Abstract

Objective

Aspirin exhibits anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory properties - two potentially risk factors for depression. The relationship between aspirin use and depression, however, remains unclear. We investigated whether the aspirin use is associated with a decreased incidence of depressive symptoms in a large North American cohort.

Methods

Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) dataset, a multi-center, longitudinal study on community-dwelling adults was analyzed. Aspirin use was defined through self-report in the past 30 days and confirmed by a trained interviewer. Incident depressive symptoms were defined as a score of ≥ 16 in the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale.

Results

A total of 137 participants (mean age 65 years, 55.5% female) were using aspirin at baseline. Compared to 4,003 participants not taking aspirin, no differences in CES-D at baseline were evident (p=0.65). After a median follow-up time of 8 years, the incidence of depressive symptoms was similar in those taking aspirin at baseline (43; 95%CI=3–60) and in aspirin non-users (38; 95%CI=36–41) per 1,000 years; log-rank test=0.63). Based on Cox’s regression analysis adjusted for eleven potential confounders, aspirin use was not significantly associated with the development of depressive symptoms (Hazard Ratio=1.12; 95%CI=0.78–1.62; p=0.54). Adjustment for propensity scores or the use of propensity score matching did not alter the results.

Conclusion

Our study found that after adjustment for confounders, prescription of aspirin offered no significant protection against incident depressive symptoms. Whether aspirin is beneficial in a sub-group of depression with high levels of inflammation remains to be investigated in future studies.

Keywords: aspirin, depression, epidemiology, cohort, survey, psychiatry

INTRODUCTION

It is known that aspirin exerts effects on the inflammatory cascades, irreversibly inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX)–1, and modifying enzyme activity of COX-2, suppressing production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes.(Vane and Botting, 2003) These anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet mechanisms are the biological underpinning for which aspirin is used in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular conditions.(Berger et al., 2011) Moreover these effects have led to the assumption that aspirin could have positive effects on other diseases, such as dementia (Nilsson et al., 2003), cancer (Rothwell et al., 2010) and mental disorders.(Berk et al., 2013; Solmi et al., 2015)

Atherosclerosis and inflammation are two well-known risk factors for a number of psychiatric conditions.(Berk et al., 2013) A growing body of evidence has suggested that people who are depressed have higher levels of serum inflammatory cytokines.(Miller and Raison, 2016; Strawbridge et al., 2015) A recent meta-analysis of 82 studies comprising 3,212 participants with MDD vs. 2,798 healthy controls found that people with MDD have higher peripheral levels of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.(Kohler, Cristiano; Freitas, Thiago; Maes et al., 2016) Similarly, depressed people are more likely to have cardiometabolic abnormalities and atherosclerotic lesions.(Pizzi et al., 2012; Tiemeier et al., 2004) Recent meta-analyses have suggested that medications with an anti-inflammatory effect such as statins(Salagre et al., 2016) and celecoxib(Köhler et al., 2014) may improve depressive symptoms. Aspirin may also improve atherosclerotic lesions and decrease inflammatory parameters, thus preventing the onset of depression.

The literature regarding the possible impact of aspirin on depression is limited and unclear. Two observational studies did not find any significant association between the use of aspirin and the development of depression.(Glaus et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2016) An open-label trial found that aspirin did not provide any benefit as a treatment for a current major depressive episode and was associated with several side effects when added to citalopram in ten subjects with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD).(Ghanizadeh and Hedayati, 2014) Conversely, another interventional study reported that aspirin is beneficial when added to selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) in patients with MDD who had failed to respond to an antidepressant trial.(Mendlewicz et al., 2006) Considering that aspirin is a relatively inexpensive drug, its potential utility for the prevention of incident depressive symptoms could be of public health relevance.

Given the aforementioned limitations in the literature, we aimed to investigate the effect of aspirin on the onset of depressive symptomatology in a large cohort of North American people participating in the Osteoarthritis Initiative.

METHODS

Data source and subjects

All participants in this study were recruited as part of the ongoing, publicly and privately funded, multicenter, and longitudinal Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) study (http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/). Specific datasets used were those recorded during baseline and screening evaluations (November 2008) (V00) and those evaluating the participants until the last evaluation available (96 months; V10). Eligibility criteria were: i) patients at high risk of knee osteoarthritis (OA); ii) patients with radiological evidence of knee OA; iii) both sexes. Excluded were: i) participants having a validated diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis or taking medications for this condition; ii) bilateral total knee joint replacement; iii) pregnancy; iv) unable to undergo a 3.0 Tesla MRI or unable to provide a blood sample; v) co-morbid conditions that could interfere with the study.

The participants were recruited from four clinical sites in the US (Baltimore, MD; Pittsburgh, PA; Pawtucket, RI; and Columbus, OH) between February 2004 and May 2006. All of the participants provided written informed consent. The OAI study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the OAI Coordinating Center, University of California at San Francisco.

Exposure

The use of aspirin was assessed using a specific questionnaire investigating the name of the prescription medicine, duration of use, formulation code (oral, rectal, topical etc.) in the 30 days before the interview. Trained interviewers checked the medications used by each participant in the last 30 days.

Outcome

The presence of depressive symptoms was derived from the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) instrument.(Radloff, 1977) The range of possible values for this scores is 0 to 60, where higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms.(Radloff, 1977) A cut-off of 16 was used for the diagnosis of depressive symptoms.(Lewinsohn et al., 1997; Veronese et al., 2016) The presence of depressive symptoms in the OAI was recorded at baseline and also during the following visits: V1 (12 months), V3 (24 months), V5 (36 months), V6 (48 months), V7 (60 months), V8 (72 months), V9 (84 months), and V10 (96 months).

Covariates

A number of variables was identified from the OAI dataset as potential confounders in the relationship between aspirin and incident depressive symptoms. These included: (1) physical activity evaluated through the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.(Washburn et al., 1999) This scale, validated in older populations, covers 12 different activities, such as walking, sports, and housework, and is scored from 0 to 400 and more; (2) race was defined as “white” vs. “other”; (3) smoking habits as “previous/current” vs. never; (4) educational level was categorized as “degree” vs. others; (5) yearly income as < vs. ≥ 50,000 $ or missing data; (6) co-morbidities assessed through the modified Charlson comorbidity score, with higher scores indicating an increased severity of conditions(Katz et al., 1996); (7) body mass index (BMI), as recorded by a trained nurse; and (8) the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) other than aspirin prescribed by a physician.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses included means and standard deviations (SDs) for quantitative measures, and percentages for all discrete variables by aspirin use status at baseline. The difference in baseline sample characteristics by aspirin use was tested by Student’s t-tests and Chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively.

We ran a multivariable Cox’s regression analysis with aspirin use at baseline as the exposure and incident depressive symptoms at follow-up visits as the outcome. Time to event was calculated as time to first detection of depressive symptoms. Factors used for adjustment (age, gender, BMI, race, PASE score, smoking habits, education, yearly income, Charlson comorbidity index, use of NSAIDS apart from aspirin, and CES-D at baseline) were those which reached a statistical significance between aspirin users and non-users at baseline or those significantly associated with depressive symptoms at follow-up (taking a p-value<0.05 as statistically significant). Furthermore, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was drawn to graphically display the non-adjusted cumulative incidence of depression by aspirin use at baseline. A log rank test was used to test the difference between aspirin users and non-users.

In order to assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted further analyses using the propensity score which was estimated by using a logistic regression model regressing baseline aspirin use on the above-mentioned 11 baseline covariates. We also conducted 4:1 nearest-neighbor propensity score matching. The covariate balance for the treated and matched control groups was tested by Student’s t-tests and Chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively. There were no significant differences in any of the baseline characteristics between the two groups (Supplementary Table 1). Multivariable Cox regression analysis adjusting for propensity score quintiles using the overall sample, and univariable Cox regression analysis using the matched controls were conducted to assess the association between aspirin use and incident depressive symptoms.

In order to assess the influence of multicolinearity, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) value for each independent variable. All VIFs were <2, indicating that multicolinearity was unlikely to be a problem in our analyses. All covariates were included in the models as categorical variables with the exception of age, BMI, PASE score, Charlson co-morbidity score, and CES-D points (continuous variables). Results of the Cox’s regression analysis were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas). All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was assumed for a p-value <0.05.

RESULTS

Study participants

Among 4,796 potentially eligible individuals, 264 were excluded due to missing baseline CES-D data, and 462 were excluded for having depression (i.e. CES-D ≥16) at baseline. Of the remaining, 4,070 participants, only 137 (3.6%) were using aspirin.

Descriptive analyses

The baseline characteristics by aspirin use are shown Table 1. People taking aspirin (n=137) were significantly older (p<0.0001), less physical active (p=0.002), richer (p=0.03), and more likely to be current or previous smokers (p=0.002) than those not taking aspirin (n=4,003). Conversely, no significant differences emerged in terms of percentage of women, BMI, race, education or use of other NSAIDs. As expected, people using aspirin reported a significantly higher Charlson co-morbidity score (likely due to a higher presence of CVD and diabetes), but no differences emerged in terms of baseline CES-D points [aspirin users 4.6 (SD 4.0) vs. non-users 4.8 (SD 4.1), p=0.65] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to aspirin treatment.

| Variable | Aspirin (n=137) | No aspirin (n=4003) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.3 (8.7) | 61.3 (9.2) | <0.0001 |

| Females (%) | 55.5 | 57.6 | 0.66 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 (4.4) | 28.4 (4.7) | 0.14 |

| White race (%) | 78.1 | 81.9 | 0.26 |

| PASE (points) | 141.7 (69.9) | 163.8 (82.1) | 0.002 |

| Smoking (previous/current) (%) | 56.6 | 45.9 | 0.002 |

| Degree (%) | 31.6 | 32.2 | 0.93 |

| Yearly income (<50,000 $) (%) | 55.3 | 65.1 | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Charlson co-morbidity score | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Heart attack (%) | 6.8 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 6.7 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Stroke (%) | 8.2 | 2.4 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17.6 | 6.8 | <0.0001 |

| Use of NSAIDs (%) | 19.7 | 23.9 | 0.31 |

|

| |||

| CES-D (points) | 4.6 (4.0) | 4.8 (4.1) | 0.65 |

Abbreviations: BMI Body Mass Index; PASE physical activity scale for the elderly; CES-D Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression.

Data are mean (SD) and percentage for continuous and categorical variables respectively.

P-values were calculated with Student’s t-tests and Chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively.

Association between baseline aspirin use and incident depressive symptoms

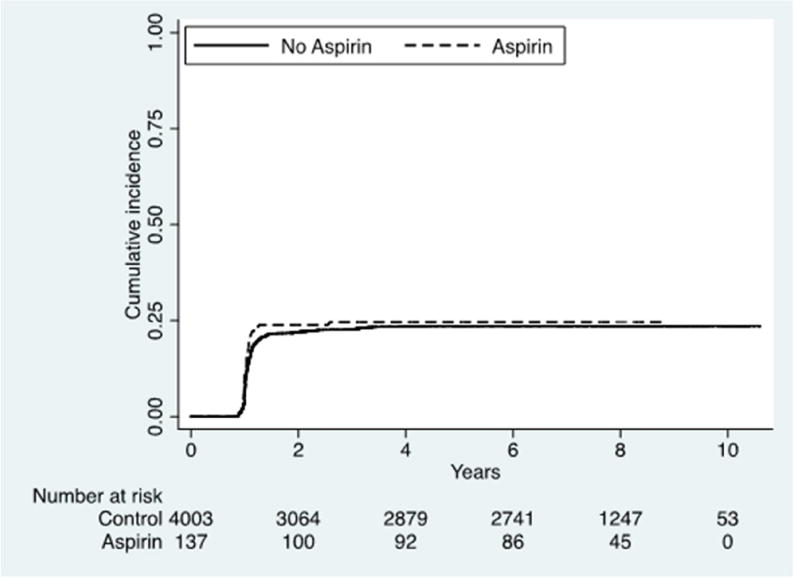

After a median period of 8 years, 967 individuals (23.4% of baseline population) developed depressive symptoms. The global incidence rate of depressive symptoms was 39 events for 1000 persons-year (95%CI=36–41). As shown in Figure 1, the incidence of depressive symptoms was similar in aspirin users at the baseline vs. non-users (incidence rate: 43; 95%CI=3–60 in aspirin users vs. 39; 95%CI=36–41 in non-users) (log-rank test p=0.63).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms by aspirin use at baseline.

Using a Cox’s regression analysis adjusted for eleven potential confounders, the use of aspirin was not associated with a significantly reduced risk of developing depressive symptoms (HR=1.12; 95% CI=0.78–1.62; p=0.54). Furthermore, the results of the Cox regression analysis adjusting for propensity score quintiles did not appreciably change the results (HR=1.08; 95%CI=0.75–1.56; p=0.67). This was also the case for the analysis using propensity-score matched controls (HR=0.95; 95%CI=0.63–1.42; p=0.79).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that use of aspirin is not associated with a decreased risk of incident depressive symptomatology over eight years of follow-up. These negative findings remained unaltered after adjustment for potential confounders or the use of a matched control.

At baseline, no significant differences emerged for several parameters investigated, including CES-D scores. As expected, the presence of co-morbidities was strongly associated with aspirin use which is likely to be due to a higher prevalence of CVD. One of the main indications for taking aspirin is the secondary prevention of CVD and primary prevention of CVD in high risk situations for CVD, particularly diabetes. Thus, the pre-existence of these conditions at baseline may have a role in explaining why aspirin was not effective in reducing the incidence of depressive symptoms during follow-up period. For example, many CVD patients would experience worsening of depression due to CVD itself.(Huffman et al., 2013) So apart from the CVD benefits from aspirin, this should be a further confounding factor that would only be partially controlled by baseline CES-D severity and the presence of any co-morbidity.

Our findings are in general agreement with those present in the literature, in which depressive symptoms do not appear to benefit from aspirin use. All studies(Ghanizadeh and Hedayati, 2014; Glaus et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2016), except one(Mendlewicz et al., 2006), reported that the use of aspirin was not associated with any favorable effect on depression. In comparison with these previous studies, the strength of our study includes the use of propensity score matching to further control for background sociodemographic variables. In addition, our study had the longest follow-up available thus far. Since both atherosclerosis and inflammation are possible risk factors for depression,(Taylor et al., 2013) the use of aspirin theoretically could decrease the incidence of depressive symptoms. A possible reason for our null findings could be that aspirin may increase rather than decrease the risk of hemorrhagic small cerebrovascular lesions, which could contribute to increasing the risk for vascular depression.(Almeida et al., 2010) In the Rotterdam Scan Study, for example, older adults who used aspirin were about three times as likely to show lobar microbleeds on magnetic resonance imaging compared to non-users.(Vernooij et al., 2009) Thus, it is possible that the beneficial effects of aspirin are counterbalanced by the higher incidence of micro-hemorrhagic events leading to an absence of effect. Furthermore, aspirin can increase the permeability of the gut barrier,(Hollander, 1999) which may drive the translocation of microbiota bacterial products, and thereby contribute to the pathophysiology of depression.(Slyepchenko et al., 2017)

Contrary to our findings, in a large meta-analysis(Köhler et al., 2014) involving 14 trials and 6,262 participants, the use of NSAIDs, other than aspirin, was associated with a decreased rate of depression and depressive symptoms. However, as stated by the authors, these data are affected by a high level of heterogeneity and a high risk of bias as well as a high rate of side effects.(Köhler et al., 2014) Among the drugs investigated, celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, seems the best in decreasing depressive symptoms. These data are in agreement with other works suggesting that only anti-inflammatories inhibiting COX-2 are able to improve depression.(Na et al., 2014) The mechanism is not known, but one animal study showed that COX-2 inhibition can decrease the age-dependent increase of hippocampal inflammatory markers, and it is thus likely that in humans this may prevent not only depression, but also other conditions strictly associated with depression, such as anxiety and cognitive decline.(Casolini et al., 2002) Since aspirin is more potent in its inhibition of COX-1 than COX-2(Rahola, 2012; Vane and Botting, 2003), it is possible that aspirin did not lead to any improvement in depressive symptoms for this reason. However, more research is needed, since other authors reported that the selective inhibition of COX-2 could also be dangerous for depression.(Maes, 2012)

Another explanation of the discrepancy between elevated inflammatory markers in MDD(Kohler, Cristiano; Freitas, Thiago; Maes et al., 2016) and the inefficacy of aspirin administration in preventing depressive symptoms could be found in the difference between depressive symptoms and MDD itself, or in the several subtypes of biological profiles within MDD. In particular, while depressive symptoms correlate with several adverse outcomes,(Maske et al., 2016) it has been observed that depressive symptoms are also present in the non-clinical general population.(Nakai et al., 2015) Moreover, while in MDD some studies do not confirm the inflammatory theory of depression,(Cassano et al., 2016) others strongly suggest a sub-population that could benefit from treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs.(Rapaport et al., 2015) Hence, our data cannot preclude the possibility that aspirin is beneficial in a sub-population of individuals with MDD.(Gallagher et al., 2016)

The present findings should be considered within the limitations of the study. First, our data considered people who received aspirin, but we were unable to consider the impact of the dose in our analyses. Similarly, we had no information on whether these subjects took aspirin for the prevention of any CVD or as a pain-killer. Second, the diagnosis of depressive symptoms was made only using the CES-D. Whilst the more formal assessment of the American Psychiatric Association’ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [DSM] criteria) was not used, the CES-D used many symptoms defined by (DSM-V) for a major depressive episode and is a broadly used instrument for assessing depressive symptoms in population studies, presenting sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 77%, respectively, when compared to clinical diagnosis.(Sharp and Lipsky, 2002) Third, we did not have any information regarding the presence of side effects during the follow-up period, despite the fact that it may be important in explaining our non-significant results. Fourth, due to the limited sample size, we were not able to assess whether the use of aspirin was associated with a decreased risk of depressive symptoms in some sub-groups, e.g. people with CVD. Fifth, we had no data about the actual continuous aspirin use from baseline, but we assumed that subjects were taking aspirin in the context of a long-term treatment. Finally, we did not have information regarding use of aspirin that was initiated after baseline. Since this was a study with a long median follow-up of 8 years, it is possible that the status of the participants changed during this time-frame. Whilst is it likely that those on aspirin remained on aspirin for chronic medical conditions, it is possible that some of the control participants started aspirin in some moment between baseline and follow-up. This is likely to have occurred, at least to some extent, since the participants in the OAI were chosen for having high risk of OA. In this case, a possible benefit of aspirin would be diluted in the analyses, and this could also underlie our null results.

In conclusion, the use of aspirin was not associated with decreased risk of depressive symptoms during eight years of follow-up in a large cohort of North American people. In spite of our results which suggest that aspirin may not protect from incident depressive symptoms, future controlled trials are warranted to investigate potential benefits of this drug in individuals with MDD and higher baseline peripheral inflammation.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Aspirin has anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic properties that could make this drug ideal for the treatment of depression.

In our study, we did not find any effect of aspirin on reducing the risk of depression in 4,000 participants over 8 years of follow-up.

Future randomized controlled trials are needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2- 2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262)funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

Role of founding source: The funding sources did not have any role in in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- Almeida OP, Alfonso H, Jamrozik K, Hankey GJ, Flicker L. Aspirin use, depression, and cognitive impairment in later life: The health in men study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JS, Lala A, Krantz MJ, Baker GS, Hiatt WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162 doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Dean OO, Drexhage HH, McNeil JJ, Moylan S, O’Neil A, Davey CG, Sanna L, Maes M, Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler M, Conway S, Ng L, Stanley E, Samokhvalov I, Merad M, Villagonzalo K, Dodd S, Dean OO, Gray K, Tonge B, Berk M, Leonard B, Maes M, Moylan S, Maes M, Wray N, Berk M, Berk M, Berk M, Conus P, Kapczinski F, Andreazza A, Yücel M, Wood S, Pantelis C, Malhi G, Dodd S, Bechdolf A, Amminger G, Hickie I, McGorry P, Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza A, Dean OO, Giorlando F, Maes M, Yücel M, Gama C, Dodd S, Dean B, Magalhães P, Amminger P, McGorry P, Malhi G, Maes M, Ruckoanich P, Chang Y, Mahanonda N, Berk M, Vane J, Botting R, Dai Y, Ge J, Rothwell P, Wilson M, Price J, Belch J, Meade T, Mehta Z, Rahola J, Breese C, Freedman R, Leonard S, Berk M, Wadee A, Kuschke R, O’Neill-Kerr A, Pasco J, Jacka F, Williams L, Henry M, Nicholson G, Kotowicz M, Berk M, Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim E, Lanctot K, Padmos R, Hillegers M, Knijff E, Vonk R, Bouvy A, Staal F, Ridder D, de Kupka R, Nolen W, Drexhage HH, Drexhage R, Heul-Nieuwenhuijsen L, van der Padmos R, Beveren N, van Cohen D, Versnel M, Nolen W, Drexhage HH, Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, Pollmacher T, Connor T, Leonard B, Kalivas P, O’Brien C, Basterzi A, Aydemir C, Kisa C, Aksaray S, Tuzer V, Yazici K, Goka E, Eller T, Vasar V, Shlik J, Maron E, Bilici M, Efe H, Koroglu M, Uydu H, Bekaroglu M, Deger O, Khanzode SS, Dakhale G, Khanzode SS, Saoji A, Palasodkar R, Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Eker S, Erdinc S, Vatansever E, Kirli S, Selley M, Forlenza M, Miller G, Peet M, Murphy B, Shay J, Horrobin D, Maes M, Vos N, De Pioli R, Demedts P, Wauters A, Neels H, Christophe A, Owen A, Batterham M, Probst Y, Grenyer B, Tapsell L, Hunsel F, Van Wauters A, Vandoolaeghe E, Neels H, Demedts P, Maes M, Herken H, Gurel A, Selek S, Armutcu F, Ozen M, Bulut M, Kap O, Yumru M, Savas H, Akyol O, Yanik M, Erel O, Kati M, Pal S, Dandiya P, Verleye M, Steinschneider R, Bernard F, Gillardin J, Lee C, Han E, Lee W, Eren I, Naziroglu M, Demirdas A, Celik O, Uguz A, Altunbasak A, Ozmen I, Uz E, Looney J, Childs H, Ng F, Berk M, Dean OO, Bush A, Fullerton J, Tiwari Y, Agahi G, Heath A, Berk M, Mitchell P, Schofield P, Dean OO, Buuse M, van den Bush A, Copolov D, Ng F, Dodd S, Berk M, Berk M, Johansson S, Wray N, Williams L, Olsson C, Haavik J, Bjerkeset O, Zuckerman L, Weiner I, Brown A, Muller N, Schwarz M, Korschenhausen D, Hampel H, Ackenheil M, Penning R, Muller N, Miller B, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B, Lin A, Kenis G, Bignotti S, Tura G, Jong R, De Bosmans E, Pioli R, Altamura C, Scharpe S, Maes M, Berckel B, van Bossong M, Boellaard R, Kloet R, Schuitemaker A, Caspers E, Luurtsema G, Windhorst A, Cahn W, Lammertsma A, Kahn R, Barnes D, Yaffe K, Rubio-Perez J, Morillas-Ruiz J, Tuppo E, Arias H, Pimplikar S, Ghosal K, Murakami K, Irie K, Ohigashi H, Hara H, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T, Tong Y, Zhou W, Fung V, Christensen M, Qing H, Sun X, Song W, Puertas M, Martinez-Martos J, Cobo M, Carrera M, Mayas M, Ramirez-Exposito M, Venkateshappa C, Harish G, Mahadevan A, Bharath MS, Shankar S, Maes M, Kubera M, Obuchowiczwa E, Goehler L, Brzeszcz J, Maes M, Ringel K, Kubera M, Berk M, Rybakowski J, Maes M, Mihaylova I, Leunis J, Maes M, Kubera M, Mihaylova I, Geffard M, Galecki P, Leunis J, Berk M, Maes M, Eaton W, Pedersen M, Nielsen P, Mortensen P, Fontaine L, de la Schwarz M, Riedel M, Dehning S, Douhet A, Spellmann I, Kleindienst N, Zill P, Plischke H, Gruber R, Muller N, Margutti P, Delunardo F, Ortona E, Ganzinelli S, Borda E, Sterin-Borda L, Strous R, Shoenfeld Y, Hillegers M, Reichart C, Wals M, Verhulst F, Ormel J, Nolen W, Drexhage HH, Vonk R, Schot A, van der Kahn R, Nolen W, Drexhage HH, Kupka R, Nolen W, Post R, McElroy S, Altshuler L, Denicoff K, Frye M, Keck P, Leverich G, Rush A, Suppes T, Pollio C, Drexhage HH, Padmos R, Bekris L, Knijff E, Tiemeier H, Kupka R, Cohen D, Nolen W, Lernmark A, Drexhage HH, Rothermundt M, Arolt V, Weitzsch C, Eckhoff D, Kirchner H, Drexhage R, Hoogenboezem TT, Cohen D, Versnel M, Nolen W, Beveren N, van Drexhage HH, Zorrilla E, Cannon T, Gur R, Kessler J, Drexhage R, Hoogenboezem TT, Versnel M, Berghout A, Nolen W, Drexhage HH, Steiner J, Bielau H, Brisch R, Danos P, Ullrich O, Mawrin C, Bernstein H, Bogerts B, Bayer T, Buslei R, Havas L, Falkai P, Radewicz K, Garey L, Gentleman S, Reynolds R, Wierzba-Bobrowicz T, Lewandowska E, Lechowicz W, Stepien T, Pasennik E, Falke E, Han L, Arnold S, Arnold S, Trojanowski J, Gur R, Blackwell P, Han L, Choi C, Togo T, Akiyama H, Kondo H, Ikeda K, Kato M, Iseki E, Kosaka K, Steiner J, Walter M, Gos T, Guillemin G, Bernstein H, Sarnyai Z, Mawrin C, Brisch R, Bielau H, Schwabedissen LM, zu Bogerts B, Myint A, Cosenza-Nashat M, Zhao M, Suh H, Morgan J, Natividad R, Morgello S, Lee S, Doorduin J, Vries E, de Dierckx R, Klein H, Doorduin J, Vries E, de Willemsen A, Groot J, de Dierckx R, Klein H, Hammoud D, Endres C, Chander A, Guilarte T, Wong D, Sacktor N, McArthur J, Pomper M, Vries E, de Dierckx R, Klein H, Grover V, Pavese N, Koh S, Wylezinska M, Saxby B, Gerhard A, Forton D, Brooks D, Thomas H, Taylor-Robinson S, Leong D, Le O, Oliva L, Butterworth R, Butterworth R, Wisor J, Schmidt M, Clegern W, Ekdahl C, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O, Roumier A, Pascual O, Bechade C, Wakselman S, Poncer J, Real E, Triller A, Bessis A, Costello D, Lyons A, Denieffe S, Browne T, Cox F, Lynch M, Roumier A, Bechade C, Poncer J, Smalla K, Tomasello E, Vivier E, Gundelfinger E, Triller A, Bessis A, Liu Y, Lin H, Tzeng S, Patterson P, Maes M, Fisar Z, Medina M, Scapagnini G, Nowak G, Berk M, Anderson G, Maes M, Maes M, Chan M, Moore A, Gallagher P, Castro V, Fava M, Weilburg J, Murphy S, Gainer V, Churchill S, Kohane I, Iosifescu D, Smoller J, Perlis R, Asadabadi M, Mohammadi M, Ghanizadeh A, Modabbernia A, Ashrafi M, Hassanzadeh E, Forghani S, Akhondzadeh S, Abbasi S, Hosseini F, Modabbernia A, Ashrafi M, Akhondzadeh S, Borgeat P, Naccache P, Maderna P, Godson C, Gao X, Adhikari C, Peng L, Guo X, Zhai Y, He X, Zhang L, Lin J, Zuo Z, Goldstein S, Leung J, Silverstein D, Sun X, Han F, Yi J, Han L, Wang B, Zhu G, Cai J, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Xu B, Kutuk O, Basaga H, Ikonomidis I, Andreotti F, Economou E, Stefanadis C, Toutouzas P, Nihoyannopoulos P, Endres S, Whitaker R, Ghorbani R, Meydani S, Dinarello C, Moon H, Tae Y, Kim YY, Jeon SG, Oh S, Gho YS, Zhu Z, Kim YY, Galecki P, Galecka E, Maes M, Chamielec M, Orzechowska A, Bobinska K, Lewinski A, Szemraj J, Galecki P, Florkowski A, Bienkiewicz M, Szemraj J, Minghetti L, Minghetti L, Gilroy D, Stables M, Newson J, Gu X, Long C, Sun L, Xie C, Lin X, Cai H, Aid S, Langenbach R, Bosetti F, Vane J, Carnovale D, Fukuda A, Underhill D, Laffan J, Breuel K, Miguel LS, de Frutos T, de González-Fernández F, Pozo V, del Lahoz C, Jiménez A, Rico L, García R, Aceituno E, Millás I, Gómez J, Farré J, Casado S, López-Farré A, Farivar R, Chobanian A, Brecher P, Nishio E, Watanabe Y, Cristobal J, De Madrigal J, Lizasoain I, Lorenzo P, Leza J, Moro M, Mendlewicz J, Kriwin P, Oswald P, Souery D, Alboni S, Brunello N, Almeida O, Alfonso H, Jamrozik K, Hankey G, Flicker L, Galecki P, Szemraj J, Bienkiewicz M, Zboralski K, Galecka E, Savitz J, Preskorn S, Teague T, Drevets D, Yates W, Drevets W, Laan W, Grobbee D, Selten J, Heijnen C, Kahn R, Burger H, Nilsson S, Johansson B, Takkinen S, Berg S, Zarit S, McClearn G, Melander A, Jaturapatporn D, Isaac M, McCleery J, Tabet N, Pomponi M, Gambassi G, Pomponi M, Masullo C, Raison C, Rutherford R, Woolwine B, Shuo C, Schettler P, Drake D, Haroon E, Miller A, Almeida O, Flicker L, Yeap B, Alfonso H, McCaul K, Hankey G. Aspirin: a review of its neurobiological properties and therapeutic potential for mental illness. BMC Med. 2013;11:74. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolini P, Catalani A, Zuena AR, Angelucci L. Inhibition of COX-2 reduces the age-dependent increase of hippocampal inflammatory markers, corticosterone secretion, and behavioral impairments in the rat. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:337–343. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano P, Bui E, Rogers AH, Walton ZE, Ross R, Zeng M, Nadal-Vicens M, Mischoulon D, Baker AW, Keshaviah A, Worthington J, Hoge EA, Alpert J, Fava M, Wong KK, Simon NM. Inflammatory cytokines in major depressive disorder: A case-control study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0004867416652736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher D, Kiss A, Lanctot K, Herrmann N. Depression with inflammation: longitudinal analysis of a proposed depressive subtype in community dwelling older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1002/gps.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh A, Hedayati A. Augmentation of citalopram with aspirin for treating major depressive disorder, a double blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Antiinflamm. Antiallergy. Agents Med Chem. 2014 doi: 10.2174/1871523013666140804225608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus J, Vandeleur CL, Lasserre AM, Strippoli MPF, Castelao E, Gholam-Rezaee M, Waeber G, Aubry JM, Vollenweider P, Preisig M. Aspirin and statin use and the subsequent development of depression in men and women: Results from a longitudinal population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2015;182:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander D. Intestinal permeability, leaky gut, and intestinal disorders. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999;1:410–6. doi: 10.1007/s11894-999-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, Motiwala SR, Januzzi JL. Depression and cardiac disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/695925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Cristiano, Freitas Thiago, Maes M, de Andrade Nayanna, Liu Celina, Fernandes Brisa, Stubbs Brendon , Solmi Marco, Veronese N, Herrmann Nathann, Raison Charles, Miller Brian, Lanctôt Krista, Carvalho AF. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression:a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acps.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler O, ME B, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1381–1391. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12:277–87. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M. Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in depression is not a viable therapeutic approach and may even aggravate the pathophysiology underpinning depression. Metab Brain Dis. 2012;27:405–413. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maske UE, Buttery AK, Beesdo-Baum K, Riedel-Heller S, Hapke U, Busch MA. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV-TR major depressive disorder, self-reported diagnosed depression and current depressive symptoms among adults in Germany. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlewicz J, Kriwin P, Oswald P, Souery D, Alboni S, Brunello N. Shortened onset of action of antidepressants in major depression using acetylsalicylic acid augmentation: a pilot open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:227–231. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na KS, Lee KJ, Lee JS, Cho YS, Jung HY. Efficacy of adjunctive celecoxib treatment for patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.09.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai Y, Inoue T, Toda H, Toyomaki A, Nakato Y, Nakagawa S, Kitaichi Y, Kameyama R, Hayashishita Y, Wakatsuki Y, Oba K, Tanabe H, Kusumi I. Corrigendum to: “The influence of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events and temperaments on depressive symptoms in the nonclinical general adult population”. J Affect Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson SE, Johansson ÆB, Takkinen ÆS. Does aspirin protect against Alzheimer ’ s dementia ? A study in a Swedish population-based sample aged ‡ 80 years. 2003:313–319. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0618-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi C, Santarella L, Costa MG, Manfrini O, Flacco ME, Capasso L, Chiarini S, Di Baldassarre A, Manzoli L. Pathophysiological mechanisms linking depression and atherosclerosis: An overview. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26:775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahola JG. Somatic Drugs for Psychiatric Diseases: Aspirin or Simvastatin for Depression? Curr Neuropharmacol. 2012;10:139–158. doi: 10.2174/157015912800604533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport M, Nierenberg A, Schettler P, Kinkead B, Cardoos A, Walker R, Mischoulon D. Inflammation as a predictive biomarker for response to omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder: a proof-of-concept study. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;21:71–79. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1741–1750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salagre E, Fernandes BS, Dodd S, Brownstein DJ, Berk M. Statins for the treatment of depression: A meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp LK, Lipsky MS. Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1001–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slyepchenko A, Maes M, Jacka FN, Köhler CA, Barichello T, Mcintyre RS, Berk M, Grande I, Foster JA, Vieta E, Carvalho AF. Gut Microbiota, Bacterial Translocation, and Interactions with Diet: Pathophysiological Links between Major Depressive Disorder and Non-Communicable Medical Comorbidities. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;8686:31–4631. doi: 10.1159/000448957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M, Veronese N, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Manzato E, Sergi G, Correll CU. Inflammatory cytokines and anorexia nervosa: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:237–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, Papadopoulos A, Herane Vives A, Cleare AJ. Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:1532–43. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:963–74. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemeier H, Van Dijck W, Hofman A, Witteman JCM, Stijnen T, Breteler MMB. Relationship between atherosclerosis and late-life depression: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:369–376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane JR, Botting RM. The mechanism of action of aspirin. Thrombosis Research. 2003:255–258. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij MW, Haag MDM, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Stricker BH, Breteler MMB. Use of antithrombotic drugs and the presence of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:714–720. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese N, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Smith TO, Noale M, Cooper C, Maggi S. Association between lower limb osteoarthritis and incidence of depressive symptoms: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Age Ageing. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LJ, Pasco JA, Mohebbi M, Jacka FN, Stuart AL, Venugopal K, O’Neil A, Berk M. Statin and Aspirin Use and the Risk of Mood Disorders among Men. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw008. pyw008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.