Abstract

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging of amides at 3.5 ppm and fast exchanging amines at 3 ppm provides a unique means to enhance the sensitivity for detecting e.g., proteins/peptides and neurotransmitters, respectively, and hence can provide important information on molecular composition. However, despite the high sensitivity compared to conventional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), CEST in practice often has relatively poor specificity. For example, CEST signals are typically influenced by several confounding effects including direct water saturation (DS), semi-solid non-specific magnetization transfer (MT), the influence of water relaxation times (T1w) and nearby overlapping CEST signals. Although several editing techniques have been developed to increase the specificity by removing DS, semi-solid MT, and T1w influences, it is still challenging to remove overlapping CEST signals from different exchanging sites. For instance, the amide proton transfer (APT) signal could be contaminated by CEST effects from fast exchanging amines at 3 ppm and intermediate exchanging amines at 2 ppm. The current work applies an exchange-dependent relaxation rate (Rex) to address this problem. Simulations demonstrate that: (1) slowly exchanging amides and fast exchanging amines have distinct dependences on irradiation powers; and (2) Rex serves as a resonance-frequency high-pass filter to selectively reduce CEST signals with resonance frequencies closer to water. These characteristics of Rex provide a means to isolate the APT signal from amines. In addition, previous studies have shown that CEST signals from fast exchanging amines have no distinct features around their resonance frequencies. However, Rex gives Lorentzian lineshapes centered at their resonance frequencies for fast exchanging amines and thus can significantly increase the specificity of CEST imaging for amides and fast exchanging amines.

Keywords: MRI, CEST, APT, fast exchanging amine, specificity

Graphical abstract

We applied an exchange-dependent relaxation rate Rex to enhance CEST specificity for imaging amide and fast exchanging amine protons. Results show that Rex can correct the shift of CEST peaks in the CEST imaging of fast exchanging amines, and the subtraction of two Rex with a low and a high power (ΔRex) can successfully remove influences from nearby CEST signals in APT imaging.

INTRODUCTION

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) is a MRI contrast mechanism for indirectly detecting low-concentration solute molecules with enhanced sensitivity by saturating the solute protons and measuring subsequent changes in the water signal (1). Previously, CEST has been used to detect various endogenous metabolites and macromolecules, such as proteins/peptides (2), creatine (3–6), glutamate (7–12), glucose (13–16), myo-inositol (17), glycogen (18), glycosaminoglycan (19), and lactate (20). Some CEST effects are also sensitive to proton chemical exchange rates and pH (2,21,22). Amide proton transfer (APT) is one widely used form of CEST effect arising from protein backbone amides which resonate at 3.5 ppm from water, and has been used in a range of applications including studies of solid tumors (23–27), ischemic stroke (28–31), and multiple sclerosis (32). Recently, CEST imaging of fast exchanging amines has also been reported. This CEST effect is centered at around 3 ppm from the water resonance which may originate from glutamate amine (7,33) and protein lysine amine (34,35) protons, and which has potential applications in neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (8,9), Huntington’s disease (10), epilepsy (11), psychosis spectrum (36), and dopamine deficiency (12).

However, although CEST significantly increases the sensitivity for detecting metabolites compared to magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), its specificity in practice is relatively poor: first, CEST can be diminished by non-specific background effects including direct water saturation (DS) and semi-solid magnetization transfer (MT) effects; second, CEST signals may depend on longitudinal relaxation time constant of water (T1w); third, CEST signals from different molecular species overlap. These non-specific factors often vary in pathological tissues, and thus reduce the specificity of CEST for imaging molecular composition. The development of methods to enhance the specificity of CEST imaging is thus important for practical applications.

In order to identify the effect of exchange at a specific frequency, CEST imaging usually acquires a Z-spectrum by employing RF irradiation pulses over a certain range of frequencies, and the normalized water signals are then analyzed as a function of irradiation frequency (37). Previously, several approaches have been developed to process Z-spectra to isolate the CEST effects from other non-specific signals. For example, an asymmetric analysis (MTRasym) of the Z-spectrum has been used to remove non-specific background signals by assuming that they are symmetric about water. However, in biological tissues, the semi-solid MT is asymmetric, and there are also upfield, relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE) effects (38). Therefore, MTRasym does not accurately report specific information on composition, so to avoid some of these confounding factors, other approaches such as, an extrapolated semi-solid MT reference (EMR) approach (39–41), a Lorentzian difference (LD) analysis (42,43), and a three-point method (21,44) etc. have been developed. To further increase the specificity of CEST metrics, an inverse subtraction method that takes account of variations in T1w, named apparent exchange-dependent relaxation (AREX), was also developed (45–47). Distinct from conventional subtractions of reference and label signals, which can remove only some non-specific background signals, this inverse subtraction can remove a broader range of interactions between CEST and background signals (45).

However, despite these improvements, it is still challenging to remove overlapping CEST signals from nearby exchanging sites. In APT imaging, which is usually performed at relatively low irradiation powers (e.g. 1 μT), nearby intermediate-exchanging amines at 2 ppm may contribute to CEST effects at 3.5 ppm. In addition, our previous study (48) showed that the contributions of fast exchanging amines to CEST signals at 3 ppm are significant even at low irradiation powers, which affect a broad spectral region that overlaps with the APT spectrum centered around 3.5 ppm. Although a multiple-pool Lorentzian fit may potentially separate such overlapping signals (49–53), our study (48) also indicated that fast exchanging amines do not produce Lorentzian lineshapes in CEST spectra, which induces errors to spectral fittings. In CEST imaging of fast exchanging amines, which is usually performed at relatively high irradiation powers (e.g. > 3 μT), the CEST peak shifts, which makes it difficult to identify specific CEST effects (7,54).

In this paper, we apply an exchange-dependent relaxation rate (Rex) for quantifying CEST effects to overcome some of these limitations. Rex was first introduced by Trott and Palmer (55), and later Jin et al. (56) showed that Rex can be obtained from CEST Z-spectra in simple model (solute and water) phantoms. More recently, Zaiss et al. (45–47) defined a slightly different Rex and showed that this Rex can be obtained from AREX and can be applied in more complex model (solute, semi-solid component, and water) systems and in vivo. Note that these two definitions of Rex can be exchangeable with a factor (square of irradiation power/square of irradiation frequency offset). In the rest of this article, we name Rex defined by Zaiss et al. as R′ex to avoid any confusion. Since AREX is more suitable to process in vivo CEST data, we obtain Rex from the AREX metric by accounting for the irradiation power. The Rex reduces the influences of overlapping CEST signals for APT imaging and provides Lorentzian lineshapes centered at their resonance frequencies (56) for fast exchanging amines, and thus can significantly enhances the CEST detection specificity compared with several previous quantification methods (21,38–40,42–44).

METHODS

The magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) is here defined as the difference between a labelled signal (Slab(Δω)) and a reference signal (Sref(Δω)) normalized by a control signal (S0) (37),

| (1) |

where Δω is the RF frequency offset from the water resonance frequency.

The metric AREX was defined as (47),

| (2) |

where

R1obs is the apparent water longitudinal relaxation rate, fm is the semi-solid component concentration, and ω1 is the irradiation power.

R′ex(Δω) for fast exchanging pools can be described by (57),

| (3) |

where fs is the solute concentration, ksw is the exchange rate between solute and water protons, δωs is the difference between the water and solute resonance frequencies, and R2s is the solute transverse relaxation rate. The ‘a-peak’ is close to 1 when the irradiation pulse is near the solute resonance frequency, and thus it has weak influence on CEST signals with narrow peaks which could be from slow exchanging pools (e.g. amide) and intermediate exchanging pools (e.g. amine at 2 ppm) at low ω1. For this reason, the slow and intermediate exchanging pools, that have been described by following Eq. (4), could be also roughly described by Eq. (3).

| (4) |

Note that Eq. (4) is a Lorentzian function, whereas Eq. (3) is not.

Here, we normalize AREX by the irradiation power expressed as the square of tan θ, where tan2θ = ω12/Δω2.

| (5) |

Eq. (5) shows that after normalization by the square of tangent theta, Rex can be obtained from AREX. CEST lineshapes in Eq. (5) are Lorentzian for both slow and fast exchanging regimes. Specifically, for slow exchanging amide pools for which ksw (e.g. 30 s−1 (2)) is much less than typical ω1 (e.g. 1 μT (44,48,52,58,59)), Rex inversely depends on ω12 and is expected to approach 0 at high ω1; by contrast, for fast exchanging pools for which ksw (e.g. 5000 s−1 (7,33–35)) is much greater than ω1 (e.g. 3.6 μT (7)), Rex is approximately independent of ω12. This is different from AREX which gradually increases at higher ω1 for slow exchanging pools, and is proportional to ω12 for fast exchanging pools. These characteristics of Rex provide an opportunity to isolate slow exchanging amide protons from fast exchanging amine signals. The subtraction of Rex acquired at a high ω1 from that at a low ω1 yields.

| (6) |

The contributions from fast exchanging pools are relatively independent of irradiation powers, and hence are removed in the subtraction. Therefore, ΔRex provides a means to detect slow exchanging pools selectively. In addition, both Rex and ΔRex are proportional to δωs2, which serves as a resonance-frequency high-pass filter to reduce the influences of other CEST signals with resonance frequency closer to water. This in turn enhances the detection of APT at the higher frequency offset 3.5 ppm. Because MTR, AREX, Rex and ΔRex were obtained by several ways including simulations and fitting simulated or measured Z-spectra, different subscripts were used to distinguish the obtaining methods.

Numerical simulations

Two types of numerical simulations were performed. First, in order to study the different dependences on ω1 and Δω of slow and fast exchanging pools, simulations of two-pool (amide and water or fast exchanging amine and water) models and one-pool (water) model were performed. The two-pool model simulations were used to create labelled signals, and the one-pool model simulations were used to create reference signals for further quantification. The corresponding metrics are named MTRsimu, AREXsimu, and Rex_simu respectively. Second, to mimic realistic tissues, simulations were performed of a six-pool (amide, intermediate and fast exchanging amines, water, rNOE, and semi-solid component) model and another two-pool (semi-solid component and water) model. The six-pool model simulations were used to create labelled signals, and the two-pool (semi-solid component and water) model simulations were used to create simulated reference signals. Fitted reference signals were also obtained from the following fitting approaches on the six-pool model simulated Z-spectra. Comparisons between the fitted reference signals and the simulated reference signals were performed to evaluate the fitting accuracy. The sequence parameters for the simulations are the same as those used in MR experiments in vivo (see below), and the tissue parameters are tabulated in Table 1. R1obs was obtained by using Eq. (7) according to Ref (47),

Table 1.

Parameters for the multiple model numerical simulations with pool concentration (f), exchange rate (k), longitudinal relaxation time (T1), transverse relaxation time (T2), and resonance frequency offset for each pool (δω). Water content is set to be 1.

| water | amide | intermediate exchanging amine | fast exchanging amine | NOE(−3.5) | Semi-solid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | 1 | 0.001,0.0015, 0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.0025, 0.005, 0.0075 | 0.005 | 0.06,0.09, 0.12 |

| K (s−1) | - | 30, 50, 70 | 500 | 3000, 5000, 7000 | 25 | 15, 25, 35 |

| T1 (s) | 1, 1.5, 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| T2 (ms) | 40, 60, 80 | 2 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 0.015 |

| δω (ppm) | 0 | 3.5 | 2 | 3 | −3.5 | −2.3a |

Ref (68)

| (7) |

where R1w=1/T1w and R1m is the semi-solid component longitudinal relaxation rate.

The coupled Bloch equations can be written as , where A is a matrix for the corresponding model. The components of the water and solute magnetizations are each described by three coupled equations. The semi-solid pool has a single coupled equation representing the z component, with a Lorentzian absorption lineshape (49). All numerical calculations of the CEST signals were obtained by integrating the differential equations through the sequence using the ordinary differential equation solver (ODE45) in MATLAB 2013b (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Animal preparation

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee of Vanderbilt University. Five healthy rats were included in this study. All rats were immobilized and anesthetized with a 2%/98% isoflurane/oxygen mixture during data acquisition. Respiration was monitored to be stable, and a constant rectal temperature of 37°C was maintained throughout the experiments using a warm-air feedback system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY, USA).

MRI

All measurements were performed using a Varian DirectDrive™ horizontal 9.4T magnet with a 38-mm Litz RF coil (Doty Scientific Inc. Columbia, SC, USA). CEST measurements were performed by applying a continuous wave (CW) irradiation with irradiation duration of 5 s and ω1 of 1 μT and 3.6 μT before acquisition. Since AREX can only process steady-state CEST signals (45), the 5 s irradiation is performed to ensure that the spin system goes to steady state. Z-spectra with ω1 of 1 μT were acquired with Δω from −4000 Hz to −2500 Hz with a step size of 500 Hz (−10 ppm to −6.25 ppm with a step size of 1.25 ppm at 9.4 T), −2000 Hz to 2000 Hz with a step size of 50 Hz (−5 ppm to 5 ppm with a step size of 0.125 ppm at 9.4 T), and 2500 Hz to 4000 Hz with a step size of 500 Hz (6.25 ppm to 10 ppm with a step size of 1.25 ppm at 9.4 T). Z-spectra with ω1 of 3.6 μT were acquired with Δω from −6500 Hz to −3500 Hz with a step size of 500 Hz (−16.25 ppm to −8.75 ppm with a step size of 1.25 ppm at 9.4 T), −2000 Hz to 2000 Hz with steps of 50 Hz (−5 ppm to 5 ppm with a step size of 0.125 at 9.4 T), and 3500 Hz to 6500 Hz with a step size of 500 Hz (8.75 ppm to 16.25 ppm with a step size of 1.25 at 9.4 T). Control images were acquired with Δω of 100,000 Hz (250 ppm at 9.4 T). The acquisition of a Z-spectrum for each power takes roughly 20 mins. R1obs and fm were obtained using a selective inversion recovery (SIR) quantitative MT method (60). Specifically, a 1-ms inversion hard pulse was applied to invert the free water pool and the subsequent longitudinal recovery times were set to be 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20, 50, 200, 500, 800, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 6000 ms. Spin-echo Echo Planar Imaging (SE-EPI) was used for the readout followed by a saturation pulse train to shorten the total acquisition time as described previously (61). A constant delay time of 3.5 s was set between the saturation pulse train and the next inversion pulse. The SIR quantitative MT takes roughly 6 mins. Before data acquisition, shimming was carefully performed so that the root mean square (RMS) deviation of B0 was less than 5 Hz. All images were obtained using a single-shot SE-EPI acquisition with triple references for phase correction and matrix size 64 × 64 and field of view 30 mm × 30 mm.

Data analysis

For six-pool model simulations and experiments, to avoid the effects of rNOE and asymmetric MT, we used the EMR method (39–41) to fit reference signals for quantifying CEST signals, and derived the metrics as MTREMR, AREXEMR, Rex_EMR, and ΔRex_EMR, respectively. Specifically for the EMR, CEST data with Δω from −6500 Hz to −3500 Hz and 3500 Hz to 6500 Hz and ω1 of 3.6 μT, and with Δω from −4000 Hz to −2500 Hz and 2500 Hz to 4000 Hz and ω1 of 1.0 μT were fitted to a two-pool MT model (APPENDIX) (54). The reference signals in an offset range from −5 ppm to 5 ppm were then estimated using the fitted parameters and used for calculating the above metrics. Due to the relatively homogenous B1 field in rat brains, ω1 used to calculate the tangent theta were from nominal values. We also used the three-point method to quantify APT signals and the asymmetric analysis method to quantify CEST signals from fast exchanging amines, and compared them with EMR. Specifically, the average of two CEST signals at 3 and 4 ppm in Z-spectrum was used as reference signal for the three-point method and the signal on the opposite site of water was used as reference signal for the asymmetric analysis method. Their corresponding Rex metrics were named Rex_3pt and Rex_asym, respectively. To evaluate the accuracy of Rex from these approaches, Rex for amide, fast exchanging amine, and the sum of three pools (amide, intermediate and fast exchanging amine) were also calculated using Eq. (5) and used as standard values. For animal studies, region of interests (ROIs) were chosen from the whole rat brains. All data analyses were performed using MATLAB 2013b (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

RESULTS

Simulated MTR, AREX, and Rex for slow exchanging amides and fast exchanging amines

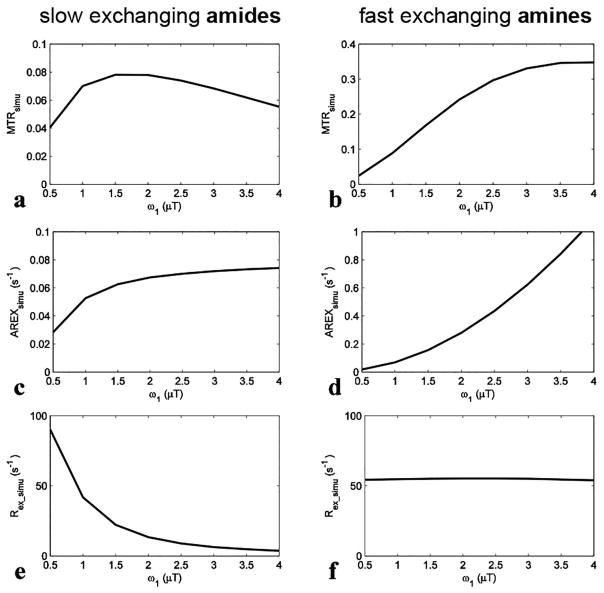

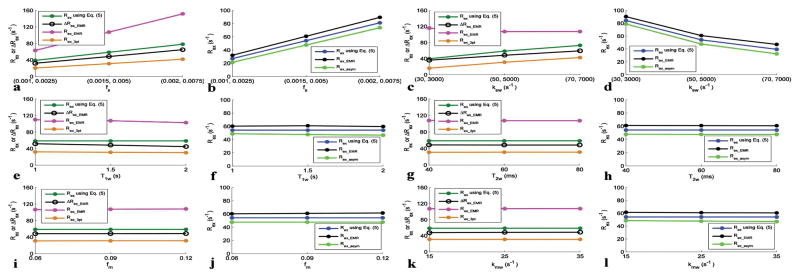

We got MTRsimu, AREXsimu, and Rex_simu with different ω1 and Δω using the two-pool (amide and water or fast exchanging amine and water) model simulations, and results are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively. For slow exchanging amides, MTRsimu (Fig. 1a) increases with ω1 when it is smaller than 1.5 μT, and decreases at higher ω1. This non-monotonic dependence may be caused the competitive effects of ω1 and DS. After correcting for the DS effect by the inverse analysis, AREXsimu (Fig. 1c) increases continuously with ω1. Different from both MTRsimu and AREXsimu, Rex_simu (Fig. 1e) for slow exchanging amides decreases significantly with ω1 (Rex_simu value at 3.5 μT is roughly 10% of that at 1 μT). For fast exchanging amines, both MTRsimu (Fig. 1b) and AREXsimu (Fig. 1d) increase with ω1 in our simulation range. In contrast, Rex_simu (Fig. 1f) of fast exchanging amines is independent of ω1. This simulation result is in agreement with the predictions of Eq. (5), and demonstrates that the subtraction of the two Rex values acquired with a high and a low ω1 may remove the influence of fast exchanging amines in APT imaging.

FIG. 1.

Simulated MTRsimu, AREXsimu, and Rex_simu values at 3.5 ppm for slow exchanging amides (a, c, and e) and at 3 ppm for fast exchanging amines (b, d, and f), respectively, vs. ω1. ω1 is the irradiation power. The parameters used in simulation were shown in bold in Table 1.

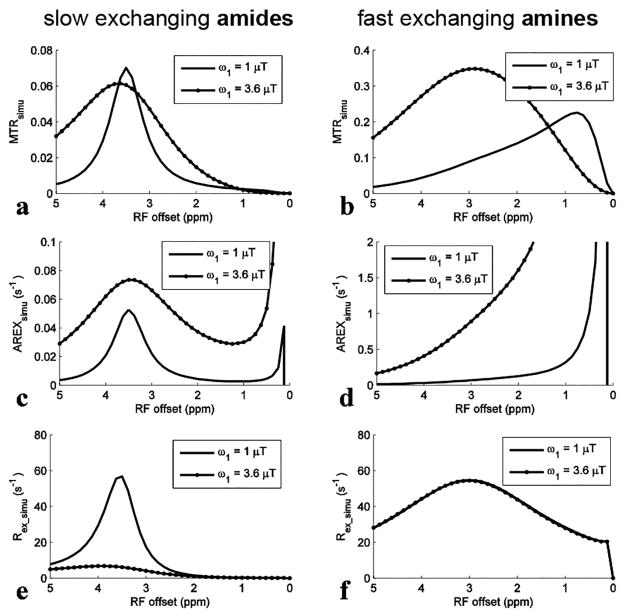

FIG. 2.

Simulated MTRsimu, AREXsimu, and Rex_simu spectra for slow exchanging amides (a, c, and e) and for fast exchanging amines (b, d, and f), respectively, with ω1 of 1 μT and 3.6 μT. The parameters used in simulation were shown in bold in Table 1.

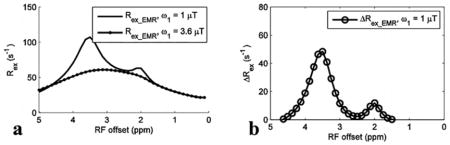

Fig. 2 shows the spectra of these metrics. For slow exchanging amides with ω1 of 1 μT, the deviation of the Rex_simu peak lineshape (Fig. 2e) caused by the tangent theta normalization is negligible compared with the MTRsimu peak lineshape (Fig. 2a) and the AREXsimu peak lineshape (Fig. 2c). This result is in agreement with our analysis that the ‘a-peak’ does not influence CEST peaks of slow and intermediate exchanging pools greatly, and thus Eq. (3) can model CEST peaks of slow to fast exchanging pools. For fast exchanging amines, both the central frequency and the lineshape of MTRsimu peaks (Fig. 2b) depend on ω1, suggesting that MTR may misinterpret CEST effects. This agrees with previous reports that MTRasym peaks for fast exchanging pools depend on multiple sequence parameters and cannot be used to identify an effect of exchange at a specific frequency (40,46). Even using AREX to improve specificity (Fig. 2d), the CEST peaks have no distinct features around their resonance frequency offsets. In contrast, Rex_simu peaks (Fig. 2f) have Lorentzian lineshapes centered at 3 ppm without dependence on ω1.

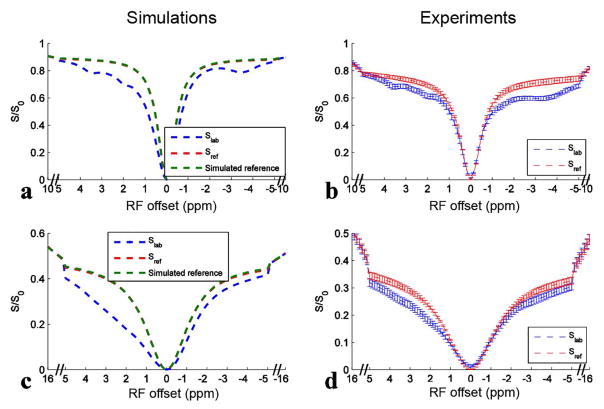

Fitting references using EMR

Fig 3 shows results of simulating the six-pool model and the measured Z-spectra from rat brains and their corresponding EMR fitted reference spectra with ω1 of 1 μT and 3.6 μT. The simulated reference spectra using two-pool (semi-solid component and water) model simulations are also provided in Fig. 3a and 3c. The match of the fitted reference spectra (Sref) and the simulated reference spectra indicates the success of the fitting approach. In Fig. 3b and 3d, the match of the Z-spectra and the corresponding fitted reference spectra beyond 5 ppm and −5 ppm also suggests the success of the fitting approach in animals (Sup. Fig. S1 shows that the residuals of the EMR fitting are very small). Table 2 lists the fitted semi-solid MT parameters and simulation parameters in the six-pool model simulations. Note that the fitted parameters are very close to the simulation parameters. Table 3 lists the fitted semi-solid MT parameters in the animal experiments.

FIG. 3.

Six-pool (amide, intermediate exchanging amine, fast exchanging amine, rNOE, semi-solid MT, and water) model simulated Z-spectra (Slab) and corresponding EMR fitted reference spectra (Sref) (a, c) using values in bold in Table 1, and experimental Z-spectra (Slab) and corresponding EMR fitted reference spectra (Sref) on five healthy rat brains (b, d) with ω1 of 1 μT (a, b) and 3.6 μT (c, d), respectively. Two-pool (water and semi-solid component) model simulated reference spectra were also shown in (a, c) for comparison with Sref spectra. Note that Sref spectra are covered by the simulated reference spectra, indicating the success of the fitting approach. Error bars in (b, d) represent the standard deviations across subjects.

Table 2.

Fitted semi-solid MT parameters and the simulation parameters in the six-pool model simulations using values in bold in Table 1.

| kmw (s−1) | T2m (μs) | kmwfmT1w | δωm (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitted | 26.9833 | 16.423 | 3.5466 | −2.0315 |

| simulation | 25 | 15 | 3.375 | −2.3 |

Table 3.

Fitted semi-solid MT parameters for the whole brain in the animal experiments.

| n=5 | kmw (s−1) | T2m (μs) | kmwfmT1w | δωm (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitted | 17.5 ± 3.1 | 41 ± 4.1 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | −1.4 ± 0.1 |

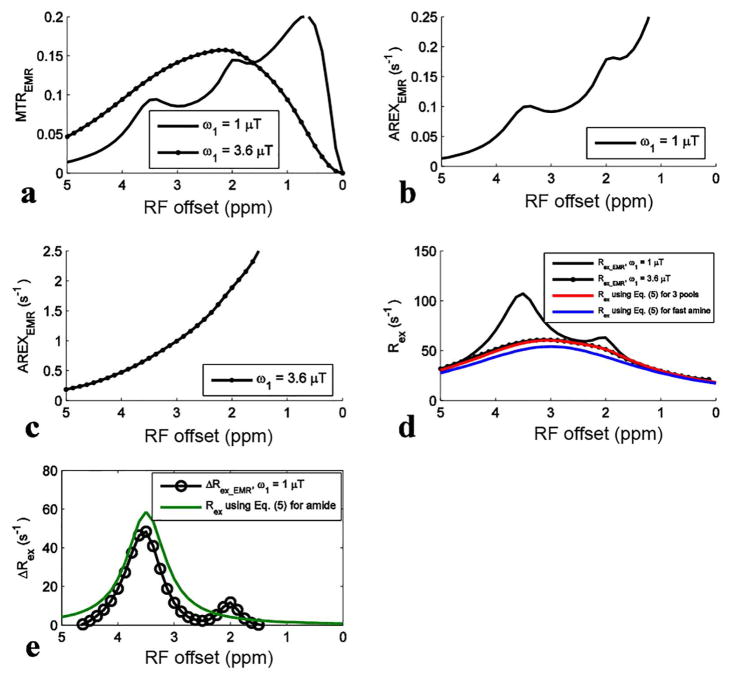

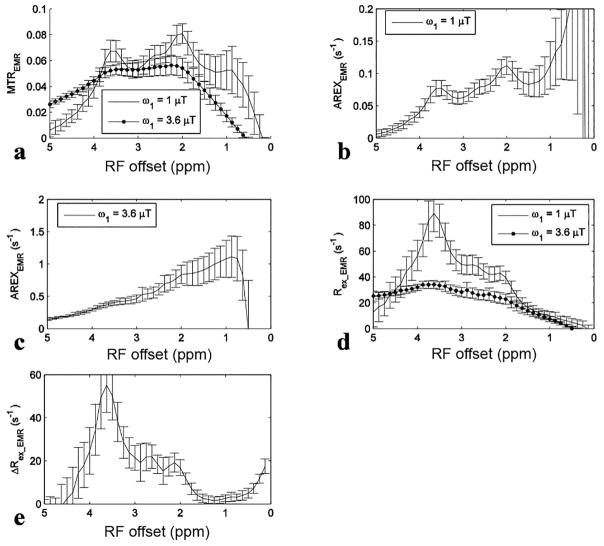

Fitted MTR, AREX, Rex, and ΔRex from simulated Z-spectra with the presence of multiple exchanging pools

For simulations with ω1 of 1 μT, the APT signal at 3.5 ppm in the MTREMR spectrum (Fig. 4a) overlaps with nearby CEST signals. These nearby overlapping signals are still present in the AREXEMR spectrum (Fig. 4b). However, the intermediate exchanging amine signal at 2 ppm becomes relatively weak in the Rex_EMR spectrum (Fig. 4d) and the ΔRex_EMR spectrum (Fig. 4e). This result is also in agreement with the expectation from Eq. (5) that Rex has a resonance-frequency high-pass filter effect. Fig. 4d shows that the Rex_EMR spectrum with ω1 of 3.6 μT roughly matches the baseline of that with ω1 of 1 μT. Fig. 4e shows the ΔRex_EMR spectrum in which both the nearby intermediate exchanging amine at 2 ppm and the fast exchanging amine at 3 ppm are successfully reduced. Fig. 4d also shows that Rex_EMR spectrum is a Lorentzian lineshape centered at its resonance frequency and roughly matches the calculated Rex using Eq. (5) for the sum of three pools (amide, intermediate exchanging amine, and fast exchanging amine). The difference between Rex using Eq. (5) for the sum of three pools and the fast exchanging amine pool is the contributions from the amide and the intermediate exchanging amine which cause ~11% error for quantifying the fast exchanging amine. Fig. 4e also shows that Rex_EMR has ~17% error for quantifying amide compared with Rex using Eq. (5) for amide. Similar conclusion can be also drawn from simulations with other tissue parameters listed in Table 1 (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Fitted MTREMR (a), AREXEMR for slow exchanging amides (b), AREXEMR for fast exchanging amines (c), Rex_EMR (d), and ΔRex_EMR (e) spectra from the six-pool model simulations using values in bold in Table 1. Calculated Rex using Eq. (5) for the sum of three pools (amide, intermediate exchanging amine, and fast exchanging amine) and fast exchanging amine and Rex using Eq. (5) for amide were also shown in (d) and/or (e), for comparison with the fitted metrics.

Fig. 5 shows several Rex metrics and/or ΔRex metric with varied tissue parameters. Note that Rex_EMR is significantly larger than Rex using Eq. (5), but Rex_3pt is significantly smaller than Rex using Eq. (5) for slow exchanging amides. However, ΔRex_EMR is more close to Rex using Eq. (5) than other two metrics. Also note that both Rex_EMR and Rex_asym are close to Rex using Eq. (5) for fast exchanging amines, although Rex_EMR is larger and Rex_asym is smaller than Rex using Eq. (5).

Fig. 5.

Rex and/or ΔRex with varied amide and fast exchanging amine concentrations (a, b), amide-water and fast exchanging amine-water exchange rates (c, d), T1w (e, f), T2w (g, h), fm (i, j), and kmw (k, l). Each set of parameters was varied with other parameters remaining at the values in bold in Table 1. 1 μT and 3.6 μT powers are used for getting Rex for slow exchanging amides and fast exchanging amines, respectively.

Experimental MTR, AREX, Rex, and ΔRex

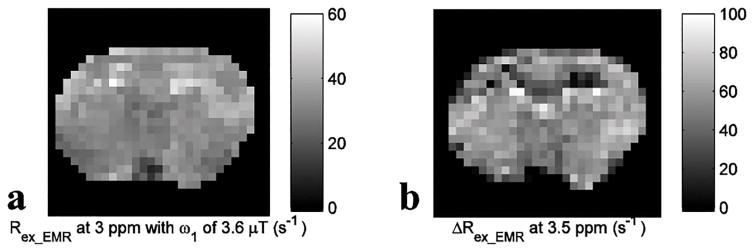

Fig. 6 shows experimental results from rat brains. Similar to the simulations in Fig. 4, the APT signal at 3.5 ppm acquired with ω1 of 1 μT overlaps with nearby CEST signals in the MTREMR spectrum (Fig. 6a), but can be successfully isolated from nearby CEST signals in the ΔRex_EMR spectrum (Fig. 6e). In addition, the CEST peak acquired with ω1 of 3.6 μT shows no distinct feature around its resonance frequency offset in the AREX spectrum (Fig. 6c), but shows a clear peak centered at around 3 – 4 ppm in the Rex_EMR spectrum (Fig. 6d). Considering some contributions from APT at 3.5 ppm (around 10% of that acquired with ω1 of 1 μT based on Fig. 1e) and the range of resonance frequencies of endogenous fast exchanging amines and hydroxyls in biological tissues (0.6 – 3 ppm) (7,13,17), the CEST peaks acquired with ω1 of 3.6 μT may center at around 3 ppm and thus could originate from glutamate amines (7,33) and/or protein lysine amine protons (34,35) which have resonance frequencies at around 3 ppm. Fig. 7 shows maps of Rex_EMR at 3 ppm with ω1 of 3.6 μT (predominated by the contrast from fast exchanging amine) and ΔRex_EMR at 3.5 ppm (predominated by the contrast from amide) from a representative rat brain.

Fig. 6.

Measured MTREMR (a), AREXEMR for amides (b), AREXEMR for fast exchanging amines (c), Rex_EMR (d), and ΔRex_EMR (e) spectra on five healthy rat brains. Error bars represent the standard deviations across subjects.

Fig. 7.

Maps of Rex_EMR at 3 ppm with ω1 of 3.6 μT (a) and ΔRex_EMR at 3.5 ppm (b) from a representative rat brain

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we show that Rex provides unique features to separate slow exchanging amides from fast exchanging and nearby intermediate exchanging amines and to correct central frequency offset in CEST imaging of fast exchanging pools. Together with EMR fitting to get the reference signal, we applied Rex in imaging animal brains. This in turn significantly improves the detection specificity of CEST imaging for more accurate quantification of molecules.

The influences of fast exchanging pools have not been comprehensively investigated in APT imaging. However, our results in Fig. 6d show that contributions from fast exchanging amines at 3.5 ppm are roughly 64 % of those from amides at 3.5 ppm with ω1 of 1 μT, suggesting that they may be a major source of errors in quantifying amide protons. These contaminations would be stronger at relatively higher ω1, which can be shown from the CEST spectra acquired with ω1 of 3.6 μT in Fig. 6a and 6d. Contaminations from intermediate exchanging amines at 2 ppm in APT imaging may not be significant at 9.4 T, but would be stronger at lower field strength. Another CEST peak at around 2.7 ppm, which cannot be easily observed in the MTREMR and AREXEMR spectra with ω1 of 1 μT in Fig. 6a and 6b, can be clearly shown in the Rex_EMR and ΔRex_EMR spectra in Fig. 6d and 6e. This peak is buried by the two nearby CEST signals from amides at 3.5 and amines at 2 ppm, and thus is overlooked. However, with the reduction of signals from amines at 2 ppm in the Rex_EMR and ΔRex_EMR spectra, it can be easily observed. This signal at 2.7 ppm is as narrow as those of amides and intermediate exchanging amines at 2 ppm and thus should be from slow or intermediate exchanging pools. According to previous phantom experiments (7,62), it may originate from phosphocreatine which has a resonance frequency at around 2.7 ppm.

Although previous studies suggest the CEST signal at 3 ppm acquired with high ω1 using MTRasym originates from glutamate, the reported central frequency of the MTRasym peak is not at 3 ppm, but at 2 ppm (7). Our MTREMR spectrum with ω1 of 3.6 μT in Fig. 6a also shows a central frequency at around 2 ppm. It has been reported that the central frequency quantified by MTR depends on multiple sequence and tissue parameters, and thus MTR provides false CEST peaks (54,56). Therefore, based only on CEST measurements, it is challenging to identify the resonance frequencies of the exchanging pools and thus the molecular origin of the CEST signals. The AREXEMR spectrum acquired with ω1 of 3.6 μT in Fig. 6c does not show any distinct feature, and thus is not appropriate to identify the resonance frequency of exchanging pools. However, the Rex_EMR spectrum in Fig. 6d suggests that this CEST effect with ω1 of 3.6 μT measures both fast exchanging amines at around 3 ppm and some minor contributions from amides at 3.5 ppm. Hydroxyl-water exchange effects may influence the MTRasym spectra, but not the Rex spectrum because they are closer to the water line (<1 ppm) and thus can be reduced by the resonance-frequency high-pass filter of Rex. This in vivo result is also in agreement with previous Rex study on phantoms that Rex can provide distinct feathers for fast exchanging CEST signals (56). The difference between Rex using Eq. (5) for the sum of three pools and the fast exchanging amine pool in Fig. 4d suggests that this method can not remove contaminations from amide and intermediate exchanging amine for quantifying fast exchanging amine. However, this contamination is minor at high power based on our simulations. The measured Rex_EMR on rat brains is 28.3 ± 3.7 s−1 (Fig. 6d), and the simulated Rex with fs of 0.005 is 60.81 (Fig. 4d). Therefore, we can estimate that the concentration of fast exchanging amines in brain should be roughly an order of magnitude higher than the glutamate concentration. This suggests that protein lysine amines at 3 ppm may be a major contribution (34,35).

In this paper, the EMR method was used to estimate reference signal in a complex tissue model. A previous study (63) indicates that, in order to get reliable fittings of the semi-solid MT parameters, multiple RF powers are necessary. Therefore, we used Z-spectra acquired with two RF powers to fit semi-solid MT parameters in the current work. In other studies (39–41,54,63), several independent semi-solid MT model parameters including T1w/T2w were obtained by fitting CEST data to Eq. (A1). However, our fitting of simulated data indicates that T1w/T2w can not be fitted accurately and this inaccuracy leads to errors to the extrapolated signals near water frequency in our study (Sup. Table. S1 and Sup. Fig. S2). This may be due to the different sampling scheme or ω1 that used for fitting the semi-solid MT model parameters. Interestingly, we found that two different approaches, i.e. (1) fitting of four independent semi-solid MT model parameters (kmw, T2m, kmwfmT1w, Δm) with a roughly estimated T1w/T2w value, or (2) direct fitting of five parameters (kmw, T2m, kmwfmT1w, T1w/T2w, Δm) with a limited fitting boundary of T1w/T2w, lead to similar accuracy in the estimation of other CEST parameters and extrapolated MT reference signals. Sup. Table. S2–S3 and Sup. Fig. S3–S4 indicate a successful EMR fitting with four independent parameters and an input of 0.8 times and 1.2 times of T1w/T2w value, respectively. Sup. Table S4 and Sup. Fig. S5 indicate a successful EMR fitting with five independent parameters and a limited fitting boundary ranging from 0 to 1.2 times of T1w/T2w value. In normal rat brains at 9.4 T, T1w and T2w distributions are in a limited range. So we obtained T1w/T2w value of 45 from literature survey (44) and fitted four independent semi-solid MT model parameters in the animal study in this paper. In pathologies with significant variations of T1w and T2w, they can be measured and included in the fittings as constants on a voxel basis. More interestingly, we find that ΔRex is not significantly influenced by the inaccurate fitting of T1w/T2w, possibly because that the subtraction of two Rex removes the fitting errors. Previous studies (64,65) indicate that the semi-solid pool in biological tissue has super-Lorentzian absorption lineshape. However, their studies also show that MT signals with frequency offsets roughly less than 16 ppm can still be fitted well by Lorentzian lineshape. In addition, another study (49) indicates that the semi-solid MT effect near water resonance can be modeled as Lorentzian lineshape. To avoid the singularity in the super-Lorentzian fitting, we used Lorentzian lineshap for the MT fitting. Here we choose sampling points from −16.25 ppm to −8.75 ppm and 8.75 ppm to 16.25 ppm with ω1 of 3.6 μT and from −10 ppm to −6.25 ppm and 6.25 ppm to 10 ppm with ω1 of 1 μT for fitting the semi-solid MT parameters. For the sampling points with ω1 of 3.6 μT, farther offsets were set to avoid the possible contaminations from fast exchanging amines which are more significant at higher powers. Both experiments in Fig. 6d and simulations in Fig. 4d show that Rex with ω1 of 3.6 μT is higher than that with ω1 of 1 μT near 5 ppm. These unmatched curves also cause the negative ΔRex values near 5 ppm in both Fig. 6e and Fig. 4e. This may be due to that our sampling points for fitting the semi-solid MT are contaminated by fast exchanging amines. Further studies require optimization of these sampling points. In the current study, this fitting error near 5 ppm is far from amide at 3.5 ppm and fast exchanging amine at 3 ppm and thus does not have significant influence on our quantifications. Since 1 μT and 3.6 μT RF irradiation powers have been previously used in detecting CEST signals from amides (44,66) and fast exchanging amines (7), respectively, we evaluated these two powers here. Further studies are necessary to optimize the powers for better sensitivity and specificity.

For quantitative CEST data analyses, it is important to estimate reference signals accurately in order to isolate the true chemical exchange effects from other confounding effects including MT and DS. Unfortunately, there is currently no perfect method for this purpose. In the current work, the EMR approach (39–41) was used for fitting reference signals, but our analysis indicates that the EMR is still not robust. Note that the Rex method introduced here is not limited to the EMR method. Some other methods, such as LD (42,43) and Lorentzian fitting (48), may be combined with Rex as well to evaluate reference signals, although the accuracy of these methods at high powers has not been comprehensively investigated either. Further development of methods for obtaining more accurate reference signals may increase the in vivo application of Rex.

Although Rex and ΔRex can significantly increase specificity, it has several drawbacks. First, ΔRex has reduced signal to noise ratio (SNR) due to the removal of CEST signals from fast exchanging amines. Further studies may be performed to increase the acquisition efficiency. For instance, the SNR could be increased and the acquisition time could be reduced through optimizing the sampling scheme. In this paper, although dense sampling of Z-spectra was performed to show clear CEST profiles, less sampling points between −5 to 5 ppm and multiple acquisitions at 3.5 ppm could significantly reduce the total acquisition time, increase the SNR for imaging amide, and keep showing a rough CEST profile from fast exchanging amine. Second, Rex and/or ΔRex requires acquisitions with two ω1, which lengthen the total acquisition time. Third, the tangent theta is sensitive to B1 error. For example, there will be 19% error in Rex when B1 has 10% error. However, B1 mapping as well as CEST acquisitions with multiple ω1 have already been used in clinical scanners to increase the specificity of CEST imaging (67). Here, we did not measure B1 since it is relatively homogenous using animal volume coil. But in situations where B1 is relatively inhomogeneous, B1 mapping is also required. Here, our study is focused on 9.4 T and two specific ω1. The relative contribution from amides and fast exchanging amines on other fields and ω1 require further studies.

CONCLUSION

Our results show that Rex can correct the shift of CEST peaks from fast exchanging amines and ΔRex can successfully remove influences from nearby CEST signals in APT imaging. This significantly enhances the detection specificity of CEST imaging to amide and fast exchanging amine protons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Sponsor: R21EB17873, R01CA109106, R01CA184693, R01EB017767

Abbreviations used

- CEST

chemical exchange saturation transfer

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- APT

amide proton transfer

- MT

magnetization transfer

- MTR

magnetization transfer ratio

- DS

direct water saturation

- LD

Lorentzian difference

- T1w

water longitudinal relaxation time

- Rex

exchange-dependent relaxation rate

- MTRasym

MTR asymmetry analysis

- AREX

apparent exchange-dependent relaxation

- rNOE

relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement

- ksw

solute-water exchange rate

- fm

semi-solid MT pool concentration

- fs

solute concentration

- R1obs

apparent water longitudinal relaxation rate

- CW

continuous wave

- SNR

signal to noise ratio

APPENDIX

Eq. (A1) gives the two-pool MT model,

| (A1) |

where kmw is the exchange rate between semi-solid and water protons; T2w is the transverse relaxation time of water pool; T1m and T2m are the longitudinal and transverse relaxation times of the semi-solid pool, respectively; Rrfm is the RF absorption rate, which depends on the absorption lineshape, gm(2πΔω) through the relationship ,

| (A2) |

where δωm is the central resonance frequency of semi-solid pool. Four independent semi-solid MT model parameters (kmw, T2m, kmwfmT1w, δωm) were obtained by fitting CEST data to Eq. (A1), based on the nonlinear least squares fitting approach, using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. In the fitting, T1m was set to 1 s (39,40). T1w/T2w was calculated using the simulation parameters for all simulation studies and set to be 45 for all animal studies. The T1w/T2w value in animals was obtained by literature survey (44). Table A1 lists the starting points and boundaries of the fit of semi-solid MT model parameters.

Table A1.

Starting points and boundaries of MT model parameters.

| Start | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kmw (s−1) | 25 | 0 | 100 |

| T2m (μs) | 16 | 1 | 100 |

| kmwfmT1w | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| δωm (ppm) | 0 | −3 | 3 |

References

- 1.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2000;143(1):79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou JY, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(8):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haris M, Singh A, Cai KJ, et al. A technique for in vivo mapping of myocardial creatine kinase metabolism. Nature Medicine. 2014;20(2):209–214. doi: 10.1038/nm.3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haris M, Nanga RPR, Singh A, et al. Exchange rates of creatine kinase metabolites: feasibility of imaging creatine by chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2012;25(11):1305–1309. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai KJ, Singh A, Poptani H, et al. CEST signal at 2ppm (CEST@2ppm) from Z-spectral fitting correlates with creatine distribution in brain tumor. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai KJ, Tain RW, Zhou XJ, et al. Creatine CEST MRI for Differentiating Gliomas with Different Degrees of Aggressiveness. Mol Imaging Biol. 2016;19(2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s11307-016-0995-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai KJ, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nature Medicine. 2012;18(2):302–306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haris M, Nath K, Cai KJ, et al. Imaging of glutamate neurotransmitter alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2013;26(4):386–391. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crescenzi R, DeBrosse C, Nanga RPR, et al. In vivo measurement of glutamate loss is associated with synapse loss in a mouse model of tauopathy. Neuroimage. 2014;101:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepin J, Francelle L, Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, et al. In vivo imaging of brain glutamate defects in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroimage. 2016;139:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis KA, Nanga RPR, Das S, et al. Glutamate imaging (GluCEST) lateralizes epileptic foci in nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy. Science Translational Medicine. 2015;7(309) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagga P, Crescenzi R, Krishnamoorthy G, et al. Mapping the alterations in glutamate with GIuCEST MRI in a mouse model of dopamine deficiency. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2016;139(3):432–439. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan KWY, McMahon MT, Kato Y, et al. Natural D-glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;68(6):1764–1773. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Chan KW, Knutsson L, et al. Dynamic glucose enhanced (DGE) MRI for combined imaging of blood-brain barrier break down and increased blood volume in brain cancer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2015;74(6):1556–1563. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu X, Yadav NN, Knutsson L, et al. Dynamic Glucose-Enhanced (DGE) MRI: Translation to Human Scanning and First Results in Glioma Patients. Tomography. 2015;1(2):105–114. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2015.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Weygand J, Hwang KP, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Glucose Uptake and Metabolism in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:30618. doi: 10.1038/srep30618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haris M, Cai KJ, Singh A, Hariharan H, Reddy R. In vivo mapping of brain myo-inositol. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2079–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Zijl PCM, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MR1 detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(7):2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeBrosse C, Nanga RPR, Bagga P, et al. Lactate Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (LATEST) Imaging in vivo A Biomarker for LDH Activity. Scientific Reports. 2016:6. doi: 10.1038/srep19517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin T, Wang P, Zong XP, Kim SG. MR imaging of the amide-proton transfer effect and the pH-insensitive nuclear overhauser effect at 9. 4 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(3):760–770. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun PZ, Cheung JS, Wang EF, Lo EH. Association between pH-weighted endogenous amide proton chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI and tissue lactic acidosis during acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2011;31(8):1743–1750. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salhotra A, Lal B, Laterra J, et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of 9L gliosarcoma and human glioblastoma xenografts. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2008;21(5):489–497. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PCM, et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56(3):585–592. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia GA, Abaza R, Williams JD, et al. Amide Proton Transfer MR Imaging of Prostate Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2011;33(3):647–654. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou JY, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PCM. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;50(6):1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou JY, Tryggestad E, Wen ZB, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(1):130–U308. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun PZ, Wang EF, Cheung JS. Imaging acute ischemic tissue acidosis with pH-sensitive endogenous amide proton transfer (APT) MRI-Correction of tissue relaxation and concomitant RF irradiation effects toward mapping quantitative cerebral tissue pH. Neuroimage. 2012;60(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun PZ, Zhou JY, Sun WY, Huang J, van Zijl PCM. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun PZ, Benner T, Copen WA, Sorensen AG. Early Experience of Translating pH-Weighted MRI to Image Human Subjects at 3 Tesla. Stroke. 2010;41(10):S147–S151. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Zu ZL, Zaiss M, et al. Imaging of amide proton transfer and nuclear Overhauser enhancement in ischemic stroke with corrections for competing effects. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(2):200–209. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dula AN, Asche EM, Landman BA, et al. Development of Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer at 7T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;66(3):831–838. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wermter FC, Bock C, Dreher W. Investigating GluCEST and its specificity for pH mapping at low temperatures. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(11):1507–1517. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zong XP, Wang P, Kim SG, Jin T. Sensitivity and Source of Amine-Proton Exchange and Amide-Proton Transfer Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cerebral Ischemia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(1):118–132. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin T, Kim SG. High field MR imaging of proteins and peptides based on the amine-water proton exchange effect. ISMRM. 2012:2339. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roalf D, Nanga R, Rupert P, et al. Glutamate Imaging (Glucest) Reveals Lower Brain Glucest Contrast in Patients on the Psychosis Spectrum. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2017;43:S49–S49. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou JY, van Zijl PCM. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 2006;48(2–3):109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zu ZL, Xu JZ, Li H, et al. Imaging Amide Proton Transfer and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Using Chemical Exchange Rotation Transfer (CERT) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;72(2):471–476. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Lee DH, Hong XH, Zhou JY. Quantitative Assessment of Amide Proton Transfer (APT) and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (NOE) Imaging with Extrapolated Semi-Solid Magnetization Transfer Reference (EMR) Signals: Application to a Rat Glioma Model at 4. 7 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(1):137–149. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Jiang SS, Lee DH, Zhou JY. Quantitative Assessment of Amide Proton Transfer (APT) and Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (NOE) Imaging with Extrapolated Semisolid Magnetization Transfer Reference (EMR) Signals: II. Comparison of Three EMR Models and Application to Human Brain Glioma at 3 Tesla Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(4):1630–1639. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Burton TM, et al. Improving the Detection Sensitivity of pH-Weighted Amide Proton Transfer MRI in Acute Stroke Patients Using Extrapolated Semisolid Magnetization Transfer Reference Signals. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones CK, Polders D, Hua J, et al. In vivo three-dimensional whole-brain pulsed steady-state chemical exchange saturation transfer at 7 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;67(6):1579–1589. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones CK, Huang A, Xu JD, et al. Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in the human brain at 7 T. Neuroimage. 2013;77:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu JZ, Zaiss M, Zu ZL, et al. On the origins of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast in tumors at 9. 4 T. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2014;27(4):406–416. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Exchange-dependent relaxation in the rotating frame for slow and intermediate exchange - modeling off-resonant spin-lock and chemical exchange saturation transfer. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2013;26(5):507–518. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zaiss M, Xu J, Goerke S, et al. Inverse Z-spectrum analysis for spillover, MT-, and T1-corrected steady-state pulsed CEST-MRI-application to pH-weighted MRI of acute stroke. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2014;27(3):240–252. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaiss M, Zu ZL, Xu JZ, et al. A combined analytical solution for chemical exchange saturation transfer and semi-solid magnetization transfer. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(2):217–230. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang XY, Wang F, Li H, et al. Accuracy in the quantification of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement (rNOE) saturation transfer effects. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaiss M, Schmitt B, Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2011;211(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desmond KL, Moosvi F, Stanisz GJ. Mapping of Amide, Amine, and Aliphatic Peaks in the CEST Spectra of Murine Xenografts at 7 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;71(5):1841–1853. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang F, Qi HX, Zu ZL, et al. Multiparametric MRI reveals dynamic changes in molecular signatures of injured spinal cord in monkeys. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25488. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang XY, Wang F, Afzal A, et al. A new NOE-mediated MT signal at around-1. 6 ppm for detecting ischemic stroke in rat brain. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2016;34(8):1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang XY, Wang F, Jin T, et al. MR imaging of a novel NOE-mediated magnetization transfer with water in rat brain at 9.4 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang XY, Wang F, Li H, et al. CEST imaging of fast exchanging amine pools with corrections for competing effects at 9.4 T. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trott O, AGP R1(rho) Relaxation outsie of the Fast-Exchange Limit. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2002;154:157–160. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin T, Autio J, Obata T, Kim SG. Spin-Locking Versus Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer MRI for Investigating Chemical Exchange Process Between Water and Labile Metabolite Protons. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;65(5):1448–1460. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and MR Z-spectroscopy in vivo: a review of theoretical approaches and methods. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2013;58(22):R221–R269. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/22/R221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H, Zu ZL, Zaiss M, et al. Imaging of amide proton transfer and nuclear Overhauser enhancement in ischemic stroke with corrections for competing effects. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(2):200–209. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang XY, Li H, Xu JZ, et al. A New MT Signal at −1.6 ppm Via NOE-Mediated Saturation Transfer. ISMRM conference; Toronto, CA. 2015; p. p0999. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging via selective inversion recovery with short repetition times. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(2):437–441. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu JZ, Li K, Zu ZL, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of rodent glioma using selective inversion recovery. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2014;27(3):253–260. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang XY, Xie JP, Wang F, et al. Assignment of the Molecular Origins of CEST signals at 2 ppm in Rat Brain. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henkelman RM, Huang XM, Xiang QS, et al. Quantitative Interpretation of Magnetization-Transfer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1993;29(6):759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrison C, Stanisz G, Henkelman RM. Modeling Magnetization-Transfer for Biological-Like Systems Using a Semisolid Pool with a Super-Lorentzian Lineshape and Dipolar Reservoir. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series B. 1995;108(2):103–113. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morrison C, Henkelman RM. A Model for Magnetization-Transfer in Tissues. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;33(4):475–482. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, Li K, Zhang XY, et al. R-1 correction in amide proton transfer imaging: indication of the influence of transcytolemmal water exchange on CEST measurements. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(12):1655–1662. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Windschuh J, Zaiss M, Meissner JE, et al. Correction of B1-inhomogeneities for relaxation-compensated CEST imaging at 7T. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2015;28(5):529–537. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, et al. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58(4):786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.