI: 94–99), respectively (Table 3). The pooled positive and negative likelihood ratios were 46.9 and 0.08, respectively. The study by DeLozier et al. [13] was the only one evaluating the Chemstrip LN, which had a sensitivity and specificity of 52% [95% CI: 42–63] and 98% [95% CI: 97–99], respectively. The sensitivities and specificities were marginally higher when we performed analyses on only the studies that used Combur strips (96% [95% CI: 92–97] and 98% [95% CI: 93–100], respectively). The pooled sensitivities and specificities are graphically displayed in the forest plot in Figure 2 and are depicted as a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Performance of Multistix and Combur urine reagent strips*

| Study No. | Authors | Strip | Sen (95% CI) | Spe (95% CI) | PLR | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bisharda et al. [1] | Multistix 8SG | 86% (57–98) | 77% (55–92) | 28.1 (4–193) | 0.03 (0–0.21) |

| 2 | López Paredes et al. [2] | Multistix 10SG | 92% (75–99) | 100% (90–100) | 67.2 (4–1056) | 0.09 (0.03–0.31) |

| 3 | Molyneux et al. [3] | Multistix 8SG | 64% (56–72) | 98% (94–100) | 36.9 (9–146) | 0.37 (0.29–0.46) |

| 4 | DeLozier et al. [4] | Chemstrip LN | 52% (42–63) | 98% (97–99) | 24.5 (15–40) | 0.49 (0.40–0.60) |

| 5 | Parmar et al. [5] | Combur10 | 97% (85–100) | 96% (82–100) | 28.2 (4–193) | 0.03 (0–0.21) |

| 6 | Salvador et al. [6] | Combur9 | 87% (68–97) | 100% (92–100) | 77.4 (5–1224) | 0.14 (0.05–0.37) |

| 7 | Kumar et al. [7] | Combur10 | 96% (83–100) | 97% (88–100) | 43.5 (6–302) | 0.03 (0–0.23) |

| 8 | Joshi et al. [8] | Combur10 | 85% (66–96) | 89% (77–97) | 8.2 (4–19) | 0.17 (0.07–0.41) |

| 9 | Heckmann et al. [9] | Combur9 | 93% (76–99) | 100% (93–100) | 89.2 (5.6–1410) | 0.09 (0.03–0.29) |

| 10 | Hastka et al. [10] | Combur9 | 100% (81–100) | 100% (95–100) | 146 (9–2315) | 0.03 (0–0.41) |

| 11 | Chikkannaiah et al. [11]. | Combur10 | 96.7% (83–100) | 94.5% (87–98) | 17.6 (7–46) | 0.04 (0.01–0.24) |

| 12 | Romanelli et al. [12] | Combur10 | 94.3% (86–98) | 85.5% (76–92) | 6.5 (4–11) | 0.07 (0.03–0.17) |

| 13 | Moosa et al. [13] | Combur9 | 98.4% (95–100) | 100.0% (97–100) | 207.9 (13–3302) | 0.02 (0.01–0.07) |

| Pooled Estimate All Studies | N/A | 92% (84–96) I2: 95.1% (93–97) |

98% (94–99) I2: 95.3% (94–97) |

46.9 (16–141) I2: 91.2% (91–96) |

0.08 (0.04–0.17) I2: 96.2% (95–97) |

|

| Pooled Estimate Combur Only | N/A | 96% (92–97) I2: 58.9% (29–89) |

98% (93–100) I2: 85.0% (76–94) |

55.3 (13–232) I2: 73.4% (73–93) |

0.05 (0.03–0.08) I2: 64.1% (38–90) |

Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; CI, confidence interval; I2, inconsistency–squared.

The superscript in the ‘Authors’ column denotes the analyses that are detailed in Appendix S1.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity and specificity forest plot.

Figure 3.

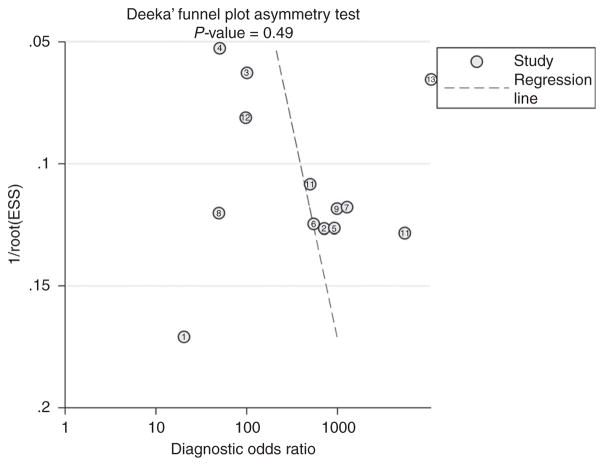

Funnel Plot. Studies are identified by the study numbers used in Tables 1–3.

We estimated the positive and negative predictive values based on pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity calculated across a range of prevalence rates of bacterial meningitis among suspected cases. In the thirteen studies examined, the prevalence of bacterial meningitis in the CSF examined ranged from 11% to 55%. Assuming a prevalence of bacterial meningitis of 10% among subjects who receive a lumbar puncture, the PPV and NPV of the urine reagent strips are 84% and 99%, respectively (Table 4). The results for a prevalence of 10%, 50% and 90% are also displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Calculated PPV and NPV by prevalence of CSF pleocytosis among suspected cases*

| Population Prevalence | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 84% | 99% |

| 50% | 98% | 92% |

| 90% | 100% | 58% |

PPV and NPV were calculated using the 92% and 98% sensitivity and specificity, respectively, of all studied urine reagent strips in identifying CSF pleocytosis.

I2 ranged from 58.9% to 96.2% for the calculated sensitivities, specificities and likelihood ratio, implying moderate to considerable heterogeneity between the studies. Lastly, we assessed for publication bias using a Deek’s Funnel Plot Asymmetry Test (Figure 4). Despite the fair amount of heterogeneity in the studies, the high P-value (0.49) and the visual inverse-funnel shape in Figure 4 overall mitigates concern for major publication bias. One study by Moosa et al. [17] was noted to be an outlier on the funnel plot.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Studies are identified by the study numbers used in Tables 1–3.

Discussion

In a meta-analysis of published data on the diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick leucocyte esterase assay for detection of CSF pleocytosis, we found a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 98%, respectively. These results correspond to relatively high positive and negative predictive values (>92%) in settings with moderate to high rates (50%) of bacterial meningitis among suspected cases. In scenarios where the pre-test probability of bacterial meningitis is low (e.g. <10%), the test may serve as an effective means of excluding significant meningitis (NPV = 99%), including most forms of bacterial meningitis, which carries high rates of morbidity and mortality (4).

In LRS, there are few efficient, affordable and accurate approaches to detect bacterial meningitis. As a result, clinicians often empirically treat patients with fever and altered mental status for suspected bacterial meningitis without the support of laboratory-based data [9]. An accurate and inexpensive point-of-care (POC) test may empower providers to diagnose and treat bacterial meningitis. Drain et al. performed a review of studies using POC testing in LRS and proposed revised criteria for an ideal diagnostic POC test, including: (i) affordability, (ii) rapidity, (iii) ease of use, (iv) ease of interpretation, (v) high sensitivity (few false negatives) and (vi) high specificity (few false positives) [18]. Urine reagent strips are inexpensive, easy to use and interpret, and generate results within seconds to minutes. For suspected bacterial meningitis, a POC test with high sensitivity is arguably preferable to one with high specificity, because it will enable practitioners to ensure patients are not left untreated for a life-threatening condition. We calculated pooled sensitivity and specificity of the Combur urine reagent strips to be approximately 96% and 98%, respectively, corresponding to strong but not exceptional testing accuracy for identification of CSF pleocytosis.

Our results demonstrate an important advance in the literature on urine dipstick for diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, which previously demonstrated less valid estimates. Whereas Smalley et al. [19] first reported on the use of the leucocyte esterase assay to diagnose three cases of bacterial meningitis, their sample size and use of Chemstrip-L urine reagent strips, which are no longer manufactured, limit its import. Data published in the interim have demonstrated contrasting results. Heckmann et al. [20], Hastka et al. [21], Salvador et al. [22] and Moosa et al. [17] examined the accuracy of the Combur9 urine reagent strips with promising results. In contrast, DeLozier et al. [13] found that the Chemstrip LN leucocyte esterase assay demonstrated poor sensitivity to detect white blood cells. Following that study, Molyneux and Walsh [23] reported poor performance of the Bayer Multistix 8SG, with a sensitivity of 33% and a specificity of 83% when testing clear CSF, but near-perfect accuracy when testing cloudy CSF. They concluded that urine strips were not likely to add meaning beyond inspection for fluid turbidity. This study was corroborated by Bisharda et al. [24], who also used Bayer Multistix 8SG. A subsequent review in 1997 by Bonev et al. concluded that using urine strips to detect CSF pleocytosis was not of diagnostic value [11].

However, the historically poor sensitivity of urine reagent strips can be attributed to studies involving now outdated urine reagent strips. More recent studies by Romanelli et al. [25], Parmar et al. [26] and Kumar et al. [27] revisited the utility of urine reagent strips when using the newer Combur10 test strips, reporting much higher sensitivities and specificities. In our review of the literature, which is largely comprised of these newer assays, we conclude that the reagent strips hold promise as a diagnostic tool in LRS and may be used to better inform clinicians about therapeutic considerations for suspected bacterial meningitis when further diagnostic testing is not readily available.

Notably, we did identify a fair amount of heterogeneity between the studies. We attribute this to studies by Molyneux and Bisharda [23, 24], which used the Bayer Multistix 8SG urine reagent strips. For example, the calculated sensitivity to detect the presence of WBC was 64.1% in the study by Molyneux et al. [23], whereas the ranges of sensitivity and specificity were 85–100% and 90–100%, respectively, in the studies that investigated the other test strip brands. Furthermore, the calculated specificity was 77.3% in the study by Bisharda et al. [24], whereas it was at least above 89% in all the other studies. Importantly, newer versions of the Bayer Multistix performed better. The study by López Paredes et al. [16] in 1988 evaluated the Bayer Multistix 10SG found excellent sensitivity and specificity with the leucocyte esterase assay in both cerebrospinal fluid and seminal and peritoneal fluids. Despite the heterogeneity, overall, we found relatively high sensitivity and specificity in use of urine reagent strips to identify pleocytosis.

There are several limitations to be noted in this study. First, we did not differentiate between viral, bacterial and tuberculosis meningitides. Diagnosing these conditions requires specific cultures and assays. Furthermore, although specific protein and glucose values can be supportive of these conditions, we did not investigate the diagnostic validity of urine reagent strips and their protein and glucose assays when testing CSF. Similarly, when the gold standard of culture-positive bacterial meningitis was lacking, we used a cut-off of ≥10 WBC/μL as a surrogate for suspected bacterial meningitis. As such, our findings are generalisable to the diagnosis of CSF pleocytosis and therefore possibly bacterial meningitis, but are not cause specific. Second, our review of the literature only evaluated leucocyte esterase assay detection by urine reagent strips, microscopic enumeration of white blood cells from CSF and intermittent microbiological culture data. We did not assess the diagnostic accuracy of assays that detect blood, protein, glucose, bacteria or nitrite commonly found on urine reagent strips. Several papers suggest that these modalities may have utility in further assessing CSF, including identifying and differentiating between causes of meningitis [14, 15, 17, 22, 25–31]. Future studies should examine relationships between the above-mentioned values and standard CSF diagnostics to better consider the full value of urine reagent steps as diagnostic tools for bacterial meningitis. Finally, the studies examined had relatively small sample sizes as evidenced by the wide confidence intervals in our pooled estimates, and not all studies utilised the newest urine reagent strips (e.g. Combur10 and Bayer Multistix 10SG). Larger studies with newer urine reagent strips might help further this line of investigation.

Conclusions

This review summarises the diagnostic accuracy of urine reagent strips to detect CSF pleocytosis. Although standard laboratory evaluation practices clearly remain the gold standard, urine reagent strips have relatively high sensitivity and specificity, and might hold diagnostic value in settings where standard laboratory tests are unavailable. The Combur10 strips appear to be the most promising of those evaluated to date. They could be considered as a rule-out test to prevent unnecessary use of antibiotics and promote further diagnostic evaluation in certain scenarios. Because urine reagent strips cannot differentiate between aetiologies of meningitis, further assays or cultures should be used for this purpose when the leucocyte esterase assay is positive. Future studies should evaluate newer versions of reagent strips in LRS and consider other elements of the strips (e.g. glucose, protein, bacteria) to aid in the diagnostic utility in settings where advanced laboratory testing is not available.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Detailed approaches to assessing data from the included studies.

Appendix S2. Listed below are the studies obtained on PubMed.

Table 1.

Assessment of study quality summarising the inclusion and exclusion criteria, whether the studies were blinded, and the number of observers

| Study No. | Authors | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Diagnostic reference standard for bacterial meningitis | Observers blinded? | Number of observers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bisharda et al. [24] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | CSF Culture | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | López Paredes et al. [16] | N/A | N/A | Did not test for bacterial components | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Molyneux et al. [23] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | CSF culture | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | DeLozier et al. [13] | All CSF samples received in laboratory over 5 months | N/A | CSF culture | Yes | 2 |

| 5 | Parmar et al. [26] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | Pleocytosis/CSF findings* or CSF culture when available | Yes | 1 |

| 6 | Salvador et al. [22] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | Pleocytosis/CSF findings* or CSF culture when available | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | Kumar et al. [27] | Suspected meningitis | Children <0.25 years, contraindication to LP, shunt-related infections, and no consent obtained | Pleocytosis/CSF findings* or CSF culture when available | Yes | 1 |

| 8 | Joshi et al. [14] | All CSF samples received in laboratory over 2 months | Insufficient quantity of CSF | Did not test for bacterial components | Yes | 1 |

| 9 | Heckmann et al. [20] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | Pleocytosis, cultures not specified | N/A | N/A |

| 10 | Hastka et al. [21] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | Pleocytosis, cultures not specified | N/A | N/A |

| 11 | Chikkannaiah et al. [15] | All CSF samples received in laboratory over 4 months | Haemorrhagic CSF samples | Did not test for bacterial components | Yes | 1 |

| 12 | Romanelli et al. [25] | Suspected meningitis | Non-infectious aetiology | Pleocytosis/CSF findings* or CSF culture when available | N/A | N/A |

| 13 | Moosa et al. [17] | Suspected meningitis | N/A | Pleocytosis/CSF findings* or CSF culture when available | N/A | N/A |

CSF Findings refer to quantification of protein, glucose and red blood cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues from the Massachusetts General Hospital, Phoebe Yager and Maureen Clark, for logistic assistance. MJS receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (MH K23099916).

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- 1.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diarrhea management in children under five in sub-Saharan Africa: does the source of care matter? – UNICEF DATA [Internet] [12 Dec 2016];UNICEF DATA. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3475-1. (Available from: http://data.unicef.org/child-survival/under-five.html) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.WHO. Number of suspected meningitis cases and deaths reported [Internet] [12 Dec 2016];Who.int. 2016 Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/epidemic_diseases/meningitis/suspected_cases_deaths_text/en/

- 4.Kelly M, Benjamin L, Cartwright K, et al. Epstein-Barr virus coinfection in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with increased mortality in Malawian adults with bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2011;205:106–110. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapter 2: Epidemiology of Meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza. [Internet] CDC; 2016. [19 July 2016]. [cited 12 December 2016]. (Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/meningitis/lab-manual/chpt02-epi.html) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tunkel A, Hartman B, Kaplan S, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1267–1284. doi: 10.1086/425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigrovic L. Clinical prediction rule for identifying children with cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis at very low risk of bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2007;297:52. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byington C, Kendrick J, Sheng X. Normative cerebrospinal fluid profiles in febrile infants. J Pediatr. 2011;158:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petti C, Polage C, Quinn T, Ronald A, Sande M. Laboratory medicine in Africa: a barrier to effective health care. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:377–382. doi: 10.1086/499363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molyneux E. Where there is no laboratory, a urine patch test helps diagnose meningitis. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4:117. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.112729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonev V, Gledhill R. Use of reagent strips to diagnose bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 1997;349:287–288. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)64902-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitsma J, Glas A, Rutjes A, Scholten R, Bossuyt P, Zwinderman A. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLozier J, Auerbach P. The leukocyte esterase test for detection of cerebrospinal fluid leukocytosis and bacterial meningitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi D, Kundana K, Puranik A, Joshi R. Diagnostic accuracy of urinary reagent strip to determine cerebrospinal fluid chemistry and cellularity. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4:140. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.112737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chikkannaiah P, Benachinmardi K, Srinivasamurthy V. Semi-quantitative analysis of cerebrospinal fluid chemistry and cellularity using urinary reagent strip: an aid to rapid diagnosis of meningitis. Neurology India. 2016;64:50. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.173641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López Paredes A, Valera Mortón C, Ródenas García V, Pedromingo Marino A, Martínez Hernández P. The leukocyte zone on Multistix-10-SG reactive strips for cerebrospinal, seminal and peritoneal fluids. Med Clin (Barc) 1988;90:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moosa A, Ibrahim M, Quortum H. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis with reagent strips. Lancet. 1995;345:1290–1291. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90931-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drain P, Hyle E, Noubary F. Diagnostic point-of-care tests in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:239–249. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smalley D, Doyle V, Duckworth J. Correlation of leukocyte esterase detection and the presence of leukocytes in body fluids. Am J Med Technol. 1982;48:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckmann J, Engelhardt A, Druschky A, Mück-Weymann M, Neundörfer B. Urine test strips for cerebrospinal fluid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Med Klin (Munich) 1996;91:766–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hastka J, Hehlmann R. Meningitis–exclusion by uric test strips. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1992;117:38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oses Salvador J, Zarallo Cortés L, Cardesa García J. Useful ness of reactive strips in the diagnosis of suppurative meningitis, at the patient’s bedside. An Esp Pediatr. 1988;29:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molyneux E, Walsh A. Caution in the use of reagent strips to diagnose acute bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 1996;348:1170–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisharda A, Chowdhury R, Puliyel J. Evaluation of leukocyte esterase reagent strips for rapid diagnosis of pyogenic meningitis. Indian Pediatr. 2016;77:203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanelli R, Thome E, Duarte F, Gomes R, Camargos P, Freire H. Diagnosis of meningitis with reagent strips. J Pediatria. 2001;77:203–208. doi: 10.2223/jped.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parmar R, Warke S, Sira P, Kamat J. Rapid diagnosis of meningitis using reagent strips. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar A, Debata P, Ranjan A, Gaind R. The role and reliability of rapid bedside diagnostic test in early diagnosis and treatment of bacterial meningitis. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;82:311–314. doi: 10.1007/s12098-014-1357-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller P, Donald P. Reagent strips in the evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid glucose levels. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1987;7:287–289. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1987.11748527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall R, Hejamanowski C. Urine test strips to exclude cerebral spinal fluid blood. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:63–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maclennan C, Banda E, Molyneux E, Green D. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis using nitrite patch testing. Trop Doct. 2016;34:231–232. doi: 10.1177/004947550403400417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green D, Ansari B, Davis S, Cameron D. Reagent strip testing of cerebrospinal fluid. Trop Doct. 2003;33:31–32. doi: 10.1177/004947550303300114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Detailed approaches to assessing data from the included studies.

Appendix S2. Listed below are the studies obtained on PubMed.