Abstract

The complement and neutrophil defense systems, as major components of innate immunity, are activated during inflammation and infection. For neutrophil migration to the inflamed region, we hypothesized that the complement activation product C5a induces significant changes in cellular morphology before chemotaxis. Exposure of human neutrophils to C5a, dose- and time-dependently resulted in a rapid C5a receptor-1 (C5aR1)-dependent shape-change, indicated by enhanced flow cytometric forward-scatter area values. Similar changes were observed after incubation with zymosan-activated serum and in blood neutrophils during murine sepsis, but not in mice lacking the C5aR1. In human neutrophils, Amnis high-resolution digital imaging revealed a C5a-induced decrease in circularity and increase in the cellular length/width ratio. Biomechanically, microfluid optical stretching experiments indicated significantly increased neutrophil deformability early after C5a stimulation. The C5a-induced shape changes were inhibited by pharmacological blockade of either the Cl−/HCO3−-exchanger or the Cl−-channel. Furthermore, actin polymerization assays revealed that C5a exposure resulted in a significant polarization of the neutrophils. The functional polarization process triggered by ATP–P2X/Y-purinoceptor interaction was also involved in the C5a-induced shape changes, because pre-treatment with suramin blocked not only the shape changes but also the subsequent C5a-dependent chemotactic activity.

In conclusion, the data suggest that the anaphylatoxin C5a regulates basic neutrophil cell processes by increasing the membrane elasticity and cell size as a consequence of actin-cytoskeleton polymerization and reorganization, transforming the neutrophil into a migratory cell able to invade the inflammatory site and subsequently clear pathogens and molecular debris.

Introduction

The complement system plays a key role in the recognition, marking, and clearance of pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs, respectively) during inflammation and infection [1–3]. Upon complement activation, the generated anaphylatoxin C5a exerts manifold pro-inflammatory effects, including neutrophil recruitment, activation and an increase in intracellular pH in concert with extracellular acidification [4,5]. Evidence suggests that to accomplish migration and tissue penetration for bacterial defense, neutrophils may undergo some volume and extreme morphological changes, for example, from a spherical to a flattened shape, which is accompanied by rapid “expansion” of the plasma membrane surface [6]. More than two decades earlier, it was reported that exposure of neutrophils to chemoattractants, including N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP), interleukin 8 and C5a, induced calcium-independent actin polymerization and ruffling and polarization of the cells [7]. Mechanistically, the polymerization of actin filaments and the reorganization of the cytoskeletal network are major contributors to adjusting the mechanical properties of neutrophils during interstitial migration [8]. In this regard, C5a in its active and desarginated forms was shown to alter cellular morphology and surface adhesion in several cell types, including neutrophils [9]. Moreover, an autocrine purinergic signaling system, especially via the ATP-activated P2X7 receptor, is involved in shape polarization of these cells [10,11].

To ensure the functionality of such cellular processes, a balanced intracellular volume regulation appears to be of fundamental importance. In this regard, studies have shown that pathophysiologic conditions, including hypoxia and ischemia [12,13], and inflammatory processes [14] are associated with changes in neutrophil cellular volume. Furthermore, an actively regulated and directed influx of fluid via different ion channels and transporter systems is regarded as a prerequisite for neutrophil chemotactic capacity, because cell migration is abolished in a hyperosmolar environment [15–18]. In this context, activation of the electro-neutral sodium-potassium chloride cotransporter (NKCC) induces a synchronous influx of Na+, K+ and Cl− into the cell, leading to an osmotically triggered water influx. Additionally, the coupled activation of the ubiquitous sodium-proton exchanger 1 (NHE1) and the chloride-bicarbonate exchanger results in the net uptake of sodium chloride and fluid. Although the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (NBC) is mainly known for its role in HCO3− reabsorption in the kidney, there is experimental evidence indicating that NBC activity is also involved in volume regulation [19] and was found to be expressed by neutrophils [20]. To date, several chemoattractants, hormones and growth factors have been shown to alter the activity of these transport systems. However, the respective activation mechanisms and the subsequent cellular effects are not fully understood.

Here we provide evidence that interaction between the complement activation product C5a and its cellular receptor C5aR1 leads to increased deformability and a marked alteration of the neutrophil cell shape that is dependent on cellular influx of osmotically active chloride ions, actin polymerization and autocrine P2X/Y signaling. In a translational animal model, we found similar alterations in neutrophil morphology during experimental sepsis.

Material and Methods

Reagents

Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany).

Isolation of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils

Informed written consent was obtained from all individuals, the study has been performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the procedures have been approved by the Independent Local Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany (no. 94/14). Whole blood from healthy volunteers was drawn into syringes containing 3.2% trisodium citrate (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) as anticoagulant. Neutrophils were isolated by Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences, Solingen, Germany) followed by dextran sedimentation. After hypotonic lysis of residual erythrocytes, neutrophils were resuspended as indicated in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), Hank’s balanced salt solution with Ca2+/Mg2+ (HBSS) or RPMI 1640 (all Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). For Amnis high-resolution digital imaging, neutrophils were isolated as described by Barnes et al. [21].

Preparation of zymosan-activated serum

To prepare zymosan-activated serum, 0.04 g zymosan was diluted in 1 ml distilled water. The solution was centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature (RT) and the pellet was washed with DPBS. After a further centrifugation step, the supernatant was removed and the zymosan pellet was resuspended in 20 ml DPBS. A total of 1 ml of the zymosan-DPBS stock solution was centrifuged (350 × g, 5 min, RT) and the supernatant was removed. For serum activation, the zymosan pellet was resuspended in 200 μl serum to a final concentration of 10 mg zymosan/ml serum and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to activate the complement cascade.

Neutrophil stimulation

Isolated neutrophils (2 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with human recombinant C5a (0.1–20 nM), C3a (1000 ng/ml) (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), zymosan-activated serum (5, 10, 20 μl) or non-stimulated serum for up to 30 min at 37°C.

For inhibition of the C5aR1, neutrophils were pretreated with the selective small peptide C5aR1 antagonist (C5aR1A) AcF[OPdChaWR] [22,23] (10 μg/ml) for 10 min at 37°C before C5a stimulation. For the blockade of central volume-associated ion-transporter systems, neutrophils were pretreated with the respective inhibitor for 20 min at 37°C before C5a incubation. Herein, (4-cyano-benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)guanidine methanesulfonate (NHE1 inhibitor, 5–100 μM) was used as a Na+/H+-exchanger inhibitor, amiloride (200 μM) as a Na+-channel inhibitor, bumetanide (100 μM) as an NKCC inhibitor, omeprazole (10 μM) as a K+/H+-ATPase inhibitor, ouabain (100 μM) as a Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor, UK5099 (400 μM) as a Cl−/HCO3−-exchanger inhibitor, S0859 (30 μM) as a Na+/HCO3−-cotransporter inhibitor and 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB, 100 μM) as a Cl−-channel inhibitor. Furthermore, suramin (200 μM) was used to block P2X/Y-purinoceptors. For inhibition experiments, cells were incubated in HBSS medium ± inhibitors. Experiments using the Na+/HCO3− sodium bicarbonate co-transporter inhibitor S0859 were performed in RPMI medium, containing 24 mM sodium bicarbonate.

Chemotaxis assay

Isolated neutrophils (5 × 106 cells/ml in DPBS) were labelled with 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and -6)-carboxyfluorescein, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Following a washing step with DPBS, cells were pre-incubated with suramin (200 μM) for 15 min at 37°C. The neutrophils were loaded into the upper chambers of a 96-well chemotaxis mini-chamber (Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD). The lower chamber was loaded with C5a (10 nM) and separated from the upper chamber by a polycarbonate membrane of 3-μm porosity (Neuroprobe). The cells were incubated in the mini-chamber for 30 min at 37°C. To determine the neutrophil chemotactic activity, the number of cells that had migrated through the polycarbonate filters to the lower surface was determined by cytofluorometry (Cytofluor II; PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA). Samples were measured at least in quadruplicates.

Cell sizing by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II)

For cell size analysis, human and murine neutrophils were analyzed for forward-scattered (FSC) light with a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) using a 488-nm laser. The extent of scattering is dependent not only on particle size, but also on cell shape and surface topography [24,25]. Herein, the integrals (“areas”) of the FSC pulses (FSC-A) generated by neutrophils were determined. To calculate neutrophil cell size, the FSC-A values generated by polystyrene beads of different diameters were used to prepare a standard curve (see Figure 1A and B), allowing a direct association between FSC-A values and cell diameters. A minimum of 10,000 neutrophils were analyzed per sample.

Figure 1. Neutrophil shape changes following C5a stimulus.

(A) Representative dot plots (upper images) and histograms (lower images) of neutrophil light-scatter properties after control (Ctrl, left panel) or C5a (right panel) stimulation in comparison to beads of defined sizes in flow cytometric measurements using a BD FACSCanto II. Neutrophils are shown in red; beads are depicted in green (10 μm, P2), blue (15 μm, P3) and purple (20 μm, P4). (B) Correlation between FSC-A signal and bead diameter in flow cytometric assessment (BD FACSCanto II); n=22. (C) Time-dependent effect of C5a on cell size as assessed by FSC-A; n=3–4; *, p<0.05 compared to control. (D) Dose-dependent neutrophil size increase as assessed by FSC-A; n=4; *, p<0.05 compared to 0 nM.

High-resolution digital imaging

The Amnis ImageStream system (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to obtain morphological information of cells by capturing high-resolution multispectral images. After stimulation of isolated neutrophils with C5a (20 nM) or control (DPBS) for 5–10 min at 37°C, neutrophils were identified in the scatter plot, and data from 10,000 cells per sample were collected. Changes in cell shape were detected by pre-defined features using the IDEAS image analysis software (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). This included determination of the mean neutrophil circularity, which is the mean distance of the cell boundary from its center divided by the variation of this distance. The shape ratio, the minimal thickness of the cell divided by the length of the cell, was also determined.

Confocal microscopy

For confocal microscopy analysis, isolated neutrophils (6 × 106 cells/ml) were stimulated using C5a (20 nM) for up to 17 min at 37°C. A 50-μl cell suspension per condition was allowed to settle on the glass bottom of the microwell dishes and was then examined (without a cover slip) using a Zeiss 7000 scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Microfluidic optical stretching

C5a was dissolved in water and added to the neutrophils 1 h before experiments. Mechanical properties of the neutrophils were determined by optical stretching as described previously [26–29]. Optical stretching allows the assessment of cellular deformability without mechanical contact, which may otherwise lead to cellular stimulation. Deformation (stretching) of cells suspended in a microfluidic channel is induced by forces generated by the momentum transfer from two counter-propagating laser beams to the cellular surface (see Figure 5B inset).

Figure 5. Morphological changes induced by C5a as assessed by confocal microscopy and optical stretching.

(A) Neutrophils were stimulated using C5a (20 nM) for up to 10 min at 37°C. Cells were allowed to settle on the glass bottom of microwell dishes and were then examined using a Zeiss 7000 scanning confocal microscope. (B) Deformation of neutrophils by optical stretching. Insert: neutrophils (green) suspended in a microfluidic channel (light blue) were deformed by forces (red) produced by the momentum transfer from counter-propagating laser beams (light red) to the cellular surface. The scatter plot depicts the relative peak deformation of individual neutrophils as determined by the changes of the cells’ diameter (insert, yellow arrow). Neutrophils were exposed to optical forces for 2 s. Peak deformability of neutrophils was significantly increased by 10 nM C5a. The horizontal lines represent the mean relative peak deformation ± SEM; ****, p<0.0001.

Actin cytoskeleton polymerization assay

Isolated human neutrophils were incubated for 10 min at 37°C in medium (RPMI with 5% fetal calf serum) with C5a after pre-incubation for 15 min with either C5aR1A or the Cl−-channel blocker and intracellular ATP blocker NPPB. For control, cells were left untreated or treated with C5aRA or NPPB alone. After incubation, cells were fixed and then F-actin was stained using phalloidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (green). Images of the cells were recorded using an iMic digital microscope (Till Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany).

Cecal ligation and puncture-induced murine sepsis

All animal studies were approved by the University of Ulm Committee on the Use and Care of Animals (approval number 988). Mice had unrestricted access to water and food. For experimental murine sepsis, male C57BL/6 mice (weighing 25–30 g, purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, USA) were used. Sepsis was induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as previously described [30]. Mice were anesthetized using a 2.5% sevoflurane (Sevorane; Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) and 97.5% oxygen mixture under a continuous flow via an inhalation mask. For analgesia, mice received buprenorphine 0.03 mg/kg body weight subcutaneously every 6–8 h after surgery. Following abdominal midline incision, 50 % of the cecum was ligated below the ileocecal valve, punctured using a 21-gauge needle and a small portion of feces was extruded to induce high-grade sepsis. The abdominal incision was closed in layers. Whole blood was collected 24 h after surgery into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-containing syringes and FSC-A values of a minimum of 10,000 neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry.

In vitro stimulation of neutrophils from knockout mice

For the in vitro stimulation experiments, blood was drawn from homozygous C5aR1 (C5aR1−/−) or C5aR2 (C5aR2−/−) gene knockout mice with a C57BL/6 background and from strain-matched wildtype (WT) animals (5–6 months old, weighing 25–35 g). The knockout mice were generated by Dr. Craig Gerard (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA). After hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, leukocytes were stimulated using murine recombinant C5a (10 nM) for up to 10 min at 37°C and the FSC-A values of a minimum of 10,000 neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test for multiple comparisons was performed to determine significant differences between experimental means when comparing several groups. For comparisons between two groups, statistical significance was calculated using Mann-Whitney U-test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

C5a-induced increase in neutrophil size as determined by FSC-A measurements

Flow cytometric analysis of isolated human neutrophils revealed an increase of the FSC-A values as early as 1 min and was significantly different 5 min after C5a stimulation in comparison to control incubation and as referenced to polystyrene beads of different predefined sizes (10, 15, 20 μm in diameter) (Figure 1A). The linear correlation between FSC-A values and particle diameters within the range 10–20 μm (Figure 1B) provides an estimation of the neutrophil size by flow cytometry. Based on this relationship, we found that incubation of neutrophils with C5a led to an early increase in neutrophil length, reaching a maximum after 10 min (Figure 1C), whereas C3a failed to alter neutrophil size (data not shown). Furthermore, increasing concentrations of C5a for 10 min led to a concentration-dependent increase in neutrophil length (Figure 1D).

The C5a-induced increase in the FSC-A values could be completely abolished by pretreatment of neutrophils using the C5aR1 antagonist C5aR1A (Figure 2A). In a more complex system, exposure of neutrophils to zymosan-activated autologous serum (with generated C5a) also resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in cell length, whereas non-stimulated serum did not alter the cell dimensions. Noteworthy, this zymosan-induced size effect could also be completely abolished by C5aR1 antagonism (Figure 2B). Moreover, neutrophils from WT mice and C5aR2 knockout (C5aR2−/−) mice exhibited a significant increase in cell length 5 min after stimulation with murine C5a. In striking contrast, under similar conditions, neutrophils from C5aR1 knockout mice (C5aR1−/−) failed to increase in cell size (Figure 2C). Interestingly, unstimulated C5aR2−/− animals displayed visibly increased FSC-A values compared to WT and C5aR1−/− mice. These flow cytometric results indicate that the C5a-induced FSC-A effects, reflecting to some extent the cell dimensions, were found with both human and mouse neutrophils and were dependent on C5aR1 signaling.

Figure 2. The increase in cell length is dependent on the C5aR1 and is manifest in a mouse model of sepsis.

(A) Preincubation with a C5aR1 antagonist (C5aR1A) inhibits the C5a-induced neutrophil shape change; n=6; *, p<0.001 compared to control; #, p<0.001 compared to C5a alone. (B) Cellular diameter as assessed by FSC-A after incubation with zymosan-activated or control serum and preincubation with C5aR1A; n=3–4; *, p<0.05 compared to control serum; #, p<0.01 compared to 20 μl/ml zymosan-activated serum w/o antagonist. (C) Whole blood was drawn from wildtype (WT) mice and from homozygous C5aR1 or C5aR2 knockout (−/−) animals. After hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, leukocytes were stimulated with murine recombinant C5a (10 nM) and FSC-A values were recorded; n=3; *, p<0.05 compared to 0 min. (D) Sepsis was induced in C57BL/6 mice by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). After 24 h, FSC-A values of neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry; n=6 (Ctrl), n=10 (CLP); *, p<0.001 compared to control animals.

Sepsis-induced changes in neutrophil size

Because increased C5a plasma levels have been found during experimental and human sepsis, we determined neutrophil cell size in murine CLP-induced sepsis. The flow cytometry based analysis of neutrophils from mice with sepsis showed a significant increase in the FSC-A values 24 h after CLP induction when compared to neutrophils of control mice (Figure 2D).

Potential mechanisms of the C5a-induced shape change

To investigate possible mechanisms of the C5a-induced effects in neutrophils, we blocked central ion channels/transporters that may be associated with intracellular volume regulation (Table). Inhibition of the NHE1 by amiloride or a specific NHE1 inhibitor ((4-cyano-benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)guanidine, methanesulfonate) failed to reduce the C5a-mediated increase in cell size, neither alone nor in combination with the H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor omeprazole. Likewise, blockade of the Na+/HCO3−-cotransporter by S0859 or the Na+/K+/2Cl−-cotransporter by bumetanide revealed no significant inhibitory effects. Additionally, the K+-channel blocker tetraethylammonium chloride, which can also inhibit aquaporins to some extent [31], did not alter the C5a-induced size increase (Table). In contrast, the Cl−/HCO3−-exchanger inhibitor UK5099, which blocks the exchange of intracellular bicarbonate with extracellular chloride, partially reduced the C5a effect on neutrophils (Figure 3A). To determine whether the C5a-induced increase in neutrophil length was mediated by the influx of chloride ions, we examined the action of the Cl−-channel blocker NPPB. Pre-incubation of neutrophils with NPPB also significantly reduced the C5a-induced increase in their length (Figure 3B), indicating that C5a stimulation resulted in an influx of osmotically active chloride ions into neutrophils.

Figure 3. Neutrophil shape change is dependent on chloride influx.

Before C5a stimulation, neutrophils were incubated with (A) an inhibitor of the Cl−/HCO3−-exchanger (UK5099, 400 μM) or (B) a global inhibitor of chloride channels (NPPB, 100 μM) for 20 min. FSC-A values were determined by flow cytometry; n=6–10; *, p<0.05 compared to control; #, p<0.05 compared to C5a alone.

Specific morphological changes of neutrophils by anaphylatoxin C5a

To investigate the C5a-mediated neutrophil shape alteration in more morphological detail, we used the Amnis ImageStream system, which combines the features of a flow cytometer and a fluorescence microscope. Surprisingly, the analysis of the mean cell area by IDEAS software revealed only marginal increases in the overall cell size after C5a treatment in terms of cellular swelling (data not shown). However, we also determined the mean circularity of the neutrophils by analysis of the mean distance of the cell boundary from its center divided by the variation of this distance. The more the shape deviates from a circle, the greater the variation and therefore the lower the circularity value. We found that incubation of neutrophils with C5a (in this set of experiments with 200 ng/ml which revealed maximal effects in a pilot dose-response study, data not shown) resulted in a significant reduction of cell circularity after 5 min based on a cut-off value of 10 when compared to control samples (Figure 4A and B). Furthermore, we analyzed the shape ratio of the neutrophils, which was defined by the minimal cell thickness divided by the cell length. When neutrophils were stimulated with C5a, the number of cells that displayed a shape ratio of less than 0.66 was increased (to 54%) in comparison to neutrophils after control incubation (39%). Moreover, the combined analysis of the shape ratio (<0.66) together with low circularity values (<10) of neutrophils revealed that the percentage of these cells was significantly increased after 5 min of C5a stimulation (Figure 4C, D and E).

Figure 4. Addition of C5a induces neutrophil shape changes, as analyzed by high-resolution spectral imaging in a flow-cytometry environment.

Neutrophils were maintained at 37°C for 5 or 10 min (controls) or reacted with 20 nM C5a for the same time periods. The samples were kept on ice for 20 min and brought to room temperature just before analysis. Changes in both the circularity (A,B) and shape ratio (C) induced by C5a are evident. Low circularity values (<10) represent a high deviation from circular shape. Dot plots that evaluate both the shape ratio and circularity (D,E) display the same trends. All points were run in duplicate. There was a significant difference between the samples examined after 5 min for C5a treatment vs. the untreated samples for low circularity and for the shape ratio and low circularity combined (p=0.04 and p=0.03, respectively). When taking the mean of the results for both time points, the differences between C5a-treated and untreated samples was significant for both criteria (p=0.004 and p=0.002, respectively). Representative of two separate experiments.

For further morphological evaluation, neutrophils were analyzed by confocal microscopy. After control incubation, the cells appeared uniformly spherical, whereas upon C5a exposure, they lost their circularity, adopting a rather polarized cell shape (Figure 5A).

Biomechanical changes of neutrophils upon exposure to C5a

Whether such a polarized cell shape was also associated with altered cellular mechanics was the objective of the next set of experiments. Optical stretching was applied to compare the deformability of neutrophils exposed to 10 nM C5a with that of untreated cells (Figure 5B). Pooled data for neutrophils from five healthy individuals demonstrated that the majority of neutrophils exhibited significantly increased deformability in response to C5a (Figure 5B).

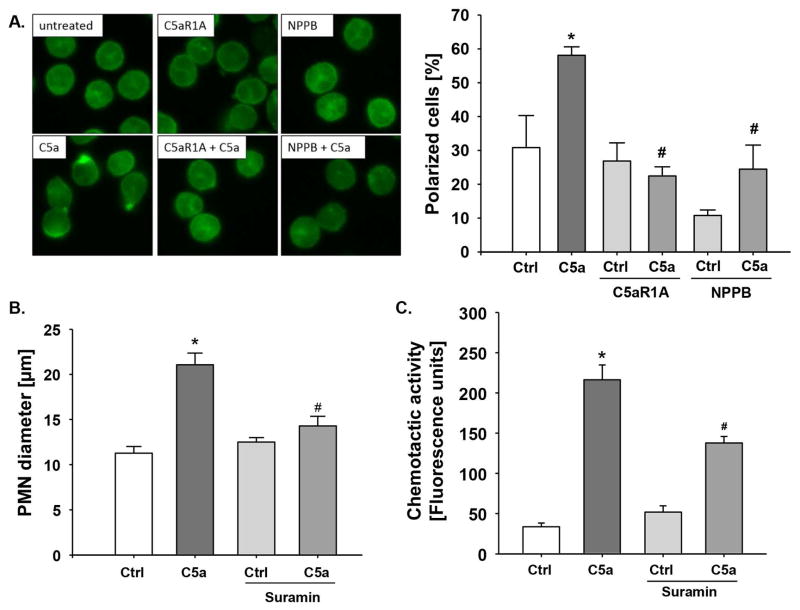

C5a-induced change in cell morphology involves actin-cytoskeleton reorganization and is dependent on ATP signaling

A major driver for cellular mechanics and shape changes is the actin-cytoskeleton. Early after C5a exposure, human blood neutrophils stained with phalloidin-FITC (green) displayed clear evidence of F-actin polymerization and polarization (Figure 6A). The signs of C5a-induced actin reorganization were abolished in the presence of either C5aRA or NPPB (Figure 6A) but not in the presence of UK5099 (data not shown).

Figure 6. Involvement of P2Y activation in C5a-induced functional polarization of neutrophils.

(A) Isolated neutrophils were exposed to the indicated conditions and F-actin was stained with phalloidin-FITC (green). C5a stimulation induced actin polymerization and polarization of the neutrophil actin cytoskeleton. The percentage of polarized cells was significantly reduced after incubation with C5aR1A or NPPB; n=3; *, p<0.05 vs. Ctrl; #, p<0.05 vs. C5a alone. Functional polarization blockade by pre-incubation of neutrophils with suramin (200 μM, 20 min) resulted in a decrease of (B) C5a-enhanced FSC-A values and (C) C5a-induced chemotactic activity; *, p<0.001 compared to control; #, p<0.001 compared to C5a alone.

To determine whether the C5a-mediated changes of the neutrophil features were associated with functional cell polarization, we used suramin to block the P2X/Y-purinoceptors that induce a polarization process after ATP stimulus [32]. To screen for cell shape changes, we again determined the FSC-A values by flow cytometry. The C5a-induced increase of the FSC-A could be significantly reduced by inhibition of the purinoceptors (Figure 6B), suggesting that the C5a-induced changes in the neutrophil shape were dependent on P2X/Y signaling. Because changes in cell shape are regarded as a prerequisite for migrational function, the effect of P2X/Y inhibition on C5a-stimulated chemotaxis was investigated. After pre-incubation of neutrophils with suramin, the chemotactic activity towards C5a was significantly reduced (Figure 6C), indicating that the C5a-mediated activation of the P2X/Y signaling and the associated changes in cell shape were required for neutrophil chemotaxis.

Discussion

Manifold effects of the complement activation product C5a on key functions of neutrophils have been identified [33]. Because the functional activity of neutrophils is dependent on intracellular-volume regulation, we investigated the effect of C5a on neutrophil cell volume and cell shape and the regulatory signaling mechanisms (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Potential mechanisms regulating cellular shape change and chemotactic activity after complement stimulus.

C5a generated during systemic inflammatory processes activates neutrophils via the C5aR1 and simultaneously induces autocrine ATP stimulation resulting in reorganization of the cytoskeleton, and an influx of sodium chloride causing a slight increase in the cell size, together facilitating morphological changes necessary for chemotaxis towards inflammatory stimuli.

Neutrophil stimulation using C5a resulted in a concentration- and time-dependent increase of FSC-A values during flow cytometric analysis as an indication of increased cell length or size (Figure 1). In this context, O’Flaherty et al. have shown that neutrophil stimulation using chemotactic agents leads to their aggregation [34]. However, in the present study, a C5a-induced aggregation of neutrophils could be excluded by a discriminative analysis of FSC-A and FSC-height signals (data not shown). The observed effect could be effectively blocked by a C5aR1 antagonist. Furthermore, there was no shape change in neutrophils from C5aR1 knockout mice after C5a stimulation in contrast to neutrophils from C5aR2 knockout and WT animals (Figure 2). These data suggest that the C5a stimulus induces a C5aR1-dependent intracellular signaling cascade with subsequent osmotic swelling and cellular shape change. In previous studies, similar shape changes by various chemoattractants, including C5a in excessive amounts, have been described [35] and linked to functional alterations such as induction of the oxidative burst [36].

On a technical level, it should be indicated that determination of cell size by flow cytometric means is by far more complex than so far appreciated [37]. Although various optical scatter and fluorescence parameters (FSC-A, FSC width, side-scatter area, and 450/50 area) may estimate the cellular volume (and were all increased after C5a exposure in the present study, data not shown), an investigation of electronic cell-volume distributions by Coulter counting showed only a trend of an enhanced neutrophil diameter after C5a exposure (resulting in an approximately 5% total increase, data not shown). This indicates that enhanced FSC-A values alone failed to precisely determine cell volume, but may reflect an increased cell length with marginal if any volume alterations.

However, several previous studies addressing cell-volume regulation revealed that neutrophil stimulation with chemoattractants resulted in cell swelling, and that neutrophil size was increased after migration into inflamed tissue [17,38,39]. Remarkably, in tumor cells, stimulation with zymosan-activated serum – known to generate substantial amounts of C5a – resulted in a 20 % increase in cell diameter, which was associated with an enhanced chemotactic migration behavior [40]. Similarly, in neutrophils, an fMLP- or osmosis-induced increase in cellular volume was accompanied by enhanced chemotactic activity [15,17], which was associated with some reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton [41]. Here, we demonstrated that C5a induces rapid actin polymerization and polarization of the cells (Figure 6A). Of note, in the actin-cytoskeleton reorganization experiments, C5a was applied by micro-injection from a distinct direction; however, uniform alignment of the cells in direction of the gradient was not apparent in the present staining. This might indicate a general activation and priming of the cells upon sensing a C5a gradient or the gradient was no longer present after the incubation period. As a limitation of the study, no combined exposure to PAMPs and C5a was performed, which may result in a clearer response to the molecular danger signal. In regard to actin disassembly, cofilin-dependent (de)polymerization is known to be a pH-sensitive process [42]. However, inhibition of the NHE1, the H+/K+-ATPase or the sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter did not reduce the C5a effect in the present investigation (Table), whereas fMLP-induced volume changes could be blocked by combined inhibition of the NHE1 and H+/K+-ATPase in earlier studies [16]. Furthermore, activation of aquaporins as a driving mechanism shown in neutrophils after stimulation with fMLP [31] could be excluded.

It is somehow surprising that amiloride was incapable of inhibiting C5a-induced cellular shape change although it was most potent to inhibit an increase in intracellular pH in our recent report [5]. However, in the context of the C5a-induced shape change/cellular volume, we could not find this effect using amiloride. In a previous study, Shimizu Y et al. studied the Cl− efflux from neutrophils, which was triggered by factors elevating intracellular calcium such as C5a. This C5a effect was not inhibited by amiloride [43], supporting our data. Furthermore, replacing extracellular Na+, but not the presence of amiloride, was shown to inhibit fMLP-caused neutrophil polarization [44].

In contrast, the blockade of the Cl−/HCO3−-exchanger significantly reduced the C5a-induced shape change, indicating an underlying Cl−-mediated mechanism as suggested by Giambelluca et al. [45]. This is supported by the inhibitory effects of global chloride-channel blockade (Figure 3) and might be even more pronounced by combined inhibition of chloride channels and exchangers. Of note, the inhibitory effect of NPPB on the C5a response might not be restricted to its blocking function on chloride channels. NPPB also acts as an effective protonophore, potentially disturbing cytosolic pH and subsequent intracellular ion and fluid load [46]. Furthermore, NPPB treatment leads to depletion of intracellular ATP [46], which, together with the P2X/Y-blocking results in the present study, suggests an involvement of ATP signaling in the C5a-induced alteration of the neutrophil cell shape as discussed below.

Alteration in Cl−-homeostasis by various inflammatory mediators seems to play an important functional role in neutrophils. Chloride is considered crucial for the host defense of neutrophils by generating potent chlorine bleach, contributing to anti-microbial micromilieu in phagosomes and thereby killing bacteria. Exposure of neutrophils to fMLP, IL-8 or C5a resulted in an enhanced Cl− efflux which was proposed not to be causal for the shape change [43]. Another report described that fMLP activates the anion transporters ClC-3 and IClswell [48]. Niflumic acid (NFA) and phloretin as non-selective inhibitors of ClC-3 and IClswell function, both reduced chemotactic activity and velocity, whereas NFA in a mM range and tamoxifen in a uM range (as specific IClswell inhibitor) were capable to inhibit celluar shape change in response to a fMLP-gradient [48]. Future studies should address the effect of C5a on these anion transporters.

Further analysis of neutrophils by Amnis ImageStream found only marginal increases in the mean cell area (data not shown). Instead, a C5a-induced change in the cell shape could be detected consisting of a reduction of cell circularity and an increase of the cell length in comparison to the cell width (Figure 4). Therefore, the increase of FSC-A values after C5a stimulation might rather represent a change in the cellular shape and presumably formation of pseudopodia over the entire cellular surface than an increase in the overall cell volume. This shape change was associated with a C5a-induced increase in neutrophil deformability as assessed by optical stretching [29] (Figure 5). Altered neutrophil mechanics with substantial cellular deformation determined by this technique have been described as a requirement for migration processes through very small pores [29], suggesting that C5a influences neutrophil motility in confined spaces. Formation of pseudopodia was apparently induced by local alkalinization via the NHE1 and influx of fluid following directed/targeted activation of fMLP receptors on neutrophils [41,49]. However, in the present study, the NHE1 appears to play only a minor role, if at all, in the C5a-associated cellular shape changes.

In the case of the chemoattractant fMLP, a local release of ATP has been observed, which lead to reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and polarization of neutrophils [11,32,50]. This pathway can also be activated by membrane deformation due to mechanical or osmotic stress [51,52]. To investigate whether the C5a-induced polarization in our study was dependent on ATP interactions, we blocked the P2Y receptor using suramin, which significantly reduced the C5a-mediated increase of the FSC-A values (Figure 6). Furthermore, the C5a-induced chemotaxis was significantly reduced by blocking the P2Y signaling, which may be due to the inhibition of the P2Y-mediated polarization process in neutrophils. In contrast to the in vitro chemotaxis situation where neutrophils are exposed to a C5a gradient, the global excessive generation of C5a during systemic inflammation in vivo [33,53] may be responsible for the shape changes and might not necessarily require a specific chemoattractant gradient.

As a limitation of the study, we cannot exclude other mechanisms to be also involved in cell shape regulation by C5a as we did not perform broad-range dose-response experiments for most inhibitors that were used, and might have missed other specific ion transporter/exchange systems relevant for the cellular volume and ion balance.

In our animal experiments, neutrophils from C5aR1−/−, but not from C5aR2−/− mice, were resistant to the C5a-induced cell shape changes. In a translational approach, it is tempting to speculate that specific blockade of the C5aR1 might inhibit excessive and ubiquitous neutrophil migration into host tissue. Of note, there was a visible alteration in basal cell shape in C5aR2−/− mice (Figure 2), which might indicate that absence of C5aR2 as a postulated modulator of the pro-inflammatory response [54,55] leads to a permanently enhanced pro-inflammatory signaling via C5aR1 with subsequent shape change. Future studies need to clarify to what extent C5aR1 blockade during the inflammatory response will modulate cellular shape change and subsequent functions.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the complement activation product C5a is involved in basic cell regulatory processes (Figure 7) by modulation of chloride channels and transporters and changing the cell shape (increased length and decreased width) as well as membrane formability. This occurs via actin-cytoskeleton reorganization and polarization, all of which transform the neutrophil into a migratory cell able to invade inflammatory sites and target and clear pathogens and debris.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SD, RW, EMC, MAL, KP, TM, and DM performed the research; RPT, SP, HB, FG and MSHL designed the research study; JDL contributed the C5aR1A; SD, RW, EMC, TE, MW, EB, MK, and TM analyzed the data; SD, RPT, RW, SP, HB and MSHL wrote the paper. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG) assigned to M. Huber-Lang (KFO200, HU823/3-2, and CRC1149, project A01) and H. Barth (CRC1149, project A04) and by grants to J. Lambris from the National Institute of Health (AI068730) and from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement number 602699 (DIREKT). We thank M. Frick (Institute of General Physiology, University of Ulm) for providing access to the iMic digital microscope.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Denk S, Perl M, Huber-Lang M. Damage- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns and alarmins: keys to sepsis? Eur Surg Res. 2012;48:171–179. doi: 10.1159/000338194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganter MT, Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Shaffer LA, Walsh MC, Stahl GL, et al. Role of the alternative pathway in the early complement activation following major trauma. Shock. 2007;28:29–34. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180342439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasque P. Complement: a unique innate immune sensor for danger signals. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward PA. The dark side of C5a in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:133–142. doi: 10.1038/nri1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denk S, Neher MD, Messerer DAC, Wiegner R, Nilsson B, Rittirsch D, et al. Complement C5a Functions as a Master Switch for the pH Balance in Neutrophils Exerting Fundamental Immunometabolic Effects. J Immunol. 2017;198:4846–4854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewitt S, Francis RJ, Hallett MB. Ca(2)(+) and calpain control membrane expansion during the rapid cell spreading of neutrophils. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4627–4635. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lepidi H, Zaffran Y, Ansaldi JL, Mege JL, Capo C. Morphological polarization of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes in response to three different chemoattractants: an effector response independent of calcium rise and tyrosine kinases. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 4):1771–1778. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renkawitz J, Sixt M. Mechanisms of force generation and force transmission during interstitial leukocyte migration. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:744–750. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis ES, Chen H, Sfyroera G, Monk PN, Kohl J, Ricklin D, et al. C5a receptor-dependent cell activation by physiological concentrations of desarginated C5a: insights from a novel label-free cellular assay. J Immunol. 2012;189:4797–4805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:201–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman PJ, Grana WA. The changes in human synovial fluid osmolality associated with traumatic or mechanical abnormalities of the knee. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:179–181. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(88)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compan V, Baroja-Mazo A, Lopez-Castejon G, Gomez AI, Martinez CM, Angosto D, et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2012;37:487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simchowitz L, Cragoe EJ., Jr Inhibition of chemotactic factor-activated Na+/H+ exchange in human neutrophils by analogues of amiloride: structure-activity relationships in the amiloride series. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;30:112–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritter M, Schratzberger P, Rossmann H, Woll E, Seiler K, Seidler U, et al. Effect of inhibitors of Na+/H+-exchange and gastric H+/K+ ATPase on cell volume, intracellular pH and migration of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:627–638. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosengren S, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Migration-associated volume changes in neutrophils facilitate the migratory process in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1623–C1632. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Bao Y, Zhang J, Woehrle T, Sumi Y, Ledderose S, et al. Inhibition of Neutrophils by Hypertonic Saline Involves Pannexin-1, CD39, CD73, and Other Ectonucleotidases. Shock. 2015;44:221–227. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwab A, Rossmann H, Klein M, Dieterich P, Gassner B, Neff C, et al. Functional role of Na+- J Physiol. 2005;568:445–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giambelluca MS, Ciancio MC, Orlowski A, Gende OA, Pouliot M, Aiello EA. Characterization of the Na/HCO3(−) cotransport in human neutrophils. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:982–990. doi: 10.1159/000358669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes CR, Mandell GL, Carper HT, Luong S, Sullivan GW. Adenosine modulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced neutrophil activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:1851–1857. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finch AM, Wong AK, Paczkowski NJ, Wadi SK, Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, et al. Low-molecular-weight peptidic and cyclic antagonists of the receptor for the complement factor C5a. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1965–1974. doi: 10.1021/jm9806594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber-Lang MS, Riedeman NC, Sarma JV, Younkin EM, McGuire SR, Laudes IJ, et al. Protection of innate immunity by C5aR antagonist in septic mice. FASEB J. 2002;16:1567–1574. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0209com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson GC, Tennant RC, Carpenter DC, Sarau HM, Kon OM, Barnes PJ, et al. A novel flow cytometric assay of human whole blood neutrophil and monocyte CD11b levels: upregulation by chemokines is related to receptor expression, comparison with neutrophil shape change, and effects of a chemokine receptor (CXCR2) antagonist. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole AT, Garlick NM, Galvin AM, Hawkey CJ, Robins RA. A flow cytometric method to measure shape change of human neutrophils. Clin Sci (Lond) 1995;89:549–554. doi: 10.1042/cs0890549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekpenyong AE, Whyte G, Chalut K, Pagliara S, Lautenschlager F, Fiddler C, et al. Viscoelastic properties of differentiating blood cells are fate- and function-dependent. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guck J, Ananthakrishnan R, Mahmood H, Moon TJ, Cunningham CC, Kas J. The optical stretcher: a novel laser tool to micromanipulate cells. Biophys J. 2001;81:767–784. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lautenschlager F, Paschke S, Schinkinger S, Bruel A, Beil M, Guck J. The regulatory role of cell mechanics for migration of differentiating myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15696–15701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811261106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paschke S, Weidner AF, Paust T, Marti O, Beil M, Ben-Chetrit E. Technical advance: Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by colchicine is modulated through viscoelastic properties of subcellular compartments. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1091–1096. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:31–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loitto VM, Forslund T, Sundqvist T, Magnusson KE, Gustafsson M. Neutrophil leukocyte motility requires directed water influx. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:212–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junger WG. Purinergic regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2528–2540. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber-Lang MS, Younkin EM, Sarma JV, McGuire SR, Lu KT, Guo RF, et al. Complement-induced impairment of innate immunity during sepsis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3223–3231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Flaherty JT, Kreutzer DL, Showell HJ, Ward PA. Influence of inhibitors of cellular function on chemotactic factor-induced neutrophil aggregation. J Immunol. 1977;119:1751–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith CW, Hollers JC, Patrick RA, Hassett C. Motility and adhesiveness in human neutrophils. Effects of chemotactic factors. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:221–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI109293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrengruber MU, Geiser T, Deranleau DA. Activation of human neutrophils by C3a and C5A. Comparison of the effects on shape changes, chemotaxis, secretion, and respiratory burst. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzur A, Moore JK, Jorgensen P, Shapiro HM, Kirschner MW. Optimizing optical flow cytometry for cell volume-based sorting and analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grinstein S, Furuya W. Amiloride-sensitive Na+/H+ exchange in human neutrophils: mechanism of activation by chemotactic factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:755–762. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worthen GS, Henson PM, Rosengren S, Downey GP, Hyde DM. Neutrophils increase volume during migration in vivo and in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:1–7. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lam WC, Delikatny EJ, Orr FW, Wass J, Varani J, Ward PA. The chemotactic response of tumor cells. A model for cancer metastasis. Am J Pathol. 1981;104:69–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yonezawa N, Nishida E, Sakai H. pH control of actin polymerization by cofilin. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14410–14412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu Y, Daniels RH, Elmore MA, Finnen MJ, Hill ME, Lackie JM. Agonist-stimulated Cl− efflux from human neutrophils. A common phenomenon during neutrophil activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:1743–1751. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90429-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haston WS, Shields JM. Signal transduction in human neutrophil leucocytes: effects of external Na+ and Ca2+ on cell polarity. J Cell Sci. 1986;82:249–261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.82.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giambelluca MS, Gende OA. Cl(−)/HCO(3)(−) exchange activity in fMLP-stimulated human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:567–571. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lukacs GL, Nanda A, Rotstein OD, Grinstein S. The chloride channel blocker 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropyl-amino) benzoic acid (NPPB) uncouples mitochondria and increases the proton permeability of the plasma membrane in phagocytic cells. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80992-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang G, Nauseef WM. Salt, chloride, bleach, and innate host defense. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:163–172. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4RU0315-109R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volk AP, Heise CK, Hougen JL, Artman CM, Volk KA, Wessels D, et al. ClC-3 and IClswell are required for normal neutrophil chemotaxis and shape change. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34315–34326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803141200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi H, Aharonovitz O, Alexander RT, Touret N, Furuya W, Orlowski J, et al. Na+/H+ exchange and pH regulation in the control of neutrophil chemokinesis and chemotaxis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C526–C534. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00219.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verghese MW, Kneisler TB, Boucheron JA. P2U agonists induce chemotaxis and actin polymerization in human neutrophils and differentiated HL60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15597–15601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodin P, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: ATP release. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:959–969. doi: 10.1023/a:1012388618693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yegutkin G, Bodin P, Burnstock G. Effect of shear stress on the release of soluble ecto-enzymes ATPase and 5′-nucleotidase along with endogenous ATP from vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:921–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unnewehr H, Rittirsch D, Sarma JV, Zetoune F, Flierl MA, Perl M, et al. Changes and regulation of the C5a receptor on neutrophils during septic shock in humans. J Immunol. 2013;190:4215–4225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bamberg CE, Mackay CR, Lee H, Zahra D, Jackson J, Lim YS, et al. The C5a receptor (C5aR) C5L2 is a modulator of C5aR-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7633–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li R, Coulthard LG, Wu MC, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. C5L2: a controversial receptor of complement anaphylatoxin, C5a. FASEB J. 2013;27:855–864. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.