Abstract

Most forms of arthritis are incurable, difficult to treat, and a major cause of disability in Western countries. Better local treatment of arthritis is impaired by the pharmacokinetics of the joint that make it very difficult to deliver drugs to joints at sustained, therapeutic concentrations. This is especially true of biologic drugs, such as proteins and RNA, many of which show great promise in preclinical studies. Gene transfer provides a strategy for overcoming this limitation. The basic concept is to deliver cDNAs encoding therapeutic products by direct intra-articular injection, leading to sustained, endogenous synthesis of the gene products within the joint. Proof of concept has been achieved for both in vivo and ex vivo gene delivery using a variety of vectors, genes, and cells in several different animal models. There have been a small number of clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) using retrovirus vectors for ex vivo gene delivery and adeno-associated virus (AAV) for in vivo delivery. AAV is of particular interest because, unlike other viral vectors, it is able to penetrate deep within articular cartilage and transduce chondrocytes in situ. This property is of particular importance in OA, where changes in chondrocyte metabolism are thought to be fundamental to the pathophysiology of the disease. Authorities in Korea have recently approved the world's first arthritis gene therapy. This targets OA by the injection of allogeneic chondrocytes that have been transduced with a retrovirus carrying transforming growth factor-β1 cDNA. Phase III studies are scheduled to start in the United States soon. Meanwhile, two additional Phase I trials are listed on Clinicaltrials.gov, both using AAV. One targets RA by transferring interferon-β, and the other targets OA by transferring interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. The field is thus gaining momentum and promises to improve the treatment of these common and debilitating diseases.

Keywords: : arthritis, cartilage, synovium, joint disease, intra-articular therapy

Introduction

Joints are organs of locomotion, subject to >100 different forms of arthritis. Although disorders of joints are rarely lethal, they are very common, often chronic, and frequently a source of considerable misery, disability, and economic loss. Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, affected nearly 27 million Americans in 2005 (1), with an economic burden exceeding $186 billion per annum (2). Moreover, the prevalence of OA is rising, as two of its major risk factors—age and body mass index—increase in society. According to the Center for Disease Control, arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States, followed by back problems and cardiac issues (3). Other common forms of arthritis include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis, and gout. The various arthritides are projected to affect 63 million Americans by 2020 (https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/national-statistics.html). Nearly all forms of arthritis are incurable, and most are difficult to treat.

As described in this review, local gene delivery to diseased joints by intra-articular injection holds promise as a means of improving the treatment of the arthritides. Because the early research into these topics has been thoroughly covered in previous reviews (4–6), the present one focuses on recent trends and, in particular, translation, clinical trials, and the development of clinical products, the first of which has just been approved in Korea.

The Structure of Diarthrodial Joints

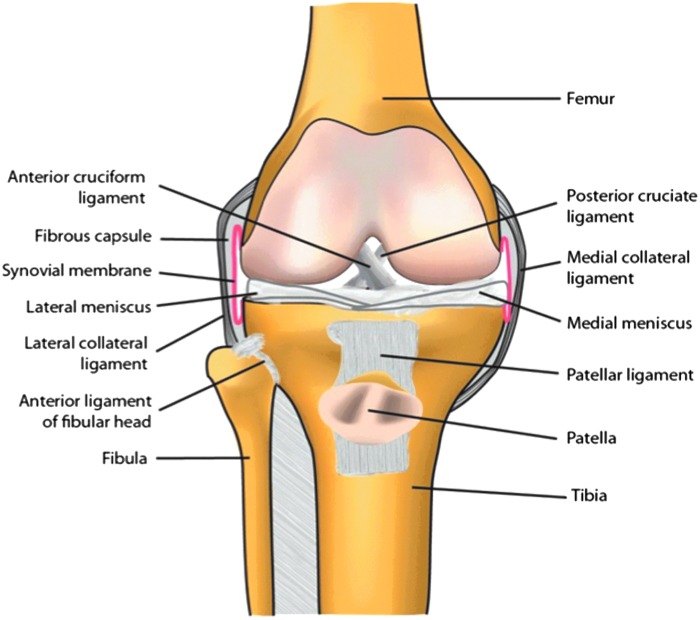

Diarthrodial (synovial) joints are organs within which the ends of bones articulate (Fig. 1). The load-bearing surfaces of the bones are covered with articular cartilage, which provides a resilient, almost frictionless, coating with the ability to rebound after deformation. Articular cartilage is avascular, aneural, and alymphatic—circumstances that contribute to its inability to repair spontaneously. This deficiency may be exacerbated by the possible absence of stem/progenitor cells, although Archer's group has described a population of progenitor cells at the surface of cartilage (7), while others have suggested the existence of rare progenitor cells deeper within the tissue (8). Nevertheless, the bulk of the cartilage contains a sparse population of non-mitotic chondrocytes within an abundant, dense extracellular matrix (ECM) largely comprising collagens and proteoglycans (9,10).

Figure 1.

Basic anatomy of the human knee joint.

Knees and certain other joints contain additional cartilagenous structures called menisci that serve as shock absorbers and help to distribute load throughout the joint. They are frequently damaged through injury, but only the outer third of the meniscus in the knee is vascularized and thus able to heal. Until relatively recently, damaged menisci were surgically removed. This relieved pain, swelling, and locking in the short term, but predisposed the joint to post-traumatic OA. Current practice aims for repair with preservation of as much of the original meniscal tissue as possible (10).

Certain joints have intra-articular ligaments, such as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and tendons, such as the patellar tendon, of the knee. The ACL, in particular, is frequently torn as a result of injury and does not repair spontaneously (11). Rupture of the ACL frequently leads to post-traumatic OA. The knee also has a large infra-patellar fat pad that is receiving increased attention in the context of OA and its association with obesity (12).

Unlike most body cavities, the joint space is not lined by basement membrane. Instead, the surrounding connective tissue capsule merges with a structure identified anatomically as the synovial membrane or synovium. This collagenous structure contains both macrophages, historically known as type A synoviocytes, and fibroblasts (type B synoviocytes) (13). Recent reports suggest the presence of mesenchymal progenitor cells within synovium (14). Abundant sub-synovial capillaries and lymphatics supply the area (15). Normal joints contain a small volume of synovial fluid, which is a dialysate of blood entering the joint via the fenestrated synovial capillaries and synovial interstitium, into which synovial fibroblasts secrete hyaluronic acid and lubricin as lubricants.

The main pathologies common to the various forms of arthritis include synovial inflammation (synovitis), increased volume and cellularity of synovial fluid (effusion), breakdown of cartilage (degeneration), and alterations to the subchondral bone. These produce the dominant clinical symptom of arthritis—pain (16). Much of the therapeutic effort in gene therapy has been devoted to delivering to joints products that are anti-inflammatory, that inhibit the breakdown of cartilage, or that promote the synthesis of repair cartilage.

Why Gene Therapy

With the exception of RA and related autoimmune conditions, disorders of joints tend to be local and usually affect a small number of joints—often only one. Such circumstances favor intra-articular therapies, where the therapeutic agent is delivered directly to the affected joint. Compared to systemic delivery, this reduces the likelihood of adverse events in non-target organs, maximizes the concentration of the therapeutic at the site of disease, and, by treating a joint instead of the whole body, lowers cost. Joints are discrete, enclosed cavities (Fig. 1), and most are readily accessible to intra-articular injection, which is the delivery method of choice.

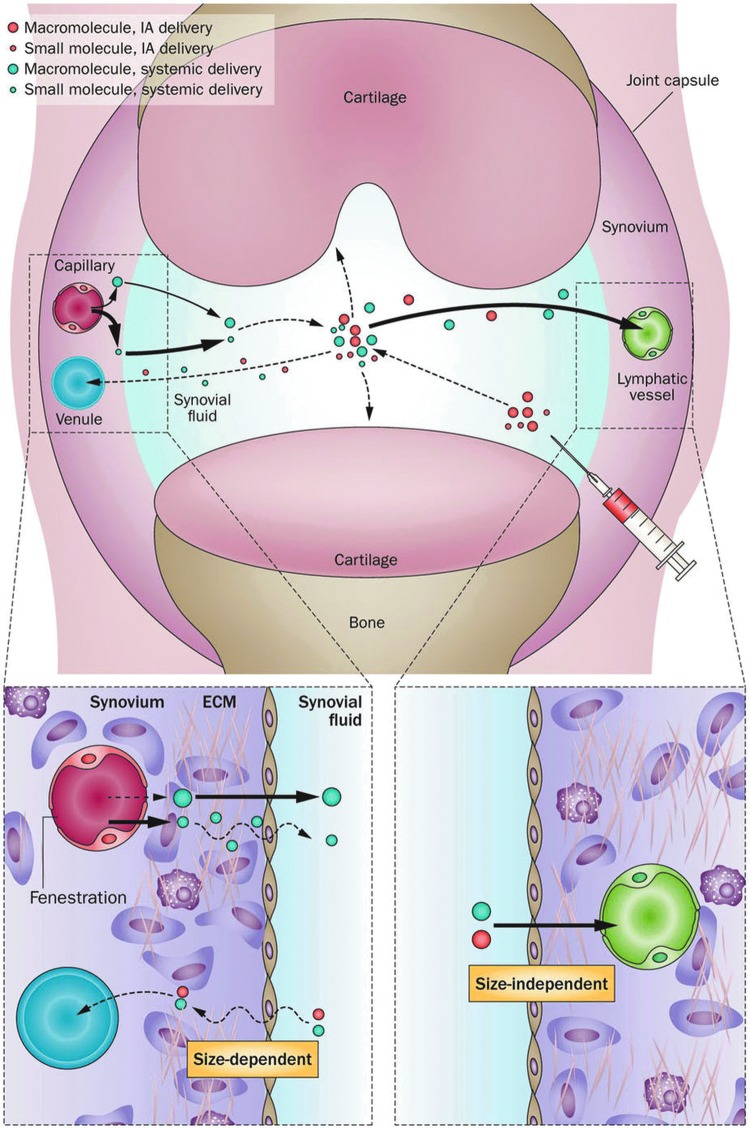

Although it is a straightforward matter to inject therapeutics into joints, the effectiveness of intra-articular therapy is greatly compromised by the rapidity and efficiency with which material leaves the synovial space (17). Small molecules diffuse out through the sub-synovial capillaries, while macromolecules and particles leave through the lymphatics (Fig. 2). It is thus very difficult to achieve sustained, therapeutic concentrations of drugs in joints. The idea to use gene therapy for joint disorders arose in response to this problem.

Figure 2.

How molecules get into and out of joints. Macromolecules in the circulation enter the joint via the synovial capillaries and are sieved by the fenestrated endothelium of the capillaries. Small molecules also enter via the capillaries, but the major resistance to their entry is provided by the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the synovial interstitium. Intra-articular (IA) injection bypasses both of the constraints to entry. However, both large and small molecules rapidly exit the joint via the lymphatic system and small blood vessels, respectively. From Evans et al.17

The original concept was to target gene delivery to the synovium for treating arthritis (18). This would lead to the sustained synovial synthesis of therapeutic gene products locally within joints. Such a strategy also obviates another problem for treating joints with biologics, namely the restricted access of proteins and other large molecules to the interior of the joint from the circulation. This restriction reflects the sieving effect of the fenestrated endothelium of the sub-synovial capillaries and the synovial interstitium through which such molecules must diffuse (17).

Inefficiencies of protein delivery to joints from the circulation are reflected in the intra-articular pathologies that affect patients with two genetic diseases: mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (MPS VI) and hemophilia. MPS VI results from a deficiency in the lysosomal enzyme N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase. Intravenous delivery of the recombinant protein successfully treats extra-articular manifestations of disease, but it fails to prevent joint degeneration. However, periodic intra-articular injection of the protein in the feline version of MPS VI maintains joint integrity (19). A lentivirus carrying N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase corrects the phenotype of MPS VI cells and is being tested as a vector for intra-articular delivery in animal models (20). An analogous circumstance exists for hemophilia where, despite the systemic administration of clotting factors, hemophiliacs suffer from repeated bleeding into the joint that leads to a characteristic, severe hemarthropathy. Data from a murine model suggest that intra-articular delivery of clotting factor genes protects the joint far more efficiently than systemic delivery of the recombinant clotting factor proteins (21).

Local, Intra-Articular Gene Therapy for Arthritis

Gene delivery strategies

Although vectors or genetically modified cells can be surgically implanted into joints, a procedure commonly investigated for the tissue engineering of intra-articular structures such as cartilage (22), this review focuses on delivery by intra-articular injection feasible through a small-gauge needle in an outpatient setting.

A considerable literature confirms the feasibility of introducing cDNAs into joints by simple injection and expressing them intra-articularly (4–6). Ex vivo delivery has been achieved with vectors derived from oncoretrovirus (23–27), foamy virus (28), and adenovirus (29,30) used in conjunction with different mesenchymal cell types in the joints of various laboratory animals. Ex vivo delivery to joints of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) using autologous synovial fibroblasts (31,32) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) using allogeneic chondrocytes (33–35) has been the subject of human clinical trials (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Clinical trials in the gene therapy of rheumatoid arthritis

| Transgene product | Method of delivery | Phase | PI, institution, or sponsor | ClinicalTrials.govidentifier | Status | Number of subjects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1Ra | Retrovirus, ex vivo | I | Evans and Robbins, University of Pittsburgh | Predates | Completed | 9 | 31 |

| IL-1Ra | Retrovirus ex vivo | I | Wehling, University of Düsseldorf, Germany | Predates | Completed | 2 | 32 |

| Etanercepta | AAV, in vivo | I | Mease, Targeted Genetics | NCT00617032 | Completed | 15 | 57 |

| Etanerceptb | AAV, in vivo | I/II | Mease, Targeted Genetics | NCT00126724 | Completed | 127 | 56 |

| IFN-β | AAV, in vivo | Preclinical | Tak, Arthrogen | NCT02727764 | Recruiting | 12 |

Included one subject with ankylosing spondylitis.

Included subjects with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis.

PI, principal investigator; IL-1Ra, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; IFN, interferon.

Table 2.

Clinical trials in the gene therapy of osteoarthritis

| Transgene | Method of delivery | Phase | PI, institution, or Sponsor | Clinical Trials.govidentifier | Status | Number of subjects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | I | Ha, Kolon Life Sciences, Korea | NCT02341391 | Completed | 12 | 34 |

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | I | Mont, TissueGene, Inc. | NCT00599248 | Completed | 9 | |

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | II | Ha, Kolon Life Sciences, Korea | NCT01671072 | Completed | 54 | |

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | IIa | Ha, Kolon Life Sciences, Korea | NCT02341378 | Completed | 28 | 33 |

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | II | Mont, TissueGene, Inc. | NCT 01221441 | Completed | 100 | 35 |

| TGF-β1 | Retrovirus, ex vivo | III | Lee, Kolon Life Sciences, Korea | NCT02072070 | Completed | 163 | |

| IL-1Ra | AAV, in vivo | I | Evans, Mayo Clinic | NCT02790723 | Pending | 9 |

TGF, transforming growth factor.

Successful in vivo transduction follows the intra-articular injection of various vectors, including those derived from adenovirus (36–39), oncoretrovirus (40), herpes simplex virus (41,42), lentivirus (43–46), adeno-associated virus (AAV) (38,47–54), and a variety of different non-viral formulations (55). AAV has been used for in vivo intra-articular gene delivery in two human trials (56,57), with two more pending trials listed on Clinicaltrials.gov (Tables 1 and 2).

Because arthritis is not lethal, safety issues predominate when contemplating human application, and this places constraints on the types of vectors than can be reasonably used. As described below, the first clinical trial used oncoretroviruses to transduce autologous synovial cells that were injected into patients' joints. This approach was abandoned when the oncogenic potential of such vectors was realized in a clinical trial for severe combined immunodeficiency (58). Moreover, ex vivo therapy using expanded, autologous cells was found to be cumbersome, tedious, and expensive. A modified ex vivo approach, described in the next section, avoids this problem by using an allogeneic cell line.

One issue common to all ex vivo protocols targeted to joints is the short intra-articular dwell time of the injected cells. This matter has received considerable attention as a result of the popularity of injecting so-called mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into joints as a therapy for OA. Most investigators have found that the injected cells are cleared very rapidly from the joints of experimental animals, with few cells remaining beyond 1–2 weeks (59–61). Tracking studies confirm that before elimination, the injected cells attach to the synovial lining soon after injection with no attachment to cartilage. Some investigators suggest that MSCs home to sites of cartilage damage where they adhere and contribute to the formation of new tissue, but this is controversial.

In view of the above considerations, in vivo delivery holds many obvious advantages as a gene transfer strategy. AAV has emerged as the vector of choice for human and veterinary drug development because of its safety profile and improvements in vector design and manufacture. Of the other potential vectors for in vivo delivery, non-viral vectors give insufficient levels and duration of gene expression, herpes simplex virus is cytotoxic in joints, integrating lentiviruses raise concerns about insertional mutagenesis, and first-generation adenoviruses are immunostimulatory (55). However, it has been reported that high-capacity (“gutted”) adenovirus vectors lack these immunostimulatory properties and provide extended intra-articular transgene expression after injection into the knee joints of mice (39).

The selection of AAV serotype for gene delivery to joints has been a matter of some discussion. In vitro studies using synovial fibroblasts recovered from humans, horses, rabbits, and mice suggest that AAV serotypes 1, 2, 2.5, 3, and 5 have the highest transduction efficiencies, while AAV serotypes 8 and 9 have much weaker activity (21,51,62–65). AAV serotypes 2, 2.5, 5, 6, and 8 are effective in transducing chondrocytes in culture (21,62,63). However, the degree to which in vitro data of this kind reflect transduction efficiency in vivo is unclear, especially as cells can rapidly modulate their surface glycan populations in response to culture conditions. Watson et al., for example, noted that AAV8 gave transgene expression comparable to that of AAV2 after injection into equine joints, despite poor transduction of equine synovial fibroblasts in vitro (50). Efficient in vivo transgene expression after intra-articular injection has been noted with AAV serotypes 2, 2.5, 5, and 8 in various mammalian species (21,40,49–51,64).

Pre-existing and acquired immunity to different AAV serotypes is also an issue. More than 50% of the population has neutralizing antibodies to AAV2, which could interfere with primary and repeat dosing, especially as such antibodies are present in synovial fluid as well as serum (65,66). For this reason, there is enthusiasm for alternative serotypes, especially AAV5, for which there is less pre-existing immunity in human populations (65). Nevertheless, intra-articular injection of AAV in naïve animals generates serotype-specific neutralizing antibodies (49,67). Because the joint is a defined cavity, pre-injection lavage is a possible route to allowing intra-articular transduction in immune individuals. In addition, Mingozzi et al. (68) have noted that the immunosuppressive drugs taken by patients with RA may facilitate dosing with AAV. Whether the expression of anti-inflammatory transgenes, such as IL1RN, which encodes IL-1Ra, will influence the generation of neutralizing antibodies is an interesting question. Although cell-mediated immune responses after intra-articular injection of AAV have not been detected in laboratory animals, it remains to be seen whether intra-articular injection of AAV will trigger the production of CD8+ T-cell responses in humans (69).

There was some initial confusion concerning which tissues are transduced following the intra-articular injection of AAV. Hirsch's group, who were among the first to report in vivo transduction of synovial cells with AAV (38), subsequently suggested that the virus actually passed through the synovium and transduced underlying muscle cells (70). A subsequent study by Kyostio-Moore et al. (71) confirmed robust transduction of skeletal muscle by AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, and 8 after intra-articular injection into mouse joints, but also noted transduction of adipocytes, synovium, and chondrocytes, although the tropism varied by serotype and mouse strain.

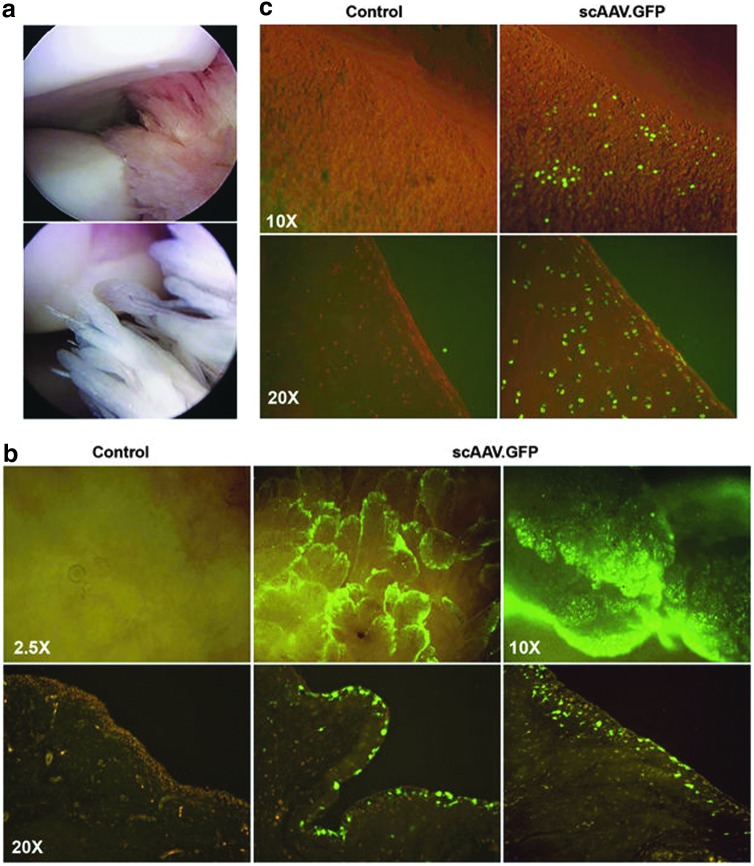

When injected into equine joints, AAV unequivocally transduces cells within synovium and cartilage (50) (Fig. 3). Although fewer chondrocytes than synovial cells are modified, the ability to transduce chondrocytes in situ is an enormous advantage when treating a disease such as OA where chondrocyte dysfunction is a key pathophysiological process. Moreover, because chondrocytes do not normally turn over, their in situ transduction by AAV provides the basis for extended periods of transgene persistence. Higher levels of transgene expression by synovium and cartilage were found in horses with OA (Ghivizzani et al., unpublished). These findings are consistent with prior data using rabbits (72) and rats (73) showing enhanced transduction of chondrocytes in areas of cartilage damage following intra-articular injection of AAV.

Figure 3.

Gene transfer to the synovium and articular cartilage of the equine joint after IA injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) green fluorescent protein (GFP). Approximately 1 × 1012 vg of scAAV.GFP packaged in serotype 2 was injected into the mid-carpal or metacarpophalangeal joints of one horse. Following sacrifice at day 10, joint tissues were harvested and analyzed for GFP expression, either directly using inverted fluorescence microscopy or following paraffin section and immunohistochemical staining. (a) Arthroscopic images of the interior of a healthy equine mid-carpal joint are shown to illustrate the anatomy and morphology of the articular tissues. The top image shows the smooth, rounded surfaces of articular cartilage with adjacent tissues of the synovial lining. The lower image illustrates the highly villous nature of the synovium. (b) scAAV.GFP expression in the synovium. (c) scAAV.GFP expression in articular cartilage. For both panels (b) and (c), the images in the top row show the distribution of GFP expression across the surfaces of the freshly harvested tissues using direct inverted fluorescence microscopy. The lower panels show GFP expression in each tissue in cross-section following paraffin section and immunohistochemical staining. From reference Watson et al.50

In vitro studies using explants of human cartilage suggest that AAV can also transduce human chondrocytes in situ (74,75). In vitro experiments by Grodzinsky's group suggest that substances with a hydrodynamic size >10 nm cannot penetrate the dense ECM of normal articular cartilage (76). The observation that particles of AAV, approximately 20 nm in diameter, can transduce chondrocytes throughout the full thickness of normal cartilage may reflect the pumping action occurring as joints are loaded and unloaded during motion. This gives AAV an unexpected advantage over larger viruses such as adenovirus and lentivirus, both of which are approximately 100 nm in diameter and which have not been reliably reported to transduce chondrocytes within the deeper zones of normal cartilage. Because arthritis is associated with the loss of the cartilagenous matrix, opportunities for transduction of chondrocytes by larger viruses may increase as the disease progresses.

The single-stranded DNA genome of AAV formerly served as an impediment to its wider use as a vector in joints. Depending on the species, inefficient second-strand synthesis by synoviocytes was seen to be limiting. One strategy for overcoming this involves ultraviolet irradiation of cells after transduction, which in the orthopedic context can be accomplished arthroscopically (54). By directing the light source to specific areas in the joint, it is possible to stimulate transduction with anatomical selectivity. The development of self-complementing AAV genomes provides a more comprehensive technology for obviating problems with the single-stranded genome.

It has recently been reported that the transduction of joint tissues following intra-articular injection of AAV can be augmented by preventing synovial macrophage function. This can be accomplished with empty AAV capsids that act as decoys, triamcinolone to suppress macrophage function, or clodronate liposomes that are toxic to macrophages (77).

Long-term and regulated transgene expression within joints

As noted, intra-articular injection of suspensions of genetically modified cells is unlikely to achieve long-term transgene expression because injected cells are cleared from joints within days to weeks.

Persistent intra-articular expression following in vivo gene delivery was only achieved when the importance of the immune system in curtailing transgene expression was fully appreciated. This followed experiments in which vectors were injected into the knee joints of athymic rats (78). Under these conditions, transduction of the synovium was initially high, but transgene expression then fell as a result of synovial cell turnover, persisting at about 25% of the early level for the rest of the animals' life-span. Similarly extended periods of transgene expression are achieved when immunologically silent vectors are used to deliver autologous gene products in wild-type animals. In the horse, for example, transgenic equine IL-1Ra has been expressed for more than a year following delivery with recombinant AAV (Ghivizzani, unpublished). Unlike the data from the athymic rat experiments, expression in equine joints did not experience such a rapid or extensive decline. This could reflect species differences or the use of adult horses versus young rats. The extensive transduction of equine chondrocytes as a long-term reservoir could also contribute to long-term transgene expression (50).

Because arthritis is associated with flares and remissions, there is interest in regulating transgene expression to match disease activity. There is some evidence that this occurs spontaneously, even when using constitutive promoters. As long ago as 1999, Pan et al. (47,48) reported increased intra-articular transgene expression driven by a CMV promoter within an AAV vector during periods of high disease activity; expression fell as disease activity declined. Moreover, reactivation of disease caused re-stimulation of transgene expression. Traister et al. (79) reported something similar using human synovial fibroblasts transduced with AAV in vitro. Transgene expression was higher in the presence of recombinant inflammatory cytokines or synovial fluids recovered from inflamed, but not uninflamed, human joints. This occurred with both single-stranded and self-complementing vectors and was independent of the promoter that was used; the authors suggested enhanced intra-cellular trafficking as an explanation. Watson et al. (unpublished) have observed increased transgene expression in equine joints with OA, although the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon have not been explored. With IL1RN as the transgene, expression fell progressively to levels achieved in normal joints as disease activity subsided in response to the gene therapy.

Amplification of transgene expression in response to disease activity occurs through a different mechanism when integrating lentiviral vectors are used (46). Inflammation of the joint provokes synovial cell division, which replicates inserted viral genomes. Considerably elevated transgene expression is seen as a result (45).

Inducible promoters have been explored as a means of regulating transgene expression in joints. Although this can be achieved with TET system (73), most research has focused on the use of self-regulating promoters that respond to inflammatory stimuli within diseased joints, as first demonstrated by Maigkov et al. (80). An inducible promoter based upon a series of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) response elements is entering clinical trials in RA (49,81) (Table 1).

Selection of transgene

Unlike Mendelian disorders, complex diseases such as arthritis suggest no obvious or generally agreed therapeutic transgene. Clinical experience suggests that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 antagonists as well as immunosuppressive molecules successfully treat many patients with RA (82). However, there remains a large population of patients for whom such therapies are poorly effective. It has been suggested that interferon (IFN)-β could be usefully applied in such cases, and a gene therapy trial based on this premise is pending Phase I trials (49,81) (Table 1).

Recent studies have identified impaired inflammatory cell egress from joints as a result of lymphatic vessel damage and dysfunction as an important component of chronic inflammation in RA (83). Vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) promotes the formation and function of lymphatic vessels, providing an additional strategy for treatment. Using a murine model, Zhou et al. (84) confirmed the beneficial effect of injecting AAV encoding VEGF-C into joints with chronic inflammatory arthritis. A Phase I human clinical trial using adenovirus encoding VEGF-C in secondary lymphedema associated with the treatment of breast cancer is recruiting participants (NCT02994771).

An alternative approach to treating RA and other persistent inflammatory arthropathies involves reducing the size of the synovium, which in such diseases can be massively hypertrophic and hyperplastic. Such a strategy also promises to ameliorate arthrofibrosis (85) and pigmented villonodular synovitis (86), two conditions in which there is tissue overgrowth within the joint space. Traditionally, synovectomy has been accomplished surgically or by the injection of synoviocidal chemicals, including radionuclides. A non-surgical, genetic synovectomy offers an alternative way to debulk the synovium. Various strategies have shown promise in preclinical animal models, including the delivery of FasL (87,88), p53 (89), and herpes thymidine kinase in conjunction with ganciclovir (90). This approach only requires short-term transgene expression and does not need transduction of chondrocytes. However, a recent publication suggests that experimental OA in mice can be ameliorated by killing chondrocytes in the surface layer of cartilage (91). This finding is consistent with studies where agents that specifically kill senescent cells, termed “senolytics” (92), conferred therapeutic effects in animal models of OA (93). Whether the short-term symptomatic benefit of killing potentially senescent chondrocytes will be offset by delayed degenerative consequences of chondrocyte depletion remains to be seen.

There are no effective drugs for treating human OA, a complicated disease whose etiopathophysiology is poorly understood (94). Clinical medicine thus offers little help in identifying candidate therapeutic genes. Animal models of OA are also inadequate. General strategies for dealing with OA include combating inflammation, reducing pain, regenerating articular cartilage, and reversing boney changes, particularly subchondral sclerosis and the formation of osteophytes. Of these aims, the pain associated with OA represents an enormous unmet clinical need that has helped fuel the present epidemic of opioid addiction. No drug is able to slow the degeneration of joint structures, the elusive goal of a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD).

The authors' group has focused on blocking the intra-articular actions of IL-1 in OA by delivering the cDNA encoding IL-1Ra by ex vivo and in vivo approaches (27,95). Another, related protocol delivers TGF-β1 to joints with OA in an ex vivo fashion (33–35). Gene combinations are also of interest, and co-transduction of IL1RN with insulin-like growth factor-1 and IL-10 cDNAs has been studied experimentally (96–98). Improvements in transduction efficiency expand the scope of possible transgenes to include those encoding intra-cellular products, such as transcription factors (e.g., sox9), signaling molecules (e.g., IkB) and species of non-coding RNA (e.g., siRNAs).

Clinical trials

Tables 1 and 2 list human clinical trials for arthritis gene therapy that have taken place or, according to Clinicaltrials.gov, are pending.

The first clinical trial involved the ex vivo, retroviral delivery of IL1RN using autologous synovial fibroblasts (31). This Phase I study targeted the metacarpophalangeal joints of nine subjects with RA. A similar study in Germany dosed two subjects in this manner (32). Although the data confirmed the safety and feasibility of this method, with intra-articular expression of a biologically active transgene product, the approach was abandoned after a retrovirus with the same backbone (MFG) was used in an unrelated clinical trial where subjects developed leukemia (58). In addition, the ex vivo protocol using expanded, autologous synovial fibroblasts was found to be very expensive, tedious, and time-consuming. For these and other reasons, it was decided to change to an AAV vector, which permitted in vivo delivery of IL1RN cDNA.

During this period, powerful new drugs, including infliximab and etanercept, were introduced for the treatment of RA that reduced its attractiveness as a clinical target for a procedure as controversial as gene therapy. For this reason, a switch was made to OA as the target indication, where the patient population and unmet clinical need were considerably larger. The biological properties of IL-1 suggested it should be a good therapeutic target in OA, and preclinical experiments in animal models of OA bore this out (27,95).

The first of these used a canine, ACL-transection model in which ex vivo transfer of human IL-1Ra using autologous synovial fibroblasts protected cartilage from degeneration during the early stages of disease. This protective effect did not persist because transgene expression was lost after 2 weeks (27). Efficacy of IL-1Ra delivered in vivo using recombinant adenovirus was subsequently confirmed in an equine model of OA (95).

The safety of IL-1Ra gene therapy was suggested by an earlier study in which IL-1Ra was expressed systemically for life via the hematopoietic stem cells of mice (99). Following extensive pharmacology and toxicology testing (100), a self-complementing AAV vector, serotype 2.5, containing a codon-optimized human IL1RN cDNA under the transcriptional control of the CMV promoter was the subject of a successful IND application at the end of 2015. This dose-escalation clinical study will involve nine subjects with OA of the knee joint who will be followed for 1 year.

The first application of AAV in human joints delivered a cDNA encoding etanercept into the joints of patients with RA (56,57). Etanercept is a recombinant, fusion protein combining two TNF soluble receptors (p75) with the Fc domain of IgG1 (101). It blocks the actions of TNF, producing a dramatic clinical improvement in about 30–40% of patients. The recombinant protein, sold as the drug Enbrel, is delivered by intramuscular self-injection every 2 weeks; it was the third best-selling drug of 2016.

Despite the success of treating RA systemically with etanercept, there often remain symptomatic joints in this polyarticular disease after administering this drug. In response to this, AAV2 was used to deliver the etanercept cDNA to such joints, presumably with the assumption that insufficient etanercept entered these joints from the systemic circulation (see earlier discussion). Self-complementing virus could not be used because the cDNA encoding etanercept is too large.

A Phase I study involving 14 subjects with RA and one with ankylosing spondylitis proceeded uneventfully, with some evidence of a clinical response (57) However, a subject died during a subsequent Phase II trial involving 127 subjects (56). The details of this case have been described extensively (102,103). Investigations were conducted by the Regulatory Affairs Certification and Food and Drug Administration, after which the trial was allowed to continue with some minor changes to the protocol and consent form. There has been no subsequent development of this protocol.

In the latest trial for the gene therapy of RA, AAV5 will be used to deliver IFN-β cDNA to symptomatic joints (Table 1). The vector is self-complementing, and the transgene is under the transcriptional control of NF-κB response elements, so expression should be induced by flares and remain at low levels when inflammation subsides. Extensive testing has confirmed the safety of this construct (49,81), and the trial has begun recruiting patients.

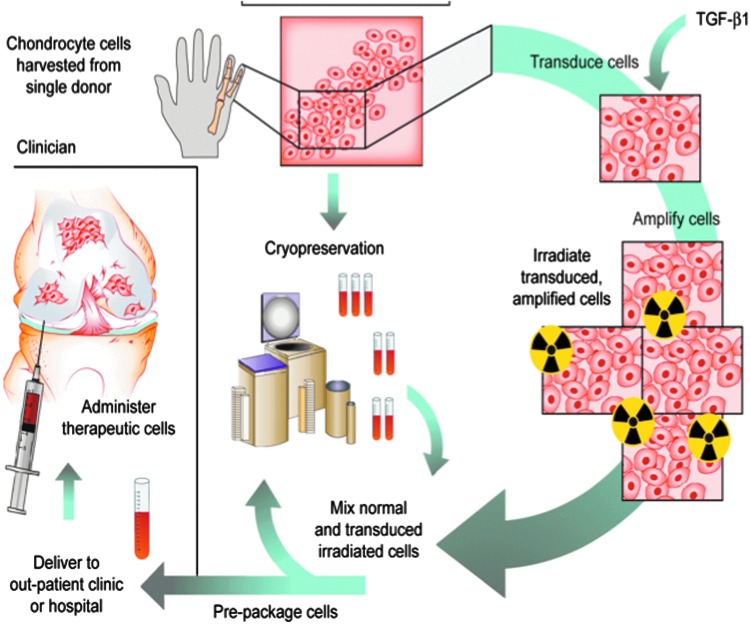

Only one arthritis gene therapy protocol has advanced to Phase III trials. This is an ex vivo protocol using an established line of chondrocytes derived from an infant with polydactyly (33–35). One line of these cells was transduced with a retrovirus carrying TGF-β1 cDNA under the control of a CMV promoter. To eliminate the possibility of malignant transformation, before injection, the cells, which carrying multiple copies of the TGF-β1 retrovirus, are irradiated at doses that prevent cell division but permit the continued synthesis and secretion of high levels of TGF-β1. To amplify and extend the effects of TGF-β1, an auto-inductive protein, the irradiated cells are mixed in a 1:3 ratio with untransduced, unirradiated cells of the same origin before injection into the joint (Fig. 4); 3 × 107 cells are injected per knee. This procedure improves pain and function scores in the knee joints of patients with OA. The product is known as Invossa™, and a Biologics License Application was recently approved in Korea, making it only the fifth gene therapy product in the world, and the second using ex vivo delivery to gain marketing approval (Table 3). Invossa™ was approved for injection into knee joints with moderate OA that has failed standard pharmacologic and physical therapy. It was not given DMOAD designation. A Phase III trial of Invossa™ in the United States is expected to begin shortly.

Figure 4.

Human gene therapy protocol for Invossa™. Chondrocytes were harvested from an infant with polydactyly. One line of cells was retrovirally transduced to express TGF-β1. Before use, the genetically modified cells are irradiated and mixed with unmodified chondrocytes from the same donor prior to injection into the joint.

Table 3.

Approved gene therapies worldwide

| Indication | Vector | Gene | Name | Place | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | Adenovirus | p53 | Gendicine | PR China | 2003 |

| Lipoprotein lipase deficiency | AAV | Lipoprotein lipase | Glybera | Europe | 2012 |

| Melanoma | Herpes simplex virus | Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor | Imlygic | United States | 2015 |

| Adenosine deaminase deficiency | Retrovirus | Adenosine deaminase | Strimvalis | Europe | 2016 |

| Osteoarthritis | Retrovirus | Transforming growth factor-β1 | Invossa | Korea | 2017 (July) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Lentivirus | Chimeric antigen receptor | Kymriah | United States | 2017 (August) |

Summary and Conclusions

Gene transfer provides a way to overcome the problem of delivering biologics to joints in a focal, local, sustained, and efficient manner. This capability offers new ways to address some of the most common, debilitating, and intractable conditions of modern medicine. Although gene therapy for arthritis and related conditions has been discussed for >25 years, progress toward clinical application has been slow. Nevertheless, there have been several clinical trials, and the first product, Invossa™, has just received marketing approval in Korea. Phase III human clinical trials of Invossa™ are projected to begin shortly in the United States. Its approval should stimulate interest in the entire field leading to more rapid development of genetic drugs for conditions that affect joints.

Acknowledgments

The authors' work in this area has been supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AR43623, R21 AR049606, R01 AR048566, R01 AR057422, and R01 AR051085), DoD (grant W81XWH-16-1-0540), and Orthogen AG.

Author Disclosure

C.H.E. and P.D.R. are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of TissueGene, Inc. C.H.E., S.C.G., and P.D.R. are co-founders of Genascence, Inc.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotlarz H, Gunnarsson CL, Fang H, et al. Insurer and out-of-pocket costs of osteoarthritis in the US: evidence from national survey data. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3546–3553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin J, Theis KA, Barbour KE, et al. Impact of arthritis and multiple chronic conditions on selected life domains—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:578–582 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD. Arthritis gene therapy and its tortuous path into the clinic. Transl Res 2013;161:205–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD. Getting arthritis gene therapy into the clinic. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:244–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD. Arthritis gene therapy: a brief history and perspective. In: Laurence J, Franklin A, eds. Translating Gene Therapy into the Clinic. New York: Elsevier, 2015:85–98 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowthwaite GP, Bishop JC, Redman SN, et al. The surface of articular cartilage contains a progenitor cell population. J Cell Sci 2004;117:889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong W, Geng Y, Huang Y, et al. In vivo identification and induction of articular cartilage stem cells by inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling in osteoarthritis. Stem Cells 2015;33:3125–3137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becerra J, Andrades JA, Guerado E, et al. Articular cartilage: structure and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2010;16:617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makris EA, Hadidi P, Athanasiou KA. The knee meniscus: structure–function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials 2011;32:7411–7431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negahi Shirazi A, Chrzanowski W, Khademhosseini A, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament: structure, injuries and regenerative treatments. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015;881:161–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burda B, Steidle-Kloc E, Dannhauer T, et al. Variance in infra-patellar fat pad volume: does the body mass index matter?—Data from osteoarthritis initiative participants without symptoms or signs of knee disease. Ann Anat 2017;213:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwanaga T, Shikichi MKitamura H, et al. Morphology and functional roles of synoviocytes in the joint. Arch Histol Cytol 2000;63:17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Sousa EB, Casado PL, Moura Neto V, et al. Synovial fluid and synovial membrane mesenchymal stem cells: latest discoveries and therapeutic perspectives. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014;5:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu H, Edwards J, Banerji S, et al. Distribution of lymphatic vessels in normal and arthritic human synovial tissues. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1227–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Firestein GS, Budd R, Gabriel SE, et al. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. 9th ed. New York: Saunders, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans CH, Kraus VB, Setton LA. Progress in intra-articular therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:11–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandara G, Robbins PD, Georgescu HI, et al. Gene transfer to synoviocytes: prospects for gene treatment of arthritis. DNA Cell Biol 1992;11:227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auclair D, Hopwood JJ, Lemontt JF, et al. Long-term intra-articular administration of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase in feline mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Mol Genet Metab 2007;91:352–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers S, Rothe M, Lalic J, et al. Lentiviral-mediated correction of MPS VI cells and gene transfer to joint tissues. Mol Genet Metab 2009;97:102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Hakobyan N, Valentino LA, et al. Intraarticular Factor IX protein or gene replacement protects against development of hemophilic synovitis in the absence of circulating Factor IX. Blood 2008;112:4532–4541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans CH, Huard J. Gene therapy approaches to regenerating the musculoskeletal system. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:234–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makarov SS, Olsen JC, Johnston WN, et al. Suppression of experimental arthritis by gene transfer of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:402–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Lechman ER, Kim S, et al. Ex vivo gene delivery of IL-1Ra and soluble TNF receptor confers a distal synergistic therapeutic effect in antigen-induced arthritis. Mol Ther 2002;6:591–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Mao Z, Yu C. Suppression of early experimental osteoarthritis by gene transfer of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and interleukin-10. J Orthop Res 2004;22:742–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandara G, Mueller GM, Galea-Lauri J, et al. Intraarticular expression of biologically active interleukin 1-receptor-antagonist protein by ex vivo gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993;90:10764–10768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelletier JP, Caron JP, Evans C, et al. In vivo suppression of early experimental osteoarthritis by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist using gene therapy. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1012–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armbruster N, Weber C, Wictorowicz T, et al. Ex vivo gene delivery to synovium using foamy viral vectors. J Gene Med 2014;16:166–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day CS, Kasemkijwattana C, Menetrey J, et al. Myoblast-mediated gene transfer to the joint. J Orthop Res 1997;15:894–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelse K, Jiang QJ, Aigner T, et al. Fibroblast-mediated delivery of growth factor complementary DNA into mouse joints induces chondrogenesis but avoids the disadvantages of direct viral gene transfer. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1943–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans CH, Robbins PD, Ghivizzani SC, et al. Gene transfer to human joints: progress toward a gene therapy of arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:8698–8703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehling P, Reinecke J, Baltzer AW, et al. Clinical responses to gene therapy in joints of two subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Gene Ther 2009;20:97–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ha CW, Cho JJ, Elmallah RK, et al. A multicenter, single-blind, Phase IIa clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a cell-mediated gene therapy in degenerative knee arthritis patients. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2015;26:125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ha CW, Noh MJ, Choi KB, et al. Initial Phase I safety of retrovirally transduced human chondrocytes expressing transforming growth factor-beta-1 in degenerative arthritis patients. Cytotherapy 2012;14:247–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherian JJ, Parvizi J, Bramlet D, et al. Preliminary results of a Phase II randomized study to determine the efficacy and safety of genetically engineered allogeneic human chondrocytes expressing TGF-beta1 in patients with grade 3 chronic degenerative joint disease of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:2109–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roessler BJ, Allen ED, Wilson JM, et al. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to rabbit synovium in vivo. J Clin Invest 1993;92:1085–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nita I, Ghivizzani SC, Galea-Lauri J, et al. Direct gene delivery to synovium. An evaluation of potential vectors in vitro and in vivo. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:820–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe S, Imagawa T, Boivin GP, et al. Adeno-associated virus mediates long-term gene transfer and delivery of chondroprotective IL-4 to murine synovium. Mol Ther 2000;2:147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruan MZ, Erez A, Guse K, et al. Proteoglycan 4 expression protects against the development of osteoarthritis. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:176ra134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghivizzani SC, Lechman ER, Tio C, et al. Direct retrovirus-mediated gene transfer to the synovium of the rabbit knee: implications for arthritis gene therapy. Gene Ther 1997;4:977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oligino T, Ghivizzani S, Wolfe D, et al. Intra-articular delivery of a herpes simplex virus IL-1Ra gene vector reduces inflammation in a rabbit model of arthritis. Gene Ther 1999;6:1713–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans C, Goins WF, Schmidt MC, et al. Progress in development of herpes simplex virus gene vectors for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1997;27:41–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu S, Kiyoi T, Takemasa E, et al. Intra-articular lentivirus-mediated gene therapy targeting CRACM1 for the treatment of collagen-induced arthritis. J Pharmacol Sci 2017;133:130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen SY, Shiau AL, Li YT, et al. Suppression of collagen-induced arthritis by intra-articular lentiviral vector-mediated delivery of Toll-like receptor 7 short hairpin RNA gene. Gene Ther 2012;19:752–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gouze E, Pawliuk R, Gouze JN, et al. Lentiviral-mediated gene delivery to synovium: potent intra-articular expression with amplification by inflammation. Mol Ther 2003;7:460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gouze E, Pawliuk R, Pilapil C, et al. In vivo gene delivery to synovium by lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther 2002;5:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan RY, Xiao X, Chen SL, et al. Disease-inducible transgene expression from a recombinant adeno-associated virus vector in a rat arthritis model. J Virol 1999;73:3410–3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan RY, Chen SL, Xiao X, et al. Therapy and prevention of arthritis by recombinant adeno-associated virus vector with delivery of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bevaart L, Aalbers CJ, Vierboom MP, et al. Safety, biodistribution, and efficacy of an AAV-5 vector encoding human interferon-beta (ART-I02) delivered via intra-articular injection in rhesus monkeys with collagen-induced arthritis. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2015;26:103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson RS, Broome TA, Levings PP, et al. scAAV-mediated gene transfer of interleukin-1-receptor antagonist to synovium and articular cartilage in large mammalian joints. Gene Ther 2013;20:670–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kay JD, Gouze E, Oligino TJ, et al. Intra-articular gene delivery and expression of interleukin-1Ra mediated by self-complementary adeno-associated virus. J Gene Med 2009;11:605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Apparailly F, Khoury M, Vervoordeldonk MJ, et al. Adeno-associated virus pseudotype 5 vector improves gene transfer in arthritic joints. Hum Gene Ther 2005;16:426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang HG, Xie J, Yang P, et al. Adeno-associated virus production of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor neutralizes tumor necrosis factor alpha and reduces arthritis. Hum Gene Ther 2000;11:2431–2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goater J, Muller R, Kollias G, et al. Empirical advantages of adeno associated viral vectors in vivo gene therapy for arthritis. J Rheumatol 2000;27:983–989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evans CH, Gouze E, Gouze JN, et al. Gene therapeutic approaches—transfer in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2006;58:243–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mease PJ, Wei N, Fudman EJ, et al. Safety, tolerability, and clinical outcomes after intraarticular injection of a recombinant adeno-associated vector containing a tumor necrosis factor antagonist gene: results of a Phase 1/2 study. J Rheumatol 2010;37:692–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mease PJ, Hobbs K, Chalmers A, et al. Local delivery of a recombinant adenoassociated vector containing a tumour necrosis factor alpha antagonist gene in inflammatory arthritis: a Phase 1 dose-escalation safety and tolerability study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1247–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science 2003;302:415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.ter Huurne M, Schelbergen R, Blattes R, et al. Antiinflammatory and chondroprotective effects of intraarticular injection of adipose-derived stem cells in experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3604–3613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horie M, Choi H, Lee RH, et al. Intra-articular injection of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) promote rat meniscal regeneration by being activated to express Indian hedgehog that enhances expression of type II collagen. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20:1197–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozeki N, Muneta T, Koga H, et al. Not single but periodic injections of synovial mesenchymal stem cells maintain viable cells in knees and inhibit osteoarthritis progression in rats. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1061–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hemphill DD, McIlwraith CW, Samulski RJ, et al. Adeno-associated viral vectors show serotype specific transduction of equine joint tissue explants and cultured monolayers. Sci Rep 2014;4:5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodrich LR, Choi VW, Carbone BA, et al. Ex vivo serotype-specific transduction of equine joint tissue by self-complementary adeno-associated viral vectors. Hum Gene Ther 2009;20:1697–1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodrich LR, Phillips JN, McIlwraith CW, et al. Optimization of scAAVIL-1ra in vitro and in vivo to deliver high levels of therapeutic protein for treatment of osteoarthritis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2013;2:e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boissier MC, Lemeiter D, Clavel C, et al. Synoviocyte infection with adeno-associated virus (AAV) is neutralized by human synovial fluid from arthritis patients and depends on AAV serotype. Hum Gene Ther 2007;18:525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cottard V, Valvason C, Falgarone G, et al. Immune response against gene therapy vectors: influence of synovial fluid on adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer to chondrocytes. J Clin Immunol 2004;24:162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goodrich LR, Grieger JC, Phillips JN, et al. scAAVIL-1ra dosing trial in a large animal model and validation of long-term expression with repeat administration for osteoarthritis therapy. Gene Ther 2015;22:536–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mingozzi F, Chen Y, Edmonson SC, et al. Prevalence and pharmacological modulation of humoral immunity to AAV vectors in gene transfer to synovial tissue. Gene Ther 2013;20:417–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ertl HCJ, High KA. Impact of AAV capsid-specific T-cell responses on design and outcome of clinical gene transfer trials with recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors: an evolving controversy. Hum Gene Ther 2017;28:328–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katakura S, Jennings K, Watanabe S, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus preferentially transduces human, compared to mouse, synovium: implications for arthritis therapy. Mod Rheumatol 2004;14:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kyostio-Moore S, Bangari DS, Ewing P, et al. Local gene delivery of heme oxygenase-1 by adeno-associated virus into osteoarthritic mouse joints exhibiting synovial oxidative stress. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:358–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ulrich-Vinther M, Duch MR, Soballe K, et al. In vivo gene delivery to articular chondrocytes mediated by an adeno-associated virus vector. J Orthop Res 2004;22:726–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee HH, O'Malley MJ, Friel NA, et al. Persistence, localization, and external control of transgene expression after single injection of adeno-associated virus into injured joints. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:457–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madry H, Cucchiarini M, Terwilliger EF, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors efficiently and persistently transduce chondrocytes in normal and osteoarthritic human articular cartilage. Hum Gene Ther 2003;14:393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ulrich-Vinther M, Maloney MD, Goater JJ, et al. Light-activated gene transduction enhances adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene expression in human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2095–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bajpayee AG, Wong CR, Bawendi MG, et al. Avidin as a model for charge driven transport into cartilage and drug delivery for treating early stage post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Biomaterials 2014;35:538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aalbers CJ, Broekstra N, van Geldorp M, et al. Empty capsids and macrophage inhibition/depletion increase rAAV transgene expression in joints of both healthy and arthritic mice. Hum Gene Ther 2017;28:168–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gouze E, Gouze JN, Palmer GD, et al. Transgene persistence and cell turnover in the diarthrodial joint: implications for gene therapy of chronic joint diseases. Mol Ther 2007;15:1114–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Traister RS, Fabre S, Wang Z, et al. Inflammatory cytokine regulation of transgene expression in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes infected with adeno-associated virus. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2119–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miagkov AV, Varley AW, Munford RS, et al. Endogenous regulation of a therapeutic transgene restores homeostasis in arthritic joints. J Clin Invest 2002;109:1223–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aalbers CJ, Bevaart L, Loiler S, et al. Preclinical potency and biodistribution studies of an AAV 5 vector expressing human interferon-beta (ART-I02) for local treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bouta EM, Li J, Ju Y, et al. The role of the lymphatic system in inflammatory-erosive arthritis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015;38:90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou Q, Guo R, Wood R, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C attenuates joint damage in chronic inflammatory arthritis by accelerating local lymphatic drainage in mice. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:2318–2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Magit D, Wolff A, Sutton K, et al. Arthrofibrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007;15:682–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tyler WK, Vidal AF, Williams RJ, et al. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14:376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang H, Gao G, Clayburne G, et al. Elimination of rheumatoid synovium in situ using a Fas ligand “gene scalpel.” Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R1235–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yao Q, Glorioso JC, Evans CH, et al. Adenoviral mediated delivery of FAS ligand to arthritic joints causes extensive apoptosis in the synovial lining. J Gene Med 2000;2:210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao Q, Wang S, Glorioso JC, et al. Gene transfer of p53 to arthritic joints stimulates synovial apoptosis and inhibits inflammation. Mol Ther 2001;3:901–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goossens PH, Schouten GJ, ’t Hart BA, et al. Feasibility of adenovirus-mediated nonsurgical synovectomy in collagen-induced arthritis-affected rhesus monkeys. Hum Gene Ther 1999;10:1139–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang M, Mani SB, He Y, et al. Induced superficial chondrocyte death reduces catabolic cartilage damage in murine posttraumatic osteoarthritis. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2893–2902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015;14:644–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jeon OH, Kim C, Laberge RM, et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat Med 2017;23:775–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM, et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Frisbie DD, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD, et al. Treatment of experimental equine osteoarthritis by in vivo delivery of the equine interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene. Gene Ther 2002;9:12–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Haupt JL, Frisbie DD, McIlwraith CW, et al. Dual transduction of insulin-like growth factor-I and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein controls cartilage degradation in an osteoarthritic culture model. J Orthop Res 2005;23:118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nixon AJ, Haupt JL, Frisbie DD, et al. Gene-mediated restoration of cartilage matrix by combination insulin-like growth factor-I/interleukin-1 receptor antagonist therapy. Gene Ther 2005;12:177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Neumann E, Judex M, Kullmann F, et al. Inhibition of cartilage destruction by double gene transfer of IL-1Ra and IL-10 involves the activin pathway. Gene Ther 2002;9:1508–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Boggs SS, Patrene KD, Mueller GM, et al. Prolonged systemic expression of human IL-1 receptor antagonist (hIL-1ra) in mice reconstituted with hematopoietic cells transduced with a retrovirus carrying the hIL-1ra cDNA. Gene Ther 1995;2:632–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang G, Evans CH, Benson JM, et al. Safety and biodistribution assessment of sc-rAAV2.5IL-1Ra administered via intra-articular injection in a mono-iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis rat model. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2016;3:15052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Scott LJ. Etanercept: a review of its use in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Drugs 2014;74:1379–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Evans CH, Ghivizzani SC, Robbins PD. Arthritis gene therapy's first death. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Frank KM, Hogarth DK, Miller JL, et al. Investigation of the cause of death in a gene-therapy trial. N Engl J Med 2009;361:161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]