Summary

A great variety of cell imaging technologies are used routinely every day for the investigation of kidney cell types in applications ranging from basic science research to drug development and pharmacology, clinical nephrology and pathology. Quantitative visualization of the identity, density and fate of both resident and non-resident cells in the kidney, and imaging-based analysis of their altered function, (patho)biology, metabolism, signaling in disease conditions can help to better define pathomechanism-based disease subgroups, identify critical cells and structures that play a role in the pathogenesis, critically needed biomarkers of disease progression, and cell and molecular pathways as targets for novel therapies. Overall, renal cell imaging has great potential for improving the precision of diagnostic and treatment paradigms for individual acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients or patient populations. This review highlights and provides examples for some of the recently developed renal cell optical imaging approaches, mainly intravital multiphoton fluorescence microscopy, and the new knowledge they provided for our better understanding of renal pathologies.

Keywords: Genetic cell fate tracking, ischemia reperfusion injury, cell metabolism, calcium signaling, multiplex imaging, fibrosis

The currently used applications and further development of highly innovative future next-generation cell and tissue imaging technologies using novel, multiplexed fluorescence as well as label-free, nondestructive microscopy techniques are essential for the highly precise quantitative and automated (unbiased) analysis of kidney structure and function. These include both research and clinical uses of the living or fixed kidney tissue, and are especially relevant and important for the single cell-level investigation of human renal nephrectomy and biopsy specimen. The need for high precision cellular imaging as a diagnostic tool, along with the use of molecular-level omics approaches, is well justified by the recognition of individual variability in the cellular and molecular pathomechanism of human diseases including AKI and CKD.1, 2 In fact, the National Institute of Health (NIH) has recently launched its precision medicine initiative3 that focuses on accelerating the development of individualized, cell and molecular mechanism-based targeted treatments for not only cancer but other diseases as well. The translation of this initiative, and the already ongoig efforts in the renal field are well illustrated by the most recent birth of the Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP) funded and overseen by the NIH/NIDDK.4 Advanced renal cell imaging will be a key part in the KPMP which aims to create a kidney tissue atlas, define disease subgroups, and identify critical cells, pathways, and targets for novel therapies.4 For example, detailed analysis of the spatial distribution of single cell states by highly multiplexed single cell and molecular imaging with subcellular and 3D resolution will be essential for building a kidney tissue atlas for future data mining and new therapeutic and biomarker development.

Next generation imaging techniques set their foundation on current renal cell imaging approaches. Optical imaging techniques, including multiphoton microscopy (MPM), have been used and perfected throughout decades for the detailed and quantitative imaging of kidney structure and function.5–9 Due to its sub-micron resolution and harmless, deep tissue imaging capability,10–12 MPM is ideally suited to perform renal cell imaging in the intact living kidney in vivo, or large volumes of fixed kidney tissue. Applications of MPM combined with tissue clearing techniques of the human kidney demonstrated diagnostic-level image quality that can be maintained through 1 millimeter of tissue, and therefore have great potential for increasing the yield of histologic evaluation of biopsy specimens.13 Similar approaches are expected to be instrumental also for the efforts of the KPMP to build a kidney tissue atlas.4 For intravital applications, MPM has solved a long-standing critical technical barrier in renal research to study several complex and inaccessible cell types (for example the podocyte) and anatomical structures (such as the glomerular filtration barrier) in vivo in their native environment.14–17 Various modalities for the quantitative MPM imaging of the basic parameters of kidney function (e.g. single nephron glomerular filtration rate (snGFR), blood flow, tubular fluid flow, glomerular albumin leakage and tubular uptake, the inra-renal renin-angiotensin system, etc) have been reported and reviewed elsewhere.11, 18–24 Refinements of these techniques including successful fiberoptic delivery of photons and minimally invasive intravital endomicroscopy of the kidney may one day lead to human clinical diagnostic applications.25

This paper focuses on renal cell imaging, highlighting recent advances in the quantitative visualization of the identity, density and fate of both resident and non-resident cells in the kidney, and imaging-based analysis of their altered function, (patho)biology, metabolism, signaling in both the rodent (research applications) as well as the human kidney (clinical diagnostic and translational applications). We review some of the recently developed renal cell optical imaging approaches and also provide practical examples with supporting new preliminary data for their potential applications, advantages, feasibility, and promise in further improving our understanding of kidney disease mechanisms and developing new therapeutic and diagnostic applications with the principle of kidney precision medicine.

Single cell and cell lineage identification and fate tracking

The precise identification and analysis of resident and non-resident renal cell types within kidney tissue specimen are essential for studying disease pathobiology, histology, cell-to-cell interactions, therapeutic effects of drugs, in clinical differential diagnostics, etc. Genetic labeling of renal cell types using fluorescent lineage tags, and genetic cell fate tracking in animal models provided highly specific, positive identification of several renal cell types and their fate changes. For example, cell-specific promoter-driven expression of monochromatic (e.g. the green fluorescent protein GFP) or multi-color fluorescent tags (e.g. the two-color membrane-targeted tandem dimer Tomato or GFP (mT/mG)26 and the four-color Confetti construct of cyan, green, yellow, and red fluorescent proteins (CFP/GFP/YFP/RFP))27 allowed the precise identification of glomerular cells including podocytes and parietal epithelial cells (PECs) in both mouse14, 16, 28–31 and zebrafish models.15, 32 The use of these and similar cell identification research tools for genetic cell fate tracking purposes provided evidence for the presence of both motile and stationary podocytes and PECs,14–16, 31–33 podocyte clustering and migration to the parietal Bowman’s capsule,16, 34, 35 and the recruitment of podocytes from PECs.28, 33, 36 In general, these studies captured the highly dynamic nature of cellular remodeling of the glomerular environment especially under glomerular injury conditions including atubular glomeruli, unilateral ureteral obstruction, and the Adriamycin nephropathy and cytotoxic IgG-induced podocyte injury models of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).16, 17, 28, 33–36 In addition, the combination of multi-color genetic cell identification and fate tracking with serial MPM imaging of the same glomeruli in the same kidney and animal over several days is the only currently available technique that allows the investigation of the migration pattern and dynamics of the same single renal cells in the intact living kidney.11, 16, 21, 34, 37, 38 This approach has great potential for the unbiased study of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of endogenous tissue remodeling and repair after injury. Genetic cell fate tracking tools and approaches have been described for several developmental or injury-related renal progenitor cell populations and their lineages to study kidney regeneration, including glomerular epithelial cells (e.g. Pax2 lineage),28 proximal tubule cells (e.g. Six2 and Sox9),39–41 the distal nephron (e.g. Lgr5),42 and collecting ducts (e.g. Aqp2, Slc12a3 and p63).43, 44 Also, many different cell compartments of the renal interstitium and vasculature have been studied using similar tools including pericytes (e.g. Foxd1, Coll1a1, Gli1 lineage),45–48 vascular endothelial cells (e.g. Tie2),21, 49 and cells of the renin lineage (e.g. Ren1d, Ren1c).38, 50

In Fig. 1 we show examples of intravital MPM imaging of less commonly studied renal cell types and genetic models. Multi-color labeling of cells of the renin lineage can identify individual cells of the classic vascular site (juxtaglomerular apparatus) as well as the novel tubular site of renin production in the connecting tubule-collecting duct system (Fig. 1A–C), consistent with earlier descriptions of renin expression and renin cell distribution.51, 52 The presence of cell labeling in the Bowman’s capsule and glomerular mesangium (Fig. 1A–B) is in agreement with the findings that cells of the renin lineage are adult pluripotent progenitors that function as precursors of PECs and podocytes,50, 53 and that cell neogenesis repopulates progenitor renin lineage cells in the kidney.37 The use of the multi-color Confetti reporter can provide the additional technical capability to address the migration dynamics, pattern, and clonality features of single progenitor cell-mediated tissue remodeling.38 The strong expression of fluorescent reporters also provided new technical capabilities for optical microscopy in studying the ultrastructural detail of renal cell types. Quantitative measurements of podocyte foot processes,54 which have been traditionally studied using electron microscopy55 is a good example. In addition, intravital MPM identified the presence of nanotubes in the Bowman’s space interconnecting single PECs and podocytes (Fig. 1B)16 which may play a role in cell migration and/or in the exchange of material between these cell types.16 Cells of the proximal tubule can be labeled using several genetic strategies including γGT-mTmG mice (Fig. 1D) which can be developed using available tools.56 This approach results in heterogenous, segmental rather than continuous epithelial cell labeling which may reflect segmental differences in Cre activity (mTmG expression), cell function, metabolism or remodeling. Another renal cell type that is subject of intense study is the interstitial pericyte which can be genetically labeled using the Coll1a1-GFP mouse model (Fig. 1E) among others.45–48 Intravital MPM was used to visualize pericytes concentrated at areas of branching points in the microvascular network, their long processes around proximal tubule cells and peritubular capillaries (Fig. 1E), and their many functions that help maintain renal vascular integrity.47 Lymphatic endothelial cells (Fig. 1F) can also be labeled using the Prox1-GFP mouse model that was developed recently.57, 58 Intravital MPM imaging can be used to study the plasticity, branching, and functional features of lymphatic vessels in the renal cortex, as exemplified in Fig. 1F using a Prox1-GFP mouse kidney 21 days after unilateral ureter obstruction (UUO) and previously established MPM techniques.16

Figure 1. Intravital MPM imaging of renal cell types and lineages in the mouse kidney cortex based on genetic cell identification and fate tracking.

A–C: Individual cells of the renin lineage are labeled in Ren1d-Confetti mouse kidneys in one of four colors (membrane-targeted CFP, nuclear GFP, cytosolic YFP or cytosolic RFP), and identify the classical vascular site of intra-renal renin synthesis in the juxtaglomerular apparatus around the terminal afferent arteriole (AA), but not the efferent arteriole (EA, panel A). Cells of the Bowman’s capsule around glomeruli (G, panels A–B) and the tubular site of renin production in two connecting tubule segments (CNT1-2) merging into the common cortical collecting duct (CCD, panel C) are also labeled. B: Nanotubes (arrows) are visible interconnecting the cells of the parietal and visceral Bowman’s capsule over the open filtration space. D: Proximal tubule segments (green) are labeled in γGT-mTmG mice. Note the fragmented rather than continuous epithelial cell labeling (arrows). E: Interstitial pericytes (green) are labeled in Coll1a1-GFP mice, and are visible around the proximal tubule (PT) peritubular capillaries. F: Lymphatic endothelial cells (green) are labeled in Prox1-GFP mouse kidney. Note the branching lymphatic vessels (arrows) in a mouse kidney 21 days after unilateral ureter obstruction (UUO). In all images plasma was labeled red using Albumin-Alexa594. Bar is 50 μm.

In addition to non-specific, negative cell labeling techniques,17 and the above detailed genetic strategies, specific single cells in the kidney can be positively identified and then tracked based on their unique cell surface markers. Perhaps the best example is the many different types of immune cells homing to distinct parts of the renal vasculature and interstitium in response to injury. Fig. 2 illustrates an example of potential uses of quantitative intravital MPM imaging for studying the changes in renal cortical CD44+ cell density after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), a commonly used model of AKI. In these original experiments, renal ischemia was induced in C57BL6/J mice (5–6 weeks old male, wild type mice from our colony, protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California) after right nephrectomy by clipping the renal pedicle of the remaining left kidney for 20 minutes. Endogenous CD44+ cells were labeled by iv injection of Alexa488-conjugated anti-CD44 antibodies (and in some experiments Alexa594-conjugated anti-CD3 antibodies that together identified T lymphocites, not shown), and intravital MPM was performed using techniques as described before.16, 59, 60 At baseline, only a few circulating CD44-positive cells were found that were occasionally retained in capillaries for only a few seconds (Fig. 2A, and Supplementary movie 1). In contrast, MPM imaging of the same kidneys 1–2 days after IRI found a significantly increased, almost 10-fold higher number of CD44+ cells homing (stationary or slowly migrating) in peritubular capillaries surrounding proximal tubule segments (Fig. 2B–D, and Supplementary movie 2). These results are consistent with the well-established roles of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions in both proinflammatory immune cells as well as in regenerative cell types and processes in renal IRI injury.61–64 More specific identification of immune cell subtypes, and MPM imaging of their recruitment, behavior, cell-to-cell and endothelial glycocalyx65 interactions in different areas of the renal microcirculation can help improve our understanding of the inflammatory processes not only in the AKI model IRI, but also in many other kidney diseases. Similar immune cell labeling and tracking techniques, including in vivo MPM imaging applications have been used to label monocytes, dendritic cells, neutrophils,59, 60, 66 and revealed a new leukocyte recruitment paradigm in the glomerulus, suggesting that the major effect of acute inflammation is to increase the duration of leukocyte retention.59 Other immune cells, for example macrophages and T and B lymphocytes that play well established roles in AKI67, 68 can be potentially studied in the future using similar cell labeling and tracking techniques. Establishing specific immune cell signatures during different phases of AKI and other inflammatory kidney diseases has great potential to improve our ability to discern the most important markers of renal injury and repair, that may identify at risk patients. When applying these approaches to the human renal biopsy, and linked to clinical data, immune cell imaging results may help define disease pathophysiology, stratify AKI and CKD disease subgroups, predict clinical outcome and identify potential tailored therapeutic targets for AKI and CKD, all essential elements of the successful development of personalized medicine for kidney diseases.

Figure 2. Quantitative intravital MPM imaging of the changes in renal cortical CD44+ cell density after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI).

A: Control, non-ischemic images were obtained at baseline (Pre-IRI) after labeling endogenous CD44+ cells by iv injection of Alexa488-conjugated anti-CD44 antibody (green). Plasma was labeled red using Albumin-Alexa594. Note the intense autofluorescence in proximal (PT) but not in distal tubule (DT) segments owing to the high density of NADH-rich mitochondria, and the low number of circulating CD44+ cells (arrows, magnified in insets). Bar is 20 μm. B–C: MPM images of the mouse renal cortex 1 (B) and 2 (C) days after IRI. Note the high number of CD44+ cells homing in peritubular capillaries surrounding PT segments. D: Statistical summary of the density of CD44+ cells in the renal cortex before and after IRI. CD44+ cell numbers were counted per microscope field. *p<0.05, n=4 each.

Imaging cell (patho)biology, signaling, and metabolism

In addition to imaging single renal cell types and their migration and fate changes, several parameters of basic cell biology can be quantitatively visualized using imaging techniques. Due to its relevance in various organ pathologies including kidney disease, several imaging tools have been developed to study the many forms of cell death. This was the topic of a recent issue of Seminars in Nephrology, and therefore imaging cell death is discussed in great detail there.22

Recently, several fluorescent markers of cell cycle stage have been developed that allow estimation of cell cycle dynamics. The Fucci system incorporates genetically encoded probes that highlight G1 and S/G2/M phases of the cell cycle allowing live imaging. The latest refinement is the Fucci2a system and the R26Fucci2aR mouse model that feature a bicistronic cell cycle reporter and allow Cre-mediated tissue specific expression in mice.69 These are truly exciting and compelling new tools for the investigation of cell cycle dynamics in vivo, have been applied to studying kidney development,69 and will be undoubtedly used in many future research applications in mouse models of kidney disease.

Endocytosis in renal cells, especially albumin uptake, processing, and transcytosis of filtered albumin by cells of the proximal tubule have been studied in great detail using in vivo MPM imaging, including the elements of a reclamation pathway that minimizes urinary loss and catabolism of albumin, therefore prolonging its serum half-life.70 Under different albumin loading conditions, a complex molecular regulatory system was identified that responded rapidly to different physiologic conditions to minimize alterations in serum albumin levels.71 Most recently, proximal tubule albumin uptake was studied in a rat model of salt-sensitive hypertension, which was found to be associated with progressive pathogenic remodeling of proximal tubule epithelia, and changes in albumin handling. 72 Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a well established role in the pathogenesis of AKI, yet it has been poorly understood. In his pioneering work, Hall et al studied mitochondrial structure and function, and cell metabolism of renal cell types using intravital imaging, along with the relevant aerobic and anaerobic metabolic pathways of both proximal and distal tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury.10, 18, 73 Using both endogenous (e.g. NAD) and exogenous fluorophores (e.g. the mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent dye TMRM injected iv), marked increases in NAD, and rapid dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential were found in response to ischemia in proximal but not in distal tubule segments consistent with the vulnerability of proximal tubule epithelial cells in AKI.73 Here we show examples of intravital MPM imaging of the changes in cell metabolism in the living mouse kidney in response to a short interval of ischemia. Quantitative, time-lapse measurements of the mitochondrial membrane potential in the same glomerulus and surrounding tubule segments were performed before and and after 10 min of IRI (Fig. 3), using iv injected MitoTracker-Red and MPM imaging techniques as described before.8, 19, 73 Although proximal tubule cells showed a transient increase in MitoTracker-Red fluorescence after this short interval of ischemia (Fig. 3A–D), the highest fluorescence intensity was observed in podocytes and in the distal tubule (Fig. 3E). These preliminary results are in agreement with the above described differences in the metabolism of proximal versus distal tubule segments. In addition, the use of intravital MPM for imaging mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was tested in preliminary studies using iv injected MitoSox-Red in mice one month after STZ+L-NAME-induced diabetes and hypertension, as described previously.8, 74, 75 High intensity of MitoSox-Red fluorescence was observed in the distal tubule-cortical collecting duct system and in proximal tubules (Fig. 3F), consistent with significant ROS generation by renal cells in this condition. In addition to confirming metabolic differences between proximal and distal tubule segments, these studies provided preliminary feasibility data for imaging cell metabolism in podocytes in vivo. Other intravital MPM imaging studies evaluated glucose metabolism,76 and used fluorescence lifetime imaging, which showed benefit compared to conventional MPM imaging and revealed renal cell-type specific metabolic signatures.77 These MPM imaging studies of many intracellular organelles were instrumental in uncovering several new proximal tubule mechanisms and their roles in a variety of kidney diseases.

Figure 3. Intravital MPM imaging of cell metabolism in the living mouse kidney.

A–D: Serial MPM imaging of the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in the same glomerulus and surrounding tubule segments before (A, control) and after iv injected MitoTracker-Red (red)(B, Pre-IRI), and 10 min after ischemia-reperfusion injury (C, Post-IRI). Plasma was labeled with FITC-conjugated albumin (green). G: glomerulus, PT: proximal tubule. D: Statistical summary of the changes in MitoTracker-Red fluorescence intensity in the PT in response to IRI. *p<0.05, n=10 each. E: The highest intensity of MitoTracker-Red fluorescence was observed in cells around glomerular capillaries (podocytes, arrows), and in the distal tubule (DT). F: Intravital MPM imaging of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation using iv injected MitoSox-Red (red) in STZ+L-NAME-treated diabetic and hypertensive mice. High intensity of MitoSox-Red fluorescence was observed in the distal tubule and cortical collecting duct (CCD) in addition to proximal tubules (PT). Scale bars are 20 μm.

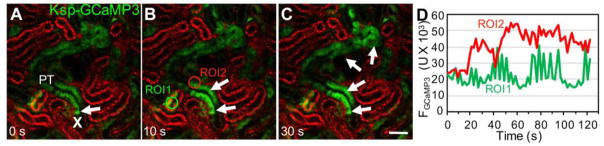

New intravital MPM imaging approaches have been established to investigate cytosolic parameters of proximal tubule cells, including pH and calcium.8, 34, 78, 79 MPM imaging of proximal tubule segments in the rat kidney loaded with the pH-sensitive dye BCECF visualized the development of a high pH microdomain near the bottomof the brush border in response to an acute rise of blood pressure,78 which may be a new important mechanism in pressure natriuresis (inhibition of proximal tubule sodium reabsorption). Regarding cytosolic calcium changes and calcium signaling in renal cell types, MPM imaging studies used the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP3 (a fusion protein containing the calmodulin-binding domain from the myosin light chain kinase also called M13 peptide, the circularly permutated green fluorescent protein, and the calmodulin) expressed in podocytes, and established the role of purinergic calcium signaling via purinergic receptor type Y2 receptors in primary and secondary (propagating) podocyte injury, cell clustering, and migration.34 Cell calcium imaging in tubular epithelial cells in vivo has been established using transgenic rats80 or mice expressing GCaMP proteins.21 Basal levels, and ligand and drug-induced alterations in cell calcium levels in proximal and distal tubule-collecting duct epithelial cells were measured successfully,21, 80 which opens new possibilities for future physiologic and pharmacologic investigations. Figure 4A–D demonstrates the use of a Cre-lox-based mouse model for intravital calcium imaging of both proximal and distal tubule epithelial cells, using previously described techniques34, 79 and kidney-specific cadherin Ksp/GCaMP3 mice.21 Focal, temporary, and reversible laser injury was used as before17, 34 that induced a cell-to-cell propagating calcium wave downstream along the proximal tubule segment (Fig. 4A–D, and Supplementary movie 3). Besides the elevated cell calcium at downstream sites in response to the injury, time-lapse GCaMP3 fluorescence intensity recordings at baseline or unaffected sites revealed typical, two-component oscillations in proximal tubule cell calcium (Fig. 4D). These oscillations are due to two classic physiological regulatory mechanisms of GFR and renal blood flow autoregulation, the myogenic tone of the afferent arteriole, and the kidney-specific tubuloglomerular feedback that maintain regular nephron GFR oscillations with a faster (0.12 Hz, cycle time about 10 s) and a slower (0.023 Hz, cycle time about 45 s) frequency.11, 17, 19 Detailed characterization of these hemodynamics-induced mechanosensitive calcium responses and their role in cell functions will help improve our understanding of the homeostatic balance of proximal and distal tubule cells. From the technical point of view, these GCaMP-based transgenic approaches have several advantages over earlier in vivo MPM calcium imaging methods in kidney tubules that used classic fluorophores.79

Figure 4. Intravital MPM imaging of injury-induced proximal tubule cell calcium signaling in Ksp-GCaMP3 mice.

A–C: Select proximal tubule segments (PT, green) are labeled by the Ksp-driven Cre/lox-mediated expression of the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP3. Note the fragmented rather than continuous epithelial cell labeling. The site of laser-induced single PT cell injury is indicated by “X”, and the resulting elevations in cell [Ca2+] that propagated to downstream tubule segments within 30 s are shown by arrows on panels B–C. Plasma was labeled red using Albumin-Alexa594, which also appears endocytosed in select early PT segments. Bar is 50 μm. D: Representative recordings of GCaMP3 fluorescence intensity at an unaffected upstream site (ROI1, green) and downstream from the injury site (ROI2, red).

Fluorescence imaging may be combined with superresolution nanoscopy modalitites or electron microscopy to study cell ultrastructure, for example structure-function relationships of podocyte foot process effacement and the molecular architecture of the glomerular filtration barrier.55, 81 The use of state-of-the-art high resolution imaging techniques may be applied to kidney biopsies for integrative analysis of genome-wide transcriptional variation, spatial distribution of cell states, molecular signatures, and subcellular architecture in both healthy kidney and various disease states.

Multiplexed fluorescence and label-free imaging of human renal pathology

Histological assessment of renal cell types, their functional and metabolic state, as well as changes in the interstitial architecture (kidney fibrosis) is essentially important in both clinical pathology and basic research using animal models of CKD. However, standard histology techniques and their blind evaluation in renal pathology are cumbersome. Recently, advanced optical microscopy techniques have been developed for hassle-free and label-free, unbiased, and highly sensitive characterization of kidney fibrosis using second-harmonic generation (SHG) and fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM).82 These approaches take advantage of highly efficient MPM excitation of intrinsic (auto) fluorescence and its detection by FLIM (mainly originating from reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, flavins within cells, and/or mitochondria) and fibrillar collagen (high accumulation in the extracellular matrix in renal fibrosis) capable of generating strong SHG signals.83 Ratiometric SHG/FLIM imaging provided highly sensitive and quantitative measurements of renal fibrosis compared to the gold-standard Masson's trichrome and Picrosirius Red histology methods, because collagen SHG increases, but autofluorescence FLIM decreases during fibrosis progression.82 The technique also eliminates the need for operator intervention (bias) and allows for automation. This approach was also greatly benefited by making modifications to microscope hardware, and the development and applications of deep tissue imaging using the new DIVER (Deep Imaging Via Enhanced-Photon Recovery) microscope, featuring high-sensitivity detection of forward-propagating SHG and a recently developed phasor approach to autofluorescence FLIM.84 Potential future combination with recently developed and highly popular tissue clearing techniques (such as CLARITY), quantitative imaging of renal cell states and tissue fibrosis in the entire kidney biopsy or large tissue volumes would become possible in 3D.85

Here we provide examples for the multiplex imaging analysis of the pathological changes in cell functions and tissue architecture in fixed human kidney sections (Fig. 5). Similarly to the SHG/FLIM ratiometric approach discussed above,82 these preliminary studies used quantitative imaging of the level of tissue fibrosis by the ratio of collagen SHG and tissue autofluorescence (by MPM imaging) in fixed nephrectomy samples (using approved IRB protocols HS-15-00298 and HS-16-00378 at the University of Southern California). For detecting SHG, a multiphoton laser at 946 nm, and a CFP emission filter at 473±10 nm was used, while tissue autofluorescence was detected by a GFP filter at 514±10 nm. Moderate levels of homogenous SHG signals were found around the peritubular interstitium in female, while intense, focally accumulated SHG signals were present in male patients’ kidneys (Fig. 5A–C). In addition, representative examples of four-channel multiplex analysis of cell and tissue variables in human renal pathologies are shown in Fig. 5D–E. Measuring tissue fibrosis and tissue autofluorescence signals, cell proliferation, and cell density simultaneously can establish the imaging-based signature of cell functional and metabolic states and interstitial structures in human kidney sections and biopsy tissue. Multiplex imaging methods can be further developed to use the above illustrated signals as surrogates to track and quantify renal pathology development, objectively define disease subgroups and molecular pathways and targets for novel therapies.

Figure 5. Multiplex imaging analysis of the pathological changes in cell functions and tissue architecture in fixed human kidney sections.

A–C: Quantitative imaging of the level of tissue fibrosis by the ratio of second harmonic generation (SHG, cyan) and tissue autofluorescence (green) in fixed nephrectomy samples of 50–60 years old age-matched female (A) and male (B) patients. Note the moderate, homogenous SHG signal around the peritubular interstitium in female (A) versus the intense, focally accumulated SHG signal in male (B, arrow) kidney. C: Example of potential quantitative imaging analysis of kidney fibrosis showing lower levels in female kidney tissues. D–E: Representative examples of four-channel multiplex analysis of cell and tissue variables in human renal pathologies. Measuring tissue fibrosis by SHG (cyan) and tissue autofluorescence (green) signals, cell proliferation (Ki67 immunofluorescence, arrows, red in D) or podocyte density (p57 immunofluorescence, arrows, red in E), and cell nuclei (DAPI, dark blue).

In summary, new renal cell and tissue imaging techniques significantly advanced the field of kidney research, and are ideally suited for numerous applications in future kidney precision medicine projects. Renal cell imaging has helped our mechanism-based understanding of renal pathologies. It can provide the most sensitive, accurate, fast, and automated quantitation of renal tissues, and has great potential for improving the precision of diagnostic and treatment paradigms for individual patients with AKI or CKD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health grants DK064324 and DK100944 to J.P-P.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kretzler M, Sedor JR. Introduction: Precision Medicine for Glomerular Disease: The Road Forward. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35:209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M. Renal biopsy-driven molecular target identification in glomerular disease. Pflugers Arch. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-2006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. [Accessed 7/17/2017];Kidney Precision Medicine Project. 2016 https://wwwniddknihgov/research-funding/research-programs/kidney-precision-medicine-project-kpmp.

- 5.Dunn KW, Sandoval RM, Kelly KJ, Dagher PC, Tanner GA, Atkinson SJ, Bacallao RL, Molitoris BA. Functional studies of the kidney of living animals using multicolor two-photon microscopy. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2002;283:C905–C916. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00159.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molitoris BA, Sandoval RM. Intravital multiphoton microscopy of dynamic renal processes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1084–1089. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00473.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peti-Peterdi J. Multiphoton imaging of renal tissues in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1079–1083. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00385.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peti-Peterdi J, Burford JL, Hackl MJ. The first decade of using multiphoton microscopy for high-power kidney imaging. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F227–233. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00561.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peti-Peterdi J, Morishima S, Bell PD, Okada Y. Two-photon excitation fluorescence imaging of the living juxtaglomerular apparatus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F197–201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00356.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall AM, Molitoris BA. Dynamic multiphoton microscopy: focusing light on acute kidney injury. Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29:334–342. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peti-Peterdi J, Kidokoro K, Riquier-Brison A. Novel in vivo techniques to visualize kidney anatomy and function. Kidney Int. 2015;88:44–51. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuh CD, Haenni D, Craigie E, Ziegler U, Weber B, Devuyst O, Hall AM. Long wavelength multiphoton excitation is advantageous for intravital kidney imaging. Kidney Int. 2016;89:712–719. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson E, Levene MJ, Torres R. Multiphoton microscopy with clearing for three dimensional histology of kidney biopsies. Biomed Opt Express. 2016;7:3089–3096. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.003089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahler S, Yu H, Suleiman H, Krishnan GM, Saunders BT, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Zinselmeyer BH, Shaw AS. Intravital and Kidney Slice Imaging of Podocyte Membrane Dynamics. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3285–3290. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endlich N, Simon O, Gopferich A, Wegner H, Moeller MJ, Rumpel E, Kotb AM, Endlich K. Two-photon microscopy reveals stationary podocytes in living zebrafish larvae. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:681–686. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackl MJ, Burford JL, Villanueva K, Lam L, Susztak K, Schermer B, Benzing T, Peti-Peterdi J. Tracking the fate of glomerular epithelial cells in vivo using serial multiphoton imaging in new mouse models with fluorescent lineage tags. Nat Med. 2013;19:1661–1666. doi: 10.1038/nm.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peti-Peterdi J, Sipos A. A high-powered view of the filtration barrier. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1835–1841. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall AM, Schuh CD, Haenni D. New frontiers in intravital microscopy of the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26:172–178. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang JJ, Toma I, Sipos A, McCulloch F, Peti-Peterdi J. Quantitative imaging of basic functions in renal (patho)physiology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F495–502. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00521.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano D, Nishiyama A. Multiphoton imaging of kidney pathophysiology. J Pharmacol Sci. 2016;132:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peti-Peterdi J, Kidokoro K, Riquier-Brison A. Intravital imaging in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25:168–173. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiessl IM, Hammer A, Riquier-Brison A, Peti-Peterdi J. Just Look! Intravital Microscopy as the Best Means to Study Kidney Cell Death Dynamics. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36:220–236. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small DM, Sanchez WY, Gobe GC. Intravital Multiphoton Imaging of the Kidney: Tubular Structure and Metabolism. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1397:155–172. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3353-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sipos A, Toma I, Kang JJ, Rosivall L, Peti-Peterdi J. Advances in renal (patho)physiology using multiphoton microscopy. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1188–1191. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Murari K, Li MJ, Li X. Integrated multimodal endomicroscopy platform for simultaneous en face optical coherence and two-photon fluorescence imaging. Opt Lett. 2012;37:362–364. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, van Es JH, van den Born M, Kroon-Veenboer C, Barker N, Klein AM, van Rheenen J, Simons BD, Clevers H. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lasagni L, Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, Lombardi D, Nardi S, Peired A, Becherucci F, Mazzinghi B, Sisti A, Romoli S, Burger A, Schaefer B, Buccoliero A, Lazzeri E, Romagnani P. Podocyte Regeneration Driven by Renal Progenitors Determines Glomerular Disease Remission and Can Be Pharmacologically Enhanced. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:248–263. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khoury CC, Khayat MF, Yeo TK, Pyagay PE, Wang A, Asuncion AM, Sharma K, Yu W, Chen S. Visualizing the mouse podocyte with multiphoton microscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wanner N, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Goedel M, Stickel N, Zeiser R, Walz G, Moeller MJ, Grahammer F, Huber TB. Unraveling the role of podocyte turnover in glomerular aging and injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:707–716. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hohne M, Ising C, Hagmann H, Volker LA, Brahler S, Schermer B, Brinkkoetter PT, Benzing T. Light microscopic visualization of podocyte ultrastructure demonstrates oscillating glomerular contractions. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegerist F, Blumenthal A, Zhou W, Endlich K, Endlich N. Acute podocyte injury is not a stimulus for podocytes to migrate along the glomerular basement membrane in zebrafish larvae. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43655. doi: 10.1038/srep43655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appel D, Kershaw DB, Smeets B, Yuan G, Fuss A, Frye B, Elger M, Kriz W, Floege J, Moeller MJ. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burford JL, Villanueva K, Lam L, Riquier-Brison A, Hackl MJ, Pippin J, Shankland SJ, Peti-Peterdi J. Intravital imaging of podocyte calcium in glomerular injury and disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2050–2058. doi: 10.1172/JCI71702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulte K, Berger K, Boor P, Jirak P, Gelman IH, Arkill KP, Neal CR, Kriz W, Floege J, Smeets B, Moeller MJ. Origin of parietal podocytes in atubular glomeruli mapped by lineage tracing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:129–141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013040376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ronconi E, Sagrinati C, Angelotti ML, Lazzeri E, Mazzinghi B, Ballerini L, Parente E, Becherucci F, Gacci M, Carini M, Maggi E, Serio M, Vannelli GB, Lasagni L, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hickmann L, Steglich A, Gerlach M, Al-Mekhlafi M, Sradnick J, Lachmann P, Sequeira-Lopez MLS, Gomez RA, Hohenstein B, Hugo C, Todorov VT. Persistent and inducible neogenesis repopulates progenitor renin lineage cells in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaverina NV, Kadoya H, Eng DG, Rusiniak ME, Sequeira-Lopez ML, Gomez RA, Pippin JW, Gross KW, Peti-Peterdi J, Shankland SJ. Tracking the stochastic fate of cells of the renin lineage after podocyte depletion using multicolor reporters and intravital imaging. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, Carroll TJ, Self M, Oliver G, McMahon AP. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar S, Liu J, Pang P, Krautzberger AM, Reginensi A, Akiyama H, Schedl A, Humphreys BD, McMahon AP. Sox9 Activation Highlights a Cellular Pathway of Renal Repair in the Acutely Injured Mammalian Kidney. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1325–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang HM, Huang S, Reidy K, Han SH, Chinga F, Susztak K. Sox9-Positive Progenitor Cells Play a Key Role in Renal Tubule Epithelial Regeneration in Mice. Cell Rep. 2016;14:861–871. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barker N, Rookmaaker MB, Kujala P, Ng A, Leushacke M, Snippert H, van de Wetering M, Tan S, Van Es JH, Huch M, Poulsom R, Verhaar MC, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Lgr5(+ve) stem/progenitor cells contribute to nephron formation during kidney development. Cell Rep. 2012;2:540–552. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Dahr SS, Li Y, Liu J, Gutierrez E, Hering-Smith KS, Signoretti S, Pignon JC, Sinha S, Saifudeen Z. p63+ ureteric bud tip cells are progenitors of intercalated cells. JCI Insight. 2017:2. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trepiccione F, Soukaseum C, Iervolino A, Petrillo F, Zacchia M, Schutz G, Eladari D, Capasso G, Hadchouel J. A fate-mapping approach reveals the composite origin of the connecting tubule and alerts on “single-cell”-specific KO model of the distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F901–f906. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00286.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi A, Mugford JW, Krautzberger AM, Naiman N, Liao J, McMahon AP. Identification of a multipotent self-renewing stromal progenitor population during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:650–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, Henderson JM, Ebert BL, Humphreys BD. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lemos DR, Marsh G, Huang A, Campanholle G, Aburatani T, Dang L, Gomez I, Fisher K, Ligresti G, Peti-Peterdi J, Duffield JS. Maintenance of vascular integrity by pericytes is essential for normal kidney function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F1230–f1242. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00030.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Duffield JS. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–1627. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sutton TA, Fisher CJ, Molitoris BA. Microvascular endothelial injury and dysfunction during ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1539–1549. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pippin JW, Kaverina NV, Eng DG, Krofft RD, Glenn ST, Duffield JS, Gross KW, Shankland SJ. Cells of renin lineage are adult pluripotent progenitors in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F341–358. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00438.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, Zhang S, Cheng T, Inagami T, Ward K, Terreros DA, Lalouel JM. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension. 1999;34:1265–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sequeira Lopez ML, Pentz ES, Nomasa T, Smithies O, Gomez RA. Renin cells are precursors for multiple cell types that switch to the renin phenotype when homeostasis is threatened. Dev Cell. 2004;6:719–728. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pippin JW, Sparks MA, Glenn ST, Buitrago S, Coffman TM, Duffield JS, Gross KW, Shankland SJ. Cells of renin lineage are progenitors of podocytes and parietal epithelial cells in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:542–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grgic I, Brooks CR, Hofmeister AF, Bijol V, Bonventre JV, Humphreys BD. Imaging of podocyte foot processes by fluorescence microscopy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:785–791. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011100988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burford JL, Gyarmati G, Shirato I, Kriz W, Lemley KV, Peti-Peterdi J. Combined use of electron microscopy and intravital imaging captures morphological and functional features of podocyte detachment. Pflugers Arch. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-2020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi D, Park E, Jung E, Seong YJ, Yoo J, Lee E, Hong M, Lee S, Ishida H, Burford J, Peti-Peterdi J, Adams RH, Srikanth S, Gwack Y, Chen CS, Vogel HJ, Koh CJ, Wong AK, Hong YK. Laminar flow downregulates Notch activity to promote lymphatic sprouting. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1225–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI87442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi I, Chung HK, Ramu S, Lee HN, Kim KE, Lee S, Yoo J, Choi D, Lee YS, Aguilar B, Hong YK. Visualization of lymphatic vessels by Prox1-promoter directed GFP reporter in a bacterial artificial chromosome-based transgenic mouse. Blood. 2011;117:362–365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-298562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Devi S, Li A, Westhorpe CL, Lo CY, Abeynaike LD, Snelgrove SL, Hall P, Ooi JD, Sobey CG, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ. Multiphoton imaging reveals a new leukocyte recruitment paradigm in the glomerulus. Nat Med. 2013;19:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nm.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finsterbusch M, Hall P, Li A, Devi S, Westhorpe CL, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ. Patrolling monocytes promote intravascular neutrophil activation and glomerular injury in the acutely inflamed glomerulus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E5172–5181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606253113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Colombaro V, Jadot I, Decleves AE, Voisin V, Giordano L, Habsch I, Malaisse J, Flamion B, Caron N. Lack of hyaluronidases exacerbates renal post-ischemic injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2015;88:61–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Decleves AE, Caron N, Nonclercq D, Legrand A, Toubeau G, Kramp R, Flamion B. Dynamics of hyaluronan, CD44, and inflammatory cells in the rat kidney after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rouschop KM, Roelofs JJ, Claessen N, da Costa Martins P, Zwaginga JJ, Pals ST, Weening JJ, Florquin S. Protection against renal ischemia reperfusion injury by CD44 disruption. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2034–2043. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wuthrich RP. The proinflammatory role of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions in renal injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2554–2556. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.11.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salmon AH, Ferguson JK, Burford JL, Gevorgyan H, Nakano D, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Peti-Peterdi J. Loss of the endothelial glycocalyx links albuminuria and vascular dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1339–1350. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Snelgrove SL, Lo C, Hall P, Lo CY, Alikhan MA, Coates PT, Holdsworth SR, Hickey MJ, Kitching AR. Activated Renal Dendritic Cells Cross Present Intrarenal Antigens After Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Transplantation. 2017;101:1013–1024. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huen SC, Cantley LG. Macrophages in Renal Injury and Repair. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:449–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee SA, Noel S, Sadasivam M, Hamad ARA, Rabb H. Role of Immune Cells in Acute Kidney Injury and Repair. Nephron. 2017 doi: 10.1159/000477181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mort RL, Ford MJ, Sakaue-Sawano A, Lindstrom NO, Casadio A, Douglas AT, Keighren MA, Hohenstein P, Miyawaki A, Jackson IJ. Fucci2a: a bicistronic cell cycle reporter that allows Cre mediated tissue specific expression in mice. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:2681–2696. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2015.945381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dickson LE, Wagner MC, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA. The proximal tubule and albuminuria: really! J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:443–453. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wagner MC, Campos-Bilderback SB, Chowdhury M, Flores B, Lai X, Myslinski J, Pandit S, Sandoval RM, Wean SE, Wei Y, Satlin LM, Wiggins RC, Witzmann FA, Molitoris BA. Proximal Tubules Have the Capacity to Regulate Uptake of Albumin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:482–494. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Endres BT, Sandoval RM, Rhodes GJ, Campos-Bilderback SB, Kamocka MM, McDermott-Roe C, Staruschenko A, Molitoris BA, Geurts AM, Palygin O. Intravital Imaging of the Kidney in a Rat Model of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00466.2016. ajprenal.00466.02016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hall AM, Rhodes GJ, Sandoval RM, Corridon PR, Molitoris BA. In vivo multiphoton imaging of mitochondrial structure and function during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;83:72–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Janjoulia T, Fletcher NK, Giani JF, Nguyen MT, Riquier-Brison AD, Seth DM, Fuchs S, Eladari D, Picard N, Bachmann S, Delpire E, Peti-Peterdi J, Navar LG, Bernstein KE, McDonough AA. The absence of intrarenal ACE protects against hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2011–2023. doi: 10.1172/JCI65460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toma I, Kang JJ, Sipos A, Vargas S, Bansal E, Hanner F, Meer E, Peti-Peterdi J. Succinate receptor GPR91 provides a direct link between high glucose levels and renin release in murine and rabbit kidney. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2526–2534. doi: 10.1172/JCI33293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hato T, Friedman AN, Mang H, Plotkin Z, Dube S, Hutchins GD, Territo PR, McCarthy BP, Riley AA, Pichumani K, Malloy CR, Harris RA, Dagher PC, Sutton TA. Novel application of complementary imaging techniques to examine in vivo glucose metabolism in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F717–f725. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00535.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hato T, Winfree S, Day R, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA, Yoder MC, Wiggins RC, Zheng Y, Dunn KW, Dagher PC. Two-Photon Intravital Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of the Kidney Reveals Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Signatures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016101153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brasen JC, Burford JL, McDonough AA, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Peti-Peterdi J. Local pH domains regulate NHE3-mediated Na(+) reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;307:F1249–1262. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00174.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Svenningsen P, Burford JL, Peti-Peterdi J. ATP releasing connexin 30 hemichannels mediate flow-induced calcium signaling in the collecting duct. Front Physiol. 2013;4:292. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szebenyi K, Furedi A, Kolacsek O, Csohany R, Prokai A, Kis-Petik K, Szabo A, Bosze Z, Bender B, Tovari J, Enyedi A, Orban TI, Apati A, Sarkadi B. Visualization of Calcium Dynamics in Kidney Proximal Tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2731–2740. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suleiman H, Zhang L, Roth R, Heuser JE, Miner JH, Shaw AS, Dani A. Nanoscale protein architecture of the kidney glomerular basement membrane. Elife. 2013;2:e01149. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ranjit S, Dobrinskikh E, Montford J, Dvornikov A, Lehman A, Orlicky DJ, Nemenoff R, Gratton E, Levi M, Furgeson S. Label-free fluorescence lifetime and second harmonic generation imaging microscopy improves quantification of experimental renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2016;90:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Christie R, Nikitin AY, Hyman BT, Webb WW. Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7075–7080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ranjit S, Dvornikov A, Stakic M, Hong SH, Levi M, Evans RM, Gratton E. Imaging Fibrosis and Separating Collagens using Second Harmonic Generation and Phasor Approach to Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13378. doi: 10.1038/srep13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torres R, Velazquez H, Chang JJ, Levene MJ, Moeckel G, Desir GV, Safirstein R. Three-Dimensional Morphology by Multiphoton Microscopy with Clearing in a Model of Cisplatin-Induced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1102–1112. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.