Abstract

In this paper we successfully developed a procedure to generate the (+) supercoiled (sc) plasmid DNA template pZXX6 in the milligram range. With the availability of the (+) sc DNA, we are able to characterize and compare certain biochemical and biophysical properties of (+) sc, (−) sc, and relaxed (Rx) DNA molecules using different techniques, such as UV melting, circular dichroism, and fluorescence spectrometry. Our results show that (+) sc, (−) sc, and Rx DNA templates can only be partially melted due to the fact that these DNA templates are closed circular DNA molecules and the two DNA strands cannot be completely separated upon denaturation at high temperatures. We also find that the fluorescence intensity of a DNA-binding dye SYTO12 upon binding to the (−) sc DNA is significantly higher than that of its binding to the (+) sc DNA. This unique property may be used to differentiate the (−) sc DNA from the (+) sc DNA. Additionally, we demonstrate that E. coli topoisomerase I cannot relax the (+) sc DNA. In contrast, E. coli DNA gyrase can efficiently convert the (+) sc DNA to the (−) sc DNA. Furthermore, our dialysis competition assays show that DNA intercalators prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA.

Keywords: (+) sc DNA, (−) sc DNA, Rx DNA, DNA topoisomerase, intercalators

Graphical abstract

DNA supercoiling plays important roles in several essential DNA metabolic pathways, such as DNA replication, recombination, and transcription [1,2]. In almost all living organisms, DNA is typically underwound, which results in negative (−) supercoiling of the DNA template [3]. For instance, DNA (−) supercoiling status in bacteria is a result of combined activities of bacterial DNA topoisomerase I, IV, and gyrase [4,5]. For eukaryotes, DNA (−) supercoiling mainly stems from the binding of nucleosomes to DNA and topoisomerase activities [6]. One of the most important functions of (−) DNA supercoiling is to help organisms overcome energetic barriers to initiate DNA replication and transcription [1].

Positive (+) DNA supercoiling also exits in all organisms. DNA tracking motors, such as DNA replication and transcription machineries, can produce transient (+) supercoils in the front of these machineries [7,8]. These (+) DNA supercoils must be removed to prevent the arrest of the DNA replication and transcription machineries [2]. Another example of (+) DNA supercoiling comes from hyperthermophillic Archaea. Previous results showed that all hyperthermophillic Archaea have at least one reverse gyrase, a type of DNA topoisomerases that introduce (+) DNA supercoils into DNA [9,10]. Recent studies demonstrated that reverse gyrase is critical for the growth of hyperthermophillic Archaea at high temperatures [11]. Additionally, highly (+) supercoiled (sc) DNA exists in the Sulfolobus shibatae virus 1 (SSV1) [12]. These results suggest that (+) sc DNA is important for hyperthermophillic Archaea. Nevertheless, biochemical and biophysical properties of (+) sc DNA molecules have not been fully explored partially due to the fact that large amounts of (+) sc DNA templates is not easy to produce. In this paper, we generate the (+) sc plasmid DNA template pZXX6 in the milligram range using Archaeoglobus fulgidus DNA reverse gyrase followed by CsCl-EB centrifugation banding. With sufficient amount of (+) sc pZXX6, we characterize certain biochemical and biophysical properties of the (+) sc DNA using different techniques, such as UV melting, circular dichroism, fluorescence spectrometry and DNA topoisomerase assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Purification

E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS carrying the plasmid pRGYIN [13,14] was grown at 37°C in LB until OD600 reached ~0.5. The expression of the Archeoglobus fulgidous DNA reverse gyrase was then induced by adding 1 mM of IPTG to the cell culture with an additional of 3 hours of incubation at 37°C. Protein purification was then carried out using a Ni-NTA column followed by a simple precipitation step under the low salt condition in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF (the precipitation was conducted in a dialysis bag at 4°C overnight). The precipitate containing reverse gyrase was dissolved into the dialysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol) and dialyzed against the dialysis buffer overnight. The purified reverse gyrase was stored at −80°C. Bradford Assay was used to monitor the protein purification. An extinction coefficient of 3.85 mg/mL at OD280 was used to determine the concentration of the reverse gyrase.

Production of the (+) sc DNA template

The generation of the (+) sc DNA pZXX6 from the (−) sc pXXZ6 was carried out in 1×NEBuffer 4 (20 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.9, 50 mM KAc, 10 mM Mg(AC)2), 100 μg/mL BSA, and 1 mM ATP) in the presence of the purified reverse gyrase at 85°C for 30 minutes. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA; final concentration 0.5 mM) and proteinase K (final concentration 0.5 mg/mL) was added to the reaction mixtures to stop the reaction and incubated at 50°C for 30 minutes to digest the proteins in the mixtures. A phenol extraction was then carried out to remove proteins. An Ethidium Bromide-Cesium Chloride (EB-CsCl) density gradient centrifugation was used to purify the (+) sc DNA.

Circular Dichroism Spectropolarimetry

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectropolarimetry was be used to analyze the DNA topology of the (−) or (+) sc DNA pXXZ6 by using a Jasco J-815 Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectropolarimeter. Spectra was measured with a temperature range of 25 to 95° C with 10° C intervals and a wavelength of 200–350 nm.

UV Melting studies

DNA UV melting curves were determined using a Cary 100 UV-Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a thermoelectric temperature-controller. The relaxed (Rx), (−) sc, and (+)sc DNA pXXZ6 in 1×BPE buffer (6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7) was used for melting studies. Samples were heated at a rate of 1°C min−1, while continuously monitoring the absorbance at 260 nm. Primary data were transferred to the graphic program Origin (MicroCal, Inc., Northampton, MA) for plotting and analysis.

Fluorescence emission spectroscopy studies

Fluorescence emission spectroscopy studies were used to measure fluorescence intensity of a fluorophore upon binding to the (−) or (+) sc DNA pXXZ6 in 1×BPE buffer using a Fluoromax3 fluorometer.

E. coli Topoisomerase I relaxation assays

E. coli Topoisomerase I relaxation assays containing the (+) or (−) sc plasmid DNA pZXX6 were carried out in 1×NEBuffer 4 in the presence of E. coli DNA topoisomerase I. After the reaction, the DNA samples were extracted once with phenol and analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel in 1×TAE buffer containing 40 mM Tris acetate and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.2. After electrophoresis, the agarose gel was stained with Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) and photographed using a Kodak imaging system.

DNA Gyrase supercoiling activities

DNA Gyrase supercoiling activities were carried out containing the (+) sc or Rx plasmid DNA pXXZ6 in the presence of E. coli DNA gyrase in 1×DNA gyrase buffer (35 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 24 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM spermidine, 1.75 mM ATP, 5% glycerol). The DNA samples were then incubated at 37°C at different time intervals. After phenol extraction, the DNA samples were loaded to a 1% agarose gel in 1×TAE buffer in the absence or presence of 20 μg/mL chloroquine and run at a voltage gradient of 100 V for 16 h at room temperature. The gels were stained with a solution of 0.06 μL/mL Ethidium Bromide for 3 hours, destained, photographed by a Kodak imaging system.

Competition Dialysis experiments

The competition dialysis assays were carried out according to the previously published procedure [15]. Briefly, a volume of 0.3 mL of 75 μM (bp) of (+) sc, (−) sc, and Rx plasmid pXXZ6 was pipeted into a separate 0.3 mL disposable dialyzer. The dialysis units were then placed into a beaker with 250 mL of 1×BPES buffer (6 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 185 mM NaCl pH 7) containing 1 μM of one of the DNA intercalators (ethidium bromide, proflavine, and doxorubicin) or minor groove binders (netropsin and Hoechst 33258). The dialysis was allowed to equilibrate with continuous stirring for 72 hours at room temperature (24°C). After the dialysis, the free, bound, and total concentrations of DNA intercalators or groove binders were determined spectrophotometrically. These values were used to determine the DNA binding constant and free energy (ΔG) of these DNA-binding compounds to the (+) sc, (−) sc, and Rx plasmid pXXZ6. The DNA binding free energy difference of the DNA binding compounds between the (+) and (−) sc DNA (ΔΔG) was calculated:

| (1) |

Where ΔGNg and ΔGPs represent the DNA binding free energy of the compound binding to (−) and (+) sc DNA templates, respectively.

Results and discussion

Optical properties of (+) sc DNA molecules

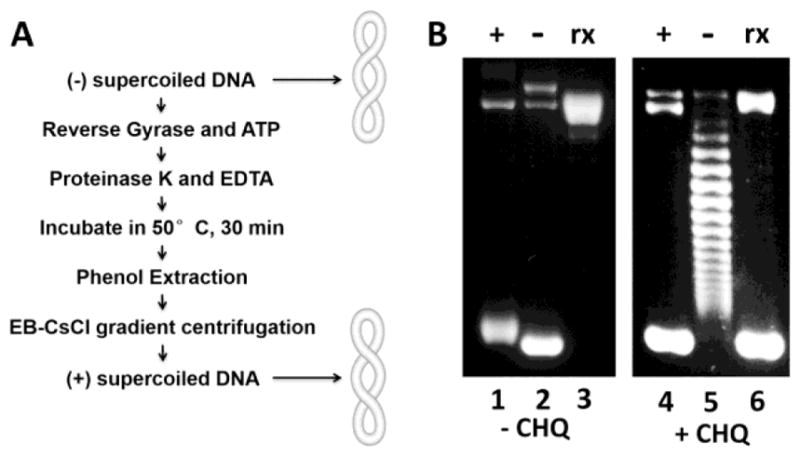

Here we successfully developed a procedure to generate the (+) sc plasmid DNA pZXX6 in the milligram range in order to study its biochemical and biophysical properties. Fig. 1A shows the procedure. Intriguingly, ethidium bromide was able to separate the (+) sc DNA from nicked (Nk) DNA templates in the EB-CsCl gradient centrifugation. Our agarose gel analysis demonstrated that more than 95% of DNA templates are (+) sc (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 5).

Fig. 1. Preparation of the (+) sc plasmid DNA template pZXX6 in the milligram range.

(A) An experimental scheme of generating the (+) sc plasmid DNA template pZXX6 in the milligram range. (B) 1% agarose gels for the (+) sc (lane 1 and 4), (−) sc (lane 2 and 5) and Rx (lane 3 and 6) plasmid pXXZ6 in the absence (left) or presence (right) of chloroquine (20 μg/ml).

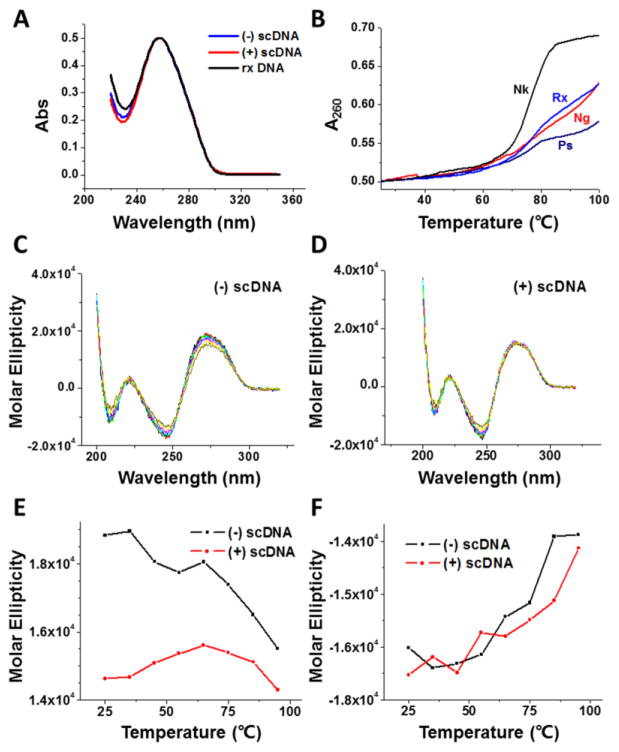

After obtaining sufficient amounts of the (+) sc DNA template, we measured the UV absorbance spectra of the (+), (−), and Rx DNA samples (Fig. 2A). As expected, the UV absorbance spectra of these three DNA templates are almost identical. We also carried out UV melting studies for the (+), (−), Rx, and Nk DNA samples. As anticipated, the Nk DNA plasmid shows a normal DNA melting curve with an estimated melting temperature of 76 °C (Fig. 2B). Intriguingly, Rx, (−) sc, and (+) sc DNA templates can only be partially melted. The increases of absorbance at 260 nm (hyperchromicity) between 25 and 100 °C are 38%, 26%, 26%, and 16% for Nk, Rx, (−) sc, and (+) sc plasmid DNA templates, respectively (Fig. 2B). These reduced hyperchromicity of Rx, (−) sc, and (+) sc plasmid DNA templates is due to the fact that these DNA templates are closed circular DNA molecules and the two DNA strands cannot be completely separated upon denaturation at high temperatures. Nevertheless, the (+) sc plasmid DNA template has the least increase in absorbance at 100 °C and suggests that its two strands are the most resistant to thermal denaturation.

Fig. 2. Optical properties of (+) sc, (−) sc, Rx, and Nk DNA templates.

(A) UV absorption spectra of the (+) sc, (−) sc, and Rx plasmid pXXZ6 in 1×BPE buffer. (B) DNA UV melting curves of the (+) sc, (−) sc, Rx, and Nk plasmid DNA template pXXZ6 in 1×BPE buffer. (C–F) CD spectra of (+) and (−) supercoiled plasmid pXXZ6 at different temperatures in 1×BPE buffer.

Next, we carried out circular dichroism (CD) studies for (+) and (−) sc DNA templates. Fig. 2C–F show the CD spectra of both DNA samples. Fig. 2C and D display the molar ellipticity of (+) and (−) sc DNA from 180 to 320 nm, respectively. Each line displayed on the graph represents a CD spectrum at a different temperature. Some difference between both DNA samples was observed at 272 nm (Fig. 2E). For instance, the molar ellipticity of the (−) sc DNA sample is significantly greater than that of the (+) sc DNA sample at 25°C. For the (−) sc DNA template, the molar ellipticity continuously decreased upon increasing temperature. In contrast, the molar ellipticity of the (+) sc DNA template was first increased and then decreased when temperature was increased. Nevertheless, the fluctuation of the molar ellipticity for the (+) sc DNA template is much smaller comparing with that of the (−) sc DNA template. Additionally, we also observed the increase of molar ellipticity at 245 nm for both (+) and (−) sc DNA templates upon the increase of temperature (Fig. 2F).

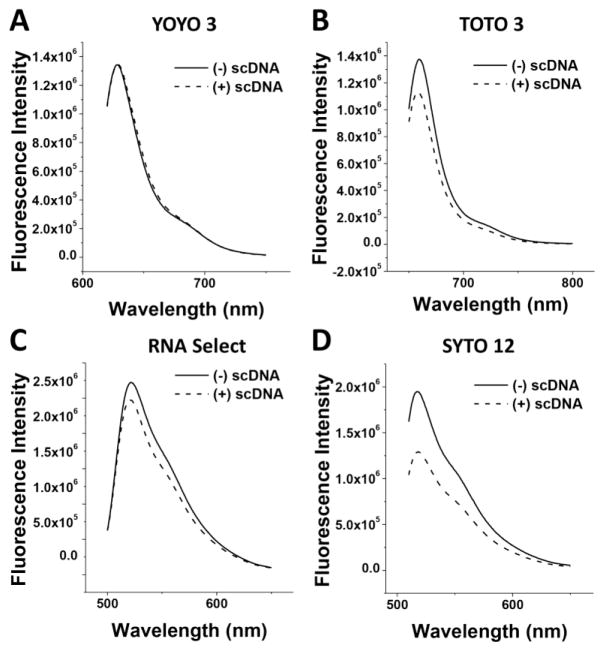

In this study, we also determined the fluorescence emission spectra of certain DNA-binding compounds upon binding to (+) and (−) sc DNA templates. Fig. 3 shows results of the four DNA-binding compounds with different fluorescence characteristics. No difference was observed for the DNA-binding dye YOYO3 (Fig. 3A). The fluorescence intensity is higher for TOTO3, RNA Select, and SYTO12 upon binding to the (−) sc DNA template than that of these DNA binding dyes binding to the (+) sc DNA template (Fig. 3B–D). Interestingly, the fluorescence intensity is significant higher for SYTO12 when it binds to the (−) sc DNA samples (Fig. 3D). This unique property of SYTO12 may be used to study DNA topology and screen inhibitors targeting various DNA topoisomerases.

Fig. 3. Fluorescence emission spectra of four different DNA-binding dyes upon binding to the (+) and (−) supercoiled plasmid pXXZ6 in 1×BPE buffer.

(A) YOYO 3 with λex = 640 nm. (B) TOTO 3 with λex = 610 nm. (C) RNA Select with λex = 499 nm. (D) SYTO 12 with λex = 490 nm.

DNA Gyrase is able to efficiently convert (+) sc DNA to (−) sc DNA

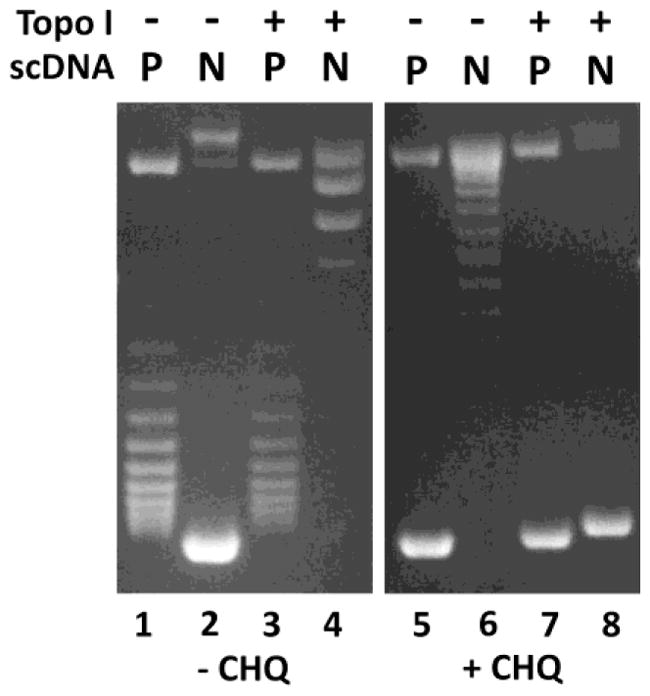

Although E. coli has four different DNA topoisomerases, i.e., topoisomerase I, gyrase, topoisomerase III, and topoisomerase IV, the DNA topology inside of the cells is set primarily by the counter actions of DNA topoisomerase I and gyrase [4,5]. The primary function of E. coli DNA topoisomerase I is to remove the excess (−) supercoils of the DNA templates generated during DNA replication, recombination, and transcription [16]. It cannot remove (+) supercoils from the DNA templates since it requires the single stranded DNA for its action [17,18]. Indeed, our results in Fig. 4 show that E. coli DNA topoisomerase I cannot remove (+) supercoils from the (+) sc DNA template (compare lanes 1 and 3, and lanes 5 and 7) although it efficiently convert the (−) sc DNA template to the Rx DNA (compare lanes 2 and 4). This result is consistent with the previously published result [18].

Fig. 4. E. coli DNA topoisomerase I is able to relax the (−) sc DNA but cannot relax the (+) sc DNA.

1% agarose gels in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 5 μg/mL of chloroquine (CHQ). P and N represent positively or negatively sc DNA, respectively.

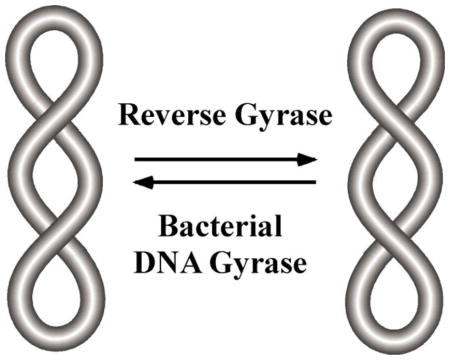

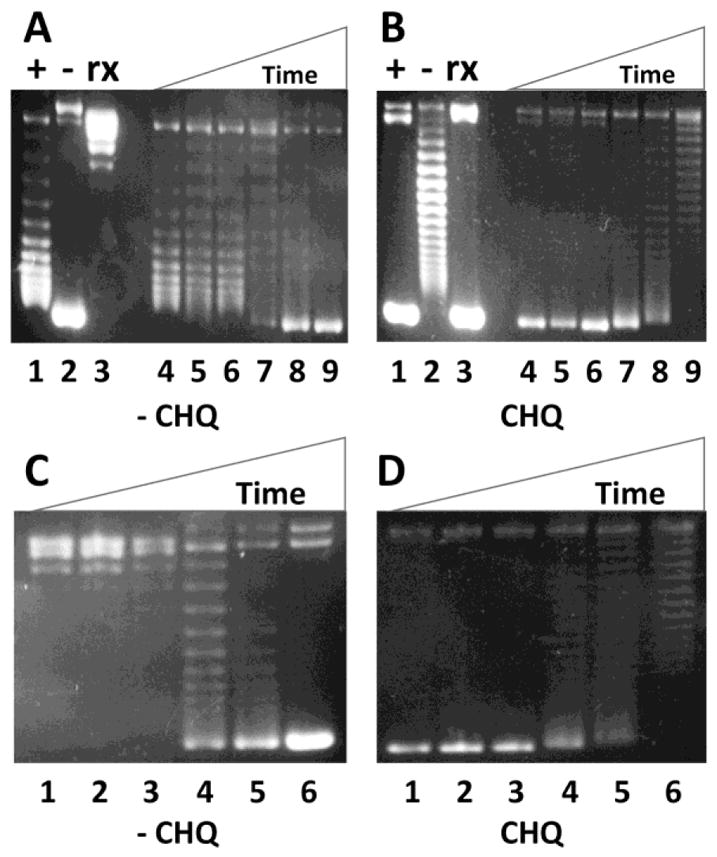

We also tested whether E. coli DNA gyrase is able to convert the (+) sc DNA to the (−) sc DNA. Fig. 5 shows our results. From these time course studies, we conclude that E. coli DNA gyrase is able to efficiently convert the (+) sc DNA templates to the (−) sc DNA. The conversion efficiency is comparable to that of converting the Rx DNA to the (−) sc DNA (Fig. 5). This result suggests that bacterial DNA gyrase can efficiently remove (+) supercoils ahead of the DNA replication fork during DNA replication elongation. Likewise, bacterial DNA gyrase may also remove (+) supercoils in the front of RNA polymerase to facilitate transcription elongation [7].

Fig. 5. E. coli DNA gyrase is able to efficiently convert the (+) sc DNA to the (−) sc DNA.

DNA gyrase supercoiling assays were performed as described under Materials and Methods. (A) & (B) 1% agarose gels in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 20 μg/mL of chloroquine to show the efficient conversion of the (+) sc pXXZ6 to the (−) sc DNA by E. coli DNA gyrase. Lanes 1 to 3 represent the (+) sc, (−) sc, and Rx plasmid pZXX6, respectively. Lanes 4 to 9 represent the DNA products after 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 30 min DNA supercoiling reactions by E. coli DNA gyrase, respectively. (C) & (D) 1% agarose gels in the absence (C) and presence (D) of 20 μg/mL of chloroquine to show the efficient conversion of the Rx pXXZ6 to the (−) sc DNA by E. coli DNA gyrase. Lanes 1 to 6 represent the DNA products after 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 30 min DNA supercoiling reactions by E. coli DNA gyrase, respectively.

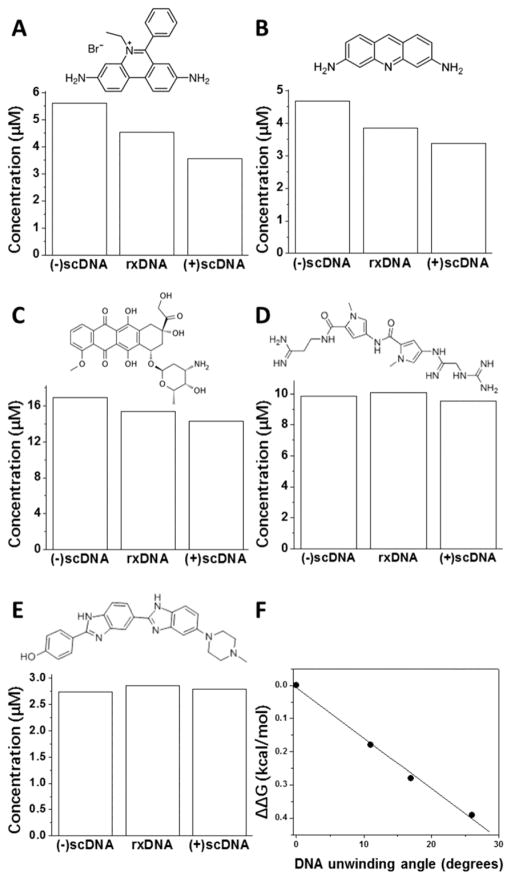

DNA intercalators prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA template

Many natural compounds strongly bind to DNA. These DNA-binding compounds include DNA intercalators and minor groove binders [15,19]. Previous studies showed that DNA intercalators, such as ethidium bromide, can unwind DNA and, as a result, cause relaxation of closed circular plasmid DNA templates [19,20]. Because of this unique property of DNA intercalators, they should prefer binding to (−) sc DNA templates over Rx and (+) sc DNA molecules. DNA competition dialysis assays were employed to examine whether DNA intercalators ethidium bromide, proflavine, and doxorubicin bind more tightly to the (−) sc DNA molecules than the Rx and (+) sc DNA (Fig. 6). Indeed, all three DNA intercalators, ethidium bromide, proflavine, and doxorubicin prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA over the Rx and (+) sc DNA. The DNA binding affinity is the strongest to the (−) DNA and the weakest to the (+) DNA. For example, in the DNA competition dialysis assay for ethidium bromide, the DNA bound ethidium for (−), rx, and (+) DNA were determined to be 4.02, 3.52, and 2.18 μM after dialysis. These values were used to calculate ΔΔG to be −0.39 kcal/mol according to equation 1. In contrast, two minor groove binders netropsin and hoechst33258 bind to all three forms of DNA templates with the same DNA binding affinity. Interestingly, the DNA binding free energy difference of the DNA intercalators between the (−) and (+) sc DNA (ΔΔG) is proportional to their DNA unwinding angles (Fig. 6F) [19]. These results suggest that ΔΔG stems from the unwinding capacity of these DNA intercalators.

Fig. 6. DNA intercalators prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA template.

The competition dialysis assays for the (−) sc, (+) sc, and Rx plasmid DNA pXXZ6 against three DNA intercalators (ethidium bromide (A), proflavine (B), and doxorubicin (C)) and two minor groove binders (netropsin (D) and hoechst33258 (E)) in 1×BPES buffer were performed as described under Materials and Methods. (F) The DNA binding free energy difference of the DNA intercalators between the (−) and (+) sc DNA (ΔΔG) is linearly proportional to their DNA unwinding angles.

Summary

We developed a simple procedure to produce (+) sc plasmid DNA templates in the milligram range and showed that Rx, (−), and (+) DNA templates could only be partially melted. We also find that the fluorescence intensity of a DNA-binding dye SYTO12 upon binding to the (−) sc DNA is significantly higher than that of its binding to the (+) sc DNA. Additionally, we demonstrate that E. coli topoisomerase I cannot relax the (+) sc DNA. In contrast, E. coli DNA gyrase is able to efficiently convert the (+) sc DNA to the (−) sc DNA. Finally, we carried out dialysis competition assays and show that DNA intercalators prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA. The (+) sc plasmid DNA templates are good substrates for bacterial DNA gyrase and may help develop assays to identify potential antibiotics targeting bacterial DNA gyrase. Because (+) sc DNA is more stable, another potential application of the (+) sc DNA is to produce DNA vaccine.

Highlights.

A simple procedure to generate (+) sc plasmid DNA templates in the milligram range.

Rx, (−), and (+) DNA templates can only be partially melted.

Fluorescence dye SYTO12 can differentiate the (+) and (−) sc DNA.

Bacterial DNA gyrase efficiently converts the (+) sc DNA to the (−) sc DNA.

DNA intercalators prefer binding to the (−) sc DNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 1R15GM109254-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health (to F.L.).

Abbreviations symbols and terms

- sc

supercoiled

- Rx

relaxed

- Nk

nicked

- (+)

positive or positively

- (−)

negative or negatively

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bates AD, Maxwell A. DNA Topology. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang James C. Untangling the Double Helix: DNA Entanglement and the Action of the DNA Topoisomerases. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cozzarelli NR, Wang JC. DNA Topology and Its Biological Effects. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snoep JL, van der Weijden CC, Andersen HW, Westerhoff HV, Jensen PR. DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli is under tight and subtle homeostatic control, involving gene-expression and metabolic regulation of both topoisomerase I and DNA gyrase. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1662–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2002.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zechiedrich EL, Khodursky AB, Bachellier S, Schneider R, Chen D, Lilley DM, Cozzarelli NR. Roles of topoisomerases in maintaining steady-state DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8103–8113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu LF, Wang JC. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postow L, Crisona NJ, Peter BJ, Hardy CD, Cozzarelli NR. Topological challenges to DNA replication: conformations at the fork. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8219–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111006998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi A, Asai K. Reverse gyrase--a topoisomerase which introduces positive superhelical turns into DNA. Nature. 1984;309:677–681. doi: 10.1038/309677a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lulchev P, Klostermeier D. Reverse gyrase--recent advances and current mechanistic understanding of positive DNA supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8200–8213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipscomb GL, Hahn EM, Crowley AT, Adams MWW. Reverse gyrase is essential for microbial growth at 95 degrees C. Extremophiles. 2017;21:603–608. doi: 10.1007/s00792-017-0929-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadal M, Mirambeau G, Forterre P, Reiter WD, Duguet M. Positively supercoiled DNA in a virus-like particle of an archaebacterium. Nature. 1986;321:256–258. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh TS, Plank JL. Reverse gyrase functions as a DNA renaturase: annealing of complementary single-stranded circles and positive supercoiling of a bubble substrate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5640–5647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez AC, Stock D. Crystal structure of reverse gyrase: insights into the positive supercoiling of DNA. EMBO J. 2002;21:418–426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren J, Chaires JB. Sequence and structural selectivity of nucleic acid binding ligands. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16067–16075. doi: 10.1021/bi992070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JC. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JC. Interaction between DNA and an Escherichia coli protein omega. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:523–533. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkegaard K, Wang JC. Bacterial DNA topoisomerase I can relax positively supercoiled DNA containing a single-stranded loop. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:625–637. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloomfield VA, Crothers DM, Tinoco I., Jr . Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties, and Functions. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neidle S, Abraham Z. Structural and sequence-dependent aspects of drug intercalation into nucleic acids. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1984;17:73–121. doi: 10.3109/10409238409110270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]